Comprehensive Insights into Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes from Protein Network, Canonical Pathway, Phosphorylation and Antimicrobial Peptide Signatures of Human Serum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Subjects and Sample Collection

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. LC-MS Analyses

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Network Analysis

2.6. Examination of AMPs

2.7. Ingenuity Pathway Analyis®

2.8. Kinome Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Proteomics Analysis of Serum Samples

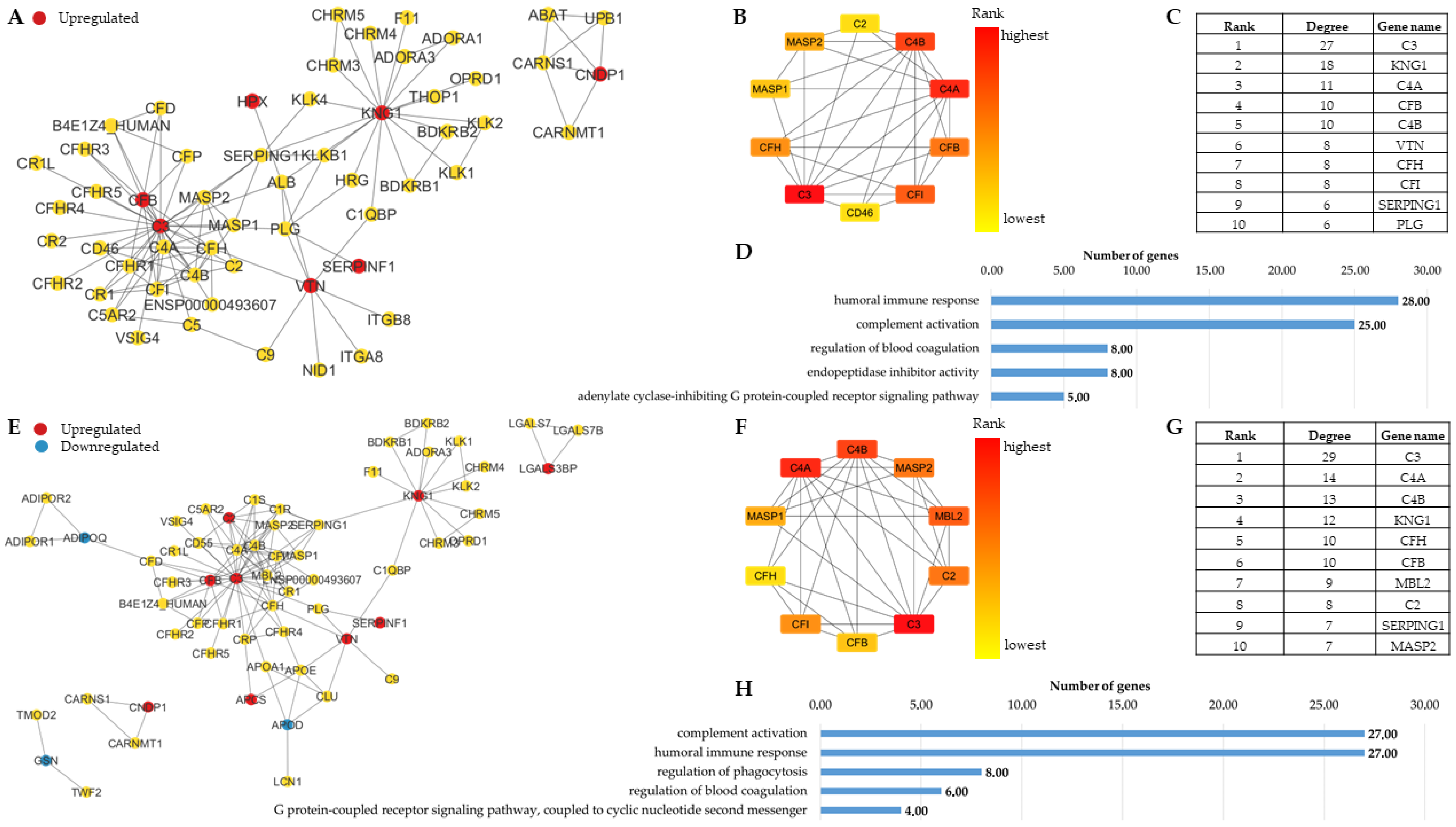

