Abstract

The Horner and Goertzel algorithms are frequently used in polynomial evaluation. Each of them can be less expensive than the other in special cases. In this paper, we present a new compensated algorithm to improve the accuracy of the Goertzel algorithm by using error-free transformations. We derive the forward round-off error bound for our algorithm, which implies that our algorithm yields a full precision accuracy for polynomials that are not too ill-conditioned. A dynamic error estimate in our algorithm is also presented by running round-off error analysis. Moreover, we show the cases in which our algorithms are less expensive than the compensated Horner algorithm for evaluating polynomials. Numerical experiments indicate that our algorithms run faster than the compensated Horner algorithm in those cases while producing the same accurate results, and our algorithm is absolutely stable when the condition number is smaller than . An application is given to illustrate that our algorithm is more accurate than MATLAB’s function. The results show that the relative error of our algorithm is from to , and that of the was from to .

Keywords:

polynomial evaluation; goertzel algorithm; round-off error; error-free transformation; compensated algorithm; numerical stability MSC:

68U01

1. Introduction

Polynomial evaluation is ubiquitous in computational sciences and their applications, such as interpolation and approximation practices and signal processing. This article will investigate a broader situation of polynomial evaluation:

where . The nested-type algorithms are usually used to evaluate polynomials. The Horner algorithm is the most widely used polynomial evaluation algorithm [1]. In special cases, like and , the Goertzel algorithm that can be applied to compute the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) of specific indices in a vector [2,3] is less expensive the Horner algorithm. The numerical stability of the Horner and Goertzel algorithms was given by Wilkinson [4] and Smoktunowicz [5]. The computed results from these algorithms are arbitrarily less accurate than the working precision u when the polynomial is ill-conditioned due to the round-off errors in floating-point arithmetic. The relative accuracy of these algorithms verifies the following priori bound:

where is the computed result and is the condition number.

In order to improve the accuracy of double precision, Bailey [6] proposed a famous library for double-double and quad-double arithmetic. However, this library needs to normalize floating-point numbers in every operation, and thus the instruction level parallelism is affected [7,8]. The compensated algorithm is improved to solve this problem with the developments and applications of error-free transformation [9]. The relative accuracy of compensated algorithms verifies the following priori bound:

where is the computed result of a compensated algorithm.

Recently, compensated algorithms have been widely studied in evaluating polynomials. Graillat [10] proposed a compensated Horner algorithm that achieves full precision accuracy for polynomials that are not excessively ill-conditioned. Aside from that, he extended the error-free transformation and compensated Horner algorithm in complex floating-point arithmetic [11,12] and applied a compensated Horner algorithm to evaluate rational functions [13] and solve all polynomial roots [14]. Polynomial series represented in other basis were also considered, such as the Chebyshev form evaluated by a compensated Chenshaw algorithm [15], the Bernstein form evaluated by a compensated de Casteljau algorithm [16], and a compensated Volk and Schumaker(VS) algorithm [17]. Furthermore, the compensated idea is also applied to matrix multiplication to obtain more accurate results [18,19,20].

With the wide application of floating-point numbers and floating-point operations in numerical computing, the analysis of rounding errors has become the focus [21,22]. Running round-off errors are analyzed and applied to many algorithms of polynomial evaluation [23]. Delgado [17] proposed an adaptive evaluation algorithm by using the de Casteljau algorithm and compensated VS algorithms with a dynamic error estimate. Jiang [24] presented running round-off error analysis for evaluating elementary symmetric functions in real and complex floating-point arithmetic. Barrio [25] developed a more complete compensated algorithm library to evaluate orthogonal polynomial series with dynamic error estimates. In addition, error analysis can also be used for machine learning and the numerical solution of differential equations [26].

