Research Skills and Academic Literacy in Multilingual Higher Education: The Case of Kazakhstan

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Questions and Hypotheses

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

3.1. Design

- Language of study (Kazakh, Russian, or English as the medium of instruction);

- Self-reported language use in academic tasks (reading, writing, searching for sources);

- Students’ perceptions of how the instructional language supported or constrained academic work (measured by the Language of Study Effects scale).

3.2. Participants

3.3. Instruments

3.4. Procedure

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Validation (CFA)

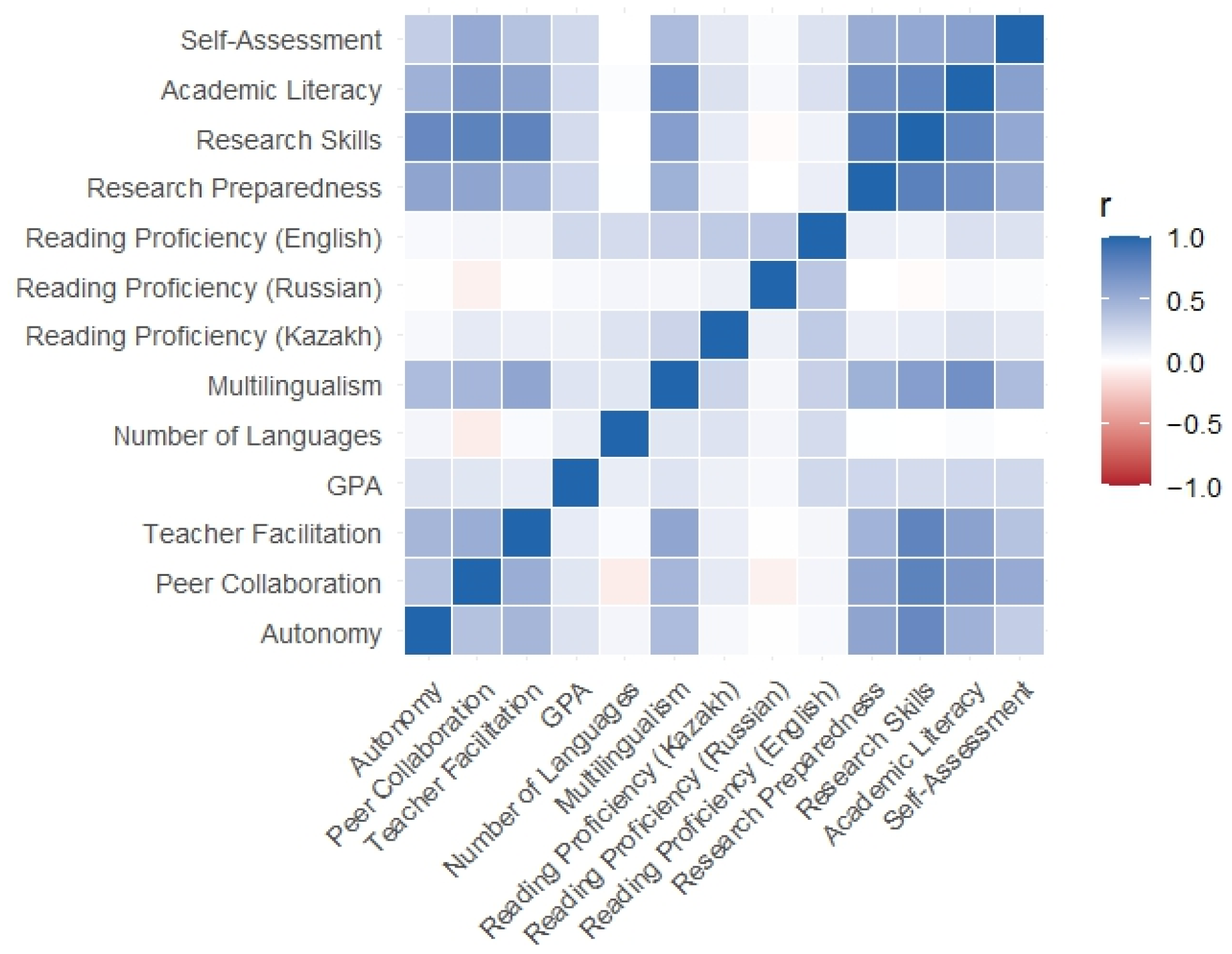

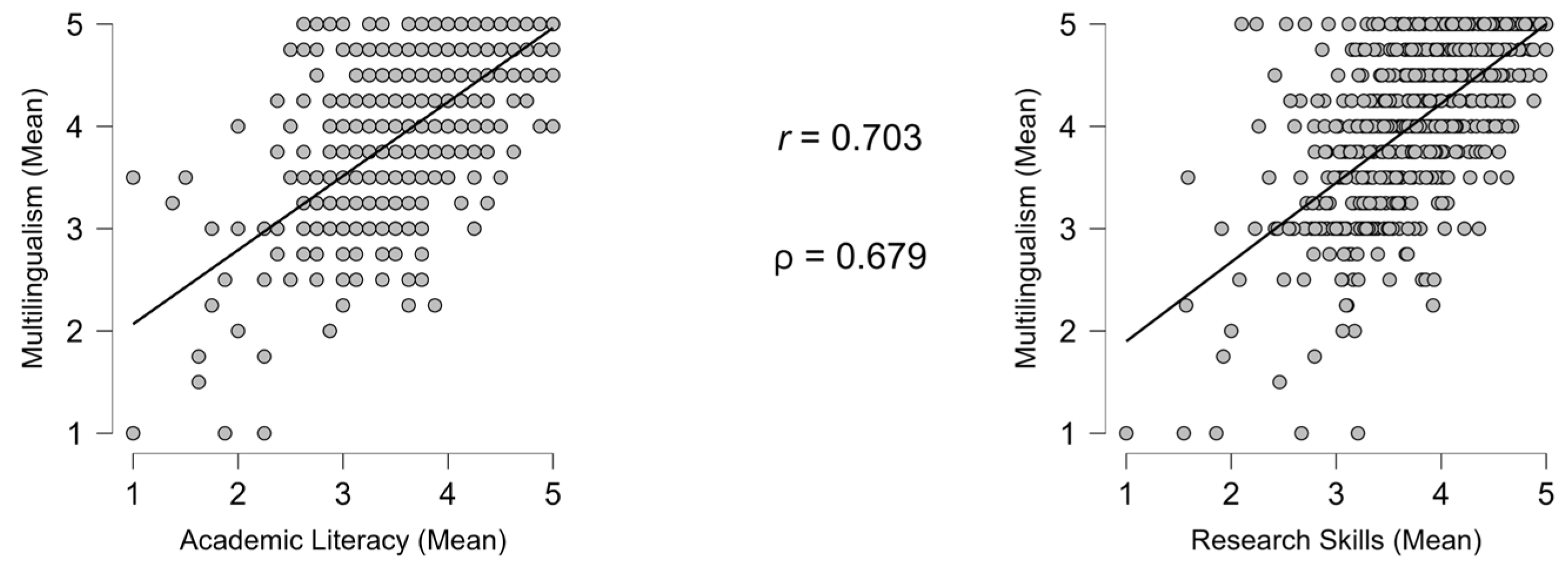

4.2. Correlation Analysis

4.3. Test of Hypotheses

5. Discussion

5.1. Research Skills and Academic Literacy in a Multilingual Context

5.2. Influence of Institutional and Pedagogical Factors

5.3. Language of Instruction and Multilingualism

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| DWLS | Diagonally Weighted Least Squares |

| EMI | English-Medium Instruction |

| GFI | Goodness of Fit Index |

| HE | Higher Education |

| HEIs | Higher Educational Institutions |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio of Correlations |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficients |

| RBL | Research-based learning |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| STEM | Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics |

| TLI | The Tucker–Lewis Index |

References

- Aarar, M., & Pérez Valverde, C. (2025). Enhancing evidence-based writing and critical thinking skills of high school students by implementing a debating-via-zoom approach. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agricola, B. T., Prins, F. J., van der Schaaf, M. F., & van Tartwijk, J. (2018). Teachers’ diagnosis of students’ research skills during the mentoring of the undergraduate thesis. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 26(5), 542–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaba, M. B. (2025). Proposing a linguistic repertoires perspective in multilingual higher education contexts. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, (36). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisaari, J., Heikkola, L. M., Commins, N., & Acquah, E. O. (2019). Monolingual ideologies confronting multilingual realities: Finnish teachers’ beliefs about linguistic diversity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 80, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminova, L., Saurbayev, R., & Yerekhanova, F. (2025). The psychological aspects of bilingualism and multilingualism: Current issue, challenges, and perspectives. Annali d’Italia, 63, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, S. R., Banu, S. B., Chandini, S., Thulasi, V. V. Y. R., Jyothi, M. K., & Nusari, M. S. (2022). Assessment of research skills in undergraduate students. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(6), 9579–9586. [Google Scholar]

