Leadership and Reshaping Schooling in a Networked World

Abstract

:- -

- how might schools move into the networked mode?

- -

- what is required to lead and manage a networked school community?

- -

- how will a networked school become defined less by its physical space and timetabled lessons, but by being networked and that learning can take place anywhere, anytime?

1. Introduction—Schooling in the 21st Century

...creative institutions are developing new models to serve students, such as providing open content over the network. ...Students can take advantage of learning material online, through games and programs they may have on systems at home, and through their extensive—and constantly available—social networks. The experiences... tend to happen serendipitously and in response to an immediate need for knowledge, rather than being related to topics currently being studied in school. ...having a profound effect on the way we experiment with, adopt, and use emerging technologies.[1]

- That there is a need to rethink and redefine schooling in a digital, networked world. This assumption provocatively suggests that the impact of technologies has disrupted other ways of working, such as media, retail, banking, and other forms of business, and that, similarly, education is not immune from the impact and potential of technological changes; and

- That leadership is needed to make transitions to a networked school community to be effected. This assumption draws upon the considerable educational leadership literature which highlights the critical role of leadership in schools which is needed to transform schooling.

2. Digital Technologies and Reshaping Schooling

3. Trends in New and Emerging Digital Technologies

- Time-to-Adoption Horizon: One Year or Less—Cloud Computing, Mobiles

- Time-to-Adoption Horizon: Two to Three Years—Game-Based Learning, Open Content

- Time-to-Adoption Horizon: Four to Five Years—Learning Analytics, Personal Learning Environments [1]

- Time-to-Adoption Horizon: One Year or Less—Cloud Computing, Mobiles Learning

- Time-to-Adoption Horizon: Two to Three Years—Learning Analytics, Open Content

- Time-to-Adoption Horizon: Four to Five Years—3D Printing, Virtual and Remote Laboratories

| Critical Challenge | Supporting Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1. Ongoing professional development needs to be valued and integrated into the culture of the schools. | “All too often, when schools mandate the use of a specific technology, teachers are left without the tools (and often skills) to effectively integrate the new capabilities into their teaching methods.” [18] (p. 9) |

| 2.Too often it is education’s own practices that limit broader uptake of new technologies. | “In many cases, experimentation with or piloting of innovative applications of technologies are often seen as outside the role of teacher or school leader, and thus discouraged. Changing these processes will require major shifts in attitudes as much as they will in policy.” [18] (p. 9) |

| 3. New models of education are bringing unprecedented competition to traditional models of schooling. | “Across the board, institutions are looking for ways to provide a high quality of service and more opportunities for learning. MOOCs are at the forefront of these discussions, and have opened the doorway to entirely new ways of thinking about online learning. K-12 institutions are latecomers to distance education in most cases…” [18] (p. 9) |

| 4. K-12 must address the increased blending of formal and informal learning. | “…designing an effective blended learning model is key, but the growing success of the many non-traditional alternatives to schools that are using more informal approaches indicates that this challenge is being confronted.” [18] |

| 5.The demand for personalized learning is not adequately supported by current technology or practices. | “The notion that one size-fits-all teaching methods are neither effective noracceptable for today’s diverse students is generally accepted among K-12 educators.” [18] (p. 10) |

| 6.We are not using digital media for formative assessment the way we could and should. | “Assessment is an important driver for educational practice and change, and… we have seen a welcome rise in the use of formative assessment in educational practice. However, there is still an assessment gap in how changes in curricula and new skill demands are implemented in education…” [18] (p. 10) |

