1. Introduction

I have introduced this article with testimonios from three transnational students that were forced to live in Mexico after their parents’ deportation. Although two of them are U.S. citizens, they cannot return; therefore, they live as undocumented citizens in Mexico. This trend, in which U.S.-born children are excluded from accessing basic social services due to lack of Mexican citizenship documentation, is a phenomenon that I call reverse un-documentation.

I don’t remember exactly the day that I got [to Mexico] but I remember exactly like it was yesterday. I remember that I got in my aunt’s car and she drove me all the way here and I remember the smells when I got here, I remember exactly everything. It smelled good, it smelled like tacos [laughs], and when I got here everything was different, the streets, everything, the cars, everything was different. I didn’t feel like home, I felt like crying at that same time because I thought that I wanted to be in California the rest of my life, I thought I had a future there, I thought I would have my own family there, everything. But unfortunately, when I got here the only thing that mattered to me in that right moment was to see my mom. I remember when she was in jail, I remember seeing her in that bullet proof glass, I remember that I wanted to hug my mom. You would tap on the glass and you wouldn’t be able to hear it, or you would scream as loud as you can, and you wouldn’t be able to hear it. I remember seeing her, and I said “no, forget all of that, forget my life over there in California, I want to see my mom, I want to see that person that gave me life.” So when I got there I felt like crying but I said “no, if I cry my mom is going to start crying.” So I got there and she just saw me, she started crying, she said “I missed you!” the first thing she did was hug me, she almost fell to the ground, to her knees. I picked her up and I said “no, mom, never go on your knees for me, ever, ever, ever.” I picked her up, I started crying and she said, “I missed you.” I said, “I missed you too, I missed you a lot.” At that moment, I felt like crying like a baby, like dropping to the ground and, like a kid does a tantrum but of happiness, but I said “no, I can’t cry.”.

(Paloma’s testimonio, 16 years old)

I was seven, six years old when I barely came [to Mexico.], my grandma came for us. We stayed in a garage, my aunt’s garage, for a couple months, then she told us to pack, I didn’t know what for. I didn’t ask. I just came. When I first got here I cried because I saw my mom. Yeah… I cried because I saw my mom, I had half a year without seeing her and…Yeah, that was the first time I came [to Mexico]. I didn’t really like it though, because I left a lot of friends [in the United States].

(Hans’ testimonio, 12 years old)

I remember when everything was packed, and we were driving to the border and everything, and I remember my dad said that he forgot his driver’s license and how was he going to pass through the border and everything. And I remember thinking, like, “Oh, my God, what if something happens? What if we can’t pass [to the Mexican side]? What if they get us or something?” because we were still in the U.S., I was like “what if they take us to, like, a foster home or something?” I think I was 10 or 11…. Yeah, I was scared, but I was thinking too much. I think my dad called his brother, my uncle, and they were able to come. We passed [the U.S./Mexico border], because they didn’t ask for his driver’s license, the good thing. So when we passed, I remember we got into a van and I remember seeing a lot of trees. At first it was pretty, but then it was getting ugly, like the streets and everything, the houses, and I was like “poor people” and I remember, like, you know how in the U.S. when the red light is on, there’s not people trying, like doing stuff there [referring to street vendors, including children], that’s what I remember. I was like “it’s dangerous! What if they get ran over or something!” And then I just remember like… “poor people, oh, my God, how they live here!” But now I’m used to it.

(Paula’s testimonio, 15 years old)

By law, minors who are born abroad to Mexican parent(s) are considered Mexican citizens. Technically, in order to have access to basic rights in Mexico, they must have their Clave Única de Registro de Población (CURP), which is the equivalent of a social security number. In theory, these U.S.-born transnational students are considered Mexican citizens by virtue of being the children of Mexican nationals. In reality, however, they must have a CURP in order to have access to basic rights and higher education. By not having this code, U.S.-born children of deported parents become undocumented in Mexico, experiencing the same invisibility and loss of rights that their parents experienced while living in the United States.

Of the estimated 4.1 million U.S. citizen children under age 18 that live with an undocumented parent in the United States [

1] (p. 1), approximately half a million have experienced the apprehension, detention, and deportation of at least one parent from 2011 to 2013 [

2] (p. 11). According to Gonzalez-Barrera [

3], 1 million Mexican families, along with their U.S-born children, have returned to Mexico between 2009 and 2014, with 14% of them citing deportation as the reason for their return (para. 3). Although it has not been determined how many of these children are in Mexico due to parental deportation, it is estimated that over 600,000 U.S.-born children are now attending schools in Mexico [

4] (p. 7). This return migration trend has given rise to an increased interest in post-deportation experiences [

5]. However, few researchers have focused on U.S.-born children and the challenges they face when they are forced to return to Mexico with their deported parents [

6]. Most importantly, few studies have focused on the ways in which these children navigate, make sense of their new environment, cope, and resist their oppressive realities.

This study focuses on the impact of deportation for U.S.-born transnational students as well as on the modes of resistance transnational children display. Scholars that focus on transnational students have criticized Mexican schools for viewing them from a deficit perspective [

7], ignoring their transnational funds of knowledge [

8], and considering them a burden for a Mexican educational system that does not have the resources to support them [

6,

9]. This article challenges deficit perspectives, arguing that transnational students display an array of sophisticated and complex resistance and coping mechanisms of which some scholars have no complex understanding. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to uncover the stories of three transnational youths, two of whom are U.S.-born and one of whom is Mexico-born, to convey the obstacles they face while attending schools in Mexico, and to examine their resistance mechanisms. Recognizing that the intricacy or their resistance cannot be explained by existing models, I argue that more complex modes of understanding are needed in order to understand how these children make sense of, and survive in, an unfamiliar Mexican culture and sociopolitical landscape.