- Begaliyeva, S., Shmakova, E., & Zhunisbayeva, A. (2025). Creation of a collaborative “school-university” environment to support research activities in schools. Education Sciences, 15(1), 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran-Palanques, V., Liu, J. E., & Lin, A. M. Y. (2024). Translanguaging in language teacher education. In Z. Tajeddin, & T. S. Farrell (Eds.), Handbook of language teacher education. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, P. (2011). Teaching and researching: Autonomy in language learning (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieschke, K. J., Bishop, R. M., & Garcia, V. L. (1996). The utility of the research self-efficacy scale. Journal of Career Assessment, 4(1), 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, S., & Liu, Y. (2013). Chinese university teachers’ research engagement. TESOL Quarterly, 47(2), 270–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughey, C., & McKenna, S. (2016). Academic literacy and the decontextualised learner. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning (CriSTaL), 4(2), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canagarajah, A. S. (2013). Translingual practice: Global Englishes and cosmopolitan relations. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2013). Towards a plurilingual approach in English language teaching: Softening the boundaries between languages. TESOL Quarterly, 47, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compagnucci, L., & Spigarelli, F. (2020). The third mission of the university: A systematic literature review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 161, 120284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. (2008). Teaching for transfer: Challenging the two solitudes assumption in bilingual education. In N. H. Hornberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of language and education. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauletkeldyyeva, A., Smagambet, B., Saliyeva, A., Baigabylov, N., & Jamaliyeva, G. (2024). Models and practices of the introduction of multilingualism (comparative sociological analysis). Social Identities, 30(6), 568–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Henau, J. (2024). Academic skills literature review. Centre for Teaching and Learning, University of Oxford. Available online: https://www.ctl.ox.ac.uk/academic-skills-literature-review (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Doebler, R. (2025). A social practices lens to explore an academic foundation programme in Kazakhstan. In M. Bedeker, T. M. Makoelle, & S. A. Manan (Eds.), Exploring academic writing as social practice. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, R. (1994). Collective scaffolding in second language learning. In J. P. Lantolf, & G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskian approaches to second language research (pp. 33–56). Ablex. [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, J. (2021). Translanguaging in action: Pedagogy that elevates. ORTESOL Journal, 38, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Duman, S. (2024). Education reforms in Kazakhstan: International integration and nationalization efforts. In B. Akgün, & Y. Alpaydın (Eds.), Global agendas and education reforms. Maarif global education series. Palgrave Macmillan. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-97-3068-1_3 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism, and education. Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R. M. (2023). Using cooperative learning to enhance students’ learning and engagement during inquiry-based science. Education Sciences, 13(12), 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, M., Jenkins, A., & Lea, J. (2014). Developing research-based curricula in college-based higher education. Higher Education Academy (Advance HE). Available online: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/developing-research-based-curricula-college-based-higher-education (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Hwami, M. (2024). A geopolitics of knowledge analysis of higher education internationalisation in Kazakhstan. British Educational Research Journal, 50(2), 676–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K., & Jiang, F. (2019). Academic discourse and global publishing: Disciplinary persuasion in changing times. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabassova, L. (2020). Understanding trilingual education reform in Kazakhstan: Why is it stalled? In D. Egéa (Ed.), Education in Central Asia (Vol. 8). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keser Aschenberger, F., & Pfeffer, T. (2021). Concept of research literacy in academic continuing education: A systematic review. European Journal of University Lifelong Learning, 5(1), 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koptleuova, K., Karagulova, B., Zhumakhanova, A., Kondybay, K., & Salikhova, A. (2023). Multilingualism and the current language situation in the Republic of Kazakhstan. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 11(3), 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuada, J. (2012). Research methodology: A project guide for university students. Samfundslitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchumova, G., & Mukhamejanova, D. (2025). Challenges in developing research-based teacher education in Kazakhstan. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labouta, H. I., Kenny, N. A., Dyjur, P., Li, R., Anikovskiy, M., Reid, L. F., & Cramb, D. T. (2019). Investigating the alignment of intended, enacted, and perceived learning outcomes in an authentic research-based science program. The Canadian Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantolf, J. P., & Poehner, M. E. (2011). Dynamic assessment in the classroom: Vygotskian praxis for second language development. Language Teaching Research, 15(1), 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantolf, J. P., & Poehner, M. E. (2014). Sociocultural theory and the pedagogical imperative in L2 Education: Vygotskian praxis and the research/practice divide (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, M. R., & Street, B. V. (2006). Student writing in higher education: An academic literacies approach. Studies in Higher Education, 23(2), 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraru, M., Bakker, A., Akkerman, S., Zenger, L., Smit, J., & Blom, E. (2025). Translanguaging within and across learning settings: A systematic review focused on multilingual children with a migration background engaged in content learning. Review of Education, 13(2), e70069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otheguy, R., García, O., & Reid, W. (2015). Clarifying translanguaging and deconstructing named languages: A perspective from linguistics. Applied Linguistics Review, 6(3), 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, D. K., Martínez, R. A., Mateus, S. G., & Henderson, K. L. (2014). Reframing the debate on language separation: Toward a vision for translanguaging pedagogies in the dual language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 98, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirhonen, H. (2023). University students’ language learner beliefs and identities in the context of multilingual pedagogies in higher education [Doctoral dissertation, University of Jyväskylä]. Available online: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-39-9277-4 (accessed on 17 September 2025).

