Preservice Secondary School Teachers’ Knowledge and Competencies When Reflecting on the Incorporation of Gamification in the Teaching of Mathematics

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To what extent does a gamified training cycle contribute to preservice mathematics teachers’ ability to incorporate gamification into their didactic proposals?

- Which arguments do preservice teachers give when justifying the use of gamification and what does this reveal about the development of their reflective competencies based on the Didactical Suitability Criteria?

- How do preservice teachers’ arguments about gamification evolve between the initial reflection after the training cycle and the subsequent redesign documented in their Master’s Final Projects?

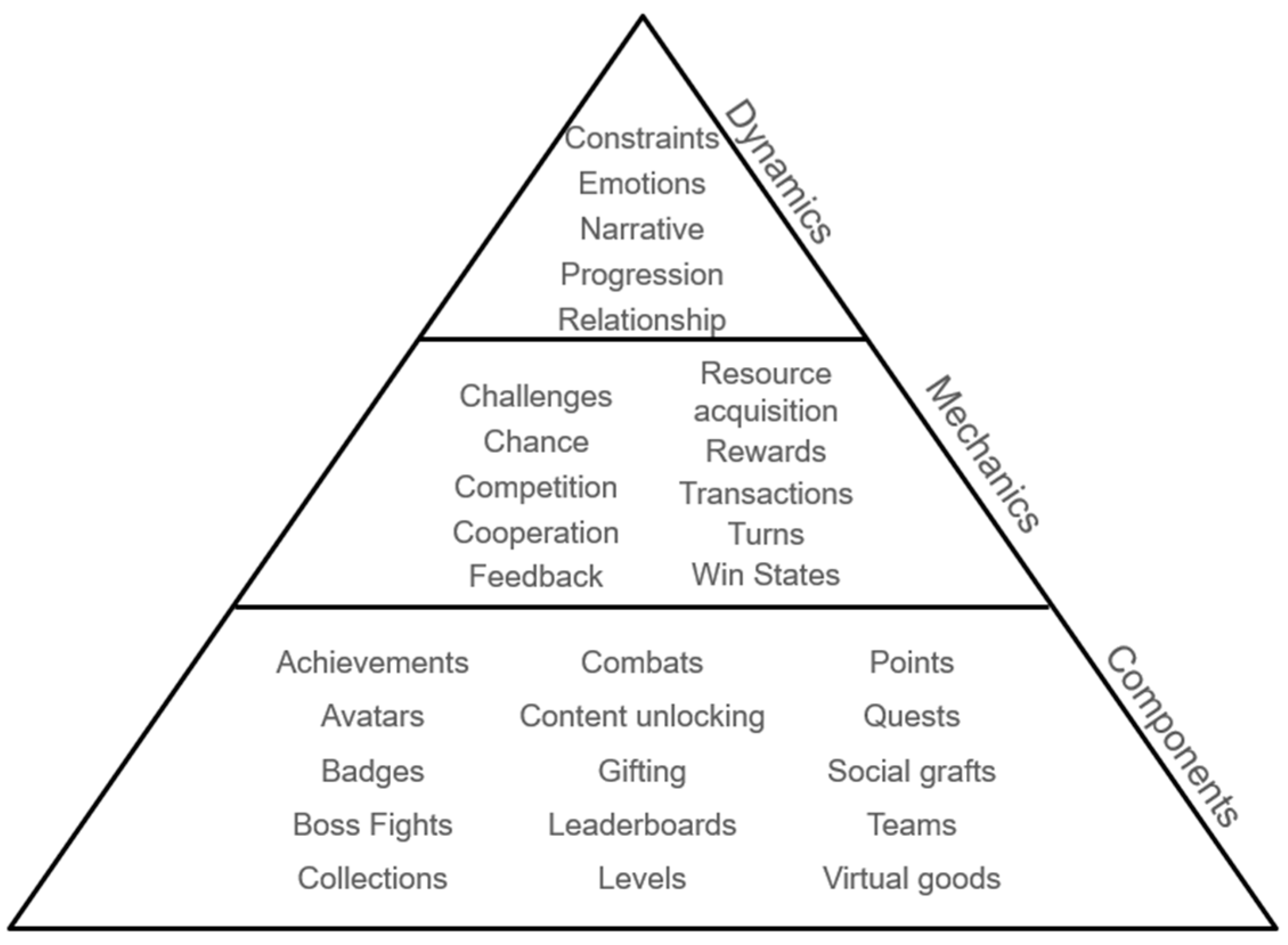

1.1. Gamification

1.2. Model of Didactic–Mathematical Knowledge and Competencies

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study’s Approach

2.2. Teachers’ Reflection in the Master’s Programme Focusing on the Gamified Training Cycle

- (a)

- Case analysis (without theory): Students are asked to read and analyse classroom episodes, making an assessment based on their prior knowledge without being provided with any guidelines.

- (b)

- Emergence of different types of didactical analysis (descriptive, explanatory, and evaluative): The sharing of analyses conducted by the different groups allows for observations of how the whole group considers these three types of didactical analysis, even though each group only addresses some of them.

- (c)

- Trends in mathematics teaching: The analysed episodes were selected so that participants implicitly apply some of the current trends in mathematics teaching (Breda et al., 2018). Then, participants are shown any of the trends that were used implicitly.

- (d)

- Theory (suitability criteria): The next step is to comment that, in mathematics didactics, different authors have made attempts to compile criteria to guide teachers’ practice so that it is of high quality (Charalambous & Praetorius, 2018; Hill et al., 2008; Prediger et al., 2022), and to note that one of these compilations is the DSC construct. It is explained that the DSC should be understood as principles emanating from the argumentative discourse of the educational community, oriented towards achieving consensus on what can be considered best practice. It is also explained that, for the development of the didactic suitability construct, current trends in mathematics teaching have been considered (NCTM, 2000), as well as principles and the contributions of different theoretical approaches in the area of mathematics didactics (Breda et al., 2018; Godino et al., 2013).