To understand the experiences of transnational children forced to reside in Mexico after the deportation of their parent(s), this study asked the following research questions: (1) How are the educational experiences of transnational youth shaped by parental deportation? (2) What tools do they use to cope? and, (3) How does transnational youth enact transformative and other types of resistance?

3. Methods

This study is part of a larger research conducted from March to October 2017 in the city of Alamar, in the northern border region of Mexico, located three miles from the U.S. border. The study took place at the Grupo de Apoyo para Alumnos Migrantes (GAAM) or Support Group for Migrant Students, a government organization that is part of the State Educational System. Its main objective is the identification and record keeping of transnational students statewide in order to provide them with educational and psychological support. After learning about the organization through their website, I identified the name and contact information of the coordinator. Contact was finally established three months after an initial email, at which point, the coordinator asked for a face-to-face meeting in her office to learn more about the research. After the introductory meeting, the coordinator agreed to locate potential participants for this study. In addition, I also had a key informant from Madres por la Reunificación [Mothers for Reunification], a non-profit civil organization in Alamar founded by deported mothers who advocate for the reunification of families separated by deportation.

3.1. Participants

This study included two U.S.-born and one Mexico-born youth aged 12–17 that were forced to move to Mexico due to the deportation of their parent(s) and that attended schools in Alamar. I used

criterion sampling [

13] to identify participants. The criteria for consideration were: (1) They had to be U.S.-born youth, or Mexico-born youth who had lived in the United States for over 2/3 of their lives and had almost native-like knowledge of U.S. culture. (2) They had to be aged 9–17. (3) They had to attend Mexican schools due to the deportation of their parent(s). Participants’ demographics are described in

Table 1, below.

Participants’ profiles reveal that they lived between 9 and 12 years in the United States, which means they lived most, if not all, of their childhood in the United States. In all three cases, participants came to Mexico as a result of the deportation of their parents. They, along with their families, resettled in Alamar because they either were born there or had family in the area. At the time of this study, participants had lived between three and five years in Mexico and had attended Mexican public schools ranging from primaria (elementary) and secundaria (middle school) to preparatoria (high school).

For this research, only Paula’s family reported not having any issues enrolling her in school and having access to education immediately after their arrival in Mexico. For Paloma and Hans, it took two to three months to get them registered in school due to lack of proper Mexican documentation. The dominant language of the children at the time of their arrival in Mexico was English, and although children spoke some basic conversational Spanish, they struggled in school due to their lack of academic Spanish fluency. For this study, all three participants chose to be interviewed in English. Interestingly, they kept switching to Spanish every time they were unable to recall a word or phrase in English, which indicated to me that at the time these data were collected, they were more fluent in Spanish.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected in two phases, and participants were given the option to participate in all, some, or none of the phases. The first phase included in-depth interviews lasting between 40–60 min each. The second phase included testimonio sessions lasting from 60–90 min each. The three participants chose to participate in both phases. Since Institutional Review Board (IRB) specifications prevented me from visiting participants in their homes, data collection took place at the lobby of my hotel or at public cafes located in a popular local mall, and mothers accompanied children to all our meetings. All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, and translated by me. The purpose of the interviews was to discuss the educational experiences of participants and to contextualize those experiences in the face of parental deportation. Testimonios allowed for participants to express their thoughts and feelings more personally, to guide their own narrative, and to share what was important to them at a deeper level. The relationship built during the months that this study took place allowed for the collection of rich data that would have not been possible if the trust that developed between us had not been present.

I used MAXQDA, a software program for data analysis. I used

thematic analysis to analyze data. The purpose of thematic analysis is to identify patterns of meaning across a dataset that provide an answer to the research question being addressed [

14]. The coding system in MAXQDA was informed by the research questions and the theoretical framework. The thematic analysis produced four main categories: (1) Education-related factors, from which educational experiences were drawn; (2) forced/reverse migration factors and (3) trauma-related factors, from which impacts of deportation were drawn; and, (4) coping mechanisms, from which modes of resistance were drawn.

4. Findings

4.1. Education-Related Factors: Educational Experiences

The most significant obstacle to a smooth educational transition for transnational students, as identified by the participants, was the difference between the U.S. and Mexican educational system. Among the most cited obstacles by the students was teacher absenteeism, a teaching practice that is unfortunately common in Mexico. The students were astounded by the habit, among Mexican teachers, of simply not showing up for class without previous notice, of using class time for activities other than teaching, including checking social media on their phones, or of explaining lessons only once without checking for understanding, leaving many students confused and without the possibility of going over the lesson again. For example, Paloma shared her frustration:

Yeah, I notice that the teachers here in Mexico sometimes they don’t go to your classes and you stay like an hour without that class, like if it’s math you stay an hour without learning anything in math. Yeah. They teach you when they want to.

Yet, when students were vocal about their frustration and critiqued this incompetent teaching practice, they were silenced by their teachers. Students were reminded that the they had to get used to Mexican practices because they were no longer in the United States. Even the principals justified teachers’ inefficient practices by saying that teachers had full autonomy in their classroom and that not even the principal could interfere. When I asked Paula what she could do to improve the situation, she said: “Well, I could [talk to the teacher] but nothing will change. They would still be not doing anything because the teacher, every year, they say that he’s like that. That’s his style, not doing anything, just putting easy lessons.” This cold reception by school staff made students feel voiceless and, in some cases, it undermined their sense of agency.