In this paper, our contributions are as follows:

- We design a new compensated Goertzel algorithm and prove that our algorithm can almost yield full working precision to evaluate polynomials (1);

- We propose dynamic error estimates, which can offer a sharper bound for our approach without considerably increasing its computing complexity;

- Numerical experiments show that our algorithm runs faster than the compensated Horner algorithm in some cases while keeping a similar precision accuracy;

- An application is given to illustrate that our algorithm outperforms MATLAB’s when dealing with the DFT.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces our compensated Goertzel algorithm. A dynamic error estimate is proposed in Section 3. Section 4 analyzes numerical experiment results and gives an application to illustrate that our algorithm outperforms them. Finally, the full paper is summarized in Section 5.

2. Goertzel Compensated Algorithm

We assume working with IEEE-754 floating-point standard [27] rounding to the nearest value in this paper. Let be the set of floating-point numbers, represent the complex number, and represent a floating-point operation. This part presents how to design the Goertzel compensated algorithm. First, the Goertzel algorithm and its relationship with the Clenshaw algorithm are listed. Then, the error-free transformations and sum of squares algorithm are recalled. At last, we present the compensated Goertzel algorithm.

2.1. Goertzel Algorithm

By assuming and , then we have a quadratic polynomial

where and . By dividing the polynomial in Equation (1) by that in Equation (4), we obtain

where

Thus, the evaluated result of the polynomial in Equation (1) is

Above Equations (5)–(7), we can find the Goertzel algorithm [2] with Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Polynomial evaluation by Goertzel algorithm |

Function:

Require: , Ensure:

for end |

In floating-point arithmetic, a backward error bound for the computed result of the polynomial evaluation by Algorithm 1 is presented by Smoktunowicz [5] as Theorem 1:

Theorem 1.

Assume for . Let . Then the Goertzel algorithm for evaluating the polynomial in Equation (1) is componentwise backward stable such that

where

In fact, Algorithm 1 is a special case of the Clenshaw algorithm [2,5]. When we let and , Algorithm 1 can be represented in Clenshaw form [28]:

According to the properties of the Chebyshev polynomial series [29] evaluated by the Clenshaw algorithm, we have

where and are Chebyshev polynomials of the first and second kinds, respectively. They satisfy

and

2.2. Error-Free Transformations and Sum of Squares Algorithm

The basic algorithms of error-free transformations are and , which were presented by Knuth [30] and Dekker [31], respectively. Graillat [11] extended the addition and multiplication to complex number cases, which are and , respectively. In this paper, we shall use a new product error-free transformation of one real and one complex floating-point number, which is called in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Error-free transformation of the product of real and complex floating-point numbers |

Function:

Require: , Ensure: |

The details of the error-free transformations above are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Error-free transformations, their properties and operation costs.

Furthermore, the sum of squares algorithm [32] is given in Algorithm 3. It requires 42 flops.

| Algorithm 3 Sum of squares by two floating-point numbers |

Function: Require:

Ensure: |

2.3. Compensated Goertzel Algorithm

Although Algorithm 1 is a special Clenshaw algorithm, computation via Equation (10) is more expensive. Thus, using the compensated Clenshaw algorithm [28] to express the compensated Goertzel algorithm is not a good idea. We design a compensated Goertzel algorithm by using , and algorithms to record the round-off errors.

Assume is a computed result in floating-point arithmetic, and its perturbation is such that

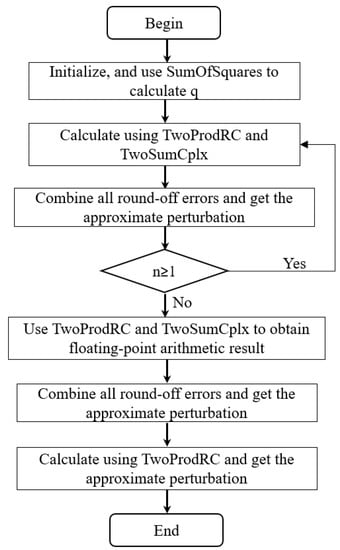

can find the approximate round-off error of q. Other round-off errors in Algorithm 1 can be accurately computed by error-free transformation algorithms and . Then, we can combine all round-off errors by and find the approximate perturbation of for in each loop. The loop ends using and to calculate and combines all round-off errors to obtain the approximate perturbation. The round-off error of should also be considered by . The compensated Goertzel algorithm is presented in Algorithm 4, and Figure 1 shows the flow chart of this algorithm.

| Algorithm 4 Polynomial evaluation by compensated Goertzel algorithm |

Function:

Require: , Ensure:

for end |

Figure 1.