- (e)

- Read and comment on parts of some MFPs from previous courses in which the PTs used the DSC to assess the didactic sequence they implemented.

- (f)

- In the Internship and Master’s Final Project subjects, students use the DSC to assess their own practice, specifically the sequence they have designed and implemented. They are required to conduct a redesign and improve the aspects indicated in the assessment that can and should be enhanced.

2.3. Data Source

2.4. Data Analysis Process

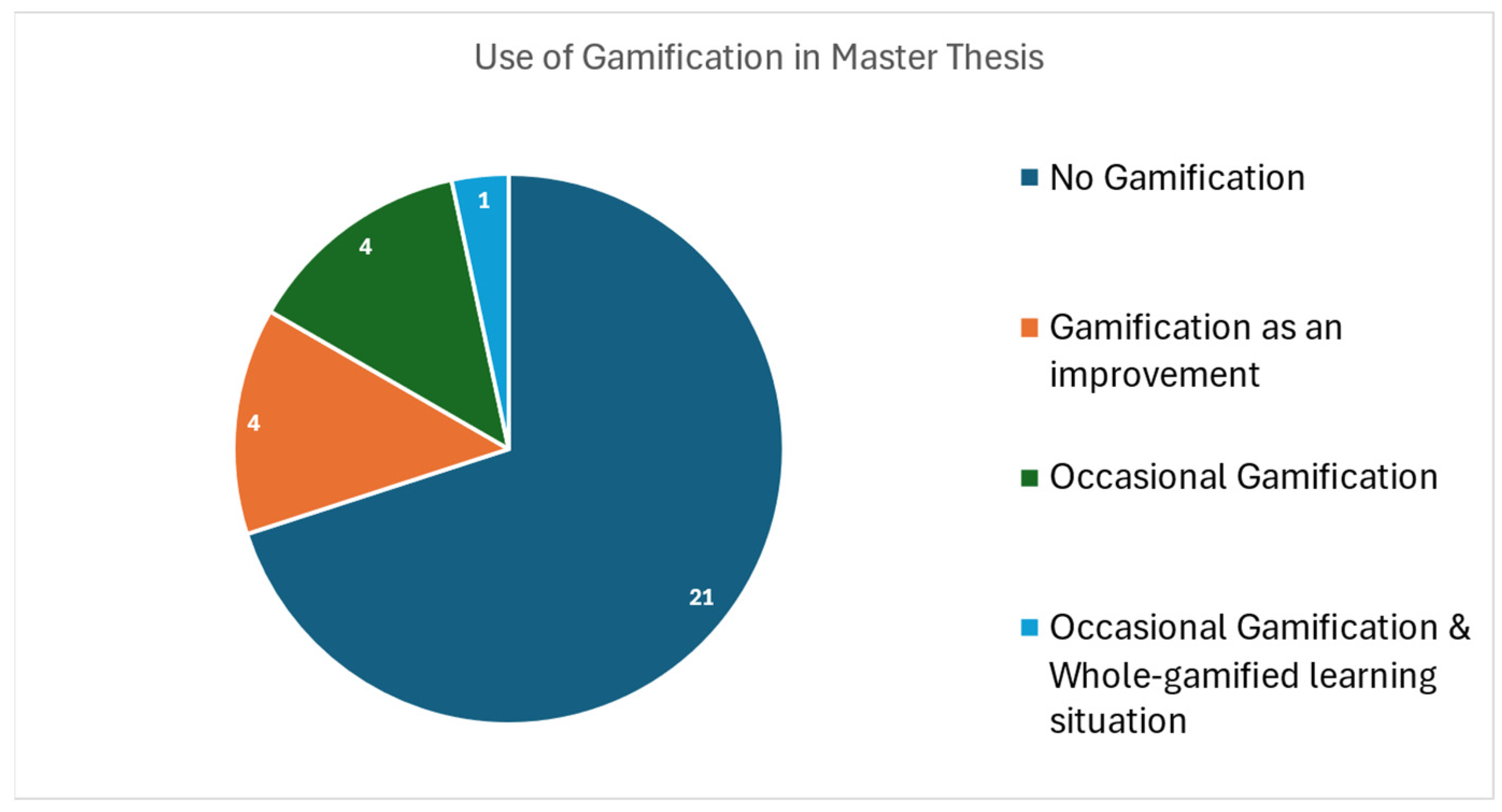

2.4.1. Phase 1: Classification of MFPs According to Gamification Use

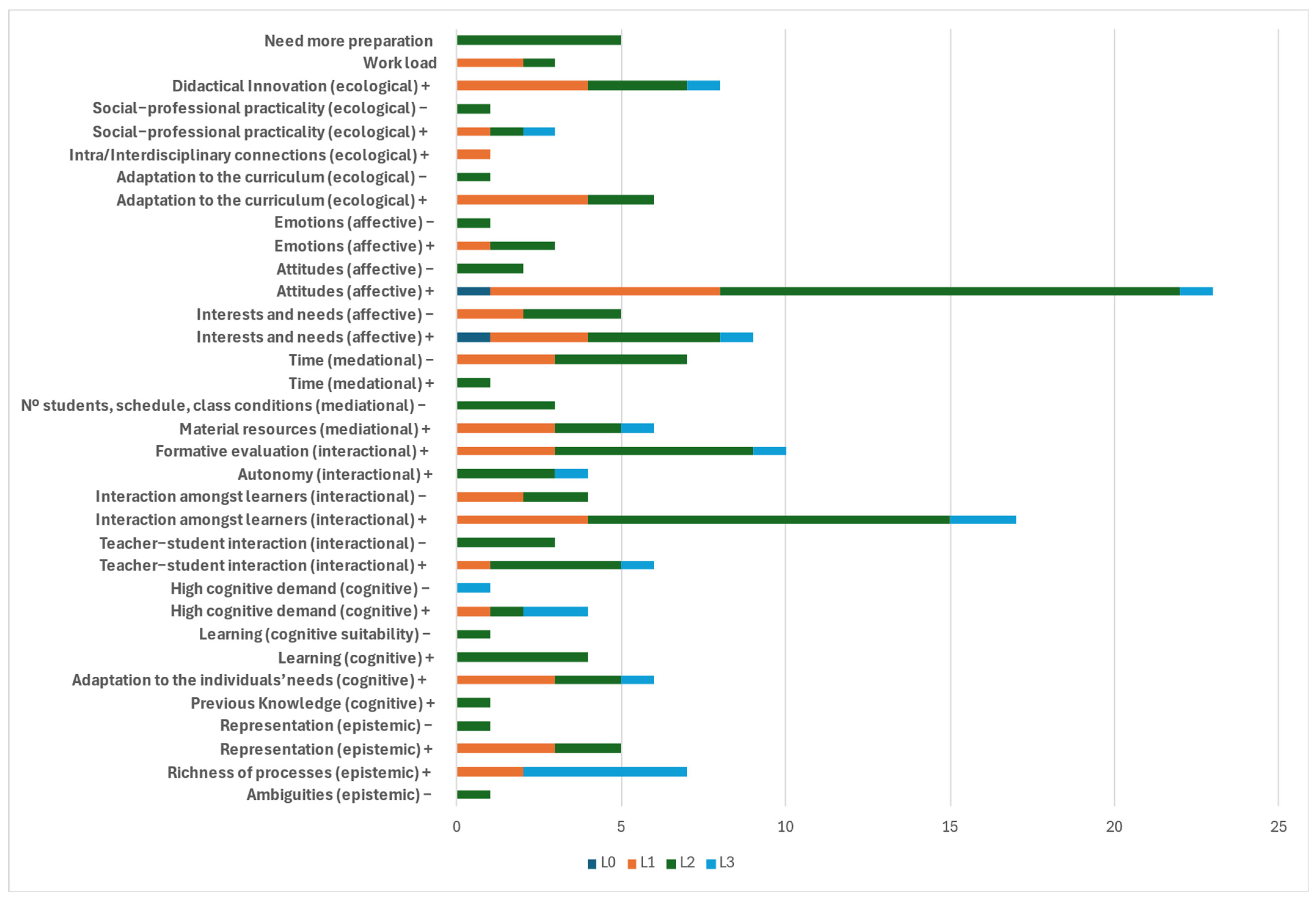

2.4.2. Phase 2: Coding of Justifications Using DSC

2.4.3. Phase 3: Assessment of Reflective Competency Levels

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Use of Gamification in Master’s Final Projects

3.2. Analysis of Reflections Based on the DSC and the Level of the Subcompetency of Analysis and Evaluation of Didactical Suitability

“[…] regarding epistemic suitability, it is improved the section of Richness of Processes. It is replaced the traditional method where it was prioritised mechanisation and memorisation by role-playing with challenges that encourage students to explore, discuss and translate into mathematical language, use different types of representation to better understand what is happening, and communicate with team members and other teams.”(Alberca, 2025, p. 13)

“[…] the activity is designed to deepen the Derby Game project (…) So now we ask them to open the app and click on the ‘How is it made?’ or ‘See Inside’ button, and from there they can see how the game works. They need to read the code and write down on their notebook anything they understand from what is written and something they don’t. It’s normal not to understand everything, but they should find a line they do understand, what it means or what it’s for. This will allow them to make a first approach to programming using Scratch and start familiarising themselves with the code used to create the app. The final goal will be for them to make any improvement to the game.”(Bergadà, 2025, p. 31)

“PT2: Which aspects of classroom management would you change if you were to implement gamified activities in secondary education?

PT1: More time. Time. Time. We were rushing through everything, to be honest.

PT3: And the time… maybe it’s what you’re saying, but I’d prefer that instead of doing six activities in half an hour, we did two and then had some time to digest, to explain. ‘Let’s explain, guys, let’s discuss: why didn’t it work for you? Why did it? Why didn’t we get feedback on why it did or didn’t?’

