1. Is School Improvement Innovative?

According to research on the subject, educational leadership practice can make or break a school [

1]. This being the case, it should at the very least include acts or processes that introduce new ideas or methods, therefore making the educational experience better for all involved. In other words, the leadership should be innovative in nature. Educational leadership should also be responsive enough to change with socio-historical contexts and circumstances to reflect the best knowledge about what works in as many educational configurations as possible. In keeping with demographic shifts and complexities amongst populations in the United States (US) and similar countries contributing to increased levels of cultural, ethnic, and linguistic diversity; leadership practices should be culturally sustaining [

2,

3]. As such, these practices should push the boundaries of the status quo leadership practice and further develop existing culturally responsive practices in education so these ways of leading begin to rely upon, support, and reflect local, regional and global contexts. A shift in leadership in this direction would certainly be a new idea and method, and as a result, signal innovation.

With these ideas in mind, where is the evidence for culturally sustaining innovation in educational leadership? These practices in educational contexts are as traditional as ever, according to experts in the field [

1,

4]. In the United States (US), for example, we have come to rely on improving academic achievement by closing various gaps and decreasing dropout rates for students ‘at risk’, who happen to be disproportionately poor and more often than not, brown or black students of color. This deficit-based focus on correcting negative attributes of culturally and linguistically diverse students as ‘school reform’ and novel responses to ‘educational change’ [

5] is not inspired by strength-based research on inclusive or successful measures proven to be effective for all students [

6]. However, despite the dearth of innovation in educational leadership approaches, some gains are being made. Today’s schools strive for safe school environments, increased parent and community involvement, more trust with teachers and community, the provision of instructional support, respect of school socio-cultural and socio-political contexts, with deliberations about who and how we hire to support and retain personnel. These actions include the appropriate prioritization of goals, distributed leadership, use of data, development of people, and resources allocated that align to improvements identified by school community members [

7,

8,

9].

The ‘at risk’ students who are intended to benefit from leadership for ‘school improvement’ are often disadvantaged, underserved, excluded or marginalized when compared with White and often mainstream peers with regard to schooling experiences in the US. Sadly, the innovations we employ to support ‘at risk’ students have become business as usual. If leadership for ‘school improvement’ is an effective innovation as surmised by researchers in the field [

10,

11,

12], why do academic disparities remain a constant in our educational landscape? School improvement measures, initiatives, and programs are beneficial, but are they good enough to effect real and substantive change toward improvement? Now might be the time for scholars, researchers, and practitioners to consider innovation in educational leadership to benefit larger numbers of more diverse students.

In this article, we interrupt the mainstream dominant discourse on educational leadership by offering a novel and additive approach to educational leadership in diverse school contexts. Three types of school leaders are described on a continuum of efficacy as well as examples of innovative culturally sustaining leadership practices. We provide implications for educational leaders and policy makers and conclude with a brief discussion on the prospect for maintaining culturally sustaining educational leadership in the future.

2. A Continuum of Culturally Sustaining School Leaders

What kinds of leaders serve students and communities in predominantly diverse (e.g., culturally, linguistically, ethnically, racially, social class) school contexts? Research suggests that many leaders aim to be culturally responsive and believe that they are moving toward culturally sustaining leadership in some way [

1,

4].

