1. Introduction

The financial position and well-being of individuals depend on their actions. Even though these actions can be affected by outside factors, such as economic policies implemented by private sectors or governments, individuals eventually make financial decisions. Further, there is a growing diversification in financial services and products, which increases the complications for individuals in making investment decisions [

1]. In effect, these diversified services and products involve many choices and tools for individual investors to decide where and how to invest. In such financial circumstances, a lack of investment awareness could substantially affect an individual’s financial outcomes [

2].

Nowadays, the concept of investment awareness has received great importance as a financial concern [

3]. Hastings and Mitchell [

4] revealed that constant growth in the level of investment awareness had been witnessed globally for different age groups. Financial and investment awareness are two vital factors for the sound improvement of the financial market. Communities categorized with a high degree of financial awareness are more inclined to have individuals with strong skills in making sound investment decisions [

5]. Investors with deficient appropriate financial awareness may make unreasonable financial decisions [

6]. Further, the decisions of investors are considerably impacted by their behavior and commonly, individual investors display illogical and ineffective behavior in the market [

7].

The existence of poor financial awareness in Saudi Arabia as reported by Alshebami and Aldhyani [

8,

9], emphasizes the necessity for recognizing the crucial elements influencing investment awareness. Saving signifies an essential foundation for an individual’s investments that will lead to the growth and development of the country’s economy [

10]. Agarwalla et al. [

2] advocated that the participation of families in businesses leads to their children being more aware of the fundamentals of personal finances. Indeed, children and adults obtain financial abilities inside the family via different socialization practices such as noticing the financial behavior of their parents. A fundamental emotion, a lack of self-control, is the individual thinking concerning the accomplishment of one’s investment decisions [

11]. To this end, understanding the link between the factors, i.e., financial literacy, saving behavior, family financial socialization, a lack of self-control, and an individual’s investment awareness, is increasingly recognized as a critical financial issue.

Social influence, i.e., family, can form the principles and behaviors of an individual and thus could influence the individual’s decisions [

12]. Saving behavior can be one of the behaviors shaped by family socialization. Parents are important in guiding and instructing their children toward being financially literate [

13], that is, families represent a vital source of inspiration and education for their children about financial knowledge and behaviors such as spending and saving. For children to live well without bad financial problems, their families must educate them about financial matters and investments [

14]. Thus, examining the moderating role of family financial socialization in the association between financial literacy, saving behavior, and investment awareness is desired. Further, when investigating the link between financial literacy, saving behavior, and investment awareness, it is imperative to consider the impact of a lack of self-control on these links. It has been reported that an individual’s self-control can moderate the connection between financial literacy and saving behavior [

15]. A lack of self-control can affect the individual’s capability to monitor his/her requirements, thoughts, and actions to accomplish precise goals, i.e., saving, spending, investing, and a suitable retirement plan [

16]. Similarly, preceding work by Romal and Kaplan [

17] has also linked self-control to savings, financial management, and credit problems. It was reported by [

8] that exercising a substantial degree of self-control is needed to increase the numerous benefits of financial literacy. To this end, examining the moderating role of a lack of self-control on the relationships between financial literacy, saving behavior, and investment awareness is important.

Financial knowledge and investment awareness are receiving great interest in Saudi Arabia. For example, the Ministry of Education in Saudi Arabia is about to integrate a financial literacy course into the curriculum of the secondary stage for the current academic year 2022–2023. The General Authority for Statistics in Saudi Arabia [

18] revealed that young Saudi people aged 15 to 34 years represent 36.7% of the whole population. Young individuals lack financial awareness regarding financial planning, services, and products [

19]. Regardless of the critical modifications and reforms that happened to the Saudi economy, a low level of financial awareness still exists [

20]. It is evident from Sedais and Al Shahab [

21] that the degree of financial awareness among Saudi youth (below 37 years) is low. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Saudi young individuals’ financial literacy represents only 9.6 out of 21, signifying a weak degree of financial literacy compared to other countries [

22]. The OECD also mentioned that this degree is the lowest among the G20 countries. Alyahya [

23] pointed out that most university students in Saudi Arabia are financially illiterate. Furthermore, the Saudi Vision 2030 is considering the importance of the financial sector as it works to increase the awareness and culture of investment in the Saudi market via the Capital Market Authority (CMA) and other bodies. The Saudi Vision 2030 also aims to increase the level of saving among Saudi families to 10%. To conclude, certain awareness and capabilities are required for young individuals to make sound investment decisions. Thus, prior discussions draw attention to the existence of a gap in the investment awareness level in Saudi Arabia, which our study aims to investigate.

