Centering Identity and Multilingualism in Educational Leadership Preparation Programs

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What motivated candidates to enter an educational leadership preparation program?

- What did they hope to learn in their educational leadership preparation program?

- What would they have liked to learn in their educational leadership preparation program?

- How are the needs of multilingual learners reflected in the course requirements and the missions of the programs they attended?

- How much of a focus was there on the needs of multilingual learners?

1.1. Educational Leadership Preparation Programs in California

1.2. Background

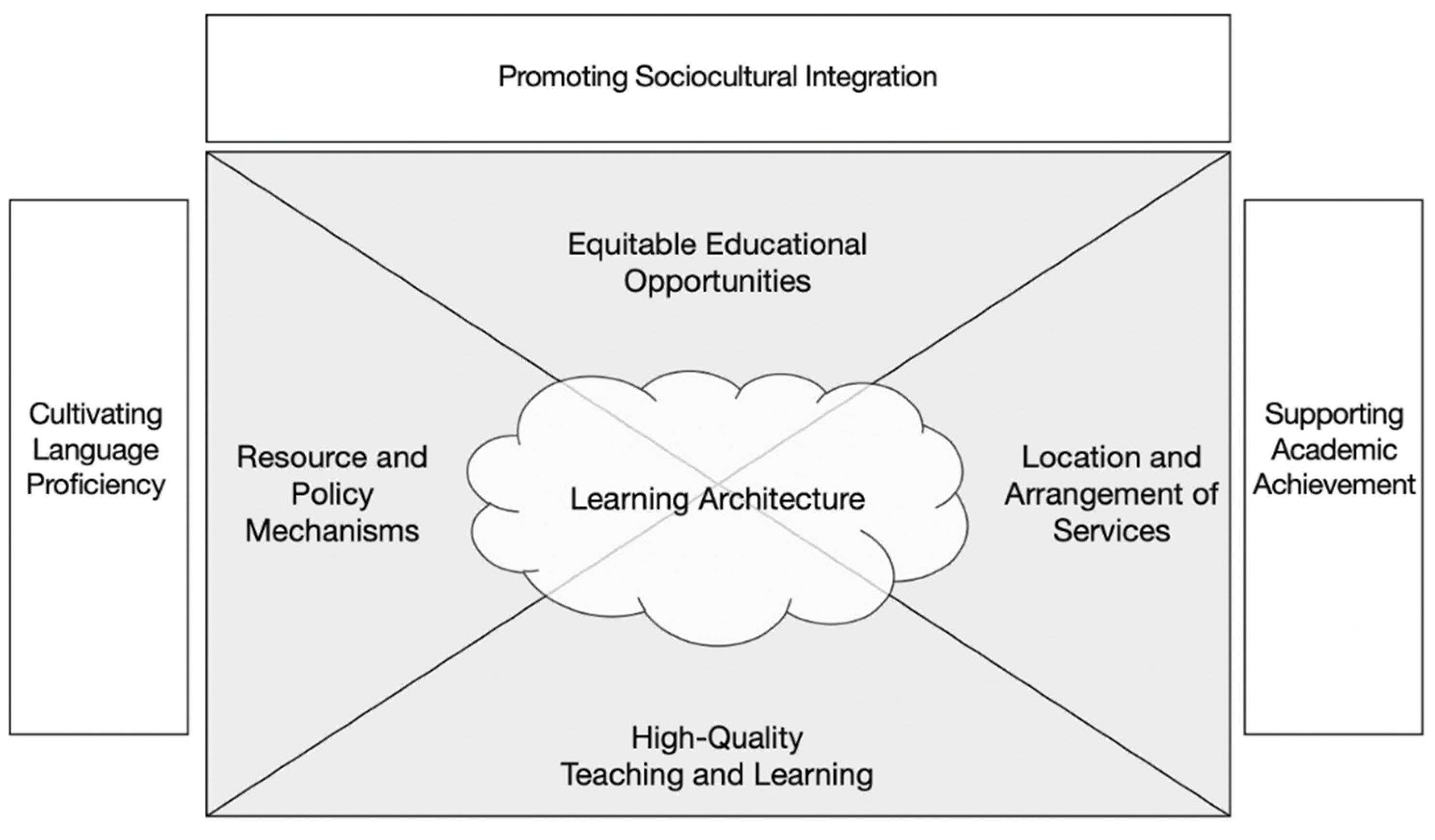

1.3. Conceptual Framework

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Motivation to Enter an Educational Leadership Preparation Program