4.2. Forced/Reverse Migration Factors and Trauma-Related Factors: Impacts of Deportation

The second greatest obstacle hindering transnational students’ adjustment to Mexican schools was having insensitive teachers. Surprisingly, my co-researchers did not mention academic failure when speaking about the insensitivity of their teachers, but rather, the emotional toll it took on them. Not only were teachers insensitive to the academic needs of students, refusing to offer additional assistance or to repeat instructions for those who did not master academic Spanish; worse yet, some teachers were insensitive to the special needs of the student. Hans experienced this attitude repeatedly, as described by his mother:

I have told all of them [teachers] about Hans’ ADHD. That is what he has. If you ask him something and he feels you’re going to embarrass him he would try to go off a tangent, […] or if you ask him something he will answer something else because he’s playing, but nothing else. And [teachers] tell me “but here he’s not supposed to do that, you’re used to something else,” and always, I mean, always, they bring up the subject that because “él es del otro lado” [he’s from the other side, meaning, he was born in the United States]. I tell them, “and believe me, over there [in the United States] people are more accepting than here.”

The lack of empathy towards transnational children was due to the normalization of migration in Alamar. As the GAAM coordinator explained, “We are so used to migration, that it has permeated Alamar’s social fabric to such extent that the migration of transnational students has no effect on these teachers who refuse to change their practices for them.” The coordinator often heard teachers say: “My job is to teach, my job is not to make sure that you are learning.” Therefore, the coordinator continued: “There needs to be a change not only in the teaching practices, but in the teacher’s mentality.”

The lack of Spanish proficiency was identified by all transnational students as their third biggest impediment, as it affected not only their schooling experiences, but their social interactions and emotional well-being as well. Hans’ mom explained:

His teacher scolded him all the time, she did not allow him to go to recess because he did not finish the work they had him do, that was the first day of school. She knew the situation. She knew that he did not speak Spanish well, she was well aware that he did not write absolutely any Spanish, that in order for him to write he would write letter-by-letter, letter-by-letter, and I would tell him “do what you can, m’ijo, I’m going to help you when you get here, I will help you, I will do this, I will do that,” then he would cry every day when he had to go to school.

Hans’ self-esteem was visibly damaged by this experience. It was obvious that he was cautious about speaking. Once he warmed up to me during our interactions, he shared his negative experience, which helped me understand his shyness. He shared:

[The teacher] would make fun of me ‘cause I don’t know Spanish, and he would be like “Oh, this is like that” and he laughed at me in front of everyone and embarrassed me… in front of everybody in class.

4.3. Coping Mechanisms: Modes of Resistance

Family support was the greatest coping mechanism identified by participants. For Paloma and Hans, their support came mainly from their older brother, who decided to stay behind in the United States. Paloma shared:

My brother also gives me those talks where he says: “Look at me, I stopped studying and this is how I ended up, and I don’t want you guys to end up like me too.” And honestly, well, I reflect [on] that and I say: “well… I don’t want to be like that, I want to be someone in life, I want people to know who I am and what I’m known for.”

Similarly, Hans mentioned:

My oldest brother, he would try to motivate us [when their mom was in jail], he’d say “don’t’ cry, she’s going to come one day, she’s still loves us,” and stuff like that. But my big brother, he was like a dad for us, he showed me how to skateboard, he taught me how to write in cursive, he taught me a lot of stuff.

Family encouragement was pivotal in the students’ emotional healing, but high parental involvement and advocacy also made a positive impact in the transition of the students to the Mexican educational system. Hans’ and Paloma’s mother became the president of their school and raised funds to improve the school’s lack of resources. She shared:

The school that Hans attends is right in front of where I live, we just cross the street and there it is, so, I volunteer. Then with the funds that I was able to raise, we planted trees. I started to buy fans, I started to buy water dispensers because they did not have water in the school, and then, I started to buy brooms, things for gardening, hoses, water containers, chlorine, toilet paper. Because if you would have entered the school you would have cried, because the children sometimes had to throw away their socks to use them as toilet paper. So, I would think, “I don’t want my daughter to be in this school.”

Similarly, Paula’s mother tirelessly advocated for her children; she shared:

When one speaks to the teacher, at least in my case, I went and spoke to the principal, with the teachers, with each one of them, and I explained the situation to them and it was perfect, they gave my children a lot of support.

Other coping mechanisms included coping through friendships formed in Mexico, especially with other transnational students; self-reflection to discern positive from negative behaviors; adapting to their new environment in Mexico; having a high self-esteem; being resilient; and being purposeful in their pursuit of an education.

The final coping mechanism was code switching. Children either highlighted or suppressed their transnational identity and English language in order to protect themselves from discrimination and exclusion. Paloma, Hans, and Paula avoided speaking English in public to avoid being identified as foreigners and, in some cases, being mocked or targeted. Paula explained:

Well, I wouldn’t say [I got] bullied, but sometimes [at school] they would say funny things in English but in their Spanish accent trying to make fun of me, because I used to go to school with my brother and we used to talk in English so they used to hear us and they would repeat it in Spanish trying to copy our language like that.

Despite the hardships they had to endure in Mexico, all children without exception mentioned that, with time, they learned to adapt and to be happy in Mexico. Even school seemed a little easier over time, as Hans pointed out: “I used to get only sixes and sevens [Ds and Cs], but now I’m getting eights and nines [Bs and As]. The following closing statement by Paloma sums it up: “If I could change anything about my life, honestly, I wouldn’t change anything, I’m happy with my life right now.”