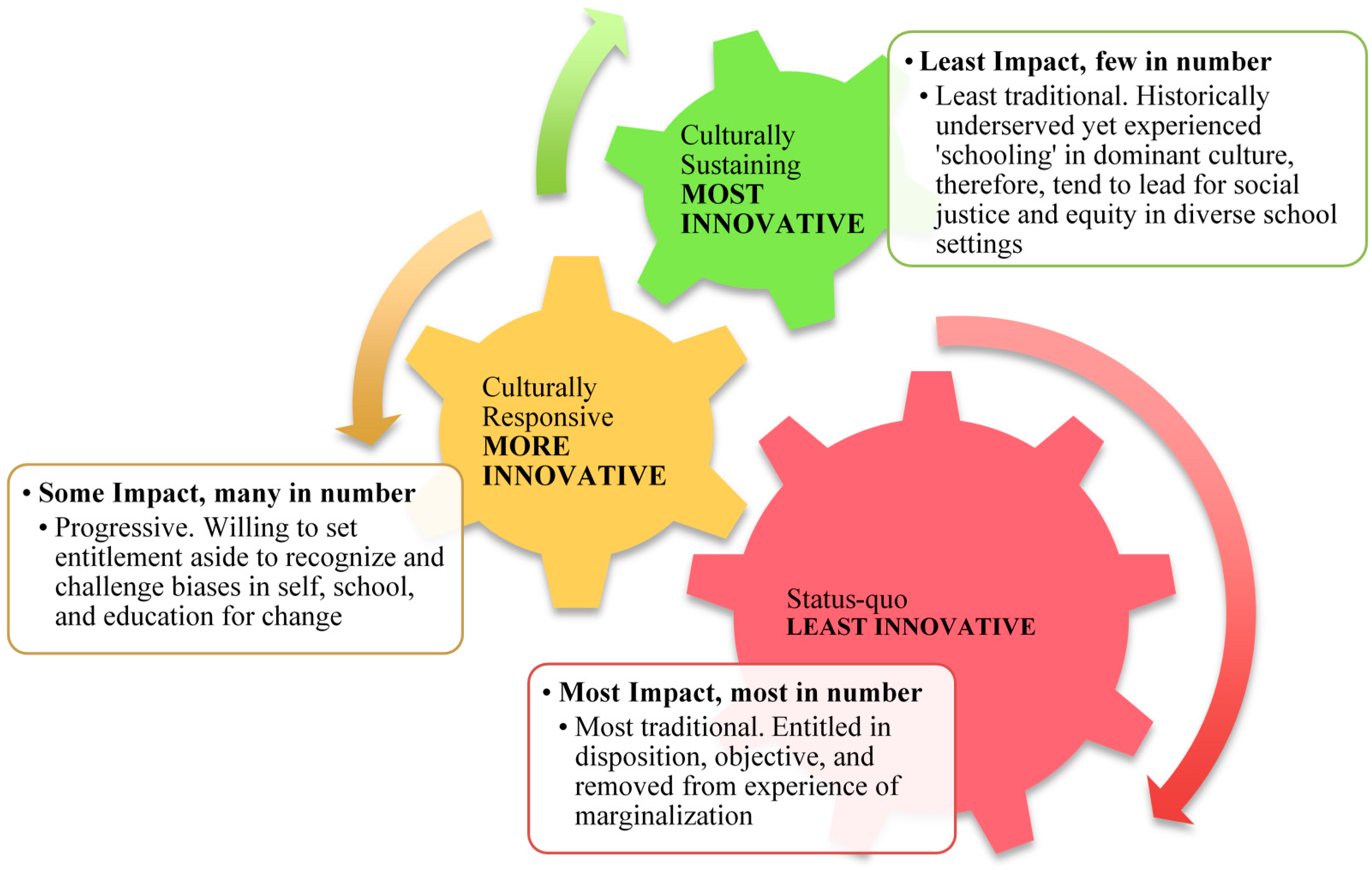

Figure 1 reveals that most also work simultaneously towards school improvement. Increasing overall student achievement and reducing dropout rates are the kinds of goals shared by many educational leaders, however levels of innovative leadership practice beyond these and similar efforts vary depending on the leader.

The wheels for depicting a continuum of leadership practice toward culturally sustaining leadership function as interactive gears, impacting educational outcomes for all students. The direction and speed at which each wheel rotates differs based on the intention and/or manifestation by which leaders engage in addressing issues related to educational inequities for the students they serve. A shift toward more culturally sustaining leadership practice requires the smallest of the three wheels to dictate the direction and speed of the entire system. As it stands, research suggests that the least traditional and potentially most innovative leaders tend to have the lowest overall physical presence in schools [

13,

14,

15]. These leaders are often leaders of color and as such are disproportionately represented in formal leadership positions, as evidenced by research on recruitment and attrition of leaders of color [

14,

15]. As the figure suggests, in contrast, the most traditional leaders are greater in number and more representative of mainstream society demographics [

1,

4,

16]. In fact, the majority of educational leaders in the US are not culturally and linguistically diverse. Comparatively and as a result, there are more leaders representing mainstream demographics, values, and leadership practices which consequently have the most impact on what is happening in education today [

9,

17]. On the other hand, progressive leaders, who have much promise for impacting educational change given their numbers and degree of critical consciousness, represent the center of the culturally sustaining leadership continuum [

18,

19].

