Abstract

A stochastic nutrient–phytoplankton–zooplankton model with instantaneous nutrient recycling is proposed and analyzed in this paper. When the nutrient uptake function and the grazing function are linear and the ingested phytoplankton is completely absorbed by the zooplankton, we establish two stochastic thresholds and , which completely determine the persistence and extinction of the plankton. That is, if , both the phytoplankton and the zooplankton eventually are eliminated; if and , the phytoplankton is persistent in mean but the zooplankton is extinct; while for , the entire system is persistent in mean. Furthermore, sufficient criteria for the existence of ergodic stationary distribution of the model are obtained and the persistent levels of the plankton are estimated. Numeric simulations are carried out to illustrate the theoretical results and to conclude our study. Our results suggest that environmental noise may cause the local bloom of phytoplankton, which surprisingly can be used to explain the formation of algal blooms to some extent. Moreover, we find that the nonlinear nutrient uptake function and grazing function may take credit for the periodic succession of blooms regardless of whether they are in the absence or presence of the environmental noises.

Keywords:

stochastic nutrient–plankton model; persistent level; nutrient recycling; threshold dynamics; stationary distribution MSC:

37H30; 60E05

1. Introduction

Trophic interactions in marine ecosystems, which describe the relationship between nutrients and plankton, may impact the marine ecosystems by several ways, such as changing the spatiotemporal distribution of marine lives, altering the chemistry of their environment and shaping the ecosystem diversity [1,2,3]. A well-known example is harmful algal blooms, which are caused by the explosive proliferation of certain algae under specific environmental conditions. Therefore, trophic interactions play an important role in marine ecosystems, yet the empirical study on this is limited, largely because of the complexity of these interactions and of the difficulty and high cost in measuring planktonic biomass [4,5]. Since the pioneering work by Riley et al. [6], mathematical models have proven to be effective and powerful tools for studying the interaction between nutrient and plankton [7,8,9,10,11]. For example, Wroblewski et al. [12] established a food chain model of two trophic levels to investigate the plankton densities in different ocean layer; Edwards and Brindley [4] developed and investigated a simple plankton population model, illustrating the interaction of nutrient, phytoplankton and zooplankton in the oceanic mixed layer; Zhang and Wang [13] constructed a nutrient–phytoplankton–zooplankton model in an aquatic environment and studied its global dynamics.

It has shown that mathematical modeling provides a useful tool and a cheaper way to gain deep insights into the physical and biological interactions. Now, we consider a open system, which has three interacting components consisting of phytoplankton , herbivorous zooplankton and dissolved limiting nutrient . Further suppose that the plankton are modeled by their nitrogen or phosphorous, and the nutrient is primarily responsible for limiting phytoplankton reproduction. Then a plankton–nutrient interaction model is given by the following equations

where function describes the nutrient uptake rate of the phytoplankton; represents the response function describing herbivore grazing. All parameters are assumed to be non-negative and have the biological meaning listed in Table 1. Clearly, we have and and , under which Ruan [14,15] established sufficient conditions for the stability of non-negative equilibria and the persistence; the author also showed that the coexistence of zooplankton and phytoplankton may arise when incorporating a periodic washout rate into the system. Taking as the linear forms and supposing that phytoplankton removed through zooplankton predation is all assimilated by zooplankton; that is, and , model (1) becomes

which was studied by Refs. [16,17], where authors analyzed the stability of the feasible equilibria and pointed out that the dynamics of (2) is primarily dominated by

Table 1.

Biological explanation of parameters in model (1).

More precisely, the threshold controls the persistence of the phytoplankton; the threshold governs the existence of the positive interior equilibrium.

Models (1) and (2) were formulated based on the assumption that the biological parameters are all constants. Campillo et al. [18], however, pointed out that the impact of changing environment cannot be ignored when the homogeneity condition is not met. Until now, some stochastic models describing the interaction between fluctuating environment and population have been proposed by researchers [19,20,21]. Particularly, by analyzing a stochastic phytoplankton–zooplankton system, Sarkar and Chattopadhayay [22] found that noise intensity plays a key role in the termination of planktonic blooms. Imhof and Walcher [23] constructed a stochastic single substrate chemostat model and showed that the environmental noise may cause the extinction of microorganisms. Xu and Yuan [24] also proposed a stochastic chemostat model, but with competition and for multiple species. Zhao et al. [25] concluded that allelopathy can reduce the peak of harmful algal blooms.

