An SSI-Based Instructional Unit to Enhance Primary Students’ Risk-Related Decision-Making

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Science Competency and Socioscientific Issues

1.2. Socioscientific Decision-Making

1.3. Dealing with Risks in SSI Education

1.4. The Purpose of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instructional Unit

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

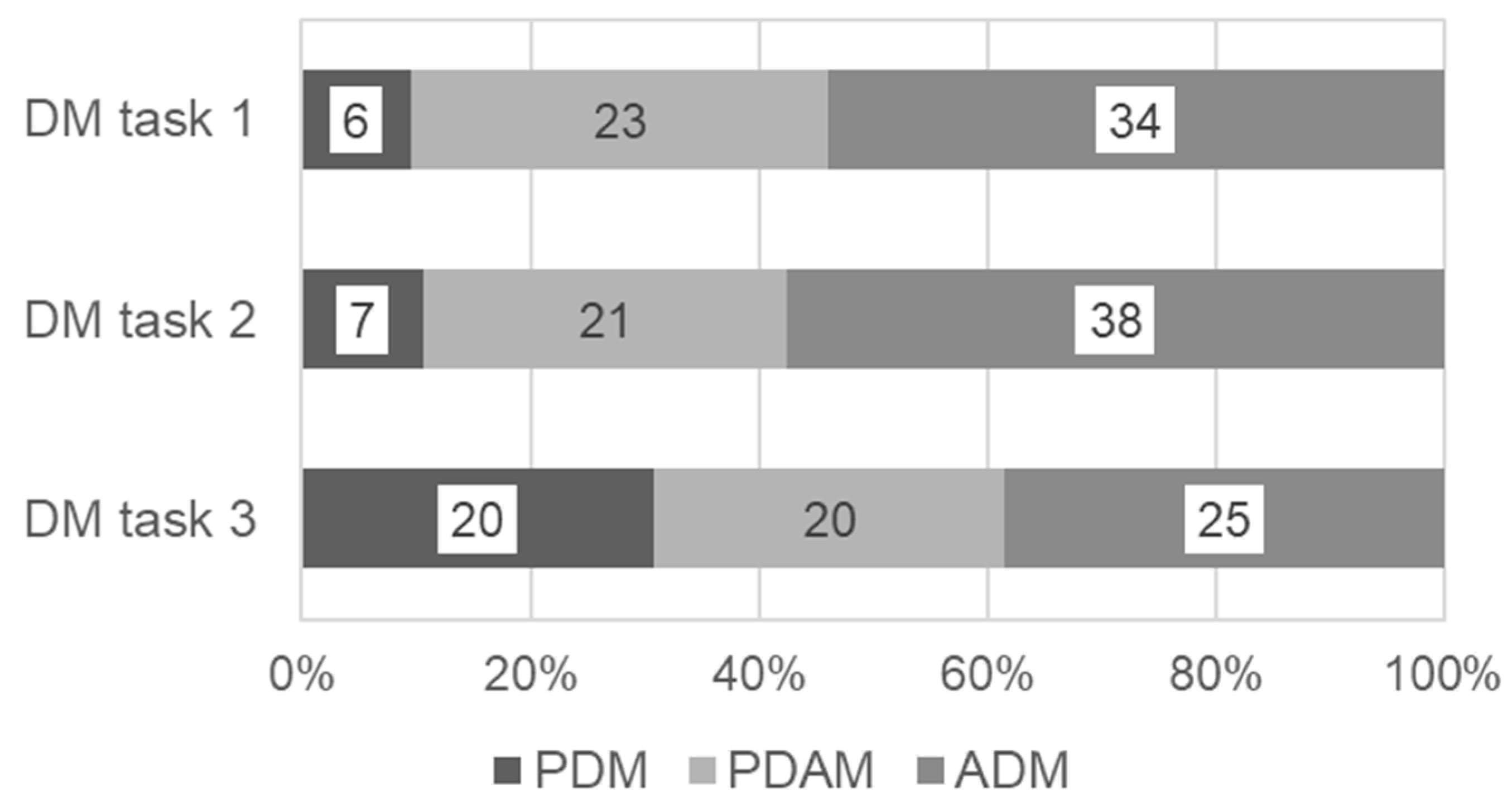

3.1. Students’ Positions

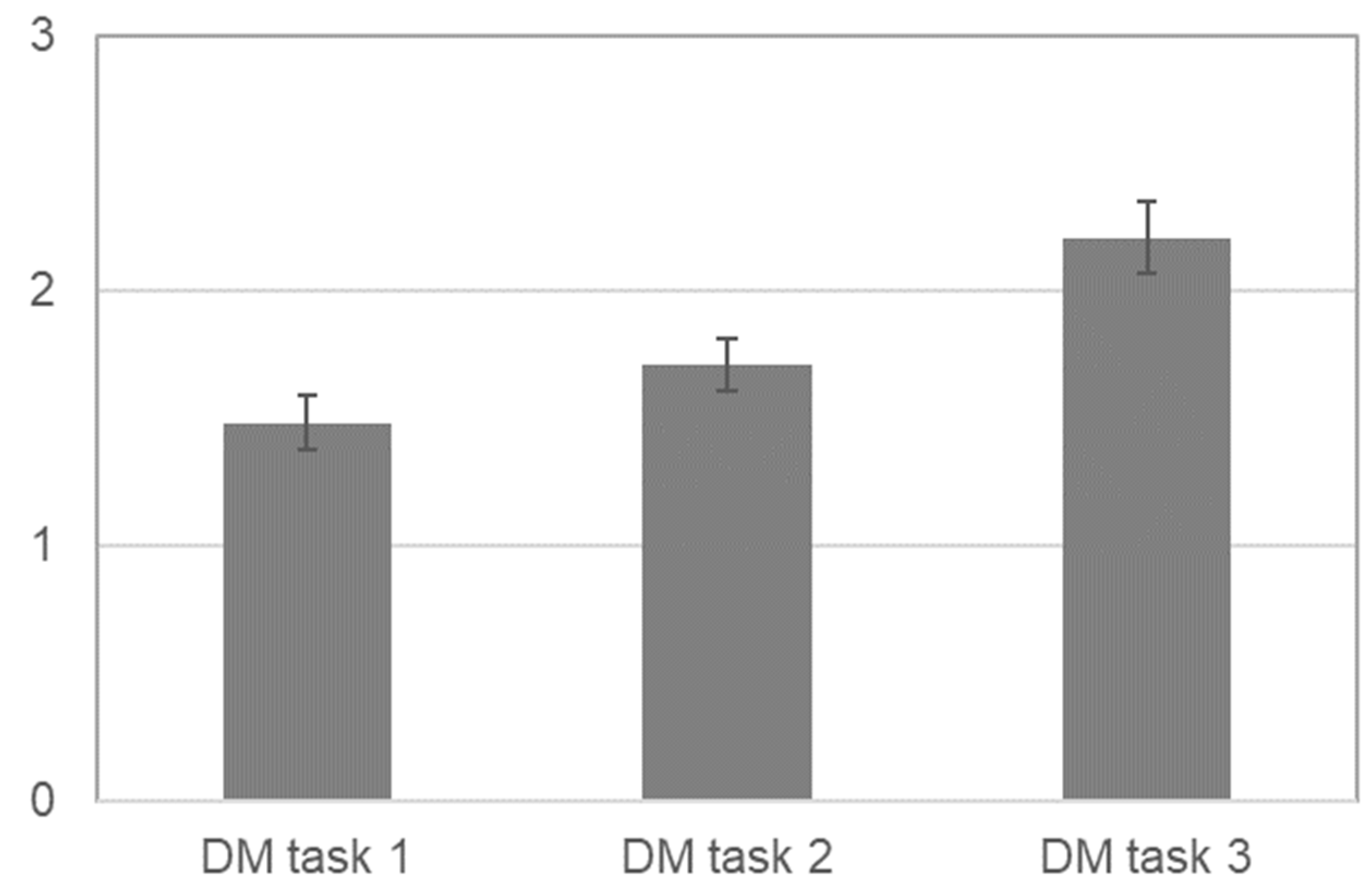

3.2. Analysis of the Quality of Students’ Decision-Making Arguments (RQ1)

3.3. Change in Risk–Benefit Emphasis Ratings (RQ2)

3.4. Students’ Attitudes Toward Critical Thinking and Risk (RQ3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of the Findings

