Mapping the Complexities of Effective Leadership for Social Justice Praxis in Urban Auckland Primary Schools

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the characteristics and behaviours of effective leadership for social justice and equity for academic achievement?

- (2)

- How do effective leaders for social justice and equity lead in schools with highly diverse student population in urban Auckland primary schools?

1.1. Effective Leadership

1.2. Effective Leadership for Social Justice and Equity

Successful leaders in schools serving highly diverse student populations enact practices to promote school quality, equity and social justice through: building powerful forms of teaching and learning; creating strong communities in school; nurturing the development of educational cultures in families; expanding the amount of students’ social capital valued by the schools.[12] (p. 372)

1.3. Improved Outcomes for all Students

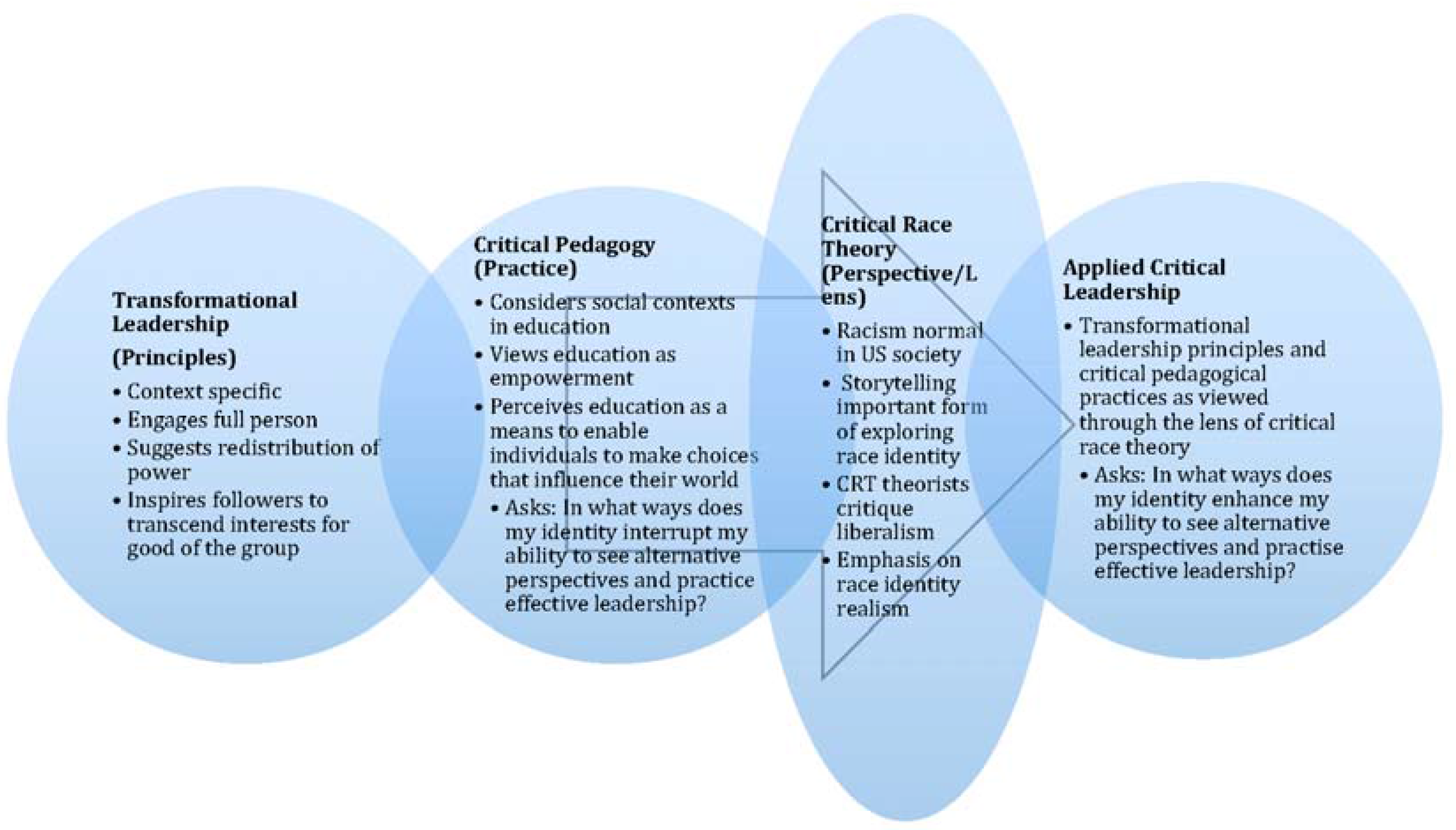

1.4. Theoretical Framework—Applied Critical Leadership

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Research Design and Rationale

