You Cannot Change the System Without Looking Inward First: Three California Preparation Programs with Coaching That Makes a Difference

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

3.1. Programs Studied

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Analytic Approach

4. Findings for Research Question 1: Conceptualization and Design

4.1. UCLA-PLI

4.1.1. Program Concept

4.1.2. Role of Coaching

As a new school leader, my district assigned me a leadership coach. I clearly remember our conversation and the offered strategies to help address the racial tensions at my school. During our coaching conversation, she expressed sympathy, expressing how sorry she was that our students and families had to endure such awful behavior. She started asking me questions to help me reflect on the situation and think of ways to move forward. However, as the conversation progressed, I found myself becoming increasingly angry and frustrated. I started to view my district coach, a white woman, with contempt and resentment. As an African American school leader, I thought to myself, “What can she tell me about dealing with issues of race? I don’t need an “I’m sorry”. There is not a strategy that can fix what I am feeling.” I was grappling with deep emotional pain and this conversation seemed focused on something far removed from what I truly needed. I realized I needed something different, something more.

4.2. UCB-PLI

4.2.1. Program Concept

4.2.2. Role of Coaching

4.3. CSUF-LEAD

4.3.1. Program Concept

4.3.2. Role of Coaching

5. Findings for Research Question 2: Cross-Programmatic Themes

5.1. Promote Bringing One’s Whole Self into the Room

We were both invested in the equity issues surrounding our English Language Learners (ELL), as we had personally experienced being English Learners during our schooling. Our shared, but unique experiences, drove our commitment to support our current ELL. Our actions formed out of the underlying equity concerns raised by Juan, a 4th grade teacher who I was coaching. Juan shared his personal story about how his older brother, classified as a Spanish speaker at home, had a very different school experience than he did as someone who was enrolled in school as an English speaker. Both Juan and I were personally invested in the equity issue because of our experiences as an EL student.

5.2. Center and Model Vulnerability and Relational Trust

The autobiographies generated a sense of trust with the instructors, including across racial lines.So much of our work is about decentering the narratives of people like me. As I embarked on modeling an autobiography at our first day of class in August 2021, I told the candidates—candidates of color and many who faced conditions of extreme poverty in childhood—that I was absolutely terrified. But by the end, the whole tone in the room had shifted. [One Latina student] laughed after stammering through, “Jen, I mean Jennifer, I mean Professor Goldstein … oh forget it, you’re Jen now!”.

Data indicate that the autobiographies brought an increased awareness of the impact of White supremacy across the diversity of participants, especially pertaining to the existence of colorism and anti-Blackness across racial groups represented. This awareness makes coaching conversations about colorism, for example, much easier to broach.Racial autobiography is not just who I am, but permission from the system to shout it out. I’m not in the shadows anymore. That’s a huge thing, that they know that in this district, they are affirmed for their own stories, just as we want teachers to affirm kids… I’m really proud of these candidates and their courage to say what needs to be said and do what needs to be done. Their stories, they are so emotional because they know their stories are also the stories of the kids.