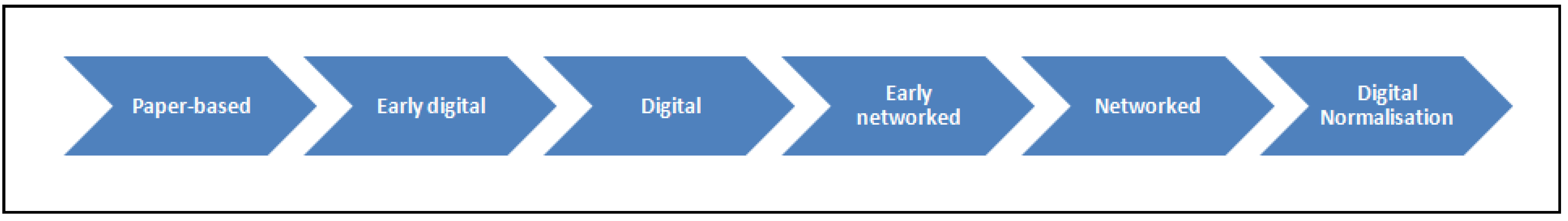

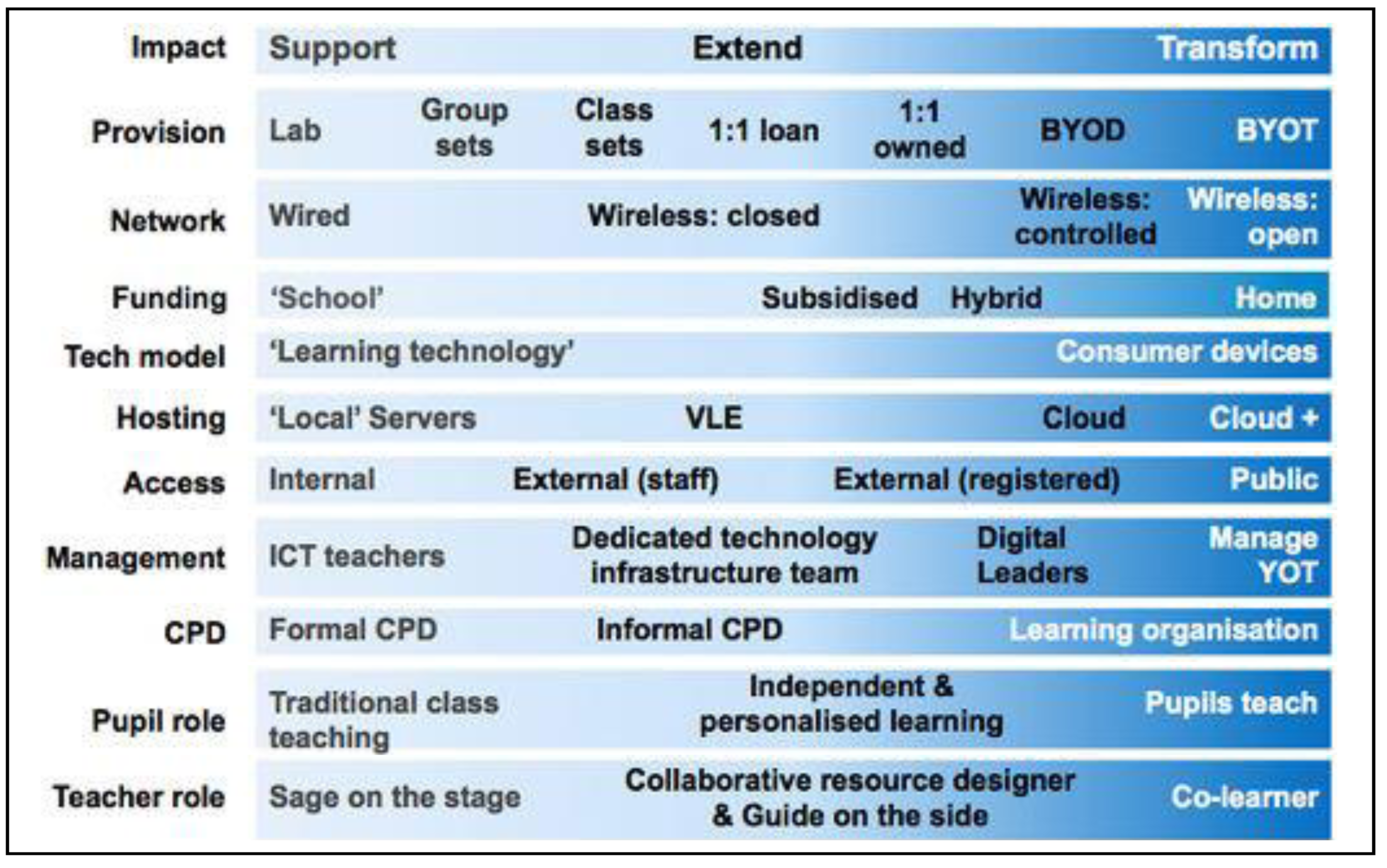

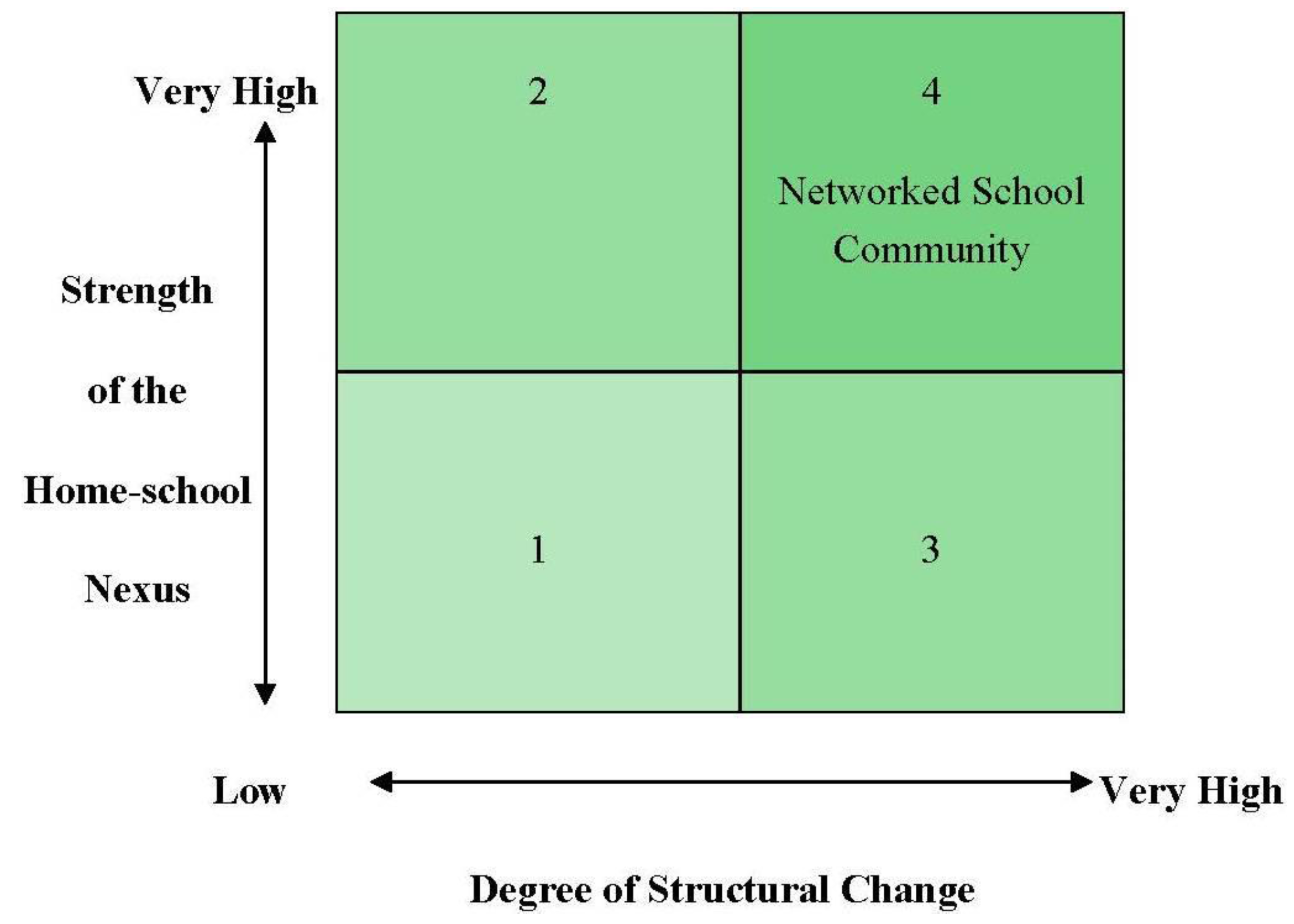

4. Conceptualising Evolutionary Stages of Schooling and Networked School Communities

recognise that their digital and networked facilities removes the school’s long-term reliance on students attending a physical place for learning and the necessity to continue operating as a largely insular organisation. They now begin to recognise the plethora of opportunities for human networking, and genuine collaboration with all the teachers of the young from birth onwards. It recognises the physical networks open the way for ever-greater and more effective human networking.[11]