2.2. Setting and Participants

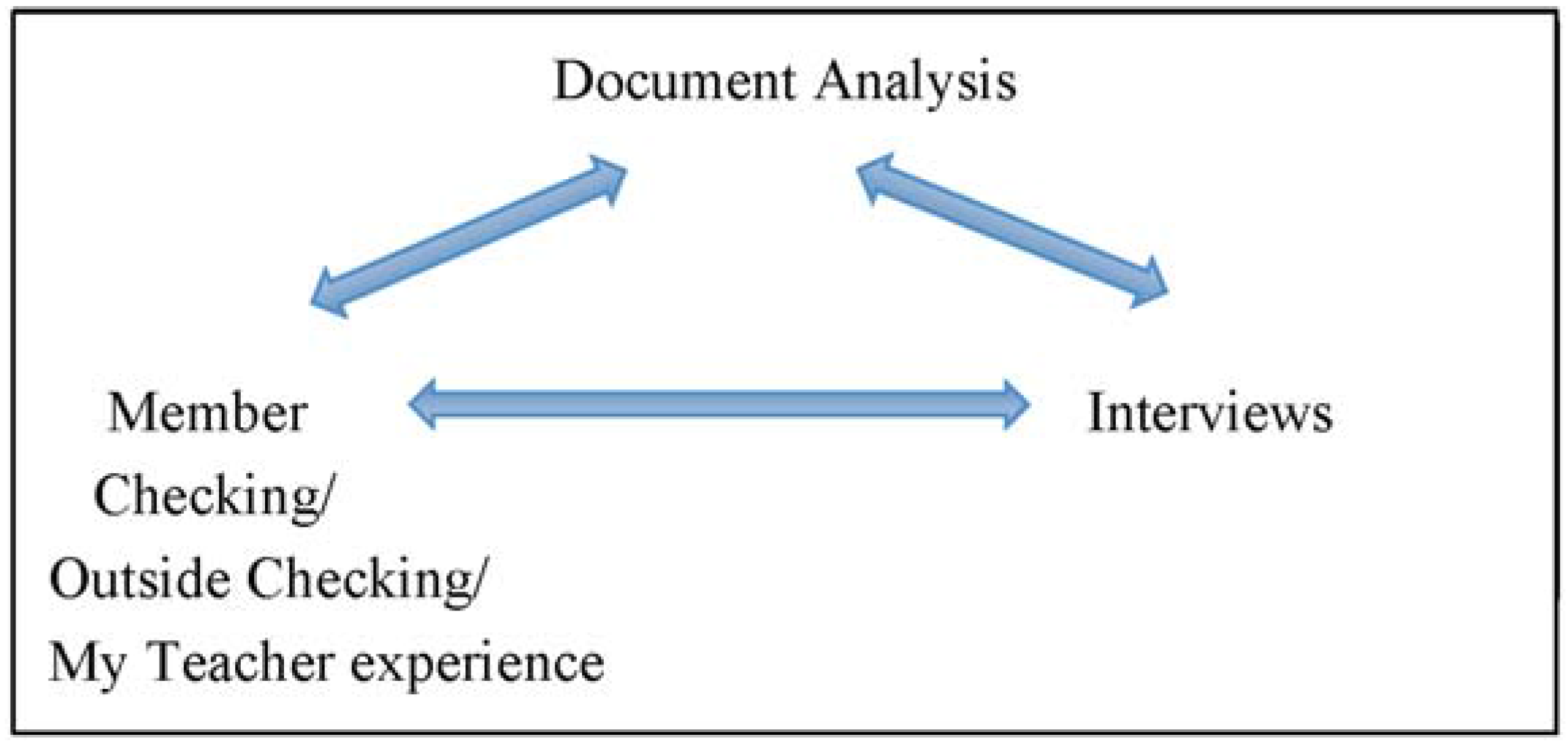

2.3. Methods

2.4. Data Collection

2.5. Data Sources

2.6. Interviews

2.7. Document Analysis

3. Results

3.1. ACL Characteristic 1: Self-Awareness

I am aware of it. I’ve probably been influenced by my mum, in that “considering everybody”, that part. I am aware of marginalising people and trying to think about how they can feel part of our place … I have attended … women in educational leadership papers [courses], probably people who made me think in a way or about my behaviours. So before, the behaviours were there possibly and I hadn’t thought about them.

