Abstract

This paper details a cross-cultural study of inclusive leadership practices within a basic education context in each of the following countries: Australia, Canada, and Colombia. Each school was selected after district educational leaders identified the school as being inclusive of students with diverse learning needs over an extended period of time. The researchers were particularly interested in the norms and assumptions that were evident within conversations because these were viewed as indicators of the nature of the embedded school culture within each context. School leaders and teachers were interviewed to determine the link between rhetoric and reality, and what inclusion ‘looked like’, ‘felt like’, and ‘sounded like’ at each site, and whether any discernible differences could be attributed to societal culture. A refractive phenomenological case study approach was used to capture the messages within each context and the lived experiences of the participants as they sought to cater for the needs of students. Data were collected from semi-structured interviews with school leaders and teaching staff. Each researcher conducted environmental observations, documenting the impressions and insights gained from the more implicit messages communicated verbally, non-verbally, and experientially from school structures, visuals, and school ground interactions. Themes were collated from the various narratives that were recounted. Both similarities and distinct socio-cultural differences emerged.

1. Introduction

The complexities faced by schools and school leaders continue to expand as student populations become more diverse [1]. Schools face the challenge of producing high quality educational outcomes for all students. This now includes students with special needs or disabilities, those with English as Another Language or Dialect (EALD), those who have suffered extreme trauma in their lives, and those from families facing varied difficulties. In addition, schools must cater for gender diversity, religious diversity, physical disability, and so forth. Globally, many would see UNESCO’s definition of inclusion as being the ultimate goal:

Inclusion is… a process of addressing and responding to the diversity of needs of all children, youth and adults through increasing participation in learning, cultures and communities, and reducing and eliminating exclusion within and from education. It involves changes and modifications in content, approaches, structures and strategies with a common vision that covers all children of the appropriate age range and a conviction that it is the responsibility of the regular system to educate all children [2].

The need to create inclusive learning opportunities is clear, but what is unclear is where the differences and similarities lie between country to country when it comes to the types of leadership practices that facilitate the development and maintenance of an inclusive school culture where students are catered for, irrespective of background or need.

The researchers, the authors of this paper, were particularly interested in the norms and the assumptions of each inclusive school culture, and whether school culture was influenced by society and national cultural norms, as illustrated by the ‘language-in-use’ [3] within each context. The language of school leaders and teachers provided clues as to how educational rhetoric and policy were translated into practice, and whether there might be socio-cultural differences from one school to the next. To this end, the researchers sought and gained permission to interview school leaders and teachers in an elementary school that was recognized by each education system within their locality as being an inclusive school where the seeds of acceptance, tolerance, and celebration of diversity had germinated [4]. Each researcher worked within their own country of origin (Australia, Canada, and Colombia) using collaborative conversations to unpack the essence of each school’s experiences of inclusion.

Inclusive education is an “increasingly contentious term that challenges educators and education systems” [5] (p. 528) requiring actions, strategies, convictions, and ideas. The concept of inclusive education originated in human rights principles and is apparent in international literature, legislation, policies, and documents. It is based on the key features of equity, opportunity, access, and rights, and/or on the removal of factors that exclude and marginalize [6]. The presence of these features in school organizations contributes to a culture of inclusion, connected to values, language, and dialogue [7], relationships and family interaction [8], and the nations to which people belong [9]. “Understanding an organization’s culture is to assess that which is shared by individuals within the organization, their beliefs, values, attitudes, and norms of behavior” [10] (p. 42) and how relationships are framed.

One of the most influential statements for special needs education and inclusion arose from the 1994 UNESCO conference in Salamanca, Spain. Attendees included representatives from ninety-two national government and twenty-five international educational organizations. Together, they created the Salamanca Framework for Action averring that inclusion and participation were essential to human dignity and to the enjoyment and exercise of human rights [11]. The Statement of Rights is in respect to education, as enshrined in the United Nation’s 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child. Many countries, including Australia, Canada, and Colombia, have committed to policies around: disengaged young people; people with disabilities; children at risk of disadvantage; jobless families; locational disadvantage; homelessness; people with a disability or mental illness; Indigenous student underachievement; and, new arrival and refugee vulnerabilities [12].

While the term inclusive education is common, Jahnukainen [13] raised the point that different countries may use the same educational concept differently. There may be a shared understanding about the sense of inclusion at the theoretical level, but multiple political and policy realities impact the practical operational level [14]. Regardless, the school-level picture through the eyes of the school leaders committed to establishing and maintaining inclusive education may be surprisingly similar [13].

This paper takes the stance that for schools to be truly inclusive, inclusion must be a way of thinking, a philosophy of how educators remove barriers to learning and value all members of a school community [3,6], creating a sense of belonging and a feeling of community. A key aspect of inclusion is the belief that the general education classroom should be structured to meet the needs of all the students in the class, irrespective of ability or disability. From an inclusive perspective, diversity is seen as the norm. From a socio-cultural perspective inclusion is built through shared experiences influencing practice and societal acceptance [15].

2. Materials and Methods

Taking a socio-cultural constructivist perspective, the authors acknowledge that our realities are shaped by our experiences and interactions with others [15,16]. Subconsciously, we are influenced by the culture and context in which we live. This underpins how we see our roles in community, work, and family [16,17]. The nature of learning means that leaders construct their views on leadership and enactment according to personal experiences and interactions within their socio-cultural context [17,18]. Those who work closely with leaders have their understandings of leadership that are built in a similar manner. Ultimately, it could be assumed that cultural differences will therefore influence how leaders translate rhetoric (policy) into reality (practice) within their national context. To explore lived experiences within inclusive school communities we employed a refractive phenomenological approach [19]. Refractive phenomenology is based on hermeneutic phenomenological philosophy [20,21], studying how phenomena are consciously experienced, perceived, and understood [22], then views these experiences via filters, either predetermined and/or emergent [19]. The phenomenon was the ‘inclusive school’ and the lived experiences were those of leaders and teachers, as well as documented researcher observations that were collated during time spent (6 to 8 hours in total) within each context conducting interviews and observations. Merleau-Ponty’s [22] reductive hermeneutic lenses of ‘depiction’, ‘reduction to essence’, and ‘interpretations into living knowledge’ mine the significance of these lived experiences as they pertain to the phenomenon that is under investigation [19]. Filters are applied to the data as a means of refracting researcher focus from the obvious to the less obvious, sensitizing researcher attention to a specific aspect or aspects of the overall phenomenon [19]. These filters make explicit the researcher bias that often underpins the interpretive search for an answer to a particular question, and which can otherwise remain implicit, hidden from conscious view.

