1. Introduction

The graduate employment sector is highly competitive, with employers receiving an average of eighty-six applications per vacancy (

Institute of Student Employers, 2023). Increasing competition for graduate jobs has resulted in employers demanding a wider range of skills from potential employees (

Tight, 2023). Interviews remain a central component of recruitment processes (

Wilk & Cappelli, 2006), and many individuals find the interview process to be anxiety- inducing and stressful (

Constantin et al., 2021;

Schneider et al., 2019), which can negatively affect interview performance (

McCarthy & Goffin, 2004;

Powell et al., 2018).

The competitive nature of the employment market has resulted in 33% of university graduates being unsuccessful in securing highly skilled graduate positions (

GOV.UK, 2023). With 2.9 million students enrolled in UK higher education institutions (

Bolton, 2024), universities face significant pressure to prepare students for job interviews, as qualifications alone do not guarantee successfully securing graduate-level employment (

Tomlinson, 2008). This responsibility is reinforced by the fact that university quality is often assessed through graduate employment statistics (

Cheng et al., 2021).

To support students, universities typically enhance their career development through employability lectures. These sessions help students identify key qualities sought by employers (

Donald et al., 2018), develop self-awareness of their employable attributes and prepare them to respond effectively to interview questions (

Goodwin et al., 2019). Research indicates that interview training improves interview performance ratings (

Huffcutt, 2011), while prior interview experience was positively correlated with an increased likelihood of follow-up interviews or job offers (

Levashina & Campion, 2007). Thus, employability training sessions are likely to benefit students in future recruitment processes.

Beyond lectures, universities increasingly explore alternative approaches to employability training. Examples include implementing industry-led workshops (

Twyford & Dean, 2024), activity-based learning (

Movva et al., 2024), and targeted support for non-native English speakers (

Krishnan et al., 2021). In relation to interview preparation, mock group interviews are particularly effective in enhancing student employability skills (

McWhorter et al., 2024). Online platforms also provide authentic learning environments for developing employability skills.

Martínez-Argüelles et al. (

2023) found that incorporating realistic scenarios improved students’ perceptions of authentic and competence development. These findings raise important questions about whether traditional lectures should be supplemented or replaced by more immersive alternatives, such as Virtual Reality (VR).

VR headsets have become increasingly popular in recent years, with over 20 million headsets being sold for the Meta Quest 2 (

Williams, 2024). Research suggests students often prefer using VR applications, with 82% of students reporting greater engagement in VR environments over a desktop application (

Rogers et al., 2020). Engagement is particularly important for learning as it has been found to be associated with more time spent on learning tasks (

Jensen & Konradsen, 2018;

Loup et al., 2016). VR has also been shown to support the transfer of skills acquired in a virtual environment into the real-world (

Cooper et al., 2021;

Zechner et al., 2023). These advantages may stem from the interactivity and immersion VR provides, both of which have previously been linked to enhanced skill acquisition (

Ghanbaripour et al., 2024;

Hamad & Jia, 2022). Interactivity with the learning environment appears to play a meaningful role, as students show increased engagement with learning environments that are more interactive (

Lampropoulos & Kinshuk, 2024).

Besides engagement and interactivity, a core psychological mechanism that distinguishes VR from traditional learning environments is its ability to induce a strong sense of presence: the feeling of being physically situated in one environment while experiencing another (

Witmer & Singer, 1998). This sense of presence has been suggested to not just be a by-product of VR but is beneficial to a range of core areas for learning. A recent systematic review by

Radianti et al. (

2020) highlighted that an increased sense of presence is linked to both deeper cognitive processing and increased realism of learning tasks.

Ochs and Sonderegger (

2022) also found a sense of presence to be associated with improved attention in distracting contexts. Within a higher education setting,

Rodolico and Hirsu (

2023) demonstrated that the implementation of VR lessons can result in more positive emotions, increased memorability of the learning content, and greater confidence among trainee teachers. This suggests that high presence learning environments can positively influence users’ learning abilities.

Recent research has also highlighted VR’s potential in employability training.

Luo et al. (

2024) demonstrated that VR-based feedback improved interview performance, while

Smith et al. (

2022) found VR job interview training reduced anxiety and enhanced employability skills among students with mental health conditions. However, further research is needed to determine whether the benefits extend to a broader undergraduate student population. Accessibility also remains a challenge, while 93% of students have access to a desktop, only 8% have access to a VR headset (

Student Device Usage Report, 2022). Furthermore, the high cost of VR equipment (

Christou, 2010;

Hamad & Jia, 2022) may deter universities from large-scale adoption without stronger evidence of effectiveness. Therefore, more accessible alternatives, such as desktops, should also be investigated for their effectiveness alongside VR.

Simulated learning environments provide valuable opportunities for experiential learning.

Kolb et al.’s (

2014) theory emphasises learning through concrete experience, reflective observation, abstract conceptualisation and active experimentation. VR and other virtual simulations support this cycle by enabling realistic interview practice (concrete experience), the opportunity to reflect on their own personal performance (reflective observation), generate insights into the development of effective interview strategies (abstract conceptualisation), and the application of these techniques in future scenarios (active experimentation).

The present study examines both student and staff perspectives on three learning environments—3D VR applications, 2D desktop applications and video lectures—to evaluate their perceived effectiveness in developing interview skills. To provide clarity, the research is divided into two studies: the first explores students’ attitudes toward each environment, while the second investigates staff perceptions of their effectiveness. In Study 1, students were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: VR, desktop simulation, or a lecture-based group discussion using video application interviews with the teacher present. Following training, participants completed a survey consisting of the Immersive Presence Questionnaire (

Witmer & Singer, 1998), the User Experience Questionnaire Shortened (UEQ-S) (

Schrepp et al., 2017) and an Employability Skills Questionnaire created by the researchers. It was hypothesised that VR participants would score higher across all three measures. In Study 2, staff experienced 10 min samples of each environment and completed the same questionnaires. After the final session, staff ranked the three approaches in order of preference for interview skills development.