The goal of the paper is to formulate a stochastic nutrient–phytoplankton–zooplankton model for understanding the effects of environmental fluctuations on the dynamics of plankton. Although there have been some results on stochastic plankton models, for example, stochastic nutrient–phytoplankton models [21,23,24] and stochastic phytoplankton–zooplankton models [20,22,26,27], these papers are mainly concerned with stochastic models with two trophic levels while the present paper focuses on three trophic levels. In general, it is difficult to obtain the dynamic properties of high-dimensional stochastic models because there is no unified method to construct Lyapunov functions. So, the innovation of our paper is obvious. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we formulate the model and present our main results, including the survival analysis and the existence of ergodic stationary distribution. In Section 3, after giving some preliminaries and technical lemmas, we provide the strict mathematical proofs of the main results. Some numerical simulations are carried out to verify the theoretical results and further illustrate the effects of noise in Section 4. Finally, we conclude our study with a summary in Section 5.

2. Model Formulation and Main Results

2.1. Formulation of the Stochastic Model

In this section, we develop the stochastic version of model (1) using the approach due to Imhof and Walcher [23,24]. To this end, for a fixed time increment , we define process with initial value . Let be a sequence of normally distributed random variables satisfying

for and where reflects the densities of stochastic effects. The variables and , are supposed to capture the effects of random influences on the nutrient concentration and plankton concentration during time interval , respectively. We also further grows within that time interval according to model (1) subject to the random effect as in Refs. [28,29], resulting the discrete model

Then, according to Theorem 7.1 and Lemma 8.2 in [30], we can conclude that as ,

Here, is the solution of the following system of stochastic differential equations

with initial value and the standard independent Brownian motion is defined on a complete probability space , provided its unique solution exists. The well-posedness of stochastic model (3) is discussed in Lemma 2, which implies that the above approach to introduce stochasticity into deterministic model (1) is mathematically and biologically reasonable. Due to the existence of stochastic effects, it is much more difficult to study the threshold dynamics of general stochastic food chains model (3). Then we first consider a special case that the nutrient uptake function and the grazing function are linear and all phytoplankton removed through zooplankton predation is assimilated by zooplankton. Then model (3) becomes

which happens to be the stochastic version of (2). A natural question is how the environmental noises effect the threshold dynamics of model (4), namely whether stochastic model (4) has a similar threshold dynamics to its deterministic counterpart (2). More precisely, in this study, we aim to explore:

For the general case, in order to explore the interaction between randomness and plankton, we numerically investigate the effects of nonlinear nutrient uptake functions and the fraction of zooplankton nutrient conversion on the asymptotic dynamics of model (3).

2.2. Main Results

For the simplicity of discussion, we define the stochastic versions of and as follows

Please notice that without the perturbation, namely , , the stochastic thresholds becomes the deterministic versions , .

We are now presenting our main results of the paper, but the proofs will be given in Section 3.

Theorem 1.

Assume is the solution of the stochastic model (4) with initial value . Then, the following conclusions hold.

- (a)

- If , then both phytoplankton and zooplankton go extinct, namelyalmost surely (a.s.). Moreover,

- (b)

- If and , then the population of phytoplankton is stable in mean and the zooplankton goes extinct. Mathematically, it means a.s. and

- (c)

- If , then both phytoplankton and zooplankton are persistent in mean, namelyalmost surely for some constant .

Theorem 1 gives the sufficient and necessary criteria for the persistence of plankton, but it does not provide information about the level of persistence of the plankton. The following theorem will address this.

Theorem 2.

Remark 1.

Similar to the proof of Theorem 2 in Section 3.2, we can further obtain that under , model (4) has a unique ergodic plankton-free stationary distribution satisfying

In addition, under and , model (4) also has a unique ergodic zooplankton-free stationary distribution satisfying

Remark 2.

