Learning and Living Overseas: Exploring Factors that Influence Meaningful Learning and Assimilation: How International Students Adjust to Studying in the UK from a Socio-Cultural Perspective

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Transition to Higher Education

1.2. Rationale

1.3. Transition to HE for International Students

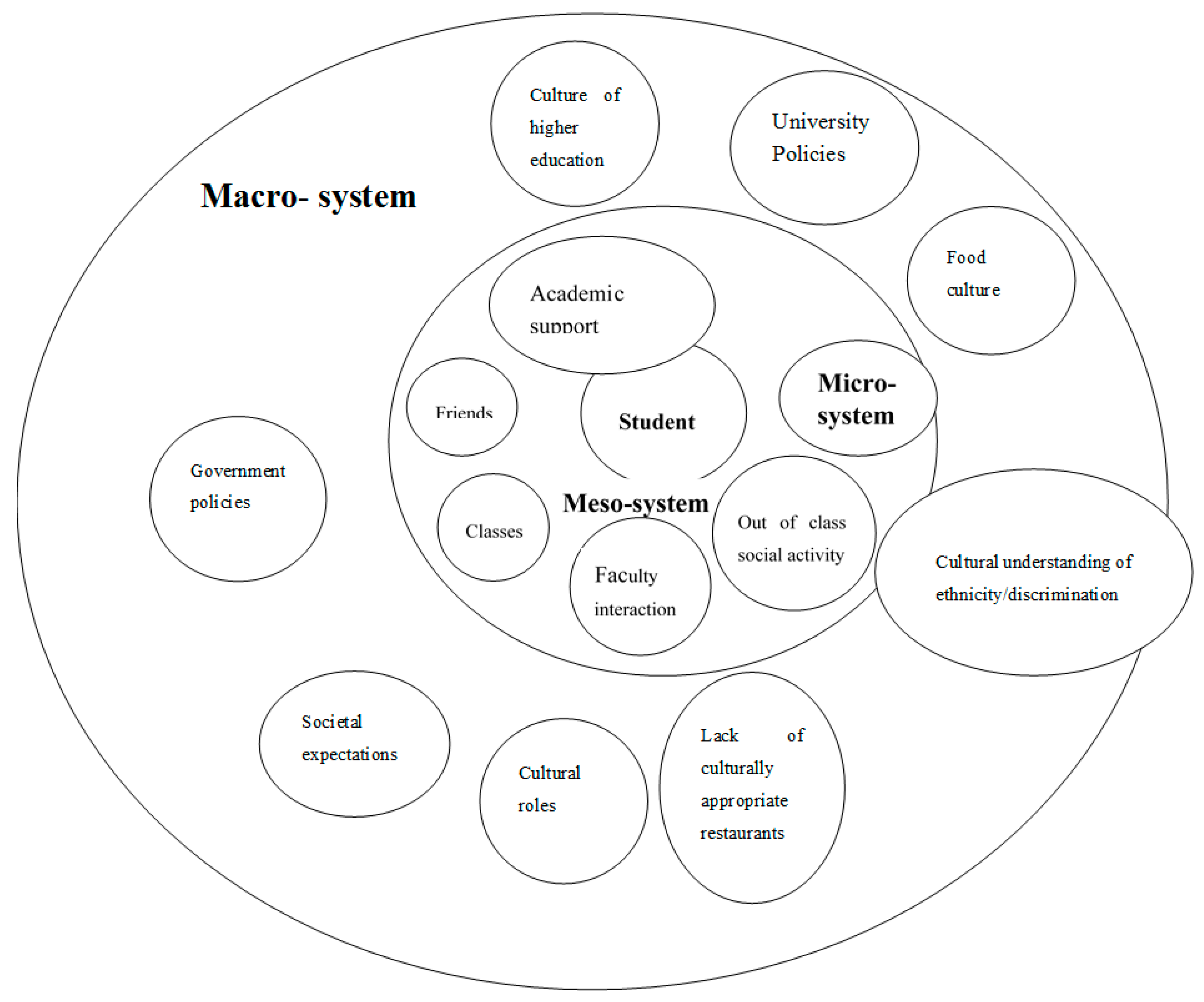

1.4. Theoretical Framework

1.5. Aims

- (1)

- Explore the socio-cultural factors that influence how international students adjust to living and studying in higher education in the UK;

- (2)

- Consideration of supporting practices which could assist international students in their transition to Higher Education.