The depiction stage is the initial step for the collation of an in-depth description of a lived experience, as understood by the participant who has lived it. In refractive phenomenology, each depiction is written up as a reconstructed narrative that is interspersed with wording taken directly from participant interviews and then checked with the participant and rewritten until the participant feels that this condensed experience still accurately represents their lived experience. Reduction to essence is then achieved through the coding of wording and concepts to uncover the inherent themes, or essence, of shared lived experiences [22].

Although pairs within the research team had researched together in the past, the team as a whole had not previously researched together. Realizing how important it would be to interpret data from a shared perspective a number of pre-data collection and interpretation meetings were conducted via an online platform. The researchers found they shared similar understandings in relation to key concepts underpinning the research project, such as school culture, inclusion, and the importance of lived experiences as a means of seeking a deep understanding of a phenomenon.

Researchers’ views affect how we as researcher’s frame and communicate our interpretations of the findings and their significance [23,24]. The research team acknowledged this and through collaborative development of semi-structured interview questions, constant comparisons, and sharing of insights into shared data, the authors brought their reflexive interpretations into alignment to answer the overarching question:

What socio-cultural understandings of leadership enactment, focused on establishing and maintaining an inclusive school culture, are gained from exploring the lived experiences of those working in a basic education context in each of the following countries - Australia, Canada and Colombia?

Sub-questions linked to specific filters helped answer this question:

- In what ways are shared lived experiences reflected in specific or conceptual language?

- What cultural and societal similarities and differences emerge in relation to what inclusion ‘looks like’, ‘feels like’, and ‘sounds like’ in a basic education context?

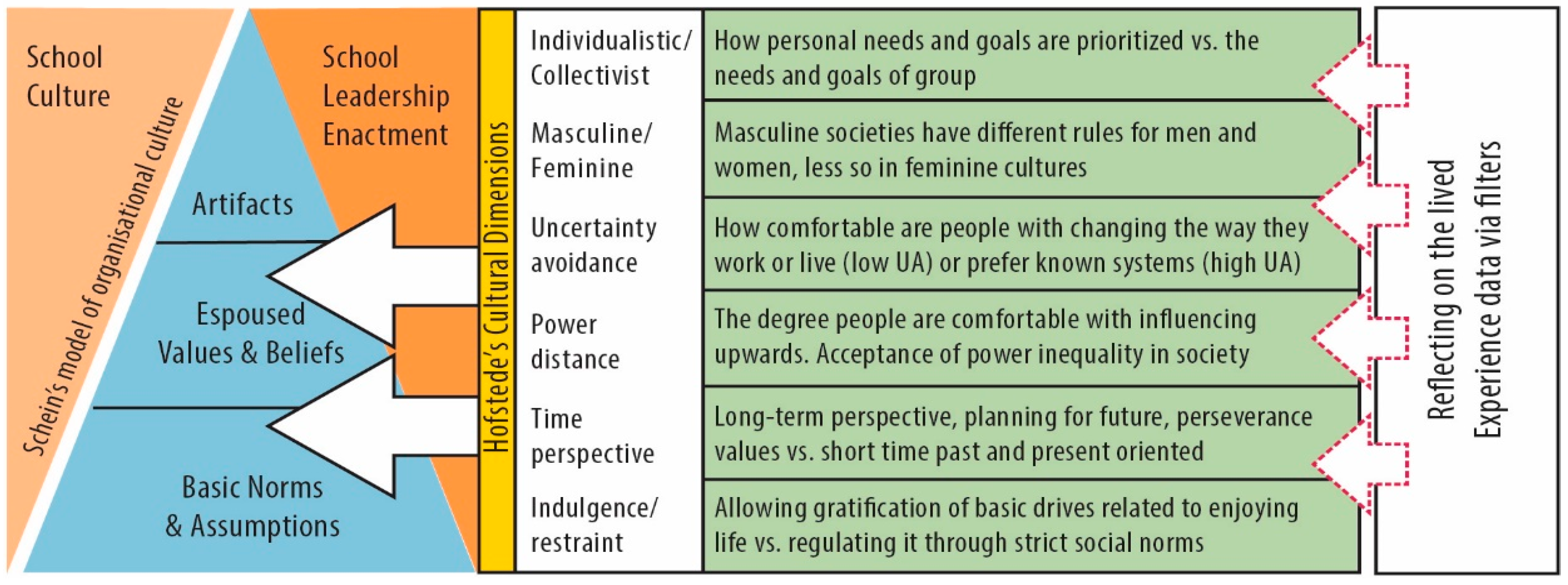

The filters applied were Schein’s Theory of Organizational Culture [7], Hofstede’s Indicators of National Cultural Differences [25], and the concept of School Leadership Enactment (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A backward mapping model of the filters applied to the data to ascertain the impact of socio-cultural context on how school leaders enact their roles and how such acts in turn impact school culture. Adapted from the work of Hofstede, Hofstede and Minkov [25], and Schein [7].

The filters for this study were pre-determined by the team in order to sensitize our attention to elements within the lived experiences that could provide insights to help us answer the overarching research question. After the reduction phase was completed, the final step of interpreting the findings into living knowledge resulted in clarifying the effective ways of working for other school leaders seeking to establish an inclusive school culture regardless of socio-cultural context.

Each school was selected after district educational leaders identified that the school had been inclusive of students with diverse learning needs over an extended period of time. Researchers conducted semi-structured interviews on two or three days across a two week period. Each interview lasted about an hour. Each researcher was permitted to access school websites for additional information and to walk around the school making observations. Each visit lasted between 2 to 3 hours.