This study proposes to contribute to and progress the existing literature in some ways. First, it enlarges and deepens the current literature on the link between investors’ awareness and financial literacy, behaviors (saving, self-control), and family financial socialization in an emergent country, Saudi Arabia. This link has been mostly overlooked, especially in Saudi Arabia and other developing countries [

24]. Second, this study is unique as it examines the impact of both cognitive factors, i.e., financial literacy, and non-cognitive variables, such as a lack of self-control and saving behavior, on investment awareness. The prior works focused mainly on exploring cognitive factors [

25,

26]. Third, so far, there are no documented works relating to the moderating impact of both family financial socialization and a lack of self-control on the relationship between financial literacy, saving behavior, and investment awareness. Consequently, this study is pioneering in providing a distinctive perception of such moderating impacts and filling the gaps in the existing literature on a developing country, Saudi Arabia. Finally, this study has important implications for policymakers, regulators, universities, families, and individuals by considering financial and investment awareness at an early age.

The remaining parts of our study are structured as follows. The

Section 2 discusses the related literature and hypotheses building. The

Section 3 discusses the study’s methodology involving the procedures and measurements. The

Section 4 shows the data analysis and results. The discussion is presented in

Section 5. Finally, in conclusion, the implications in addition to the limitations and guidelines for future works are presented in

Section 6.