5.3. Center Educational Equity and Justice

5.4. Center and Model an Inquiry Stance

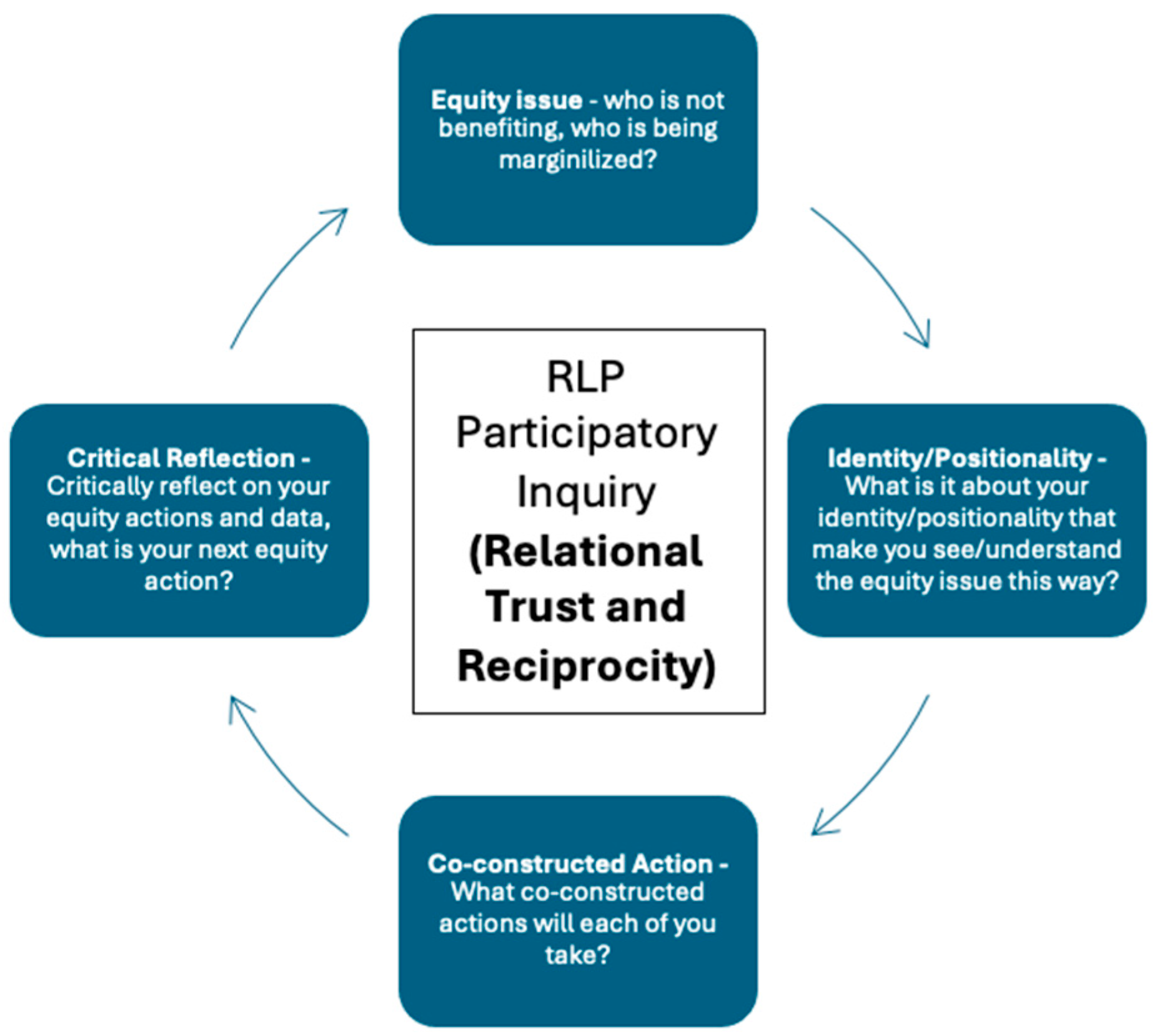

A single strategy cannot address the underlying emotional, cultural, and systemic complexities that perpetuate and sustain inequitable practices and policies. The RLP framework used here functions as an inquiry process that adopts an equity stance and rejects neutrality.A few years ago, we faced a troubling racial incident involving teachers followed by an increase of incidents between students. Fast forward to the present, and through the RLP, both my site administrators joined weekly RLP coaching discussions for a year-long engagement about the presence of racial slurs at our site, examining their frequency, context, and impact. It was during these honest conversations that we decided to explore the possibility of inviting someone to guide us as we leaned into our discomfort around race. The RLP especially helped my principal lean into her discomfort of confronting this long-overlooked topic. It also made her realize that this training can’t be a one-time event. As we discussed during the RLP cycle, “one and done” training creates cosmetic changes and unintended harm. The RLP process has shown us the importance of being in community to ensure we stay active rather than passive, that it’s okay as leaders to not know everything, okay to make mistakes, and to seek help outside our school to initiate these critical conversations.