As I’ve got older I have been, I guess, made more aware that your identity, your cultural identity is very much linked to who you are, where you are from and the values of the place you grow up in and things like that. So more and more as I’ve gone along I have become explicit… it’s grown, you know that sense of identity.

I was a middle class woman, Pākehā [Caucasian], New Zealander, very little awareness of Māori in terms of when I was at school… I lived in the North Island of New Zealand, which has more contact with Māori and Māori in major cities than in the South Island but yet I was still very provincial in my understanding.

I wanted to have more understanding of things … you learn so much from the past and that knowledge you carry forward.

I suppose one of the advantages I have is that coming from such a mixed pathway … I am a fighter for social justice. Part of that was because I open my eyes to see things differently and wasn’t going to just accept what people accepted as normal … I think the advantage of somebody that comes from a different pathway into this, is that I have a real sense of—I know what life is like and I know what the education system is capable of in terms of putting individuals or groups of people in boxes and saying that’s where you belong.

3.2. ACL Characteristic 2: Moral Purpose—Values and Belief System (Align with ACL CRT lens)

Key thing about behaviour of effective leaders is, it’s easy to say but they actually do walk the talk, and you actually show what you value by what you do, and when you do it, and how you do it, and how you make what you do explicit.

I am a Māori principal. I am not a principal who happens to be Māori. So the way that I am, everything I am influences the way that I lead, and the way that I work, and the way that I impact, and my expectations.

I suppose that it’s hard to separate characteristics and behaviours from values. Values of manaaki: which is to care for, nurture, embrace kind of, to look after, to care to. Aki: to lift the mana of others and so that everything that you are doing is looking at the individual’s mana and dignity, so that those things are always there—being truthful, being a role model, walking the talk, being somebody who is themselves honest and open and is just true to who they are … particularly when you are dealing with diverse communities and you are dealing with a community where the majority of people have been not necessarily well catered by a system.

3.3. Characteristic 3: Trust at All Levels

I think the first thing is trust. The trust between everyone in the culture of the school, trusting for each other to fulfill our roles but having the trust between each of us with confidentiality of what happens within the school and trusting that. Yeah, I think trust is the biggest thing, the gel that holds everything together.

The trust of the parents, having them on board within the culture of the school, involving them in things we do. Trusting the children, just as trust with the parents, because we have a big thing about having them around us for about five hours a day. So I believe trust is something that makes the school.

One of the things when they come to school is parents hide their ethnicity and their culture because they want to learn English. Some don’t acknowledge it. We get funding, we get good funding for English as second language learners. So we want to get as much money as we can because we can put programmes in place. We have good programmes to help children learn English. So we have to get over this barrier where parents don’t want to shut the door on their culture.

3.4. ACL Characteristic 4: Courageous Conversations

The whole thing about a courageous conversation is actually about, if you keep linking everything back to what’s best for the students, why you are having the conversations, if you see something is not going to be impacting not so well on students? So always the basis is why are you having the conversation? If the moral purpose is right, then it’s fine to have it. Then it’s about not making assumptions, that’s actually being really strongly evidence-based, and making sure you do have as much information as you can, and you are not jumping to conclusions or you are really understanding what it is that is happening to cause this dilemma.

If you don’t allow them [teachers] a chance to grow, you are going to have a stagnant lot. So in these conversations you have, you’ve got to allow them to grow, not impinge your views or to tell them this is got to be done … but you might say, what do you think of this? Let them think about it.

It’s been predominantly staff and sometimes students and we’ve sometimes had kids upset. So I went through a review process, by creating systems and … processes and articulating that to people. Then they know the methods or the ways of putting things together, that I do listen. So this is my way of response—I am going to investigate or find out about it, and we’ll go through this process … So all these are requiring us to have tricky conversations, but we are trying to keep it in the positive and steer it forward.

3.5. ACL Characteristic 5: Group Consensus

So we don’t make decisions by vote, we make decisions by consensus. That, to me, means it’s about a learning community because if you need more information before you can make a decision that supports something, that is about social justice or equity or equality, then if you need more information, then that is what we do.