3. Results

Please note that pseudonyms will be used as data and themes are presented. Due to similarities in the nomenclature of two core filters, school culture will be referred to with a lower case ‘c’, and National Culture (as in Figure 1 above), with an uppercase ‘C’.

3.1. Australian Context

Australia is committed to the 1992 Disability Discrimination Act [26], the 2005 Disability Standards for Education [27], and the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975, which was modified in 2014 [28]. In 2008, Australia ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities [29], including the right to inclusive education. Since 2008, the Melbourne Declaration on Education Goals for Young Australians [30] has guided expectations on all schools to promote equity and excellence. The Inclusive Education for Students with Disability Report [31] identified that most Australian states maintain some form of separate special education in spite of federal (national) government policy espousing inclusive education expectations. In Queensland (where the Australian Case Study School is situated), policy details expectations: high-quality education for all students; active support of the most marginalized and disadvantaged; safe inclusive environments; local responses within local community; and, inclusive education embedded in all school policy and initiatives [32]. A National School Improvement Tool [33] provides a blueprint for state-based school improvement, including expectations of inclusion.

3.1.1. The Australian Case Study School

Forrester Hill, a co-education Queensland state school, which is located in regional Queensland, caters for a diverse clientele from varied socio-economic backgrounds. It has a large special education cohort that is taught by experienced staff. In 2016, 10.2% of the student cohort identified as Indigenous, 2.5% were in home care, 2.75% were from EALD families, and 11.5% of students had diagnosed learning needs. A chaplain, a youth worker, and visiting support specialists work in partnership with staff to cater for the diverse student needs.

In 2015, Forrester Hill became a Positive Behavior for Learning (PBL) school [34]. Behavior expectations, school values, and inclusive ways of working are explicitly taught alongside the Australian Curriculum. Teaching practice is guided by a Schoolwide Pedagogical Framework [35], which was collectively developed by staff. The following extract from the School’s Annual Report, available from the school website states:

The [Forrester Hill] community has a strong sense of identity and culture. We wrap our Forrester Hill Family … in support so each individual is empowered to reach their full potential. Our Vision—Growing Together Learning Forever - and Schoolwide Pedagogical Framework … [are] encapsulated in our metaphor of the Jacaranda Tree ... The roots represent community core values and respect for individual needs; the trunk represents the building of strong relationships; and, the flowers, leaves, seeds and pods are the outcomes and achievements that others can see.

3.1.2. Insights into Lived Experience

An extract from the Principal’s (P) in-depth depiction of lived experience is used as an example of the first phase of data analysis. Within these lived experiences, specific quotes (in quotation marks) have been woven into the narrative.

“Inclusion is what we are about. It’s a moral commitment” I have to my community and students. It’s also my commitment to staff—that they feel competent and capable to address student needs. My role is to be “out and about” in my school, talking, observing, acting—“not sitting behind a desk doing paperwork”. Of course, I do that too, but not at the detriment of my students and staff. We rely largely on quantitative data and observation to justify what we do. I told [District Director] that we had done our research and found existing research to support our plans and “he just agreed to my plan and associated spend. We explore, we get data, we plan, we receive feedback”—“we discuss what we’re setting in place long term and how to collect ongoing feedback” so we can continue “to improve our students’ experiences and outcomes”.

Combined data from all of the participants, as listed in Table 1, illustrate the themes that are related to inclusive school leadership in action that follows.

Table 1.

Australian participant roles and codes.

3.1.3. Australian Themes

Participants referred to the Schoolwide Pedagogy and values visible on walls and in documents. Conversations reinforcing expectations were heard in staff meetings, staff rooms, and classrooms, linking back to the school vision and behavioral expectations. Open communication channels and consistency helped to ensure that expectations about inclusive practice, and how to value and respect others, were made clear. A shared language of expectations kept everyone on the same page (CC). The Principal modelled these expectations, as did the leadership team. Celebration of short-term achievements for students, staff, and the school as a whole, helped to inspire and to motivate. The language used featured hope, high expectations, problem solving based on student need, clear boundaries, and an unequivocal expectation that difference was accepted. Coded quotes and researcher observations illustrate what each theme ‘looked like’, ‘felt like’, and ‘sounded like’ in practice, as observed by the researcher and illustrated by participant words. The voices of the participants, through their narratives, formed four themes.

Theme 1: Strong Inclusive Vision and Direction

A ‘Strong Inclusive Vision and Direction’ was a key theme, echoing the National School Improvement Tool’s first domain for school improvement—an explicit improvement agenda [33]. This was particularly evident within the environment itself. It looked like vision statements, the Schoolwide Pedagogy statements, and images of a Jacaranda tree, behavior charts (linked to the tree metaphor), and magnets heralding the schools’ five priorities: reading, quick-writes, number fact recall, behavior, and attendance. It sounded like “being on the same page” (CC); “we not I or you” (BC); the language of positive behavior expectations; and, students demonstrating awareness of how to respond using positive behavior language norms. It felt calm, structured yet flexible, and inclusive, with mixed students playing together regardless of skin color, language, learning, or emotional need. When staff or student intervention was required, it was done respectfully and firmly.

Theme 2: Distributed Leadership Practice

The theme ‘Distributed Leadership Practice’ or parallel leadership [35] emerged. The Principal built on people’s strengths. She actively engaged staff, students, and parents. She built the capacity of others to lead and established an accepted peer mentoring approach, which was supported by leadership “walk-throughs” (P), that built reflective consciousness of classroom practices reinforcing the school’s five priorities. These actions ensured expectations of inclusion and high standards were met and issues were shared and addressed in a collaborative manner. It looked like teamwork; Working Together Charts for staff activities and students; varied staff members leading discussion and students leading the daily parades. It sounded like “team driven responses” (DP); “acceptance” (T1); “student needs based discussion” (T2); mentoring; problem solving; “professional development needs planning” (CC). Leadership explicitly referenced ‘The Toolkit’ [National School Improvement Tool] (P) and the domain of developing an expert teaching team [33]; in light of that, staff shared practices that worked. It felt like “no blame” (CC); questions were asked and answered according to data that provided “a sense of reassurance” (T2) and validity in decision-making; and, more than anything else, it felt like “respect” (HOSE).