Work rolls continuously around the world, following the sun, yet it is instantly accessible all the time by everyone whenever they need it. Boundaries are conceptual, not physical, in the virtual workplaces and need to be completely reconceived so that “physical site” thinking is no longer a limitation.[19]

a legally recognised school that takes advantage of the digital and networked technology, and of a more collaborative, networked and inclusive operational mode to involve its wider community in the provision of a quality education appropriate for the future.[3]

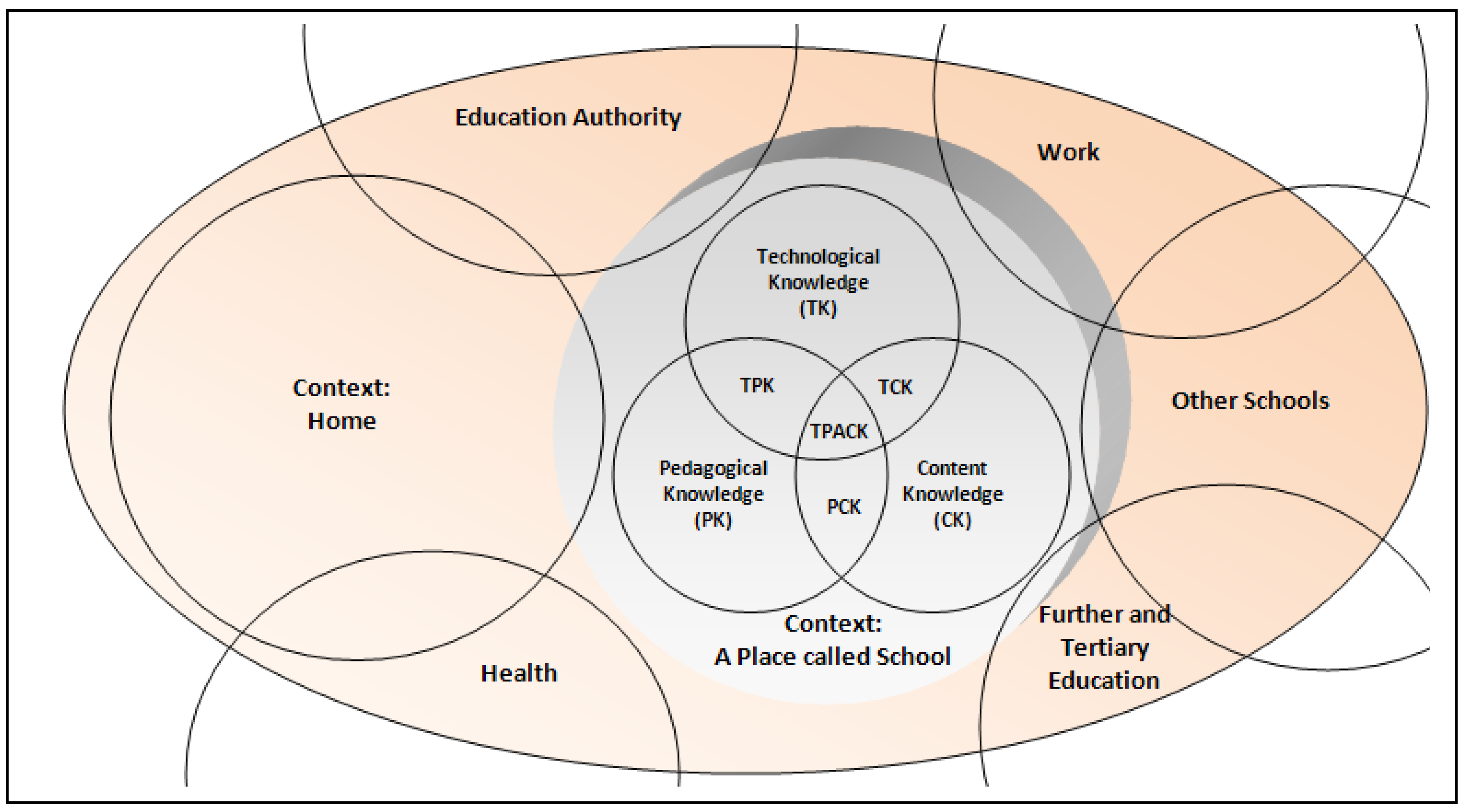

5. Rethinking the Balance—Networked School Communities and TPACK Capabilities

Kids lead high-tech lives outside school and decidedly low-tech lives inside school. This new “digital divide” is making the activities inside school appear to have less real-world relevance to kids. A blend of intellectual discipline with real-world context can make learning more relevant, and online technology can bridge the gap between the two.[20]

