Teachers Co-Designing and Implementing Career-Related Instruction

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What are the teachers’ perceptions about the co-designed learning unit in terms of ownership and agency?

- How do the students respond to the scenario introduced at the beginning of the learning unit?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Ownership and Agency

2.2. Science Education Promoting Career Awareness

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

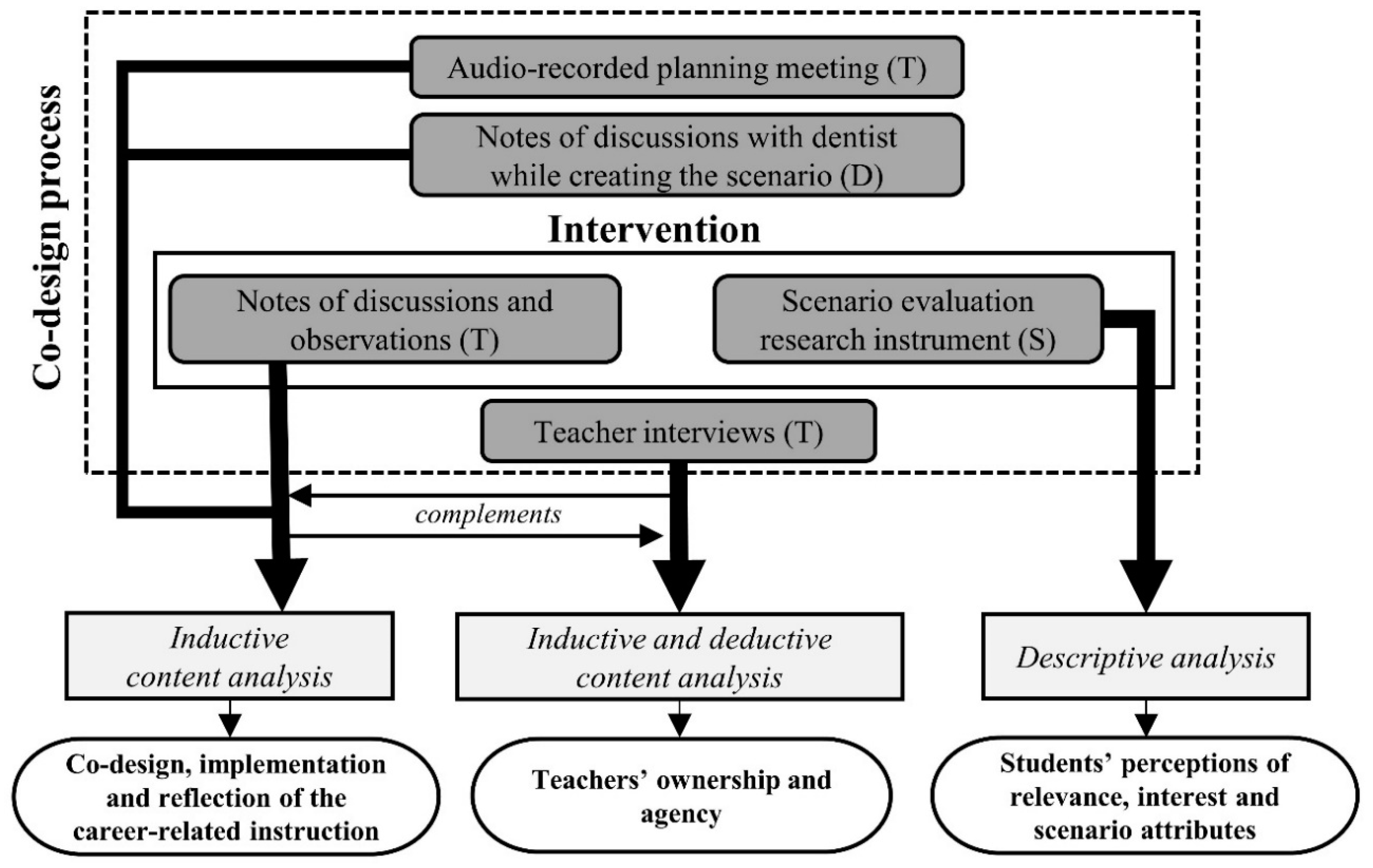

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

3.4. Validity, Reliability and Ethical Consideration

4. Results

4.1. Co-Design, Implementation and Reflection of the Career-Related Instruction

”You are not supposed to interfere too much when the students start to think about their own inquiries and activities. If they want to test something even outside your field of expertise you should just provide them the tools for that.”T1