Similarly, a county level leader who grew up as an EL spoke of her motivation to enter leadership based on her own experiences:When I was in high school, I was part of the Migrant Ed1 program and I experienced injustices. I was sent to the wrong school. I wasn’t in the right classes. I was told I was not meeting the requirements even when I had straight As. My parents didn’t speak the language. At some point, I wanted to get involved in this arena to create more policies and decisions that are more fair and equitable for students.

A mixed-race principal did not grow up as an EL but taught in South America and then in the city of Oakland. As a teacher, he found that he “thrived on bringing people together and connecting with families.” During this time, he joined an equity task force and co-created a class called Student Leaders of Change. Due to those experiences, he sought out an educational leadership preparation program so that he could have “more interactions with families on an equitable level”.I grew up in [this area]. I’m an EL myself and so I’ve been faced with challenges and barriers within the educational system. I went into the classroom with teachers who were non-Spanish speaking. I struggled to get reclassified. My mom who raised me wasn’t really informed. She was a teen mom and wasn’t really engaged. My dad was incarcerated at a young age. She trusted in the school system. She relies on me now that I’m older, but those struggles motivated me to pursue higher education and my career.

It is important to mention that three out of these four leaders are Latine females who were identified as ELs growing up and are being tapped for leadership in their schools.I had been thinking about it, and I feel like people I worked with were planting that seed in me, like, ‘Oh, you’re a good leader.’ and so I went online [to apply]. It was just a good feeling knowing that people I worked with saw me as a leader.

An assistant principal who grew up in Central America shared, “I was interested in changing and challenging myself.” A Latine county level leader elaborated on the desire to challenge herself as part of taking the next step in her career. She is now beginning a doctoral program in Educational Leadership to further her studies.I have always been interested in school programs and being more a part of the things that are going on at a school besides being in the classroom. I always felt like I wanted to get out of the classroom and go help them with the implementation of their Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), or I wanted to be on these committees that were doing things or be a part of the student leadership stuff. I wanted to do more of that.

Leaders also sought out educational leadership preparation programs so that they would have more of an opportunity to make a difference as this Latine district leader shared, “I knew if you want to see change, if you don’t agree with things, then you have to be in a different role. And that’s when I was like, being an administrator would be a great thing.” A mixed race principal from a more privileged background shared that he felt that he could make more of an impact on a systemic level as a school leader instead of staying in the classroom:I enjoy teaching. I love teaching. I love doing this, but I always believe that I need to continue challenging myself and growing. And I don’t think if I’m in my comfort level, I’m not growing as a professional, as a person. This journey towards leadership is not just about the destination but the personal growth and development that comes with it. It’s about pushing yourself out of your comfort zone, learning from your experiences, and becoming a better version of yourself.

They were also influenced by their colleagues who had entered similar programs and longed for a cohort with which to collaborate in the learning. A veteran principal shared: “I had watched some of my friends go through it. It was a two-year program. It was a cohort. Once I started, I was with the same people for two years, which I loved. It was very hands-on, very collaborative.” A more novice principal also desired to become part of a cohort and learn from those with practical experience in the field, “I heard great things about it in terms of having a cohort and that many of the instructors were folks who were admins themselves or had been retired admins.” They felt that what they learned actually helped them be more effective teachers as this ELD TOSA explained: “I didn’t do it because I wanted to be an administrator. I did it because I wanted to learn how administrators think and work, so when I have to argue a point, I know where they are coming from.”I just realized that the impact that I could have in terms of setting up systems that were more equitable and having more interactions with families on a more authentic level [would be in leadership]. I love [my] community, and that’s why I want to work in partnership with our families to create more opportunities. It shouldn’t be where you’re born or who you’re born to that determines those opportunities that I was able to have, so we’re trying to open as many doors as we can here.

