1. Introduction

Departmental change groups have evolved from the need to address systemic barriers disproportionately affecting marginalized students in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) spaces (

Reinholz et al., 2019). By engaging at the department level, these groups can assess and modify policies that impact students directly (

Reinholz et al., 2019;

Bolick et al., 2025b). Yet, these departmental change groups rarely engage students in their efforts, much less as equitable partners.

This study stems from a larger foundational research project, Achieving Critical Transformations in Undergraduate Programs in Mathematics (ACT UP Math; NSF ECR# 2201486), which follows three university Networked Improvement Communities (NICs) (

Bryk, 2020;

Bryk et al., 2015;

Martin et al., 2020) working towards critical transformations in introductory mathematics courses. The project intended to broaden participation in introductory college mathematics courses, which are frequently viewed as gatekeepers to STEM degrees (

Redmond-Sanogo et al., 2016) and also reach the widest range of students; in fact, over 90% of students enrolled in college mathematics are taking calculus or a preceding course (

Laursen et al., 2019). We define a NIC as a group of stakeholders with a shared aim and deep knowledge of the problem, who use improvement cycles to make data-informed decisions (

Penuel et al., 2020). Our analysis follows a NIC with student and faculty members focused on improving access to introductory mathematics courses and students’ positive relationships with mathematics. The NIC engaged in two improvement cycles over two years that included observation (e.g., collecting data), reflection (e.g., reflecting on the data to determine interventions), planning (e.g., developing an action plan or goal), and action (e.g., implementing the plan). Throughout that process, the NIC fostered equitable, reciprocal relationships between student and faculty NIC members (

Bolick et al., 2025b).

This work contributes to a growing but still limited body of research that positions students as partners in institutional change efforts. Students are commonly included in partnerships centered around improving teaching and learning through curriculum development and Scholarship of Teaching and Learning studies (

Healey et al., 2014;

Marquis et al., 2016;

Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017). Yet, because student–faculty partnerships within NICs remain underexamined, little is known about how students experience a sense of belonging in these spaces. In this study, we analyzed data from student members’ first semester and last semester in the NIC to assess their sense of belonging (

Hagerty et al., 1992) across time by answering the following research question:

How does sense of belonging manifest and develop across time for student members in a NIC focused on improving introductory mathematics?

2. Belonging and Students as Partners

Johnson (

2022) defines sense of belonging in postsecondary education as a “social-ecological phenomenon that is shaped by both proximal factors, such as interactions, and distal ones, such as cultural norms and institutional policy” (p. 3). Structural belonging captures the institutional conditions and cultural norms that support belonging within a community and requires the critical transformation of inequitable structures (

Johnson, 2022). This emphasis on structure parallels

Allen et al.’s (

2021) conditions supporting students’ overall sense of belonging. It also aligns with

Hagerty et al.’s (

1992) definition of belonging, highlighting the importance of involvement in a system and the recognition of individual contributions as integral. Authentic student–faculty partnerships, where students are not only engaged with the group but are vital to its direction and success, are thus essential for developing students’ sense of belonging.

We situate this work within the “students as partners” framework (

Cook-Sather et al., 2014,

2018), which repositions students as faculty peers and challenges the agentic power imbalances present in higher education (

Cook-Sather & Agu, 2013;

Cook-Sather et al., 2018). The intent of a student–faculty partnership is to rethink the value students bring to their own education, pushing back against traditional power structures and including student perspective in postsecondary education (

Cook-Sather & Agu, 2013;

Cook-Sather et al., 2018). Partnerships are sustained through three pillars: reciprocity, responsibility, and respect (

Cook-Sather et al., 2014), together fostering belonging. Including students as partners in education is challenging due to institutional norms and structures that promote competition and individualism which may dilute authentic partnerships (

Peters & Mathias, 2018), skepticism towards student–faculty collaborations, and finding balance between selectivity and inclusivity (

Bovill et al., 2016). These barriers directly influence what change efforts are considered feasible and who is allowed to participate in policy-making at the departmental and institutional levels, often limiting student participation in critical change efforts. However, student–faculty partnerships can disrupt hierarchies, creating counterspaces where the lived experiences of students are valued as motivation and evidence in the change-making process (

Cook-Sather & Agu, 2013).

4. Methods

4.1. Institution and Participants

This study took place at Alpha University (AU) in the western United States. In addition to being a productive research institution, AU is a federally designated Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander-serving institution and Hispanic-serving institution

1. The institution is described by students and faculty as diverse, inclusive, and supportive, three characteristics that push students to engage positively with peers and faculty members and act as catalysts for student growth. NIC leaders recruited students with varying levels of mathematical experience—from students who only took a single required mathematics course to mathematics graduate students. The NIC ran for two one-year cycles in 2023 and 2024. Throughout that time, there were four undergraduate student members, two graduate student members, one lecturer faculty member, and four tenure-track faculty members (

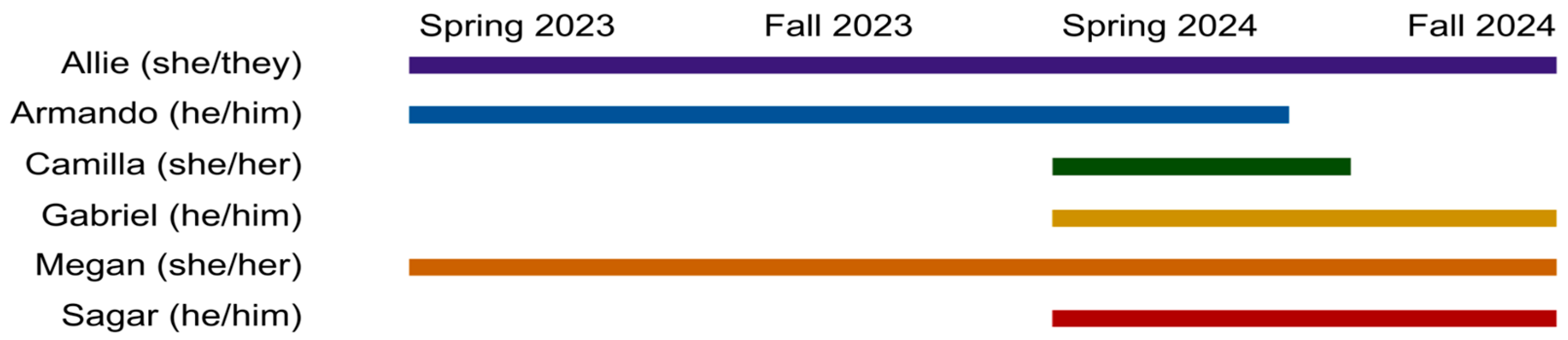

Figure 1). NIC membership changes were due to availability, graduation, a transition from student to faculty, and faculty sabbatical. Additionally, one participant, Camilla, was excluded from this analysis due to her single-semester involvement in the NIC. Participants have selected pseudonyms (whether their own name or a code name) and pronouns to represent themselves throughout the manuscript.