School vision and core values are to pull down into every layer of the school then you can’t do it quickly. It’s not a quick thing! You can do it quickly at a superficial level but how we do things here is much more. It takes longer to establish, and it takes longer to establish at the different levels of the school, but again they are quite deliberate acts of how that plays out.

3.6. ACL Characteristic 6: Transformational Leadership

What you do and how you deliver and how you say things, is also modelling all the time for people what you perhaps want to see others do. So you are constantly having very deliberate acts of leadership every day. It’s not casual. It looks casual, but it’s really purposeful.

I will ask their opinion rather than I make a decision. I kind of check maybe what is the current feeling and I will then decide actually is this what we want or other people might say, “actually, have you thought of this?”

So there’s lots of things like consultation, collaboration, it’s time and patience, and not being too rigid and saying “this is the way it has to be” or saying you don’t know or “this is what I think, [but] what do you think?”

So what I am doing is working with a coalition of the willing who want to be able to do it … but are a bit scared. So I am taking their hand. It’s like they are in the dark and I’ve put my hand out, to grasp the hand and they are letting me lead. When you’ve got credibility because you’ve done it, that’s a powerful tool. I guess the thing is walking with those people that want to be led to change their thinking and their hearts and minds.

I am in a position of influence and power but you know my belief is if you share power it is multiplied, rather than it’s halved. People hold onto the sense of power because I want this now but actually, share it, it’s then multiplied.

When anyone gets a promotion, we all take a collective pride and pleasure in [that]. Last year we had two of our aspiring principals get jobs. This year we had three. I guess that is part of the whole collective input, that we have growing leaders.

We believe in inclusiveness; that everyone has a chance to learn maybe at a teaching level or at a student level or even bringing people in to help us out ourselves. To be better at something that we can do or to increase our ability by doing our own learning and calling out to others if we want to, so that everyone has a chance to be part of the learning situation.

3.7. ACL Characteristic 7: Creating a Socially Just Environment through Social Responsibility

Social justice is about connection to social organisation and social grouping and about the commonalities of what we need to survive and live on this earth and live together in communities. So social justice is about how we as people work together, so no one is dictating or managing resources or the dominance of a culture or a custom or one particular thing pertaining to another community or society. So social justice is where there’s a system of allowing people the right and access to and responsibility to be part of the organisationand therefore know that they are duly heard and responded to and outcomes happen. That they haven’t be slighted, that they can actually have a system where the society that will honour that, that’s the agreement.

Equity and about making education and making learning work for every student. So part of that is pushing teachers’ thinking past the definition or the way they might interpret their role as a teacher, to a person who is in that child’s life for a year and who needs to do whatever it takes to make it work.

The right of all to fairness, the right to be, the right to make choices, the right to have access to knowledge, power and influence, vision making, to have a voice, to be agents for their own determination. That the system isn’t socially just because it advantages particular groups in society, part of the role for social justice is challenging that.I suppose for me, if I think about social justice it’s about looking at the world and seeing what is unjust, then working to make it just. So that giving voice to everybody, so that it’s not just the world is created just for some people.

I read something the other day about “fair”. It’s got to be fair! And I thought, well it actually isn’t. It’s got to be unfair at times just to give other people a step up. It’s never going to be the same, it’s not about being all equal, it’s about who needs an extra hand at a particular time and just acknowledging difference, so that the difference isn’t the problem.

3.8. ACL Characteristics 8: Transcending Interests for the Greater Good—The Student

So some of the items around the e-asTTle test this time haven’t been relevant because they haven’t been changed into metrics and I was asked to do something in yards. So that item I got wrong, but in actual fact it is not a reflection of my ability.

We test the children on PAT [Progressive Achievement Test], we report that to the Board, we report that to the Ministry results. We realised that our ESOL [English for Speakers of Other Languages], children make them dive, that’s only because everything is written in English.

In our school every teacher has to be good at teaching ESOL kids, so part of the skill set here is not just being an EFL [English as a Foreign Language] teacher, it’s not just about knowing blended language and digital technology. They actually need to know how students acquire language, specifically how to support students on how to develop oral language, to develop English on the English language progressions and everyone has to know that. That links back to what’s best for the child. At the end of the day it has to come back to that.So I expect teachers to work really hard to develop in-depth knowledge of every student’s context.

What needs to happen in this country in terms of changing the system itself to respond to the needs of the diverse communities, it’s not going to happen by more reading, writing and maths and professional development. It’s going to change through changing relationships, and in particular across cultures. So that means we can’t walk on our own to find the solutions, we have to walk together to do it.