5. Discussion: Resistance Modes and Evidence of Critical Consciousness

Most of the literature on transnational students ignores their funds of knowledge [

15] and agency, portraying them from a deficit-based perspective [

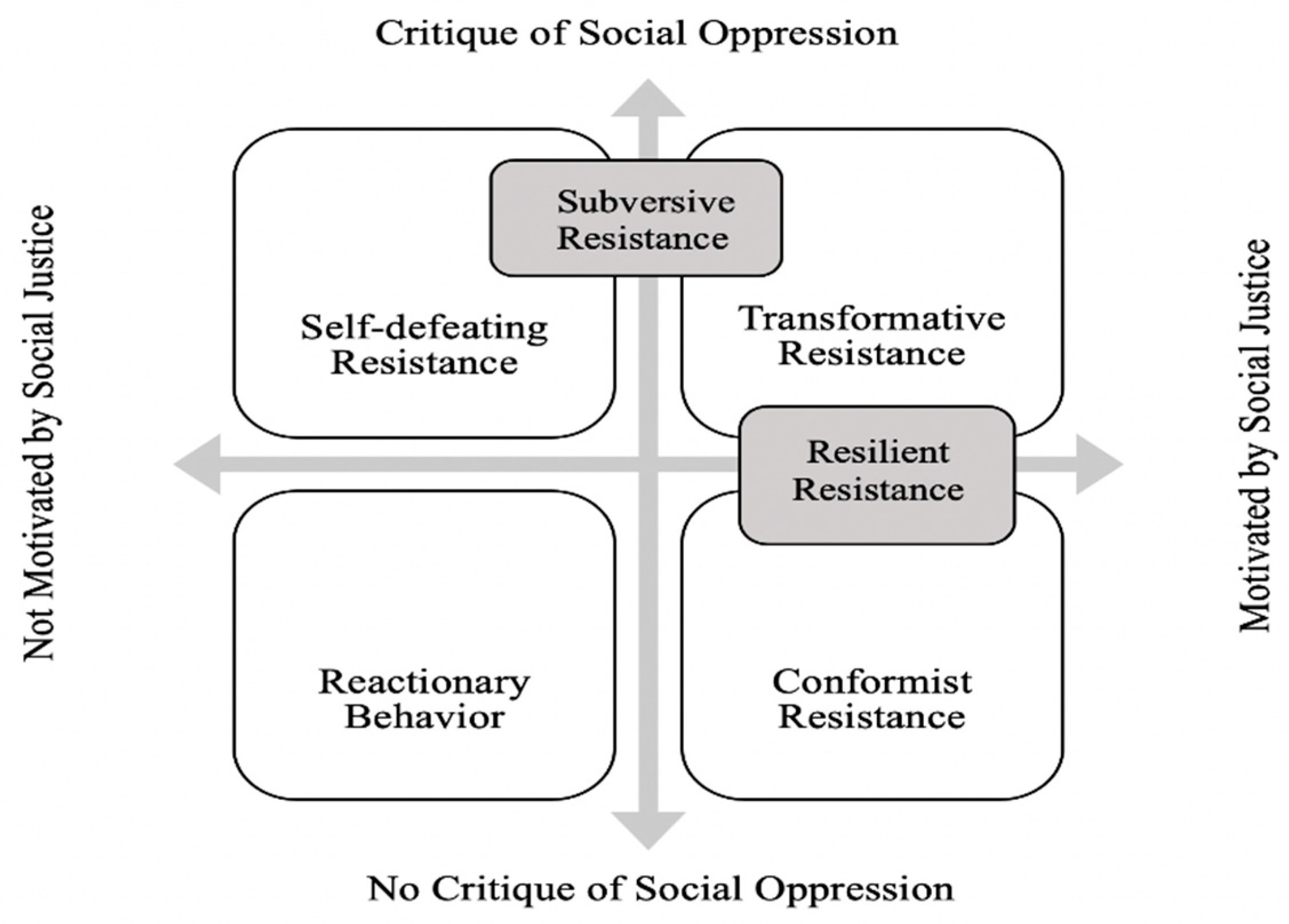

7]. Therefore, this study sought to highlight the ways in which participants resist, and by doing so, enact agency. I drew on the seminal work of Solórzano and Delgado Bernal [

10] on resistance modes, situating my participants in the self-defeating resistance and transformative resistance mode quadrants of their model. I also used Yosso’s [

11] model of resilience resistance because I found that one of my participants displayed this mode of resistance. The position of my participants within these models and relative to these modes was based on my assessment of their answers to interview questions and testimonio sessions. Below I describe the process that guided my assessment.

One of the ways in which I was able to assess their level of critical consciousness was through their engagement with, and connection of their own experiences to, the sociopolitical context. In one of our testimonio conversations, I asked my participants for their thoughts on the Mexican and U.S. governments. Paloma expressed:

I’m honestly talking about both of them. Both of them! Mexico, I’m sorry for my language but Mexico is shit, honestly, the government is shit. They have policemen here arresting innocent people when really the real criminals are out there. [Police] stop you here when really, they don’t get paid enough and they take away your money. They say, “OK if you give me this much money I’ll let you go.”

Then she went on to critique the U.S. government as well, saying:

And over there in the U.S. they, some police officers are racist, just because they see you’re African American or Hispanic they would detain you without any reason. […] They’re just being racist. That’s why I don’t like the government at all! People say “Oh, this government’s the best, if it weren’t for them we wouldn’t be here.” And I’m all, NO! [emphasis placed by participant].

Similarly, Hans shared his frustration with the U.S. government, saying:

The [U.S.] government for me, it’s like they’re making fun of us, technically, like we don’t know anything, when they say something they say it like if you don’t know about it, like if you don’t know your rights, or like if you don’t know what you have to do.

Paula’s critique was directed toward the Mexican local authorities for the lack of safety she experienced even in her own home. Paula expressed:

I still don’t feel safe because I think it was like two weeks ago, [my neighbor] started to be a drug addict and he set his own house on fire, and it was going to our house and we had to get out […] like, the police didn’t even came, like the firefighters came when my dad had already put out the fire. So, it was like, “how can we be safe?”

In addition, Paula was critical of the Mexican brand of the global sexist and misogynistic culture. In fact, she was the only female participant who would recurrently touch on this issue, as she experienced it every single day. Since she is a very soft-spoken person, she brought up the issue reluctantly at first, as evidenced by her response:

A lot of boys when a girl passes […] like if a girl passes and they do something to her, no one else would say “why are you looking at her like that?” or “why do you say something like that?” You know? When boys are inappropriate with someone or with a girl.