Allie identifies as white and gender queer. They were an undergraduate mathematics student who transferred to AU from a local community college, where they had changed their major several times and completed their math coursework up to differential equations. They served as an undergraduate learning assistant for lower-division math courses throughout their time as an undergraduate and were on a pre-teaching track, enrolling in a high school teaching credential program after graduation.

Armando identifies as Mexican-American, cisgender male. He joined the NIC as a computer science major undergraduate student who transferred to AU after taking courses at two local community colleges (including calculus, linear algebra, and discrete mathematics). He did not take any math courses at AU but did take one statistics course after transferring. He had completed three semesters before joining the NIC for his remaining two semesters at AU and continued to work with the NIC after graduating in Fall 2023.

Gabriel identifies as a Filipino-American, cisgender male. He attended an unaccredited, private Christian school through 12th grade, then their adjoining Bible college. Having been fascinated with mathematics since childhood, he then attended a community college and obtained an associate’s degree in math and physics. Community college helped him develop logical, political, ethical, and scientific points of view. After community college, he started his upper division mathematics education at AU as a math undergraduate interested in mathematics education and becoming a math teacher. Since joining the NIC as an undergraduate, he has received his bachelor’s degree and started taking graduate-level math courses.

Megan identifies as a white, cisgender female. Being a subject she excelled in throughout her K-12 years, math was the obvious choice for her major when she enrolled in a four-year university right out of high school. However, higher-level math did not come easily, and Megan struggled and failed many math courses, resulting in her having to leave the university and experiencing an identity crisis—maybe math wasn’t her thing? Having completed most of the GE requirements, she was able to focus on math when attending AU roughly eight years later (per her mother’s request) and fell back in love with the subject. Since receiving her bachelor’s and master’s degrees at AU, she has remained at the university as a lecturer.

Sagar identifies as an Asian Indian, cisgender male. He decided to pursue graduate study in mathematics with the goal of teaching. This goal was inspired by years of working as a math tutor at a local community college. Having an undergraduate degree in biology did not provide a sufficient background for studying mathematics, so he completed one year of undergraduate mathematics coursework in algebra and analysis at AU prior to entering the graduate program. As a graduate student, he developed an interest in applied mathematics research and continued developing teaching skills as a teaching associate while contributing to the NIC.

4.2. Data Analysis and Analytical Framework

We take a retrospective, qualitative, longitudinal approach (

Saldaña, 2003) to examine student members’ sense of belonging in the NIC across time. Throughout the analysis, we consider the critical elements of qualitative longitudinal research: time, process, and change (

Holland et al., 2006). Alpha University’s NIC iteratively developed and implemented two concurrent goals: (1) dismantling the placement system for introductory mathematics courses and (2) creating programming that connects students to the utility value of mathematics (

Bolick et al., 2025b). Not all students joined the NIC at the same time; some students participated in the NIC for one year, while others participated for two years (

Figure 1).

NIC meetings and subsequent actions provided the process through which student NIC members were able to experience different components of belonging (

Allen et al., 2021). The NIC had biweekly meetings during each spring semester and monthly whole-group meetings with smaller breakout meetings during each fall semester. Data from students’ experiences during their first and final semesters as part of the NIC were examined. During the first year, two tenure-track co-leads facilitated discussions with structures that would support equity of voice and planned activities that would result in whole-NIC decisions. During the second year, the NIC moved to a rotating facilitation structure to further disrupt power dynamics. In this rotating facilitation structure, two NIC members facilitated each meeting, and each member facilitated two meetings in a row in a staggered format.

Changes in NIC students’ sense of belonging across time were examined using journal and interview data collected from students during their first semester and final semester with the NIC. Journal and interview prompts varied slightly depending on the length of time each individual had been in the NIC, and what was most salient to individuals in their journals. Prompts asked about individuals’ motivations, perceptions, and experiences in the NIC and about the roles and responsibilities and decision-making practices of the NIC. A complete index of journal and interview prompts for each semester is included in the

Supplementary Materials. In the

Section 5 we reference the semester each data source is from, and the data from journals as (J-#) and interviews as (I-#) to delineate between different iterations of each data source. Based on the journals and interviews, the research team constructed rich descriptions of each NIC member’s development over the life of the NIC (including both faculty and students), focusing on individuals’ backgrounds, roles within the NIC, and personal growth. These rich descriptions were based on participants’ interview and journal data over time. We then refined the definitions in

Allen et al.’s (

2021) sense of belonging framework to ensure that, taken together, the four constructs of belonging would capture the major themes in NIC members’ stories.

We continued to structure our analysis through the lens of each construct of belonging, narrowing our focus to study student NIC members’ experiences in particular. Using a codebook based on the four constructs of belonging, as described in

Table 1, we deductively coded each student participant’s first- and last-semester journals and interviews. Each data source was initially coded by at least one member of the research team, and subsequently reviewed by at least one other researcher. All codes were discussed to establish consensus among the research team. Looking across participants, we developed themes within each code for both first- and last-semester data and noted how themes persisted, transformed, or emerged over time.

The following

Section 5 breaks down how each construct appears in the student NIC members’ first and last semester, while including the student NIC members’ joint narrative reflection about their experiences not captured in the analysis. The student NIC members are featured as authors on this manuscript because of their extensive member checking and written reflection, which helped shape our results and provide greater depth to our analysis by capturing experiences between the two time points of interest that were not seen through the data sources.

5. Results

In this section, we share a longitudinal analysis of each construct of belonging based on students’ reflections on their experiences across their time spent as members of the NIC. Our longitudinal findings demonstrate explicit connections to each construct of sense of belonging and highlight the shift each construct has from students’ first to final semesters in the NIC. Overall, we found that NIC members’ sense of belonging developed over time, supporting both individual agency in students and the identity of the NIC as a community working toward a common goal.