When the parameters in model (4) are replaced by some quantities that may change over time according to a discrete Markov chain or periodically, model (4) becomes a switching system or a non-autonomous system, which is also studied in our other related papers. It is worth noting that the research given in present paper is more thorough. Especially, the dynamics of model (4) is completely determined by the two stochastic thresholds, and . In addition, the persistent levels of plankton are also estimated explicitly.

3. Proofs of Our Main Results

3.1. Preliminaries

In this section, we provide some auxiliary definitions and results concerning the asymptotic properties, which are needed when proving the main results. To be biological meaningful, we restrict our discussion on model (4) in region

over which define the Borel -algebra and a complete probability space with a filtration satisfying the usual conditions. Then, in state space , consider the Markov process described by

where is a standard 3-dimensional Brownian motion, functions and satisfy the local Lipschitz condition. Then, the diffusion matrix of is

Introduce a differential operator

It is easy to see that is uniformly elliptical in . That is, there exists such that

for any and , where the norm is defined as

Then, one has the following lemma established by Khasminskii [31].

Lemma 1

([31]). Assume there exists a bounded open set with a smooth boundary Γ, satisfying the following conditions:

- (a1)

- is uniformly elliptical in the domain and some neighborhood thereof, where .

- (a2)

- There exists a non-negative -function and a positive constant C such that , for any . Here, is the generator of X.

Then the Markov process has a unique stationary distribution , and for any integrable function with respect to the measure π we have

Furthermore, we can prove some basic properties of model (4) that are useful in discussing our main results. What we need to point out here is that for model (3), the following Lemmas 2–4 also hold.

Lemma 2.

Given initial valve , model (4) admits a unique positive solution for ; furthermore, the solution will remain in with probability one.

Proof.

The proof is similar to that of Theorem 3.1 in [32] and hence is omitted. □

Using the non-negative semimartingale convergence theorem, Theorem 3.9 in [33], it is easy to prove that the following conclusions are valid.

Lemma 3.

The solution = established in Lemma 2 satisfies

Ecologically, the extinction of prey will lead to the extinction of predators, so the following conclusion is obvious.

Lemma 4.

For model (4), if a.s., then a.s.

Lemma 5.

For any initial value , model (4) is stochastically ultimately bounded and permanent.

Proof.

Define where , and

Using the fact that we get

Note that

where

Then

which implies

Choose sufficiently large such that . By virtue of Chebyshev inequality,

It follows that

Using the fundamental inequalities , then

That is,

and

where . According to the definitions of stochastically ultimate boundedness and stochastic permanence (see [19]), the desired results can be obtained easily. This completes the proof. □

In what follows, we prove the main results, namely Theorems 1 and 2.

3.2. Proof of Theorem 1

Proof.

Next, we prove the three conclusions of Theorem 1 one by one.

Let us first prove . Substituting (15) into (13) leads to that

where Noticing that and (16), we obtain

which, together with (17), yields

That is, if . It then follows from Lemma 4 that Furthermore, according to (15), it is easy to see that

This completes the proof of .

Now we prove . From (17),

It then follows from and Lemma 4 in [34] that

Clearly, if , then That is to say, for arbitrary , there exist a set with and a constant such that

for and . When this inequality is used in (17), we obtain

This, together with Lemma 4 in [34] and the arbitrariness of , implies

So we have

Using (15) again,

That is,

This completes the proof of .

We are now to prove . From Lemma 3, the left of Equation (22) is non-positive, which implies

Thus,

Applying Lemma 3 again leads to

which implies if . In addition, the persistence in mean of phytoplankton can be obtained easily by using Lemma 4. This completes the proof of . □

3.3. Proof of Theorem 2

Due to the complexity of the proof of Theorem 2, we will split the proof into two steps.

3.3.1. Step 1: Existence of the Unique Ergodic Stationary Distribution

To complete the proof of ergodicity, we need to verify the conditions and in Lemma 1.

First, let us verify condition . That is, we need to construct a -continuous function and a bounded closed such that for . For convenience, denote , , , and choose a constant such that Then define a -function : as follows

where

and is defined as in (27). Then, it is easy to check that is continuous and

where Hence has a global minimum point in the interior of . We finally define the non-negative and -continuous function by

Note that from Itô’s formula, we have

and

where

Based on the above inequalities, we then obtain

Now we further define a bounded closed set

where and satisfies

Next, we will prove on . For the sake of convenience, we divide into where

If we show in each , then the conclusion on is true. For this reason, we discuss it in six cases.