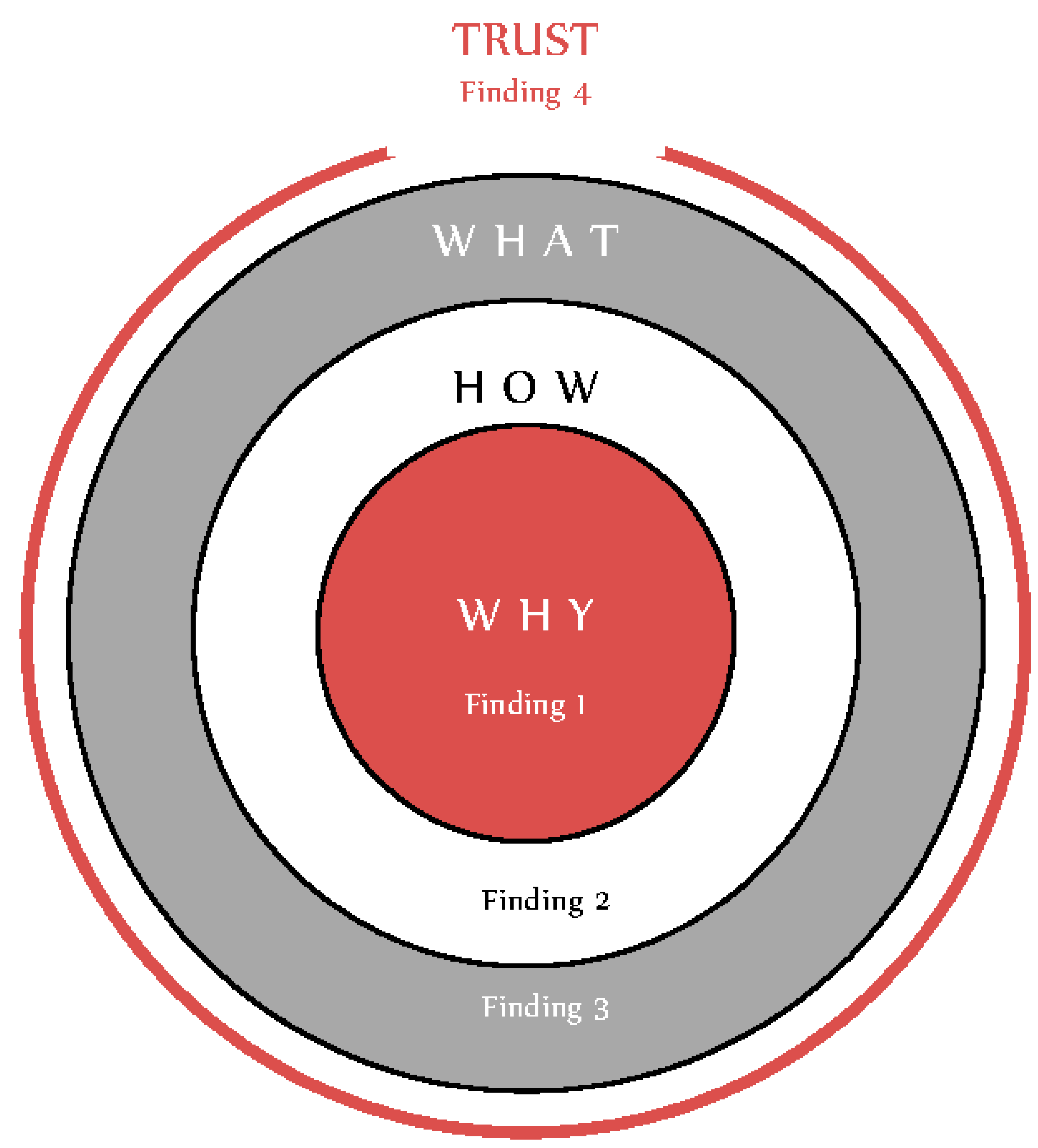

4. Discussions

- Finding 1: Leaders’ self-awareness transpires into altering mindsets. Includes axiological philosophy, vision and passions that form the “why” of the model;

- Finding 2: Leaders demonstrate transformational leadership behaviours to influence others. Includes how values and beliefs inform behaviours, and collaborative practices form the “how”;

- Finding 3: Leaders raising student academic outcomes through alternate avenues. Includes social capital, and community outcomes form the “what”;

- Finding 4: Leaders building and establishing trust as the foundational principle of characteristics, behaviours and student outcomes.