...there is the standing danger that the material of formal instruction will be merely the subject matter of schools, isolated from the subject matter of life experience... This danger is never greater than at the present time, on account of the rapid growth in the last few centuries of knowledge and the technical mode of skills.[21]

The TPACK framework suggests that the kinds of knowledge teachers need to develop can almost be seen as a new form of literacy… Viewing teachers’ use of technology as a new literacy emphasizes the role of the teacher as a producer (as designer), away from the traditional conceptualization of teachers as consumers (users) of technology.[24]

6. Guidance for Developing a Networked School Community

6.1. Expanding the Academic Focus

All we seem to hear about these days is failing teachers in failing schools. Those from business, government and the field of economics have all weighed in, criticising teachers, teacher educators and schools and offering often naive, misinformed or ideologically driven “remedies”.…What I do see is a blanket stigmatisation of teachers, principals, teacher educators and education system leaders. All these “solutions” ignore the fact that Australia still performs well on international measures of student achievement such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).[30]

Claims by the Australian government that Australian education will be “world-class” and “top 5” by 2025 could be interpreted to believe that Australian education is poor quality. Australian education is very high quality on “world-class” on all fronts. Statements of “top 5” relate to performance on 2 h-long standardised tests administered to a sample of students in a sample of schools in a number of countries that pay to participate in international comparison tests.[31]

The thirst for data became unquenchable. Policy makers in Washington and the state capitals apparently assumed that more testing would produce more learning. They were certain that they needed accountability and could not imagine any way to hold schools “accountable” without test scores. This unnatural focus on testing produced perverse but predictable results: it narrowed the curriculum; many districts scaled back time for the arts, history, civics, physical education, science, foreign language, and whatever was not tested.[33]

6.2. Expanding the Educational Perspectives

6.3. Addressing the Bureaucratic and Hierarchical Imbalances

6.4. Understanding the Complexity of Schooling and Overcoming Simplistic Solutions

It would be patently foolish to argue against the importance of teachers and principals. But to build a strategy for improvement on the premise that good principals produce good schools would be almost as foolish…Significant educational improvement of schooling, not mere tinkering, requires we focus on entire schools, not just teachers or principals or curricula or organization or school-community relations but all of these and more.[13]

6.5. Capitalising on the Largely Untapped Resources beyond a Place Called School

- Parents/Caregivers—Educated and motivated: Historically, developed nations now have the most educated cohort ever, with most not only motivated, but educationally ready to collaborate in the “teaching” of their young, and this expertise remains largely unrecognized, underused and undeveloped.

- Grandparents—Underdeveloped resource: Developed nations also now have grandparents who are similarly highly educated, and a human resource which can draw upon diverse and vast list experiences. Grandparents also constitute a largely unrecognised, undervalued and underdeveloped resource that is rapidly growing in size with the influx to their ranks of the “Baby Boomers” and increased life expectancy. In many situations, with both parents or the single parent working, grandparents have the potential to provide during and after school “teaching”. Grandparents’ current efforts and capacity need more recognition and to be supported by schools and teachers [39,40,42].

- Students—The ‘Net Generation: The ‘Net Generation [2,43] has long since normalized the everyday use of the digital and are using it to shape their lives and learning. Despite their acknowledged interest and competence in digital technologies, it needs to be asked if this is being listened to or drawn upon by their schools and teachers. The Project Tomorrow report in 2013 [17] provides compelling evidence that students, despite having increased access and ownership of their own personal devices, are not using these in schools.

- Students’ Homes—Technological advantage: In many instances, the digital capacity of the student’s homes has surpassed that of the classroom. The study by Lee and Ryall [44], which compared the digital technology in the homes of 30 Year 6 students with that of their classroom, found that the expenditure on digital technologies in the home was conservatively a multiple of 15 times that of the classroom. This home-school digital technology divide is growing through the acquisition of mobile computing, such as iPads, iPhones, and use of social media. Networked school communities enable the home-school divide to be better viewed as a home-school difference that can be capitalised upon.