Case 1: . Define

Then, when , we have

which and (28) implying for all .

Case 2: . If , then and

Case 3: . In this case, we first have and then

Case 4: . If , then

where

In view of (29), we can conclude that for all .

Case 5: . If , then

Again, Inequality (29) implies for all .

Case 6: . Using (29), we have

for all .

In short, we have implying that condition in Lemma 1 holds with

On the other hand, we can find such that

for all , which implies that condition in Lemma 1 also holds. Thanks to Lemma 1, model (4) has a unique stationary distribution and it is ergodic.

3.3.2. Step 2: Estimation of the Convergence Rates

In the following, we establish the convergence rates of and . According to the ergodic property established in Step 1, for any , we obtain

Moreover, Lemma 5 implies that where is a given positive constant. This, together with the dominated convergence theorem, implies

Then,

which implies

by letting . Thus, function is integrable with respect to . Then, by the ergodic property

Next, we show that by proof of contradiction. In fact, if , there exists a such that for , which implies

This contradicts (34).

If , there exists a such that for . It thus derives

which contradicts with (34) again. Consequently, Similarly, . This, together with (13), (14), (15) and (34), yields

Obviously, (35) has a unique positive solution if , where

This completes the proof of Theorem 2.

4. Numerical Simulation

In this section, some numerical simulations are carried out to verify the obtained theoretical results and further explain the effects of noise and nonlinear uptake and grazing functions on the population persistence.

4.1. The Influence of the White Noise on the Dynamics of Model (4)

Denote the equilibrium points of the deterministic model (2) by and . Then, we can verify that

and

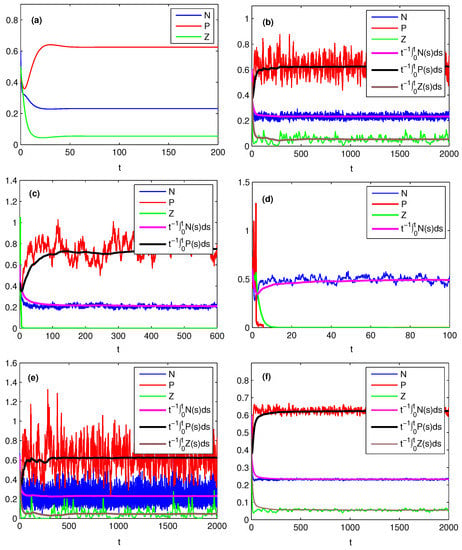

when , . That is to say, stochastic model (4) preserves the properties of the solutions of its corresponding deterministic model (2) when the intensities of noise are relatively small. Please see Figure 1, where we numerically demonstrate this observation by different parameter settings. Figure 1a shows the solution of (4) without effects of environmental noise, namely . When parameters are set such that , the positive equilibrium is asymptotically stable. When increasing noise intensities from zero, but keeping them relatively small such that , the solution is still stable, see Figure 1b,e,f. In this scenario, we can ignore the effect of noise, and use deterministic model to characterize the interaction between nutrient and plankton.

Figure 1.

Effects of noise on the dynamics of model (4) for , , , , , , , , , . (a) , then , and which is asymptotically stable; (b) , , then , i.e., the entire system is persistent; (c) , , , then and , i.e., the phytoplankton is stable in mean and the zooplankton goes extinct; (d) , , , then , i.e., both phytoplankton and zooplankton go extinct; (e) , , , then ; (f) , then .

To obtain deep insights of the effects of noise on population dynamics, we take a closer look at the definitions of from which one can see , , implying the possibility that due to the continuity of in , . Then, biologically, implies that when the phytoplankton is persistent in deterministic model (2), it may be extinct with probability one in stochastic model (4) due to the effect of environmental noise; when , we have the similar conclusion for population of zooplankton. The simulation results are reported in Figure 1a,c,d. Biologically, this means that the survival of plankton may change significantly when the stochastic perturbations are large. In this scenario, we can not ignore the effect of noise, and should use stochastic model instead of the deterministic model to describe the dynamics of plankton.