Though likely least innovative, the majority of leaders representing more traditional forms of what can be considered the status quo practice are highly moral and ethical, claiming to lead in a manner that transcends difference [

1,

4]. For these often self-proclaimed color-blind leaders, data is a driver, difference holds no consequence, and all students are treated equally. Corporate-style leadership, grounded in business models and empirical best evidence syntheses, are regarded as the best solutions to low student achievement, dropout rates, and lack of parent engagement [

8,

9]. Values of integrity, transparency and fairness commonly characterize this group. For many of these leaders, focusing on diversity and difference is a distraction and so difference is often ignored. For them, singling out students or groups based on difference is highly undesirable. A better way to deal with diversity is to consider all learners, teachers, and their families as the same, avoiding favoritism or undue focus on particular subgroups. Even though some of these leaders distribute leadership and can be considered transformational, these are the most traditional and therefore least innovative of leaders exhibiting culturally sustaining practice [

17].

Progressive culturally responsive educational leaders, similarly, represent mainstream dominant, cultural and educational ideologies (e.g., data driven, increase student achievement, decrease dropout rates); however, these leaders critically recognize educational inequities as a detriment to the local and global greater good. Leaders in this subgroup sometimes choose to race themselves outside of Whiteness [

20], although underserved communities often consider them White allies. These leaders deliberately

choose to withhold or set aside unearned privileges and entitlements to work alongside or on the behalf of underserved communities of teachers, learners, and families. They lead with a sense of responsibility and purpose in using their access, knowledge, education and spheres of influence to ‘level’ the educational playing field [

21,

22,

23,

24]. These leaders are innovative in that they challenge their own and others’ assumptions about leadership, teaching and learning; beginning with themselves and moving out into their schools and communities with transformative change as their ultimate goal. This second group of leaders are deliberate about purposefully taking up and practicing leadership through critical lenses of race, ethnicity, gender and/or difference in order to interrupt and confront the status quo power and dominance while grappling with the challenges of working through cultural, linguistic and other differences in K-12 schools. According to research on more critical and transformative leaders, their numbers are few but growing, as leaders grapple with diversity in various and increasingly diverse educational contexts [

18].

The third type of educational leader in this model tends to embody cultural sustainability throughout their practice as a result of their lived experiences with systemic or educational marginalization or exclusion. These include those from historically underserved backgrounds (e.g., in the United States of African-American, Latina/o, American Indian, Indigenous, etc. descent, or from lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, or intersex (LGBTQI) communities) who have experienced or overcome personal, societal, and institutional inequities in the past and present. These leaders are often cross-cultural, bicultural or multicultural; meaning their identities intersect critical categories of ethnicity, race, class, gender and language. Leaders in this third category are not usually members of dominant societies in their countries of residence, although some choose to race themselves outside of Whiteness and assume the lenses of the systemically underserved or ‘minoritized’ populations they serve [

23,

24,

25]. As a result, these leaders often encounter racism, discrimination, classism and other micro aggressions or oppressions regularly as part of their participation in societies where they are often historically marginalized. In many cases, these leaders have attained degrees in higher education, leadership preparation/credentials and school leadership positions despite a myriad of odds [

19,

21,

22].

As a consequence of the disproportionate numbers of educational leaders of color as compared to the diversity present in schools in the US and similar countries, these leaders have little physical presence in schools. They are underrepresented in educational leadership positions at every level across the Nation, particularly women of color, American Indians, and Latina/os [

14,

15,

23,

26]. These educational leaders have past, recent or current experiences that associate the attainment of education with a viable means of breaking cycles of poverty, exclusion, and marginalization. As a result, these leaders tend to be creative with unrealized potential for innovation in their leadership practice for social justice and educational equity for underserved constituents as well as all learners [

21,

23,

24,

25,

26]. Since these leaders are underrepresented in educational leadership positions in predominantly White educational institutions and contexts in the US and world, their culturally sustaining leadership practices are largely unknown, untried and, currently, have had little impact on achieving equity in diverse contexts as they are currently known.

