1. Introduction

Continuous and discrete-time dynamical systems can be used for modeling many applications in the surrounding world [

1,

2,

3]. Discrete dynamical systems may appear in “practical applications when a phenomenon cannot be observed continuously in time” [

4], but in certain moments of time [

5]. Additionally, they can be obtained from dynamic systems with continuous time by discretizing time, that is, if we only take certain values for time [

6] or as return maps that are return applications defined by the intersections of the system flows with certain “surfaces transversal to the flows” [

4].

From a computational point of view, the use of dynamical systems with discrete time is more efficient in modeling because it can capture complex behaviors that cannot be easily captured otherwise [

7,

8,

9]. Among the most “important topics in the qualitative theory” [

10] of continuous and discrete dynamic systems is the analysis of bifurcations (see [

11]).

One of the topics of interest in discrete dynamical systems is represented by the Chenciner bifurcation. Using the notations of the fundamental book of Kuznetsov, [

12], page 405, a discrete Chenciner bifurcation happens when

,

and

A parametric transformation

is needed in the regular case where the functions

and so on, see [

12], page 405. That transformation must be regular at the origin in order to have a non-degenerated Chenciner bifurcation.

The non-degenerate Chenciner bifurcation was firstly studied in the papers [

6,

13,

14]. More recently this bifurcation appears in many papers from different areas of research, in “biology, physics, economy, informatics” [

15] as well as multidisciplinary and applied sciences [

12,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. For example, in [

31], the Chenciner bifurcation was observed when a potential mechanism from bifurcation analyses was used for studying the occurrence of modulated oscillations in synchronous machine nonlinear dynamics, being reported for the first time in power engineering for this bifurcation. Other authors have analyzed the normal forms to provide the parameter conditions for the Chenciner bifurcation [

32] or the conditions to obtain a Chenciner bifurcation in macroeconomics [

33].

Rational expectations are the foundation of modern finance. However, in principle, the efficient market hypothesis cannot help accurately predict future prices. There is ample empirical evidence that developments in financial time series, in the form of “stylized facts”, cannot be explained by fundamentals alone, and markets appear to have specific internal dynamics. Among the so-called “stylized facts” is volatility clustering. It appears that if changes in asset prices are unpredictable, the magnitude of those changes is predictable; Thus, “large changes tend to be followed by large changes” [

19] (either increasing or decreasing), while“ small changes tend to be followed by small changes” [

19]. That is why it is found that asset price fluctuations present “episodes of high volatility” [

19] (with large price changes), which alternate irregularly with “episodes of low volatility” [

19] (with small price changes).

In economics, in a series of empirical studies, the used model is useful only for a statistical description of the data [

34]. However, these models cannot explain the clustering of volatility that is recorded in many financial time series. Typically, such models assume that volatility clustering is generated by factors external to the analyzed system.

Some structural explanations of volatility clustering are provided by “multi-agent systems” [

19], where financial markets have been approached as “complex evolutionary systems” [

19]. In such systems, two large categories of traders have been identified: fundamentalists (who state that prices are oriented toward the value of their fundamental rational expectations, generated by future dividends) and technical analysts (who, starting from the past prices, and based on some established models, try to project them in the future). Such systems show an irregular transition between low volatility situations (during which prices tend toward the fundamental price and then the market is dominated by fundamentalists) and high volatility situations (during which “prices move away from the fundamental price” [

19] and then the market is dominated by technical analysts) [

19]. In these conditions, the grouping of volatility can have endogenous explanations, that is, it could be caused and even amplified by the process of the heterogeneity of trading, but also by the interaction between agents, as well as by the phenomenon of adaptive learning.

The evolutionary model proposed by A. Gaunersdorfer, C.H. Hommes and F.O.O. Wagener presents the “coexistence of a stable state and a stable limit cycle” [

19]. When such a system is subject to dynamic noise, there is an irregular switching between fundamental equilibrium fluctuations close to rational expectations (in which “the market is dominated by fundamentalists) and large-amplitude price fluctuations” [

19] (in which the market is dominated by technical analysts). “The coexistence of a stable equilibrium state and a stable limit cycle ” [

19] is explained mathematically by means of the discrete Chenciner bifurcation. This is not caused by a particular specification of the model, but “is a generic feature for nonlinear systems with two or more parameters” [

19].

The discrete degenerated Chenciner bifurcation is produced when the above mentioned regularity of the

transformation is not fulfilled. That results in a much more difficult scenario. A first type of such a degenerated Chenciner discrete dynamical was solved in [

4]. Two other types of possible degeneration were studied in [

10,

15]. Each of those cases has a quite different method of solving. In the present article, we study another case of a possible degeneration. So, why bother with such particular cases, each having a specific kind of approach? An Edmund Hillary type of answer would be, “because they exist”, and also one may see the complexity of nature’s singularities reflected by mathematics.

In [

4], the bifurcation diagrams were discovered in a general case, where the functions

and

both have linear terms different from zero that satisfy the degeneracy condition

or

see (

1). In that case, 32 bifurcation diagrams were obtained. A parallel approach to that of [

4] is studied in [

35] by using another regular transformation of parameters, where the product

In the article [

15], the functions

and

have

, obtaining four bifurcation diagrams. Ref. [

10] studied the case when

and

or

and

, obtaining 18 different bifurcation diagrams. The stability of the fixed point

O for

that is sufficiently small and, respectively, “the existence of closed invariant curves in the” [

4] truncated normal form in all the cases was treated before [

10,

15,

35].

A possible application of the degenerated Chenciner bifurcation was presented in [

15], but one could analyze in all previous mentioned Chenciner papers what happens when degeneration occurs. For example, the volatility of the economics systems based on discrete Chenciner bifurcation may be interpreted as a variant of input data implying the degeneration of the bifurcation. One possible cause of that may be the presence of a noise, rendering a sequence of different degenerated and non-degenerated variants of the initial system in case the coefficients

have small values.

The purpose of this article is to investigate the behavior of the dynamical system when

or

has a zero linear part

or

, see (

1), and the second function has at least a term of order one different from zero. This aspect has not been analyzed before. As it is not possible to choose new coordinates

, the idea is to use only the initial parameters

. This leads to the modifications of the structure of the sets of points

and

C, thus obtaining concurrent lines at the origin, similar to the situation analyzed in other articles [

10,

15], but different from the cases studied in [

4,

35]. We want to specify how many bifurcation diagrams are obtained, many or few. The first case studied, when

, is the most important and complex of the two and requires different methods of approach (the second is when

).