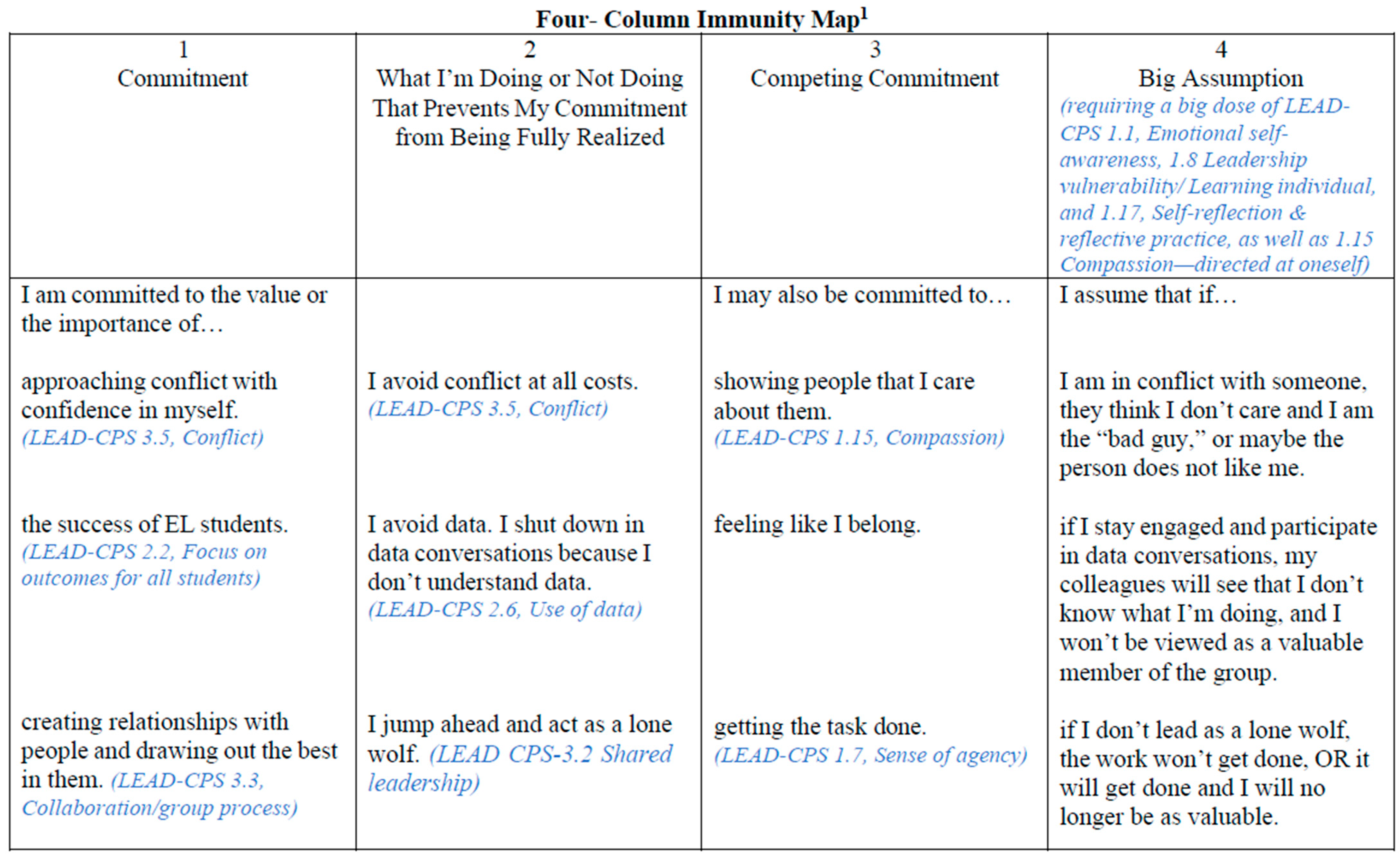

5.5. Ground the Work in Leadership Competencies

A coach is not a therapist. Coaching requires guardrails and we have at times referred coachees to mental health professionals when issues raised go beyond program staff’s expertise. Nonetheless, our data show that an enormous amount can be accomplished just by engaging in highly intentional individual coaching, as well as the fact that certain themes emerge repeatedly across coachees–often by gendered and racialized lines. With Amanda, for example,The immunity map assignment was not just about analyzing our leadership potential, it was about identifying the barriers holding us back and addressing them head on. It was about being vulnerable and honest with ourselves, naming the obstacle and finding the courage to work toward rising above it… It was not until my scheduled one-on-one meeting with our professor that I realized how tightly I had been keeping the lid on… As I waited for the meeting to begin, I noticed that the person whose office we were borrowing had kindly left snacks, water, and tissues for us. I remember thinking, “Why tissues?”.