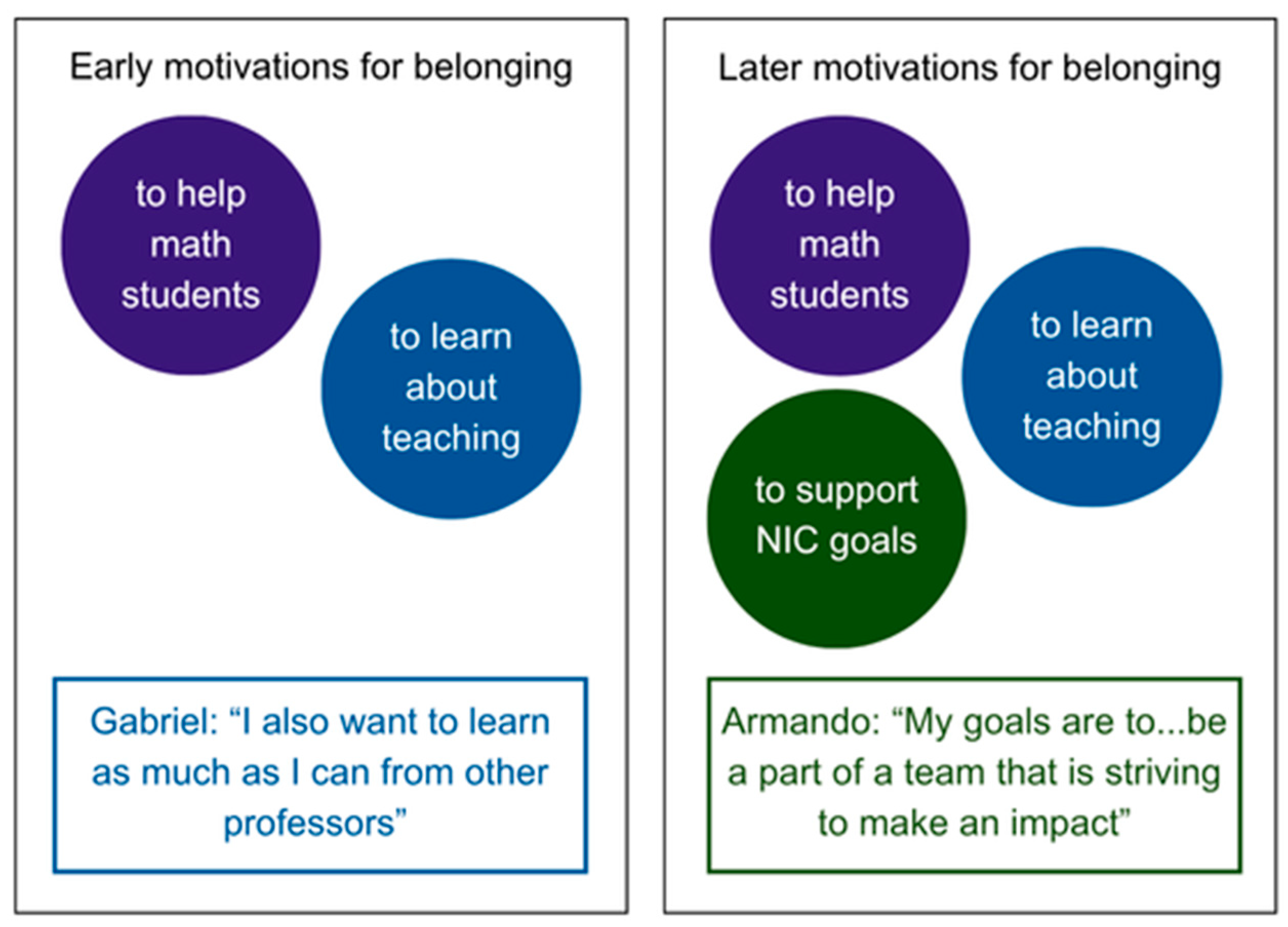

5.1. Shift from Individual to Collective Motivations

For many student participants, the motivation to join the NIC stemmed from a desire to contribute positively to students’ mathematics experiences. This motivation was informed by their experiences as math students and by serving in instructional roles, such as being a graduate teaching associate (TA) or undergraduate learning assistant (LA). Megan, for example, elaborated on her reasoning for joining the NIC: “I really love just the whole idea of what everyone was doing [in the NIC] … help[ing] students … mak[ing] math more equitable” (Sp_23, I-1). Meanwhile, Armando was motivated by negative secondary school math experiences that influenced his desire to “make a positive impact in the math department” (Sp_23, I-1) and “give people [the] opportunity to… not hate [math] in a way” (Sp_23, I-1). Sagar’s motivation to join the NIC stemmed from his prior experiences working with a diverse population of community college students. He wanted to learn more about “how changes are made in mathematics education,” “how the current state of [mathematics education is] being assessed,” and “how students are moving forward with their education, especially with respect to math” (Sp_24, I-1). Allie and Gabriel both identified deeply with the mission of the NIC based on their interests in teaching mathematics. Allie shared, “I wanted to be part of [the NIC] because I want to become a math teacher and have always been interested in how I could improve teaching methods” (Sp_23, I-1). Similarly, Gabriel communicated, “I do intend to become a math teacher at the end of my education career, and I also want to learn as much as I can from other professors” (Sp_24, I-1).

Reflecting on their motivations after participating for several semesters, Armando and Megan both recounted their initial interest in helping students as a significant motivator for their sustained engagement in the NIC. Armando elaborated: “I believe that the opportunity to make an impact at [AU] is what inspires my continual engagement” (Fa_23, J-2). Similarly, Megan’s reason for continuing revolved around her experiences supporting students prior to the NIC and through the implementation of the first goal:

Being an instructor and a math tutor for most of my life, I have always strived to understand how to help students better. I feel like that really motivated me to be involved and to want to help in every way possible, every aspect of the group. Knowing that I was potentially helping someone get through school faster and with more motivation, because they had more control, makes me so happy.

(Fa_24, J-2)

While student NIC members remained connected to their original reasons for participation, over the course of the two-year cycle, their motivations expanded to include the collective aims of the NIC (

Figure 2). The NIC’s shared goals had a significant impact on Allie, who found the NIC “a bit overwhelming for sure in the beginning, but realizing that it was a collective goal and everybody was there to support everybody made it not as much of a low light. [Being a part of the NIC] wasn’t as scary” (Fa_24, I-1). Meanwhile, having a shared goal among student and faculty NIC members shaped Armando’s evolving perspective; he attributed his sustained engagement to “being surrounded by professors who feel that same desire to help their students” (Fa_23, J-2) and shifted his motivations to be community-based. For example, Armando explained, “My goals are to help the NIC achieve their goals, help the math department and math students at [AU] thrive in their respective goals, and be a part of a team that is striving to make an impact at the university” (Fa_23, J-1). These reflections demonstrate that as the NIC developed, students increasingly saw themselves as valued members of the group and key contributors to systemic change. Their individual goals expanded and developed into a shared investment in the NIC’s mission, creating a powerful synergy between individual identities and collective action.