Theme 3: A Schoolwide Pedagogy Guides Teacher Practice

Related to the previous theme emerged ‘Schoolwide Pedagogy Guides Teacher Practice’ for the development of “expert teaching teams” (P). Budgetary decisions were made according to school wide focus, and student physical, cognitive, or emotional need. Small pockets of funding became additional teacher aide support, collective professional development, or targeted individual development. It looked like “data walls” (CC) with various data displayed; student goal charts; regular debriefing meetings; social justice needs meetings; community newsletters documenting learning opportunities for families; “extension opportunities” for students; and the sharing of professional practice with the wider community. It sounded like “data rich conversations” (T2); “knowing students by name” (BC); “a shared pedagogical language” (CC); positive relationships; and, negotiation, “advocacy” (T1), and a small school mindset because “we never turn a student away” (P). It felt like support for the challenges faced by teachers when a student presented in class with a need not previously encountered. It felt like collective “commitment to excellence” (CC).

Theme 4: An Adaptable Student Centered Community

There was a real sense of ‘An Adaptable Student Centered Community’. Community support was fostered with volunteers running wood working clubs, and helping with musical performances, reading groups, targeted activities for Australian Indigenous students, and much more. It looked like “organized inclusive chaos” (ST). There was always something on and something being planned. Teachers looked “deeper than just behavior” (BC) in order to connect with children. Staff would “do what it takes” (P) and “we try until something works” (BC). Social justice was modelled by the Principal and had become a part of a whole community focus and commitment to inclusion. It sounded confronting at times when a parent, a student, or a staff member did not wish to take on the responsibility for being inclusive, but this was “not an option” (T1). It also sounded like “asking for help” (T2); and, “knowing it would be given—one way or another—either straight away or as soon as it was possible according to priorities” (ST). It felt like inclusion was a given, regardless of socio-economic status, learning need, cultural difference, or other form of diversity “everyone was accepted” (ST). It felt “ok to make mistakes” (BC) and staff were encouraged to take supported risks to address student needs.

3.2. Canadian Context

Education in Canada for the most part is publicly funded, with the majority of students attending publicly funded schools, leaving only a small percentage attending private schools. In Canada, education is under provincial jurisdiction, and the school, in this study, is within the Province of Ontario. It is the Ministry of Education of the Ontario Government that governs policy, funding, curriculum planning, and direction in all levels of public education, including setting the agenda for inclusive leadership practices within schools.

Ontario’s revised resource guide ‘Equity and Inclusive Education in Ontario Schools’ [36] provides support for school boards and schools with the important work of continuing to foster an equitable and inclusive education system. It is the belief of the government, as well as school personnel, that equity and inclusive education is an ongoing process that requires shared commitment and leadership to meet the complex issues and concerns of Ontario’s communities and schools.

3.2.1. The Canadian Case Study School

The Ontario school (Riverdale) is located in a low socio-economic area of a large urban city and it caters for students from ages 4–12. Riverdale’s school mission is to be a vibrant teaching and learning center that maximizes each child’s wellbeing, and literacy and numeracy potential in a safe, healthy, inclusive, and collaborative environment. Riverdale has a very complex and multi-cultural student population, with 26% special needs (excluding gifted); 75% English Language Learners (ELL); 6% are under Children and Family Services care; and, 4% are Indigenous, with the school involving outside agencies to help support its diverse student needs. A part-time Multicultural Liaison Officer is employed to support staff with translation services, both verbally and in written format, and to liaison with newcomers and ELL families.

3.2.2. Insights into Lived Experience

In line with a growing body of knowledge, and research highlighting a direct connection between effective leadership and improved student achievement and well-being, the leaders from Riverdale School who participated in the study all echoed their belief in their vision of equity and inclusion. They all cited the resource guide, which is mentioned above, as a starting point on this ever-evolving journey. This extract from the Principal’s (P) narrative provides insights into her lived experience as the leader of this inclusive school community.

“I need to ensure that the work of creating an inclusive school is ongoing” so that we provide a caring, inclusive, safe and accepting environment that “supports the needs of ALL students. My role is to engage staff in inclusive education”. Inclusive education “requires shared commitment and leadership” to tackle very complex issues found within the school community. At our school “we have a strong emphasis on additional class support, however, we are still not fully inclusive”, as we still have “special education withdrawal and ELL withdrawal, which is becoming less and less”. The district is moving away from withdrawal “and into total in-class support”. It is a mindset of some staff that “withdrawal is still better”, so creating an inclusive school has taken time, and it is “still on-going. Some staff need to ‘shift’ their thinking and ideals”.

Table 2 lists all the participants whose data was collected. The data captured the lived experiences of the formal and informal school leaders at Riverdale School.

Table 2.

Canadian participant roles and codes.

3.2.3. Canadian Themes

Data were examined for themes common to all of the interview participants. Four themes are illustrated by coded quotes and researcher observations according to what each ‘looked like’, ‘felt like’, and ‘sounded like’ in practice. The language of all five participants referred to the school vision, encompassing values and beliefs, and visible on the walls, located in school documents, and evident through traditions, such as monthly ‘spirit’ assemblies. Conversations that reinforced these values, beliefs, and expectations were heard in staff meetings, staff rooms, the school office, hallways, and in classrooms. Staff and student behavior expectations were clearly linked back to the school vision. It was very important to continually communicate, through various methods, to ensure that expectations about inclusive practice and how to value and respect others were explicit. There was a common language being reinforced, helping staff to view inclusivity through the same lens. Staff emphasized how the Principal and Vice-Principal modeled inclusive expectations. The language spoken was built upon hope, learning, expectations, problem solving, behavioral boundaries, social justice, and equity.