The starting hypothesis in this study is that in the case of a degeneracy, a larger number of bifurcation diagrams is needed than in a non-degeneracy setting. The objective of this article is to verify the mentioned hypothesis in a degeneracy case that does not involve resonance.

The work is structured in six sections; after the Introduction (

Section 1 and

Appendix A and

Appendix B),

Section 2 presents the analysis of degenerate Chenciner bifurcation that “means the existence and stability of equilibrium points and invariant closed curves” [

4] for this form of degeneracy, known as non-transversality, i.e., the “transformation of parameters is not regular at

” [

35]. In

Section 3, it is described the existence of bifurcations curves and their dynamics in the parametric plane

in Theorem 1.

Section 4 shows the bifurcation diagrams for this type of degeneracy of Chenciner bifurcation when the smooth function

is of order two. These bifurcation diagrams are different from the bifurcation diagrams from the non-degenerate framework. In

Section 5, several numerical simulations using Matlab check the theoretical results from the previous section.

Section 6 indicates the relevant discussions and conclusions of the paper.

4. Bifurcation Diagrams

Assume

and

have nonzero coefficients in their lowest terms, that is,

and

Thus, “the three bifurcation curves are well-defined when

is sufficiently small ” [

4].

is a unique curve, while each of

and “

C is a reunion of two curves” [

15].