Amanda’s growth was such that she wrote about her experience with coaching for her masters’ thesis/book chapter (Bryant, 2024).In the coaching conversation, I finally opened the gates to being genuine and vulnerable when answering the questions my professor asked. From my answers, it became clear that my colleagues’ opinions of me weighed more heavily on me than I had let myself realize… My tears—yes, we did need that Kleenex—came from my frustration with myself that, although I try to inspire my students to find their voice and confidence despite what others think, I was doing the exact opposite for myself.

During the fall semester, UCB-PLI students collaborate with their leadership coaches to identify 3 specific leadership goals aligned to competencies in the Leadership Connection Rubric. Together, they craft a coaching plan which includes a theory of action, indicators of progress, and a place for the coach to record notes from coaching interactions across their time in the preparation program. This coaching plan is a way for coaches and aspiring leaders to remain accountable to the identified goals and to ensure that all leadership actions are analyzed using the competencies of the Rubric.I think the Leadership Rubric helps a ton with that, because the first three elements are presence and attitude, identity and relationships, and equity and advocacy. So from the get-go, we’re talking about Who am I? Who do I want to be? And it’s wide open for both of us to talk about. For me, I’m an old white lady. How does that land with you? Then to invite coachees to identify where they are in terms of whatever identities they have.

6. Findings for Research Question 3: Impact of Coaching Focus

6.1. Impact Is Personal as Well as Professional

Even though the racial autobiography was literally the first assignment Lorena completed for the program, its impact followed her and continued to unfold over the course of two years of the program and of coaching. She drew a thread from the Racial Autobiography through subsequent reflections through this final capstone, in ways that centered not only a work identity but aspects of self that were core to her being.In your 30s you will enroll in an administrative credential program. You will once again doubt yourself and your decisions. But on the 2nd class of your 1st year, you will do a project—a racial autobiography—that will change so many things. The autobiography will allow you to see the chapters of your life that you thought were unfinished. It will allow you to go back and heal from some of those moments in time in your life where you felt “stuck.” But most importantly, it will increase your ability to feel, to ask and receive help, to listen and validate. Lore, that autobiography at the end will make you a badass Latina leader! Lore, Si se puede y si se pudo!

6.2. Impact Is Systemic as Well as Individual

Knowing when to invite coachees to lean into discomfort and having the ability to recognize when the coachee’s experience and expertise should be foregrounded in the conversation is a critical learning that many UCB-PLI coaches noted, and one that allows them to generate systems change through powerful coaching conversations.I just feel like [the professional learning sessions are] making me a better-informed coach, that it’s making me able to coach in situations that weren’t necessarily my own experience… it’s just like knowing more, and then being able to have the coaching strategies to say, “Well, tell me more or, wow, that’s a lot to unpack. Do you mind if we stay here with this topic for a while?”

7. Discussion

8. Implications and Conclusion

8.1. Implications for Practice

8.2. Study Limitations and Implications for Future Research

8.3. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aguilar, E. (2013). The art of coaching: Effective strategies for school transformation. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, E. (2020). Coaching for equity: Conversations that change practice. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, E. (2024). Arise: The art of transformational coaching. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, G. L., Herr, K., & Nihlen, A. S. (2007). Studying your own school: An educator’s guide to practitioner action research. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Quigley. (2025, January 30). The power of coaching for school leaders. Available online: https://andersonquigley.com/latest/the-power-of-coaching-for-school-leaders/ (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Arriaga, T. T., Stanley, S. L., & Lindsey, D. B. (2020). Leading while female: A culturally proficient response for gender equity. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belski, B. (2024). Oral language development across the curriculum: Supporting multilingual learners in the arts. In J. Goldstein, N. S. Panero, & M. Lozano (Eds.), Radical university-district partnerships: A framework for preparing justice-focused school leaders. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bhabha, H. K. (2004). The location of culture. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R. E., & Goleman, D. (2007). Emotional and social competency inventory. Hay Group. [Google Scholar]

- Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2013). School leaders matter: Measuring the impact of effective principals. Education Next, 13(1), 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. M. (2021). Holding change: The way of emergent strategy facilitation and mediation. AK Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B. (2018). Dare to lead. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, A. (2024). Stepping out of the shadows. In J. Goldstein, N. S. Panero, & M. Lozano (Eds.), Radical university-district partnerships: A framework for preparing justice-focused school leaders. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk, A., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Campoli, A. K., Darling-Hammond, L., With Podolsky, A., & Levin, S. (2022). Principal learning opportunities and school outcomes: Evidence from California. Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, M. A., & Coggshall, J. G. (2021). Evolution of the principalship: Leaders explain how the profession is changing through a most difficult year (pp. 1–24). National Association of Elementary School Principals, American Institutes for Research. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Inquiry as stance: Practitioner research for the next generation. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2014). California Professional Standards for Educational Leaders (CPSEL). Available online: https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/educator-prep/standards/cpsel-booklet-2014.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Cosner, S., & De Voto, C. (2023). Using leadership coaching to strengthen the developmental opportunity of the clinical experience for aspiring principals: The importance of brokering the third-party influence. Educational Administration Quarterly, 59(1), 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosner, S., Walker, L., Swanson, J., Hebert, M., & Whalen, S. P. (2018). Examining the architecture of leadership coaching: Considering developmental affordances from multifarious structuring. Journal of Educational Administration, 56(3), 364–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M. E., Levin, S., Leung-Gagné, M., & Tozer, S. (2022). Developing effective principals: What kind of learning matters? (Report). Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillard, C. B. (2012). Learning to (re)member the things we’ve learned to forget: Endarkened feminisms, spirituality, & the sacred nature of research and teaching. Peter Lang Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Drago-Severson, E., & Blum-DeStefano, J. (2016). Tell me so I can hear you: A developmental approach to feedback for educators. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Francois, A., & Quartz, K. (2021). Preparing and sustaining social justice educators. Harvard Press. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, M., & Ishimaru, A. (2017). Equitable leadership on the ground: Converging on high-leverage practices. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 25, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garmston, R. J., & Wellman, B. M. (2016). The adaptive school: A sourcebook for developing collaborative groups. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwright, S. A. (2022). The four pivots: Reimagining justice, reimagining ourselves. North Atlantic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J., Panero, N. S., & Lozano, M. (2024). Radical university-district partnerships: A framework for preparing justice-focused school leaders. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2002). Primal leadership: Realizing the power of emotional intelligence. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. The Wallace Foundation. Available online: http://www.wallacefoundation.org/principalsynthesis (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Grissom, J. A., & Loeb, S. (2011). Triangulating principal effectiveness: How perspectives of parents, teachers, and assistant principals identify the central importance of managerial skills. American Educational Research Journal, 48(5), 1091–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsing, D., Howell, A., Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. (2008). Putting the “development” in professional development: Understanding and overturning educational leaders’ immunities to change. Harvard Educational Review, 78(3), 437–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, J., Gallimore, R., & Stigler, J. W. (2002). A knowledge base for the teaching profession: What would it look like and how can we get one? Educational Researcher, 31(5), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooks, B. (1996). Killing rage: Ending racism. Holt Paperbacks. [Google Scholar]

- Irby, D. J. (2021). Stuck improving. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Isken, J., & Orange, T. (2019). Coaching for equity. The Learning Professional, 40(6), 36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Isken, J., & Orange, T. (2021). Listening to the call: Preparing leaders for schools that students deserve. In A. Francois, & K. Quartz (Eds.), Preparing and sustaining social justice educators (pp. 95–106). Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2001). How the way we talk can change the way we work: Seven languages for transformation. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. New World. [Google Scholar]

- Kincheloe, J. L., McLaren, P., Steinberg, S. R., & Monzó, L. D. (2018). Critical pedagogy and qualitative research: Moving to the bricolage. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (5th ed., pp. 235–260). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, L. (2003). Leadership capacity for lasting school improvement. ASCD. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A. (2024). No one has ever taught me that before, Mr. Lee.: Using strategic inquiry to meet the needs of multilingual learners with writing instruction. In J. Goldstein, N. S. Panero, & M. Lozano (Eds.), Radical university-district partnerships: A framework for preparing justice-focused school leaders. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K., Seashore, K., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). Review of research: How leadership influences student learning. Wallace Foundation. Available online: https://conservancy.umn.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/3414bbd1-cf1c-4182-83e3-34843fb69077/content (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Lencioni, P. (2002). The five dysfunctions of a team: A leadership fable. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- National Board for Professional Teaching Standards. (2018). The teacher leadership competencies. National Education Association and Center for Teaching Quality. Available online: https://www.nea.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/2019%20TLI%20Competency%20Book%20NEA_TLCF_20180824.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2024).