Theme 1: Student Centered Practice and Decision Making

‘Student Centered Practice and Decision Making’ was the first resounding theme. All of the students can be successful if supports are provided was painted on the wall in the front entrance way. The emphasis in classrooms is on “additional class support” (T2). It was also a wide-spread belief amongst all staff and the language used in both formal and informal conversations placed an emphasis on learning for all. “We believe and promote that All Students Can Succeed. It is a motto, a belief…. It is engrained within our staff, they do believe this” (T). “It is the belief that all students can be successful, this is inclusivity at its best. All students belong and all students can and will be successful” (P).

Theme 3: On-going Commitment to Inclusive Education

‘On-going Commitment to Inclusive Education’, was established through a school-wide focused vision to plan for student achievement, by committing to the importance of knowing each individual student’s needs personally, emotionally, socially, and academically. A commitment by teachers was made to include all students by planning and assessing of, for and as learning, both individually and collectively. Teachers discussed achievement not only in terms of academic accomplishments, but also in terms of each individual student meeting with success in their area of talent. “Teachers go out of their way to discover the hidden talents and abilities of all students and intentionally focus on the strengths of the students, not their weaknesses” (T3). The language in the classroom was based on positive inclusivity, emphasizing student’s strengths. “Each student was encouraged to focus on his/her strengths” (T2) and the strengths of their classmates. It was a school culture that is founded upon “building each other up, not tearing each other apart” (VP). “Support is at hand so that students remain in the classroom with their peers” (T2). The special education and English as a second language teachers came into the classroom and rarely withdrew students.

Theme 4: School-wide Approach to Universal Design for Learning

The final theme, ‘School-wide Approach to Universal Design for Learning’ [37], was evident in discussions and observations that were made during school visits. Without collaboration and the building of trust the staff would not be able to work together and would not be cohesive and student achievement levels would not be as high. The levels are high because “we all plan together” (T1). It is as a school-wide approach to Universal Design, a set of planning principles based on learning sciences research, led by the Principal, yet “enacted by the staff” (T2). Teachers base decisions and execute these decisions according to sound theory and pedagogical practices. There was a strong balance of theoretical and practical instruction occurring. “Differentiating the curriculum is important for my students so that they can learn and meet with success. It is my responsibility. I reflect on my practices so that I can incorporate what I have learned as a teacher. My students benefit because of it” (T3). This attitude, and mind set to become an expert teacher who wants to develop his/her practice based on theoretical understandings and Universal Design for Learning principles, so that his/her students will become the best that they can be, was held by an overwhelming majority of staff and was supported by professional development.

3.3. Colombian Context

The 1991 Colombian Constitution safeguards the conditions and opportunities for all citizens to ensure their human rights. The 1618 Law of 2013 and the CONPES 166 [38] propose guidelines for the implementation of policies aimed at guaranteeing access to good quality services and full social inclusion for people with disabilities. Discouragingly, data revealed 90% of children with disabilities did not attend mainstream education, and those that did primarily attended public schools with participation further decreasing in higher education contexts [39]. The alignment of policies and laws with international standards has led to inclusion now being seen as a “rights issue and not simply a matter of public health or rehabilitation, as it had previously been understood in national public policy” [40]. The Ministry of Education (MEN) regulates all education services in Colombia and recently issued the Decree 1421 [41] proposing that inclusive education be centered on curricular flexibility and the use of Universal Design for Learning [37] principles.

3.3.1. The Colombian Case Study School

Colegio Nuevo Mundo is a co-educational private school with 300 students in pre-school, primary, and high school. Local authorities in Bogotá, Colombia, recognized Colegio Nuevo Mundo as an inclusive school that in 2017 catered services for 9.3% students that were diagnosed with different conditions (Down syndrome, autism, hearing impairment, cognitive deficit, and so on). It also offers services for students whose first language is not Spanish (4.6%) and for students with varied religious backgrounds (1.7%). Although small, this percentage is significant because Catholicism has a high number of adherents and it is commonly practiced in both private and public institutions [42]. The Dynatos program is an interdisciplinary support center within the school offering specialized therapies for students, and the Pedagogical Support Group (GAP in Spanish) program helps to support teachers, parents, and staff in aligning pedagogical activities. The research was conducted in the junior section of the school and combined data from all participants (listed in Table 3) illustrate the themes that are related to inclusive school leadership in action.

Table 3.

Colombian participant roles and codes.

3.3.2. Insights into Lived Experience

Despite the fact that the school officially began its inclusion program in 2005, when a student with Down syndrome was admitted for the first time in the school, the quest for inclusion can be traced to the foundation of the school. In 1940, the Principal believed that opening access to women in education was the means to challenge the prevailing patriarchal structures of the Colombian society and founded the school, establishing its slogan ‘Supportive and productive inclusion for women’. This slogan was the platform for extending the idea of opening the doors to a more diverse population. Members of the school began to gain knowledge and experience about education for students with special conditions, and over time more students entered the institution.

The spirit of inclusion appears in documents and in the words of the participants and can be seen in the lived experience of the Principal (PCo):

I “believe that the Principal must be convinced of inclusion. Believe that all children should have possibilities to learn”. We, as Principals, must be “convinced, trust, and believe” in this project. We work diligently, making “curricular adaptations”, helping with “flexibility” and the creation of strategies. For inclusion to work, I must be a “pedagogical leader and obviously an administrative and organizational leader”. I must be there, available for all. For inclusion to work, I must be “willing to guide all personnel” because we must understand that “to meet the needs of our children we must work hard”.

Combined data from all of the participants (listed in Table 3) illustrate the themes that are related to inclusive school leadership in action.

3.3.3. Colombian Themes—(Please note that the original transcripts for this section were in Spanish and the wording has therefore been translated into English for the purpose of this paper)

The language that was used by participants revealed a strong shared conviction that inclusion is possible. The Principal’s vision regarding social justice played a crucial role in making this vision resonate throughout the school community. Teachers and staff stated that believing in inclusion necessarily involves sensitizing the community, including parents, by raising awareness about diversity, thus playing a key role in confronting the fears and stereotypes that permeated many schools in Colombia. A clear set of objectives and organizational structures, coupled with curricular flexibility and support that was provided by specialized teams (the Dynatos and GAP teams) facilitated teachers’ adaptation of classroom activities and materials for all students. Permanent open communication channels exist, from formal meetings where individual cases are analyzed, through to informal chats among colleagues, creating an atmosphere of collaboration that facilitates solving problems, seeking for appropriate pedagogical solutions, while strengthening the social fabric among teachers. The ongoing support of the GAP team, the Dynatos group, and the Principal, in addition to continuous professional development opportunities within and outside the school, were highly valued by the teachers. For teachers and staff, inclusion meant challenge and growth. It implies reflection, professional learning opportunities, and team driven responses with all, embracing the creation of a natural and safe environment for all children, fostering voluntary behaviors of participation and involvement.