What They Hoped to Learn in Their Educational Leadership Preparation Program

However, they also realized that budgeting may be best learned on the job once one is in a leadership role. A district leader shared:Definitely school financing. As a teacher, I was always asking for supplies; I needed this and that. I really didn’t care where the budget came from. I just needed it. But that was really eye-opening, why the system has to be budgeted and why there are procedures in place and how many budgets a principal or director or school has to take into account.

Two participants were also interested in learning about different types of leadership roles such as those in district and county offices as an educational leadership student who took on a county level role shared here: “More about how the director roles play out at the district level. The flow of things from the state level to the county, from the county to the district.” Interestingly none of the 25 participants mentioned wanting to learn more about equity or serving multilingual learners in their educational leadership preparation program suggesting that it was not an expectation for them.I don’t know how any program can prepare you for that, quite frankly. Budgets are a big deal. Understanding this pot of money is called this, and it comes from the state like this, and this pot of money is called this, and it fluctuates from year to year based on this and this is federal money, and this is grant money. Just the ins and outs of the different kinds of money that come in and how it can be spent and how they’re connected and how they’re different.

3.2. What They Would Have Liked to Learn in Their Educational Leadership Preparation Program

A veteran director of a parochial school and former principal of a public school recognized that much of what is needed for a leadership role is learned through experience and that the cohort that she met through her educational leadership preparation program was the most valuable part of the experience:I was actually pleasantly surprised with the amount of stuff learned there that could apply to any leadership position in education. I felt like I could take what I learned and be a better teacher, activities’ director, or anything in the school system. It helped me understand budgets and Ed Code a little bit which was great, but really a lot of what was needed was, how do you coach someone? How do you look at data and find inequities? How do you understand the school system?

Similarly, the applied nature of the field experience part of educational leadership preparation programs was also seen to be helpful as described here by a novice assistant principal: “Anytime people ask me about the program, I say, I loved the field experience. Being able to sit and talk with the principal was so beneficial and necessary to learn admin duties.” However, a novice principal who did not have a positive experience in his educational leadership preparation program spoke of the need for a focus on practical skills and content like education law and budgeting as well because not everything can be learned through experience: “There’s a lot of technical pieces rather than the adaptive that I think are needed because you do learn it along the way, but sometimes I wish I would’ve known that at the beginning of the school year rather than the end of it.” He also did not have a cohort from his program to rely upon in these situations.It’s like being in the classroom. You take all those methods classes, but until you’re teaching, it doesn’t make sense to you. I think that it’s been really nice to have people that if I am faced with a problem and I don’t know how to handle it, I can go back and talk to them about it. I think that my program gave me a really good foundation, and knowing what questions to ask and when to ask them.

3.3. Course Requirements of Educational Leadership Preparation Programs

Focus on the Needs of Multilingual Learners

She also mentioned her work with the CalAPA; specifically, the second cycle focused on Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) and the third cycle focused on instructional coaching suggesting that the equity focus of the assessment may have influenced what is taught in these programs.There was definitely a lot of focus on that in terms of talking about them, making sure that they were at the forefront and how we are meeting their needs. Our schools have large populations of ELs and they’re underperforming so how do we bridge the gap? That was constantly a conversation. How are you including that in your vision, in your mission? How are you working with your teachers to meet those needs?

For those who did experience it, it was most apparent in their work with data analysis especially as part of the first cycle of the CalAPA. This was particularly true if they had chosen ELs as their focal group for one or more of the cycles as this novice assistant principal who attended a CSU shared: “Well, I feel like I spent a lot of time on it, but that was my focus [in the CalAPA]. I don’t know if that’s just me but maybe not as much in the coursework itself.” A Latine county level leader from a CSU program also spoke of the data piece when thinking about the needs of multilingual learners: “I feel like our program very much included ELs as well as students with disabilities in a lot of different case studies so that was very good to understand a lot of these other subgroups because they are all reported within the California Dashboard.” She went on to recount a meeting she attended as part of her current role in which she mentioned the Dashboard data and other county office employees were impressed that she was able to speak so fluently about the data.When I did the observations and also worked with my PLC, I had to lead the conversations and they were focused on how we are meeting the needs of students with disabilities, ELs and youth in transition so there was a focus on that. That was a positive for the program.