When I asked her directly: Has that happened to you? She laughed nervously and said: “Yeah, that has happened to me, but I try to ignore it.” Her response illustrates the she does not feel that she has the power to interrupt the gendered violence herself, and that somebody else with more social capital than her should come to her rescue. This further exemplifies her experiences of women’s disempowerment in Mexican society.

In sum, participants’ resistance was not clear-cut. They all lacked awareness of oppression at times, and they all demonstrated agency at others, making their placement in the different resistance mode quadrants reliant on both academic interpretation and analysis, as well as insider knowledge of, and cultural intuition about, Mexican culture. Accordingly, I assessed that Paloma, Hans, and Paula engaged in self-defeating, transformative, and resilient modes of resistance.

5.1. Paloma: Enacting Transformative Resistance by Questioning Teachers

Transformative resistance is nearly impossible to assess if the researcher or educator does not have a good communication with the student, a clear understanding regarding the student’s perspective, and a thorough analysis of the historical and sociopolitical contexts that formed the student’s behavior [

10]. In this study, there were ample opportunities for me to assess the sociopolitical context of my participant’s motivations through the use of interviews and testimonios, which I interpreted using my insider’s knowledge of the Mexican and American cultures, but especially, due to the relationship and trust that we built during the seven-month duration of this research, which led to a deep introspection on the part of the researcher and participants.

Based on my assessment, I placed Paloma in the transformative resistance mode quadrant because she was highly critical of systems of oppression, while at the same time showing motivation toward social justice. She was outspoken whenever she encountered oppression, and although she was motivated to work for social justice by expressing great pain when she saw the state of “her people” (referring to Mexicans) in the United States as well as in Mexico, she was not as vocal in expressing concrete steps she planned to take to work toward social justice. She resisted by being outspoken and sociopolitically conscious. She was one of the most outspoken students, especially about the lack of instruction in her school. She mentioned:

Actually, I tell my teachers, I’m like “what are you guys thinking about? What are you guys doing? ‘Cause we’re here, getting up early, coming to school, getting everything that you guys ask us, and, our parents, honestly, our parents waste all this money like on books, on notebooks, on pens, on everything you guys ask us for, and when we’re here, you just teach us what you guys want to. What’s happening?”

Despite teachers being unsympathetic and unresponsive to her critiques, Paloma shared:

[Teachers] get mad, they’re like “Oh, who are you to come up to me asking me all these questions?” [But] I’ve done it all the time. I question them all the time, like “hey! What’s going on? Are you going to teach me, or what?”

Transformative resistance is not displayed in a crystal-clear fashion in real life. For example, Paloma also displayed ambivalence about her critical consciousness. When asked who or what was responsible for her situation, she blamed herself, suggesting that no connections to structural oppression were made when it came to deportation. She shared:

I blame myself. I used to blame my mom, I’d tell her “it’s your fault that I’m here, it’s your fault that you got deported, it’s your fault!” […] In parts I think it’s my mom’s fault, because, well, because she started working in things she wasn’t supposed to. Me and my brothers, because we were so rebellious that we also got in trouble, and that’s why we’re all here, but in parts, it’s ‘cause… how can I explain it? It’s in parts that I think it is our fault but in certain times I think that it is none of our faults. I don’t know if you can understand it.

Surprisingly, although Paloma was able to connect oppression to larger sociopolitical structures in the case of her educational experiences, she was not able to make those connections when it came to her mother’s deportation. In this case, she felt it was a strictly personal failure, first on her mother’s part for making decisions that put the entire family at risk and eventually led to the family being forced to move to Mexico; and later, she expressed feeling personally responsible for her situation for being a rebellious teenager. There was no mention of structural forces such as the lack of respect for her mother’s human rights in the United States, of the detrimental effects of a patriarchal society that normalized her father’s abandonment and put all the responsibility of the children’s upbringing on their mother’s shoulders, and finally, of the institutional racism displayed by the immigration judge who was extremely harsh on her mother for not showing enough contrition and for refusing to declare herself guilty of the charges against her in order to expedite her sentencing process.

5.2. Paula: Resilient Resistance Through Discipline and Purposefulness

Yosso [

11] advanced the model developed by Solórzano and Delgado Bernal [

10] by including Freire’s critical consciousness-raising principle. Yosso extended the resistance model to include magical consciousness, or the belief that inequality is due to fate, luck, or God; naïve consciousness, or the belief that inequality is caused by ourselves, our culture, or our community; and critical consciousness, associating inequality to sociopolitical structures. In addition, individuals can be not motivated, moderately motivated, or highly motivated by social justice. Yosso developed the concept of resilient resistance as located between the conformist and transformative quadrants in concluding that students engage in behaviors that “leave the structures of domination intact, yet help the students survive and/or succeed” (p. 181). Participants in this mode of resistance used different practices to protect themselves from oppression, rather than to change it. Accordingly, I determined that Paula displayed resilient resistance because she was a high-achieving student, recognized as such in her former schools. Furthermore, she was able to survive and even succeed in her new educational environment, though her coping mechanisms did not break the systems of oppression impacting her. She resisted by being disciplined, resilient, and purposeful. For Paula, academic success helped her to cope, adapt, and shield herself from exclusion.

5.3. Hans: A Case of Self-Defeating Resistance?

As Solórzano and Delgado Bernal [

10] assert, self-defeating resistance “refers to students who may have some critique of their oppressive social conditions but are not motivated by an interest in social justice. [Their behavior] in fact helps to re-create the oppressive conditions from which it originated” (p. 317). Based on this model, I concluded that Hans displayed a self-defeating resistance because he was highly critical of oppressive systems, however, he also perpetuated the oppression by engaging in behaviors that do not work to advance social justice, but that prolong the oppression. He recognized and critiqued the systems of oppression; however, he also resisted in ways that further aggravated his oppression.