3. Core Characteristics of Culturally Sustaining School Leaders

Emergent research on the practice of culturally sustaining leaders in diverse school settings suggests critically conscious leaders work with social justice and equity at the forefront of their practice [

10,

11]. These leaders tend to:

“Read” the world and act accordingly through lenses that are critically focused toward action addressing inequities in schools based on ethnicity, race, gender and class;

- ○

For example, serving on school boards or committees examining core curriculum for cultural relevance, sustainability, or and saliency.

Engage staff, parents, community members and students as appropriate in conversations about how the roles ethnicity, race, gender and class play out in education;

Work to build and maintain trustful relationships with individuals in their teaching, leading and learning communities who are from different backgrounds or experiences;

Be seen leading by example, actively engaging in education in the classrooms with teachers, students, parents and community members, rather than being locked away in an office;

Work directly with community members, inviting and bringing them into the school to participate and engage in the schooling process, thus honoring the community as their constituents;

Bring staff, teachers, parents, and peers to consensus by prioritizing shared goals and establishing common ground throughout decision-making;

Be aware of their own marginalization or privilege and the ways in which their positionality and identity impact their leadership practice; and,

Show evidence of being present active servant leaders, leading for change and transformation as a higher calling or for the greater good.

It can be surmised that the distance between traditional status quo forms of leadership and more innovative, critically conscious leadership can be measured by the degree to which leaders promote, facilitate and sustain inclusivity throughout all aspects of their practice. Beyond bringing diverse (e.g., race, ethnicity, linguistic, sexual orientation, class) perspectives into the practice of leadership, representative of the communities served by schools locally, nationally and globally; culturally sustaining leadership requires greater attention and appropriate critical action toward naming challenges associated with equity and diversity for the groups of the communities impacted. Culturally sustaining leaders critically think about issues of access and equity by analyzing why things are the way they are, and how they can be remedied, and by adding innovation or change through action that will reverse or eradicate identified inequities toward overall improvement for all learners involved [

23,

27]. The kind of innovation described here, is not change for the sake of change, but change to benefit the greater good. These leaders demonstrate the inherent strength in diversity [

21,

26] rather than then the assumed challenge described by others [

28]. Just as the wheels for the types of leaders in

Figure 1 function as interactive gears impacting educational outcomes for the students in our schools; culturally sustaining leadership needs to continually cycle through until innovation and increased equity become closer to the norm, power and influence are redistributed, and diversity is considered a solution rather than a challenge in education.

4. Examples of Innovative Culturally Sustaining Leadership

These exemplars are drawn from a few largely qualitative research studies conducted between 2011 and 2015 featuring culturally sustaining leaders in culturally and linguistically contexts in the US and New Zealand [

23,

24,

25]. The total number of leaders is 70 working in as many educational settings. There is an equal distribution of women and men with most of the leaders being culturally and linguistically diverse (e.g., Māori, Pacific Islander, African American, Latina/o, of European descent). The contexts include early childhood education centers, primary schools, intermediate, secondary and some higher education centers. Data includes surveys, interviews, and observation. Analysis was mainly constant comparative or phenomenological [

29].

The research surveyed suggested that when leaders who are culturally sustaining in their practice address mainstream educational initiatives, they do so

for and with the learning community and local context in which they are situated through the critical lenses of ethnicity, race, culture, class and gender. Building on this premise, when culturally sustaining leaders think about establishing a safe school environment, research findings reveal that they go beyond the community service officer (CSO) idea embraced by most schools [

30]. They tend to have CSOs but also may bring in programs to confront bullying or inform and complement LGBTQI support for students and families. For culturally sustaining leaders, attention to parent and community involvement means making concerted efforts to know their students’ families and neighborhoods. They focus on accessibility, having an open door policy with parents, being visible and available, and extend purposeful invitations to express value for parent and community perspectives in the goings on of the school. Leaders who are culturally sustaining provide professional development and instructional support for teachers and staff that include and reflect the languages and cultures of the community and that have proven successful in lifting the academic achievement and well-being of all students being served. As previously indicated, culturally sustaining leaders work diligently to establish trust with teachers and community members, particularly when they are from underserved or underrepresented ethnic or cultural groups. It is important for these leaders to establish and maintain trust if leadership is to be shared or distributed appropriately.