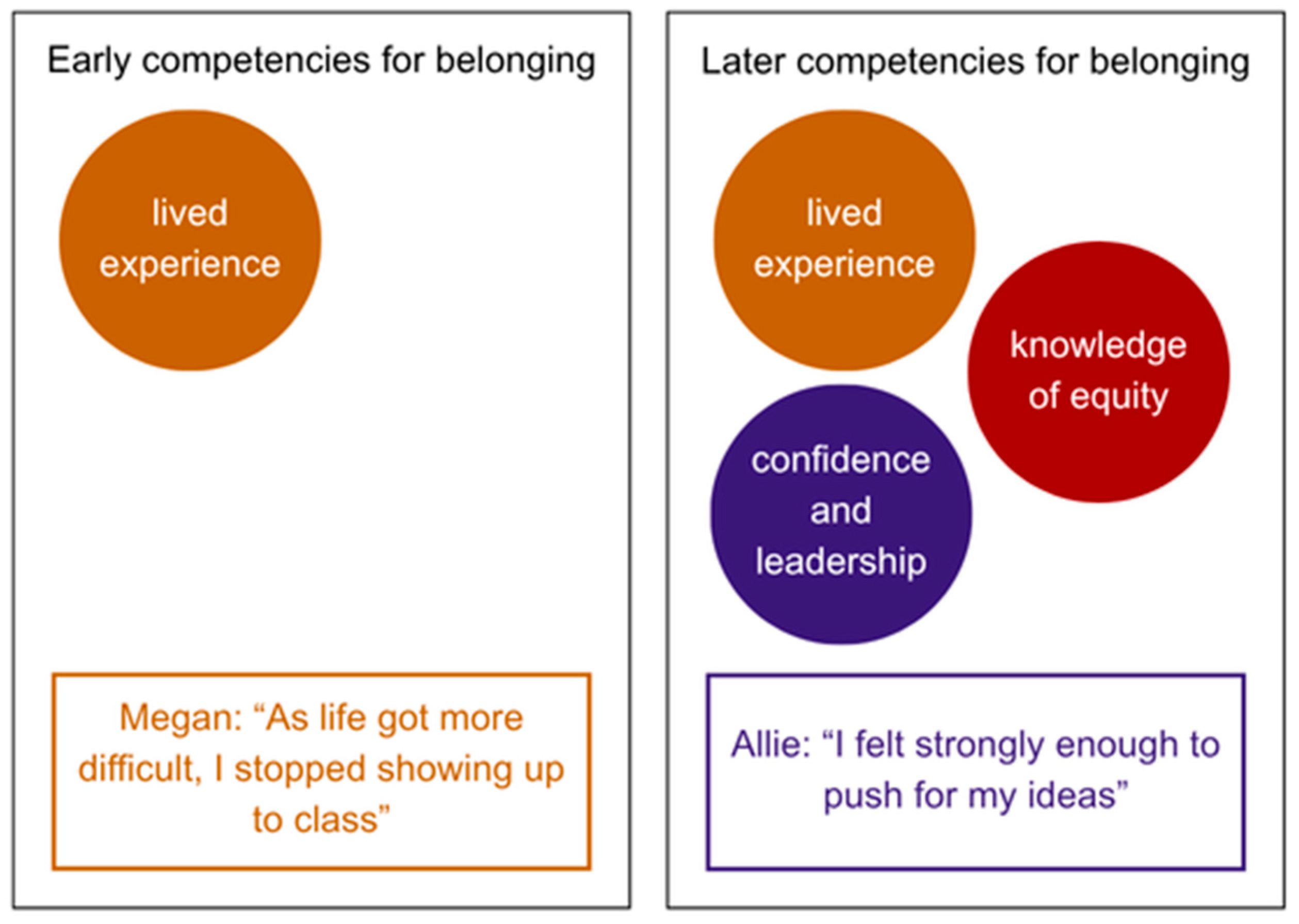

5.2. Developing Professional and Leadership Competencies

Students entered the NIC with varying competencies for belonging and drew upon their first-hand knowledge of the student experience to make connections and influence the NIC’s goals and direction. Thus, students’ competencies in areas such as mathematics or being a transfer student influenced their sense of belonging in the NIC.

Students’ varied experiences with mathematics surfaced common themes of confidence and insecurity. Both Megan and Allie found that they are strong mathematics students but also recounted moments when their confidence in mathematics was shaken; often due to external factors or increasing difficulty in material. For example, Megan reflected on her senior year of high school: “as life got more difficult, I stopped showing up to class physically and mentally” (Sp_23, J-1). Allie, who had previously relied on natural ability, recognized a turning point when material became more challenging and they “didn’t know how to study” (Sp_23, J-1). These narratives demonstrate that student NIC members were skilled and competent in what it means to experience mathematics as a student, including navigating their journeys, learning concepts and different ways of studying, and dealing with learning and personal challenges. Thus, student NIC members were positioned to relate to current student experiences and provide insight into the challenges students face in mathematics courses, an impetus for the NIC’s second goal.

Students’ lived experiences were also leveraged to develop the NIC’s first goal, which was about mathematics placement for first-year STEM students. For example, Gabriel and Allie shared their experiences with introductory mathematics placement systems outside of AU and how their initial placements impacted their mathematics journeys. Gabriel had benefited from a self-placement system at another postsecondary institution. He explains, “if self-placement wasn’t a thing for my lower division classes, I would be set back another 2 years, and I would not be here talking to you” (Sp_24, I-1). However, Allie was not as fortunate: her placement into mathematics was “horrible” (Sp_23, I-1). She described being placed into introductory college algebra and having to take the entire sequence of courses to reach differential equations, an experience that led them to advocate for improved placement systems at AU. Competencies that students had already developed based on their experiences as students and educators shaped the NIC’s goals, validating those experiences and fostering a sense of community among students in the NIC.

As student members worked on the NIC’s goals, they developed new competencies that reflected both personal and professional growth. They became more confident contributing to the NIC and taking on leadership roles. Armando, who described himself as a “quiet person” during his first semester in the NIC (Sp_24, I-1), explained how the NIC helped him gain new perspectives about subjects like working with students and college admissions, which, combined with new experiences like conferences, supported him in feeling more comfortable speaking up during meetings (Sp_24, I-1). Allie shared similar experiences in gaining confidence in the NIC, and was able to carry that confidence to other situations, sharing:

As a student teacher, you would think that would just– I’m just here to observe. But now, being comfortable with the NIC and sharing my ideas … I will often be the first person talking or sharing ideas…I think I took a couple of the teachers by surprise with how much I was willing to contribute, and I felt strongly enough to push for my ideas. I think that’s the biggest thing is my confidence that I’ve developed through the NIC.

(Fa_24, I-1)

Student NIC members also deepened their engagement with diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), especially as related to teaching mathematics. Gabriel and Megan, in particular, developed critical consciousness during their time in the NIC as a counter to their “sheltered” (Gabriel, Sp_24, I-1) upbringings. Gabriel grew up in an environment where diversity in gender and sexuality was presented as “counteractive to a good life” (Sp_24, I-1). Being involved in the NIC and having the opportunity to talk to people about their personal experiences helped him challenge these “closed” (Sp_24, I-1) perspectives. Similarly, Megan had never much thought about diversity because “it wasn’t something [she] saw nor was it something talked about” (Sp_23, J-3). By the middle of Megan’s first semester in the NIC, she realized that the NIC had “greatly influenced [her] thoughts on what it takes to support marginalized students” (Sp_23, J-4), motivating her to be more compassionate. Later, Megan confidently offered a systemic critique, observing that the education system “is seemingly designed so that only certain groups [of students] can be successful or at least in a way that makes it hard for certain groups to be successful” (Sp_23, J-4).

The professional competencies and skills students learned during their time in the NIC extended beyond DEI into the realms of research and data analysis, allowing them to cultivate belonging by making substantial contributions to NIC activities. For example, Allie initially thought that data analysis sounded intimidating but grew to realize “this isn’t as scary as I thought it was going to be, and spreadsheets are our friends” (Fa_24, I-1). Gabriel described the experience of leveraging these competencies during group problem-solving:

Whenever we had to pair off, … it was more so about how we can use our experiences collectively to solve the problem, rather than “oh, I’m, I have this title” or “I’m this person.” It had more to do with, “oh, we have this problem. What do we know about this problem that we can use to solve the problem?” And so it really felt like you were in a room full of equals.

(Sp_24, I-1)

Over time, the skills students developed as they were analyzing NIC data also reinforced students’ sense of validation and value within the NIC. Megan, for instance, explained: “I understand that data comes really from everywhere, like even just from our own personal experience” (Fa_24, I-1). Students found that this validation of their personal and collective experiences became a throughline in their NIC participation, fostering both belonging and the development of leadership skills (

Figure 3).