In previous studies, such as [23,34,35,36], researchers show that the environmental noise may increase extinction risk of a species. Different to that, in our present study for the nutrient–plankton food chain model, we find according to Theorem 1 that the environmental noise experienced by nutrient does not have any effect on the persistence of nutrient and plankton regardless of its intensity; however, if environmental noise experienced by phytoplankton is too large, i.e., , then both phytoplankton and zooplankton are extinct; if environmental noise experienced by phytoplankton is not too large while environmental noise experienced by zooplankton is very large, i.e., , , then phytoplankton is persistent and zooplankton will tend to extinction; If phytoplankton and zooplankton do not experience too large noise, i.e., , , then both phytoplankton and zooplankton will persist. Here

The above discussions show that the survival of phytoplankton only depends on the effect of environmental noise on itself, the survival of zooplankton depends on the effects of environmental noise on itself and phytoplankton, and nutrient is always persistent regardless of the intensity of the noise. Now let us give some numerical simulations, shown in Figure 1 for different , and to illustrate these conclusions. Comparing Figure 1b with Figure 1c, we know that with the increasing of , zooplankton goes extinct, however, nutrient and phytoplankton are still persistent. Similarly, comparing Figure 1b with Figure 1d one can see that with the increasing of , both phytoplankton and zooplankton go extinct; however, nutrient is persistent. Meanwhile, comparing Figure 1b with Figure 1e we can find easily that with the increasing of , the persistence of nutrient and plankton remains the same, namely, they are still persistent.

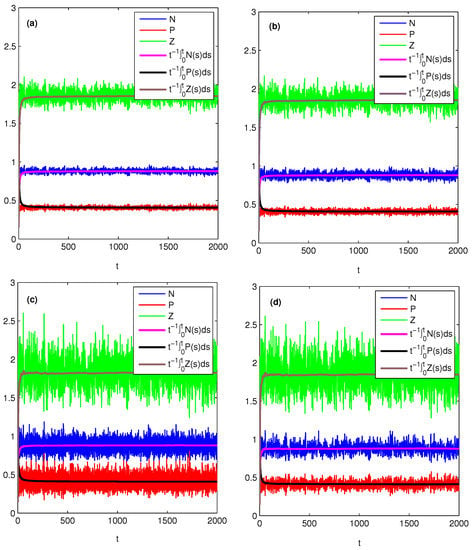

From Theorem 2, it is easy to see that the persistent level of nutrient or zooplankton depends on the effects of environmental noise on both phytoplankton and zooplankton, while the persistent level of phytoplankton only depends on the effect of environmental noise on zooplankton. Assuming and noting that the expression of in Theorem 2, phytoplankton will persist better when increasing . This is because zooplankton feeds on phytoplankton, and with the increasing of , zooplankton tends to become extinct, so phytoplankton can grow vigorously. For the effects of and on nutrient and zooplankton, we can analyze similarly. Next let us give some numerical simulations with different , and to verify these findings, see Figure 2. Comparing Figure 2a with Figure 2b, we see easily that the persistent levels of nutrient and plankton do not change with the increasing of . Comparing Figure 2a with Figure 2c, one can see that with the increasing of , the persistent level of nutrient increases, while the persistent level of zooplankton decreases. More interestingly, the persistent level of phytoplankton does not change. Comparing Figure 2a with Figure 2d we can obtain that with the increasing of , the persistent levels of nutrient and zooplankton decrease, while the persistent level of phytoplankton increases.

Figure 2.

Effects of noise on the population persistent level. Here, , , , . Then , and which is asymptotically stable. (a) , , then , , ; (b) , then , , ; (c) , then , , ; (d) , then , , .