PT1: Well, I guess that it was this way…

PT3: Yes, because we’re adults. Yes, yes, yes…

PT1: We were interested in seeing as many as possible, because we have the capacity to check them later on our own.

PT3: But with students, it would be interesting to dedicate more time, wouldn’t it?”

“PT2: How would you plan and manage time if you wanted to apply gamification in your teaching practice? And what would be the most suitable classroom conditions?

PT3: Well, I really think the classroom needs to be a collaborative space, right? Because, I mean, a classroom like the one we have here is terrible for this kind of activity.

PT2: It must be a classroom…

PT4: In terms of furniture, it needs tables and chairs that…

PT2: …allow for group formation.

PT4: Exactly, that allow students to sit in circles, or if they’re desks, at least desks that can be actually rearranged. Because of course, if they’re fixed to the floor, there’s no way… then it’s not possible. Definitely, it’s not possible.

PT2: And the teacher needs to be able to move around easily, not just to help, but also to observe and assess. In the end, you can also evaluate based on what you’re seeing in classroom.”

“PT1: So, the idea was also to see whether the gamification of this subject helped us understand how this strategy can be applied to mathematics teaching. Yes, yes… but I find it quite complicated. All that stuff we did here with GeoGebra, that whole story…

PT2: It’s a lot more work.

PT1: Yes, I have to invent everything myself.

PT3: Sure, yes… no… but well, in the end you already have many resources made.

PT3: The only problem…

PT2: … is finding them.”

In turn, PTs expressed the following in the debate regarding the need for further preparation:

“PT1: How do you assess the connection between what you have learned in the course and what you could apply in schools with different educational projects, resources, and contexts? Do you feel prepared to adapt what you have learned to diverse contexts?

PT5: No.

PT4: I mean… thinking that with ten hours of lessons you become an expert in gamification… is a bit presumptuous…

PT5: Yes, I think now we have more options.

PT3: Sure, we have a basis, I think.

PT4: Exactly.”

“PT5: (…) if I think that in high schools or secondary schools where they already work with project-based learning and highly innovative pedagogies, I believe that it might be easier to apply this because students are already more used to different dynamics.”