She felt that all teachers and educational leaders in the state should receive this training. Further, the skills she learned in the Bilingual Authorization also helped her to work more effectively to support speakers of languages other than Spanish as well as trilingual learners who are increasingly enrolling in her district’s schools.I realized my own biases and that I have a deficit mindset which comes from my own experience. Most of us in [the county] have that. [We say] ‘You need to learn English to go to work to be successful.’ We don’t value the first language. Most leaders have that mindset.

She has now started the first Spanish dual language program in the district in response to community demand.For 25 years, we’ve sacrificed one language to learn another. I think it’s a crime. As soon as they start school, they forget their Spanish. Kids cannot speak with their parents, so communication is lost. I can’t believe schools are letting that happen. There is no support for the native language. There is a big violence problem in [my district]. This year four parents died. A few years ago, middle school students were executed. They were 12. One dad said, ‘If my kid spoke Spanish he would be alive today.’ That’s so powerful and tragic at the same time. We stole the language from these kids. They’re alone.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The goal of the Migrant Education Program is to ensure that all migrant students reach challenging academic standards and graduate with a high school diploma (or complete a HSED) that prepares them for responsible citizenship, further learning, and productive employment (https://www.ed.gov/about/ed-offices/oese/office-of-migrant-education, accessed on 15 January 2025) (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.). |

| 2 | Bilingual Authorizations authorize the credential holder to provide instruction for English Language Development (ELD), primary language development, Specially Designed Academic Instruction Delivered in English (SDAIE), and content instruction delivered in the primary language (CTC, 2024c). |