5. Discussion

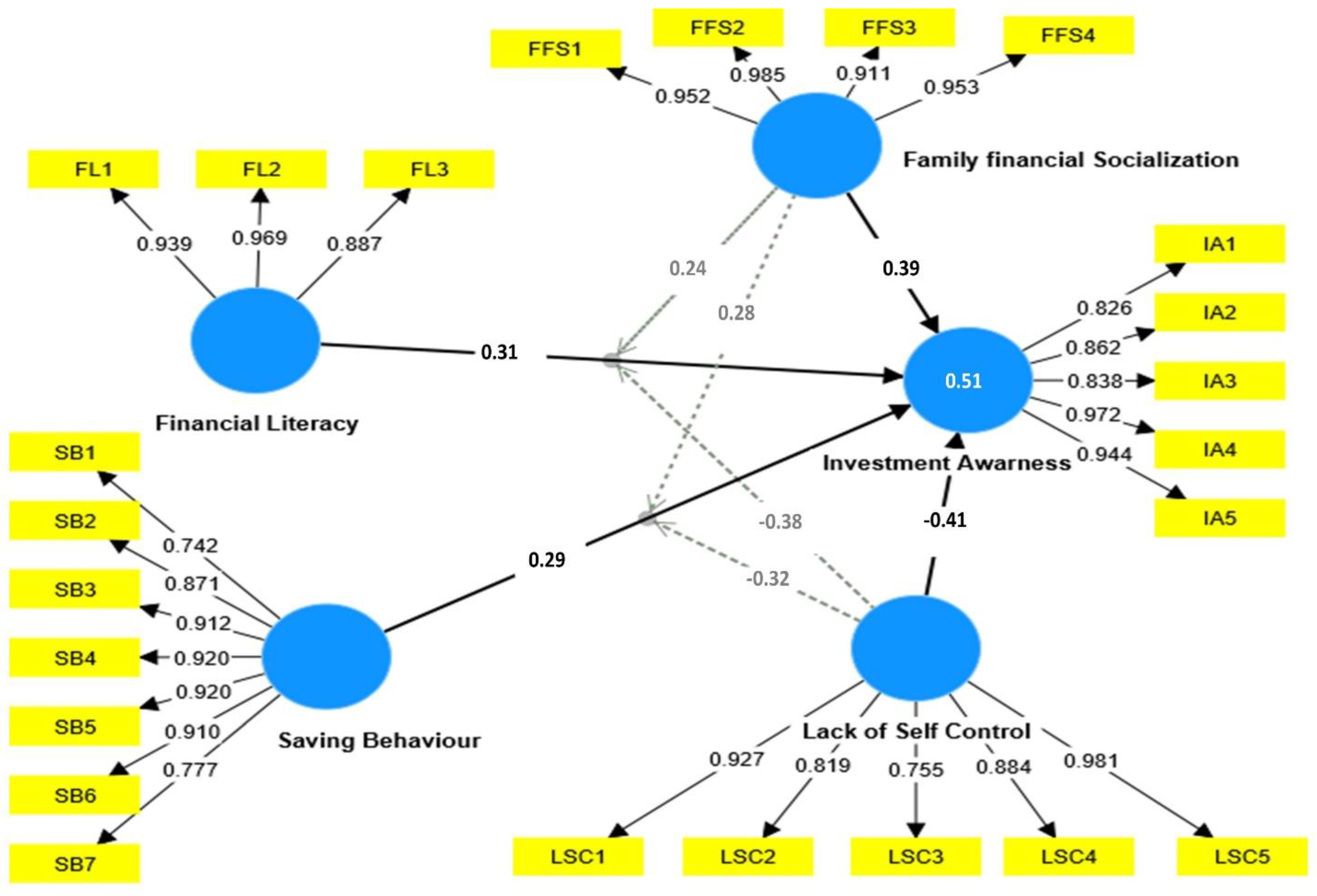

We conducted this study in Saudi Arabia, a state experiencing interest in developing its economy. In addition, young individuals represent the mainstream of the population. In line with Vision 2030, the Saudi government is enhancing its financial sector, financial awareness, investment culture, and savings rates. Therefore, Saudi students are expected to experience a considerable enhancement relating to financial and investment awareness and saving to support their well-being. Thus, the study provides noteworthy insights into the body of knowledge and practical implications by examining the direct impact of financial literacy, saving behavior, family financial socialization, and a lack of self-control on investment awareness. Further, it examines the moderating impact of family financial socialization and a lack of self-control on the links between financial literacy, saving behavior, and investment awareness.

The results of this study indicate that financial literacy is positively and significantly related to investment awareness, thus confirming our first hypothesis (H1). The findings are in line with the argument that financial literacy is a key factor in managing and dealing with money, resulting in higher financial well-being and more efficient investment decisions. A certain degree of financial knowledge is needed for better investment awareness. The results are in line with those of Azhar et al. [

26] and Azizah et al. [

31], who showed that investment awareness is positively and significantly influenced by financial literacy; Aren and Zengin [

37], who showed that financial literacy is related to preferences in investment; and Lusardi and Mitchell [

43], who showed that financial literacy enables investors to attain greater returns. In the Saudi context, our results support Saber [

3], who reported that Saudi individuals’ financial awareness has an impact on their investment choices. Concerning saving behavior, the results provide support for the hypothesis (H2) that saving behavior is positively related to students’ investment awareness. The results show that Saudi students tend to save more money. This good saving behavior will allow students to make investments in the future and solve financial problems. Based on this, the theory of social cognition is supported. Our students deal with savings as a financial source that can be reinvested in the future [

72]. Likewise, Mugo [

83] exposed that to conduct investment decisions, saving practices are needed.

Regarding family financial socialization, our theoretical hypothesis (H4) was found to be significantly supported in that the family positively impacts a student’s investment awareness. These results support the theory of social learning, which posits that the financial actions of young adults are influenced by their social surroundings including their families. Our results are also in accordance with prior studies, for example, Mpaata et al. [

15], who found that social surroundings can impact financial awareness, and Ariffin et al. [

41], who revealed that family socialization changed children’s situations from financial illiteracy into great literacy, that is, individuals are better at investing their money when their financial awareness is enhanced by their families [

15]. For a lack of self-control, our results indicate that when students are characterized by problems with self-control, this negatively impacts their investment awareness and decisions. Hence, our hypothesis (H4) is strongly supported. Liu et al. [

84] mentioned that mental accounting is a self-control tool that avoids unnecessary consumption. Hence, when individuals lack this tool, they spend more and then no more money can be saved for investments. Our results support those of Chia et al. [

85] and Esenvalde [

86], which showed that students with a lack of self-control are found to be related to more spending and less control concerning their desires. In contrast, our results are inconsistent with Mpaata et al. [

15] and Griesdorn et al. [

87] in that individuals with robust self-control have the needed skills to succeed in their financial matters.