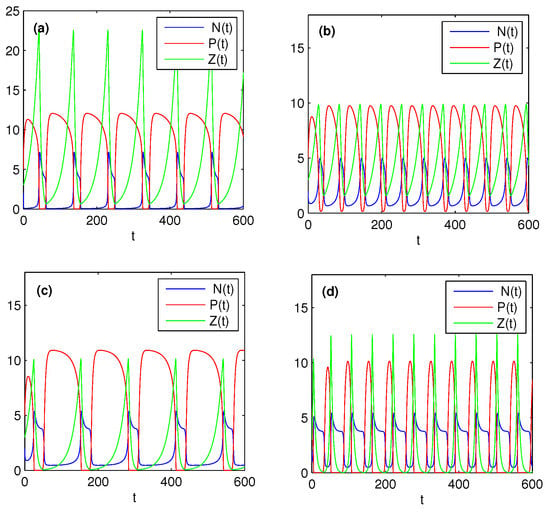

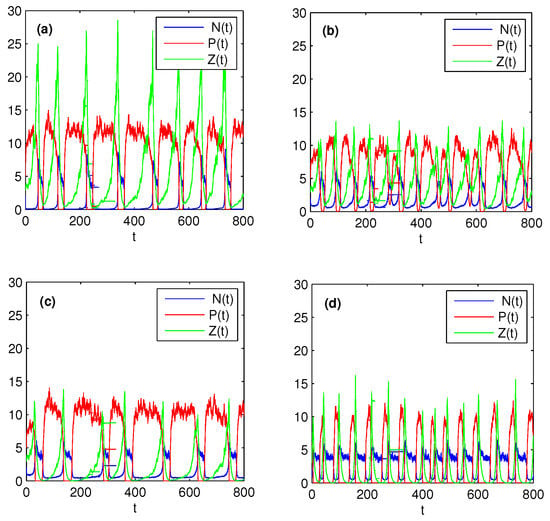

4.2. Role of Nonlinear Nutrient Uptake Rate and Functional Response for Herbivore Grazing

In this subsection, we numerically investigate how the nonlinear nutrient uptake rate and functional response for herbivore grazing affect the long-term dynamics of stochastic model (3). For certainty in numerical simulation, we assume as in [15] that

then stochastic model (3) becomes the following form:

Ruan [15] proved that under and , the corresponding deterministic system of (37) persists if and only if

where .

Now we select several parameters as in Figure 3 satisfying condition (38), which ensures system (37) without stochastic perturbations is persistent. Figure 4 shows that the effects of different k, and on the dynamics of model (37) under stochastic perturbations. From Figure 3 and Figure 4, it is not difficult to find that stochastic system (37) under small perturbations preserves the properties of the solutions of its corresponding deterministic system, which has been illustrated in Section 4.1. Comparing Figure 4a with Figure 4b, we further observed that increasing the half saturation constant k of the nutrient uptake function can significantly decrease the peak and period of the algae outbreak. These conclusions are contrary if we increase , see Figure 4b,c. Finally, comparing Figure 4c with Figure 4d, it is easy to see that increasing the fraction of zooplankton nutrient conversion may increase the frequency of algae blooms. All these numerical observations show that nutrient uptake functions and zooplankton nutrient conversion rate play an important role in the periodic oscillatory succession of bloom and greatly affect the interactions between nutrients and plankton.

Figure 3.

Effects of nonlinear uptake and grazing functions on the population persistence in deterministic environment. Here, we take , , , , , , , , , . (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) .

Figure 4.

Effects of nonlinear uptake and grazing functions on the population persistence in stochastic environment. Here, , , . (a) ; (b) , , ; (c) ; (d) . All the other parameters are the same as Figure 3.

5. Conclusions

Environmental noise is ubiquitous in nature and prominently affects population dynamics [37]. This may be especially true for plankton populations due to the unpredictability of weather, temperature and many other physical factors embedded in aquatic ecosystems (see [20,22,23]). To better understand the interactions between nutrients and food webs, in this paper, we proposed and studied a stochastic food chain model with instantaneous nutrient recycling. Under assumption that the functional response functions are linear, we observed that there are two thresholds between persistence in mean and extinction of plankton. The thresholds not only provide sufficient criteria for the existence of a unique ergodic stationary distribution, but also the explicit estimations of the mean abundance of plankton.

Comparing with the previous study, which shows that the deterministic model (2) has two thresholds and , completely determining the dynamic behaviors of the model, we also found two thresholds and for the stochastic counterpart (4). They play the similar roles to that of and , in determining the persistence and extinction of species. More precisely,

- (a)

- Neither the phytoplankton or the zooplankton can survive eventually if ;

- (b)

- The phytoplankton is persistent in mean while the zooplankton goes extinct if and ;

- (c)

- The entire system is persistent in mean if .