3.1.1. Network Analysis Highlights the Similarities in the Molecular Background of Obesity and T2D

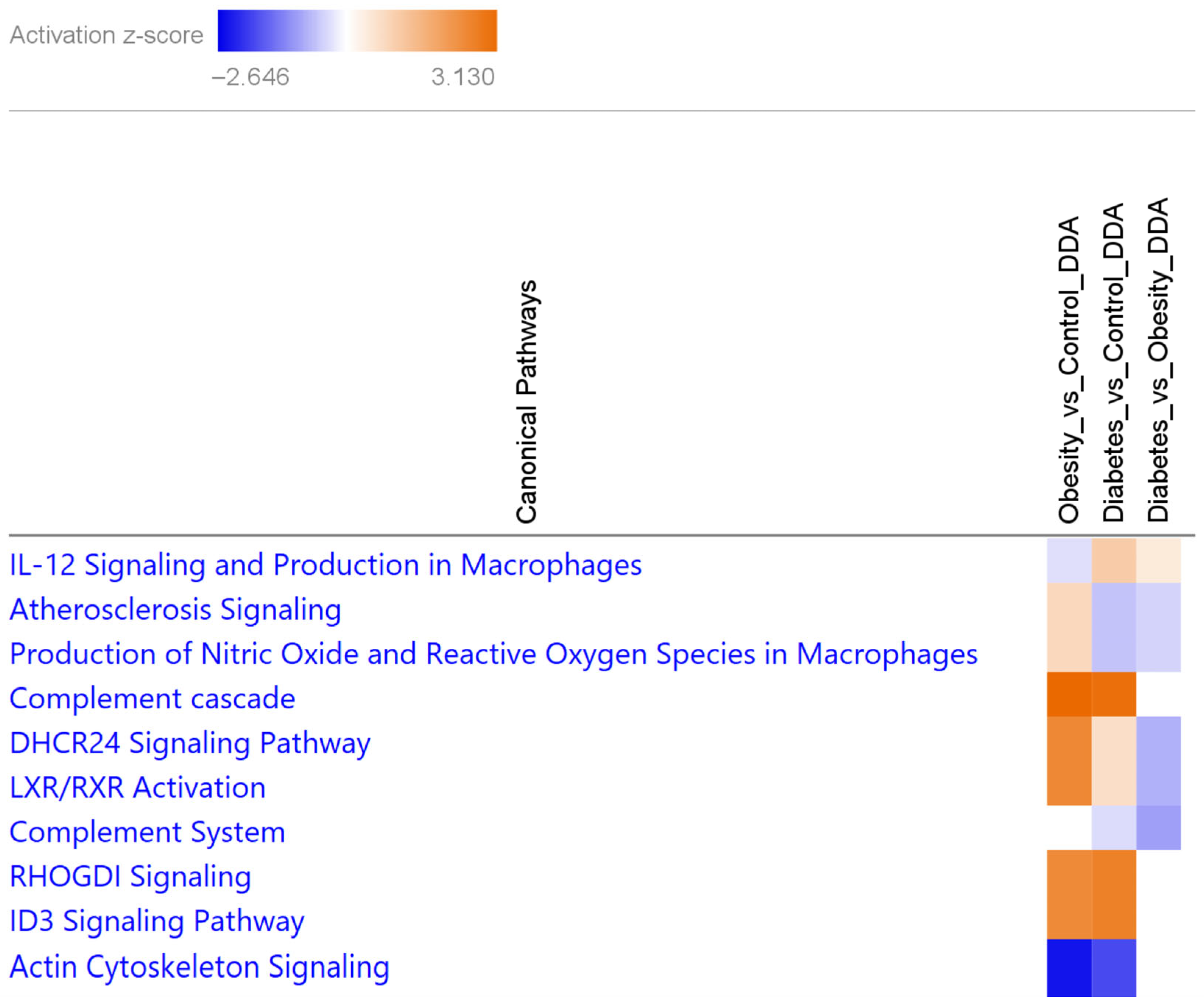

3.1.2. Canonical Pathways Characteristic of Obesity and T2D Show the Differential Involvement of Lipid Metabolism and Atherosclerosis Signaling in T2D

3.2. AMPs Indicate the Common Proteomic Landscape of Lipid Metabolism and Immune Regulation in Obesity and T2D

3.3. Phosphoproteomics Analysis of Non-Depleted Human Serum Samples Complements the Proteomics Results and Identifies Further Functions and Proteins Characteristic to Obesity or T2D