2. Methodology

2.1. Participants

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

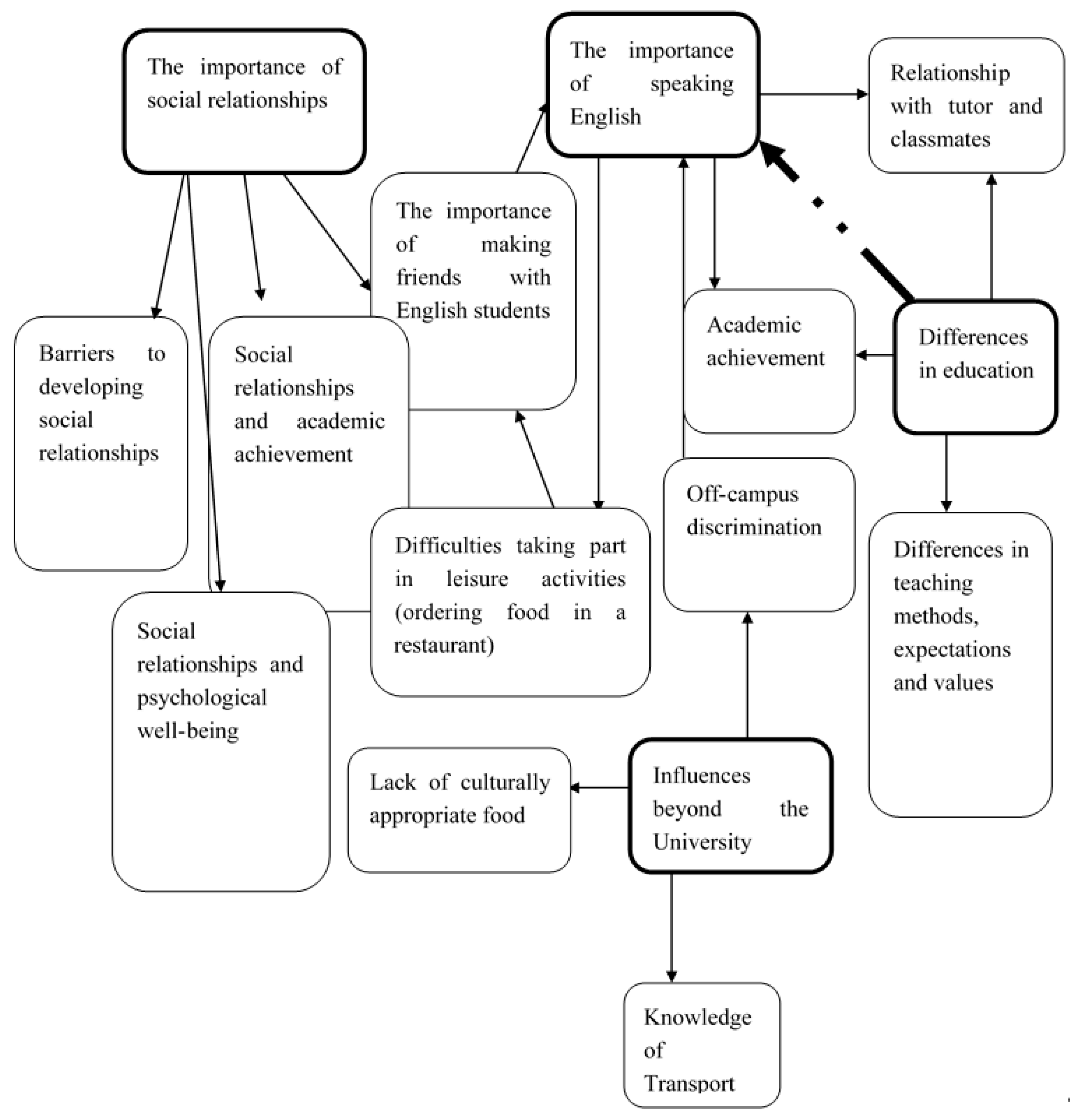

3. Results

3.1. Analysis/Discussion

3.2. The Importance of Social Relationships

I didn’t want to leave my comfort zone, especially because halls were so noisy, so I stayed with my boyfriend. We didn’t communicate with anyone, so at the end of year 1 hadn’t spoken to anyone or anyone on my course, so I didn’t have any friends at first, I was so lonely and it affected my confidence... Before if I was stressed during exam period, I could talk to my friends and it would be fine. But here I can’t talk to anyone and then I get depressed and then I can’t concentrate on my work and I started to miss my lectures in the first year.