“PT1: I also think it’s about strategies, in this case, thinking about all the resources, right? Whether it’s Scratch, GeoGebra, manipulative games… rather than responding to current needs, they respond to needs that have always existed. The difference is that now they’re being addressed. I mean, now there’s a bet on learning through experimentation, not just theory. And so, something is being done about it. Obviously not in all schools, but the focus is starting to shift towards the need for different tools to keep students engaged, connected, and motivated. How do we do that? With resources. Using things we already knew that worked, but which previously weren’t given the importance they deserved, because the traditional model placed a lot of emphasis on the teacher as the central figure, right? And students as sheep. ‘I recite and they repeat.’ And it has already been seen to be ineffective for the learning experience. So yes: we need strategies aligned with this new perspective.”

“PT3: Because I think, for example, we were complaining that the GeoGebra part would have required more time—the introduction, and whatever—. But it’s also about whether you’re willing to lose or, rather, invest time, I mean, to dedicate more time, you know? Like… I always have that doubt. I was talking about it the other day with another teacher… With the teacher (name of another teacher)… this idea of: ‘Okay, I don’t know, I know that if I do this activity, it will probably take up three lessons, for example.’

PT5: Yes.

PT3: Am I willing to…?

PT5: Of course, because you still have to cover the syllabus.

PT3: Exactly. Spending more time on one thing means having less time for something else.”

“Regarding emotional suitability, it was observed that student motivation was higher in activities with a playful or creative component. Therefore, the initial idea of the contest ‘Put on the Function Glasses’ is recovered, and a return to a more formative evaluation is proposed, including co-evaluation and self-evaluation as tools for regulating one’s own learning.”(Fernández, 2025, p. 41)

“On the other hand, the usual approach to preparing for university entrance exams in Baccalaureate (formal explanation of theory, sample exam, mechanical exercise solving in isolation…) is replaced by collective learning in which everyone must participate and be responsible with their peers. Argumentation with group members is encouraged, as well as dialogue and the presentation of ideas to other groups in the classroom.”(Alberca, 2025, p. 14)

3.3. Evolution of Justifications According to the Time at Which the Teaching Reflection Occurred

“PT4: The thing is, I don’t know to what extent, to work on all mathematics content, gamification is necessary. Yes, for some… I think for some concepts, yes, but not all. And also, not in every year group. I mean, in a baccalaureate course, maybe, I’m not sure to what extent gamification would just waste more time. In secondary education, you do need to give them a lot of prior knowledge, right? I mean, yes. With gamification, maybe you help consolidate knowledge in secondary education, but then in baccalaureate, I think it needs to be more nuanced, because maybe there you need to get more into the subject matter.”

“The fact that all chapters are modelled problems in which students choose resolution strategies and apply logic means that Competency 1 of the curriculum (Department of Education, 2022) is fully addressed. Thanks to the fact that most chapters require justification of the procedure followed, students also work on Competency 2. As with Competency 1, Competency 3 is also present in all chapters, as each one creates a path where the team gradually builds mathematical knowledge through problem posing and solving them with reasoning and creativity. Competency 4 is mainly addressed in Annex C.6 (where students are asked to change functions and observe the new trend) and Annex C.9 (where they are explicitly asked to invent modifications to fix discontinuities). As for Competency 5, it is present in all chapters: the exercises constantly require changing representations and comparing different types. Competency 6 is clearly addressed in Annex C.10, where mathematics and technology are worked on simultaneously. All chapters are carried out collectively (in groups of three), aiming to develop Competencies 7 and 9.”(Alberca, 2025, p. 15)

“PT3: I mean, if I understand the question, like whether you’ve learned things in the course that are relevant for addressing diversity. I haven’t learned anything in the course, nor in the master. I mean, no. I mean, let’s say, right? We have, I don’t know if you’ve done your internship, a class of 20 students and some have dyscalculia. Of course, how do you do a calculation or number activity with a student who has dyscalculia? You can’t give them the same exercise or the same activity.”

“PT1: What aspects of what you’ve learned in the course do you think are most relevant for addressing diversity in the classroom? Have you learned to design activities that consider different levels of knowledge?

PT3: The different levels of knowledge, yes, for example, the Halloween activity, in the end you had four tasks, some easier than others. You know, you propose different techniques.

PT2: And I suppose also, if you make groups, you’re also trying to…

PT1: Heterogenize.

PT2: Exactly. Collaborative work. Critical thinking…”

“However, during the initial observation phase of the internship, I held conversations with the group tutors and also with the school’s counsellors to identify the most relevant educational needs. In the case of students with ASD, for example, I was informed that they showed strong skills in drawing. With this information, I tried to ensure they felt recognised and involved in the project, both in the roles distribution in cooperative work and in the application activities involving graphical representation with GeoGebra. One student surprised us by spontaneously creating a personalised map of their amusement park, while another proposed designing attractions using polygonal shapes with notable precision.”(Gimeno, 2025, p. 10)

PT4: Sometimes, when I gamify a concept, I feel like I’m hiding the mathematics, you know? It’s like you’re so focused on the game, but you’re not really understanding the maths.

PT2: I was thinking the same, like maybe something more formal is missing, you know?

PT4: Because I was thinking the same thing, it’s true that you can use concepts to solve the games, but if you want those concepts to be learned effectively, they need to be formalised. I mean, you have to say, “this is this theorem.”

PT1: Yes, like we said, the complement, the institutionalisation.

“The Design Project has a dual focus: oral communication to present the design to peers and teachers, and written communication in the final report.

The space for manipulation and experimentation was mainly reserved for the project work. Models studied in lectures were applied, and knowledge was later explored through the design and layout of the park. (…)

All the activities, including the competency-based tasks, involve argumentation, as does the Project. However, the level and depth of argumentation vary depending on the activity, with the Park Project offering greater depth due to the reflective level and the nature of the questions to be justified in the final report: purpose of the park, use of space, socio-cultural utility of the space, etc.”(Jdayah, 2025, pp. 8–9)

“PT2: There’s something that happens to me, because, for example, today’s activity (Kafka’s Metamorphosis) seemed perfect to me, as it was quite fun… But there wasn’t too much context. Because one thing I notice is that, for example, in the GeoGebra one, there was so much information, you know? To create the game, the game’s context… Then there was loads of information, and in the end, what you had to do was actually a small part. But you had to read a lot. That distracted me, maybe because I get… Yes, I get distracted easily. But I think of people who struggle…

PT5: Yes, yes, yes…

PT2: Because it kind of takes your focus away, a bit, because you have to create the characters. There was a story, and then what it asked you to do seemed much simpler than the story.