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, L.; Magliano, D.J.; Zimmet, P.Z. The Worldwide Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—Present and Future Perspectives. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2012, 8, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas 11th Edition 2025. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Almgren, P.; Lehtovirta, M.; Isomaa, B.; Sarelin, L.; Taskinen, M.R.; Lyssenko, V.; Tuomi, T.; Groop, L. for the Botnia Study Group Heritability and Familiality of Type 2 Diabetes and Related Quantitative Traits in the Botnia Study. Diabetologia 2011, 54, 2811–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, M.I. Genomics, Type 2 Diabetes, and Obesity. N Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 2339–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willemsen, G.; Ward, K.J.; Bell, C.G.; Christensen, K.; Bowden, J.; Dalgård, C.; Harris, J.R.; Kaprio, J.; Lyle, R.; Magnusson, P.K.E.; et al. The Concordance and Heritability of Type 2 Diabetes in 34,166 Twin Pairs from International Twin Registers: The Discordant Twin (DISCOTWIN) Consortium. Twin Res. Hum. Genet. 2015, 18, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ley, S.H.; Hu, F.B. Global Aetiology and Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.; Peeters, A.; de Courten, M.; Stoelwinder, J. The Magnitude of Association between Overweight and Obesity and the Risk of Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2010, 89, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, J.; Bain, S.; Kanamarlapudi, V. A Review of Current Trends with Type 2 Diabetes Epidemiology, Aetiology, Pathogenesis, Treatments and Future Perspectives. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 3567–3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.-Z.; Lu, W.; Zong, X.-F.; Ruan, H.-Y.; Liu, Y. Obesity and Hypertension (Review). Exp. Ther. Med. 2016, 12, 2395–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaturu, S. Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. J. Diabetes Mellit. 2011, 1, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A.R.; Sesso, H.D.; Lee, I.M.; Cook, N.R.; Manson, J.E.; Buring, J.E.; Gaziano, J.M. Relationship of Physical Activity vs Body Mass Index with Type 2 Diabetes in Women. JAMA 2004, 292, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eeg-Olofsson, K.; Cederholm, J.; Nilsson, P.M.; Zethelius, B.; Nunez, L.; Gudbjörnsdóttir, S.; Eliasson, B. Risk of Cardiovascular Disease and Mortality in Overweight and Obese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: An Observational Study in 13,087 Patients. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakkis, J.I.; Weir, M.R. Obesity and Kidney Disease. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2018, 61, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, J.S.; Vilaca, T. Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes and Bone in Adults. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2017, 100, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azrad, M.; Blair, C.K.; Rock, C.L.; Sedjo, R.L.; Wolin, K.Y.; Demark-Wahnefried, W. Adult Weight Gain Accelerates the Onset of Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 176, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, J.; Jaques, B.; Chattopadyhay, D.; Lochan, R.; Graham, J.; Das, D.; Aslam, T.; Patanwala, I.; Gaggar, S.; Cole, M.; et al. Hepatocellular Cancer: The Impact of Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes and a Multidisciplinary Team. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreras-Torres, R.; Johansson, M.; Gaborieau, V.; Haycock, P.C.; Wade, K.H.; Relton, C.L.; Martin, R.M.; Davey Smith, G.; Brennan, P. The Role of Obesity, Type 2 Diabetes, and Metabolic Factors in Pancreatic Cancer: A Mendelian Randomization Study. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djx012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, V.Z.; Libby, P. Obesity, Inflammation, and Atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2009, 6, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.; Lyon, C.J.; Bergin, S.; Caligiuri, M.A.; Hsueh, W.A. Obesity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2016, 11, 421–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karra, P.; Winn, M.; Pauleck, S.; Bulsiewicz-Jacobsen, A.; Peterson, L.; Coletta, A.; Doherty, J.; Ulrich, C.M.; Summers, S.A.; Gunter, M.; et al. Metabolic Dysfunction and Obesity-Related Cancer: Beyond Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome. Obesity 2022, 30, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bays, H.E.; Kirkpatrick, C.F.; Maki, K.C.; Toth, P.P.; Morgan, R.T.; Tondt, J.; Christensen, S.M.; Dixon, D.L.; Jacobson, T.A. Obesity, Dyslipidemia, and Cardiovascular Disease: A Joint Expert Review from the Obesity Medicine Association and the National Lipid Association 2024. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2024, 18, e320–e350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosli, R.H.; Mosli, H.H. Obesity and Morbid Obesity Associated with Higher Odds of Hypoalbuminemia in Adults without Liver Disease or Renal Failure. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2017, 10, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Muñoz, A.; Motahari-Rad, H.; Martin-Chaves, L.; Benitez-Porres, J.; Rodriguez-Capitan, J.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, A.; Insenser, M.; Tinahones, F.J.; Murri, M. A Systematic Review of Proteomics in Obesity: Unpacking the Molecular Puzzle. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2024, 13, 403–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doumatey, A.P.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, M.; Prieto, D.; Rotimi, C.N.; Adeyemo, A. Proinflammatory and Lipid Biomarkers Mediate Metabolically Healthy Obesity: A Proteomics Study. Obesity 2016, 24, 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosedale, D.E.; Sharp, T.; de Graff, A.; Grainger, D.J. The Remarkable Similarity in the Serum Proteome between Type 2 Diabetics and Controls. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, H.; Kou, M.; Heianza, Y.; Fonseca, V.; Qi, L. Proteomic Signature of BMI and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes 2024, 74, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundsten, T.; Eberhardson, M.; Göransson, M.; Bergsten, P. The Use of Proteomics in Identifying Differentially Expressed Serum Proteins in Humans with Type 2 Diabetes. Proteome Sci. 2006, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, R.-N.; Shen, P.-T.; Lin, H.Y.-H.; Liang, S.-S. Shotgun Proteomic Analysis Using Human Serum from Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2023, 43, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.Y.; Osman, J.; Low, T.Y.; Jamal, R. Plasma/Serum Proteomics: Depletion Strategies for Reducing High-Abundance Proteins for Biomarker Discovery. Bioanalysis 2019, 11, 1799–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrera, I.C.; Kleiner, O. Application of Mass Spectrometry in Proteomics. Biosci. Rep. 2005, 25, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoffmann, E.S.V. Mass Spectrometry: Principles and Applications, 3rd ed.; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Chichester, England, 2007; ISBN 978-0-470-03310-4. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.C.; MacCoss, M.J. Shotgun Proteomics: Tools for the Analysis of Complex Biological Systems. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther. 2002, 4, 242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, S.; Taylor, P.P.; Han, Z.; Moran, M.F.; Ma, B. Data Dependent-Independent Acquisition (DDIA) Proteomics. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 3230–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Distler, U.; Kuharev, J.; Navarro, P.; Levin, Y.; Schild, H.; Tenzer, S. Drift Time-Specific Collision Energies Enable Deep-Coverage Data-Independent Acquisition Proteomics. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalló, G.; Kumar, A.; Tőzsér, J.; Csősz, É. Chemical Barrier Proteins in Human Body Fluids. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahar, B.; Madonna, S.; Das, A.; Albanesi, C.; Girolomoni, G. Immunomodulatory Role of the Antimicrobial LL-37 Peptide in Autoimmune Diseases and Viral Infections. Vaccines 2020, 8, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otvos, L. Immunomodulatory Effects of Anti-Microbial Peptides. Et Immunol. Hung. 2016, 63, 257–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagener, J.; Schneider, J.J.; Baxmann, S.; Kalbacher, H.; Borelli, C.; Nuding, S.; Küchler, R.; Wehkamp, J.; Kaeser, M.D.; Mailänder-Sanchez, D.; et al. A Peptide Derived from the Highly Conserved Protein GAPDH Is Involved in Tissue Protection by Different Antifungal Strategies and Epithelial Immunomodulation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2013, 133, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mowafy, M.; Elgaml, A.; Abass, N.; Mousa, A.A.; Amin, M.N. The Antimicrobial Peptide Alpha Defensin Correlates to Type 2 Diabetes via the Advanced Glycation End Products Pathway. Afr. Health Sci. 2022, 22, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vela, D.; Sopi, R.B.; Mladenov, M. Low Hepcidin in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Examining the Molecular Links and Their Clinical Implications. Can. J. Diabetes 2018, 42, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, M.; Soto, N.; Arredondo-Olguín, M. Association between Ferritin and Hepcidin Levels and Inflammatory Status in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity. Nutrition 2015, 31, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozlu, N.; Akten, B.; Timm, W.; Haseley, N.; Steen, H.; Steen, J.A.J. Phosphoproteomics. WIREs Syst. Biol. Med. 2010, 2, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engholm-Keller, K.; Larsen, M.R. Technologies and Challenges in Large-Scale Phosphoproteomics. Proteomics 2013, 13, 910–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimsrud, P.A.; Swaney, D.L.; Wenger, C.D.; Beauchene, N.A.; Coon, J.J. Phosphoproteomics for the Masses. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010, 5, 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiyama, N.; Imamura, H.; Ishihama, Y. Large-Scale Discovery of Substrates of the Human Kinome. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 10503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harsha, H.C.; Pandey, A. Phosphoproteomics in Cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2010, 4, 482–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.; Tonelli, F.; Ito, G.; Davies, P.; Trost, M.; Vetter, M.; Wachter, S.; Lorentzen, E.; Duddy, G.; Wilson, S.; et al. Phosphoproteomics Reveals That Parkinson’s Disease Kinase LRRK2 Regulates a Subset of Rab GTPases. eLife 2016, 5, e12813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammer, E.B.; Lee, A.K.; Duong, D.M.; Gearing, M.; Lah, J.J.; Levey, A.I.; Seyfried, N.T. Quantitative Phosphoproteomics of Alzheimer’s Disease Reveals Cross-Talk between Kinases and Small Heat Shock Proteins. Proteomics 2015, 15, 508–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thimmappa, P.Y.; Nair, A.S.; Najar, M.A.; Mohanty, V.; Shastry, S.; Prasad, T.S.K.; Joshi, M.B. Quantitative Phosphoproteomics Reveals Diverse Stimuli Activate Distinct Signaling Pathways during Neutrophil Activation. Cell Tissue Res. 2022, 389, 241–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, J.K.; Lindqvist, C.B.; Jessen, S.; García-Ureña, M.; Ehrlich, A.M.; Schlabs, F.; Quesada, J.P.; Schmalbruch, J.H.; Small, L.; Thomassen, M.; et al. Insulin and Exercise-Induced Phosphoproteomics of Human Skeletal Muscle Identify REPS1 as a New Regulator of Muscle Glucose Uptake. Cell Rip. Med. 2025, 4, 102163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunez Lopez, Y.O.; Iliuk, A.; Petrilli, A.M.; Glass, C.; Casu, A.; Pratley, R.E. Proteomics and Phosphoproteomics of Circulating Extracellular Vesicles Provide New Insights into Diabetes Pathobiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, Y.-K.; Iliuk, A.B.; Tao, W.A. Mass Spectrometry-Based Phosphoproteomics in Clinical Applications. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 163, 117066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliuk, A.B.; Arrington, J.V.; Tao, W.A. Analytical Challenges Translating Mass Spectrometry-Based Phosphoproteomics from Discovery to Clinical Applications. Electrophoresis 2014, 35, 3430–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demichev, V.; Messner, C.B.; Vernardis, S.I.; Lilley, K.S.; Ralser, M. DIA-NN: Neural Networks and Interference Correction Enable Deep Proteome Coverage in High Throughput. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leinonen, R.; Diez, F.G.; Binns, D.; Fleischmann, W.; Lopez, R.; Apweiler, R. UniProt Archive. Bioinformatics 2004, 20, 3236–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swift, M.L. GraphPad Prism, Data Analysis, and Scientific Graphing. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1997, 37, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Nastou, K.C.; Lyon, D.; Kirsch, R.; Pyysalo, S.; Doncheva, N.T.; Legeay, M.; Fang, T.; Bork, P.; et al. The STRING Database in 2021: Customizable Protein–Protein Networks, and Functional Characterization of User-Uploaded Gene/Measurement Sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D605–D612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindea, G.; Mlecnik, B.; Hackl, H.; Charoentong, P.; Tosolini, M.; Kirilovsky, A.; Fridman, W.-H.; Pagès, F.; Trajanoski, Z.; Galon, J. ClueGO: A Cytoscape Plug-in to Decipher Functionally Grouped Gene Ontology and Pathway Annotation Networks. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1091–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalló, G.; Bertalan, P.M.; Márton, I.; Kiss, C.; Csősz, É. Salivary Chemical Barrier Proteins in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma—Alterations in the Defense Mechanism of the Oral Cavity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.-H.; Chen, S.-H.; Wu, H.-H.; Ho, C.-W.; Ko, M.-T.; Lin, C.-Y. cytoHubba: Identifying Hub Objects and Sub-Networks from Complex Interactome. BMC Syst. Biol. 2014, 8, S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vadadokhau, U.; Varga, I.; Káplár, M.; Emri, M.; Csősz, É. Examination of the Complex Molecular Landscape in Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, A.; Green, J.; Pollard, J.; Tugendreich, S. Causal Analysis Approaches in Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.L.; Yaron, T.M.; Huntsman, E.M.; Kerelsky, A.; Song, J.; Regev, A.; Lin, T.-Y.; Liberatore, K.; Cizin, D.M.; Cohen, B.M.; et al. An Atlas of Substrate Specificities for the Human Serine/Threonine Kinome. Nature 2023, 613, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatterale, F.; Longo, M.; Naderi, J.; Raciti, G.A.; Desiderio, A.; Miele, C.; Beguinot, F. Chronic Adipose Tissue Inflammation Linking Obesity to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Front. Physiol. 2020, 10, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohm, T.V.; Meier, D.T.; Olefsky, J.M.; Donath, M.Y. Inflammation in Obesity, Diabetes, and Related Disorders. Immunity 2022, 55, 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, N.; Legrand-Poels, S.; Piette, J.; Scheen, A.J.; Paquot, N. Inflammation as a Link between Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2014, 105, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlazlo, N.; van Greevenbroek, M.M.J.; Ferreira, I.; Feskens, E.J.M.; van der Kallen, C.J.H.; Schalkwijk, C.G.; Bravenboer, B.; Stehouwer, C.D.A. Complement Factor 3 Is Associated with Insulin Resistance and With Incident Type 2 Diabetes Over a 7-Year Follow-up Period: The CODAM Study. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 1900–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alic, L.; Dendinovic, K.; Papac-Milicevic, N. The Complement System in Lipid-Mediated Pathologies. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1511886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaye, S.; Lokki, A.I.; Hanttu, A.; Nissilä, E.; Heinonen, S.; Hakkarainen, A.; Lundbom, J.; Lundbom, N.; Saarinen, L.; Tynninen, O.; et al. Upregulation of Early and Downregulation of Terminal Pathway Complement Genes in Subcutaneous Adipose Tissue and Adipocytes in Acquired Obesity. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, B.; Hamad, O.A.; Ahlström, H.; Kullberg, J.; Johansson, L.; Lindhagen, L.; Haenni, A.; Ekdahl, K.N.; Lind, L. C3 and C4 Are Strongly Related to Adipose Tissue Variables and Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 44, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, K.; Begum, R.; Yang, C.; Wang, H. Complement Activation in Obesity, Insulin Resistance, and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. World J. Diabetes 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebekhtiari, N.; Saraswat, M.; Joenväärä, S.; Jokinen, R.; Lovric, A.; Kaye, S.; Mardinoglu, A.; Rissanen, A.; Kaprio, J.; Renkonen, R.; et al. Plasma Proteomics Analysis Reveals Dysregulation of Complement Proteins and Inflammation in Acquired Obesity—A Study on Rare BMI-Discordant Monozygotic Twin Pairs. Proteom.–Clin. Appl. 2019, 13, 1800173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, K.; He, S.; Li, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Yu, K.; Long, P.; Wang, J.; Diao, T.; et al. Association of Complement C3 With Incident Type 2 Diabetes and the Mediating Role of BMI: A 10-Year Follow-Up Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2023, 108, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, T.; Itoh, Y.; Yamashita, S.; Koide, K.; Harada, N.; Yano, Y.; Ikeda, N.; Azuma, K.; Atsumi, Y. Clinical Significance of Serum Complement Factor 3 in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 127, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunturiz Albarracín, M.L.; Forero Torres, A.Y. Adiponectin and Leptin Adipocytokines in Metabolic Syndrome: What Is Its Importance? Dubai Diabetes Endocrinol. J. 2020, 26, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaratnam, R.; Skov, V.; Paulsen, S.K.; Juhl, S.; Kruse, R.; Hansen, T.; Halkier, C.; Kristensen, J.M.; Vind, B.F.; Richelsen, B.; et al. A Signature of Exaggerated Adipose Tissue Dysfunction in Type 2 Diabetes Is Linked to Low Plasma Adiponectin and Increased Transcriptional Activation of Proteasomal Degradation in Muscle. Cells 2022, 11, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arderiu, G.; Mendieta, G.; Gallinat, A.; Lambert, C.; Díez-Caballero, A.; Ballesta, C.; Badimon, L. Type 2 Diabetes in Obesity: A Systems Biology Study on Serum and Adipose Tissue Proteomic Profiles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, D.; Li, G.; Jiang, C.; Hu, J.; Hu, X. Regulatory Mechanisms of Macrophage Polarization in Adipose Tissue. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1149366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogilenko, D.A.; Danko, K.; Larionova, E.E.; Shavva, V.S.; Kudriavtsev, I.V.; Nekrasova, E.V.; Burnusuz, A.V.; Gorbunov, N.P.; Trofimov, A.V.; Zhakhov, A.V.; et al. Differentiation of Human Macrophages with Anaphylatoxin C3a Impairs Alternative M2 Polarization and Decreases Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Cytokine Secretion. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2022, 100, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponczek, M.B. High Molecular Weight Kininogen: A Review of the Structural Literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branquinho, J.; Neves, R.L.; Bader, M.; Pesquero, J.B. Bradykinin Receptors in Metabolic Disorders: A Comprehensive Review. Drugs Drug Candidates 2025, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feener, E.P.; Zhou, Q.; Fickweiler, W. Role of Plasma Kallikrein in Diabetes and Metabolism. Thromb. Haemost. 2013, 110, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheema, A.K.; Kaur, P.; Fadel, A.; Younes, N.; Zirie, M.; Rizk, N.M. Integrated Datasets of Proteomic and Metabolomic Biomarkers to Predict Its Impacts on Comorbidities of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2020, 13, 2409–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carruthers, N.J.; Strieder-Barboza, C.; Caruso, J.A.; Flesher, C.G.; Baker, N.A.; Kerk, S.A.; Ky, A.; Ehlers, A.P.; Varban, O.A.; Lyssiotis, C.A.; et al. The Human Type 2 Diabetes-Specific Visceral Adipose Tissue Proteome and Transcriptome in Obesity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altalhi, R.; Pechlivani, N.; Ajjan, R.A. PAI-1 in Diabetes: Pathophysiology and Role as a Therapeutic Target. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; McCulloh, R.J. Hemopexin and Haptoglobin: Allies against Heme Toxicity from Hemoglobin Not Contenders. Front. Physiol. 2015, 6, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montecinos, L.; Eskew, J.D.; Smith, A. What Is Next in This “Age” of Heme-Driven Pathology and Protection by Hemopexin? An Update and Links with Iron. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabuza, K.B.; Sibuyi, N.R.S.; Mobo, M.P.; Madiehe, A.M. Differentially Expressed Serum Proteins from Obese Wistar Rats as a Risk Factor for Obesity-Induced Diseases. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, H.A.; Zayed, M.; Wayhart, J.P.; Fabbrini, E.; Love-Gregory, L.; Klein, S.; Semenkovich, C.F. Physiologic and Genetic Evidence Links Hemopexin to Triglycerides in Mice and Humans. Int. J. Obes. 2017, 41, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, S.; Chen, Y. Comparison of Plasma Exosome Proteomes Between Obese and Non-Obese Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2023, 16, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauwen, S.; Bakker, B.; de Jong, E.K.; Fauser, S.; Hoyng, C.B.; Lefeber, D.J.; den Hollander, A.I. Analysis of Hemopexin Plasma Levels in Patients with Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Mol. Vis. 2022, 28, 536–543. [Google Scholar]