2. Student Method

2.1. Participants

A total of 42 psychology students (9 males and 33 females) participated in the study. This ratio of male to female participants is broadly representative of the gender distributions found in psychology student cohorts (

Calia & Kanceljak, 2023). The mean age was 19 (SD = 2.15; age range = 18–29). Of these, 18 students were assigned to the VR condition, 10 to the desktop condition and 14 to the lecture condition. Eligibility criteria required participants to be enrolled at the University of Liverpool and have normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing (e.g., glasses). Recruitment was primarily conducted through an internal scheme in which students received course credit for participation. Additional volunteers were recruited via an email advertisement. All participants were entered into a prize draw to win one of twenty £10 Amazon gift cards. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the University of Liverpool Ethics Committee (reference number 12380).

2.2. Design

A between-subjects design was employed, with the learning environment (3D VR, 2D desktop or video-focused lecture) as the independent variable. The dependent variables were scores on the Employability Skills, the User Experience Questionnaire Shortened (UEQ-S) and the Immersive Presence Questionnaires.

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. VR and Desktop Simulation

The simulation was created by

Bodyswaps (

2019) and involved participants taking part in the “Job Interview: Landing a perfect job” scenario from the “Employability & Job Interview” module. This simulation guided participants through interview preparation, including strategies for effective responses, understanding the purpose of interviews, and receiving feedback on interview question responses. Participants interacted with the simulation using a combination of controller/keyboard input and verbal responses via a microphone (integrated into the VR headset or headphones in the desktop condition). The VR simulation was presented using a Meta Quest 2 headset. An example of an interview simulation scenario is illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.3.2. Video Focused Lecture

In line with the VR and desktop simulations, the lecture aimed to teach students the skills required to perform effectively in interviews. The sessions emphasised how to structure responses to interview questions and included several videos of mock interviews that demonstrated both strengths and weaknesses. A researcher facilitated a discussion with participants, allowing them to identify aspects the interviewees performed well on and areas that required improvement.

2.3.3. Employability Skills Questionnaire

The Employability Skills Questionnaire was developed by the researchers to measure students’ perceptions of the employability skills development process. Participants rated their agreement with three items on a scale from 0 to 10. For example, one item asked, “To what extent do you think you have developed transferable employability skills with the application?”. Higher overall scores indicated that participants perceived the learning approach as more useful for developing employability skills.

Each item was designed to capture key dimensions of employability skills development. The first item assessed the extent to which participants perceived that they had developed transferable employability skills, directly addressing the primary learning objective of the training session. The second item evaluated the enjoyment of learning the employability skills, which was included as it has been previously linked to increased concentration and absorption of content (

Lucardie, 2014). Importantly, the third item measured levels of active engagement with the learning environment, which has been shown to improve outcomes compared to passive approaches such as lectures (

Freeman et al., 2014). A copy of the Employability Skills Questionnaire is provided in

Appendix A.

2.3.4. User Experience Questionnaire Short (UEQ-S)

The UEQ-S scale was developed by

Schrepp et al. (

2017) to assess users’ experience and employs a 7-point Likert scale between opposing descriptors. For example, it ranges from a negative evaluation (e.g., confusing) to a positive evaluation (e.g., clear). The questionnaire comprises two dimensions: pragmatic and hedonic. Pragmatic items measure interaction qualities related to task completion and goal achievement. Hedonic items, on the other hand, measure aspects of pleasure and enjoyment during use. Participants responded to eight items, with higher scores reflecting a more positive user experience. A copy of the UEQ-S is provided in

Appendix B.

2.3.5. Immersive Presence Questionnaire

A shortened version of the

Witmer and Singer (

1998) Immersive Presence questionnaire was administered to measure the extent to which participants experienced the simulated environment rather than the physical world. Items included questions such as “How natural did your interactions with the application seem?”. Questions that could not be adapted to the lecture environment condition (i.e., “How compelling was your sense of objects moving through space?”) were excluded. A copy of the Immersive Presence Questionnaire is provided in

Appendix C.

2.4. Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants completed a demographic questionnaire. Once participants were taught how to use the relevant equipment, they then engaged in one of the three learning environments (VR, desktop simulation or lecture) for approximately 30 min. Following the training session, participants completed the Employability Skills, UEQ-S, Immersive Presence Questionnaires and an open-ended item, providing feedback on their experience before being debriefed.

3. Student Results

3.1. Employability Skills

The employability questionnaire was evaluated for internal consistency using McDonald’s Omega. The Omega hierarchical (ωh = 0.05) indicated that 5% of the variance was attributable to a general factor, while the Omega Total (ωt = 0.8) demonstrated good internal consistency. Consequently, all three items were retained for analysis. Item factor loadings are in

Figure 2. A between-subjects ANOVA examined the effect of the learning environment on employability skills. Results indicated no significant effect,

F(2, 39) = 0.35,

p = 0.706, ηp

2 = 0.02, 95% CI [0.00, 1.00].