PT4: I agree. It’s like: ‘What’s the actual question? What are you asking me?’ And it was so hidden… and it’s like ‘I’m not getting it’.”

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MFP | Master’s Final Projects |

| PT | Preservice teachers |

| TC | Training cycle |

| DSC | Didactical Suitability Criteria |

Appendix A

| Sessions | Activities | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Session 1: Introduction to the module and blocks (2 h). | Lisa Simpson: The Electoral Adventure toward the Student Council:

| Subject presentation, introduction to the subject methodology, and three acts presenting activities. |

| Session 2: Materials for Numerical Sense and Algebra Workshop (2 h) | Initial quest: “The Trail of Galactic Functions”. (Points for the leaderboard).

| Initial activity from a GeoGebra applet. 10 min materials workshop for experimentation and problem-solving. Activities were carried out in teams of 5–6 people. Materials:

|

| Session 3: Scratch Workshop (2 h) | Scratch Workshop with Jack Skellington

| This is an initial use of Scratch for concrete math activities. The activities are performed in pairs and experimentation is encouraged in the programme to learn how to use the software. |

| Session 4: Geogebra Workshop (4 h) | GeoGebra Workshop: Avatar—The Return to Pandora:

| The programme is presented using examples of activities where the PT is the one who builds the applet. It is a set of activities where they work with the different views that the program offers. |

| Session 5: Geometry Materials Workshop (4 h) | Quest: The Wandering Knight’s potion: Geometry materials workshop by corners with Don Quixote:

| The first activity is an experiment to demonstrate the volumes of different geometric figures. The workshop by corners shows six activities, adapted from (CESIRE—CREAMAT, n.d.), of 15 min each to experiment with manipulative materials while solving different problems. Material:

|

| Session 6: Statistic activities, BreakOut y blocks closure (4 h) | Probability and statistics activities adapted from (ADEMGI, n.d.; Grup Cúbic, 2017; Institut El Joncar, n.d.):

Final debate of the subject’s methodology. | Session begins with various probability and statistical activities to encourage experimentation. BreakOut is a digital activity at Genially. This activity is made up of various problems; the resolution of some of them requires the use of different manipulative materials. Material:

|

References

- ADEMGI. (n.d.). Tema 13: Estadística i probabilitat. Associació d’Ensenyants de Matemàtiques de les Comarques Gironine. Available online: https://ademgi.feemcat.org/materials/tema13/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Alberca, N. (2025). Límits i continuïtat a Primer de Batxillerat: Proposta de millora [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Araya, R., Ortiz, E. A., Bottan, N., & Cristia, J. (2019). ¿Funciona la gamificación en la educación? Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubanell i Pou, A. (2015). Orientacions pràctiques per a la millora de la geometria. Quaderns d’Avaluació, 31(31), 63–137. [Google Scholar]

- Balaskas, S., Zotos, C., Koutroumani, M., & Rigou, M. (2023). Effectiveness of GBL in the engagement, motivation, and satisfaction of 6th grade pupils: A Kahoot! approach. Education Sciences, 13(12), 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergadà, R. (2025). Proposta de millora d’una intervenció didàctica sobre figures planes a 2n d’ESO [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Bishop, A. J. (1999). Enculturación matemática: La educación matemática desde una perspectiva cultural. Grupo Planeta (GBS). [Google Scholar]