References

- Acevedo, N., & Solorzano, D. G. (2021). An overview of community cultural wealth: Toward a protective factor against racism. Urban Education, 58(7), 1470–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartanen, B., & Grissom, J. A. (2021). School principal race, teacher racial diversity, and student achievement. Journal of Human Resources, 60(1), 666–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, A. J. (2023). From data management to actionable findings: A five-phase process of qualitative data analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, S. L. (2023). Examining the foundations of culturally and linguistically sustaining school leadership: Towards a democratic project of schooling in dual language bilingual education. Educational Administration Quarterly, 9(1), 72–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- California Department of Education [CDE]. (2022). English learners in California schools. Available online: https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/sg/englishlearner.asp (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Callahan, R., DeMatthews, D., & Reyes, P. (2019). The impact of Brown on EL students: Addressing linguistic and educational rights through school leadership practice and preparation. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 14(4), 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda v. Pickard, 648 F.2d 989. (1981). Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/~hakuta/www/LAU/IAPolicy/IA1bCastanedaFullText.htm (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Castillo, W., & Gillborn, D. (2023). How to “QuantCrit:” practices and questions for education data researchers and users. EdWorkingPaper: 22-546. Annenberg Institute at Brown University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, A., Coady, E., & Maranto, R. (2023). The roles of Black women principals: Evidence from two national surveys. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1138617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission on Teacher Credentialing [CTC]. (2016). About CalTPA. Available online: https://www.ctcexams.nesinc.com/PageView.aspx?f=GEN_AboutCalTPA.html (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Commission on Teacher Credentialing [CTC]. (2017). 2017 preliminary California administrative services credentialing content expectations and performance expectations with their alignment to the California professional standards for education administrators. Available online: https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/educator-prep/asc/2017-cape-and-cace.pdf?sfvrsn=f66757b1_2 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Commission on Teacher Credentialing [CTC]. (2024a). Administrative services credential for individuals prepared in California. Available online: https://www.ctc.ca.gov/credentials/leaflets/admin-services-credential-california-(cl-574c) (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Commission on Teacher Credentialing [CTC]. (2024b). Approved institutions and programs. Available online: https://www.ctc.ca.gov/commission/reports/data/approved-institutions-and-programs (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Commission on Teacher Credentialing [CTC]. (2024c). Other teaching supply: Bilingual authorizations. Available online: https://www.ctc.ca.gov/commission/reports/data/other-teacher-supply-bilingual-authorizations# (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- DeMatthews, D. E., & Izquierdo, E. (2018). Supporting Mexican American immigrant students on the border: A case study of culturally responsive leadership in a dual language elementary school. Urban Education, 55(30), 362–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ed Data. (2024a). Education data partnership—Monterey county. Available online: https://www.ed-data.org/county/Monterey (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Ed Data. (2024b). Education data partnership—Santa Cruz county. Available online: https://www.ed-data.org/county/Santa-Cruz (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Ed Trust. (2022). Educator diversity state profile: California. Available online: https://edtrust.org/rti/educator-diversity-state-profile-california/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- García, O., Alfaro, C., & Freire, J. (2024). Theoretical foundations of dual language-bilingual education. In J. Freire, C. Alfaro, & E. de Jong (Eds.), The handbook of dual language bilingual education (pp. 13–32). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gooden, M. A., Khalifa, M., Arnold, N. W., Brown, K. D., Meyers, C. V., & Welsh, R. O. (2023). A culturally responsive school leadership approach to developing equity-centered principals: Considerations for principal pipelines. The Wallace Foundation. Available online: https://wallacefoundation.org/report/culturally-responsive-school-leadership-approach-developing-equity-centered-principals (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. The Wallace Foundation. Available online: http://www.wallacefoundation.org/principalsynthesis (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Grooms, A. A., White, T., Peters, A. L., Childs, J., Farrell, C., Martinez, E., Resnick, A., Arce-Trigatti, P., & Duran, S. (2023). Equity as a crucial component of leadership preparation and practice. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 97(1), 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunting, K. (2021). Critical content analysis: A methodological proposal for the incorporation of numerical data into critical/cultural media studies. Annals of the International Communication Association, 45(1), 39–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Castillo, O. (2022). 3 ways to improve educational outcomes for English learners in P-12 schools. The Education Trust. Available online: https://edtrust.org/blog/3-ways-to-improve-educational-outcomes-for-english-learners-in-p-12-schools/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Kim, E. H. (2023). Motivations and Mechanisms: Stories of education leadership pathways. In J. Smith, & E. H. Kim (Eds.), Equity doesn’t just happen: Stories of education leaders working toward social justice (pp. 1–15). Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E. H., & Smith, J. (2024). “It makes me get up and want to work even harder”: Stories of education leadership pathways. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lac, V. T., & Diaz, C. (2023). Community-based educational leadership in principal preparation: A comparative case study of aspiring Latina leaders. Education & Urban Society, 55(6), 643–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563. (1974). Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/414/563/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- MacKinnon, K. H. (2024). Equity as a leadership competency: A model for action. Journal of School Leadership, 34(6), 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics [NCES]. (2022). English learners in public schools. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgf/english-learners (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- National Center for Education Statistics [NCES]. (2023a). Characteristics of public school teachers. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/clr (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- National Center for Education Statistics [NCES]. (2023b). The condition of education 2023: Chapter 2: Elementary and secondary enrollment. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/pdf/2023/cga_508.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Ni, Y., Rorrer, A. K., Xia, J., Pounder, D. G., & Young, M. D. (2022). Educational leadership preparation program features and graduates’ assessment of program quality. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 18(3), 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, G. P. (2023). English as a second or other language-focused leadership to support English language learners: A case study. Journal of Education, 203(3), 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodela, K., Rodriguez-Mojica, C., & Cochrun, A. (2021). ‘You guys are bilingual aren’t you?’ Latinx educational leadership pathways in the new Latinx diaspora. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 24(1), 84–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldana, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, M., & Lopez, F. (2015). Leadership for culturally and linguistically responsive schools. Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, D. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ understanding of culture in multicultural education: A qualitative content analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 110, 103580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, M., & Mendoza, C. (2021). Annual report on passing rates of commission-approved examinations from 2015–2016 to 2019–2020. Available online: https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/commission/agendas/2021-06/2021-06-4j.pdf?sfvrsn=3eca2ab1_2 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Theoharis, G. (2024). The school leaders our children deserve (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Office of migrant education. Available online: https://www.ed.gov/about/ed-offices/oese/office-of-migrant-education/ (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Wong, J. W., Athanases, S. Z., & Houk, J. (2024). From deficit to asset-based perspectives on multilingual learners: A critical inquiry in teacher education. The Teacher Educator, 60(2), 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Monterey | Santa Cruz | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Students | Teachers | Students | Teachers | |