Following his older brother, Hans became negatively focused on a gang lifestyle and dress code. When asked how his life in the United States was before moving to Mexico, his response was: “Pretty messed up.” When I asked him to elaborate, he shared information about his life in the United States with his older brother, who would often act as his guide, protector, and father-figure, since his father was not present in his life. He described:

Well, with my brother, I would have to stick with him, normally I would just skate with them [brother’s gang friends]. They would rob in front of me, they would, sometimes they would smoke too. And they would always get in gang fights, I would see graffiti, they let me [do] graffiti every time too.

Hans also actively disengaged from class participation because he thought that no matter what he did, he would continue to be targeted, further alienating his relationship with teachers. During our interview, he shared:

Yeah. I always act the same. Normally I would do whatever I want because the teachers sometimes they can make fun of me, like the Biology teacher, he would make fun of me ‘cause I don’t know Spanish and he would be like “Oh, this is like that” and he laughed at me in front of everyone and embarrassed me in front of everybody in class. And they try to get a joke [meaning, they laughed at his expense].

Unfortunately, Hans’ resistance was met by a close-minded attitude from school staff who were unable and unwilling to find a positive way to engage him, causing both sides to continually disaffect each other to the point that his mother started receiving complaints about his behavior. His mother stated:

The problem now started at the secundaria [middle school], they are always calling me, that if I don’t come with him they will not let him in the school, that Hans is too arrogant, that Hans talks back to his teachers, that Hans makes fun of children when they are in class, and that… a lot of things.

What his teachers failed to recognize, was that Han’s behavior was a reaction to the relentless bullying he had been subjected to since he got to Mexico. His mother elaborated:

If they ask him something and he’s unable to pronounce it or he does not know to answer, everybody makes fun of him, and that’s how he’s been. He says: “I’d rather get a zero than to answer.” Or “I would rather this and that because the teacher always sends me to the principal’s office, or he sends me do chores [like sweeping and mopping], and everybody makes fun of me.”

In Hans’ case, he engaged in oppositional behavior, characterized by adversarial, defensive, or rebellious conduct. He resisted by disengaging from the classroom and acting up, which got him into trouble at school. Because he has been exposed to gangs most of his life, he demonstrated an obsession with their lifestyle. Although he critiqued them at times, he felt he could not escape them; he said: “Hanging out with gangs, I don’t like hanging out with them a lot, but I can’t do much because almost everyone I know or everywhere you go and try to meet, there’s gangs.” This had ramifications for him at school, especially prejudiced perceptions of him. For example, one teacher was openly prejudiced against him due to his appearance. His mother remembered: “Even the teacher says that Hans is one of the children that he sees as resembling a U.S. gang member, he said to me “because in the U.S. it’s the only thing that you see, gang members.”

5.4. Subversive Resistance: A Nepantla State between Self-Defeating and Transformative Resistance

Although Hans grew up in a toxic environment, he knew early on that being part of a gang or doing drugs was not something he wanted for his future. He shared:

My brother used to smoke weed and cigarettes and he told me to do it once, I’ve never did it, but there was one time where I was kind of curious about it. I was ten, and some friends came over and they brought a “hookah pen” which is like a little pen with smoke in it. They look like little straws and you just suck on it and smoke comes out and there’s um, cherry, I think water melon, there’s a lot of flavors. I think I did it two times then he tried to keep on bringing it and I said no because I knew I didn’t want a future like that. But then when I came here [to Mexico] I was saying “there’s not a lot of future here for anyone,” almost everyone’s on the streets, smoking weed, selling weed. Sometimes I imagine myself, if I was doing drugs, what would happen if I did drugs? A lot of people would try to find me, cops would be following me, there would be other people trying to kill me too, and I think about, so, what happens if I die too, so I get kind of scared when I think about that.

After revisiting Han’s position in the self-defeating resistance mode quadrant and after re-reading his testimonio and interview transcripts, it became evident that he was displaying a form of resistance that did not entirely fit the self-defeating model. His

“cholo” dress style and his confrontational attitude toward his teacher kept getting him into trouble at school. However, his dress code, his rejection of being mocked due to his lack of Spanish, but most importantly, his reflection about wanting a better future for himself, were signs of a type of resistance that needed to take into consideration the agency he was displaying, amid the self-defeating elements. Hans was in a

nepantla [

12,

16,

17], a border zone between self-defeating and transformative resistance. It was here that I realized that I needed to go beyond the models previously established by Solórzano and Bernal [

10]. Inspired by the work of Yosso [

11], in which she extended the resistance model to include “resilience resistance”, which stands at the border of transformative and conformist resistance, I knew I too had to find a hybrid model that stood at the borders of self-defeating and transformative resistance. The term

subversive resistance was coined during a brainstorming session at one of my writing group’s meetings; when a colleague blurted out the word “subversive” to describe Han’s behavior, the word immediately caught my attention. Meaning troublemaker, agitator, revolutionary, or dissident, subversive was the perfect word to describe Han’s resistance.