4.2. Educational Significance and Future Directions

4.3. Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aven, T. (2024). Risk literacy: Foundational issues and its connection to risk science. Risk Analysis, 44(5), 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencze, L. (2017). Science and technology education promoting wellbeing for individuals, societies & environments (STEPWISE). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Birdsall, S. (2022). Socioscientific issues, scientific literacy, and citizenship: Assembling the puzzle pieces. In Y.-S. Hsu, R. Tytler, & P. J. White (Eds.), Innovative approaches to socioscientific issues and sustainability education: Linking research to practice (pp. 235–250). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C. (2009). Risk and school science education. Studies in Science Education, 45(2), 205–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauer, J. M., Kirby, C. K., & Sorensen, A. E. (2025). Defining students’ socioscientific issues classroom decision-making components and practice proficiencies. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research, 7(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauer, J. M., Lute, M. L., & Straka, O. (2017). Indicators of informal and formal decision-making about a socioscientific issue. International Journal of Education in Mathematics, Science and Technology, 5(2), 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauer, J. M., Sorensen, A. E., & Jimenez, P. C. (2022). Using structured decision making in the classroom to promote information literacy in the context of decision making. Journal of College Science Teaching, 51(6), 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S. C., Hsu, Y. S., & Lin, S. S. (2019). Conceptualizing socioscientific decision making from a review of research in science education. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 17(3), 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J., & Hammann, M. (2017). Risk in science instruction: The realist and constructivist paradigms of risk. Science & Education, 26(7–9), 749–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Högström, P., Gericke, N., Wallin, J., & Bergman, E. (2025). Teaching socioscientific issues: A systematic review. Science & Education, 34(5), 3079–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, P. C., Zwickle, A., & Dauer, J. M. (2024). Defining and describing students’ socioscientific issues tradeoff practices. International Journal of Science Education, Part B, 14(3), 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, S. (2020). No child too young: A teacher research study of socioscientific issues implementation at the elementary level. In W. Powell (Ed.), Socioscientific issues-based instruction for scientific literacy development (pp. 1–30). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Kanazawa, N., Tanaka, Y., Koyama, K., Naitou, H., Ikawa, M., & Nakayama, Y. (2020). Measurement scales of risk literacy for risk education. Japanese Journal of Risk Analysis, 29(4), 243–249. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpudewan, M., & Roth, W. M. (2018). Changes in primary students’ informal reasoning during an environment-related curriculum on socio-scientific issues. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 16(3), 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, L., Zangori, L., Sadler, T. D., & Friedrichsen, P. (2020). Integrating scientific modeling and socio-scientific reasoning to promote scientific literacy. In W. Powell (Ed.), Socioscientific issues-based instruction for scientific literacy development (pp. 31–54). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G., Ko, Y., & Lee, H. (2020). The effects of community-based socioscientific issues program (SSI-COMM) on promoting students’ sense of place and character as citizens. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 18(3), 399–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. U., Kang, D., & Kim, C. J. (2025). Analysing the quality of risk-focused socio-scientific arguments on nuclear power using a risk-benefit oriented model. Research in Science Education, 55(5), 1205–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolstø, S. D. (2006). Patterns in students’ argumentation confronted with a risk-focused socio-scientific issue. International Journal of Science Education, 28(14), 1689–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumi, T., Murase, M., & Takeda, A. (2016). Measurement of critical thinking attitude in fifth- through ninth-graders: Relationship to reflective predisposition, perceived academic competence and the educational program. Japan Journal of Educational Technology, 40(1), 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H., & Ko, Y. (2025). ENACT project as a pedagogical approach for cultivating awareness and willingness to act on socioscientific issues. In J. L. Bencze (Ed.), Building networks for critical and altruistic science education (pp. 443–465). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H., Park, Y., Lee, H., Mun, K., & Hwang, Y. (2024). Exploring educational models for integrating socioscientific issues (SSI) with risk education. Journal of the Korean Association for Science Education, 44(4), 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaou, C. T., Evagorou, M., & Lymbouridou, C. (2015). Elementary school students’ emotions when exploring an authentic socio-scientific issue through the use of models. Science Education International, 26(2), 240–259. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2025). PISA 2025 science framework. Available online: https://pisa-framework.oecd.org/science-2025/ (accessed on 12 January 2026).

- Romine, W. L., Sadler, T. D., & Kinslow, A. T. (2017). Assessment of scientific literacy: Development and validation of the Quantitative Assessment of Socio-Scientific Reasoning (QuASSR). Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 54(2), 274–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundgren, C. J., Eriksson, M., & Rundgren, S.-N. C. (2016). Investigating the intertwinement of knowledge, value, and experience of upper secondary students’ argumentation concerning socioscientific issues. Science & Education, 25(9–10), 1049–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, T. D. (2004). Informal reasoning regarding socioscientific issues: A critical review of research. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 41(5), 513–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenk, L., Hamza, K., Arvanitis, L., Lundegård, I., Wojcik, A., & Haglund, K. (2021). Socioscientific issues in science education: An opportunity to incorporate education about risk and risk analysis? Risk Analysis, 41(12), 2209–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparks, R. A., Johnson, P. C., Kim, C. K., & Dauer, J. M. (2022). Structured decision-making as a context for socioscientific argumentation. Educational Sciences, 12(10), 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., & Tsai, C. (2007). High school students’ informal reasoning on a socio-scientific issue: Qualitative and quantitative analyses. International Journal of Science Education, 29(9), 1163–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidler, D. L. (2014). Socioscientific issues as a curriculum emphasis: Theory, research, and practice. In N. G. Lederman, & S. K. Abell (Eds.), Handbook of research on science education (Vol. II, pp. 697–726). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| Phase | Contents and Learning Activities |