- Qian, Y., & Daiute, C. (2025). Peer collaboration to support Chinese immigrant children’s Chinese heritage language use and learning in New York. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M. A., Khaskheli, A., Qureshi, J. A., Raza, S. A., & Yousufi, S. Q. (2023). Factors affecting students’ learning performance through collaborative learning and engagement. Interactive Learning Environments, 31(14), 2371–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabin, E., Kalman, Y. M., & Kalz, M. (2019). The cathedral’s ivory tower and the open education bazaar—Catalyzing innovation in the higher education sector. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 35(3), 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakkeer, V. (2023). Empowering higher education: The vital role of research skills in academic excellence. International Journal of Educational Research and Development, 5(1), 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y. (2023). Increasing critical language awareness through translingual practices in academic writing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 62, 101229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (2002). Talking it through: Two French immersion learners’ response to reformulation. International Journal of Educational Research, 37(3–4), 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajik, M. A., Manan, S. A., Arvatu, A.-C., & Shegebayev, M. (2024). Growing pains: Graduate students grappling with English medium instruction in Kazakhstan. Asian Englishes, 26(1), 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Walt, C. (2013). Multilingual higher education: Beyond English-medium orientations (Vol. 91). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (Vol. 86). Original work was published in 1930–1934. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, W. R., & Watson, S. L. (2013). Exploding the ivory tower: Systemic change for higher education. TechTrends, 57, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weideman, A. (2003). Assessing and developing academic literacy. Per Linguam, 19(1–2), 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingate, U. (2015). Academic literacy and student diversity: The case for inclusive practice. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Yermekova, T. N., Ryskulbek, D., Azimova, G., Kapalbek, B., & Mawkanuli, T. (2024). Language instruction in Kazakhstan’s higher education: A critical examination. Novitas-ROYAL (Research on Youth and Language), 18(1), 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumay, N., Tazhibayeva, S., Shaldarbekova, A., Jabasheva, B., Naimanbay, A., & Sandybayeva, A. (2021). Multilingual education in the Republic of Kazakhstan: Problems and prospects. Social Inclusion, 9(1), 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Programme Level | National Universities n (%) | Regional Universities n (%) | Private Universities n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bachelor | 90 (13) | 481 (69.5) | 23 (3.3) | 594 (85.8) |

| Master | 66 (9.6) | 31 (4.5) | 1 (0.1) | 98 (14.2) |

| Total | 156 (22.6) | 512 (74) | 24 (3.4) | 692 (100) |

| Factor | Standardized Loadings (Range) | R2 (Range) | AVE | Reliability (ω) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | 0.96–1.13 | 0.50–0.70 | 0.60 | 0.84 |

| Research Preparedness | 0.98–1.08 | 0.55–0.60 | 0.59 | 0.90 |

| Peer Collaboration | 0.93–1.11 | 0.51–0.74 | 0.64 | 0.93 |

| Teacher Facilitation | 1.00–1.01 | 0.69–0.82 | 0.81 | 0.92 |

| Language of Instruction | n | Bachelor (n, %) | Master (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | 102 | 63 (61.8%) | 39 (38.2%) |

| Kazakh | 303 | 258 (85.1%) | 45 (14.9%) |

| Russian | 287 | 273 (95.1%) | 14 (4.9%) |

| Total | 692 | 594 | 98 |

| Model | Predictors Included | AIC | BIC | R2 | ΔF | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 0 | Intercept only | 1985.14 | 1998.87 | – | – | – |

| Model 1 | +Multilingualism | 1791.49 | 1811.56 | 0.37 | 412.56 | <0.001 *** |

| Model 2 | +Language of Instruction | 1788.13 | 1814.53 | 0.37 | 2.40 | 0.092 |

| Model 3 | +Reading Proficiency (Kazakh, Russian, English) | 1787.54 | 1820.28 | 0.38 | 2.85 | 0.037 * |