Theme 1: Reinforcing the Belief that Inclusion is Possible

The language that was used by teachers, assistants, and the Principal illustrates the first theme of ‘Reinforcing the Belief that Inclusion is Possible’. Creating a sense of unity and belongingness to the school looked like sharing snacks, walking around in pairs or in small groups, participating in dance rehearsals and sport activities, and being engaged in classroom activities, evidenced in expressions, such as “I think that the key to make this possible is to believe that there is a place and a space to be with each other” (PCo) or in trusting in the capacities of all people and “trust our children. We trust that we [teachers and staff] can contribute” (CCo). It is felt by all because of efforts to “sensitize the school community beginning with the children themselves making students aware of the importance of working together” (SG2). The belief in inclusive education is also evidenced in the choice of words for the programs e.g., Dynatos is a word that is derived from Greek that means power, faith, force, movement, and advancement, which are concepts that describe the foundation of the project (GAP document).

Theme 2: A Strong Leader who Builds Capacity in Others

Community trust in this school’s inclusive education program is associated with the theme of having a ‘Strong Leader who Builds Capacity in Others’, “a leader who is completely convinced of inclusion” (CCo), a person with “high resilience capacity characterized by assertive communication skills, open-mindedness and an eager[ness] to listen to new ideas” (SGA1). This looked like debriefing meetings, “continuous reflection and evaluation of the strategies used to serve each student” (CCo, PCo, SGA2). It sounded like “clear objectives, plans and ongoing revision” of school plans to serve its community and “induction sessions to help teachers cope with the deficiencies and gaps in teacher preparation programs” (PCo), and to help the community confront their fears regarding the inclusion of students with special needs. It felt, at first, like rejection by some, because “at the beginning the project was rejected by many” (TCo1), but now inclusive school practices are fully embraced. Currently, there is “an increasing tendency for families to come and celebrate with us and support us (CCo) because this is worth fighting for” (CCo).

Theme 3: Curricular Flexibility and Collective Effort

‘Curricular Flexibility and Collective Effort’ lies at the core of practices in the school. “Although the curriculum follows the official, national guidelines, it is modified to meet the particular needs of the students” (CCo). To do so, members of the GAP team, in partnership with teachers, using Universal Design for Learning principles [37] “adapt activities and materials for all students and share them with students’ families translat[ing] policies” (TCo3) into assertive and efficient pedagogical practices. It looked like permanent structures for facilitating communication and collaborative work amongst support groups, teachers and families resulting in “a sense of collectiveness” (CCo) and ensuring “significant learning opportunities for all students regardless of their condition” (CCo). “Decisions were collectively constructed” (TCo1). Consensus on the best alternative to deal with a problem came from “deep understanding of each student’s situation, research on the topic and feedback” (TCo3) on the alternatives proposed. Acknowledging flaws in the proposals and working on overcoming them was accepted as part of the group efforts to improve the educational experiences offered to students.

Theme 4: Natural and Voluntary Student-centered School Community Environment

The theme ‘Natural and Voluntary Student-centered School Community Environment’ was seen to be the result of initiatives that were focused on engagement. It looked like participating in science projects, “not having separate schedule—dancing and playing” (TCo1). It was reflected in programs like “Best Buddies”, and in the communication strategies that the school used to share information, like posters and banners where photos of all students are displayed and on the web site where student academic and social activities were shared. “It looked like transcending the walls of the classroom. It felt like any effort was a small but significant drop to,…a contribution to, social inclusion” (PCo) as more students were being invited by a broader range of peers to social activities outside the school, like parties and going to the mall or to the movies. “It still feels like a challenge as we need to narrow the gap in access to higher education” (PCo). It feels like peer work and collaboration in the classroom and being part of all activities proposed (a researcher observation).

4. Discussion

As the research progressed it became apparent that, although evident, the varied socio-cultural indicators found within the data had less of an impact on school based inclusion practices than had originally been anticipated. Instead each school culture had emerged with similar characteristics, regardless of National Culture or other socio-cultural factors, such as family cohort differences. Each leader shared a similar approach to developing and maintaining the inclusive ways of working in action within each school.

There are obvious limitations to this data when they originate from only one school per country. Further research needs to be conducted to ascertain levels of teaching staff experience, funding access, or policy accountabilities at a system level, all of which may have also influenced findings. Nonetheless, an overarching theme resonated across all school contexts. Each community, as a whole, supported the ‘journey to inclusive school practice’. For this journey to be successful, the school Principal prioritized supported capacity building and professional learning that was focused on addressing individual student and staff need. Slight nuances did exist in wording and in cultural and contextual practice and yet as we analyzed the data for themes (without pre-conceived ideas of what these themes would be) the resonance across all of the case studies was clear and unmistakable, as can be seen in Table 4. Each theme was firstly derived by the researcher/s who worked within that school, before being discussed as a team. After team discussion wording was adjusted to cater for additional insights. From this collaborative review phase emerged remarkably aligned themes (see Table 4).

Table 4.

A synergy of themes supporting the journey to inclusive school practice.

The culture within each school was led by a strong committed leader and leadership team. All of the schools had a vision of inclusion and a strong sense of direction that was underpinned by school-wide pedagogical practices with two schools committed to using the Universal Design for Learning as their school-wide framework, whilst staff at the other had collectively developed their own Schoolwide Pedagogy that was based on contextualized wording of similar principles. At the heart of each school community’s commitment to inclusion was the ‘child’. Each student was seen as having the right to have their needs met, whether these be cultural, emotional, psychological, cognitive, or physical. Leaders and teachers were prepared to do whatever was needed to ensure that the students’ needs were met. This commitment translated into action which involved “changes and modifications in content, approaches, structures and strategies” [2], adhering to UNESCO’s understanding of the process of inclusion, which saw of each of these schools effectively respond to a wide diversity of student needs.