|---|---|

| 1. Information search | Students learned content knowledge and background knowledge regarding the focal issue. |

| |

| The first decision-making task | |

| 2. Risk management practices |

|

| The second decision-making task | |

| Students generated risk mitigation measures to manage the risks and examined them with the whole class. | |

| The third decision-making task |

| Categories | Benefits | Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Economy |

|

|

| Ecology | Helps prevent overfishing and contributes to the conservation of fishery resources and marine ecosystems. | May disrupt the existing ecological balance. |

| Safety | The technology can be applied to the medical and pharmaceutical fields. |

|

| Score | Description | Examples of Students’ Descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Contained only a simple claim, without any justification. | Providing detailed information about genome-edited fish ensures a certain level of safety, and if it tastes good, that is all that matters. |

| 1 | Included a claim supported by risk knowledge. | I oppose the development and marketing of genome-edited fish [Claim]. My reasons are that it is unclear whether they are safe for continued consumption [Risk] 1, they could potentially disrupt the ecological balance [Risk], and genome editing may cause distress to the animals [Risk]. Furthermore, verifying the safety of genome-edited fish will take time, and during that period, retailers’ sales may decline [Risk]. |

| 2 | Included a claim and justification with both risk and benefit knowledge. | I oppose the development and marketing of genome-edited fish [Claim]. The reason is that it may disrupt the balance of ecosystems [Risk]. For example, while “meaty sea bream” may offer benefits such as increased edible portions [Benefit] 2, abnormalities could occur in the fish’s body [Risk]. Moreover, even if the risk of editing failure is significantly reduced [Benefit], there remains a slight possibility of failure [Risk]. |

| 3 | Included a claim, risk knowledge, and corresponding risk mitigation. | I was concerned that fish might escape from aquaculture cages and disrupt the ecosystem [Risk], but if the cages are built on land, the fish will not escape [Mitigation] 3. I was also worried that patents might lead to market monopolisation [Risk], but if the state regulates the quantity that a single company may sell, monopolisation will not occur [Mitigation]. Even if research costs are high [Risk], state subsidies for researchers could promote further studies [Mitigation]. Therefore, I support genome editing research that can help address the global food crisis [Benefit]. |

| Means 1 | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| DM task 1 | 6.31 | 2.59 |

| DM task 2 | 6.47 | 2.56 |

| DM task 3 | 4.78 | 2.75 |

| Means | SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Pro-Development and Marketing (PDM) | 2.15 | 2.03 |

| Pro-Development/Anti-Marketing (PDAM) | 5.30 | 1.53 |

| Anti-Development and Marketing (ADM) | 6.92 | 1.89 |

| α | Range | Means | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical thinking attitude (Scale) | 0.633 | 3–5 | 4.48 | 0.512 |

| Interests in SSI (Scale) | 0.733 | 1–5 | 4.40 | 0.708 |

| Risk attitudes | ||||

| Risk tolerance | - | 1–5 | 4.06 | 1.08 |

| Zero-risk mind-set | - | 1–5 | 3.49 | 1.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sakamoto, M.; Yamaguchi, E.; Yamamoto, T.; Matano, M.; Ohmido, N.; Murayama, R. An SSI-Based Instructional Unit to Enhance Primary Students’ Risk-Related Decision-Making. Educ. Sci. 2026, 16, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010143

Sakamoto M, Yamaguchi E, Yamamoto T, Matano M, Ohmido N, Murayama R. An SSI-Based Instructional Unit to Enhance Primary Students’ Risk-Related Decision-Making. Education Sciences. 2026; 16(1):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010143

Chicago/Turabian StyleSakamoto, Miki, Etsuji Yamaguchi, Tomokazu Yamamoto, Motoaki Matano, Nobuko Ohmido, and Rumiko Murayama. 2026. "An SSI-Based Instructional Unit to Enhance Primary Students’ Risk-Related Decision-Making" Education Sciences 16, no. 1: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010143

APA StyleSakamoto, M., Yamaguchi, E., Yamamoto, T., Matano, M., Ohmido, N., & Murayama, R. (2026). An SSI-Based Instructional Unit to Enhance Primary Students’ Risk-Related Decision-Making. Education Sciences, 16(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci16010143