4.1. Finding 1: Leaders Self-Awareness Transpired into Altering Mindsets (Include Axiological Philosophy, Vision and Passions form the “Why”)

4.2. Finding 2: Leaders Demonstrated Transformational Leadership Behaviours to Influence Others (Includes How Values and Beliefs Inform Behaviours and Collaborative Practices the “How”)

4.3. Finding 3: Leaders Raised Student Academic Outcomes through Alternate Avenues (Included Social Capital and Community Outcomes Formed the “What”)

4.4. Finding 4: Leaders Built and Established Trust, as the Foundational Principle of Characteristics, Behaviours and Student Outcomes

5. Conclusions

Qualified educational leaders with alternate experiences who can relate to their diverse communities in culture, language, and experience are greatly desired, finding strength in leaders’ identities to draw from all the while. From this alternate perspective, diverse identities and experiences are viewed as commodities rather than liabilities in regard to effective leadership practice.[20] (p. 9)

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics New Zealand. Census. Available online: http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2013-census/profile-and-summary-reports/infographic-culture-identity.aspx (accessed on 10 March 2015).

- McNaughton, S.; Lai, M.K. A model of school change for culturally and linguistically diverse students in New Zealand: A summary and evidence from systematic replication. Teach. Educ. 2009, 20, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, V. Student-Centered Leadership; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, K.M. Leadership for social justice and equity: Weaving a transformative framework and pedagogy. Educ. Adm. Q. 2004, 40, 77–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, G. Social justice leadership as praxis developing capacities through preparation programs. Educ. Adm. Q. 2012, 48, 191–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Marie, G. Leadership for social justice: An agenda for 21st century schools. In The Educational Forum; Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2008; Volume 72, pp. 340–354. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaría, L.J.; Jean-Marie, G. Cross-Cultural Dimensions of Applied, Critical, and Transformational Leadership: Women Principals Advancing Social Justice and Educational Equity. Camb. J. Educ. 2014, 44, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, C.A.; Theoharis, G.; Sebastian, J. Toward a framework for preparing leaders for social justice. J. Educ. Adm. 2006, 44, 209–224. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, C.D. Antecedents of Servant Leadership A Mixed Methods Study. J. Leader. Organ. Stud. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, E.E. Qualities for Effective Leadership: School Leaders Speak; Scarecrow Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.A.; Riehl, C. What We Know about Successful School Leadership; National College for School Leadership: Nottingham, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L.; Mulford, B. Models of successful principal leadership. Sch. Leader. Manag. 2006, 26, 371–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría, L.J. Critical Change for the Greater Good Multicultural Perceptions in Educational Leadership toward Social Justice and Equity. Educ. Adm. Q. 2013, 50, 347–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulford, W.R. Do Principals Make a Difference?-Recent Evidence and Implications. Lead. Manag. 1996, 2, 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- McCarley, T.A.; Peters, M.L.; Decman, J.M. Transformational leadership related to school climate a multi-level analysis. Educ. Manag. Adm. Lead. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, L.R. Enacting social justice: Perceptions of educational leaders. Admin. Issues J. Educ. Pract. Res. 2011, 1, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, L.A. Theoretical Foundations for Social Justice Education; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Young, I.M. Justice and the Politics of Difference; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves, A. Extending Educational Change; Kluwer Academic Publishing: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaría, L.J.; Santamaría, A.P. Applied Critical Leadership in Education: Choosing Change; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, A.; Quong, T. Valuing differences: Strategies for dealing with the tensions of educational leadership in a global society. Peabody J. Educ. 1998, 73, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, C. The Age of Paradox Cambridge; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tarabini, A. Education and poverty in the global development agenda: Emergence, evolution and consolidation. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2010, 30, 204–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theoharis, G. Social justice educational leaders and resistance: Toward a theory of social justice leadership. Educ. Adm. Q. 2007, 43, 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Education Review Office. Raising Achievement in Primary School; Crown: Wellington, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Investing in Educational Success. Available online: http://www.education.govt.nz/ministry-of-education/specific-initiatives/investing-in-educational-success/ (accessed on 10 March 2015).