The first day was really tough, it was very over whelming, and I was traumatised. I went to bed straight away. But the next morning I woke up it started to get better, my house mate let me borrow his phone to ring my family and then he came into town with me, showed me around and helped me find a job…I met lots of friends from my job and it gave me more confidence, and then we went out and I met more friends from different places.

I wanted to understand their mentality; it was so different to Bulgarians. I wanted to be friends with them so I could understand how they think, their views, their beliefs, their traditions and I thought maybe this would help me, and it did...I realised that it’s not polite to talk about politics here, but that’s all we talk about at home, so now I learnt how to ‘small talk’.

I started to speak to people. I made a best friend from England who always helped me and took me to places and I wasn’t afraid to try different words or phrases because I knew if I messed up she wouldn’t laugh, she would just say you don’t say that here.

In Korea, University girls put on high heels everyday but British girls they only wear flat shoes. People started to ask why you wear these shoes every day, and they thought it was weird, so I started to wear flat shoes too.

3.3. The Importance of Speaking English

I was very clever in Korea but now I feel stupid because I don’t understand everything as well as everyone else in my class, because I do not speak their language, and I struggle. My grades were not very good in first year.

In my first year I was really timid in class, especially when we did group work. English is so difficult because even though I can understand and I thought about what grammar is incorrect and correct, when you actually try to communicate in English you don’t have enough time to think and work out what the person is saying so it becomes hard to communicate.

I was scared to ask my tutor for help because I thought that he wouldn’t be able to understand me and I wouldn’t be able to understand him and I was scared the he might think I’m stupid, and the work was really hard, especially because I did it alone.

I really wish to have lots of English friend to improve my language but it’s hard to spend time together when they don’t understand me speaking.

I didn’t really go out because I was scared of how to ask for things. I remember when I first came and I went to a restaurant and I ordered steak, fillet steak, and they didn’t understand me so I had to write it down. I have to write everything down wherever I go. People often get angry or laugh and mock my accent, so it put me off going out unless I really needed to for a while.

3.4. Influences Beyond the University

When I feel tired or ill we usually eat a certain soup and rice but here I cannot buy it or any Korean stuff so I ate hamburger, this makes me feel really sad and homesick.

In Korea, going out for food was our main social activity, we would always meet up for food or even if we went for a drink, we would order soup and fruit, we sit there, and everyone talks. But I don’t really like the food here so we don’t go out much and there’s not really much else to do, I miss it.

Manchester really helps when I’m homesick, I go to the restaurants and eat my home food with my friends and I feel better.

I had a lot of issues with managing money in my first year because the currency was so different, so if it was £1 here it was 100 in Indian currency. I just thought, oh it’s only 1 it’s so cheap and this was a real problem for me because I ended up spending far too much.

The first time I did my food shop I spent that much money that I had to walk to uni for the rest of the month because I couldn’t afford the bus. I felt like we had no help, and these things are hard to figure out on your own. I never did a food shop at home never mind in a different country with different money.

When I arrived in the UK I got a taxi from Manchester airport to Huddersfield which cost me £80. I had no idea you could get the train. I had no idea I was meant to. I was so annoyed.

3.5. Differences in Education

In Korea, students always say ‘teacher’ before we ask a question, we always respect our teacher. But when I say teacher when I have a question here, other people start to laugh at me. I thought a student shouting out was very rude, but for British people its normal. I find it hard to ask questions this way, so I prefer to stay quiet...In Korea if we get the answer wrong it’s really bad, but in UK class British people just shout out even when they don’t know the right answer. I found that we had to investigate and discuss the answers ourselves and this was hard, I struggled with my work because I did not want to ask.

I prefer the teaching methods at home, I felt more supported. I knew whether I was right or wrong because [the] teacher told us.

I felt extremely out of my comfort zone in the lecture halls I would never ever ask a question in front of all those people because of my language, and their language and the lecturer seemed like this really scary, really important figure of authority. It wasn’t like in Bulgaria, learning felt a lot more casual at home and I could just go to the desk and ask my question, but it felt scary and so unfamiliar here.

I’ve learnt how to discuss my answers. I like discussing the answers with my class mates, I realised that it’s okay to be wrong here.