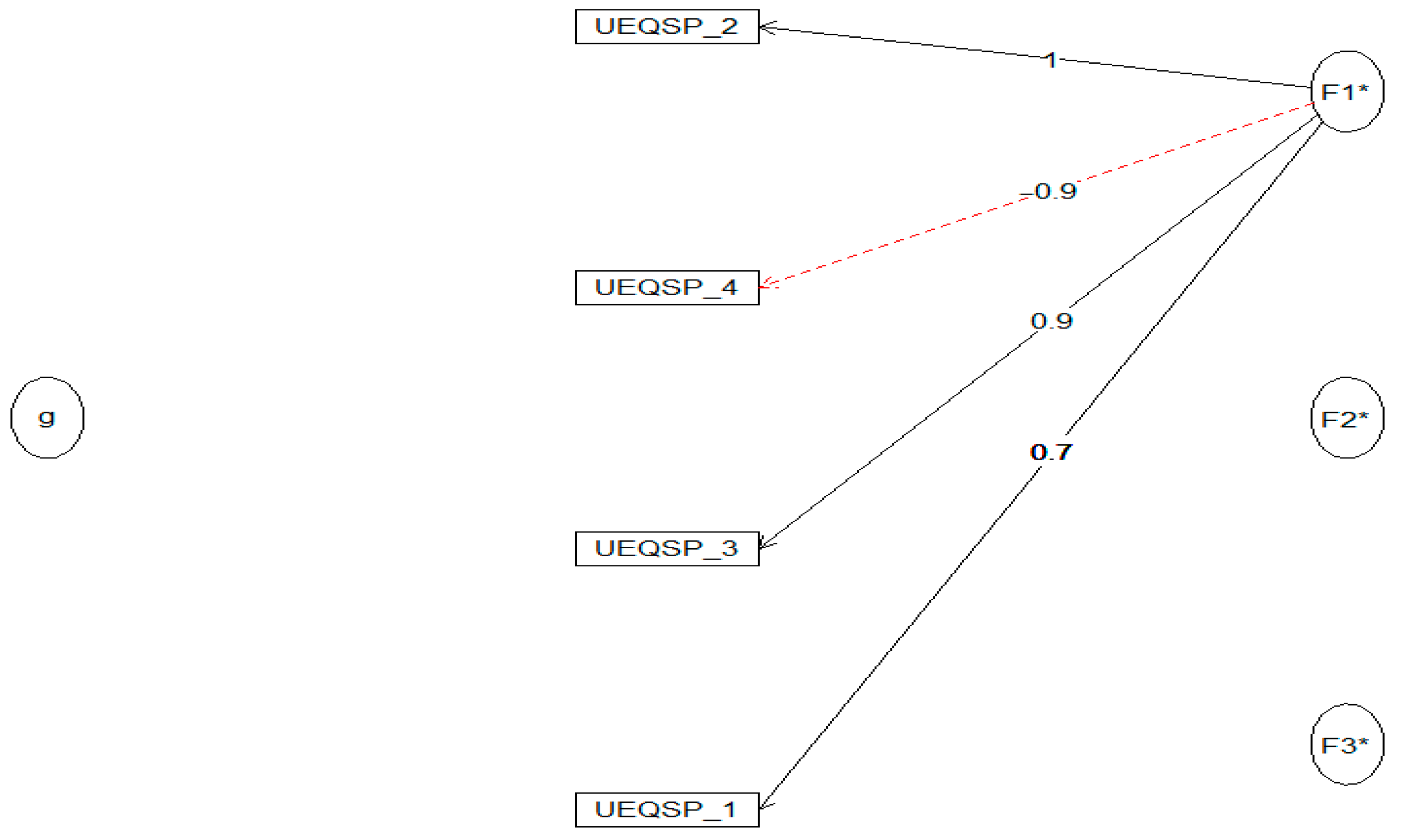

3.2. UEQ-S Pragmatic

Internal consistency of the UEQ-S pragmatic scale was assessed using McDonald’s Omega. The Omega hierarchical (ωh = 0.03) suggested that 3% of the variance was explained by a general factor, while the Omega Total (ωt = 0.74) indicated acceptable internal consistency. All items were included in the analysis. Factor loadings are shown in

Figure 3.

A between-subjects ANOVA tested the effect of the learning environment on pragmatic scores. No significant differences were observed, F(2, 38) = 0.26, p = 0.773, ηp2 = 0.01, 95% CI [0.00, 1.00].

3.3. UEQ-S Hedonic

McDonald’s Omega was conducted to evaluate the internal consistency of the UEQ-S hedonic scale. The Omega hierarchical (ωh = 0.17) indicated that 17% of the variance was attributable to a general factor, while the Omega Total (ωt = 0.84) demonstrated good reliability. All items were retained. Factor loadings are presented in

Figure 4. A between-subjects ANOVA explored the effect of the learning environment on hedonic scores. No significant effect was found,

F(2, 37) = 0.44,

p = 0.650, ηp

2 = 0.02, 95% CI [0.00, 1.00].

3.4. Immersive Presence

A McDonald’s Omega demonstrated strong internal consistency for the immersive presence questionnaire. The Omega hierarchical (ωh = 0.70) indicated that 70% of the variance was explained by a general factor, with the Omega Total (ωt = 0.89) confirming good internal consistency. All items were retained. Factor loadings are shown in

Figure 5. A between-subjects ANOVA assessed the effect of the learning environment on immersive presence scores. Results indicated no significant effect,

F(2, 38) = 0.60,

p = 0.554, ηp

2 = 0.03, 95% CI [0.00, 1.00].

3.5. Descriptive Statistics

Mean scores and standard deviations for all questionnaires (employability skills, UEQ-S, and immersive presence questionnaires) across learning environments are presented in

Table 1.

4. Discussion for Student Sample

The first study explored students’ attitudes towards three learning environments, VR, desktop and traditional lecture using videos, for teaching undergraduate students’ employability skills, specifically job interview skills. Contrary to the initial hypothesis, there were no significant differences between across conditions in terms of employability skills developed, user experience or sense of presence. Although the statistical analyses did not reveal meaningful effects, the findings nonetheless provide valuable pedagogical insights. Prior research suggests that students are often more motivated by interactive and engaging learning environments (

Lampropoulos & Kinshuk, 2024). In this context, the integration of VR or desktop learning applications may improve attendance and participation. This interpretation is supported by participant feedback, with several students describing the VR condition as “engaging as it was something different”.

5. Staff Introduction

While it is valuable to explore student perspectives on effective learning environments for employability skill development, it is equally important to assess these from the viewpoint of staff, who typically have greater interview experience and teach this topic to undergraduate students. To secure their role, staff members will have participated in job interviews as interviewees and likely have additional experience as interviewers. This dual perspective positions them well to critique interview-based learning environments and techniques by drawing direct comparisons with their own experiences. Furthermore, as staff are responsible for delivering employability sessions to students, their feedback provides critical insight into the practicality and feasibility of implementing such learning environments.

The purpose of this second study was therefore to investigate which learning environment university staff perceive as most effective for teaching employability skills. Staff engaged with all three learning environments (VR, desktop, and lecture) and completed the same questionnaires as the student sample after each condition. Consistent with the first study, it was hypothesised that participants would report higher scores on the Employability Skills Questionnaire, UEQ-S and the Immersive Presence Questionnaire in the VR condition compared to the desktop or lecture conditions.