The flowchart of the compensated Goertzel algorithm.

We remark that if , then we shall replace and with and in Algorithm 4, respectively.

3. Round-Off Error and Complexity Analysis

In this section, we consider the error bound and complexity of Algorithm 4 through Higham’s theories [33]. In our analysis, we assume that there is no computational overflow or underflow. First, we present the priori bound by forward round-off error analysis. Then, we show a dynamic error estimate by running round-off error analysis. At last, we compare the complexities of Horner, Goertzel, their compensated algorithms and the compensated Goertzel algorithm with a dynamic error estimate to evaluate the polynomial in Equation (1) in real and complex coefficients.

3.1. Forward Round-Off Error Analysis

Let ⧫ , and . Then, a floating-point computation obeys the model

where . We define

where and

for and . We assume that and in real arithmetic are denoted by , which will be used in our later analysis.

Lemma 1 summarizes the properties of the error-free transformations in Table 1:

Lemma 1.

For , verifies

In addition, verifies

For , verifies

Additionally, verifies

For , verifies

Proof.

Lemma 2 shows the property of Algorithm 3:

Lemma 2.

For , verifies

Proof.

According to Algorithm 3 and Table 1, . With Lemma 1, we obtain and . From Equations (15)–(17), we have

From Theorem 4.2 in [32], . □

Theorem 2 presents a priori error bound of Algorithm 4 to evaluate the polynomial in Equation (1) in complex floating-point arithmetic.

Theorem 2.

Assume for . Then, the relative forward round-off error bound in the compensated Goertzel algorithm for evaluting in floating-point arithmetic satisfies

Proof.

Assume the error of is e (i.e., ). Then, we have

and

where and are the error of and , respectively, such that

where for . Similarly, let

where

and

where for . Then, Equation (26) can be simplified as

In Algorithm 4, according to Lemmas 1 and 2, we obtain

for , and then

Then, by induction, we get

and

Assume that

Given this, then

It is easy to obtain that

Thus, with , we deduce Equation (25). □

3.2. Running Round-Off Error Analysis

Theorem 3 gives a running error bound of Algorithm 4 to evaluate the polynomial in Equation (1) in complex floating-point arithmetic:

Theorem 3.

Assume for . Then, the running round-off error bound in the compensated Goertzel algorithm for evaluting in floating-point arithmetic satisfies

where

Proof.

Assume e is the error of , i.e., . Let . Then, we have

Considering the round-off error in Algorithm 4, from Lemma 2, we have , and thus

By induction, we get

Assuming that , we have

From Equations (15)–(17) and (29), we get . Then, by Equations (56), (57) and (62), due to and , we deduce

□

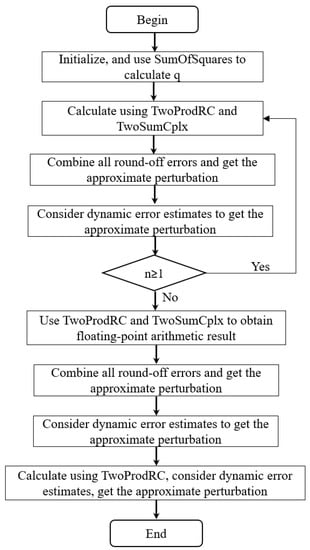

Considering a dynamic error estimate to evaluate the polynomial based on Theorem 3, we can improve Algorithm 4 into Algorithm 5, whose flowchart is shown in Figure 2. We can see from Algorithm 5 that a new approximate perturbation term is obtained by combining all the dynamic error estimates in each calculation, and participating in the following computation makes the final result more accurate.