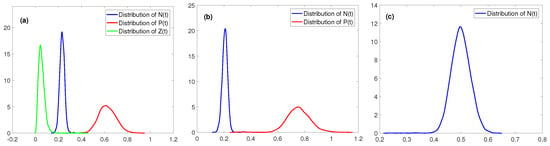

These results are illustrated in Figure 1. In addition, we have also established sufficient criteria for the existence of plankton-coexistence stationary distribution (see Figure 5a), zooplankton-free stationary distribution (see Figure 5b) and plankton-free stationary distribution (see Figure 5c). Biologically, and may be treated as the basic reproduction numbers for the phytoplankton and zooplankton in stochastic sense, respectively. In what follows, we give more relevant biological explanations of them. From the definition,

we see that the second term is due to the effect of the environmental noise. Therefore, can be interpreted as the ratio of the maximal nutrient uptake rate of phytoplankton to its loss rate under the influence of noise, which measures the ability of the nutrient environment to support a phytoplankton population. That

may be viewed as the ratio of the maximal ingestion rate of zooplankton to its loss rate under the influence of noise when the persistent level of phytoplankton biomass is stabilized at the level.

Figure 5.

The distributions of , and , where all parameters in (a–c) are the same with these in Figure 1b–d, respectively.

In short, we can draw a conclusion that noise only affects the level of nutrient but does not change its asymptotic behavior. However, for plankton, environmental noise not only can affect its biomass levels, but also their destiny of survival. This may give some insightful understanding on how environmental noise affects the dynamics of nutrient–plankton. More importantly, an interesting phenomenon that we have observed is the mean abundance of phytoplankton under small stochastic perturbations exceeds the coexisting steady-state value, but the mean abundance of zooplankton is just the opposite, see Figure 2. In fact, these results are also obtained by (10). This is an important biological finding that implies that moderate noise may cause the bloom of phytoplankton, which partly explains the formation of algal blooms. Moreover, numerical observations show that uptake functions and zooplankton nutrient conversion rate play a key role in the periodic oscillatory succession of bloom and greatly affect the interactions between nutrients and plankton; therefore, the obtained results provide a possible predictive management theoretically.