6. Staff Methods

6.1. Staff Sample

Twelve staff members (4 males, 7 females and 1 non-binary) participated in the study. The mean age was 27 (SD = 5, range = 23–40). All participants were psychology staff at the University of Liverpool with experience teaching undergraduate students, and all reported normal or corrected-to-normal vision and hearing (e.g., glasses). Recruitment was conducted via opportunity sampling, with staff approached individually and invited to participate. As an incentive, participants were entered into the same prize draw as those participating in Study 1. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Liverpool ethics committee (reference number 12380).

An a priori power analysis using G*Power 3.1.9.7 analysis (

Faul et al., 2009) determined the required sample size. For a within-subjects ANOVA with three measurements, a large effect size (Cohen’s f of 0.50) and power of 0.8, the analysis indicated a minimum of 9 participants. The final sample of 12 participants, therefore, exceeded this requirement.

6.2. Design

A within-subjects design was employed. The independent variable was learning environment (VR, desktop or lecture), and the dependent variables were scores on the Employability Skills, UEQ-S, Immersive Presence, and Environment Preference questionnaires.

6.3. Materials

The same materials used in Study 1 were administered to staff. In addition, a single-item measure was developed to assess staff preferences for a learning environment. Participants were asked: “Please rank the following learning approaches from most preferred (top) to least preferred (bottom) method for teaching students’ employability skills”. The order of response options was randomised. Lower scores indicated a stronger preference for a given environment.

6.4. Procedure

Following informed consent, participants completed a demographic questionnaire. They then engaged with each of the three learning environments (VR, desktop, and lecture) for 10 min each. This duration was deemed sufficient to familiarise staff with the content without requiring full exposure to the entire simulation/lecture. The order was evenly counterbalanced across participants.

After each condition, participants completed the Employability Skills, UEQ-S, and Immersive Presence questionnaires. This process was repeated until all three environments had been experienced. Once participants had finished the final questionnaire, they were then asked to rank the three learning environments from most preferred (top) to least preferred (bottom). They were then presented with an open-ended text box asking for feedback regarding the learning environments. Finally, participants were debriefed. The study lasted approximately 45 min.

7. Staff Results

7.1. Employability Skills Scale

A McDonald’s Omega was conducted to assess the internal consistency of the employability skills questionnaire. The Omega hierarchical (ωh = 0.05) indicated that 5% of the variance was attributable to a general factor, while the Omega Total (ωt = 0.89) demonstrated good internal consistency. All items were therefore retained for analysis. Item factor loadings are presented in

Figure 6.

A repeated measures ANOVA found a significant main effect of learning environment (lecture, desktop or VR) on employability skills, F(2, 22) = 7.25, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.40, 95% CI [0.11, 1.00]. Post hoc comparisons using a Bonferroni correction showed that employability skills scores were significantly higher in the VR environment (M = 25.4, SE = 1.3) compared to the desktop environment (M = 18.6, SE = 1.3, p < 0.001). However, there were no significant differences between either the desktop and lecture (M = 21.3, SE = 1.3, p = 0.426) or the VR and lecture conditions (p = 0.102).

7.2. UEQ-S Pragmatic

A McDonald’s Omega was conducted to assess the internal consistency of the UEQ-S pragmatic scale. The Omega hierarchical (ωh = 0.73) indicated that 73% of the variance in the UEQS pragmatic section of the UEQ-S questionnaire was due to a general factor. The Omega Total (ωt = 0.76) highlighted that the scale has an acceptable internal consistency. All items were retained. Factor loadings shown in

Figure 7.

A repeated measures ANOVA found a non-significant main effect of learning environment on UEQ-S Pragmatic scores, F(2, 22) = 1.15, p = 0.336, ηp2 = 0.09, 95% CI [0.00, 1.00].

7.3. UEQ-S Hedonic

A McDonald’s Omega was conducted to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire. An Omega hierarchical (ωh = 0.83) indicated that 83% of the variance in the hedonic section of the UEQ-S questionnaire was due to a general factor. The Omega Total (ωt = 0.98) highlighted that the scale has excellent internal consistency. All items were retained, with factor loadings presented in

Figure 8.

A repeated measures ANOVA found a significant main effect of the learning environment on UEQ-S Hedonic scores, F(2, 22) = 31.12, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.74, 95% CI [0.55, 1.00]. A post hoc comparison using a Bonferroni correction found that the VR condition (M = 2.40, SE = 0.32) had significantly higher UEQ-S scores compared to both the desktop (M = 0.08, SE = 0.32, p < 0.001) and lecture (M = 0.21, SE = 0.32, p < 0.001) conditions. However, there was no significant difference between the desktop and lecture conditions (p = 1.00).

7.4. Presence

A McDonald’s Omega was conducted to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire. An Omega hierarchical (ωh = 0.71) indicated that 71% of the variance in the presence questionnaire were due to a general factor. The Omega Total (ωt = 0.98) highlighted that the scale has an excellent internal consistency. All items were retained, with factor loadings shown in

Figure 9.

A repeated measures ANOVA found a significant main effect of learning environment on presence scores, F(2, 20) = 6.09, p = 0.009, ηp2 = 0.38, 95% CI [0.08, 1.00]. Post hoc tests using a Bonferroni correction showed that VR presence scores (M = 22.0, SE = 1.38) were significantly higher than the desktop condition (M = 16.0, SE = 1.38, t(20) = 2.82, p = 0.031). The lecture condition (M = 22.6, SE = 1.35) was also significantly higher compared to the desktop condition (t(20) = 3.21, p = 0.013). However, there was no significant difference between the VR and lecture conditions (t(20) = 0.29, p = 1.00).

7.5. Rank Conditions

The ranked conditions were analysed using a repeated measures ANOVA to investigate whether participants indicated a significant preference for learning in any of the three learning environments. Participants ranked each environment from 1 (most preferred) to 3 (least preferred), such that a lower mean rank indicates a stronger preference. The analysis revealed a significant main effect of learning environment on preference rankings, F(2, 20) = 4.41, p = 0.026, ηp2 = 0.31, 95% CI [0.03, 1.00]. Post hoc tests using a Bonferroni correction revealed a greater preference for the lecture condition (M = 1.64, SE = 0.22) compared to the desktop condition (M = 2.64, SE = 0.22, t(20) = 2.68, p = 0.043). However, there was no significant difference between the VR (M = 1.73, SE = 0.22) and the desktop (t(20) = −2.44, p = 0.072) or lecture conditions (t(20) = 0.24, p = 1.00).