- Alton-Lee, A. (Using) evidence for educational improvement. Camb. J. Educ. 2011, 41, 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, R.S. The culture builder. Educ. Leader. 2002, 59, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H.A. Theory and Resistance in Education: A Pedagogy for the Opposition; Bergin & Garvey: South Hadley, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G.J. Preparing teachers for diverse student populations: A critical race theory perspective. Rev. Res. Educ. 1999, 24, 211–247. [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B.M. Leadership and Performance beyond Expectations; Free Press: New York, NY, USA; Collier Macmillan: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, J.M. Leadership New York; Harper and Row Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S.L. Axiology—Theory of Values. Philos. Phenomenol. Res. 1971, 32, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, C. Administrative philosophy: Values and motivations in administrative life. Public Adm. 1996, 77, 439–440. [Google Scholar]

- Reinharz, S.; Bowles, G.; Duelli-Klein, R. Experiential analysis: A contribution to feminist research. In Theories of Women’s Studies; Routledge & Kegan Paul: Boston, MA, USA, 1983; pp. 162–191. [Google Scholar]

- Baloglu, N. Relations between Value-Based Leadership and Distributed Leadership: A Casual Research on School Principles’ Behaviors. Educ. Sci. Theory Pract. 2012, 12, 1375–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan, J.H.; Schumacher, S. Research in Education: Evidence-Based Inquiry; Pearson Higher Ed.: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stake, R.E. Case studies. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2000; pp. 435–454. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Drever, E. Using Semi-Structured Interviews in Small-Scale Research. A Teacher’s Guide; ERIC: Edinburgh, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Punch, K.F. The analysis of qualitative data. Introd. Soc. Res. Quant. Qual. Approaches 2005, 2, 193–233. [Google Scholar]

- White, B. Mapping Your Thesis: The Comprehensive Manual of Theory and Techniques for Masters and Doctoral Research; Australian Council for Educational Research Press: Victoria, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalist Inquiry; Sage: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Education. Education Counts. Available online: https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/series/2531 (accessed on 10 March 2015).

- Gibbs, G.R. Analysing Qualitative Data; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Weitzman, E.A. Choosing computer programs for qualitative data analysis. In Qualitative Data Analysis; Miles, M., Huberman, A., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G. Advances in the Methodology of Grounded Theory: Theoretical Sensitivity; Sociology Press: Mill Valley, CA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sinek, S. Start with Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action; Penguin Group: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- West-Burnham, J. Rethinking Educational Leadership: From Improvement to Transformation; A & C Black: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Argyris, C. Teaching Smart People How to Learn; Harvard Business School Publishing: Watertown, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K.A. The principal’s role in teacher development. In Teacher Development and Educational Change; New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, V.M.; Le Fevre, D.M. Principals’ capability in challenging conversations: The case of parental complaints. J. Educ. Adm. 2011, 49, 227–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. (Ed.) The Reflective Turn: Case Studies in and On Educational Practice; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991.

- Istance, D.; Dumont, H. Future directions for learning environments in the 21st century. In The Nature of Learning; OECD Publications: Paris, France, 2010; p. 317. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, M.; Cooper, B. Passionate and proactive: The role of the secondary principal in leading curriculum change. Waikato J. Educ. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J.P.; Halverson, R.; Diamond, J.B. Investigating school leadership practice: A distributed perspective. Educ. Res. 2001, 30, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohepa, M.K.; Robson, V.; Robinson, V. Māori and educational leadership: Tu rangatira. AlterNative 2008, 4, 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Weitzman, E.A. Choosing computer programs for qualitative data analysis. In Qualitative Data Analysis; Miles, M., Huberman, A., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wahlstrom, K.L.; Louis, K.S. How teachers experience principal leadership: The roles of professional community, trust, efficacy, and shared responsibility. Educ. Adm. Q. 2008, 44, 458–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A.; Schneider, B. Trust in Schools: A Core Resource for Improvement; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- New Zealand Principals’ Federation. Collaboration to Raise Māori Achievement. 2013. Available online: http://www.nzpf.ac.nz/?q=list/releases/2013/collaboration_to_raise_Māori_achievement-27_September_2013 (accessed on 15 April 2015).