- Potential Resource or Threat: There are media reports and school system policies being developed and implemented which is this potential resource as a threat, with personal digital technologies being misused by some students. The knee-jerk reaction has tended to be quick to ban their access and use in schools.

...to happen serendipitously and in response to an immediate need for knowledge, rather than being related to topics currently being studied in school. ...having a profound effect on the way we experiment with, adopt, and use emerging technologies.[1]

Parents have always been allies and advocates for their children in the traditional school environment. With new digital choices, today’s parents are now enabling greater educational opportunities for their children, both in and out of school, and at the same time, empowering a new paradigm for the role of parents in education.[45]

7. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Johnson, L.; Adams, S.; Haywood, K. The NMC Horizon Report: 2011 K-12 Edition. Austin, Texas: The New Media Consortium, 2011; pp. 5–6. Available online: http://www.nmc.org/pdf/2011-Horizon-Report-K12.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Tapscott, D. Grown Up Digital. How the Net Generation Is Changing Our World; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Finger, G. Developing a Networked School Community: A Guide to Realising the Vision; ACER Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mukerji, A. Consumerization of Technology: A Set of New Imperatives for the Media and Communications Industry. Communications and Media. p. 31. Available online: http://www.wipro.com/Documents/Wipro_Winsights_Article_7_Consumerization_of_Technology.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Dahlstrom, E. Executive Summary: BYOD and Consumerization of IT in Higher Education Research. Educause Review Online. 2013. Available online: http://www.educause.edu/ero/article/executive-summary-byod-and-consumerization-it-higher-education-research-2013 (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- May, M.E. The Rules of Successful Skunk Works Projects. 2012. Available online: http://www.fastcompany.com/3001702/rules-successful-skunk-works-projects (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Lee, M.; Gaffney, M. Leading a Digital School: Principles and Practice; ACER Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Finger, G. The Impact of School Organisational Structure on Teacher Agency and Educational Contribution. ACE Notepad. Number 9 2010. 2010. Available online: http://austcolled.com.au/notepad/article/improving-impact-school-organisational-structures-teachers-agency-and-educational-co (accessed on 25 January 2014).

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M.J. Introducing Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New York City, 24–28 March 2008; 2008. Available online: http://punya.educ.msu.edu/presentations/AERA2008/MishraKoehler_AERA2008.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Rittel, H.; Webber, M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Broadie, R. The Evolutionary Stages of Schooling Key Indicators A Discussion Paper. 17 July 2013. Available online: http://schoolevolutionarystages.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Evolutionary-Stages-of-Schooling4.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Twining, P. Digital Technology Trends. 2013. Available online: http://edfutures.net/Digital_technology_trends (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Goodlad, J. A Place Called School; McGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Collins. In Australian Dictionary; Harper Collins: Glasgow, UK, 2007.

- Wikipedia. School. 2013. Available online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/School (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Chase, A. Digital Technology In- and Out-of-School: A Comparative Study of the Nature and Levels of Student Use and Engagement. Executive Summary. Unpublished Doctor of Education, Graduate School of Education, The University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Project Tomorrow. From Chalkboards to Tablets: The Emergence of the K-12 Digital Learner Speak Up 2012 National Findings K-12 Students. June 2013. Available online: http://www.tomorrow.org/speakup/pdfs/SU12-Students.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Johnson, L.; Adams Becker, S.; Cummins, M.; Estrada, V.; Freeman, A.; Ludgate, H. NMC Horizon Report: 2013 K-12 Edition; The New Media Consortium: Austin, TX, 2013. Available online: http://http://www.nmc.org/pdf/2013-horizon-report-k12.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Lipnack, J.; Stamps, J. The Age of the Network: Organizing Principles for the 21st Century; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Institute of Technology/Institute of Design. Schools in the Digital Age. 2007. Available online: http://trex.id.iit.edu/intranet/seeid/sp_projects/files/28/documents/macarthurfinalreport1.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Dewey, J. Democracy and Education; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L. Knowledge and teaching: foundations of the new reform. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1987, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, M.J.; Mishra, P. What happens when teachers design educational technology? The development of technological pedagogical content knowledge. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2005, 32, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Koehler, M. Technological pedagogical Content Knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2006, 108, 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, G.; Jamieson-Proctor, R. Teacher Readiness: TPACK Capabilities and Redesigning Working Conditions. In Developing a Networked School Community: A Guide to Realising the Vision; Lee, M., Finger, G., Eds.; ACER Press: Camberwell, VIC, Australia, 2010; pp. 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, M.; Mishra, P. Introducing TPCK. In Handbook of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK) for Educators; AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology; Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). Curriculum. 2013. Available online: http://www.acara.edu.au/curriculum/curriculum.html (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). NAPLAN. Available online: http://www.nap.edu.au/naplan/naplan.html (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- OECD. Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). 2013. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/pisa/ (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Dinham, S. A Political Education: Hijacking the Quality Teaching Movement. 2012. Available online: http://theconversation.com/a-political-education-hijacking-the-quality-teaching-movement-9017 (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Cumming, J. Gonski Review—ACE Members Have Their Say—Professor Joy Cumming. ACE Notepad 912. September 2012. Available online: http://austcolled.com.au/notepad/issue/0912?display=full (accessed on 25 January 2014).