Figure 2.

The flowchart of the compensated Goertzel algorithm with dynamic error estimates.

3.3. Computational Complexity

The and its compensated algorithm [12] are recalled in Algorithms 6 and 7. We shall use and instead of and , while the inputs of Algorithm 7 are real floating-point numbers. A comparison of the computational costs of Algorithms 1 and 4–7 is shown in Table 2. As we can see, each of the compensated algorithms (i.e., or ) can be less expensive than the others in different cases. For example, is half as expensive as when , and . For , and , the cost of is also less than that of . Even in these cases, costs less than . However, for , is twice as expensive as regardless of .

| Algorithm 5 Polynomial evaluation by compensated Goertzel algorithm with a dynamic error estimate |

Function:

Require: , Ensure: , for end |

Table 2.

Comparison of computational costs of and algorithms.

| Algorithm 6 Polynomial evaluation by the Horner algorithm |

Function:

Require: , Ensure:

for end |

| Algorithm 7 Polynomial evaluation by the compensated Horner algorithm |

Function:

Require: , Ensure: for end |

4. Numerical Experiments

In this section, we test the accuracy, performance and application of our algorithm. All numerical experiments are performed in IEEE-754 double precision as working precision.

4.1. Accuracy

The accuracy measurements in this part were found in MATLAB R2019b, and the exact results were obtained by the Symbolic Toolbox in order to compute the relative errors. As in [12], we considered the expanded form of the polynomial

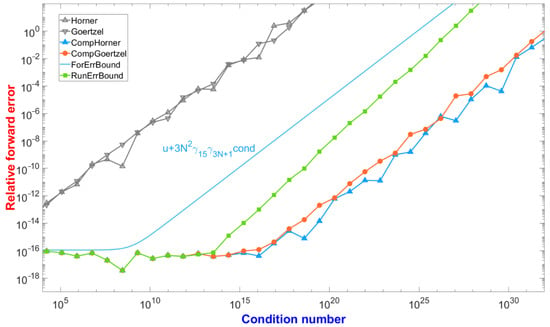

at for :42, while the condition number varied from to . The relative accuracy of the , , and algorithms as well as the theoretical bounds of in Theorems 2 and 3 are exhibited in Figure 3. We can observe that the algorithm, which had almost the same accuracy as the algorithm, was absolutely stable when the condition number was smaller than . Moreover, the numerical results and the error bounds had a good agreement, especially the running error bound, which was almost the same as the real relative errors, along with the results while the condition number was smaller than .

Figure 3.

Accuracy of evaluation of at for :42.

4.2. Running Time

In this part, we show the practical performance of the , , and algorithms in terms of measured computing time. The tests were performed in the following environments:

- Env1: Laptop with Intel Core i7-7700 CPU, 4 cores each at 3.6 GHz and with Microsoft Visual C++ 2012 with the default compiler option /od on Windows 7;

- Env2: Node of workstation with Intel Xeon E5-2697A CPU, 16 cores each at 2.6 GHz and with gcc 7.4.0 with the default compiler option-O0 on x86_64-Ubuntu-linux 18.04.

We generated the test polynomials with random coefficients in the interval , whose degree varied from 50 to 10,000 by a step of 50. The average time ratios for , , and are reported in Table 3 and Table 4, while the coefficients of the test polynomials were and , respectively. As we can see, was faster than in practice, especially when testing in Linux. We note the good agreement of the numerical and theoretical results except for while , , and in Env2. This is because takes more benefit than from the Fused-Multiply-and-Add instruction [34,35] and the instruction-level parallelism [7,8]. However, was still faster than in this case in Env1.

Table 3.

Theoretical computational complexity and measured running time ratios in .