In this article,

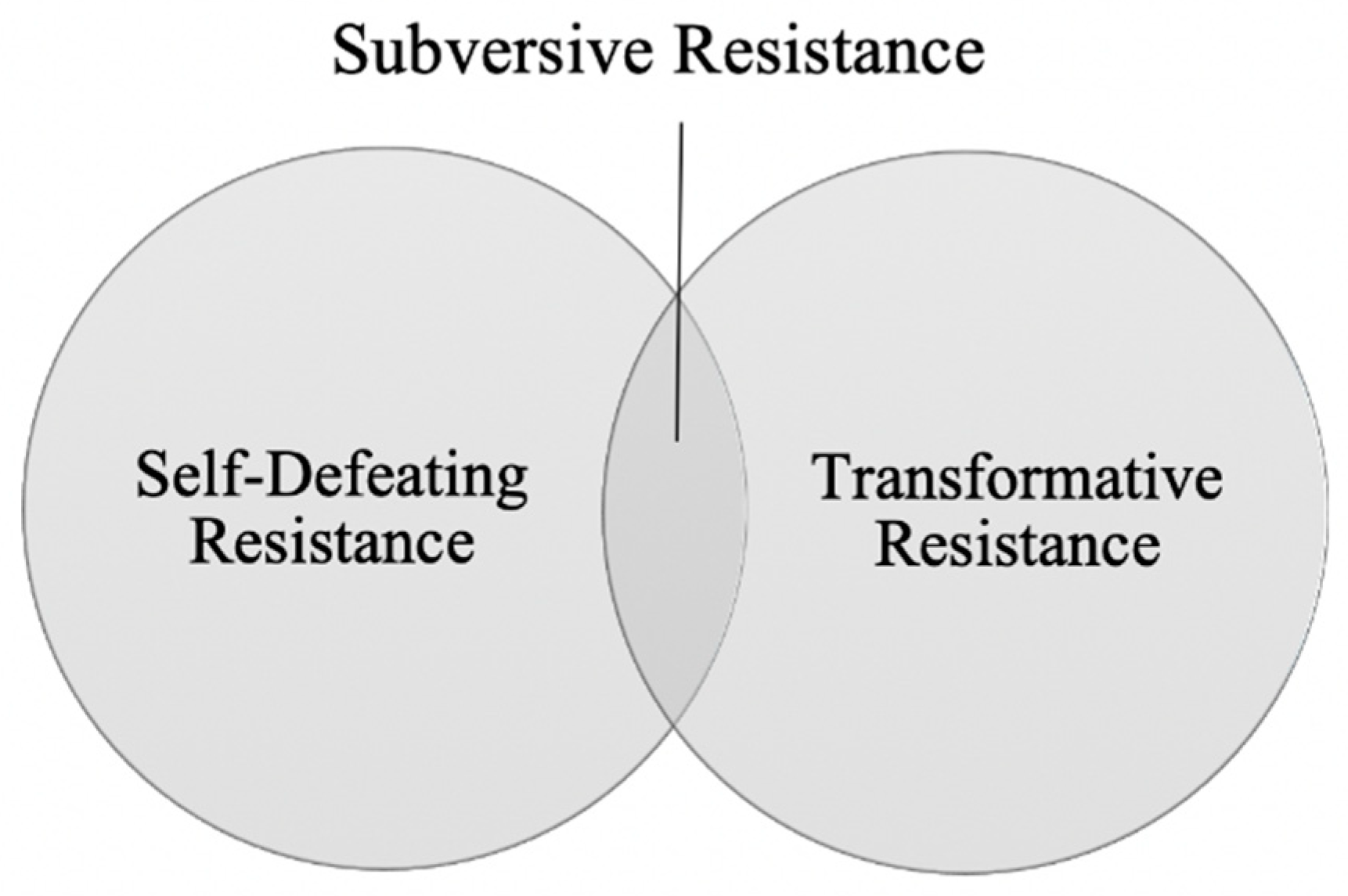

subversive resistance (see

Figure 1, below) is defined as a form of resistance situated at the border of self-defeating and transformative resistance, characterized by a behavior that at first sight seems to be self-destructive and to exacerbate oppressive conditions; however, upon deeper analysis, the behavior takes a transformative overtone as the student displays subtle manifestations of agency and social justice by refusing to be dehumanized by the oppressor or the oppressive circumstances. In Han’s case, he refused to participate in class even if that meant getting a zero, a self-defeating behavior, but he did so in order to save himself from the ridicule he was subjected to by his teacher for not speaking proper Spanish, a manifestation of transformative resistance used to counter dehumanization. In another example, according to his teacher, he used to dress and act as a “

cholo,” a behavior that was perceived as confrontational; however, belonging to a gang was the only sense of family, protection, and loyalty that he had been exposed to earlier in life. Hence, his fascination with the gang lifestyle was rooted in a sense of kinship, even though to the outside world, it was perceived as dissidence.

To understand

subversive resistance, I used the nepantla [

12,

16,

17] and Coyolxauhqui imperative [

12] concepts. Nepantla, a Nahuatl word for an in-between state, can be understood as a place of contradiction, of identity breakdowns, and buildups; a place where transformation is enacted, described as “that uncertain terrain one crosses when moving from one place to another, […] when traveling from the present identity into a new identity” [

12] (p. 56). The Coyolxauhqui imperative refers to the process of emotional and spiritual dismemberment and the art of putting the pieces back together in a new form, in a new type of “re-membering” [

12] (p. xxi). Most importantly, to Anzaldúa [

12,

16] nepantla and the Coyolxauhqui imperative represent ways to decolonize knowledge and to offer alternate ways of thinking. Both represent the border, “the locus of resistance, or rupture, of implosion and explosion, and putting together the fragments and creating a new assemblage” [

12] (p. 49).

