2. Education History, Theories and Learning Dispositif

Learning and education is certainly a complex and contested field. In the Heracletian, Socratic

maieutic traditions, learning is a process of cognitive and sociocultural maturation [

10,

11]. Instead of providing students with a solution or finished ‘product’ or superficial scattering of platitudes in a prescribed ‘mall for the intellectually lame’ [

12] (p. 186), the Ionian tradition posed a contention (ᾰ̓πορῐᾱ) to spark fruitful community reflection, a theme reflected in Freire’s later pedagogical injunctions [

13]. Cole’s [

14] take on learning echoes the approach of Pliny or Vittorino da Feltre who prescribed

multum, non multa or deep reflection rather than superficial spread. Concerns about intellectual curiosity and depth aside, an online learning focus can neglect social and pragmatic skills. Hence, Grundy’s [

15] dual theoretical–pragmatic (praxis) program design blends procedural with teleological learning outcomes.

Given philosophical contention around learning [

16], notwithstanding strong economic incentives, it is hardly surprising that modernizing education systems proves challenging. The contested literature on teaching and learning is substantive and spans many decades if not centuries [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. For Vygotsky [

20,

24], echoing Wundt’s [

25] earlier

Völkerpsychologie, learning is a socially conditioned and evolutionary process, involving micro-genesis and iterative community collaboration to activate and enrich internal biological endowments. A complex interplay of internal and external factors such as student capabilities and motivation, socioeconomic status, community and institutional settings and teacher competence all influence student maturation.

Inter alia, considerations of Special Education and Disability Needs (SEND) should be embedded in all teacher training and beyond in continuous dialogue and reflective practice [

26].

Given sociocultural conditioning and complex dynamics, a distributed systems framework helps conceptualise learning’s constituent objects, events and multiple interactions. The

learning dispositif (LD) encapsulates a learning systems perspective. A LD reflects a specific sociocultural institutional and architectural milieu where learners, teachers and administrators interact, buffeted by technological, political and economic forces. However, for Raffnsøe [

27] (p. 62) LD,

n’est pas localisée puisqu’elle existe disséminée dans le domaine and therefore to isolate its constituents is misguided. Borrowing from Cole and Engeström [

28] (p. 8),

dispositif provides a scaffold for power plays in a distributed learning system. As in any system, sub-optimal outcomes can emerge from these interactions and the

dispositif can become a sort of Panopticon where dank gloom festers [

29]. For Bottery [

30] in dystopian university LDs, unhealthy practices include excessive VC salaries, unnecessary re-structuring, curricula shuffling, Kafkaesque bureaucracy or malicious investigations that mask malign impulses to power. In a similar but urban vein, Foucault [

31] speculated that, in pathogenic as opposed to sustainable cities [

32], intellectual ‘medicalization’ controls citizens [

31] (p. 175). Notwithstanding dismissal of Foucault and other French intellectuals by Dawkins [

33], his

dispositif illuminates institutionalised suffering, psychological distress and social degradation endured by the learning underclass. Raffnsøe [

27] (p. 47] considers it,

un appareil formé d’une série de parties agencées entre elles de telle manière qu’elles influent sur le champ d’action, [instilling]

de la discipline dans ces relations qui changent dorénavant de caractère [

27] (p. 50). For Agamben [

34] (p. 31), modern

dispositifs embroil the Internet and electronic devices, including mobile phones, which influence

les gestes, les conduites, les opinions et les discours des êtres vivants. However, for Agamben, the real danger is the plethora of gadgets spewing vacuous subjectivities,

ce qui mène à la disparition de la politique. Apart from digital surveillance and Pavlovian social conditioning, other malevolent infestations of a LD could include neo-Stalinist architecture, commodification, budget cuts or managerialism [

35]. Whatever its form, the literature suggests that a LD is the learning system within its wider nuanced cultural and political context.

In terms of context, the classical literature provides some useful educational insights. Aristotle (384–322 BC) in his

Nicomachean Ethics VI.5 suggested that true and reasoned action for human flourishing or practical wisdom (

phronesis) involves sound deliberation and ethical considerations [

36]. Modern education curricula tend to focus on theoretical or practical considerations although Social Learning Theory (SLT) notes the importance of group interactions for epistemology. SLT overcomes behaviourism’s limited external focus and incorporates advances in cognitive science that demonstrate the brain’s right amygdala as the physical locus of emotionally conditioned learning. In SLT, meaning is constructed by iterative dialogues in unique cultural and historical settings. In other words, learning is a social act, embedded in a specific cultural context [

20,

24,

37]. Whilst Chomsky [

1] considers educational socialisation a malign social control artifice that serves dominant interests, pragmatists meld behaviourist with cognitive and social constructivist learning theories [

19] to attenuate environmental deprivation [

38]. Within SLT, Social Presence (SP) and Teaching Presence (TP) foster Cognitive Presence (CP) or critical, practical inquiry. SP is a salient ‘presence’ that facilitates group cohesion and communication. It nurtures professional personal relationships to improve purposeful communication with ‘real’ people [

39]. To support for critical thinking, Garrison et al. [

40] found that, even in asynchronous computerized settings, instructors can use SP to foster CP. Pragmatically, relative to written or audio, video communication can enhance instructor SP. Precursors for open communication are mutual acquaintance and understanding of student cultural milieu and social interactions, semiotics (symbolic representations) and power relations [

39]. Whilst SP is perhaps necessary, it is not enough for the emergence of critical online discourse [

41].

In Dewey’s [

42] four-phase Practical Inquiry Model (PIM), a triggering event flags issues for further inquiry. To construct meaning, students reflect critically, explore issues and integrate them into previous knowledge. The integration phase typically requires enhanced teaching presence (TP) to shepherd learners towards resolution. Kolb’s [

21] Experiential Learning Theory (ELT) also begins his sequence of learning stages with concrete experience. Subsequent ELT phases include reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation. For Kolb, the key to learning is active involvement of students, catalysed by a concrete experience or task (icebreakers, team games, problems, discussion or practical exercises). Students then reflect on these activities or take time-out from ‘doing’ and step back to question or verbalize and discuss their experience. Activities to aid reflection include writing feedback reports for other students or completing a learning log or diary. Subsequently, during the conceptualisation stage, students draw on theory to interpret events, review textbooks or ideas. Finally, students apply their new understanding to predict or forecast. A convivial atmosphere, rather than one focused on detecting ‘mistakes’, fosters collaboration, experimentation and critical reflection. As well as in situ synchronous monitoring, at the conclusion of activities, instructors should reflect honestly on teaching practices and educational values [

43].

In the Community of Inquiry (CoI) learning framework culture, emotions, institutions and learning are inextricably linked [

44,

45]. Within CoI’s, the psychological and emotional climate is shaped by culturally conditioned practices, emotions, social interactions, interpersonal relationships and teacher-student dialogues, including online ones [

17,

20,

39,

46].

Flexible delivery by taking-up, seemingly irrelevant, conversation threads can improve student engagement. Following Felder [

47] (p. 678), ‘global learners should be given the freedom to devise their own methods of solving problems’. So, rather than prescriptive, feedback should acknowledge different learning styles and diverse cultures [

48]. CoI seems to rebut an overly-prescriptively or teaching approach, mechanically constrained by learning outcomes [

7,

49]. For Garrison, learning involves both private deliberation and shared practice with a common intellectual focus moderated by the interaction of SP, CP, and TP [

50,

51]. CoI takes a constructivist perspective on knowledge mediated in dialogue between instructors and learners. Garrison and Cleveland-Innes [

41] argue that the inter-relationship of social, cognitive, and teaching presence is required for quality interaction, promoting discourse for deep and meaningful learning. In his later work, Garrison’s [

44] blends emotions into his learning mix. Rienties and Rivers [

45] think emotions interact with SP to foster a learning climate whilst TP enhances learning feedback.

For online learning, although computers are integral, they work best in conjunction with competent instructors and a properly configured educational milieu. In this regard, King’s [

52] shift from ‘sage on the stage’ to ‘guide on the side’ is useful. Rather than didactically transmitting content, class or online synchronous time should be spent on constructing meaning, exploring contention or fostering metacognition. In King’s [

52] or Mazur’s [

53] flipped classrooms, interactive sessions concentrate on information assimilation rather than transfer. For blended learning success (LS), Cleveland-Innes and Wilton [

54] also harness insights from the Community of Inquiry (CoI) to develop their Complex Adaptive Blended Learning System (CABLS) with six interacting elements (learner, teacher, technology, content, learner and institution support).

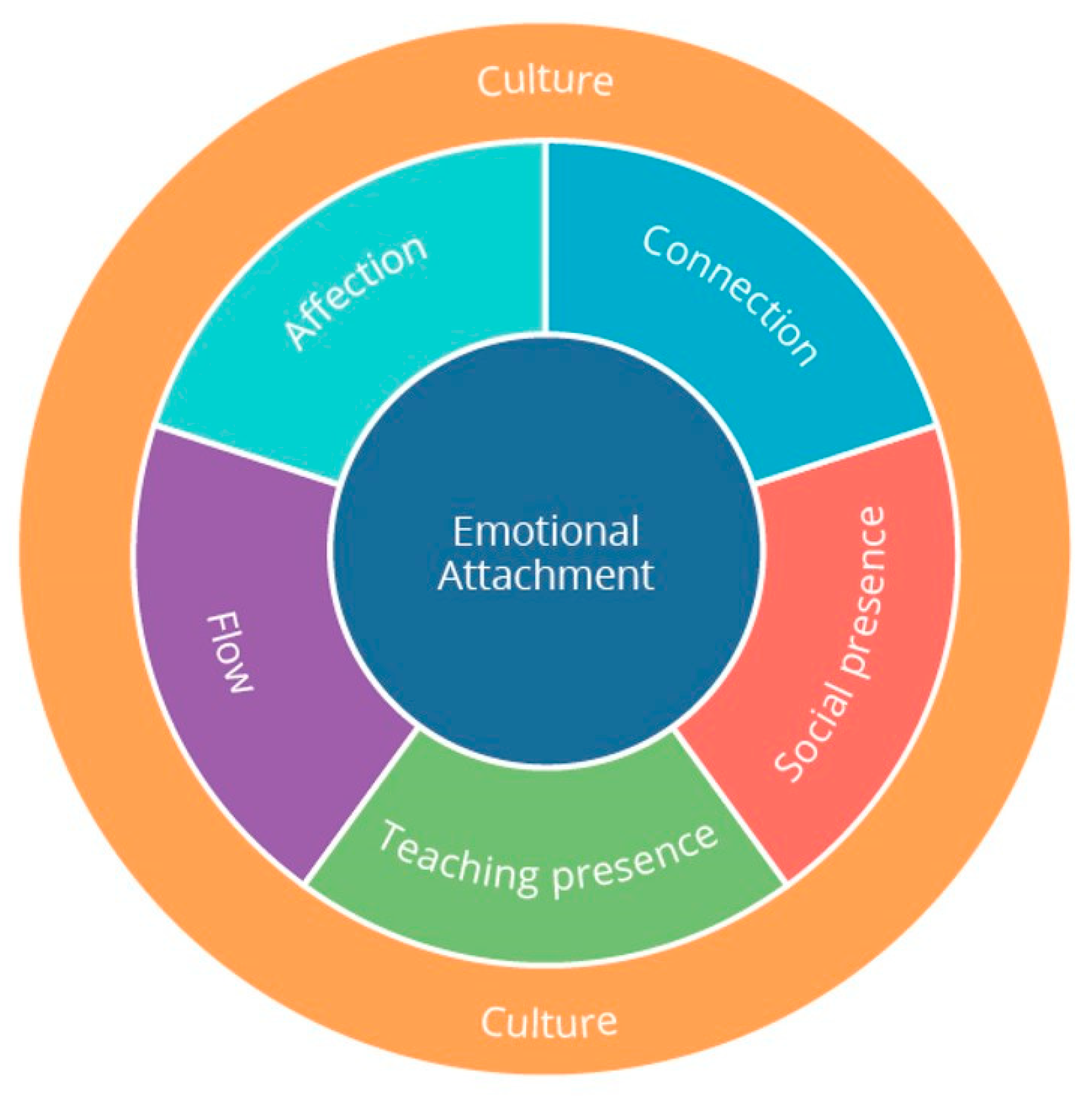

The learning literature review touched on a complex and contested field and guided the genesis of a draft EA explanatory framework. It identified the role of culture, institutions and distributed interactions in a learning dispositif. The CoI and blended learning literatures suggest that EA is just one of many influences on learning and likely moderated by SP & TP.

3. Emotional Attachment and Its Constituents

For Oxford [

55], emotions amplify other learning motives. Emotions feature prominently in child development psychology [

38,

56], marketing [

57] and organisational literatures [

58,

59]. For Oatley and Jenkins [

60], emotions condition goals and moderate communications. Some distinguish fleeting, intensive and episodic emotions from more enduring but low-intensity moods [

61]. Bechara and the Damasio [

62] showed that emotions alter brain physiology and high-level cognitive functions (reasoning, decision-making, language, reading, and mathematics). Emotional considerations thus are primordial. As opposed to emotions, emotional attachment (EA) involves an intense bond of affection with evolutionary advantages, undermined by separation. Without parental attachment, children experience anxiety, insecurity, despair and depression [

56]. Aside from parents, people attach themselves emotionally to sexual partners, places, brands, dogs, institutions, courses or teachers [

57,

63,

64,

65].

The association of attachment and emotions goes back to antiquity. At Caesar’s funeral oration in 44BC, Mark Antony famously invoked ‘attachment’ as a rhetorical device [

66]. In the organization field, Etzioni [

58] linked ‘alienative’; ‘calculative’; or, ‘moral’ emotional involvement to coercive, utilitarian or symbolic power modes. For Etzioni, relationships thrive when power mode and emotional status align. Ashforth and Humphrey [

67] call for organizations to harness emotions to improve leadership, motivation and group dynamics. In marketing, commitment and trust mediate emotional relationships of consumers to brands [

68,

69]. In 2007, Immordino-Yang and Damasio [

70] highlighted the relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Their findings indicate that when emotional, social, and moral feedback (culture) is stripped from interactions, attention, memory, decision making, motivation, social functioning and learning are all diminished.

In educational settings, connectedness means students feel they belong to a purposeful group where adults care about them and their learning. Baumeister and Leary [

71] found that the need to belong or attachment is a powerful and pervasive motivator to focus student cognitive energies on learning tasks. A sense of community and empathic concern improves effective collaboration. So rather than haranguing students, it seems more fruitful for instructors to adapt course content to fit student needs and cultural context, although flexibility has its limitations for competence.

Another EA stimulant is instructor passion and self-disclosure. Self-disclosure involves use of student names, sharing jokes or emotions and revealing personal information or facets of their life to build cohesive personal relationships with intellectual focus. More than in face-to-face classroom milieus, in cyberspace social interactions enrich learning. For online learning, early emails or upfront posts to learning platforms or passionate synchronous telephony or conference presence likely build student emotional engagement.

Aside from attachment, connection and passion, teaching presence (TP) strengthens EA. TP involves design, direction and facilitation of cognitive and social processes for educationally worthwhile discourse and meaningful learning [

72]. Instructors can enhance TP by diligent and conscientious preparation, but it also helps if they are charismatic, honest, patient and non-judgmental. EA flourishes when programs or modules are well-calibrated, scaffolded, with a variety of interesting learning activities and regular feedback [

73,

74,

75,

76]. By sustained guidance, TP helps students construct or confirm meanings and reflect for eventual metacognition.

Whether geographical, social or cultural, Moore [

77] considers ‘transactional distance’ between student and instructor an insidious pedagogical hindrance. Instructors can bridge it by programme/module structure and culturally appropriate interactions [

78]. Moore [

79] (p. 1993) and Hillman identified key ones.

Learner–learner communication

Learner–instructor communication

Learner–content engagement

Learner–computer interface interaction

Whether synchronous or asynchronous, sensitive interactions should stimulate emotions and close transactional distance.

Aside from attachment, connection, passion and TP, the literature review suggests that states of learning ‘flow’ can augment EA. For Csikszentmihalyi [

80] (p. 3), flow is, ‘when a person’s body and mind is stretched to its limits in a voluntary effort to accomplish something difficult and worthwhile’. Flow heightens concentration so students become completely absorbed in tasks. In flow, students are engaged behaviorally, cognitively and emotionally and, therefore, intrinsically motivated. Triggers for flow are well designed activities that stretch but do not frustrate students. Primers include frequent engagement, detailed ex-ante instructions and continued conversation threads rather than

ad hoc interventions or didactic diatribes [

49]. Considerate, continuous and interactive feedback can help engender self-sustaining flow for critical learning and curiosity.

Culture and specifically language-culture is another possible emotional modifier. For Ishihara and Cohen [

81] (p. 13), culture is ‘a fuzzy set of attitudes, beliefs, behavioural conventions, and basic assumptions and values that are shared by a group of people’. Interaction routines influence interpretation of meaning [

82]. However, objective culture and subjective culture need to be distinguished. Objective language culture involves institutional aspects, such as political and economic systems, art, or music and cuisine. Subjective culture involves the learned philosophical, psychological and moral beliefs, values and behaviours shared by a language community. When lexical, grammatical, semantic and these ethnographic and cultural conditioners are ignored, learning is likely depleted.

To conclude, emotions influence reasoning, decision-making, language, reading, mathematics and learning. The literature suggests that EA is a multidimensional psychological state, fostered by sustained but meaningful interactions. Passionate teachers with presence connect with students by designing relevant and delivering or absorbing lessons.

5. Methodology and Data

The research used mixed methods and a sequential explanatory approach to investigate the relative influence of LD and EA on perceived learning as well as to explore the constituents of EA itself. The research generated three questions and associated hypotheses. The first question concerned the role of LD. The second involved the influence of EA on LS. The third queried the multi-faceted constituents of EA itself (see Introduction section).

The research reviewed the main strands of EA literature in child development psychology, marketing and learning to generate a draft explanatory framework that underpinned survey questions. Although the review was not formally comprehensive, it was structured.

Figure 1 illustrates the framework constituents and factors included in the survey instrument. Likert scale questions probed student and instructor perceptions or attitudes to these aspects of EA and learning. The survey included closed-ended Likert scale questions like, ‘How would you rate the importance of the following teaching factors for emotional attachment?’ (Q8) or ‘Describe to which extent you feel emotionally attached to your class? (Q11). Students self-appraised their own learning success with 6 indicators such as, ‘On a scale of 1 (unimportant) to 7 (vital), how would you rate your classroom learning?’ (Q14) or ‘How would you rank your success in this learning? (1 = failure, 7 = outstanding) (Q17).

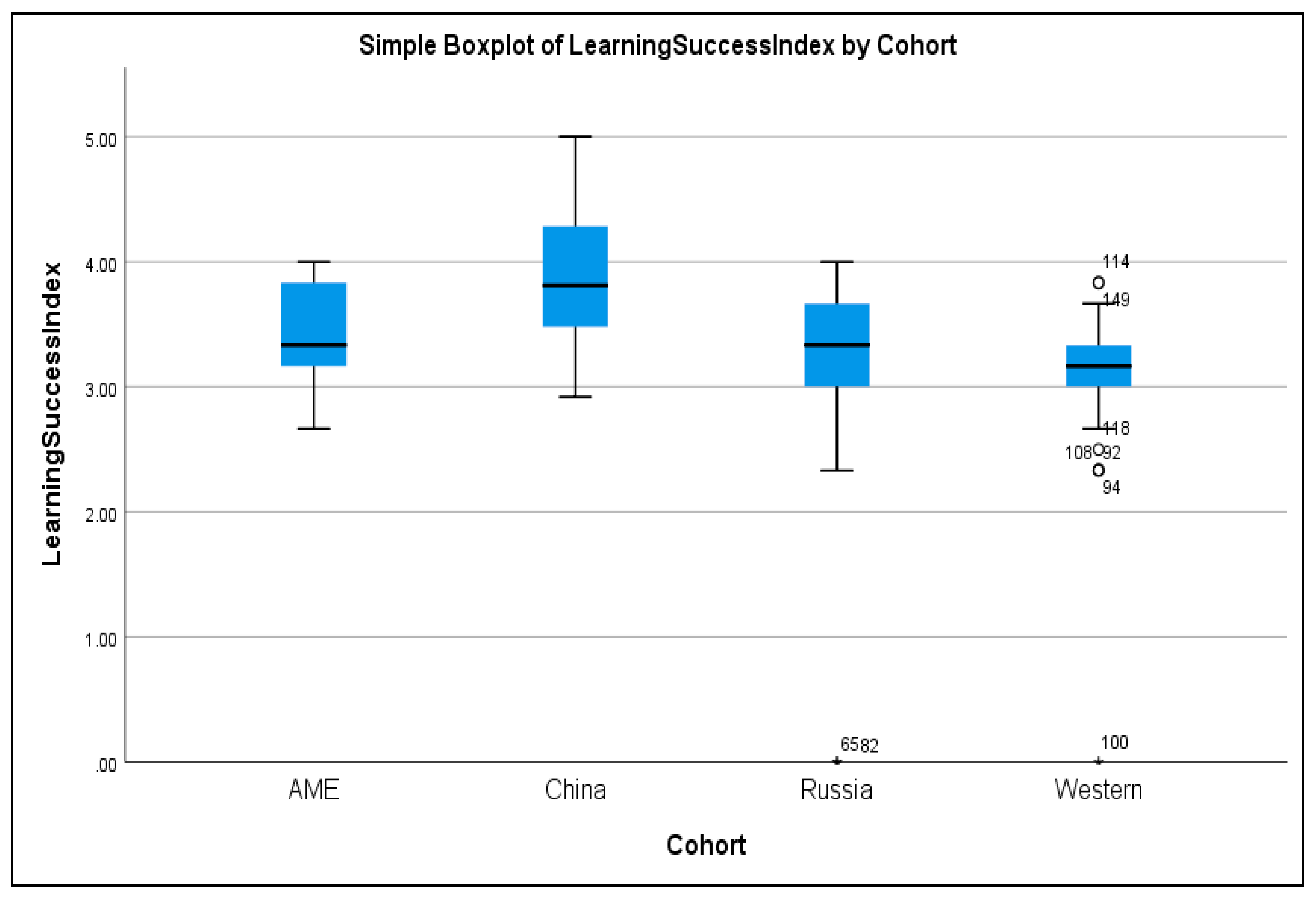

After ethical review, the research piloted the instrument on three UK academics. To identify survey respondents, the research used pragmatic, convenience sampling, distributing the instrument internationally either online (via an email link) to accessible English language and other learners or instructors. A hard copy version of the instrument was also distributed to undergraduate university students in England and China. The pragmatic convenience approach eventually generated a sample of 150 diverse learning stakeholders in Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East and China.

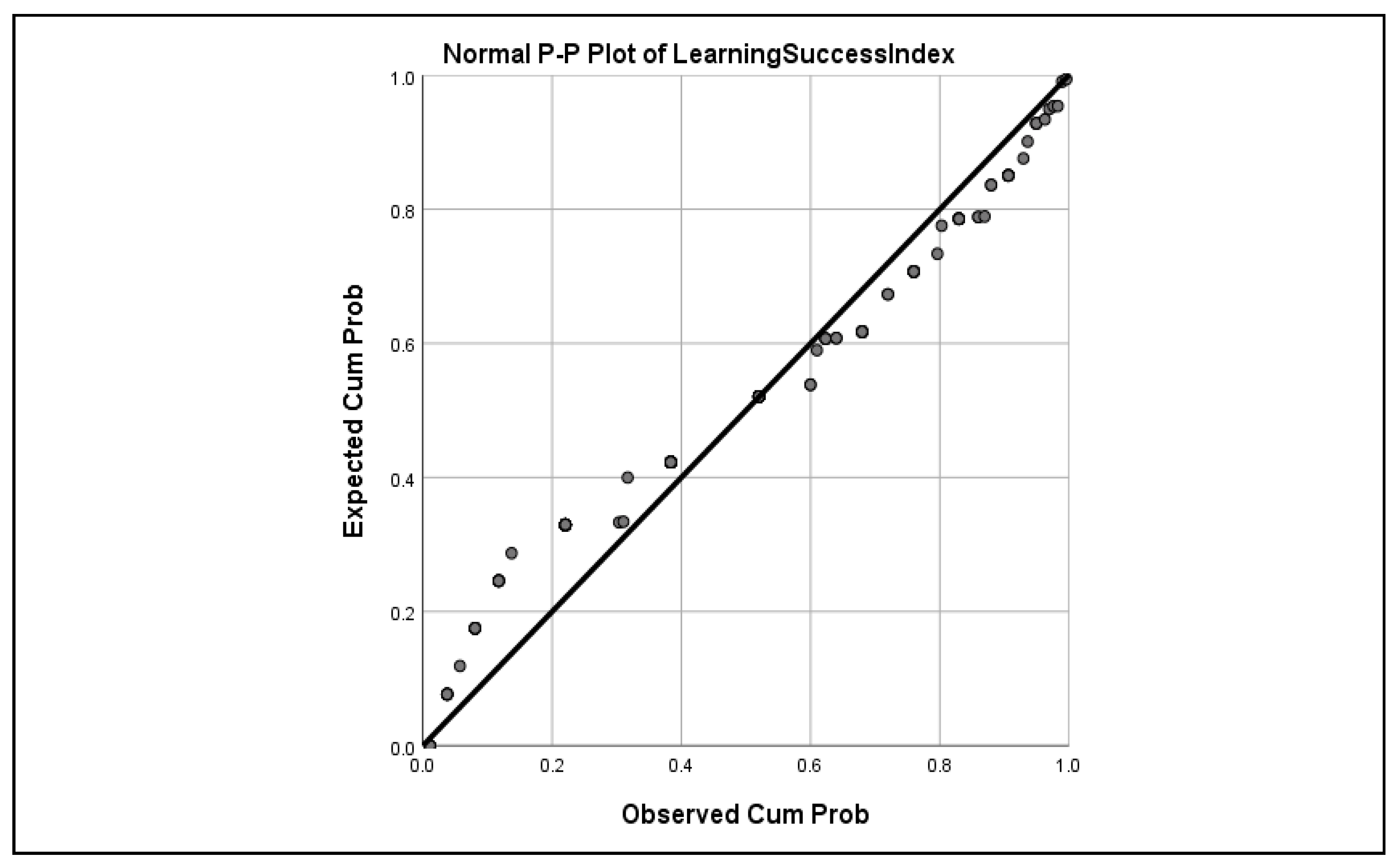

As far as we are aware, there exists no other quantitative studies on EA and learning, so it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis to investigate effects size [

83]. Although much of the questionnaire/survey data were ordinal, they were analyzed using parametric and nonparametric statistics. With adequate and reasonably normal distributions, Likert scale ordinal data can be tested parametrically [

84]. Norman [

85] suggests that parametric tests give reasonably accurate and unbiased analysis, even with skewed, autocorrelated or heteroskedastic data. The research classified 150 respondents into four cohorts on pragmatic basis, recognizing that the split was somewhat arbitrary as the groups span a wide spectrum of divergent countries and educational systems. For example, the Asia Middle East cohort amalgamated Indian and Asian students. One limitation of the study was that covariate data on average income or education levels were not included.

Subsequently, in its idiosyncratic (qualitative) phase, the study identified a convenience sample of seven academic learning experts who were interviewed face to face or online, via Skype. Interviews were conducted during the period May 2016–June 2016. Interviewees discussed their views on emotions and student learning. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed using word clouds and an adapted Framework Method [

86]. The transcriptions generated a rich diversity of individual experiences in diverse

dispositifs and with different student cohorts (see

Table 1). A range of views about EA and strategies for learning engagement and success emerged that were compared to earlier results and synthesised where possible to refine the draft EA-learning framework.

One practical challenge was that Likert scales diverged on the European and Chinese survey instruments. The research adopted proportional transformation to harmonise scales. So, for example, Chinese 7-point scores were multiplied by 5/7 to scale it down to the equivalent European instrument 5-point score. Similarly, we inflated Chinese instrument 3-point scores by 5/3. Theoretically, standardising Likert to (Z) scores assumes psychological equivalences across ordinal scales. Alternative transformations by, for example, using empirical regression coefficients assume relationships are generalizable and persist. Empirically, Colman et al. [

87] did not find dramatic improvements when adopting more complex transformation techniques.

Key variables were stated or perceived EA (IV) and LS for Learning Success dependent variable (DV). LS is a composite index, computed from six unweighted indicators (Meets Needs, Learning, Loyalty, Ideal, Success in Learning and Easy Follow). A Cronbach Alpha of 0.834 confirmed its internal reliability.