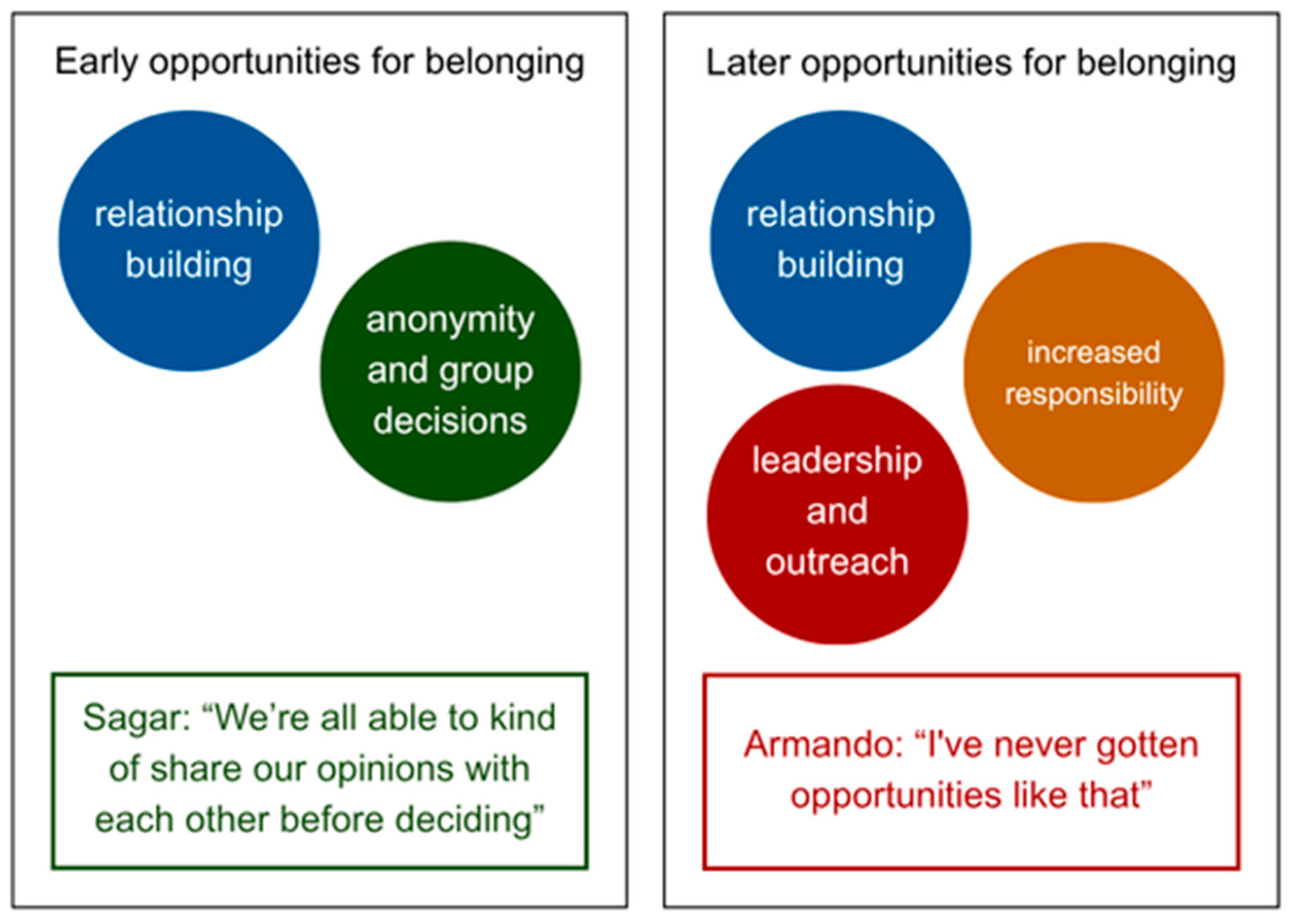

5.3. Taking on New Responsibilities Through Opportunities for Belonging

Student NIC members discussed a variety of opportunities they had to build relationships with other NIC members that made them feel like peers. These opportunities were reinforced by student NIC members receiving the same stipend as faculty NIC members, and by the structure of NIC meetings. For instance, the NIC spent several meetings getting to know each other and co-developing community norms, which they reviewed at each meeting. Megan described these activities as important in developing a “nice, friendly, and welcoming” community of mutual respect within the group, which, over time, helped her feel “more comfortable … and confident speaking up” (Sp_23, J-2). During NIC meetings, NIC members often broke up into smaller teams, or pairs of students and faculty. Megan found these smaller groups valuable, as the pairs were “able to build off each other and have really good conversations” (Sp_23, J-3). This collegiality existed beyond the regular NIC meetings and topics. Sagar discussed how they always had an opportunity to “reach out to each other” (Fa_24, I-1). Similarly, Gabriel shared that NIC members would “often end up talking beyond the meeting recordings” about “personal things,” and so relationships between NIC members felt both professional and personal (Sp_24, I-1). By the end of the NIC’s cycle, the opportunities to build relationships between students and faculty shifted Megan’s perspective from faculty members being placed “on a pedestal” to a perspective that “humanized them in a way” (Fa_24, I-1).

The NIC’s goals, ideated by the entire NIC and decided on through an anonymous voting process, gave student members a sense of belonging through the ability to be an active decision-maker as soon as they joined the NIC. Megan described the decision-making process as “very equal” (Sp_23, I-1), noting that “everyone gets to give their input, and everyone has time to think about everything” (Sp_23, I-1). Although the primary goals of the NIC did not change as new student members joined, new NIC members still expressed feeling like a part of the collective decision-making process of the NIC. Sagar described the decision-making process as follows:

So questions are given, like posed, to the entire NIC as a group. After taking time to internally think about what actions we should take, we’re all able to kind of share our opinions with each other before deciding on what direction to move.

(Sp_24, I-1)

In his descriptions of how the NIC operated, Sagar emphasized that these decisions were made as a team. Like other students in the NIC, Sagar felt uncomfortable, at first, in contributing his ideas, but emphasized that the open discourse during NIC meetings and “constant open environment for input” made it “easier to participate” and share his ideas (Sp_24, I-1).

Once student NIC members began to feel more comfortable collaborating in the NIC, they were able to take up opportunities to develop specialized roles within the NIC. For example, Megan was heavily involved in both goals but directly identified leading the “math mingle and munch event” (Fa_24, I-1) as the turning point for her confidence. After the student and faculty NIC members “worked together to plan [the math, mingle, and munch event],” Megan shared, “I was really a lot more comfortable speaking up in the meetings and being part of the events” (Fa_24, I-1). Megan developed the specialized roles of organizing mathematics review events as well as leading the student placement recruitment, coordination, and student interviews. Allie was similarly responsible for orchestrating the review sessions and primarily focused on planning material and preparing fellow learning assistants. Armando, Sagar, and Gabriel specialized in data analysis for various portions of the goals, including the self-placement goal. The NIC supported Armando, Allie, Sagar, and Gabriel’s attendance at the Society for Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics & Native Americans in Science (SACNAS) National Diversity in STEM conference, where they were able to share about the results of the NIC and leverage their specialized role to take ownership of the work presented. For the student NIC members, Armando summarized that attending “SACNAS was an incredible experience for me, because I’ve never gotten opportunities like that” (Fa_23, I-1).

Opportunities for students to contribute to the NIC through specific, specialized skills coincided with opportunities for them to grow in leadership (

Figure 4). The NIC had a variety of structures to support student NIC members in taking ownership or leadership over NIC activities. One of the main structures to support this was the introduction of rotating facilitation in the second year of the NIC. In the first year of the NIC, the NIC leaders planned and ran each NIC meeting. However, in the second year, NIC members rotated this responsibility, working in pairs to plan and facilitate meetings. Often, these pairs included one student member. Allie and Sagar described how this opportunity was “particularly empowering” (Sagar, Sp_24, I-1), promoting a message that “everybody is important” (Allie, Fa_24, I-1). Armando reflected on the shift in power, saying, “At first it was kind of scary because I felt like [the NIC leaders] would always lead [the NIC meetings]. It just felt like I’d be a listener and never a planner so it was scary to plan something and make sure work was being done” (Fa_23, I-1). Yet, by the end of Armando’s experience in the NIC, he was able to look at the leadership opportunities as “exciting” (Fa_23, I-1). Together, these experiences illustrate how the NIC’s intentional structures transformed student participation from tentative involvement into confident leadership, fostering a community where students were seen as equal collaborators.

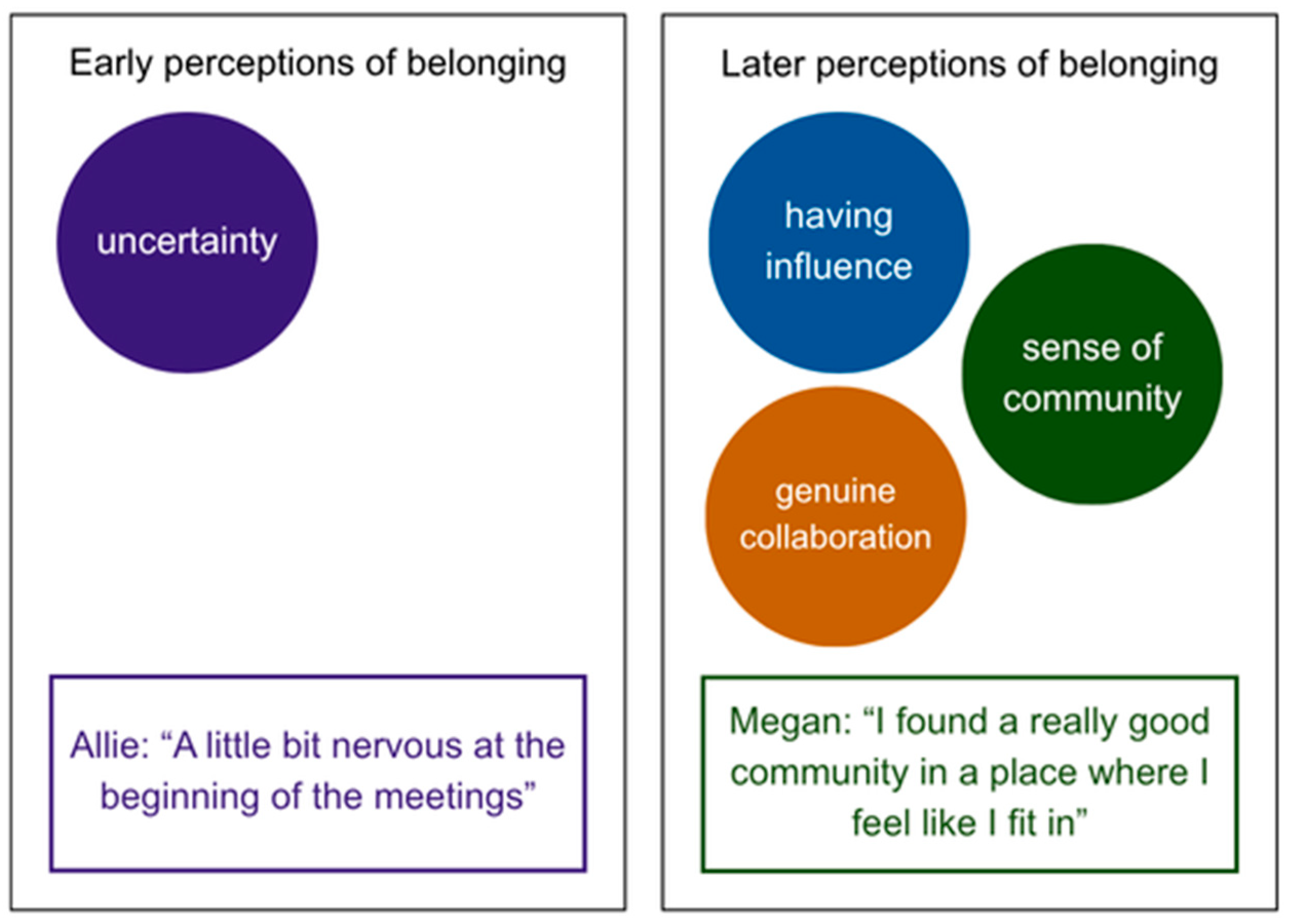

5.4. Shift from Uncertainty to Perceptions of Genuine Collaboration

Many student NIC members initially expressed uncertainty about making meaningful contributions alongside faculty. Megan, for instance, shared that she had “a bit of a hard time fully opening up” (Sp_23, J-2) in her first semester in the NIC, while Allie described being “a little bit nervous at the beginning of the meetings” (Sp_23, I-1). Despite these initial reservations, students emphasized how the NIC’s encouraging environment fostered a sense of inclusion and belonging. Armando noted feeling “well heard” and reassured that his questions and concerns would be addressed (Sp_23, I-1). Megan highlighted how the explicit community norms around participation eased her anxiety over time, while others echoed that the norms helped her to contribute more freely. This validation of student perspectives served both an emotional and intellectual purpose. Sagar observed that the student NIC members were “the ones who actually get to do the acting” (Sp_24, I-1), which helped him recognize the unique value he added to the group. Initially describing themselves as doing “a lot more observing”, by the end of the semester, he reported “taking more of an active role rather than trying to just soak up information” (Sp_24, I-1).

For some students, the NIC served as a bridge to a department that had previously felt distant or intimidating. Allie, though initially nervous about attending AU, appreciated the math department’s inclusivity and its “everybody’s got to start somewhere” attitude (Sp_23, I-1). By the end of the semester, they felt welcomed as a math major (Sp_23, J-1). Even students who initially felt disconnected, like Armando, reflected, “I hope to develop a stronger relationship with the department after my semester with the NIC” (Sp_23, J-1). In this way, the NIC not only fostered belonging within its own community but also catalyzed broader connections to the department.

Over time, students’ feelings of being heard developed into a more robust sense of ownership and influence. By their final semester in the NIC, students described themselves as having a genuine stake in the NIC’s success and feeling empowered to shape its direction—a powerful shift from tentative participation to active leadership (

Figure 5). Megan captured this shift most vividly, explaining that the NIC felt like “the right place for the first time in my life, like I found a really good community in a place where I feel like I fit in” (Fa_24, I-1). For Megan, anxiety that once felt constant—especially in teaching—melted away in the presence of the NIC’s supportive environment. Leading the pre-semester workshop was especially meaningful for Megan: “it was the first time I’ve ever been so instrumental in something of that scale” (Fa_24, J-2). Allie also described this deepened sense of community, likening the NIC to “Tetris blocks fitting together” (Fa_24, I-1) or a “comedy ensemble” that balanced fun with serious collaboration (Fa_24, I-1). What began as an undefined role in her mind, like a “background comedic relief character”, evolved into her finding their “groove” and feeling rooted in her contributions (Fa_24, I-1). Importantly, the NIC became a safe space for personal expression. Allie explained that its inclusive culture allowed them to explore and affirm their pronouns without fear of judgment, underscoring how belonging encompassed both academic and personal identity. Sagar similarly identified a turning point when he first stepped up to be “a more active participant instead of passive” (Fa_24, I-1) after which each meeting became a space and an opportunity for him to contribute to the greater community.

By the final semester of the NIC, a clear collaborative relationship between students and faculty was evident. Gabriel described NIC members as colleagues, emphasizing that faculty actively sought student perspectives and NIC’s structures, like anonymous input, ensured all voices were heard and valued equally. Allie echoed this, recalling that professors—who once seemed like “almighty beings and a bit untouchable”—had become accessible collaborators (Fa_24, I-1), bridging the professor–student gap. Armando, too, noted strengthened departmental ties through collaborative projects and conversations with faculty (Fa_23, J-1). Taken together, NIC student members’ accounts reflected a profound evolution from peripheral participants, tentatively testing their place in the NIC, to confident contributors shaping its goals and outcomes. Initial insecurities about competencies gave way to confidence, agency, and leadership and the deepened sense of belonging led to both professional grounding and personal transformation.

As part of our member checking process, we invited student NIC members to reflect on aspects of their experience that may not have been fully captured in our initial analysis. The following section presents the collective insights of four of the five students represented in this article, offering additional context and nuance to the themes we identified.

6. Students’ Reflections

Each section opens with an italicized glimpse into our internal self-talk, capturing the questions we asked ourselves and the thoughts that shaped our experiences within the NIC.

What if the faculty think we’re criticizing them?

Would being in this group cause any strife in the classroom?

Will what I say in this space affect my grades?

What if the professors are offended? Will I get a bad grade?

Who am I to say anything in this space?

What if I say the wrong thing?

We were all excited about joining a new group and getting involved in the math department in a new way. While we felt positive about joining the NIC, many of us were initially quite anxious about attending meetings. In part because we didn’t know if we would see any familiar faces, or if we even wanted to. We quickly realized the NIC faculty members were also our professors outside of meetings. It was intimidating voicing our opinions about opportunities for improvement within the math department in the presence of faculty members.

Our initial sense of belonging (or lack thereof) in the group was also a source of anxiety. In fact, much of the continued anxiety we felt revolved around finding our roles in the NIC. We didn’t know what we were doing or what was expected of us in the group and at the meetings. One of our biggest concerns was that we would not make meaningful contributions to the NIC’s projects and goals.

Although we entered the NIC feeling nervous about interacting with faculty members outside of the classroom, we found that faculty in the group made genuine efforts to ensure all of us were included. These efforts helped us understand that our contributions were valued. An example of this collegiality included faculty members emphasizing using their first names which meant we had to get comfortable calling our previous professors by their first names. We initially found it difficult to address the faculty members in such an informal way. While this was not a trivial adjustment to make, we found ways to establish connection with our faculty and fellow student NIC members through icebreaker activities and sharing food. These informal means of forming connections went a long way towards helping us feel more comfortable in this space and be more willing to share ideas.

What if everyone hates me?

Why do I want to be here?

Have I been talking for too long? Too much?

Does this person like me?

How can I impress this person?

How honest should I be?

With any group working together it is important to establish norms and expectations early to make sure everyone is heard equally. This idea led us to creating our list of NIC norms we read out at the beginning of each meeting. These norms made it obvious everyone there had the common goal of helping students be successful. It placed a huge emphasis on how important equal partnership and contributions would be while we were working toward this goal. While it might seem cheesy, most meetings opened with an icebreaker question, which eventually became a 5–10 min conversation where we would debate our favorite ice cream combinations, or have check-ins on how everyone was doing. These allowed for us to get comfortable with one another and feel comfortable working together to address the disconnects we saw students facing in classrooms and with the system as a whole. On top of the chance to meet new people and help students, being a part of the NIC was a chance to make connections with other people in the math department that we typically would not have had the chance to. Many of us, including those with experience teaching, wanted to use this as an opportunity to become better educators while others came into this group without a clear reason. With the care we took in ensuring this space was one where we were all viewed as equal partners, it made establishing our goals into an enjoyable process with the intent to make critical transformations to preexisting systems and establish new supports where needed.

How can I use my knowledge and experience to improve/create new supports for students?

What if I fail?

What if I can’t handle the pressure?

What if I don’t do enough? What if I’m not enough?

How will I know if I’m doing a good job? Would anyone tell me if I wasn’t?

As we felt a greater sense of belonging and community in the NIC, we felt more comfortable taking on greater responsibilities. At first, none of us, including the faculty, were really sure what our roles would be. Although there were official leaders of our group, there wasn’t a lot of emphasis placed on those positions during meetings, which allowed for everyone to naturally find their places. There was an interesting balance between all of us figuring out our roles and having guidance from NIC leaders. Drafting our goals allowed us to take ownership of the ideas and plans we were developing. Gradually, we all found a place in the NIC and began volunteering for various tasks. Our increased comfortability within the group influenced the transition from meetings planned and led by the leaders to sharing the responsibility with the group in the form of co-led meetings. Eventually, it also led to us facilitating workshops and presenting posters at different conferences, which were opportunities we did not have prior to joining the NIC.

One of our most intimidating, yet rewarding, projects was a summer math workshop in the weeks leading up to the fall 2024 semester. The NIC agreed it would be a great way to get incoming students ready for classes and help improve their relationship with math, which aligned with our NIC goals. To our surprise, the faculty let us, the students, handle everything. They told us they would be there to support us with whatever we needed, but we were in charge of the workshop. At that moment, it felt a bit like how we imagine a baby bird must feel when its mom pushes it out of the nest to fly for the first time. We had the task of implementing the summer math workshop, with us being the ones in charge of coordinating and planning this workshop. Throughout our planning process, we had several meetings to make sure we had what we needed for in-person and virtual sessions, including Teaching Assistants/Professors to lead mini-lectures, worksheets, a classroom, etc. Throughout our time in the NIC, our level of responsibility increased as well as our ability to take ownership and lead the work of the NIC. We found ourselves capable of far more than merely handling the responsibility; we genuinely flourished under it, which impressed us all.