8. Staff Discussion

This second study explored staff perspectives on teaching employability skills across three learning environments (VR, desktop and lecture). Results indicated that staff rated VR as a more effective learning environment than the desktop condition for employability skills development and presence. In the UEQ-S, VR was perceived as more enjoyable than both the desktop and lecture conditions. When ranking the learning environments, staff indicated a greater preference for lectures over a desktop unit, but there were no significant differences between the VR condition and either of the other conditions. Overall, staff expressed a stronger preference for VR, supported by comments such as “PC was good; however, [it was] not as good as VR”.

9. General Discussion

The current studies examined whether using a 3D VR application could enhance undergraduate students’ interview skills development compared to a 2D desktop application or a video-focused lecture presentation. Findings from the student sample in the first study revealed no significant differences across conditions, suggesting that students did not perceive one environment as superior in terms of employability skills, user experience or sense of presence. One possible explanation for these findings is that students, often inexperienced with job interviews, may lack the evaluative capacity to critically assess the effectiveness of different training environments.

To address this limitation, the second study included staff participants, who possess greater experience with interview processes and teaching on employability skill development sessions. Staff perceived VR as more effective for teaching employability skills, providing a more enjoyable experience than lectures and desktop simulations, as well as being more immersive (sense of presence) than the desktop condition. These findings are further supported by staff feedback, with participants saying that they would “actually look forward to the VR sessions” and “thought the VR was good in the sense that it was very engaging and immersive”. A potential explanation for these findings is that staff may prefer using a more immersive learning experience for teaching employability skills content. This preference would align with research that indicates that an increased sense of presence is linked with increased attention to learning content (

Ochs & Sonderegger, 2022). It seems that staff have noticed the benefits of employability skills teaching from this perspective due to their previous experience. One persistent challenge with lecture-based employability training is poor student attendance (

Bati et al., 2013;

Traphagan et al., 2009). Although interview training is associated with improved outcomes, such as higher interview ratings (

Huffcutt, 2011), students would need to attend these employability sessions to experience this benefit. Staff feedback highlighted VR’s novelty and appeal, with one participant noting: “VR approach is a novel approach that I think would appeal to undergrads”. This suggests that VR may encourage greater attendance and engagement, thereby enhancing employability skill development.

One potential explanation for the differing findings between the staff and student perspectives may lie in the nature of the learning task. Cognitive Load Theory suggests that multimedia learning environments (i.e., videos, 2D desktop and 3D VR applications) require learners to select, organise, and integrate visual and verbal information into their short- and long-term memory (

Mayer & Moreno, 2002,

2003). The short term memory consists of the three additive forms of cognitive load: intrinsic load, which depends on task complexity and learner expertise; extraneous load, which is based on the design and presentation of the learning materials; and germane load, which reflects the mental effort users devote to processing the information and integrating it with the previous existing cognitive schema (

Kalyuga, 2009;

Park et al., 2011). From this perspective, the employability learning task may have imposed a particularly high cognitive load on students, who often lack prior interview experience, were required to navigate unfamiliar learning environments (VR and desktop simulations), and had to process visual and verbal information simultaneously. These cumulative cognitive demands may have constrained students’ abilities to reflect on learning outcomes, thereby limiting their perception of gains in employability skills despite engagement with the learning context. Staff evaluations, on the other hand, are shaped by expertise (i.e., personal job interview experience and from the teaching experience on this topic), pedagogical perspectives (i.e., teaching this topic to undergraduate students) and reduced cognitive load (i.e., awareness of the learning task), enabling them to see VR’s potential for employability training. Students, facing higher cognitive demands and limited prior experience, may struggle to perceive these benefits, focusing instead on usability challenges and immediate outcomes.

An additional factor that may help explain the discrepancy between student and staff evaluations is metacognition, defined as learners’ awareness of their own cognitive processes (

Martinez, 2006). A learning environment is considered effective, when it extends beyond user engagement; learners can monitor their own understanding, evaluate their performance and reflect on their learning strategies (

Zimmerman, 2002). In the context of interview training, this involves recognising which responses are appropriate for a given situation, identifying weaknesses in communication skills, and understanding how feedback can be applied to improve future performance. Given their limited prior interview experience, students may possess underdeveloped metacognitive skills in this domain. Consequently, they may struggle to accurately assess whether the learning environment enhances their employability skills, even when learning has occurred. This limitation may help explain the absence of significant differences between the learning environments for the student sample. By contrast, staff members are likely to have well-developed metacognitive schemas related to interviews, informed by both personal experience and pedagogical practice. This expertise enables them to more accurately evaluate the learning potential of each of environment, thereby accounting for the differences observed between student and staff evaluations.

10. Implications and Applications

The findings have important implications for curriculum design in higher education. While VR was only significantly more effective than lectures in terms of user enjoyment, its overall pedagogical value is evident. Rather than replacing lectures, VR interview simulations could be integrated as supplementary workshop activities, enabling students to practice interview skills in short, focused sessions. The portability of VR headsets also offers opportunities for independent practice at home, allowing students to revisit scenarios, refine responses, and progress at their own pace. This flexibility was echoed in student feedback: “VR was a great teaching approach as it gives students a task to, in effect, have lots of one-on-one time, without actually having to have lots of staff to give them this time”.

While VR shows pedagogical promise, large scale implementation remains limited due to cost and accessibility. Given the large student population, it would not be sustainable to provide every student with the opportunity to individually access the employability simulation. A more feasible approach would be to integrate VR as a complementary tool alongside lectures rather than implementing it as a full replacement. This approach is reflected in staff feedback, with some staff voicing concerns that the VR may not be entirely feasible to implement.

From a digital pedagogy perspective, VR and desktop learning simulation environments encouraged active learning, which aligns closely with the four key elements of experiential learning (

Kolb et al., 2014). By placing students in a realistic interview scenario, these environments provide concrete interview experiences and opportunities for reflection on their own personal performance. These elements are difficult to replicate in a traditional lecture environment, which primarily focus on the transmission of information rather than the rehearsal of skills. Thus, simulated environments represent valuable tools for enabling safe, interactive engagement with employability content.