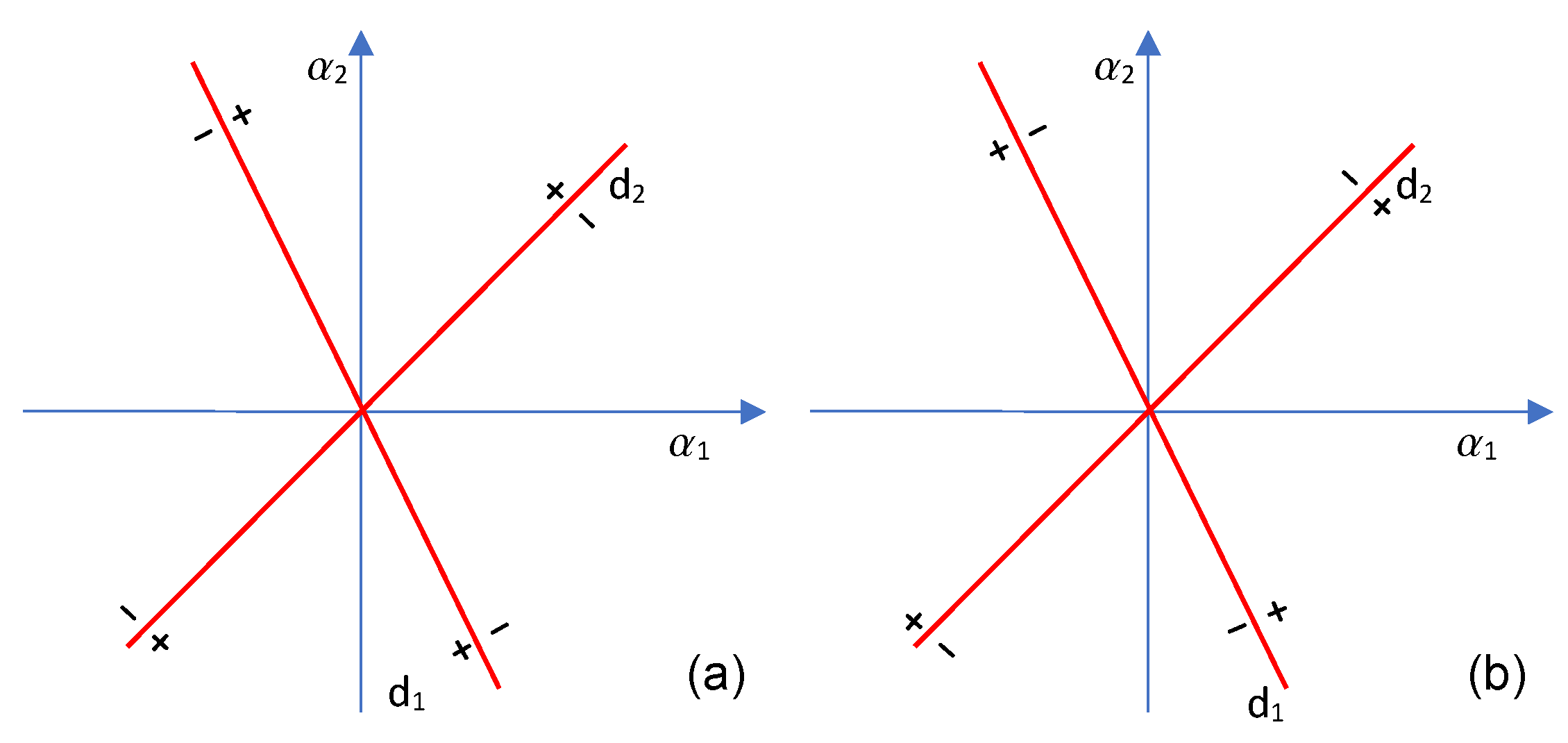

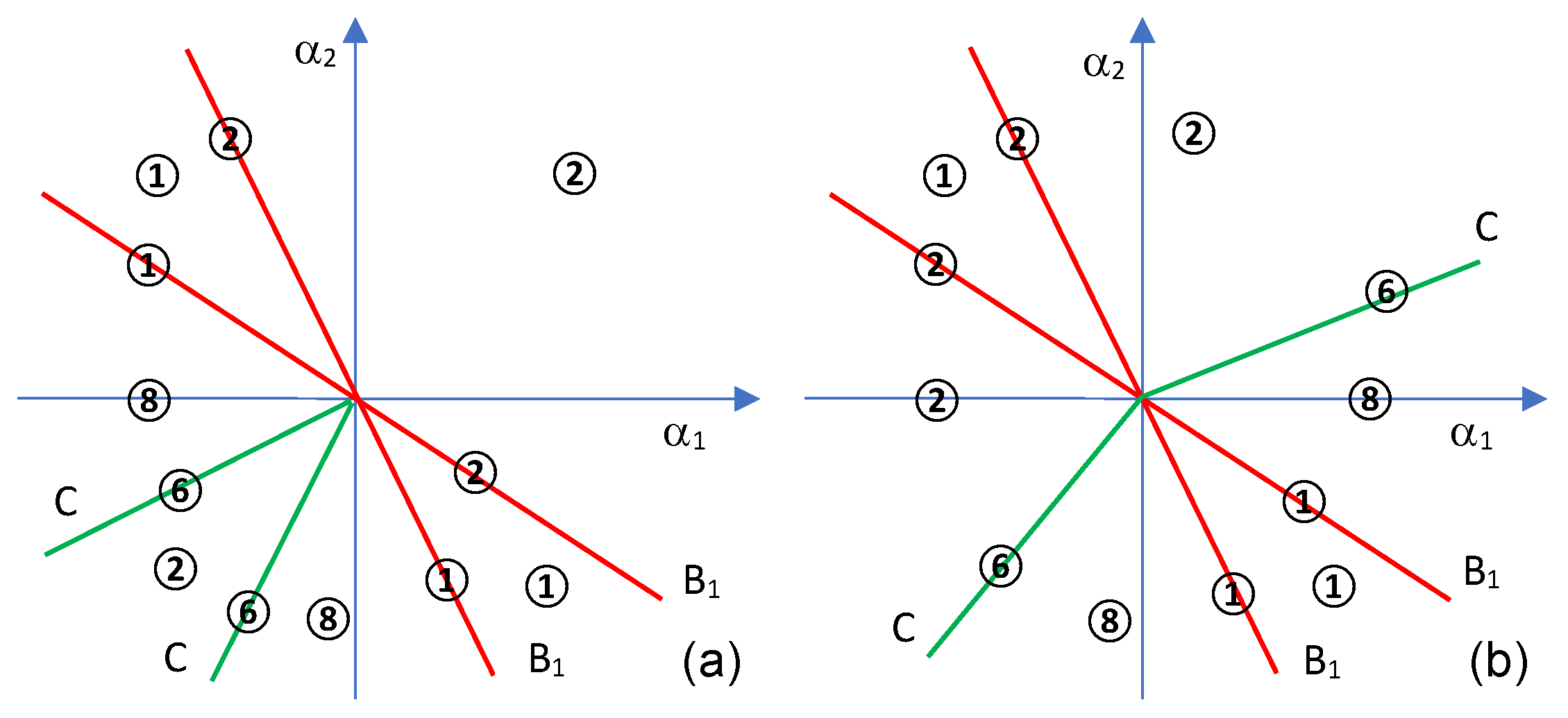

Remark 2. Figure A1 presents generic phase portraits “corresponding to different regions of the bifurcation diagrams, including the phase portraits on the bifurcation curves defined by ” [4] respectively, We summarize in Table A1 the correspondence between and “the generic phase portraits, respectively, different regions from bifurcation diagrams. When , then ” [4]. The sign of a 2-nd degree polynomial of two real variables is discussed below.

Let us consider a polynomial

Considering its associated one-variable-polynomial the signs of and are the same, for all the pairs , which are solutions of the equation,

We use the convention that

and the corresponding formula for

The sign of

is shown in

Figure 1a for

and in

Figure 1b for

where

for

4.1. Bifurcation Diagrams When the First Discriminant Is Strictly Positive

Bifurcation diagrams for are given in this subsection.

Firstly, we suppose that and we consider the polynomials of having the distinct real roots , respectively,

There will be considered the following cases of root ordering:

- I

:

- II

:

- III

:

- IV

:

- V

:

There is only one more case, which will not be taken into account, since it is a rotated case of I.

That ordering will be applied to the associated polynomials of

that is

; see

Section 4.

Theorem 2. The polynomials and have the following properties:

- 1.

- 2.

Proof. 1. by Viete relations

and by using the relations (

11),

which is positive since the polynomial

Indeed, the reduced discriminant of P is

2. by using Viete relations

Using (

11), one concludes that

□

Corollary 1. The cases II and V do not fulfill condition (2) of Theorem 2, and therefore they are eliminated.

Considering the possible sub-cases of I, III, and IV, depending on the signs of , one remarks that the numbers of sub-cases is halved by condition (1) of Theorem 2.

Theoretically, for any of the previous sub-cases, one must consider two possibilities, depending on the sign of the . However, the following theorem assigns a determined sign for any case.

Theorem 3. The sign of equals that one of

Proof. We calculate

By using the relation (

11):

Hence, the sign of is that of the expression in T:

The reduced discriminant of the last parenthesis is Therefore,

□

Corollary 2. By the previous theorem, one may specify the sign of in the following cases:

- 1.

I a, III b, IV b have

- 2.

I b, III a, IV a have

We may further reduce the sub-cases by the following theorems:

Theorem 4. Denoting it results that

Proof. equals, by (

11),

□

Corollary 3. In cases I a, III b, and IV b, M and N have different signs, and for the rest of the sub-cases, they have the same sign.

Theorem 5. The sum has no definite sign.

Proof. and by (

11),

is fixed, so

has a fixed sign. The second parenthesis has no fixed sign for all

since

□

Corollary 4. If have the same sign, then has a definite sign for all If do not have the same sign, then do not have a definite sign for all Hence, by Theorem 5 and Corollary 3, we may eliminate the cases I b, III a, and IV a. The remaining cases are I a, III b, and IV b.