- Hazegh, K.; Fang, F.; Bravo, M.D.; Tran, J.Q.; Muench, M.O.; Jackman, R.P.; Roubinian, N.; Bertolone, L.; D’Alessandro, A.; Dumont, L.; et al. Blood Donor Obesity Is Associated with Changes in Red Blood Cell Metabolism and Susceptibility to Hemolysis in Cold Storage and in Response to Osmotic and Oxidative Stress. Transfusion 2021, 61, 435–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merle, N.S.; Grunenwald, A.; Figueres, M.-L.; Chauvet, S.; Daugan, M.; Knockaert, S.; Robe-Rybkine, T.; Noe, R.; May, O.; Frimat, M.; et al. Characterization of Renal Injury and Inflammation in an Experimental Model of Intravascular Hemolysis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merle, N.S.; Grunenwald, A.; Rajaratnam, H.; Gnemmi, V.; Frimat, M.; Figueres, M.-L.; Knockaert, S.; Bouzekri, S.; Charue, D.; Noe, R.; et al. Intravascular Hemolysis Activates Complement via Cell-Free Heme and Heme-Loaded Microvesicles. JCI Insight 2018, 3, e96910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balla, J.; Zarjou, A. Heme Burden and Ensuing Mechanisms That Protect the Kidney: Insights from Bench and Bedside. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnagarin, R.; Dharmarajan, A.M.; Dass, C.R. PEDF-Induced Alteration of Metabolism Leading to Insulin Resistance. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 401, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, P.E.; Wewer Albrechtsen, N.J.; Tyanova, S.; Grassl, N.; Iepsen, E.W.; Lundgren, J.; Madsbad, S.; Holst, J.J.; Torekov, S.S.; Mann, M. Proteomics Reveals the Effects of Sustained Weight Loss on the Human Plasma Proteome. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2016, 12, 901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachim, H.A.; Iqbal, Z.; Gibson, J.M.; Baricevic-Jones, I.; Campbell, A.E.; Geary, B.; Syed, A.A.; Whetton, A.; Soran, H.; Donn, R.P.; et al. Relationship between the Plasma Proteome and Changes in Inflammatory Markers after Bariatric Surgery. Cells 2021, 10, 2798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenab, A.; Roghanian, R.; Emtiazi, G. Bacterial Natural Compounds with Anti-Inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Properties (Mini Review). Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 3787–3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Zheng, J.; Chen, L.; You, S.; Huang, H. Role of Apolipoproteins in the Pathogenesis of Obesity. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 545, 117359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Barba, M.; Muñoz Garcia, A.; de Winter, T.J.J.; de Graaf, N.; van Agen, M.; van der Sar, E.; Lambregtse, F.; Daleman, L.; van der Slik, A.; Zaldumbide, A.; et al. Apolipoprotein L Genes Are Novel Mediators of Inflammation in Beta Cells. Diabetologia 2024, 67, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Maita, D.; Thundivalappil, S.R.; Riley, F.E.; Hambsch, J.; Van Marter, L.J.; Christou, H.A.; Berra, L.; Fagan, S.; Christiani, D.C.; et al. Hemopexin in Severe Inflammation and Infection: Mouse Models and Human Diseases. Crit. Care 2015, 19, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frances, L.; Tavernier, G.; Viguerie, N. Adipose-Derived Lipid-Binding Proteins: The Good, the Bad and the Metabolic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandooren, J.; Itoh, Y. Alpha-2-Macroglobulin in Inflammation, Immunity and Infections. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 803244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgo, C.; D’Amore, C.; Sarno, S.; Salvi, M.; Ruzzene, M. Protein Kinase CK2: A Potential Therapeutic Target for Diverse Human Diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgo, C.; Milan, G.; Favaretto, F.; Stasi, F.; Fabris, R.; Salizzato, V.; Cesaro, L.; Belligoli, A.; Sanna, M.; Foletto, M.; et al. CK2 Modulates Adipocyte Insulin-Signaling and Is up-Regulated in Human Obesity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 17569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, Y.-C.; Wang, Y.-H.; Chen, H.-H.; Lo, S.-F.; Chen, S.-Y.; Tsai, F.-J. Effects of Casein Kinase 2 Alpha 1 Gene Expression on Mice Liver Susceptible to Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Obesity. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 17, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roher, N.; Miró, F.; José, M.; Trujillo, R.; Plana, M.; Itarte, E. Protein Kinase CK2 Is Altered in Insulin-resistant Genetically Obese (Fa/Fa) Rats. FEBS Lett. 1998, 437, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, L.R.; Komander, D.; Alessi, D.R. The Nuts and Bolts of AGC Protein Kinases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Zhang, L.; Biswas, S.; Schugar, R.C.; Brown, J.M.; Byzova, T.; Podrez, E. Akt3 Inhibits Adipogenesis and Protects from Diet-Induced Obesity via WNK1/SGK1 Signaling. JCI Insight 2017, 2, e95687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, N.K.; Mehta, K.D. Protein Kinase C-Beta: An Emerging Connection between Nutrient Excess and Obesity. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2014, 1841, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gorp, P.R.R.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Tsonaka, R.; Mei, H.; Dekker, S.O.; Bart, C.I.; De Coster, T.; Post, H.; Heck, A.J.R.; et al. Sbk2, a Newly Discovered Atrium-Enriched Regulator of Sarcomere Integrity. Circ. Res. 2022, 131, 24–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, P.; Bi, X.; Ng, C.F.; Tse, M.C.L.; Hang, M.; Pang, B.P.S.; Iu, E.C.Y.; Chan, W.S.; Ooi, X.C.; Sun, A.; et al. Src Homology 3 Domain Binding Kinase 1 Protects against Hepatic Steatosis and Insulin Resistance through the Nur77–FGF21 Pathway. Hepatology 2023, 77, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kannan, N.; Neuwald, A.F. Evolutionary Constraints Associated with Functional Specificity of the CMGC Protein Kinases MAPK, CDK, GSK, SRPK, DYRK, and CK2α. Protein Sci. 2004, 13, 2059–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Seyoum, B.; Msallaty, Z.; Mallisho, A.; Caruso, M.; Damacharla, D.; Ma, D.; Al-janabi, W.; Tagett, R.; et al. Kinome Profiling Reveals Abnormal Activity of Kinases in Skeletal Muscle from Adults With Obesity and Insulin Resistance. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, 644–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, M.; Matesanz, N.; Pulgarín-Alfaro, M.; Nikolic, I.; Sabio, G. Uncovering the Role of P38 Family Members in Adipose Tissue Physiology. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 572089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazakerley, D.J.; van Gerwen, J.; Cooke, K.C.; Duan, X.; Needham, E.J.; Díaz-Vegas, A.; Madsen, S.; Norris, D.M.; Shun-Shion, A.S.; Krycer, J.R.; et al. Phosphoproteomics Reveals Rewiring of the Insulin Signaling Network and Multi-Nodal Defects in Insulin Resistance. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshahrani, A.; Aljada, A.; Masood, A.; Mujammami, M.; Alfadda, A.A.; Musambil, M.; Alanazi, I.O.; Al Dubayee, M.; Abdel Rahman, A.M.; Benabdelkamel, H. Proteomic Profiling Identifies Distinct Regulation of Proteins in Obese Diabetic Patients Treated with Metformin. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.-T.; Xiong, Y.-M.; Zhu, H.-D.; Shi, X.-L.; Yu, B.; Ding, H.-G.; Xu, R.-J.; Ding, J.-L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, J. Proteomics and Bioinformatics Analysis of Cardiovascular Related Proteins in Offspring Exposed to Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 1021112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coverley, J.A.; Baxter, R.C. Phosphorylation of Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Proteins. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 1997, 128, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries-van der Weij, J.; de Haan, W.; Hu, L.; Kuif, M.; Oei, H.L.D.W.; van der Hoorn, J.W.A.; Havekes, L.M.; Princen, H.M.G.; Romijn, J.A.; Smit, J.W.A.; et al. Bexarotene Induces Dyslipidemia by Increased Very Low-Density Lipoprotein Production and Cholesteryl Ester Transfer Protein-Mediated Reduction of High-Density Lipoprotein. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 2368–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Royce, D.B.; Risingsong, R.; Williams, C.R.; Sporn, M.B.; Liby, K.T. The Rexinoids LG100268 and LG101506 Inhibit Inflammation and Suppress Lung Carcinogenesis in A/J Mice. Cancer Prev. Res. 2016, 9, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, J.W.; Hong, J.; Mills, S.A.; Lawn, R.M. The LXR Ligand T0901317 Induces Severe Lipogenesis in the Db/Db Diabetic Mouse. J. Lipid Res. 2003, 44, 2039–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamori, T.; Inanami, O.; Nagahata, H.; Cui, Y.-D.; Kuwabara, M. Roles of P38 MAPK, PKC and PI3-K in the Signaling Pathways of NADPH Oxidase Activation and Phagocytosis in Bovine Polymorphonuclear Leukocytes. FEBS Lett. 2000, 467, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontayne, A.; My-Chan Dang, P.; Gougerot-Pocidalo, M.-A.; El Benna, J. Phosphorylation of P47phox Sites by PKC α, βΙΙ, δ, and ζ: Effect on Binding to P22phox and on NADPH Oxidase Activation. Biochemistry 2022, 41, 7743–7750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The PKC-DRS Study Group. The Effect of Ruboxistaurin on Visual Loss in Patients with Moderately Severe to Very Severe Nonproliferative Diabetic Retinopathy: Initial Results of the Protein Kinase C β Inhibitor Diabetic Retinopathy Study (PKC-DRS) Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Diabetes 2005, 54, 2188–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Yong, W.; Zhu, J.; Shi, D. DPP4 Regulates DHCR24-Mediated Cholesterol Biosynthesis to Promote Methotrexate Resistance in Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplastic Cells. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 704024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagami, H.; Morishita, R.; Yamamoto, K.; Yoshimura, S.; Taniyama, Y.; Aoki, M.; Matsubara, H.; Kim, S.; Kaneda, Y.; Ogihara, T. Phosphorylation of P38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Downstream of Bax-Caspase-3 Pathway Leads to Cell Death Induced by High d-Glucose in Human Endothelial Cells. Diabetes 2001, 50, 1472–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newby, L.K.; Marber, M.S.; Melloni, C.; Sarov-Blat, L.; Aberle, L.H.; Aylward, P.E.; Cai, G.; de Winter, R.J.; Hamm, C.W.; Heitner, J.F.; et al. Losmapimod, a Novel P38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Inhibitor, in Non-ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Randomised Phase 2 Trial. Lancet 2014, 384, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roychowdhury, T.; McNutt, S.W.; Pasala, C.; Nguyen, H.T.; Thornton, D.T.; Sharma, S.; Botticelli, L.; Digwal, C.S.; Joshi, S.; Yang, N.; et al. Phosphorylation-Driven Epichaperome Assembly Is a Regulator of Cellular Adaptability and Proliferation. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 8912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claeys, T.; Van Den Bossche, T.; Perez-Riverol, Y.; Gevaert, K.; Vizcaíno, J.A.; Martens, L. lesSDRF Is More: Maximizing the Value of Proteomics Data through Streamlined Metadata Annotation. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Riverol, Y.; Xu, Q.-W.; Wang, R.; Uszkoreit, J.; Griss, J.; Sanchez, A.; Reisinger, F.; Csordas, A.; Ternent, T.; del-Toro, N.; et al. PRIDE Inspector Toolsuite: Moving Toward a Universal Visualization Tool for Proteomics Data Standard Formats and Quality Assessment of ProteomeXchange Datasets*. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2016, 15, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bertalan, P.M.; Nokhoijav, E.; Pap, Á.; Neagu, G.C.; Káplár, M.; Darula, Z.; Kalló, G.; Prokai, L.; Csősz, É. Comprehensive Insights into Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes from Protein Network, Canonical Pathway, Phosphorylation and Antimicrobial Peptide Signatures of Human Serum. Proteomes 2025, 13, 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes13040067

Bertalan PM, Nokhoijav E, Pap Á, Neagu GC, Káplár M, Darula Z, Kalló G, Prokai L, Csősz É. Comprehensive Insights into Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes from Protein Network, Canonical Pathway, Phosphorylation and Antimicrobial Peptide Signatures of Human Serum. Proteomes. 2025; 13(4):67. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes13040067

Chicago/Turabian StyleBertalan, Petra Magdolna, Erdenetsetseg Nokhoijav, Ádám Pap, George C. Neagu, Miklós Káplár, Zsuzsanna Darula, Gergő Kalló, Laszlo Prokai, and Éva Csősz. 2025. "Comprehensive Insights into Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes from Protein Network, Canonical Pathway, Phosphorylation and Antimicrobial Peptide Signatures of Human Serum" Proteomes 13, no. 4: 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes13040067

APA StyleBertalan, P. M., Nokhoijav, E., Pap, Á., Neagu, G. C., Káplár, M., Darula, Z., Kalló, G., Prokai, L., & Csősz, É. (2025). Comprehensive Insights into Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes from Protein Network, Canonical Pathway, Phosphorylation and Antimicrobial Peptide Signatures of Human Serum. Proteomes, 13(4), 67. https://doi.org/10.3390/proteomes13040067