“Something familiar and safe. If the career is totally unknown to the students, they might not learn anything from it. However, it could be interesting to give something new.”, T1; “A dentist just works with the patient, but what about everything in the background? There is technology beyond dentistry and several opportunities for development as well.”T2

4.2. Teachers’ Ownership and Agency

4.2.1. Ownership

4.2.2. Agency

4.3. Students’ Perceptions of Relevance, Interest and Scenario Attributes

5. Discussion

5.1. Further Research and Implications

5.2. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cleaves, A. The formation of science choices in secondary school. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2005, 27, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maltese, A.V.; Tai, R.H. Pipeline persistence: Examining the association of educational experiences with earned degrees in STEM among US students. Sci. Educ. 2011, 95, 877–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, A.; Kärkkäinen, S.; Keinonen, T. Career-related instruction promoting students’ career awareness and interest in science learning. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2018, 19, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avalos, B. Teacher professional development in teaching and teacher education over ten years. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 27, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonder, R.; Mamlok-Naaman, R.; Hofstein, A. Increasing science teachers ownership through the adaptation of the PARSEL modules: A “bottom-up” approach. Sci. Educ. 2008, 19, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eteläpelto, A.; Vähäsantanen, K.; Hökkä, P. How do novice teachers in Finland perceive their professional agency? Teach. Teach. 2015, 21, 660–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Driel, J.; Beijaard, D.; Verloop, N. Professional development and reform in science education: The role of teachers’ practical knowledge. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2001, 38, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogborn, J. Ownership and transformation: Teachers using curriculum innovations. Phys. Educ. 2002, 47, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M.; Biesta, G. Reinventing the Curriculum: New Trends in Curriculum Policy and Practice; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Könings, K.; Seidel, T.; van Merriënboer, J. Participatory design of learning environments: Integrating perspectives of students, teachers, and designers. Instr. Sci. 2014, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snitynsky, R.; Rose, K.; Pegg, J. Partnering teachers and scientists: Translating carbohydrate research into curriculum resources for secondary science classrooms. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, W.; Fergusson, J. Technology-enhanced science partnership initiative: Impact on secondary science teachers. Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 49, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voogt, J.; Laferrière, T.; Breuleux, A.; Itow, R.; Hickey, D.; McKenney, S. Collaborative design as a form of professional development. Instr. Sci. 2015, 43, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelaar, E.; Beijaard, D.; Boshuizen, H.; den Brok, P. Teachers’ positioning towards an educational innovation in the light of ownership, sense-making and agency. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2012, 28, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketelaar, E.; Beijaard, D.; den Brok, P.; Boshuizen, H. Teachers’ implementation of the coaching role: Do teachers’ ownership, sensemaking, and agency make a difference? Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 2013, 28, 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.; Kostova, T.; Dirks, K. Toward a theory of psychological ownership in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiting, S. Mental ownership and participation for innovation in environmental education and education for sustainable development. In Participation and Learning; Reid, A., Jensen, B., Nikel, J., Simovska, V., Eds.; Springer: Dordrech, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar, E. Teachers and Innovations: On the Role of Ownerships, Sense-Making and Agency. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universiteit Eindhoven, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Alcantara, V.; Cervantes, L.; del Razo, J.; López, R.; Perez, W. Getting to Teacher Ownership: How Schools Are Creating Meaningful Change; Annenberg Institute for School Reform, Brown University: Providence, RI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Konopasky, A.W.; Sheridan, K.M. Towards a diagnostic toolkit for the language of agency. Mind. Cult. Act. 2016, 23, 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.D.; Penuel, W.R. Studying teachers’ sensemaking to analyze teachers’ responses to professional development focused on new standards. J. Teach. Educ. 2015, 66, 136–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, J.; Greene, M. Metacognition of agency. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2007, 136, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vähäsantanen, K.; Hökkä, P.; Eteläpelto, A.; Rasku-Puttonen, H.; Littleton, K. Teachers’ professional identity negotiations in two different work organisations. Vocat. Learn. 2008, 1, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A. Recognising and realising teachers’ professional agency. Teach. Teach. 2015, 21, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, B.; Drummond, M. How teachers engage with assessment for learning: Lessons from the classroom. Res. Pap. Educ. 2006, 21, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.; Hollingsworth, H. Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2002, 18, 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Challenging Futures of Science in Society. Emerging Trends and Cutting-Edge Issues; The Masis Report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Science Education for Responsible Citizenship; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.I.; Eagly, A.H.; Linn, M.C. Women’s representation in science predicts national gender-science stereotypes: Evidence from 66 nations. J. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 107, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, A.; Hartikainen-Ahia, A.; Hense, J.; Scheersoi, A.; Keinonen, T. Secondary school students’ perceptions of working life skills in science-related careers. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2017, 39, 1339–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidou, V. Interest, attitudes and images related to science: Combining students’ voices with the voices of school science, teachers, and popular science. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2011, 6, 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- Schütte, K.; Köller, O. Discover, understand, implement, and transfer’: Effectiveness of an intervention programme to motivate students for science. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2015, 37, 2306–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, C.; Patterson, D. Teaching Strategies that Promote Science Career Awareness; Northwest Association for Biomedical Research: Seattle, WA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.nwabr.org/sites/default/files/pagefiles/science-careers-teaching-strategies-PRINT.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2019).