| Model 4 | +Programmes Level (Bachelor/Master) | 1789.11 | 1828.19 | 0.38 | 0.69 | 0.406 |

| Predictor | Estimate (β) | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.511 | 0.129 | 11.74 | <0.001 *** |

| Multilingualism | 0.556 | 0.027 | 20.10 | <0.001 *** |

| Language of Instruction: Kazakh | 0.078 | 0.067 | 1.16 | 0.246 |

| Language of Instruction: Russian | 0.040 | 0.075 | 0.54 | 0.592 |

| Reading Proficiency (Kazakh) | −0.019 | 0.027 | −0.71 | 0.478 |

| Reading Proficiency (Russian) | −0.009 | 0.023 | −0.40 | 0.684 |

| Reading Proficiency (English) | −0.061 | 0.025 | −2.35 | 0.019 * |

| Programme Level (Master) | 0.052 | 0.063 | 0.83 | 0.406 |

| Model | Predictors Included | AIC | BIC | R2 | ΔModel (ANOVA) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 0 | Intercept only | 1592.17 | 1601.25 | – | – | – |

| Model 1 | +Multilingualism | 1121.66 | 1135.28 | 0.49 | Model 1 vs. Model 0 | <0.001 *** |

| Model 2 | +Language of Instruction (Kazakh, Russian) | 1124.73 | 1147.42 | 0.49 | Model 2 vs. Model 1 | 0.629 |

| Model 3 | +Reading Proficiency (Kazakh, Russian, English) | 1130.23 | 1166.55 | 0.49 | Model 3 vs. Model 2 | 0.921 |

| Model 4 | +Programme Level (Bachelor/Master) | 1128.56 | 1169.42 | 0.49 | Model 4 vs. Model 3 | 0.057 |

| Predictor | Estimate (β) | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.927 | 0.131 | 7.046 | <0.001 *** |

| Multilingualism | 0.687 | 0.028 | 24.527 | <0.001 *** |

| Language of Instruction: Kazakh | −0.004 | 0.069 | −0.058 | 0.954 |

| Language of Instruction: Russian | 0.074 | 0.078 | 0.959 | 0.338 |

| Reading Proficiency (Kazakh) | 0.020 | 0.027 | 0.713 | 0.476 |

| Reading Proficiency (Russian) | −0.007 | 0.024 | −0.310 | 0.757 |

| Reading Proficiency (English) | −0.020 | 0.026 | −0.749 | 0.454 |

| Programme Level (Master) | 0.122 | 0.064156 | 1.908 | 0.0568 † |

| Outcome Variable | Language of Instruction | n | M | SD | df | F | p | η2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | Kazakh | 303 | 4.1 | 0.8 | 2, 689 | 1.01 | 0.36 | – |

| Russian | 287 | 4.0 | 0.7 | |||||

| English | 102 | 3.9 | 1.0 | |||||

| Research Preparedness & Confidence | Kazakh | 303 | 3.9 | 0.7 | 2, 689 | 3.38 | 0.03 | 0.009 |

| Russian | 287 | 3.7 | 0.7 | |||||

| English | 102 | 3.8 | 0.8 |

| Predictor | Estimate (β) | SE | z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of languages known | −0.011 | 0.085 | −0.13 | 0.900 |

| Peer Collaboration | 1.141 | 0.103 | 11.09 | <0.001 *** |

| Teacher Facilitation | 0.272 | 0.107 | 2.55 | 0.011 * |

| Autonomy | 0.185 | 0.104 | 1.78 | 0.075 |

| Academic performance | 0.642 | 0.145 | 4.43 | <0.001 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Baimanova, L.; Gazdiyeva, B.; Althonayan, A.; Zhumagulova, Y.; Kalzhanova, A. Research Skills and Academic Literacy in Multilingual Higher Education: The Case of Kazakhstan. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010021

Baimanova L, Gazdiyeva B, Althonayan A, Zhumagulova Y, Kalzhanova A. Research Skills and Academic Literacy in Multilingual Higher Education: The Case of Kazakhstan. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(1):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010021

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaimanova, Lazzat, Bella Gazdiyeva, Abraham Althonayan, Yekaterina Zhumagulova, and Anar Kalzhanova. 2026. "Research Skills and Academic Literacy in Multilingual Higher Education: The Case of Kazakhstan" Education Sciences 16, no. 1: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010021

APA StyleBaimanova, L., Gazdiyeva, B., Althonayan, A., Zhumagulova, Y., & Kalzhanova, A. (2026). Research Skills and Academic Literacy in Multilingual Higher Education: The Case of Kazakhstan. Education Sciences, 16(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010021