By Corollary 4, the cases for the graphical representation of the lines are as follows:

- I a1

:

- I a2

:

- III b1

:

- III b2

:

- IV b1

:

- IV b2

:

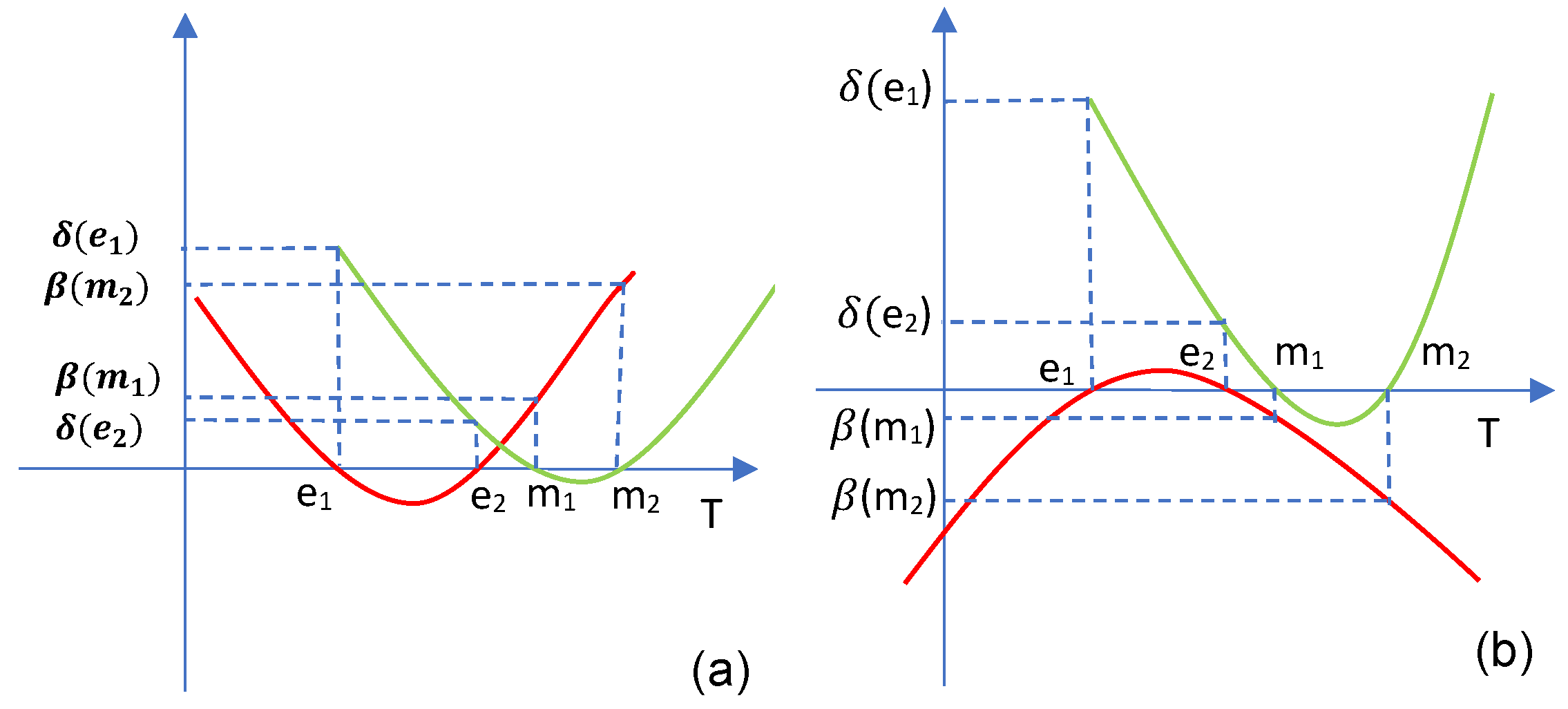

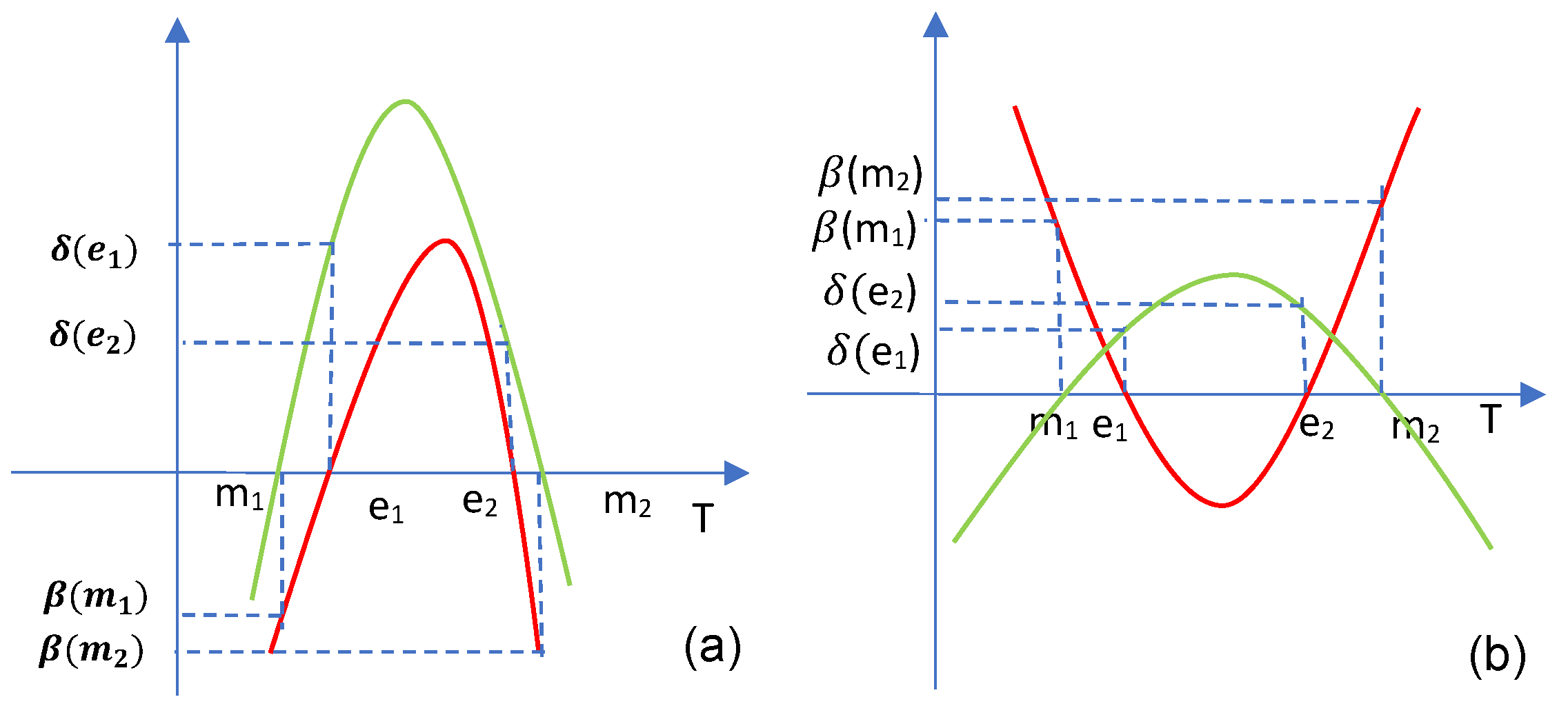

The bifurcation diagrams of cases I a1, III b1, and IV b2 are the same, represented in

Figure 5a, and the bifurcation diagrams of cases I a2, III b2, and IV b1 are the same represented in

Figure 5b.