To further my conceptualization of

subversive resistance I also consulted Sosa-Provencio’s [

18] article “Creolizing White Spaces in Teacher Education,” in which she also draws on the nepantla theories developed by Anzaldúa [

12,

16], as well as the resistance model developed by Solórzano and Delgado Bernal [

10]. In addition, Sosa-Provencio incorporated the creolization concept developed by Gordon [

19], which urges writers to decolonize disciplinary methods and to embrace an emancipatory approach. Creolization generally refers to ongoing forms of cultural convergence and ensuing culture mixing; more specifically it refers to the “illicit” blending of dominant and oppressed cultures when the people from them come into contact with one another mainly due to colonization. In these instances, “previously unconnected people whose mutual recognition was unprecedented, were thrown together in violently unequal relations [where] new perspectives, based largely in reinvention, resituating, and mistranslation began to take shape” [

19] (p. 170). As shown in

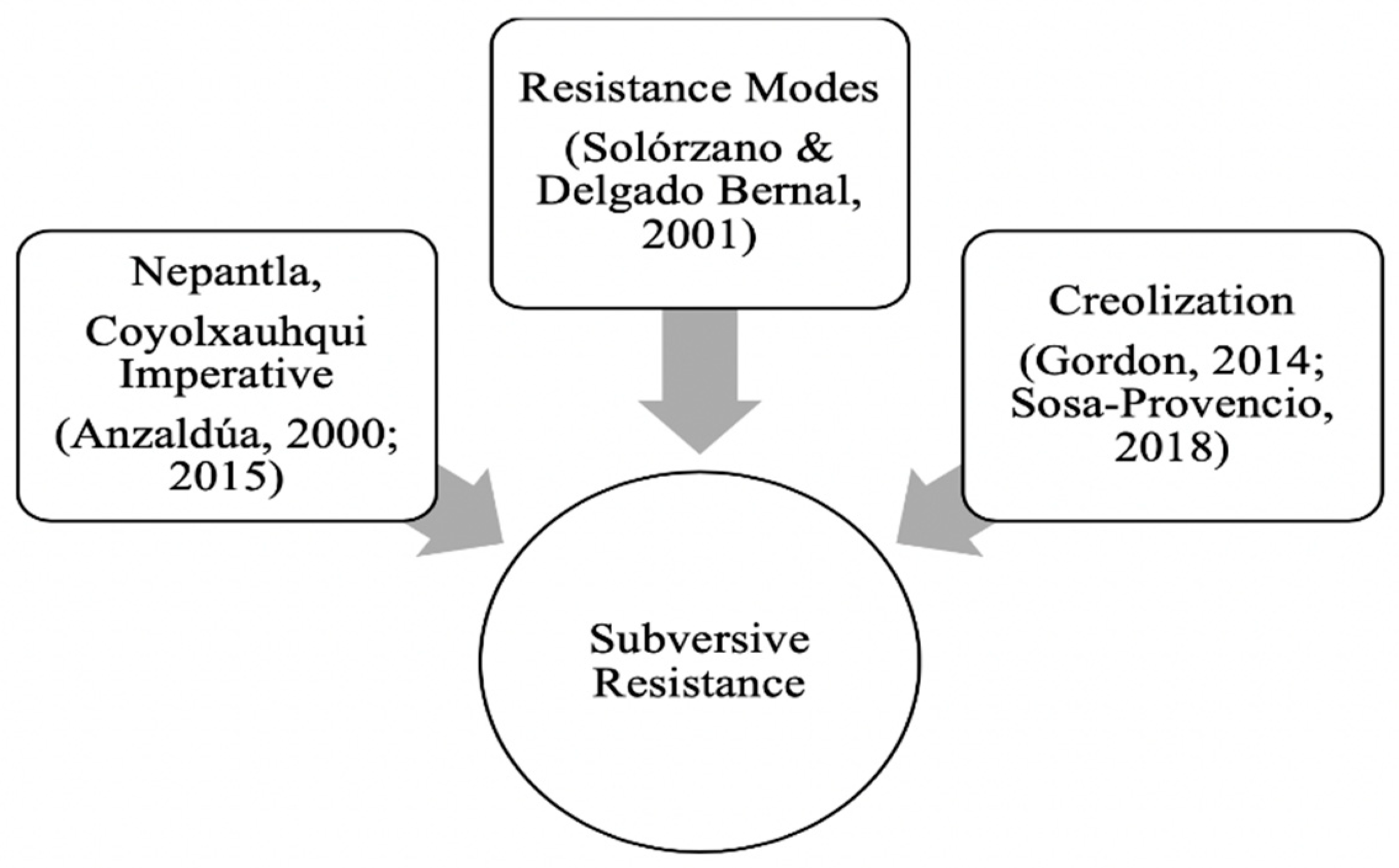

Figure 2 below, nepantla, resistance modes, and creolization conform to the theoretical foundations that support the concept of subversive resistance.

Recognizing the transformative aspects in Hans’ behavior was not immediately accomplished. In my first round of analysis, my initial reaction was to only recognize the apparent self-destructive elements in his actions, and I proceeded to place him in the self-defeating resistance without hesitation. I recognize how problematic this was on my part because my first reaction was to interpret his behavior from a deficit-based perspective. It was not until I revisited his transcripts that I started to recognize the nepantla in his actions. This prompted me to place Hans in the subversive resistance mode in-between quadrant and to reflect on who gets included in and who gets excluded from the transformative resistance mode. These questions made me reinterpret his answers and to take a closer look at the context that had prompted his reactions to the harassment to which he was subjected. I then realized that he was not only in a state of nepantla, characterized by an identity breakup and buildup, but he was also enacting a process of creolization in which he was blending, for the second time in his short life, pieces of a dominant culture, first in the United States, and later in Mexico, together with a submissive culture. On the one hand, his creolized identity as a Mexican in the United States and as an American in Mexico forced him to reinvent himself and to resituate his position blending aspects of both cultures to shield himself from equally oppressive systems; on the other hand, his creolized concept of familial bonds forced him to blend traditional notions of blood family with alternative forms of family ties that he found in the gang his brother introduced him to, which for him represented an important support system despite recognizing their unlawful conduct. See

Figure 3 below for my conceptualization of subversive resistance within the resistance model.