| Latine | 79.4% | 23.4% | 55.7% | 13.5% |

| White | 12.6% | 61% | 35.7% | 78.6% |

| Black | 1.1% | 1.5% | 0.8% | 0.6% |

| Asian | 1.7% | 2.2% | 2% | 1.8% |

| ELs | 36.7% | * | 25.8% | * |

| Role | County | Gender | Race | EL | Multilingual | Years Experience | Admin Credential | Type of Institution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Principal | Monterey | Female | White | No | Yes | 25 | Yes | Private |

| Former Vice Principal | Monterey | Female | Latine | Yes | Yes | 11 | Yes | Public |

| Assistant Principal | Santa Cruz | Male | White | No | Yes | 8 | Yes | Public |

| Vice Principal | Monterey | Female | Latine | Yes | Yes | 11 | Yes | Public |

| Assistant Principal | Monterey | Female | White | No | No | 15 | Yes | COE |

| Vice Principal | Monterey | Male | Latine | Yes | Yes | 17 | Yes | Public |

| Assistant Principal | Monterey | Female | Latine | Yes | Yes | 20 | Yes | Public |

| Assistant Director | Monterey | Male | White | No | No | 20 | Yes | Public |

| Principal | Monterey | Male | White | No | No | 21 | Yes | COE |

| Department Chair | Santa Cruz | Female | White | No | No | 19 | Yes | Public |

| Induction Coach | Monterey | Female | White | No | No | 20 | No | |

| Assistant Principal | Monterey | Female | Mixed | No | Yes | 29 | Yes | Public |

| County Principal | Monterey | Female | White | No | No | 17 | Yes | Public |

| Principal | Monterey | Female | White | No | Yes | 25 | Yes | Public |

| Director | Monterey | Female | White | No | No | 20 | No | |

| ELD Coordinator | Monterey | Female | Latine | Yes | Yes | 32 | No | |

| Principal | Monterey | Male | Mixed | No | Yes | 24 | Yes | Private |

| Director/ELD Coordinator | Santa Cruz | Female | White | No | No | 20 | No | |

| Bilingual Community Liaison | Santa Cruz | Female | Latine | Yes | Yes | 2 | No | |

| Director- Curriculum and Instruction | Monterey | Female | White | No | Yes | 30 | Yes | Public |

| Principal | Monterey | Male | Mixed | No | No | 17 | Yes | Private |

| Assistant Director | Santa Cruz | Female | Latine | Yes | Yes | 11 | Yes | Public |

| Program Coordinator | Monterey | Female | Latine | Yes | Yes | 8 | Yes | Public |

| Assistant Director | Monterey | Female | White | No | Yes | 29 | Yes | COE |

| ELD TOSA | Monterey | Female | Latine | Yes | Yes | 24 | Yes | COE |

| Main Findings | Themes | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Motivation to enter an educational leadership preparation program |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| What they hoped to learn in their educational leadership preparation program |

|

|

| What they would have liked to learn in their educational leadership preparation program |

|

|

| Course requirements of educational leadership preparation programs |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, E.; Ishimaru, K.L. Centering Identity and Multilingualism in Educational Leadership Preparation Programs. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111435

Kim E, Ishimaru KL. Centering Identity and Multilingualism in Educational Leadership Preparation Programs. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111435

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Elisabeth, and Kalah Larison Ishimaru. 2025. "Centering Identity and Multilingualism in Educational Leadership Preparation Programs" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111435

APA StyleKim, E., & Ishimaru, K. L. (2025). Centering Identity and Multilingualism in Educational Leadership Preparation Programs. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111435