- Bonavia, S. (2025). Introduir les funcions a 3r d’ESO: Proposta de millora de la seqüència de tasques realitzades durant el Pràcticum a l’Escola Joan Pelegrí [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Breda, A., Font, V., & Pino-Fan, L. R. (2018). Criterios valorativos y normativos en la Didáctica de las Matemáticas: El caso del constructo idoneidad didáctica. Bolema: Boletim de Educação Matemática, 32(60), 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breda, A., Pino-Fan, L. R., & Font, V. (2017). Meta didactic-mathematical knowledge of teachers: Criteria for the reflection and assessment on teaching practice. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 13(6), 1893–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, M., Castillo, M. J., Beltrán-Pellicer, P., Giacomone, B., & Godino, J. D. (2020). Análisis didáctico de una lección sobre proporcionalidad en un libro de texto de primaria con herramientas del enfoque ontosemiótico. Bolema: Boletim de Educação Matemática, 34(66), 40–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, M., & Godino, J. D. (2022). Assessing the epistemic analysis competency of prospective primary school teachers on proportionality tasks. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 20(2), 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CESIRE—CREAMAT. (n.d.). Laboratori de matemàtiques. Available online: https://sites.google.com/xtec.cat/cesire-matematiques-campanyes/laboratori-de-matem%C3%A0tiques (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- CESIRE—CREAMAT. (2014, October 27). Quants cubs formen la torre? ARC—Aplicació de Recursos al Currículum. Available online: https://apliense.xtec.cat/arc/node/30184 (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Charalambous, C. Y., & Praetorius, A.-K. (2018). Studying mathematics instruction through different lenses: Setting the ground for understanding instructional quality more comprehensively. ZDM, 50(3), 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornellà, P., Estebanell, M., & Brusi, D. (2020). Gamificación y aprendizaje basado en juegos. Enseñanza de las Ciencias de la Tierra, 18(1), 5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, A., Breda, A., & Sánchez, A. (2024a). Gamificación en la enseñanza secundaria de matemáticas: Análisis de secuencias didácticas en trabajos de fin de máster de futuros docentes. In F. M. Sirignano, R. Martínez-Roig, & A. López Padrón (Eds.), Enseñanza y aprendizaje en la era digital desde la investigación y la innovación (pp. 65–75). Editorial Octaedro. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, A., Breda, A., Sánchez, A., Farsani, D., & Tinti, D. S. (2024b). The incorporation of the active gamification methodology in the didactic units of Preservice Secondary mathematics teachers. Caminhos da Educação Matemática em Revista (Online), 14(3), 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, A., Breda, A., Sánchez, A., & Font, V. (2026). Didactic suitability criteria to organise mathematics teachers’ reflection aimed at improving instructional processes in mathematics: The case of gamification and game-based learning. In C. Fernández, S. Llinares, & B. H. Choy (Eds.), Innovations in initial mathematics teacher education. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cortés, A., Breda, A., Sánchez, A., Font, V., & Sala-Sebastià, G. (2025). Metodologías lúdicas y su idoneidad en la enseñanza del álgebra en secundaria: Un análisis de trabajos de fin de máster. In M. Burgos, M. C. Cañadas, J. M. Marbán, & I. Polo-Blanco (Eds.), Investigación en Educación Matemática XXVIII (pp. 148–155). SEIEM. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado Palacios, M. L., Ángel Reyes, C. E., Saltos Palacios, G. I., & Del Castillo Espinal, J. R. (2022). La gamificación en la educación: Una estrategia didáctica, en el colegio Dr. Luis Celleri Avilés. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 6(4), 3116–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellos, R. (2015). Kahoot! A digital game resource for learning. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 12(4), 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Education. (2022). Decret 171/2022, de 20 de setembre, d’ordenació dels ensenyaments de batxillerat (DOGC nº 8758). Diari Oficial de la Generalitat de Catalunya. Available online: https://portaljuridic.gencat.cat/eli/es-ct/d/2022/09/20/171 (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011, September 28–30). From game design elements to “gamefulness”: Defining gamification. 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments (pp. 9–15), Tampere, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- Deulofeu, J. (2010). Prisioneros con dilemas y estrategias dominantes. RBA. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C. Y., Zakaria, M. I., & Muslim, N. E. I. (2023). A systematic review: Challenges in implementing problem-based learning in mathematics education. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 12(3), 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, S. (2025). Proposta de millores de la intervenció didàctica de funcions lineal i quadràtica (3er ESO) [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Font, V. (1994). Motivación y dificultades de aprendizaje en matemáticas. Suma, 17(1), 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Font, V. (2024). Teaching innovation and introduction to educational research in mathematics education. Available online: https://guies.uab.cat/guies_docents/public/portal/html/2024/assignatura/45454/en (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Font, V., Breda, A., Sala-Sebastià, G., & Pino-Fan, L. R. (2024). Future teachers’ reflections on mathematical errors made in their teaching practice. ZDM—Mathematics Education, 56(6), 1169–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Font, V., Planas, N., & Godino, J. D. (2010). Modelo para el análisis didáctico en educación matemática. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 33(1), 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Segovia, Á. M. (2023). Importancia de la gamificación en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Polo del Conocimiento, 8(8), 844–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Caballero, C. (2017, September 26). Capsa Masu. ARC—Aplicació de Recursos al Currículum. Available online: https://apliense.xtec.cat/arc/node/30732 (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- García Collantes, D. E. (2020). Gamificación y competencias matemáticas en los estudiantes de 6to grado de la I. E. 2071 César Vallejo, Los Olivos 2019 [Master’s thesis, Universidad César Vallejo, Repositorio Digital Institucional Universidad César Vallejo]. Available online: https://repositorio.ucv.edu.pe/handle/20.500.12692/41937 (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Gimeno, S. (2025). Què podem dissenyar amb la geometria? [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Godino, J. D., Batanero, C., Rivas, H., & Arteaga, P. (2013). Componentes e indicadores de idoneidad de programas de formación de profesores en didáctica de las matemáticasSuitability components and indicators of teachers’ education programs in mathematics education. Revemat: Revista Eletrônica de Educação Matemática, 8(1), 46–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodal, T. (2000). Video games and the pleasures of control. In D. Zillmann, & P. Vorderer (Eds.), Media entertainment: The psychology of its appeal (pp. 197–213). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Grup Cúbic. (Director). (2017, November 4). Role play—Passeig aleatòri [Video recording]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eK7jtb2zlL4 (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Hassan, L., & Hamari, J. (2020). Gameful civic engagement: A review of the literature on gamification of e-participation. Government Information Quarterly, 37(3), 101461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, H. C., Blunk, M. L., Charalambous, C. Y., Lewis, J. M., Phelps, G. C., Sleep, L., & Ball, D. L. (2008). Mathematical knowledge for teaching and the mathematical quality of instruction: An exploratory study. Cognition and Instruction, 26(4), 430–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguin García, F. Y., Holguin Rangel, E. G., & Garcia Mera, N. A. (2020). Gamificación en la enseñanza de las matemáticas: Una revisión sistemática. Telos, 22(1), 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut El Joncar. (n.d.). La caixa de varga. Available online: https://lacaixadevarga.eljoncar.cat/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Jdayah, F. (2025). Proposta de millora d’una Situació d’Aprenentatge sobre l’estudi de la Geometria al pla a un curs de 3r d’ESO [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Jiménez, C., Arís, N., Ruiz, Á. A. M., & Orcos, L. (2020). Digital escape room, using Genial.Ly and a breakout to learn algebra at secondary education level in Spain. Education Sciences, 10(10), 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Hernández, D., González Ortiz, J. J., & Tornel Abellán, M. (2020). Metodologías activas en la universidad y su relación con los enfoques de enseñanza. Profesorado, Revista De Currículum Y Formación Del Profesorado, 24(1), 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E., Weber, K., Fukawa-Connelly, T. P., Mahmoudian, H., & Carbone, L. (2025). Collaborating with mathematicians to use active learning in university mathematics courses: The importance of attending to mathematicians’ obligations. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 119(1), 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, G. G. V., Moosa, H., Smith, J., & Davidson, F. E. (2025). Learning through play: Educators and students reflect on a gamified assessment. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, 57(1), 102139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapeña, A. (2025). Millora de la situació d’aprenentatge de trigonometria quart de la eso [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Ledezma, C., Breda, A., & Font, V. (2024). Prospective teachers’ reflections on the inclusion of mathematical modelling during the transition period between the face-to-face and virtual teaching contexts. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 22(5), 1057–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llargués, J. A. (2025). Proposta de millora d’una situació d’aprenentatge d’equacions lineals. Autonomous University of Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- López, P., Rodrigues-Silva, J., & Alsina, Á. (2021). Brazilian and Spanish mathematics teachers’ predispositions towards gamification in STEAM education. Education Sciences, 11(10), 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvasi, V., & Recio Moreno, D. (2022). Percepción de las estrategias de gamificación en las escuelas secundarias italianas. Alteridad, 17(1), 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, D. (2016a, March 1). [3ACTS] Nissan girl scout cookies. dy/dan. Available online: https://blog.mrmeyer.com/2016/3acts-nissan-girl-scout-cookies/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Meyer, D. (Director). (2016b, March 1). Nissan girl scout cookies—Act one [Video recording]. Available online: https://vimeo.com/157324585?fl=pl&fe=sh (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Mula-Falcón, J., Moya-Roselló, I., & Ruiz-Ariza, A. (2022). The active methodology of gamification to improve motivation and academic performance in educational context: A meta-analysis. Review of European Studies, 14(2), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseri, R. N. N., Abdullah, R. N. R., & Esa, M. M. (2023). The effect of gamification on students’ learning. International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development, 12(1), 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCTM. (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. [Google Scholar]