For the moderating impact of family financial socialization on the association between financial literacy and investment awareness, our results show that family financial socialization can positively and significantly moderate this association. Thus, our hypothesis (H5) is confirmed. The reported moderating impact is in agreement with social exchange theory. This finding is in line with [

14], in that families have a better tendency to favorably influence their children’s financial awareness and attitudes. Further, Hellström et al. [

64] advocated that financial literacy and the decisions of individuals are affected by the trusted information they obtain from social relationships. In the Saudi context, Saudi students’ financial awareness is influenced by their parents [

8], which supports our results.

Regarding the other moderating impact of family financial socialization on the connection between saving behavior and investment awareness, we found that family financial socialization can strongly and positively enhance this connection. Thus, our hypothesis (H6) is accepted. Based on these results, we claim that the socialization theory is supported. The results are in accordance with prior works, for instance, Kaur and Vohra [

72], who showed that a social family variable influences investors’ investment behavior. Similar findings were found in a study on students in Bangladesh by Khatun [

71], which showed that parental socialization and saving behavior are positively related.

Finally, in terms of the moderating influence of a lack of self-control on the financial literacy–investment awareness relationship, the results signify that a lack of self-control negatively and significantly impacts this relationship. Hence, hypothesis (H7) is supported, that is, a student’s investments and financial activities are negatively affected if they are associated with a lack of self-control. In the Saudi context, our results are in line with those of [

8], which showed that the association between financial literacy and saving behavior was negatively moderated by self-control. In the same way, a lack of self-control was reported to negatively and significantly moderate the association between saving behavior and investment awareness. These results are in line with those of prior works, for example, Ameriks et al. [

76], who advocated that more spending and less wealth are related to a lack of self-control; Gathergood [

77], who stated that quick access to financial products is related to customers with a lack of self-control, and finally, Ameriks et al. [

76], who mentioned that a mature individual is associated with fewer problems with self-control than a young adult.

6. Implications and Conclusions

This study was motivated by witnessing a dearth of studies on the factors affecting financial and investment awareness, in addition to the occurrence of deprived financial awareness, specifically in Saudi Arabia. The absence or lack of financial awareness can lead young individuals to select inappropriate financial products and services and save less than they should. An awareness of finance and investment issues forms accountable attitudes and behaviors concerning managing financial matters, leading to a successful young adult life. Thus, our study proposed to examine this important issue and aimed to investigate, in the Saudi context, financial literacy, saving behavior, family financial socialization, and a lack of self-control as the determinants of investment awareness among university students (young generation). The reported results indicate that all the determinants were found to be strongly related to investment awareness with a positive relationship in the case of financial literacy, saving behavior, and family financial socialization and a negative relationship in relation to a lack of self-control.

Further, our study provided unique insights by examining the moderating role of both family financial socialization and a lack of self-control in the relationships between financial literacy and investment awareness and saving behavior and investment awareness. The results were as expected: family financial socialization has a significant and positive impact on these relationships. In contrast, a lack of self-control negatively and significantly influences these relationships.

This study builds on the prevailing studies by providing distinctive evidence of the determinants of investment awareness. It is one of the limited works available for the Saudi Arabian context. It fills existing gaps in the literature since there is insufficient work on investment awareness in emerging countries, principally Saudi Arabia. The results provide robust evidence of the significant impact of financial literacy, saving behavior, family financial socialization, and a lack of self-control on investment awareness levels. The further theoretical contribution is that the results support the social learning theory. Moreover, this study adds to the body of knowledge by considering the moderating role of both family financial socialization and a lack of self-control in the study’s theoretical framework.

In terms of the practical implications, first, the results are important for policymakers as they discuss the importance of the factors that can enhance the country’s economic growth such as increasing financial and investment awareness. Further, the low level of investment awareness among the young generation will result in the appropriate involvement of policymakers through rules, initiatives, and recommendations that can enhance this level among the adults who represent the highest percentage of the population in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, the findings will inform regulators of the effectiveness of the Saudi Vision 2030 programs that aim to enhance investment culture and saving. Concerning educational institutions (schools and universities), training programs, workshops, and courses in financial and investment awareness are needed to improve the financial knowledge of students. Finally, parents and families are advised to discuss and educate their children on financial concerns and good behaviors regarding saving and investing.