- Thomson, S.; Di Bartoli, L. Preparing Australian Students for the Digital World: Results from the PISA 2009Digital Reading Literacy Assessment; ACER Press: Camberwell, Australia, 2012. Available online: http://www.acer.edu.au/documents/PISA2009_PreparingAustralianStudentsForTheDigitalWorld.pdf. (accessed on 25 January 2014).

- Ravitch, D. Reign of Error: The Hoax of the Privatization Movement and the Danger to America’s Public Schools; Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Petre, D.; Harrington, D. The Clever Country? Australia’s Digital Future; Pan Macmillan: Sydney, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, T. The World Is Flat, 2nd ed.; Farrar, Straus Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. Early Years Learning Framework for Australia: Belonging, Being and Becoming; Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace: Canberra, Australia, 2009. Available online: http://www.deewr.gov.au/Earlychildhood/Policy_Agenda/Quality/Documents/Final%20EYLF%20Framework%20Report%20-%20WEB.pdf (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Hart, B.; Risely, T. The Social World of Children Learning to Talk; Paul Brooks: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wagaman, J. Teaching Self Control has Long Term Benefits. Suite 101.com. 2011. Available online: http://www.suite101.com/content/teaching-children-self-control-has-long-term-benefits-a338053. (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Strom, R. Building a Theory of Grandparent Development. 1997. Available online: http://www.public.asu.edu/~rdstrom/GPtheory.html (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Strom, R.; Strom, P. Parenting Young Children Exploring the Internet, Television, Play and Reading; IAP Charlotte: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdry, H.; Crawford, C.; Goodman, A. Drivers and Barriers to Educational Success. 2009. Institute of Fiscal Studies DCSF–RR102. Available online: http://eprints.ucl.ac.uk/18314/1/18314.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2013).

- Lee, M.; Hough, M. Involving the Nation’s grandparents in the Schooling of its Young. 2011. Available online: http://malleehome.com/?p=143 (accessed on 18 September 2013).

- Tapscott, D. Growing Up Digital: The Rise of the Net Generation; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Ryall, B. Financing the Networked School Community: Building upon the Home Investment. In Developing a Networked School Community: A Guide to Realising the vision; Lee, M., Finger, G., Eds.; ACER Press: Melbourne, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Project Tomorrow. The New 3 E’s of Education: Enabled, Engaged and Empowered—How Today’s Students are Leveraging Emerging Technologies for Learning. 2011. Available online: http://www.tomorrow.org/speakup/pdfs/SU10_3EofEducation_Students.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2013).

- Shirky, C. Here Comes Everybody: Organizing Without Organizations; Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Finger, G.; Lee, M. Leadership and Reshaping Schooling in a Networked World. Educ. Sci. 2014, 4, 64-86. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci4010064

Finger G, Lee M. Leadership and Reshaping Schooling in a Networked World. Education Sciences. 2014; 4(1):64-86. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci4010064

Chicago/Turabian StyleFinger, Glenn, and Mal Lee. 2014. "Leadership and Reshaping Schooling in a Networked World" Education Sciences 4, no. 1: 64-86. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci4010064

APA StyleFinger, G., & Lee, M. (2014). Leadership and Reshaping Schooling in a Networked World. Education Sciences, 4(1), 64-86. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci4010064