The three schools studied were from varying Cultural contexts, however, they shared school culture similarities. Relying on Schein’s definition of organizational culture as having three concept levels—artefacts, espoused beliefs and values, and basic underlying assumptions [7], the synergies between the schools was evident. At the visible level, all three schools had vision statements, leadership practices that empowered others, and a school-wide approach to teaching and learning. Artefacts included a language of inclusivity, schools’ website messages, positive displays of encouragement, and observable school celebrations that honored and included all of the students. Embedded within the three schools was a set of beliefs and values regarding inclusivity that embodied an ideology that guided the ways of dealing with differences and the promotion of community acceptance. Staff were able to articulate these values and beliefs into an operational philosophy for bringing the school together through recognizing uniqueness and providing individualized support for all students. The basic underlying assumption, the essence of each participant’s lived experience, was that inclusion was not optional. Inclusion was what the staff believed in and how they behaved. It was their consensual reality, their way of being.

The Principal, in all three organizations and across all three contexts, was a visionary and a leading role model for inclusion. The Principals promoted shared leadership encouraging all teachers to help build and improve upon a culture of inclusivity that promoted shared norms and assumptions about how inclusive practice should occur. Each Principal promoted norms and assumptions about social justice and moral leadership maximizing the combined efforts of all leaders within the schools to ensure greatest impact on promoting, modeling and enacting inclusivity. Teachers were empowered to build on a vision for inclusion, to trust, and mutual respect sharing in the concept of collective commitment to leading inclusive practice. Both formal and informal leadership roles created and maintained school cultures built upon social responsibility, connections, and community. Leaders modelled a sense of responsibility and accountability for the learning of all the students and for the lives of all school community members. The leadership at all three schools demonstrated a profound awareness as to the importance of meeting the needs of all students and held fast to their advocacy role.

Socio-cultural influences did exist and in all three contexts, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions [16,25] of uncertainty avoidance, long-term orientation, and femininity resonated. School leaders were willing to assume challenges and to make tough decisions, often working to counter traditionally accepted social practices, even at the expense of losing families and staff who felt reluctant to accept the new and inclusive school direction. This meant taking risks, navigating unexpected situations and circumstances, trusting those affiliated to the school’s vision of inclusion, and opening the road to trial and error, and data-driven decision making. Within the individualistic/collectivist dimension, there was a tendency by all of the leaders to promote group and collective effort and to identify as members of an inclusive culture. In the socio-cultural contexts of Australia and Canada, the data revealed a more distributed leadership approach with ‘we’ rather than ‘I’ being used when referencing the staff as a whole. In both these countries there was also a system developed guide for inclusive practice that was referenced frequently. In the Colombian case, this was not evident, and instead, internal support groups were the primary source of inspiration for inclusive practice. In many ways the Colombian Principal’s commitment to inclusion was outside the national norm, although she did use the collective ‘we’ to refer to school Principals as a ‘position’, which is possibly indicative of the more traditional hierarchical Cultural structure that is still present within Colombian society and evidenced in the close link between church and state [42]. Power distance also presented differences between Colombian Culture and that of the other two countries, with both state and private education reflecting religious affiliation and ambiguity in the understandings of inclusion at the policy level.

5. Conclusions

Over time, each of these school leaders had established an inclusive school culture where individuals had learned to share the assumption that they must be problem solvers and learners [7], in order to ensure that all students were included in the learning process. Individual needs had to be catered for effectively. The role of the Principal in each context was crucial because each set the cultural tone within their school. The overarching theme pertinent for all of the schools was that they were each on a ‘journey to inclusive school practice’, and for this to be achieved, each Principal’s key strategy was the same; to support capacity building and professional learning focused on addressing individual student and staff need. In the Canadian and Australian contexts, the language that was used showed a strong distributed (or parallel) leadership model [35] in action. Although being less obvious in the Colombian context, the Colombian principal still sought to empower others and to build on their strengths. Each leader espoused a belief that all children want to and can learn when provided with the right support. In order for this to happen, they actively built the capacity of their teaching and support staff, and expected that they, in turn, would be willing to learn by seeking and accepting feedback and by displaying flexibility when faced with challenges. Although at times each Principal’s positive assumptions were challenged when staff or families with conflicting views left the school, those that remained were committed to their beliefs and assumptions, and ultimately a strong inclusive school culture emerged and was sustained.

This discussion has focused on the contexts of Australia, Canada, and Colombia where inclusive schooling is a continuing process, not a single event. It involves a way of thinking that recognizes the right of all children to be educated in an inclusive environment. For most educators, the idea of full inclusion is an unattainable ideal given the present resourcing and teacher training. Notwithstanding, there are changes that a committed school leader can realistically make that will, in turn, alter school culture and ensure the inclusion of all students, no matter their need or socio-cultural context.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the inspirational work of the various schools involved in this research.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this paper by conducting research in the schools, by analyzing data, by collaboratively discussing and writing up the data and determining the answers to the research questions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Taylor, J.E.; Filipski, M.J.; Alloush, M.; Gupta, A.; Valdes, R.I.R.; Gonzalez-Estrada, E. Economic Impact on Refugees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7449–7453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. Policy Guidelines on Inclusion in Education. Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001778/177849e.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2018).