This paper is concerned with the threshold dynamics and stationary distribution of a stochastic nutrient–plankton food chain model with instantaneous nutrient recycling. The obtained results enrich the research of dynamics in nutrient–plankton model, which can help us better understand the interaction between them in a stochastic sense. In addition, some interesting questions deserve further investigation, such as whether there are still two basic reproduction numbers for the stochastic nutrient–plankton food chain model with general nutrient uptake functions? We leave these for future investigations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Y.; Formal analysis, L.C.; Methodology, X.Y.; Writing—original draft, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 12171441, 12071293), the Key Scientific Research Project of Colleges and Universities of Henan Province (No. 21A110024), the Key Science and Technology Research Project of Henan Province (No. 222102320432).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Amin, S.A.; Hmelo, L.R.; Van Tol, H.M.; Durham, B.P.; Carlson, L.T.; Heal, K.R.; Morales, R.L. Interaction and signalling between a cosmopolitan phytoplankton and associated bacteria. Nature 2015, 522, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.R.A.; Barletta, M.; Costa, M.F. Seasonal distribution and interactions between plankton andmicroplastics in a tropical estuary. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 165, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunda, W.G. Feedback interactions between trace metal nutrients and phytoplankton in the ocean. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.M.; Brindley, J. Zooplankton mortality and the dynamical behaviour of plankton population models. Bull. Math. Biol. 1999, 61, 303–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javidi, M.; Ahmad, B. Dynamic analysis of time fractional order phytoplankton-toxic phytoplankton-zooplankton system. Ecol. Model. 2015, 318, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, G.A.; Stommel, H.; Burrpus, D.F. Qualitative Ecology of the Plankton of the Western North Atlantic; Bulletin of the Bingham Oceanographic Collection; Bingham Oceanographic Laboratory: Singapore, 1949; Volume 12, 169p. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, A.; Pal, S.; Chatterjee, S. Bottom up and top down effect on toxin producing phytoplankton and its consequence on the formation of plankton bloom. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 218, 3387–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Fan, M.; Liu, R.; Zhu, H. The dynamics of temperature and light on the growth of phytoplankton. J. Theor. Biol. 2015, 385, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J. Phytoplankton-zooplankton dynamics in periodic environments taking into account eutrophication. Math. Biosci. 2013, 245, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Smith, H.L.; Kuang, Y.; Elser, J.J. Dynamics of stoichiometric bacteria-algae interactions in the epilimnion. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2007, 68, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, T.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Complete global and bifurcation analysis of a stoichiometric predator-prey model. J. Dyn. Diff. Equ. 2018, 30, 447–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wroblewski, J.S.; Sarmiento, J.L.; Flierl, G.R. An ocean basin scale model of plankton dynamics in the North Atlantic, 1. Solutions for the climatological oceanographic condition in May. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 1988, 2, 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, W. Hopf bifurcation and bistability of a nutrient-phytoplankton-zooplankton model. Appl. Math. Model. 2012, 36, 6225–6235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S. Oscillations in plankton models with nutrient recycling. J. Theor. Biol. 2001, 208, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruan, S. Persistence and coexistence in zooplankton-phytoplankton-nutrient models with instantaneous nutrient recycling. J. Math. Biol. 1993, 31, 633–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canale, R.P. An analysis of models describing predator-prey interaction. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1970, 12, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Chattopadhyay, J. Role of toxin and nutrient for the occurrence and termination of plankton bloom-results drawn from field observations and a mathematical model. Biosystems 2007, 90, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campillo, F.; Joannides, M.; Larramendy-Valverde, I. Stochastic modeling of the chemostat. Ecol. Model. 2011, 222, 2676–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mao, X. Population dynamical behavior of non-autonomous Lotka-Volterra competitive system with random perturbation. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. Ser. B 2009, 24, 523–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, R.J.; Allen, E.J. Deterministic and stochastic nutrient-phytoplankton-zooplankton models with periodic toxin producing phytoplankton. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 271, 52–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Jiang, D.; O’Regan, D. The periodic solutions of a stochastic chemostat model with periodic washout rate. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2016, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.R.; Chattopadhayay, J. Occurrence of planktonic blooms under environmental fluctuations and its possible control mechanism: Mathematical models and experimental observations. J. Theor. Biol. 2003, 224, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhof, L.; Walcher, S. Exclusion and persistence in deterministic and stochastic chemostat models. J. Differ. Equ. 2005, 217, 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Yuan, S. Competition in the chemostat: A stochastic multi-species model and its asymptotic behavior. Math. Biosci. 2016, 280, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, T. Stochastic periodic solution of a non-autonomous toxic-producing phytoplankton allelopathy model with environmental fluctuation. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2017, 44, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.R.; Chattopadhayay, J. The role of environmental stochasticity in a toxic phytoplankton-non-toxic phytoplankton-zooplankton system. Environmetrics 2003, 14, 775–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, T. Survival and ergodicity of a stochastic phytoplankton-zooplankton model with toxin-producing phytoplankton in an impulsive polluted environment. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 347, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahrouz, A.; Settati, A.; Akharif, A. Effects of stochastic perturbation on the SIS epidemic system. J. Math. Biol. 2016, 74, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Fan, M. Permanence of stochastic Lotka-Volterra systems. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2016, 27, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrett, R. Stochastic Calculus; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hasminskii, R.Z. Stochastic Stability of Differential Equations; Sijthoff and Noordhoff: Rockville, MD, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, A.; Greenhalgh, D.; Hu, L.; Mao, X.; Pan, J. A stochastic differential equation SIS epidemic model. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2011, 71, 876–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X. Stochastic Differential Equations and Applications; Horwood Publishing: Chichester, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Bai, C. Analysis of a stochastic tri-trophic food-chain model with harvesting. J. Math. Biol. 2016, 73, 597–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Kang, Y.; Banerjee, M.; Wang, W. A stochastic SIRS epidemic model with infectious force under intervention strategies. J. Differ. Equ. 2015, 259, 7463–7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, S.; Cui, J. Threshold dynamics and ergodicity of an SIRS epidemic model with Markovian switching. J. Differ. Equ. 2017, 263, 8873–8915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, R.M. Stability and Complexity in Model Ecosystems; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).