As a result of working with or on behalf of marginalized students, families and communities, culturally sustaining leaders work hard to understand and respect their schools’ socio-cultural and socio-political context, which can serve as a critical resource for enacting transformational change. These leaders are aware of disproportionality in education and the mismatches between teachers and students. Culturally sustaining leaders bring this knowledge and attention into the practice of personnel hiring, support and retention. To this end, research findings suggest that they actively recruit and mentor aspiring leaders from underserved backgrounds or those who choose to carry innovative dispositions for social justice and educational equity. These leaders restructure the school so that activities associated with teaching, learning and schooling, in general, are aligned with identified priorities that include equity. Culturally sustaining leaders distribute power and influence appropriately for mutual responsibility. Therefore, the entire learning community can share ownership of challenges and successes. These leaders are competent in understanding or have the ability to learn how to collect and interpret data when leading innovative change, as well as how to teach staff, teachers, and families data literacy to inform and foster school success. Along these lines, they focus on building capacity in their teams by including and empowering parents and community members in order to strengthen the core of the school culture. Finally, they align and allocate human, material and fiscal resources to the overarching school goals, guiding new practices and ways of leading, ergo innovation.

5. Implications toward Increased Culturally Sustaining Leadership

It seems that in the face of educational and achievement inequities and increased diversity in the US and similar countries, we should consider innovative approaches to school leadership. There are systems and groups of people in place who can serve to usher in a new era of culturally sustaining educational leadership. This work must take place on many levels at once, ranging from individual to local, regional, national and global if we are to see substantive and sustainable change.

The first group are university personnel who work with school leaders. Culturally sustaining pedagogy and multicultural education have been part of the teacher-training lexicon for more than three decades. These classroom-based pedagogical interventions have impacted teacher education in many counties. Academics who partner with schools can share current research on leadership for social justice and emergent research on culturally sustaining leadership with school leaders who are challenged with ways in which to handle achievement gaps and limited school success with particular subgroups. Scholars can further encourage school leaders to recruit, hire, mentor and support teachers from diverse backgrounds with a wide range of experiences to complement the diversity reflected in their schools. School leaders may need to be encouraged to mentor novice and younger teachers who may lack technical experience, but who possess culturally sustaining potential and have, themselves, ‘made it’ through the ‘system’.

Current school district and Ministry leaders who lead just outside of school settings and are responsible for hiring school site leaders need to work closely with university preparation programs that provide authentic leadership courses and fieldwork, promoting a social justice and equity agenda to address issues related to diversity and inclusivity. This level of leadership needs to think beyond the present and into the future of who learners and their needs will be in the next 5 years and beyond. How do we need to begin to shift current systems of school practice so that we are prepared to lead our community of learners of tomorrow?

Technological, economic, geographic, social and educational realities are shifting and they will continue to do so at an ever-increasing rate. Culturally sustaining leadership today may morph into complexity sustaining leadership within the next few years. Educational leaders beyond school leadership will be wise to think about creating leadership training models for aspiring leaders in partnership with universities that focus on recruiting reform-oriented leaders of every background in order to access and impact every type of learner. The curriculum for these leadership development programs should be context specific and begin by improving student achievement and reducing drop-out rates as the bare minimum—with a clear focus on reflective and democratic leadership as well as leadership for social justice and educational equity that challenges leaders to come to terms with their own biases, dispositions and beliefs about themselves and others prior to their work in schools and communities [

23,

31,

32].

Finally, policy makers at every level of the government concerned with education are implicated if we are to witness an increase in culturally sustaining leadership. First, we need to realize that individual people write policy and that government is run by groups of individuals as well. We maintain that culturally sustaining leadership equally begins with individuals who come to realize that educational inequity and diversity are inextricably tied to poverty, marginalization and oppression in the US and similar countries. These individuals further realize that if anything is to be done to interrupt the status quo of achievement disparities and cycles of poverty, they need to take it upon themselves to choose to incite change. When enough individual policy makers, scholars and school and district leaders realize culturally sustaining leadership is the innovation we need to turn schools around; we may see incentives to study its effectiveness and to recruit, hire, mentor and maintain a more diverse cadre of educational leaders. Then and only then will we begin to see the power of having educational leaders focused on equity, reform and change.