This study makes three key contributions to the literature on immersive learning and employability training in higher education. First, it reveals a divergence in perceived effectiveness between students and staff in learning environments. Whilst staff emphasised the benefits of VR for employability skills, presence and user experience, these findings were not reflected in student evaluations. This suggests that perceptions of immersive environments are shaped by users’ expertise and prior experience, extending earlier work on immersive learning technologies. Second, by directly comparing VR with desktop simulations, the study demonstrated that immersion alone does not necessarily enhance perceived learning effectiveness. Third, by including both student and staff samples, the study addresses a notable gap in the literature, which has largely relied on student perspectives while overlooking staff insights. These findings underscore the importance of incorporating expert viewpoints when evaluating immersive environments as potential pedagogical tools.

11. Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. Some participants reported discomfort when speaking with other people in the room. However, as students would likely have to complete the simulation task in a room with other students, this, unfortunately, is likely to be unavoidable. A potential solution that future studies may wish to investigate is whether these findings are consistent when participants are given access to the VR and desktop simulation for use in their own environment.

Moreover, employability training varies across universities, raising questions about generalisability. Future studies should examine both student and staff perspectives across institutional contexts. Additionally, reliance on self-report questionnaires introduces the possibility of bias. More objective measures, such as performance in mock interviews, could provide stronger evidence of training effectiveness.

Furthermore, VR remains a novel technology, with only few students having access to a VR headset as discussed in the. This may be problematic, as it raises the question of whether students’ ratings on the user experience questionnaire could have been inflated by the novelty of the equipment rather than by the potential effectiveness of a more immersive learning environment. Longitudinal research is needed to determine whether VR’s perceived benefits persist once the novelty wears off.

The employability skills questionnaire, whilst resulting in significant differences for the staff sample, only consisted of three items. Despite the McDonald’s Omega indicating good internal consistency, the items resulted in poor unidimensionality of the items (hierarchical omega of 0.05). Further research should examine the impact of VR on employability skills using a well-established questionnaire, enabling a more robust assessment of how different learning environments can impact employability skills. Furthermore, the assessment of the employability skills could be complemented with the inclusion of behavioural outcomes in the form of video-recorded mock interviews.

It should be noted that whilst staff perceived the VR learning environment to be effective for teaching employability skills, participants’ performance was not assessed in a real-world setting. Future research should investigate the direct applications of the learning environments on participants’ ability to perform effectively in a real-world interview.

12. Conclusions

In summary, while students did not express a clear preference for any learning environment, staff demonstrated a significant preference for using a VR simulation over a desktop environment. Particularly in terms of employability skill development, user enjoyment, and presence. Although VR was not significantly more effective than lectures for skill acquisition, its novelty and immersive qualities may enhance student engagement and attendance. Based on these findings, universities should consider integrating VR into their employability training as a supplementary tool, offering students flexible, interactive opportunities to develop interview skills alongside traditional lecture-based instruction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.B. and M.L.; Methodology, M.B., M.L. and G.M.; Validation, M.B. and M.L.; Formal Analysis, M.B. and G.M.; Investigation, M.B. and M.L.; Resources, M.B. and M.L.; Data Curation, M.B. and G.M.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.B., M.L., G.M. and C.B.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.B., M.L., G.M. and C.B.; Supervision, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Institute of Population Health at the University of Liverpool through the Research and Scholarship Support scheme and by BodySwaps through Meta’s Immersive Soft Skills Education Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been approved by the Ethics Review Panel of University of Liverpool (reference number 12380), with the approval date of 9 March 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following people for their assistance with data collection for the study: Yasmine Abbott-Smith, Jasmine Ahmed, Sara Allen, Eleanor Anderson, Jess Anderson, Lottie Anderson, Meg Anderson and Laura Carpenter.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Employability Skills Questionnaire

To what extent do you think that you have developed transferable and employability skills with the application (0 = not at all, 10 = very much likely)

To what extent did you enjoy learning about developing transferable and employability skills? (0 = no enjoyment, 10 = extremely enjoyable)

To what extent did you think the learning experience encouraged you to be active and engaged (0 = not at all, 10 = very engaging)

Appendix B

User Experience Questionnaire Shortened (UEQ-S)

I found the simulation to be…

| obstructive | | | - | - | - | - | - | | | supportive |

| complicated | | | - | - | - | - | - | | | easy |

| inefficient | | | - | - | - | - | - | | | efficient |

| clear | | | - | - | - | - | - | | | confusing |

| boring | | | - | - | - | - | - | | | exciting |

| not interesting | | | - | - | - | - | - | | | interesting |

| conventional | | | - | - | - | - | - | | | inventive |

| usual | | | - | - | - | - | - | | | leading edge |

Appendix C

Presence Questionnaire

Whilst you were in the learning environment…

How natural did your interactions with the application seem? (1 = not natural–7 = very natural)

How much did the visual aspects of the application involve you? (1 = not involved–7 = very involved)

How natural was the mechanism which controlled movement through the application? (1 = not natural–7 = very natural)

How compelling was your sense of human objects being through the application? (1 = not compelling–7 = very compelling)

How much did your experience in the simulation seem consistent with your real-world experience? (1 = not consistent–7 = very consistent)

How compelling was your sense of moving around inside the application (1 = not compelling–7 = very compelling)

How involved were you in the application experience? (1 = not involved–7 = very involved)