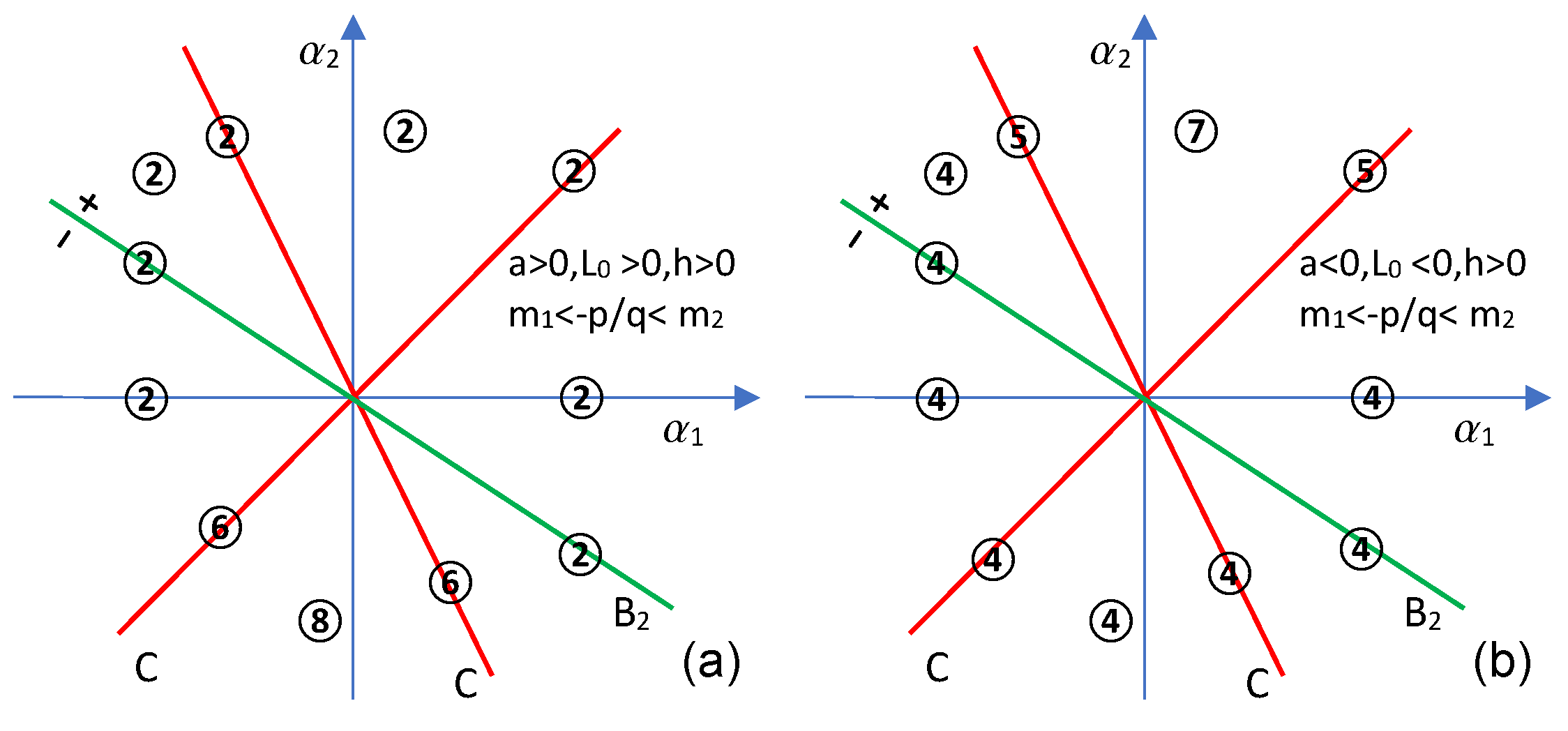

Remark 3. The case is solved by Theorem 1, Section 3 since if then for all That is, the single straight line which remains is and this case is trivial. 4.2. Bifurcation Diagrams When the First Discriminant Is Strictly Negative

Bifurcation diagrams for are given in this subsection.

Remark 4. If and then We will show that the single bifurcation curve is in this case.

We observe that and by we have that Taking into account Theorem 1, (3), we have that and

There are more two trivial bifurcation diagrams which are not taken into account due to their triviality:

Remark 5. - (a)

If and then the bifurcation diagrams contain only region 3.

- (b)

If and , then the bifurcation diagrams contain only region 1.

Proof of Remark 4. Using

results in

Taking into account that

, we obtain

Because

it follows that

However,

and by

we have that

Using Theorem 1, (3) and that , we have □

Case 4.2.1 When , and

We see that , and from , it follows that . Thus, the equation has two real distinct roots, We notice that

We consider the expression

By calculus, we obtain We replace further in the previous expression h by k by , and l by , and we have

Now using that

and

, we will find that

In this situation we have only the following two systems:

By solving these systems, we find only the solution because

In the previous case, two sub-cases arise:

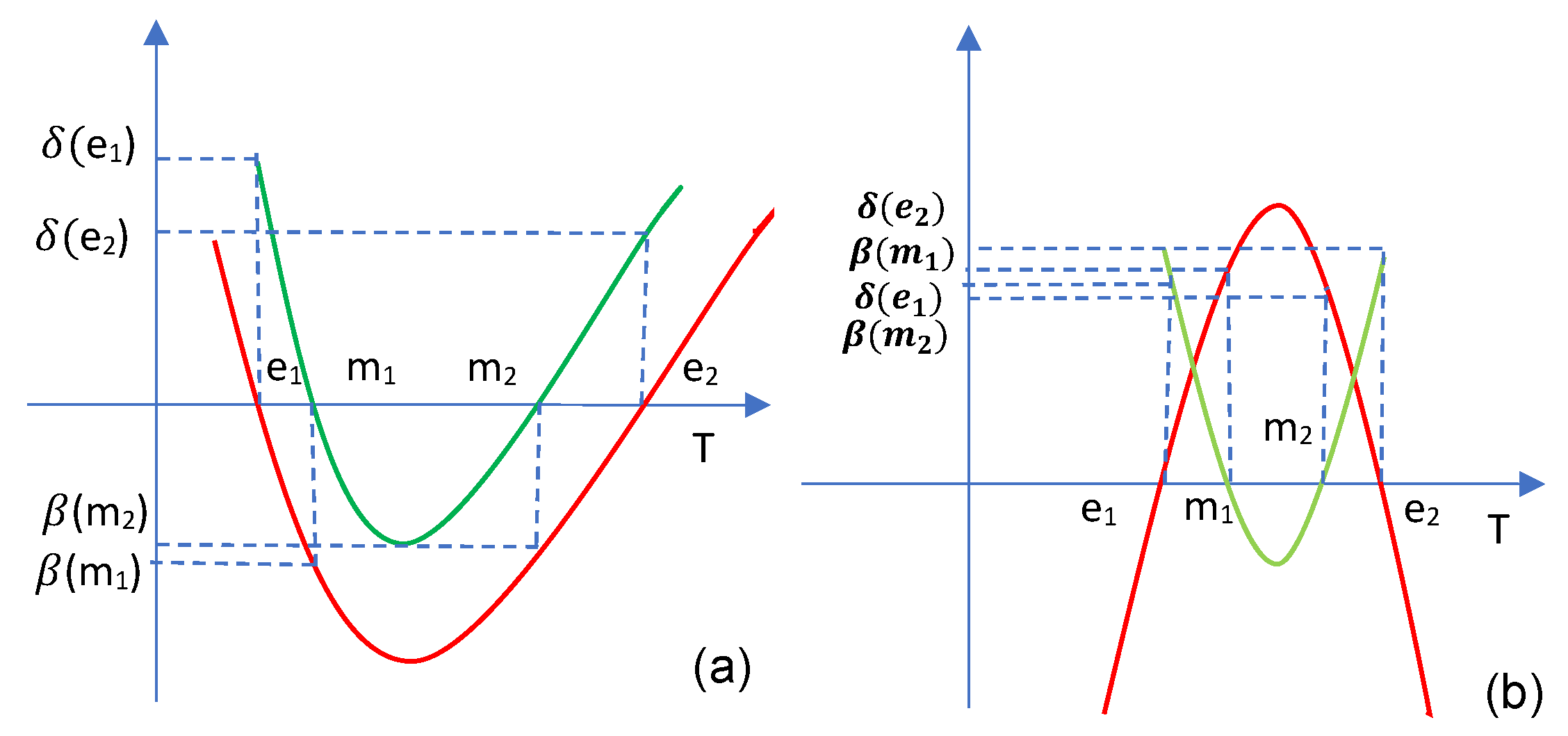

Remark 6. - (a)

If and , then the following bifurcation diagram appears in Figure 6a: - (b)

If and , then the following bifurcation diagram appears in Figure 6b:

Case 4.2.2 If

and

, then

and the equation

has two real and distinct roots:

Taking into account that and . We obtain this time that Now we compute also the sum, S, thus

From here, two cases arise.

When

first sub-case,

is equivalent to

and in this point we also have two possibilities:

(a) or (b)

In case (a), from we obtain and then

In case (b), from we have and further

This means that

and using that

, we obtain

Now, the second sub-case becomes and in this point, we also have two possibilities:

(a) or (b)

In case (a), from we obtain and then

In case (b), from we have and further

Therefore, now we have instead, and using that , we obtain

Here, it does not appear to be the case that

Case 4.2.2 I If , then and from here, using that , we obtain

There are other two more trivial bifurcation diagrams which were not taken into account due to their triviality.

Remark 7. - (a)

If and then the bifurcation diagram contain only the region 2 in the whole plane of coordinates,

Using that , , and taking into account that can have any sign, we see in Table A1 that for this configuration of signs will appear only the region 2. - (b)

If then the bifurcation diagram will contain only region 4 in the whole plane of coordinate

By the same reason, using that and taking into account that can have any sign, we see in Table A1 that for this configuration of signs, it will appear only in region 4.

4.2.2 II If

, then

However,

and therefore

has two distinct real roots

and

Because is not between and , we see that

Remark 8. In this case, the bifurcation diagrams are as in the case 4.2.1, Figure 6a,b, and only the conditions are different, not the dispersion of the regions. 5. Numerical Simulations