- Numberphile. (Director). (2018, August 31). The dollar game [Video recording]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U33dsEcKgeQ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Ortiz-Mendoza, G. J., & Guevara-Vizcaíno, C. F. (2021). Gamificación en la enseñanza de Matemáticas. Episteme Koinonia, 4(8), 164–184. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Panata, Y., Burbano-Santamaria, S., Hernández-Domínguez, P., Andrade-Varela, J., Ortiz-Panata, Y., Burbano-Santamaria, S., Hernández-Domínguez, P., & Andrade-Varela, J. (2025). Use of gamification for the inclusion of students with SEN. In AI and computing in industrial education handbook (pp. 3–20). Lecture notes in networks and systems book series. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picart, O. (2025). Unitat didàctica de fraccions al primer curs de l’ESO [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Pino-Fan, L. R., Assis, A., & Castro, W. F. (2015). Towards a methodology for the characterization of teachers’ didactic-mathematical knowledge. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 11(6), 1429–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Fan, L. R., Castro, W. F., & Font, V. (2023). A macro tool to characterize and develop key competencies for the mathematics teacher’ practice. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 21(5), 1407–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñero, J. C. (2020). Educational escape rooms as a tool for horizontal mathematization: Learning process evidence. Education Sciences, 10(9), 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prediger, S., Götze, D., Holzäpfel, L., Rösken-Winter, B., & Selter, C. (2022). Five principles for high-quality mathematics teaching: Combining normative, epistemological, empirical, and pragmatic perspectives for specifying the content of professional development. Frontiers in Education, 7, 969212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig Adam, P. (1956). Didáctica matemática eurística. Instituto de Formación del Profesorado de Enseñanza Laboral. [Google Scholar]

- Pujolà, J.-T. (2024). La gamificación: Una estrategia didáctica en el ámbito educativo. In O. Ripoll, & J.-T. Pujolà (Eds.), La gamificación en la educación superior: Teoría, práctica y experiencias didácticas (pp. 17–26). Ediciones Octaedro. [Google Scholar]

- PuntMat. (2018, December 31). Nombres irracionals i materials manipulatius. PuntMat. Available online: https://puntmat.blogspot.com/2018/12/nombres-irracionals-i-materials.html (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Reyssier, S., Hallifax, S., Serna, A., Marty, J., Simonian, S., & Lavoue, E. (2022). The impact of game elements on learner motivation: Influence of initial motivation and player profile. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 15(1), 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripoll, O. (2014). Gamificar vol dir fer jugar. CCCB LAB. Available online: https://lab.cccb.org/ca/gamificar-vol-dir-fer-jugar/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Rodríguez, D. (2025). Teorema de Pitàgores: Propostes de millora en la seva implementació [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Sánchez, A. (2021, January 22). BreakoutM. Genially. Available online: https://view.genially.com/600a9a043594d40d02263ca6/interactive-content-breakoutm (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Sánchez, A., & Burgués, P. (2020). Scratch com a eina matemàtica creativa. In Actes del Congrés Català d’Educació Matemàtica (C2EM). Federació d’Entitats per a l’Ensenyament de les Matemàtiques a Catalunya, Tarragona-Reus. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, A., Font, V., & Breda, A. (2022). Significance of creativity and its development in mathematics classes for preservice teachers who are not trained to develop students’ creativity. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 34(4), 863–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, R. (2025). Anàlisi i millora d’una unitat didàctica sobre els teoremes de Pitàgores i Tales a segon d’ESO [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Seckel, M. J., Breda, A., Font, V., & Vásquez, C. (2021). Primary school teachers’ conceptions about the use of robotics in mathematics. Mathematics, 9(24), 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seckel, M. J., Vásquez, C., Samuel, M., & Breda, A. (2022). Errors of programming and ownership of the robot concept made by trainee kindergarten teachers during an induction training. Education and Information Technologies, 27(3), 2955–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Standeven, T. (2025). Anàlisi i proposta de millora d’una intervenció didàctica a 1r de batxillerat nocturn ensenyant trigonometria [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Autonomous University of Barcelona.