References

- Akman, E., & Çakır, R. (2023). The effect of educational virtual reality game on primary school students’ achievement and engagement in mathematics. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(3), 1467–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bati, A. H., Mandiracioglu, A., Orgun, F., & Govsa, F. (2013). Why do students miss lectures? A study of lecture attendance amongst students of health science. Nurse Education Today, 33(6), 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterley, M., & Meyer, G. (2025). Beyond reality—The influence audio-visual-haptic training has on sequence learning in a VR and real-world environment. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodyswaps. (2019). Bodyswaps [VR and Desktop Application]. Available online: https://bodyswaps.co/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Bolton, P. (2024). Higher education student numbers. House of Commons Library. Available online: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-7857/CBP-7857.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Buttussi, F., & Chittaro, L. (2020). A comparison of procedural safety training in three conditions: Virtual reality headset, smartphone, and printed materials. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 14(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calia, C., & Kanceljak, D. (2023). Diversity and inclusion in UK psychology: A nationwide survey. Clinical Psychology Forum, 1(369), 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M., Adekola, O., Albia, J., & Cai, S. (2021). Employability in higher education: A review of key stakeholders’ perspectives. Higher Education Evaluation and Development, 16(1), 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christou, C. (2010). Affective, interactive and cognitive methods for e-learning design. In Virtual reality in education (pp. 228–243). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, K. L., Powell, D. M., & McCarthy, J. M. (2021). Expanding conceptual understanding of interview anxiety and performance: Integrating cognitive, behavioral, and physiological features. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 29(2), 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N., Millela, F., Cant, I., White, M. D., & Meyer, G. (2021). Transfer of training-virtual reality training with augmented multisensory cues improves user experience during training and task performance in the real world. PLoS ONE, 16(3), e0248225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, W. E., Ashleigh, M. J., & Baruch, Y. (2018). Students’ perceptions of education and employability. Career Development International, 23(5), 513–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(23), 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanbaripour, A. N., Talebian, N., Miller, D., Tumpa, R. J., Zhang, W., Golmoradi, M., & Skitmore, M. (2024). A systematic review of the impact of emerging technologies on student learning, engagement, and employability in built environment education. Buildings, 14(9), 2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, J. T., Goh, J., Verkoeyen, S., & Lithgow, K. (2019). Can students be taught to articulate employability skills? Education + Training, 61(4), 445–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOV.UK. (2023). Graduate labour market statistics. Available online: https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/graduate-labour-markets (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Hamad, A., & Jia, B. (2022). How virtual reality technology has changed our lives: An overview of the current and potential applications and limitations. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffcutt, A. I. (2011). An empirical review of the employment interview construct literature. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 19(1), 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of Student Employers. (2023). Robust yet competitive graduate labour market. Available online: https://insights.ise.org.uk/home_featured/blog-robust-yet-competitive-graduate-labour-market/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Jensen, L., & Konradsen, F. (2018). A review of the use of virtual reality head-mounted displays in education and training. Education and Information Technologies, 23(4), 1515–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyuga, S. (2009). Knowledge elaboration: A cognitive load perspective. Learning and Instruction, 19(5), 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A., Boyatzis, R. E., & Mainemelis, C. (2014). Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. In Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles (pp. 227–247). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan, I. A., Ramalingam, S., Kaliappen, N., Uthamaputhran, S., Suppiah, P. C., Mello, G. D., & Paramasivam, S. (2021). Graduate employability skills: Words and phrases used in job interviews. Australian Journal of Career Development, 30(1), 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G., & Kinshuk. (2024). Virtual reality and gamification in education: A systematic review. Educational Technology Research and Development, 72, 1691–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levashina, J., & Campion, M. A. (2007). Measuring faking in the employment interview: Development and validation of an interview faking behavior scale. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1638–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loup, G., Serna, A., Iksal, S., & George, S. (2016). Immersion and persistence: Improving learners’ engagement in authentic learning situations. In European conference on technology enhanced learning (pp. 410–415). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lucardie, D. (2014). The impact of fun and enjoyment on adult’s learning. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 142, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X., Wang, Y., Lee, L.-H., Xing, Z., Jin, S., Dong, B., Hu, Y., Chen, Z., Yan, J., & Hui, P. (2024). Using a virtual reality interview simulator to explore factors influencing people’s behavior. Virtual Reality, 28(1), 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M. E. (2006). What is metacognition? PDK International, 87(9), 696–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Argüelles, M. J., Plana-Erta, D., & Fitó-Bertran, À. (2023). Impact of using authentic online learning environments on students’ perceived employability. Educational Technology Research and Development, 71(2), 605–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2002). Aids to computers-based multimedia learning. Learning and Instructional, 12(1), 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E., & Moreno, R. (2003). Nine ways to reduce cognitive load in multimedia learning. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J., & Goffin, R. (2004). Measuring job interview anxiety: Beyond weak knees and sweaty palms. Personnel Psychology, 57(3), 607–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhorter, R. R., Johnson, G., Delello, J., Young, M., & Carpenter, R. E. (2024). We have talent: Mock group interviewing improves employer perceived competence on hireability. Journal of Education for Business, 99(5), 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movva, S., Basireddi, R., Bolleddu, S. N., Pagidipati, B., Lakshmi, K. S., Kathula, D., & Anumula, V. S. S. (2024). An empirical study on enhancing interview skills through activity based learning at graduation level. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 14(9), 2671–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, C., & Sonderegger, A. (2022). The interplay between presence and learning. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 3, 742509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B., Moreno, R., Seufert, T., & Brünken, R. (2011). Does cognitive load moderate the seductive details effect? A multimedia study. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(1), 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D. M., Stanley, D. J., & Brown, K. N. (2018). Meta-analysis of the relation between interview anxiety and interview performance. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 50(4), 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radianti, J., Majchrzak, T. A., Fromm, J., & Wohlgenannt, I. (2020). A systematic review of immersive virtual reality applications for higher education: Design elements, lessons learned, and research agenda. Computers & Education, 147, 103778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodolico, G., & Hirsu, L. (2023). Virtual Reality in education: Supporting new learning experiences by developing self-confidence of Postgraduate Diploma in Education student-teachers. Educational Media International, 60(2), 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S. L., Hollett, R., Li, Y. R., & Speelman, C. P. (2020). An evaluation of virtual reality role-play experiences for helping-profession courses. Teaching of Psychology, 49(1), 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L., Powell, D. M., & Bonaccio, S. (2019). Does interview anxiety predict job performance and does it influence the predictive validity of interviews? International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 27(4), 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrepp, M., Hinderks, A., & Thomaschewski, J. (2017). Design and evaluation of a short version of the user experience questionnaire (UEQ-S). International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence, 4(6), 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M. J., Smith, J. D., Blajeski, S., Ross, B., Jordan, N., Bell, M. D., McGurk, S. R., Mueser, K. T., Burke-Miller, J. K., Oulvey, E. A., Fleming, M. F., Nelson, K., Brown, A., Prestipino, J., Pashka, N. J., & Razzano, L. A. (2022). An RCT of virtual reality job interview training for individuals with serious mental illness in IPS supported employment. Psychiatric Services, 73(9), 1027–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Student Device Usage Report. (2022). Learning innovation. Available online: https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/5c77b4f8eced0c7b2aacbca8/625fe8c783d347008b6a9df7_LI_Student-Device-Usage-Report-April2022.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Tight, M. (2023). Employability: A core role of higher education? Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 28(4), 551–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, M. (2008). ‘The degree is not enough’: Students’ perceptions of the role of higher education credentials for graduate work and employability. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29(1), 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traphagan, T., Kucsera, J. V., & Kishi, K. (2009). Impact of class lecture webcasting on attendance and learning. Educational Technology Research and Development, 58(1), 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twyford, E., & Dean, B. A. (2024). Inviting students to talk the talk: Developing employability skills in accounting education through industry-led experiences. Accounting Education, 33(3), 296–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, S. L., & Cappelli, P. (2006). Understanding the determinants of employer use of selection methods. Personnel Psychology, 56(1), 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. (2024, June 30). It is the end of the road for two Meta Quest VR headsets. Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/andrewwilliams/2024/06/30/it-is-the-end-of-the-road-for-two-meta-quest-vr-headsets/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Witmer, B. G., & Singer, M. J. (1998). Measuring presence in virtual environments: A presence questionnaire. Presence, 7(3), 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zając-Lamparska, L., Wiłkość-Dębczyńska, M., Wojciechowski, A., Podhorecka, M., Polak-Szabela, A., Warchoł, Ł., Kędziora-Kornatowska, M., Araszkiewicz, A., & Izdebski, P. (2019). Effects of virtual reality-based cognitive training in older adults living without and with mild dementia: A pretest–posttest design pilot study. BMC Research Notes, 12, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zechner, O., Kleygrewe, L., Jaspaert, E., Schrom-Feiertag, H., Hutter, R. I. V., & Tscheligi, M. (2023). Enhancing operational police training in high stress situations with virtual reality: Experiences, tools and guidelines. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction, 7(2), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Screenshot of Bodyswaps Employability Simulation.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of Bodyswaps Employability Simulation.