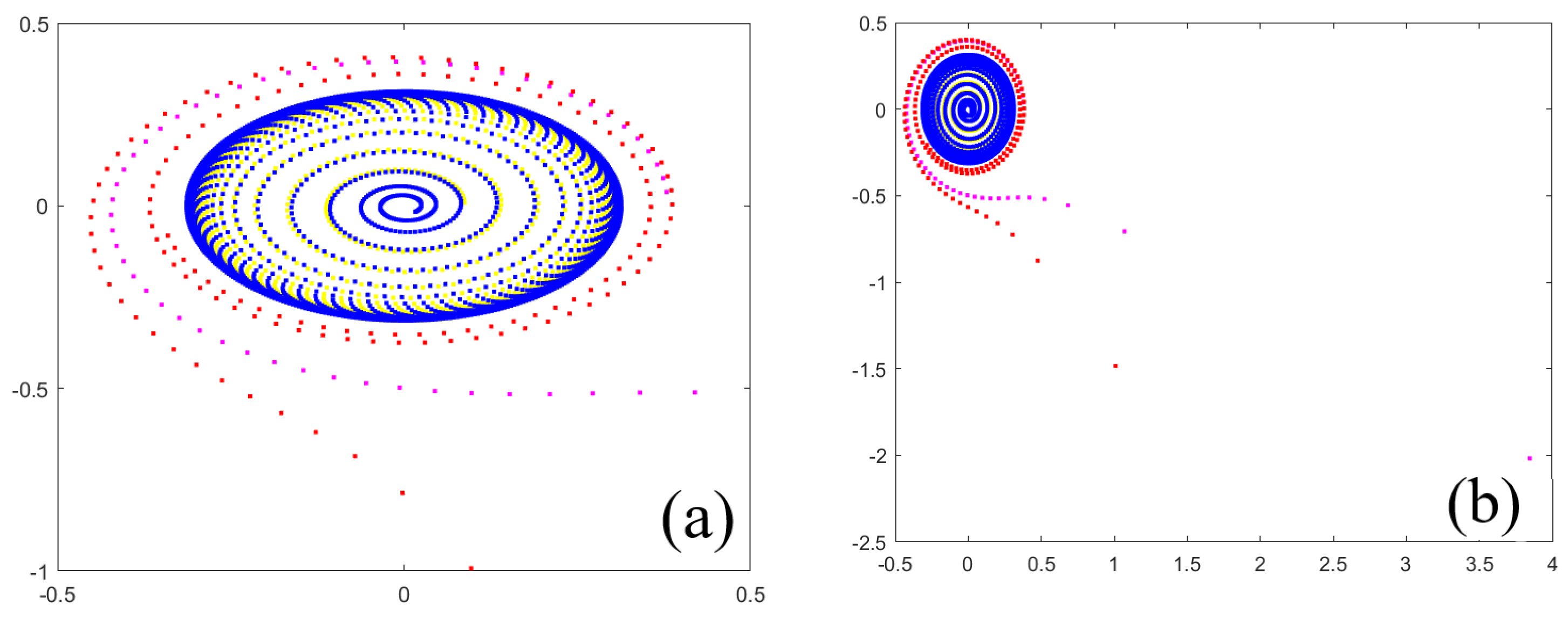

In order to numerically illustrate “the existence of closed invariant curves” [

4] in some of the studied cases, the Matlab software was used. In the particular case when the two-dimensional map is given in polar coordinates by

being sufficiently small and

we choose

Figure 7a,b shows the phase portraits 3 and 1 obtained when the conditions of Remark 5a,b are satisfied, respectively. In

Figure 7a, the magenta orbit starting from

approximates the invariant closed curve (invariant circle) from Theorem 1 [

4], being obtained for

steps starting from the outside of the circle. The blue orbit starts from

and it is also obtained for

, which approximates the invariant circle starting from the inside and staying inside the circle. The red orbit starts in

, approximates the invariant circle from the inside, and is obtained for

steps. The green orbit starts from

, from the outside of the invariant circle and approximates it. This is how the phase 3 portrait appears here, the conditions in Remark 5a, Case 4.2 being satisfied (

). For the invariant circle, the radius is

; in our case, having

, we are also in the conditions of Theorem 1 (2) (b) [

4]. We consider the particular case where the two-dimensional map is given in polar coordinates by

being sufficiently small,

It is observed that

, so the conditions in Remark 5b are satisfied, and then the bifurcation diagram contains only phase portrait 1 (corresponding to region 1). We choose 3 orbits starting from the points

and

of the colors magenta, red and blue, respectively, and which have

,

and

steps, respectively; see

Figure 7b. The magenta orbit moves away from the invariant circle and may escape to infinity, while the red orbit tends toward the origin

, and the blue orbit likewise tends toward the origin. In addition, the radius of the invariant circle will be

(the conditions of Theorem 1 (2), (a) being satisfied) (

).

Figure 7.

Numerical simulation for the map (

A7) and (

A8) with: (

a)

and

,

; (

b)

and

,

.

Figure 7.

Numerical simulation for the map (

A7) and (

A8) with: (

a)

and

,

; (

b)

and

,

.

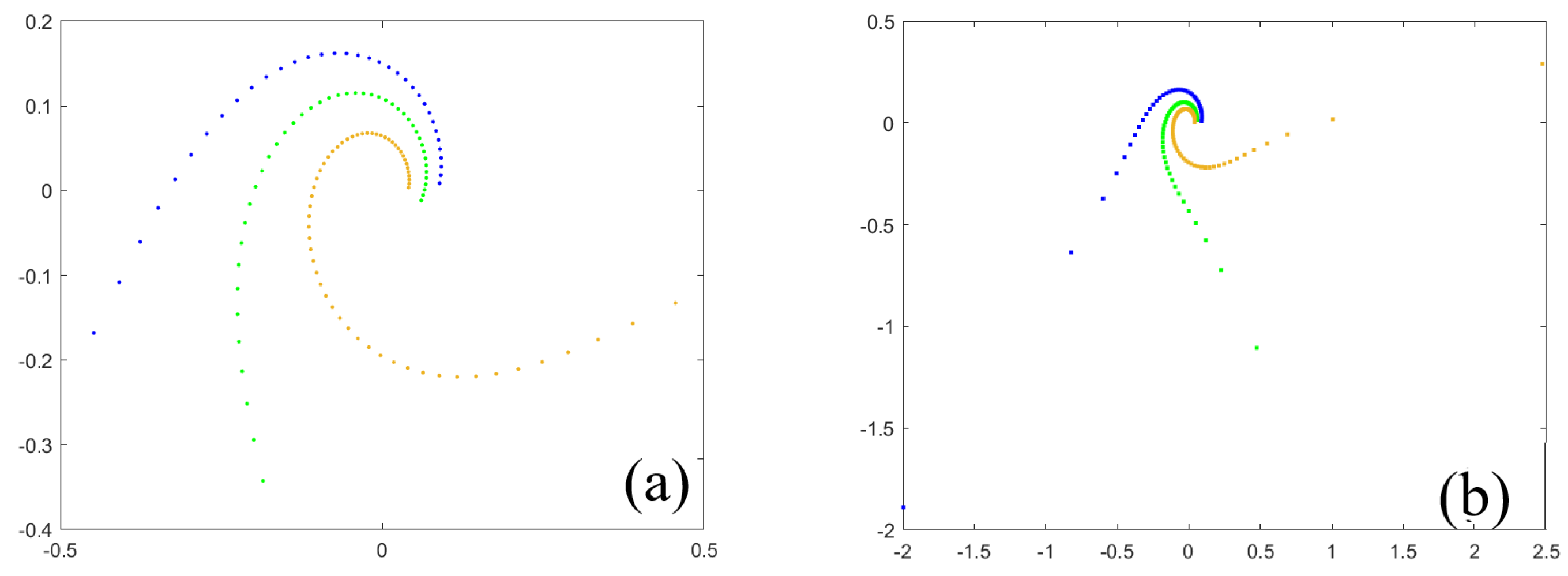

For

Figure 6a, we wanted to check on a particular case where the appearance of regions 2, 6, and 8 corresponds to phase portraits 2, 6, and 8. We consider the map given in polar coordinates by

being small enough

. We took

,

and we notice that the conditions are checked (

,

,

,

,

,

and

) to be on one of the straight lines that form the curve (C) in

Figure 6a, the point

being in quadrant IV, so it is region 6. For the orbits of blue, red, magenta and yellow colors from

Figure 8a, starting at points

,

,

and

, respectively, we consider

,

,

and

steps, respectively. It can be seen that the blue orbit approximates the invariant circle, the red orbit tends to infinity (if we increase the number of steps to

and

for the red and magenta curves, we obtain

Figure 8b), the magenta orbit, like the red one, tends at infinity moving away from the invariant circle, and the yellow orbit, like the blue one, approximates (tends to) the invariant circle. This proves that we have phase portrait 6, so region 6 (as in the figure) is in accordance with the theoretical results. More than that,

, is the radius of the invariant circle, and because

, the equation

has a double root.

However, with

and

, the point

is in quadrant I,

will be different from

and

, and in

Figure 6a, region 2 will appear. For the orbits of blue, green and brown colors starting from points

,

and

, respectively, the numbers of steps are considered

,

and

, respectively. The 3 orbits tend to infinity corresponding to phase 2 portrait (region 2); see

Figure 9a. If we take

,

and

instead of the previous 3 values, we obtain

Figure 9b, and it is observed that the last values increase a lot. Then, choosing

, the pair

is in quadrant III, and

will be different from

and

.

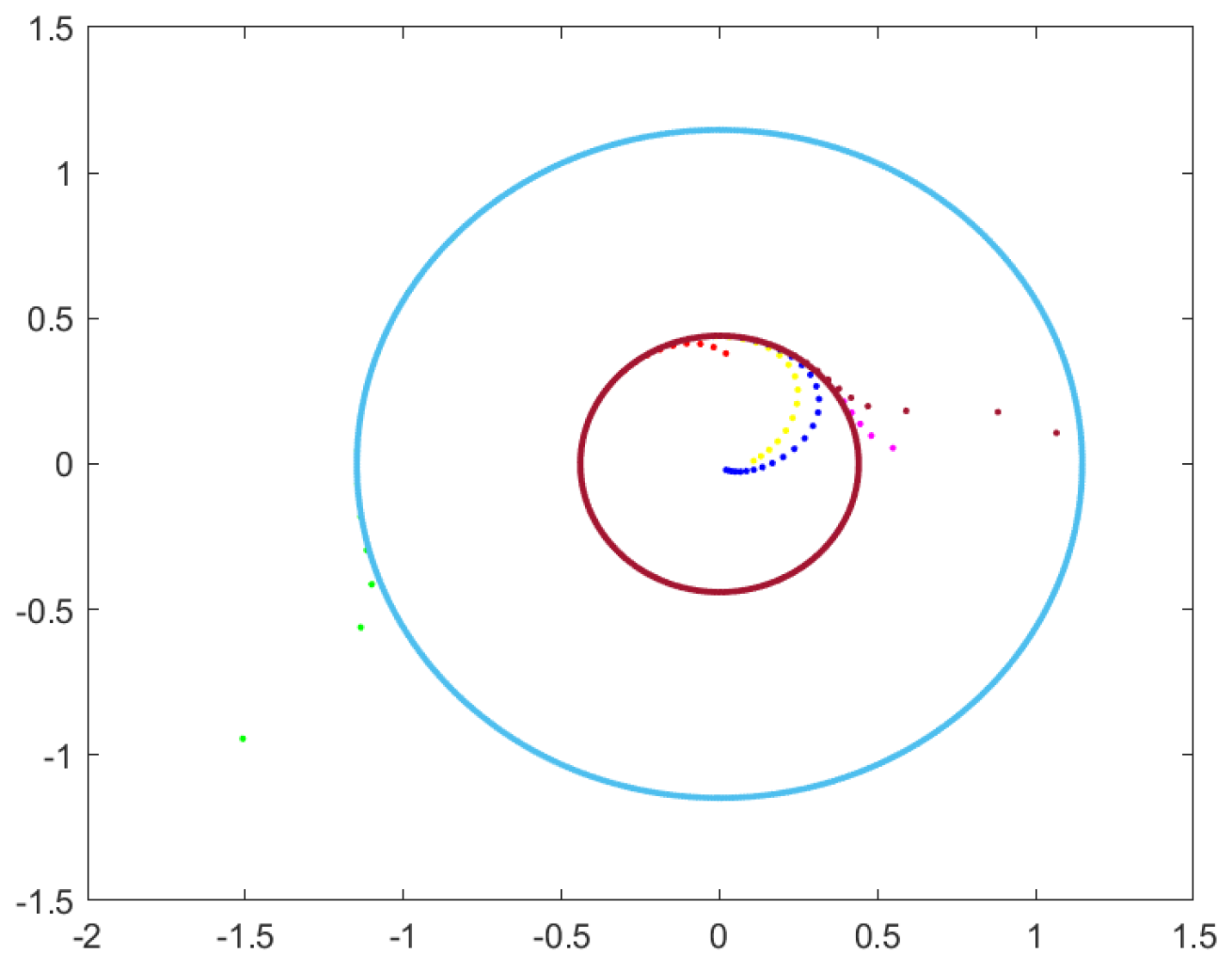

The six orbits start in

Figure 10 from din

,

,

,

,

and

having the colors yellow, magenta, red, green, blue and cherry, respectively, with steps

,

,

,

,

and

, respectively. The cyan-colored orbit is the outer invariant circle. The cherry and magenta orbits approximate the inner invariant circle from the outside, and the blue, yellow and red orbits approximate the inner invariant circle from the inside. The green orbit moves away from the outer invariant circle tending to infinity, thus observing that the orbits move away from the outer circle and tend toward the inner invariant circle. We thus have the portrait of phase 8, region 8. The radii of the two invariant circles are known from Theorem 1 [

4].