- Orr, M. T., & Orphanos, S. (2011). How graduate-level preparation influences the effectiveness of school leaders: A comparison of the outcomes of exemplary and conventional leadership preparation programs for principals. Education Administration Quarterly, 47(1), 18–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panero, N. S., & Talbert, J. E. (2013). Strategic inquiry: Starting small for big results in education. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Radd, S. I., Givens, G. G., Gooden, M. A., & Theoharis, G. (2021). Five practices for equity-focused school leadership. ASCD. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Flores, C. (2024). Ser como soy: Leading with compassion, empathy, and love. In J. Goldstein, N. S. Panero, & M. Lozano (Eds.), Radical university-district partnerships: A framework for preparing justice-focused school leaders. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. (2015). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Currency Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, C. M. (2010). Transformative leadership: Working for equity in diverse contexts. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(4), 558–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoho, A. R., Barnett, B. G., & Martinez, P. (2012). Examining the preparation of assistant principals through a leadership development program. In S. Conley, & B. S. Cooper (Eds.), Finding, preparing, and supporting school leaders: Critical issues, useful solutions (pp. 163–182). Rowman & Littlefield Education. [Google Scholar]

- Soto, I. (2021). Shadowing multilingual learners. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, S. J., & Gewirtzman, L. (2003). Principal training on the ground: Ensuring highly qualified leadership. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Tanksley, T., & Estrada, C. (2022). Toward a critical race RPP: How race, power and positionality inform research practice partnerships. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 45, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T., Kegan, R., Lahey, L., Lemons, R. W., Garnier, J., Helsing, D., Howell, A., & Rasmussen, H. T. (2006). Change leadership: A practical guide to transforming our schools. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, M. E., & Wojcikiewicz, S. K. (2023). Preparing leaders for deeper learning. Harvard Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. K. (2011). Applications of case study research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. D., O’Doherty, A., & Cunningham, K. M. W. (2022). Redesigning educational leadership preparation for equity. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| UCLA-PLI | CSUF-LEAD | UCB-PLI | |

| Students/Graduates | 23 students (17 female, 6 male) 12 Latinx/Indigenous 4 AAPI 5 AA 2 White/Caucasian | 39 students & graduates (26 female, 13 male) 18 Latinx/Indigenous 11 White/Caucasian 8 AAPI 2 AA | N/A |

| Coaches/Others | 5 coaches (5 female) 2 AA 1 Latina 1 White/Caucasian 1 AAPI | 1 coach (1 White female) + 10 principals & 4 high level district administrators | 10 coaches (8 female, 2 male) 7 White/Caucasian 3 AA |

| Data sources | 46 RLP coaching inquiry cycles and narratives, coaching reflections, and field notes | Semi-structured interviews, observations, documentation from professional training, and written coaching reflections | Work products, field notes from coaching meetings, Masters’ leadership journey thesis, and recorded coaching dialogue |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goldstein, J.; Orange, T.; Sablo Sutton, S. You Cannot Change the System Without Looking Inward First: Three California Preparation Programs with Coaching That Makes a Difference. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091244

Goldstein J, Orange T, Sablo Sutton S. You Cannot Change the System Without Looking Inward First: Three California Preparation Programs with Coaching That Makes a Difference. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091244

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoldstein, Jennifer, Tonikiaa Orange, and Soraya Sablo Sutton. 2025. "You Cannot Change the System Without Looking Inward First: Three California Preparation Programs with Coaching That Makes a Difference" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091244

APA StyleGoldstein, J., Orange, T., & Sablo Sutton, S. (2025). You Cannot Change the System Without Looking Inward First: Three California Preparation Programs with Coaching That Makes a Difference. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091244