4. Conclusions

5. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Phase | Description of the Process |

|---|---|

| 1. Familiarising yourself with your data: | Transcribing data (if necessary), reading and re-reading the data, noting down initial ideas. |

| 2. Generating initial codes: | Coding interesting features of the data in a systematic fashion across the entire data set, collating data relevant to each code. |

| 3. Searching for themes: | Collating codes into potential themes, gathering all data relevant to each potential theme. |

| 4. Reviewing themes: | Checking in the themes work in relation to the coded extracts (Level 1) and the entire data set (Level 2), generating a thematic ‘map’ of the analysis. |

| 5. Defining and naming themes: | Ongoing analysis to refine the specifics of each theme, and the overall story the analysis tells; generating clear definitions and names for each theme. |

| 6. Producing the report: | The final opportunity for analysis. Selection of vivid, compelling extract examples, final analysis of selected extracts, relating back of the analysis to the research question and literature, producing a scholarly report of the analysis. |

| a. The importance of Social Relationships | a1 The importance of Speaking English | a2 Differences in Education | a. Influences beyond the University |

|---|---|---|---|

| (b) Barriers to developing | (c) Academic achievement | (c) Relationship with tutor and classmates | (b) Lack of culturally appropriate food |

| (b) Social relationships & academic achievement | (b) Off-campus discrimination | (c) Academic achievement | (b) Knowledge of transport |

| (b) Social relationships & psychological wellbeing | (c) Relationship with tutor and classmates | (b) Differences in teaching methods, expectations & values | (c) Off campus discrimination |

| (c) Importance of making friends with English students | (b) Difficulty taking part in leisure activities |

Appendix C. Example of One Interview Coded Transcript (Participant 3)

References

- HESA (Higher Education Statistical Agency). Headline Statistics. Available online: http://www.hesa.ac.uk (accessed on 1 October 2012).

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The ecology of cognitive development: Research models and fugitive findings. In Development in Context: Acting and Thinking in Specific Environments; Cornell University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 3–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, S.; Bruce, H. The stress of the transition to university: A longitudinal study of psychological disturbance, absent-mindedness and vulnerability to homesickness. Br. J. Psychol. 1987, 78, 425–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leese, M. Bridging the gap: Supporting student transitions into higher education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2010, 34, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, H.; Anthony, C. Mind the gap: Are students prepared for higher education? J. Furth. High. Educ. 2003, 27, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.; Janet, L. Do Expectations Meet Reality? A survey of changes in first-year student opinion. J. Furth. High. Educ. 1999, 23, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechanova-Alampay, R.; Terry, A.B.; Neil, D.C.; Van Horn, R.K. Adjustment and strain among domestic and international student sojourners a longitudinal study. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2002, 23, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.S. International students in English-speaking universities: Adjustment factors. J. Res. Int. Educ. 2006, 5, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.C. Tips for international students’ success and adjustment. Int. Stud. Exp. J. 2014, 2, 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Collings, R.; Swanson, V.; Watkins, R. Peer mentoring during the transition to university: Assessing the usage of a formal scheme within the UK. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 1995–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.W. Mentoring ethnic minority, pre-doctoral students: An analysis of key mentor practices. Mentor. Tutor. Partnersh. Learn. 2008, 16, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R. Mapping Educational Tourists’ Experience in the UK: Understanding international students. Third World Q. 2008, 29, 1003–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, D.L.; Reid, K.; Baumfield, V. Beyond the amusement, puzzlement and challenges: An enquiry into international students’ academic acculturation. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 41, 2198–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Gert, J.H.; Michael, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; McGraw-Hill: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L. An international graduate student’s ESL learning experience beyond the classroom. TESL Can. J. 2012, 29, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkin, K. The adaptation of East Asian masters students to western norms of critical thinking and argumentation in the UK. Intercult. Educ. 2008, 19, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyrazli, S.; Philip, R.K.; Adria, B.; Al-Timimi, N. Social support and demographic correlates of acculturative stress in international students. J. Coll. Couns. 2004, 7, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, P.B. Counseling international students. Couns. Psychol. 1991, 19, 10–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.J.; Mayuko, I. International students’ reported English fluency, social support satisfaction, and social connectedness as predictors of acculturative stress. Couns. Psychol. Q. 2003, 16, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, M.G.; Okazaki, S.; Utsey, S.O. Self-concealment, social self-efficacy, acculturative stress, and depression in African, Asian, and Latin American international college students. Am. J. Orthopsychiat. 2004, 74, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCullough, J. Asian foreign students in japan—A look at their problems and views. J. Inst. Asian Stud. 1988, 15, 141–160. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-H. The Relationship of Racial Identity, Psychological Adjustment, and Social Capital, and Their Effects on Academic Outcomes of Taiwanese Aboriginal Five-Year Junior College Students; ProQuest: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Denicolo, P.; Pope, M. Adults learning—Teachers thinking. In Insights into Teachers’ Thinking and Practice; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 1990; pp. 155–169. [Google Scholar]