- Santamaría, A.P.; Webber, M.; Santamaría, L.J. Effective school leadership for Māori achievement: Building capacity through Indigenous, national and international cross-cultural collaboration. In Cross-Cultural Collaboration and Leadership in Modern Organizations; Erbe, N.D., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2015; pp. 99–119. [Google Scholar]

- Milojevic, I. Educational Futures: Dominant and Contesting Visions; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

| Leader, Position, Identity | Characteristics of Applied Critical Leadership; Transformational Leadership (TL), Critical Pedagogy (CP), Critical Race Theory (CRT) and Perspective Lens—Axiology (PLA) |

|---|---|

| Sally (K-6 Principal), NZ European, female | —Going beyond the call of duty, doing whatever it takes to make it work for the student (PLA, TL) —Deliberate and purposeful acts of leadership that demonstrate social justice and equity (TL) —Ensured there is equal distribution of staff strengths across all year levels (CP) —Identified cultural groups that were overrepresented in raising student academic achievement (CRT) —Ongoing professional development; Sally did her PhD, reinforcing her role as a positive female role model (TL) —Local community engagement vital in sustaining relationships and forming alliances (CP) —Reflective and self-analytical in her actions, behaviours and practices (PLA) —Engaged in research about her community in Auckland where she grew up, by supporting local initiatives and reinforcing the cycle of giving back to your community (CP, CRT) |

| Bob (K-6 Deputy Principal), NZ European, male | —Served as a positive male role model for students, staff and wider school community (TL) —Mentored beginning teachers and teacher aids as a critical aspect of his leadership role (CP) —Shared new knowledge from professional development courses in staff meetings and provided training (TL) —Identified systemically underserved groups with regard to ethnicity, language and achievement and initiated meetings to address, collaborate and work towards inclusion (TL, PLA) —Acutely aware of racial prejudices and bias in Auckland, not prevalent from his place of origin—the South Island of NZ, where he experienced no racism. Therefore he overtly demonstrates and strives for social justice and equity in Auckland (CRT, PLA) —Practiced transparency in leadership (TL) —Deep belief in fairness and inclusiveness of all people (PLA) |

| Mary (K-6 Principal), NZ European, female | —Identified mentoring first-time principals as critical for her sustainability in educational and leadership roles (CP) —Beliefs and values about inclusiveness and openness were strongly shaped and influenced by her mother (PLA, CRT) —Engaged in research about her community to increase knowledge about Māori culture and other ethnic communities (CRT) —Created alliances with external stakeholders to address issues on environmental sustainability, social justice and equity (TL, CRT) —Sought transparency and collaborative practices (TL) —Re-examined the concept of justice and equity in light of reality which is contrary to her belief in regard to justice for the common good (CP, PLA) |

| Jill (K-6 Acting Principal), NZ European, female | —Identified issues at school with regard to race, ethnicity, languages, customs and student achievement and sought to bring about equitable outcomes for all (TL, CRT) —Beliefs and values about inclusiveness and charity were strongly shaped and influenced by her Catholic upbringing (PLA, CRT) —Although she originated from the North Island of NZ, she was raised in a provincial city that was predominantly NZ European and therefore sought to develop an awareness and understanding of various cultures, languages, especially Māori traditions, language and customs (TL, CP) —Demonstrated deliberate acts of social justice and equity to increase achievement of the underserved demographic of the school population (TL, CRT) —Community engagement was integrated in their school subculture and supported by biculturalism (CRT, TL) |

| Helen (K-6 Principal), Māori, Female | —Beliefs and values about identity were strongly shaped and influenced by her Māori heritage, upbringing and culture (CRT, PLA) —Acute awareness of systemically underserved groups, including Māori, and passionate to shift unequal cultural norms (CRT, CP) —Going beyond the call of duty, doing whatever it takes to make it work for the student, staff and community (PLA, TL) —Shared new knowledge from professional development as she believes that knowledge and power distributed is multiplied (TL, CP) —Consensus gained through critical conversations with the community, staff, parents and students (TL) |

© 2016 by the author; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jayavant, S. Mapping the Complexities of Effective Leadership for Social Justice Praxis in Urban Auckland Primary Schools. Educ. Sci. 2016, 6, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6010011

Jayavant S. Mapping the Complexities of Effective Leadership for Social Justice Praxis in Urban Auckland Primary Schools. Education Sciences. 2016; 6(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleJayavant, Sharona. 2016. "Mapping the Complexities of Effective Leadership for Social Justice Praxis in Urban Auckland Primary Schools" Education Sciences 6, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6010011

APA StyleJayavant, S. (2016). Mapping the Complexities of Effective Leadership for Social Justice Praxis in Urban Auckland Primary Schools. Education Sciences, 6(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci6010011