- Kang, J.; Keinonen, T. The effect of inquiry-based learning experiences on adolescents’ science-related career aspiration in the Finnish context. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2018, 39, 1669–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavonen, J.; Gedrovics, J.; Byman, R.; Meisalo, V.; Juuti, K.; Uitto, A. Students’ motivational orientations and career choice in science and technology: A comparative investigation in Finland and Latvia. J. Balt. Sci. Educ. 2008, 7, 86–102. [Google Scholar]

- Potvin, P.; Hasni, A. Interest, motivation and attitude towards science and technology at K-12 levels: A systematic review of 12 years of educational research. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2014, 50, 85–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, J.; Archer, L. Who aspires to a science career? A comparison of survey responses from primary and secondary school students. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2015, 13, 2170–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, P.; Hayes, S.; O’Dwyer, A. Chemistry and everyday life: Relating secondary school chemistry to the current and future lives of students. In Relevant Chemistry Education—From Theory to Practice; Eilks, I., Hofstein, A., Eds.; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Goodrum, D.; Druhan, A.; Abbs, J. The Status and Quality of Year 11 and 12 Science in Australian School; Australian Academy of Science: Canberra, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, J.; Collins, S. Pupils’ views of the role and value of the science curriculum: A focus group study. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2001, 23, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, R.; Liu, C.; Maltese, A.; Fan, X. Planning early for ‘careers in science’. Science 2006, 312, 1143–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadler, T.D. Situating socio-scientific issues in classrooms as a means of achieving goals of science education. In Socio-Scientific Issues in the Classroom. Teaching, Learning and Research; Sadler, T.D., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Falloon, G. Forging school–scientist partnerships: A case of easier said than done? J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2013, 22, 858–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellgren, J.M. Students as Scientists: A Study of Motivation in the Science Classroom. Ph.D. Thesis, Umeå Universitet, Umeå, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Peker, D.; Dolan, E. Helping students make meaning of authentic investigations: Findings from a student–teacher–scientist partnership. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2012, 7, 223–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houseal, A.K.; Abd-El-Khalick, F.; Destefano, L. Impact of a student–teacher–scientist partnership on students’ and teachers’ content knowledge, attitudes toward science, and pedagogical practices. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 2014, 51, 84–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.; Abrams, E.; Rock, B.; Spencer, S. Student/scientist partnerships: A teacher’s guide to evaluating the critical components. Am. Biol. Teach. 2001, 63, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnish National Board of Education. National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2004; Finnish National Board of Education: Helsinki, Finland, 2004.