- Abawi, L.; Oliver, M. Shared Pedagogical Understandings: Schoolwide Inclusion Practices Supporting Learner Needs. Improv. Sch. 2013, 16, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, P. Talking with Children about Prejudice and Discrimination; Barnardos and Save the Children: Belfast, Ireland, 2002; Available online: http://www.barnardos.org.uk/fair_play_booklet-2.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Maclean, R. (Ed.) Life in Schools and Classrooms: Past, Present and Future; Springer Nature: Singapore, Singapore, 2017; ISBN 978-981-10-3652-1. [Google Scholar]

- Forlin, C.; Chambers, D.; Loreman, T.; Deppeler, J.; Sharma, U. Inclusive Education for Students with Disability: A Review of the Best Evidence in Relation to Theory and Practice; Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth [ARACY]: Canberra, Australia, 2013; Available online: https://www.aracy.org.au/publications-resources/command/download_file/id/246/filename/Inclusive_education_for_students_with_disability_-_A_review_of_the_best_evidence_in_relation_to_theory_and_practice.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2017).

- Schein, E.H. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 3rd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2004; ISBN 0-7879-6845-5. [Google Scholar]

- Trompenaars, F.; Turner, C.H. Riding the Waves of Culture; Understanding Cultural Diversity in Global Business; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998; ISBN 1-85788-176-1. [Google Scholar]

- Irawanto, D.W. An Analysis of National Culture and Leadership Practices in Indonesia. J. Divers. Manag. Second Quart. 2009, 4, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miskolci, J.; Armstrong, D.; Spandagou, I. Teachers’ Perceptions of the Relationship between Inclusive Education and Distributed Leadership in Two Primary Schools in Slovakia and New South Wales (Australia). J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2016, 18, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. 1994. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- Smyth, J. Speaking Back to Educational Policy: Why Social Inclusion will not Work for Disadvantaged Australian Schools. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2010, 51, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnukainen, M. Inclusion, Integration, or What? A Comparative Study of the School Principals’ Perceptions of Inclusive and Special Education in Finland and in Alberta, Canada. Disabil. Soc. 2015, 30, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.; Armstrong, A.C.; Spandagou, I. Inclusion: By Choice or Chance? Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2011, 15, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; Palincsar, A. Sociocultural Theory n.d. Available online: http://dr-hatfield.com/theorists/resources/sociocultural_theory.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-8039-7323-7. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978; ISBN 0-674-57629-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. The Culture of Education; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; ISBN 0674179536. [Google Scholar]

- Abawi, L. Introducing Refractive Phenomenology. Int. J. Mult. Res. Approaches 2012, 6, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husserl, E. Ideas: General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology; George Allen & Unwin: London, UK, 1931. [Google Scholar]

- van Manen, M. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy; The Althouse Press: London, UK, 1997; ISBN 10: 0920354424. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Smith, C., Translator; Humanities Press: New York, NY, USA, 1964; ISBN 081-010-1645. [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop-Margison, E.J.; Strobel, J. Constructivism and Education: Misunderstandings and Pedagogical Implications. Teach. Educ. 2008, 43, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malterud, K. Qualitative Research: Standards, Challenges and Guidelines. Lancet 2001, 358, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-07-177015-6. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government. Disability Discrimination Act 1992. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C2004A04426 (accessed on 20 November 2017).

- Australian Government. Disability Standards for Education 2005. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/disability-standards-education-2005 (accessed on 20 November 2017).

- Comlaw.gov.au. Racial Discrimination Act 1975. Available online: http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2014C00014 (accessed on 16 January 2017).

- The United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities; Treaty Series, 2515, Article 44; The United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- MCEETYA. Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians, 2008. Available online: http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2015).

- Research Alliance for Children and Youth. Australian Inclusive Education for Students with Disability. Available online: https://www.aracy.org.au/publications-resources/command/download_file/id/246/filename/Inclusive_education_for_students_with_disability_-_A_review_of_the_best_evidence_in_relation_to_theory_and_practice.pdf (accessed on 4 July 2017).

- Queensland Government Inclusive Education Policy Statement. Available online: http://education.qld.gov.au/schools/inclusive/ (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Australian Council for Educational Research National Improvement Toolkit 2016. Available online: https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?paper=1019&context=tll_misc (accessed on 10 December 2017).

- Mooney, M.; Dobia, B.; Power, A.; Watson, K.; Yeung, A. Positive Behaviour for Learning: Investigating the transfer of a United States System into New South Wales DET. Available online: researchdirect.uws.edu.au/islandora/object/uws%3A132/datastream/PDF/.../citation.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2018).

- Crowther, F. From School Improvement to Sustained Capacity: The Parallel Leadership Pathway; Corwin: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 9781412986946. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Realizing the Promise of Diversity … Ontario’s Equity and Inclusive Education Strategy, 2014. Available online: http://www.edu.gov.on.ca/eng/policyfunding/equity.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Israel, M.; Ribuffo, C.; Smith, S. Universal Design for Learning Recommendations for Teacher Preparation and Professional Development. Document No. IC-7 CEEDAR Centre. Available online: http://ceedar.education.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/IC-7_FINAL_08-27-14.pdf: (accessed on 22 March 2018).

- Departamento Nacional de Planeación. Política Pública Nacional de Discapacidad e Inclusión Social (Documento Conpes Social 166); DNP: Bogotá, Colombia, 2013. Available online: https://www.minsalud.gov.co/sites/rid/Lists/BibliotecaDigital/RIDE/INEC/IGUB/CONPES1.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Sarmiento, A. Situación de la Educación en Colombia. Preescolar, Básica, Media y Superior. Una Apuesta al Cumplimiento del Derecho a la Educación para Niños, Niñas y Jóvenes; Gente Nueva Editorial: Bogotá, Colombia, 2010; ISBN 978-958-8402-20-8. [Google Scholar]

- Correa-Montoya, L.; Castro-Martínez, M.C. Disability and Social Inclusion in Colombia; Saldarriaga-Concha Foundation Press: Bogotá, Colombia, 2016; p. 8. ISBN 978-958-59203-9-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación Nacional-MEN. Decreto 1421 por el Cual se Reglamenta la Atención Educativa a la Población con Discapacidad, 2017. Available online: http://es.presidencia.gov.co/normativa/normativa/DECRETO%201421%20DEL%2029%20DE%20AGOSTO%20DE%202017.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Daniel, H.L. Religion and Politics in Latin America: The Catholic Church in Venezuela & Colombia; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2014; Available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/ (accessed on 26 March 2018).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).