- Swacha, J. (2021). State of research on gamification in education: A bibliometric survey. Education Sciences, 11(2), 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takele, M. (2020). Practices and challenges of active learning methods in mathematics classes of upper primary schools. Journal of Education and Practice, 11(13), 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Toukoumidis, A. L., & Romero-Rodríguez, L. M. (2019). Gamificación, Simulación, Juegos Serios y Aprendizaje Basado en Juegos. In Juegos y Sociedad: Desde la Interacción a la Inmersión para el cambio social (pp. 113–120). Mcgraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, I., & Barbosa, A. (2023). Active learning strategies for an effective mathematics teaching and learning. European Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 11(3), 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werbach, K., & Hunter, D. (2015). The gamification toolkit: Dynamics, mechanics, and components for the win. University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

| Criteria | Conceptualization | Components |

|---|---|---|

| Epistemic | Assesses whether the mathematics lessons are of good quality. |

|

| Cognitive | Assesses, before starting the teaching and learning process, whether the topic to be taught aligns with what the students already know, and, after this process, whether the learning achieved approximates the intended outcomes. |

|

| Interactional | Assesses whether the interaction addresses the students’ doubts or difficulties. |

|

| Mediational | Assesses the adequacy of the material and temporal resources used in the teaching and learning process. |

|

| Affective | Assesses the student’s involvement (interests and motivation) during the teaching and learning process. |

|

| Ecological | Assesses the adaptation of instructional process to the school educational project, the curricular guidelines, and the conditions of the social and professional environment, etc. |

|

| Title Preservice Teacher’s Name | Limits and Continuity in the First Year of Baccalaureate: Proposal for Improvement Alberca (2025) |

|---|---|

| Level | 1st level of Baccalaureate (16–17 years old) |

| Branch of mathematics | Functions |

| Category of the game use approach | (2) Proposes gamified activities as a potential improvement in practical intervention. |

| Which games have been used or alluded to? | Roleplay |

| Does it use the term gamification? | No |

| Extract | (Alberca, 2025, p. 14) Finally, it was tried to make the content as attractive as possible for students through drama and the resolution of simple cooperative tasks. Setting organized goals makes it difficult for students to get lost and the dialogues where the theory is explained in a more fun way make the student see learning as a game and not as exercises that they cannot solve. |

| Which component of the DSC is being referenced? | Richness of processes (epistemic suitability)+ |

| Level of development | L2 |

| Condition Number | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1 | It does not use gamification, nor does it propose the methodology as a potential improvement for practical intervention. |

| 2 | It proposes gamified activities as a potential improvement in practical intervention. |

| 3 | It occasionally uses gamification activities in practical intervention. |

| 4 | The entire intervention is based on gamification activities. |

| Ln | Description | Type of Analysis | Depth of Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| L0 | There is no analysis or justification for the use of gamification. | The analysis is superficial and ambiguous, it does not describe, explain, or evaluate the instructional process or class period. | Superficial narrative (written or discursive). The narrative does not explain what happened during the class period. |

| L1 | Superficial justification, focused on motivation or aesthetics. | Descriptive Describe what happened during the class period or study process. | Narrative that captures the essential elements of the class period analyzed. Anyone who reads or listens to the narration has an idea of what happened in the episode. |

| L2 | Partial justification, with implicit or generic references to DSC. | Explanatory Try to answer: why what happened during the class period happened (related to a phenomenon, conflict, error, etc.). | A complete and understandable narrative, which involves a detailed analysis, attempting to follow a model (e.g., if a description of mathematical activity is made, components of the ontosemiotic configuration are used to identify some primary practices, objects, and processes; used explicitly or implicitly). |

| L3 | Thorough justification, structured by the DSC components and/or the Didactic-Mathematical Knowledge and Competencies model. | Evaluative It includes elements from the previous two levels and answers the question: what can or should be improved during the class period and why? | Expert analysis of the narrative according to the systematic use of a model (e.g., a detailed description of the mathematical activity is made, the practices, primary objects, and processes, meanings of the notions used, are exhaustively identified; systems of norms that conditioned the interactions and learnings in the episode; or the eligibility criteria explicitly). |

| Type of Use of the Term Gamification | MFP (Authors) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Imprecise/confused use (misuse) | (Bonavia, 2025, pp. 9, 15, 16, 18; Lapeña, 2025, p. 15; Llargués, 2025, pp. 40, 70; Picart, 2025, p. 32; R. Sánchez, 2025, p. 21) | Direct equivalence between gamification and complete games like Kahoot! |

| Proper/substantiated use | (Gimeno, 2025, pp. 16, 22; Jdayah, 2025, pp. 13, 21, 36; Rodríguez, 2025, pp. 29, 31, 37, 42, 44, 45, 49; R. Sánchez, 2025, p. 16) | Activities with game elements and pedagogical objectives |

| Generic use without development | (Lapeña, 2025, p. 16; Llargués, 2025, pp. 16, 25; Picart, 2025, p. 40) | Mentioned as a synonym for innovation or motivation, without specification |

| Theoretical definition use | (Rodríguez, 2025, p. 16) | The only case with an explicit bibliographic definition (Kapp, 2012) |

| L0 | L1 | L2 | L3 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Debate | 0 | 29 | 60 | 0 | 89 |

| MFP | 2 | 21 | 32 | 19 | 74 |

| Total | 2 | 50 | 92 | 19 | 163 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cortés, A.; Breda, A.; Sánchez, A.; Verón, M.A. Preservice Secondary School Teachers’ Knowledge and Competencies When Reflecting on the Incorporation of Gamification in the Teaching of Mathematics. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010020

Cortés A, Breda A, Sánchez A, Verón MA. Preservice Secondary School Teachers’ Knowledge and Competencies When Reflecting on the Incorporation of Gamification in the Teaching of Mathematics. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010020

Chicago/Turabian StyleCortés, Alexandre, Adriana Breda, Alicia Sánchez, and Manuel Alejandro Verón. 2026. "Preservice Secondary School Teachers’ Knowledge and Competencies When Reflecting on the Incorporation of Gamification in the Teaching of Mathematics" Education Sciences 16, no. 1: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010020

APA StyleCortés, A., Breda, A., Sánchez, A., & Verón, M. A. (2026). Preservice Secondary School Teachers’ Knowledge and Competencies When Reflecting on the Incorporation of Gamification in the Teaching of Mathematics. Education Sciences, 16(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010020