- Finnish National Board of Education. National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2014; Finnish National Board of Education: Helsinki, Finland, 2014.

- Cigdemoglu, C.; Geban, O. Improving students’ chemical literacy levels on thermochemical and thermodynamics concepts through a context-based approach. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract. 2015, 16, 302–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rannikmae, M.; Teppo, M.; Holbrook, J. Popularity and relevance of science education literacy: Using a context-based approach. Sci. Educ. 2010, 21, 116–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bolte, C.; Streller, S.; Holbrok, J.; Rannikmae, M.; Hofstein, A.; Mamlook-Naaman, R. Introduction into the PROFILES Project and its Philosophy. In Inquiry-Based Science Education in Europe: Reflections from the PROFILES Project; Bolte, C., Holbrook, J., Rauch, F., Eds.; Freie Universität Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, J.; Rannikmae, M. Contextualisation, de-contextualisation, re-contextualisation—A science teaching approach to enhance meaningful learning for scientific literacy. In Contemporary Science Education; Eilks, I., Ralle, B., Eds.; Shaker Verlag: Aachen, Germany, 2010; pp. 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Brossard, D.; Lewenstein, B.; Bonney, R. Scientific knowledge and attitude change: The impact of a citizen science project. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2005, 27, 1099–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenney, S.; Reeves, T. Conducting Educational Design Research; Routledge: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L.; Manion, L.; Morrison, K. Research Methods in Education; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Keinonen, T.; Simon, S.; Rannikmäe, M.; Soobard, R.; Direito, I. Scenario evaluation with relevance and interest (SERI): Development and validation of a scenario measurement tool for context-based learning. Int. J. Sci. Math. Educ. 2019, 17, 1317–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotkas, T.; Holbrook, J.; Rannikmäe, M. A theory-based instrument to evaluate motivational triggers perceived by students in stem career-related scenarios. J. Balt. Sci. Educ. 2017, 16, 836–854. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckey, M.; Mamlok-Naaman, R.; Hofstein, A.; Eilks, I. The meaning of ‘relevance’ in science education and its implications for the science curriculum. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2013, 49, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, M.J.; Morse, J.M. Situating and constructing diversity in semi-structured interviews. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2015, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struckman, C.; Yammarino, F. Organizational change: A categorization scheme and response model with readiness factors. In Research in Organizational Change and Development; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2003; Volume 14, pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks, J.A.; McColskey, W. The measurement of student engagement: A comparative analysis of various methods and student self-report instruments. In Handbook of Research on Student Engagement; Christenson, S.L., Reschly, A.L., Wylie, C., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 763–782. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, L.; Ward, T.J. Expectancy-value models for the STEM persistence plans of ninth-grade, high-ability students: A comparison between Black, Hispanic, and White students. Sci. Educ. 2014, 98, 216–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmegaard, H.; Madsen, L.; Ulriksen, L. To choose or not to choose science: Constructions of desirable identities among young people considering a STEM higher education programme. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2014, 36, 186–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bybee, R.; McCrae, B. Scientific literacy and student attitudes: Perspectives from PISA 2006 science. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2011, 33, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education; PISA, OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bielaczyc, K. Informing design research: Learning from teachers’ designs of social infrastructure. J. Learn. Sci. 2013, 22, 258–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Unit Phase | Content and Aims |

|---|---|

| Lesson 1 (90 min) | |

| Scenario | Video presenting a patient visiting a dentist and asking her about carbon toothpaste. Later in the video, the dentist gives the students the following task:

|

| Inquiries |

|

| Lessons 2 and 3 (45 and 90 min) | |

| Inquiries |

|

| Career-related activities | The career presentation video was presented to the students introducing a dentist’s personal career development from high school science studies to becoming a dentist, doctor and finally to her current work specializing in plastic surgery. She was asked, e.g., about her own experiences of science studies and what motivates her in her work. |

| Lesson 4 (90 min) | |

| Bridged inquiries and career-related activities | The students filled in a laboratory form of their inquiries and created a video reporting their suggestion. The video was sent by email to the dentist. Finally, a video message from the dentist was presented thanking the students for their results and providing them accurate information about teeth whitening with hydrogen peroxide. |

| Ownership | |

| Supporting the design or ideas | Breiting [17] |

| Mental/physical effort | Struckman & Yammarino [62] |

| Identifying with the instruction | Pierce et al. [16] |

| Need for change | Ketelaar [18] |

| Agency | |

| Successes and failures | Marshall & Drummond [25] |

| Accommodation | Ketelaar et al. [14] |

| Autonomy | Allen & Penuel [21] |

| Feel of control | Konopasky & Sheridan [20]; Metcalfe & Greene [22] |

| Design Principles | Teachers | Researchers | Dentist | Students |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idea | X | X | ||

| Curriculum content | X | |||

| Socio-scientific issue | X | X | ||

| Career with shared context | X | X | ||

| Career-based scenario | ||||

| Designing the scenario | X | X | X | |

| Creating the scenario | X | X | ||

| Re-designing the scenario | X | X | ||

| Inquiries and career-related activities | ||||

| Designing scientific inquiries | X | X | ||

| Designing career-related activities | X | X | X | |

| Reflection and evaluation | X | X |

| Categories | n | Examples of Data |

|---|---|---|

| Ownership | ||

| Supporting the design or ideas | 12 | “It is good that someone else gives the tasks (to students) sometimes instead of a teacher.”, T1 |

| Mental and physical effort | 5 | “It was easy and fun just to implement something pre-made. Made my job a little easier for once”, T2 |

| Identifying with the instruction | 5 | “I have added this as one of my regularly implemented curriculum activities”, T2 |

| Need for change | 4 | “Careers are hard to include in chemistry education.”, T1; “Something old with a new twist is needed”, T2 |

| Agency | ||

| Successes and failures | 11 | “Any mistakes in the scenario or inquiries were not anyone’s fault. It happens when you create or test something new.”, T1 |

| Accommodation | 6 | “It was easy to implement and to go with the flow with the students.”, T1 “I did not see any reason not to follow the collaboratively designed learning unit.”, T2 |

| Autonomy | 4 | “I think after all, we implemented the learning unit just the way we designed and wanted.”, T2 |

| Feel of control | 3 | “The scenario was ready so late that it made me a little unsure of what was coming and how I would manage.”, T1; “After all, I did not see any reason for not following the designed learning unit. Of course, with minor changes I made along the way.”, T1 |

| Categories | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Relevance | 2.33 | 0.77 |

| Individual dimension | 2.41 | 0.76 |

| Societal dimension | 2.36 | 0.71 |

| Vocational dimension (knowledge gain) | 2.75 | 0.62 |

| Vocational dimension (future aspiration) | 1.96 | 0.72 |

| Interest | 2.27 | 0.40 |

| Scenario attributes | 2.99 | 0.41 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salonen, A.; Kärkkäinen, S.; Keinonen, T. Teachers Co-Designing and Implementing Career-Related Instruction. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040255

Salonen A, Kärkkäinen S, Keinonen T. Teachers Co-Designing and Implementing Career-Related Instruction. Education Sciences. 2019; 9(4):255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040255

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalonen, Anssi, Sirpa Kärkkäinen, and Tuula Keinonen. 2019. "Teachers Co-Designing and Implementing Career-Related Instruction" Education Sciences 9, no. 4: 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040255

APA StyleSalonen, A., Kärkkäinen, S., & Keinonen, T. (2019). Teachers Co-Designing and Implementing Career-Related Instruction. Education Sciences, 9(4), 255. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9040255