I know what I’m doing.

I believe in my work.

I believe in myself.

Look how far we’ve come.

How can I use my new skills in other spaces?

How can we share the work we’ve done to inspire others?

I’ve got this. I’m enough.

My thoughts and experiences are valuable and valued.

I’ve found a safe space where I can share my ideas and be heard and respected.

Our increased responsibilities naturally developed our academic and technical skills that we previously didn’t practice. By reflecting on our own experiences while analyzing student data, we developed intuition for data-informed decision making. From brainstorming solutions to problems we identified based on student data, we established an intimate understanding of how data-informed decision making affects larger systems, such as schools or communities. Witnessing the data reflected in our classrooms was an eye-opening experience that helped us appreciate the significance of the discussions our NIC had following data exploration. We learned to look beyond data points and see individual students. For instance, our accomplishments with the student self-placement system included proposing, designing, implementing, and finally, presenting solutions that were informed by student data, both empirical and observational. Addressing the self-placement process also allowed us a peek behind the curtain of how the administration side of academia works together toward a common goal. Having more experience in scientific and academic settings made us feel like we had something to contribute to academic conversations, which helped us be more open to introducing ourselves to and holding full conversations with other scientists.

Being a part of the NIC not only pushed us to gain academic and technical skills, but allowed us to build friendships with each other and our current and former professors. The community that we built became a support system for us. By creating a space where we could be honest and critically thoughtful about the system we had in place for students, we unintentionally fostered a natural sense of community among ourselves. With that sense of community came openness, and genuine excitement to see and speak with one another. We created connections with our fellow NIC members, students and faculty alike, that became friendships outside of our shared space and beyond the lifetime of the NIC. As a result of this sense of comfort with people we might not have made connections with previously, we also felt a new sense of comfort in interacting with other members of faculty. For example, holding a conversation with professors feels more casual than anxious. With all these experiences we had doing things like leading meetings, speaking at conferences, and organizing workshops made us aware of how capable we all were. In many ways, our experiences in the NIC have helped us build confidence even while navigating uncertainty.

7. Discussion

Through this longitudinal analysis, we saw shifts in each construct of belonging across time as the five student participants became more comfortable in the NIC and took on greater responsibility for the group’s success. Additionally, retrospective reflections by four student participants, representing both undergraduate and graduate students, confirm growth in sense of belonging over time and call attention to connections between different constructs that were not captured in our primary analysis. These reflections provided insight into students’ internal dialogue and initial anxiety in joining the NIC, which did not come out as strongly in our earlier analysis. Overall, changes in NIC opportunities supported growth in students’ competencies, which, in turn, reshaped perceptions and expanded motivations.

Initial opportunities such as the NIC’s intentional structures (

Bolick et al., 2025a) supported students in building relationships and contributing to shared goals. Opportunities for belonging that stood out as especially helpful to students early on included icebreaker activities and co-developing community norms that were applied consistently. Aligned with

Matthews’ (

2017) propositions for a genuine partnership, the NIC’s intentional facilitation of community-defined goals highlighted a willingness to embark on a joint endeavor without a predetermined endpoint, paired with dialogue and reflection to facilitate power-sharing. These structures were vital in validating students’ initial competencies—specifically their lived experiences as mathematics students—and positioning their knowledge as integral to the collaborative process of critical reform. As their contributions were consistently valued, student NIC members developed a profound sense of having influence and ownership over the NIC’s direction, forming a basis for a shared investment in the NIC’s collective aims and mission. This expansion of motivations, where individual goals were supported alongside communal motivations, illuminates how belonging might help shape partnerships beyond an “apolitical,” “technocratic,” “business partnership” based in neoliberal ideology (

Peters & Mathias, 2018, p. 185) and into an opportunity for community action.

In their reflections, student members of the research team highlighted how feeling greater belonging in the NIC encouraged them to take on increased responsibilities in developing and implementing the NIC’s goals. Throughout their involvement, student NIC members’ lived experiences were leveraged as competencies for belonging and recognized as valuable for shaping the NIC’s goals. These competencies positioned student members as equal partners within the NIC, reinforcing a culture of agency and reciprocity in which their knowledge was vital to the collaborative process (

Cook-Sather et al., 2014,

2018). Student members’ competencies expanded across time to include larger leadership roles within the NIC, a more nuanced understanding of DEI, and increased self-efficacy in driving the group’s transformations. Thus, student NIC members became instrumental in the work of the NIC, corroborating

Hagerty et al.’s (

1992) findings that an individual’s integral involvement in a system can heighten their sense of belonging. Furthermore, the development of students’ perceived competencies may have countered potential stereotype threat of being perceived as novices within the NIC space. Prior research has shown that such stereotype threat is a known mediating factor that impacts belonging and development of professional identities (

Bailey et al., 2023). Inversely, students in the AU NIC found that they “flourished” when allowed to take leadership over NIC activities.

Finally, the collective nature of the NIC influenced change in students’ perception of belonging. We identified three key shifts in perception that illuminate how students’ sense of belonging deepened over time: (1) initial insecurities over their competencies and resulting hesitation evolved into feeling empowered and having greater agency, (2) the desire for connection transformed into a sense of belonging within the department, and (3) the belief that student input was valued led to feeling a sense of shared ownership of the NIC goals and investment in developing its collective identity. The reflection highlighted, in particular, how being part of the NIC influenced students’ confidence and sense of community in academia and beyond. These trajectories, when seen as parts of a whole, indicate how students moved from feeling like participants to becoming co-conspirators in educational reform efforts through the NIC.

Although the study draws on the experiences of five students from one institution, this qualitative research is designed to generate richly contextualized understandings that can be meaningfully transferred to similar settings. We argue that our research study is not generalizable, but is an example of how the inclusion of students in departmental change efforts impacted their sense of belonging that could be transferred to other institutional or departmental contexts. However, by only looking at one institutional context, we are limiting ourselves to the unique cultural, structural, and programmatic features of that institution. The unique conditions of the institution allowed for the departmental change group to operate, value student opinions, and view students as partners, and we recognize that such conditions may not be present elsewhere. Additionally, the small sample size of students allows for an in-depth understanding of each individual’s experience, but has the potential to not be broadly representative. Yet, we interpret the study as one “existence proof” that through careful and genuine support, students can develop a true sense of belonging and effect change in math departments, NICs, and higher education.

A mathematics department was the context for this study, and the goals of the NIC were to: (1) dismantle the placement system for introductory mathematics courses and (2) create programming that connects students to the utility value of mathematics. Although this study focused on student NIC participants’ sense of belonging, opportunities to engage with mathematics faculty to work toward these goals may have influenced student NIC members’ relationship to mathematics content—how they experience the content, how they teach the content, and how they support other students of mathematics. Examining students’ relationship with mathematics and other outcomes for student NIC members was not the focus of this study, but may be fruitful for future researchers to explore, particularly given findings from other studies about the impact of reform efforts on student leaders involved in those reforms (e.g.,

Breland et al., 2023;

Gomez Johnson et al., 2021;

Gray et al., 2016).