- Goodson, I.F.; Sikes, P.J. Life History Research in Educational Settings: Learning from Lives; Open University Press: Milton Keynes, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Adriansen, H.K. Timeline interviews: A tool for conducting life history research. Qual. Stud. 2012, 3, 40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.A.; Byrne, D. Social Psychology: With Research Navigator. In International, with Research Navigator; Pearson/Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA; London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cabaroglu, N.; Denicolo, P.M. Exploring student teacher belief development: An alternative constructivist technique, snake interviews, exemplified and evaluated. Pers. Constr. Theory Pract. 2008, 5, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyrazli, S.; Grahame, K.M. Barriers to adjustment: Needs of international students within a semi-urban campus community. J. Instr. Psychol. 2007, 34, 28–46. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera, M. Models of social support and life stress: Beyond the buffering hypothesis. In Life Events and Psychological Functioning: Theoretical and Methodological Issues; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988; pp. 211–236. [Google Scholar]

- Ikeguchi, C. Internationalization of Education & Culture Adjustment. The Case of Chinese Students in Japan. Intercult. Commun. Stud. 2012, 21, 170–184. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, C.; Gansneder, B. An assessment of class participation by international graduate students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 1995, 36, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Sawir, E.; Marginson, S.; Forbes-Mewett, H.; Nyland, C.; Ramia, G. International student security and English language proficiency. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2012, 16, 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, S.T. International Students: Culture Shock and Adaptation to the US Culture; Eastern Michigan University: Ypsilanti, MI, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L. The role of food in the adjustment journey of international students. In The New Cultures of Food: Marketing Opportunities from Ethnic, Religious, and Cultural Diversity; Gower: London, UK, 2009; pp. 37–53. [Google Scholar]

- Locher, J.L.; Yoels, W.C.; Maurer, D.; Van Ells, J. Comfort foods: An exploratory journey into the social and emotional significance of food. Food Foodways 2005, 13, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.K.-K. Are the Learning Styles of Asian International Students Culturally or Contextually Based? Int. Educ. J. 2004, 4, 154–166. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P.-M.; Terlouw, C.; Pilot, A. Culturally appropriate pedagogy: The case of group learning in a Confucian Heritage Culture context. Intercult. Educ. 2006, 17, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Country of Origin |

|---|---|

| Participant 1 (P1) | India |

| Participant 2 (P2) | Bulgaria |

| Participant 3 (P3) | South Korea |

| Participant 4 (P4) | Bangladesh |

| Participant 5 (P5) | Nepal |

| Participant | Country of Origin |

|---|---|

| Participant 1 (P1) | India |

| Participant 2 (P2) | Bulgaria |

| Participant 3 (P3) | South Korea |

| Participant 4 (P4) | Bangladesh |

| Participant 5 (P5) | Nepal |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taylor, G.; Ali, N. Learning and Living Overseas: Exploring Factors that Influence Meaningful Learning and Assimilation: How International Students Adjust to Studying in the UK from a Socio-Cultural Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2017, 7, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7010035

Taylor G, Ali N. Learning and Living Overseas: Exploring Factors that Influence Meaningful Learning and Assimilation: How International Students Adjust to Studying in the UK from a Socio-Cultural Perspective. Education Sciences. 2017; 7(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaylor, Georgia, and Nadia Ali. 2017. "Learning and Living Overseas: Exploring Factors that Influence Meaningful Learning and Assimilation: How International Students Adjust to Studying in the UK from a Socio-Cultural Perspective" Education Sciences 7, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7010035

APA StyleTaylor, G., & Ali, N. (2017). Learning and Living Overseas: Exploring Factors that Influence Meaningful Learning and Assimilation: How International Students Adjust to Studying in the UK from a Socio-Cultural Perspective. Education Sciences, 7(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci7010035