Table 4.

Theoretical computational complexity and measured running time ratios in .

4.3. Application

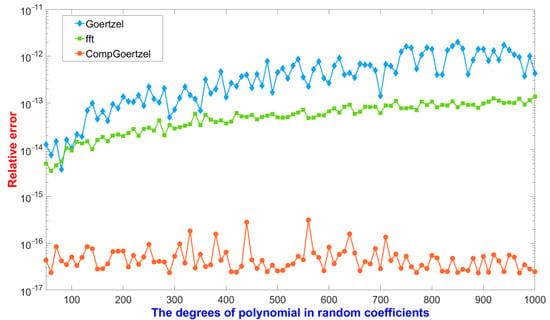

The test environment in this part was the same as the accuracy measurements. We considered the polynomial in Equation (1) with and . Then, the DFT, which could be computed by the function “fft” with the polynomial’s coefficients in MATLAB returned for . The algorithm can also compute the DFT with the polynomial’s coefficients of specific indices in a vector. Figure 4 shows the relative errors of , , and applied to polynomials whose degrees varied from 50 to 1000 by a step of 10 with random coefficients in the interval , where the relative error was defined as . In Figure 4, although was more accurate than , the relative errors of and were all increasing, while the degree of the polynomial grew. However, always obtained full-precision accurate results in this test, and the relative error of our algorithm was to , while the was from to .

Figure 4.

The relative errors of DFT for polynomials with random coefficients.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we presented a compensated Goertzel algorithm with dynamic error estimation to evaluate polynomials in complex floating-point arithmetic. The forward error analysis and numerical experiments show that the algorithm can yield full working precision accuracy. Furthermore, although the algorithm is as precise as the compensated Horner algorithm, it is quicker in certain situations. The algorithm also performed well in the application of computing the DFT of specific indices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L., P.D. and K.L.; methodology, C.L., P.D., Y.L. and H.J.; validation, C.L., K.L. and Z.Q.; formal analysis, K.L., Y.L. and H.J.; investigation, C.L., P.D. and H.J.; resources, Y.L. and Z.Q.; data curation, C.L. and P.D.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L., P.D., K.L. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, C.L., H.J. and Z.Q.; supervision, H.J. and Z.Q.; project administration, P.D. and H.J.; funding acquisition, P.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 61907034), the 173 program of China (2020-JCJQ-ZD-029), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFA0709803), the Science Challenge Project of China (TZ2016002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for providing valuable comments about our article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DFT | discrete Fourier transform |

| VS | Volk and Schumaker |

References

- Peña, J.M.; Sauer, T. On the multivariate Horner scheme. Siam J. Numer. Anal. 2000, 37, 1186–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentleman, W.M. An error analysis of Goertzel’s (Watt’s) method for computing Fourier coefficients. Comput. J. 1969, 12, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbery, A.C.R. Error analysis for Fourier series evaluation. Math. Comput. 1973, 27, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.H. Rounding Errors in Algebraic Processes; Courier Corporation: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Smoktunowicz, A.; Wróbel, I. On improving the accuracy of Horner’s and Goertzel’s algorithms. Numer. Algorithms 2005, 38, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.H. Library for Double-Double and Quad-Double Arithmetric. Available online: http://www.nersc.gov/dhbailey/mpdist/mpdist.html (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Louvet, N. Compensated Algorithms in Floating-Point Arithmetic: Accuracy, Validation, Performances; Université de Perpignan Via Domitia: Perpignan, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois, P.; Louvet, N. More Instruction Level Parallelism Explains the Actual Efficiency of Compensated Algorithm; Technical Report hal-00165020; DALI Research Team, University of Perpignan: Perpignan, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ogita, T.; Rump, S.M.; Oishi, S. Accurate sum and dot product. Siam J. Sci. Comput. 2005, 26, 1955–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graillat, S.; Langlois, P.; Louvet, N. Algorithms for accurate, validated and fast polynomial evaluation. Jpn. J. Ind. Appl. Math. 2009, 26, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graillat, S.; Morain, V. Error-free transformations in real and complex floating-point arithmetic. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Nonlinear Theory and Its Applications, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 16–19 September 2007; pp. 341–344. [Google Scholar]

- Graillat, S.; Morain, V. Accurate summation, dot product and polynomial evaluation in complex floating-point arithmetic. Inf. Comput. 2012, 216, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graillat, S. An accurate algorithm for evaluating rational functions. Appl. Math. Comput. 2018, 337, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, T.; Graillat, S. On a Compensated Ehrlich-Aberth Method for the Accurate Computation of All Polynomial Roots. Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03335604 (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Jiang, H.; Barrio, R.; Li, H.; Liao, X.; Cheng, L.; Su, F. Accurate evaluation of a polynomial in Chebyshev form. Appl. Math. Comput. 2011, 217, 9702–9716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Li, S.; Cheng, L.; Su, F. Accurate evaluation of a polynomial and its derivative in Bernstein form. Comput. Math. Appl. 2010, 60, 744–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Delgado, J.; Peña, J.M. Algorithm 960: POLYNOMIAL: An Object-Oriented Matlab Library of Fast and Efficient Algorithms for Polynomials. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2016, 42, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazal, N.Y.; Mukhlash, I.; Sanjoyo, B.A.; Hidayat, N.; Ozaki, K. Extended use of error-free transformation for real matrix multiplication to complex matrix multiplication. Siam J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1821, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, K. Error-free transformation of matrix multiplication for multi-precision computations. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Scientific Computing, Computer Arithmetic, and Verified Numerical Computations, Szeged, Hungary, 13–15 September 2021; Volume 33. [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki, K. An Error-Free Transformation for Matrix Multiplication with Reproducible Algorithms and Divide and Conquer Methods. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1490, 012062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozaki, K.; Ogita, T. The Essentials of verified numerical computations, rounding error analyses, interval arithmetic, and error-free transformations. Nonlinear Theory Its Appl. 2020, 11, 279–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, P.; Higham, D.J.; Higham, N.J. Accurately computing the log-sum-exp and softmax functions. IMA J. Numer. Anal. 2021, 41, 2311–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, J.; Peña, J.M. Running relative error for the evaluation of polynomials. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2009, 31, 3905–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Graillat, S.; Barrio, R.; Yang, C. Accurate, validated and fast evaluation of elementary symmetric functions and its application. Appl. Math. Comput. 2016, 273, 1160–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrio, R.; Du, P.; Jiang, H.; Serrano, S. ORTHOPOLY: A library for accurate evaluation of series of classical orthogonal polynomials and their derivatives. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2018, 231, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croci, M.; Fasi, M.; Higham, N.J.; Mary, T.; Mikaitis, M. Stochastic rounding: Implementation, error analysis and applications. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2022, 9, 211631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Standard 754-2008; Standard for Binary Floating Point Arithmetic. ANSI: New York, NY, USA, 2008.

- Clenshaw, C.W. A note on the summation of Chebyshev series. Math. Comput. 1955, 9, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegö, G. Orthogonal Polynomials; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Knuth, D.E. The Art of Computer Programming: Seminumerical Algorithms, 3rd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, T.J. A floating-point technique for extending the available precision. Numer. Math. 1971, 18, 224–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graillat, S.; Lauter, C.; Tang, P.T.; Yamanaka, N.; Oishi, S. Efficient Calculations of Faithfully Rounded I2-Norms of n-Vectors. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2015, 41, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, N.J. Accuracy and Stability of Numerical Algorithms, 2nd ed.; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM): Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Markstein, P. IA-64 and Elementary Functions: Speed and Precision; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nievergelt, Y. Scalar fused multiply-add instructions produce floating-point matrix arithmetic provably accurate to the penultimate digit. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 2003, 29, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).