Figure 2.

Factor loadings for items in the student sample employability skills questionnaire. Note. ES denotes Employability Skills items, with the number indicating the question (e.g., ES_2 = item 2).

Figure 2.

Factor loadings for items in the student sample employability skills questionnaire. Note. ES denotes Employability Skills items, with the number indicating the question (e.g., ES_2 = item 2).

Figure 3.

Factor loadings for UEQ-S pragmatic items in the student questionnaire. Note. UEQSP denotes UEQ-S pragmatic items, with the number indicating the question (UEQSP_2 = item 2).

Figure 3.

Factor loadings for UEQ-S pragmatic items in the student questionnaire. Note. UEQSP denotes UEQ-S pragmatic items, with the number indicating the question (UEQSP_2 = item 2).

Figure 4.

Factor loadings for UEQ-S hedonic items in the student sample questionnaire. Note. UEQSH denotes UEQ-S Hedonic items, with the number indicating the question number (e.g., UEQSH_1 = item 1).

Figure 4.

Factor loadings for UEQ-S hedonic items in the student sample questionnaire. Note. UEQSH denotes UEQ-S Hedonic items, with the number indicating the question number (e.g., UEQSH_1 = item 1).

Figure 5.

Factor loadings for the immersive presence items in the student sample questionnaire. Note. P denotes Presence items, with the number indicating the question (i.e., P_1 = item 1).

Figure 5.

Factor loadings for the immersive presence items in the student sample questionnaire. Note. P denotes Presence items, with the number indicating the question (i.e., P_1 = item 1).

Figure 6.

Factor loadings for items in the staff sample employability skills questionnaire. Note. ES denotes Employability Skills items, with the number indicating the question (e.g., ES_2 = item 2).

Figure 6.

Factor loadings for items in the staff sample employability skills questionnaire. Note. ES denotes Employability Skills items, with the number indicating the question (e.g., ES_2 = item 2).

Figure 7.

Factor loadings for UEQ-S pragmatic items in the staff sample questionnaire. Note. UEQSP denotes UEQ-S pragmatic items, with the number indicating the question (UEQSP_3 = item 3).

Figure 7.

Factor loadings for UEQ-S pragmatic items in the staff sample questionnaire. Note. UEQSP denotes UEQ-S pragmatic items, with the number indicating the question (UEQSP_3 = item 3).

Figure 8.

Factor loadings for UEQ-S hedonic items in the staff sample questionnaire. Note. UEQSH denotes Hedonic items, with the number indicating the question (e.g., UEQSH_4 = item 4).

Figure 8.

Factor loadings for UEQ-S hedonic items in the staff sample questionnaire. Note. UEQSH denotes Hedonic items, with the number indicating the question (e.g., UEQSH_4 = item 4).

Figure 9.

Factor loadings for immersive presence items in the staff sample questionnaire. Note. P denotes Presence items, with the number indicating the question (e.g., P_2 = item 2).

Figure 9.

Factor loadings for immersive presence items in the staff sample questionnaire. Note. P denotes Presence items, with the number indicating the question (e.g., P_2 = item 2).

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Employability Skills, UEQ-S Pragmatic, UEQ-S Hedonic and Immersive Presence Questionnaires.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Employability Skills, UEQ-S Pragmatic, UEQ-S Hedonic and Immersive Presence Questionnaires.

| | Employability Skills | UEQ-S

Pragmatic | UEQ-S

Hedonic | Immersive

Presence |

|---|

| | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

|---|

| VR | 18.94 | 5.36 | 0.68 | 0.62 | 0.31 | 0.74 | 30.00 | 5.85 |

| Desktop | 19.78 | 4.06 | 0.75 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.56 | 29.22 | 7.16 |

| Lecture | 20.33 | 4.42 | 0.50 | 1.22 | 0.05 | 0.89 | 32.50 | 10.17 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |