1. Introduction

In recent years, the discourse surrounding curriculum reform has shifted toward more inclusive and culturally responsive paradigms (

Luckett & Shay, 2020). This global trend underscores the importance of contextualizing educational content by incorporating local knowledge systems, Indigenous epistemologies, and sociocultural realities into formal curricula, particularly in developing nations of the Global South (

Ajani, 2025). The homogenizing tendencies of standardized education, often inherited from colonial structures, have led to a growing recognition of the limitations inherent in universalist models that overlook the value of local perspectives, community practices, and cultural heritage (

Amin, 2024). Consequently, integrating local knowledge into curriculum design has emerged as a strategic imperative in creating more equitable, relevant, and transformative educational systems.

In Indonesia, this imperative is reflected in the government’s national policy reform, known as

Merdeka Belajar (Freedom to Learn), which was launched by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology in 2019. The policy envisions a decentralization of curricular authority, enabling schools and higher education institutions to tailor learning content to regional, cultural, and institutional contexts (

Tobondo, 2024). One of its key aspirations is to foster student agency, interdisciplinary learning, and the revitalization of local content within academic structures (

Tangwe & Benyin, 2025). Rather than treating local knowledge as ancillary or extracurricular,

Merdeka Belajar encourages its integration as a core dimension of pedagogy and curriculum innovation, thereby challenging the dominance of nationally standardized and globally homogenized educational frameworks.

Aceh, located on the northwestern tip of Sumatra, provides a unique sociocultural and political landscape for examining such curricular transformations. As a region with special autonomy status following the 2005 Helsinki Peace Agreement, Aceh maintains a distinct identity shaped by Islamic jurisprudence (

qanun), a history of protracted conflict, and strong communal traditions rooted in customary law (

adat). These characteristics position Aceh not only as a symbol of local resilience and cultural pride but also as a strategic site for implementing context-sensitive curriculum reforms that reflect local wisdom, belief systems, and community values (

Abubakar et al., 2022). While primary and secondary education in Aceh has seen efforts to integrate local content, such as folklore, traditional law, and historical narratives, there remains a paucity of empirical studies examining how local knowledge is operationalized within the context of higher education curriculum reform.

This study addresses that gap by focusing on curriculum innovation within universities and higher education institutions in Aceh. Despite national encouragement through the

Merdeka Belajar policy, higher education institutions face multifaceted challenges in embedding local knowledge into teaching and learning processes. These include institutional inertia, accreditation rigidities, a lack of pedagogical training in culturally responsive approaches, and tensions between universal academic standards and regional particularities (

Joshi, 2024). Given the tension between policy aspirations and institutional realities, it is crucial to examine how educators and curriculum developers in Aceh interpret, adapt, and apply local knowledge in their academic practices.

Table 1 presents the alignment between the research questions, hypotheses, impact indicators, and the methods for empirical validation employed in this study. While the dominant approach is qualitative, the formulation of hypotheses provides a structured lens to guide data interpretation and strengthen the analytical rigor. Each research question is linked to a theoretically grounded hypothesis, drawing primarily on Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (

Ladson-Billings, 2021) and Curriculum Contextualization Theory (

Ramírez, 2020).

The “Impact Indicators” column specifies measurable parameters such as the level of lecturers’ cultural awareness, the extent of local values embedded in curriculum documents, and institutional support structures that allow for partial empirical validation even within a qualitative framework. The “Methods for Empirical Validation” column demonstrates how these indicators are operationalized through a combination of qualitative techniques (e.g., thematic analysis of interviews and FGDs, classroom observations, policy document analysis) and limited quantitative measures (e.g., frequency counts, descriptive statistics).

This integration of qualitative depth with selective quantitative cross-checks enhances the validity and credibility of the findings, addressing potential concerns about subjectivity and providing a clearer empirical basis for interpreting the impact of local knowledge integration. By explicitly linking each element to theoretical frameworks and operational indicators, the table ensures methodological transparency and strengthens the connection between the conceptual foundation and this study’s practical outcomes.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definitions and Frameworks of Local Knowledge in Education

Local knowledge, also referred to as Indigenous knowledge, traditional knowledge, or community wisdom, has been conceptualized as the accumulated cultural, ecological, spiritual, and practical understandings specific to a particular geographic and sociocultural context (

Brondízio et al., 2021). In education, local knowledge is not merely content to be taught; it constitutes a framework of knowing and being that challenges dominant epistemologies, especially those derived from Eurocentric models (

Zidny et al., 2020). The incorporation of local knowledge into curricula is viewed as a means to promote cultural identity, linguistic preservation, and context-based problem-solving skills among learners (

Assefa & Mohammed, 2022).

Pedagogically, integrating local knowledge aligns with constructivist learning theory, which posits that students build meaning through their interactions with the world around them (

Al Abri et al., 2024). Scholars have argued that when learners encounter content that reflects their lived experiences, learning becomes more meaningful, transformative, and empowering (

Al-Husban & Al’Abri, 2024). This integration also contributes to the development of what UNESCO terms “culturally sustaining education,” wherein schools serve as platforms for the continued vitality of local traditions and values (

Mould, 2022).

Local knowledge in education refers to the integration of community-specific wisdom, practices, and cultural heritage into teaching and learning processes. It operates both as a source of educational content and as an epistemological framework that informs pedagogy. Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and the Decolonization of the Curriculum provide theoretical lenses for understanding how local knowledge can reshape the purpose, methods, and outcomes of higher education (

Shahjahan et al., 2022). This approach moves beyond the mere inclusion of cultural elements to addressing the hidden curriculum, which carries implicit values, social assumptions, and behavioral norms.

2.2. Global and Regional Models of Curriculum Contextualization

Efforts to contextualize the curriculum have been undertaken across multiple regions, particularly in postcolonial and multilingual societies. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, countries such as Kenya and Ghana have sought to incorporate Indigenous ecological knowledge into science and environmental education (

Chimbutane, 2023). Similarly, in the Pacific Islands, curriculum reform has emphasized storytelling, communal practices, and traditional ecological management as valid sources of knowledge (

Nunn et al., 2024).

In Southeast Asia, the regional discourse around curriculum contextualization is gaining traction. Malaysia has developed “cultural modules” integrated into school curricula that reflect ethnic diversity and traditional values. The Philippines has also undertaken efforts to incorporate ethnolinguistic knowledge through its

Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education (MTB-MLE) program, reinforcing community identity while enhancing academic outcomes (

Escarda et al., 2024). These models underscore a global consensus that curricular relevance is key to educational quality and equity, particularly in multicultural societies.

In recent decades, higher education systems worldwide have increasingly adopted culturally responsive and inclusive approaches to curriculum design, recognizing the integration of local knowledge as a key driver of educational relevance and innovation. In Europe, for example, Norway has embedded Sámi Indigenous knowledge into teacher education programs, not only to preserve linguistic and cultural heritage but also to promote intercultural competence among students from diverse backgrounds (

Spieler et al., 2025). Similarly, Latvia and Lithuania have systematically incorporated regional history, folklore, and traditional ecological knowledge into higher education curricula as part of national strategies to strengthen the cultural identity within the framework of academic globalization (

Kremer, 2016). These initiatives demonstrate that valuing local heritage as a source of epistemological diversity rather than treating it as a peripheral supplement can coexist with the demands of international accreditation and employability frameworks. Through flexible curriculum policies, universities in these contexts have successfully fostered student engagement, cultivated cultural pride, and achieved global learning outcomes.

Comparable trends are evident in other regions. In Asia, it was found that embedding local perspectives into Chinese university curricula enhances student engagement and reinforces cultural identity (

Peng & Abd Rahman, 2024). In Africa, it is emphasized that local knowledge serves not only as content but also as an epistemological framework capable of challenging the dominance of Western paradigms in higher education (

Kaya & Seleti, 2013). In Latin America, the concept of

epistemologies of the South calls for the reclamation of community-based knowledge as a foundation for educational innovation. These global experiences affirm that integrating local knowledge is not a uniform process; instead, it must be adapted to the unique social, political, and cultural conditions of each context (

Santos, 2018).

Methodological approaches such as participatory curriculum designs and community-based learning further highlight the importance of active stakeholder engagement, particularly from local communities, educators, and policymakers, in ensuring the sustainability and authenticity of curriculum contextualization (

Sai’in et al., 2024). For Aceh, these comparative insights offer concrete pathways for balancing cultural preservation with global competitiveness. Mechanisms such as mandatory cultural studies modules, community-based research projects, and language preservation initiatives could be strategically aligned with both national higher education objectives and international quality assurance standards. Ultimately, the success of such integration depends on coherent policy support, institutional commitment, and collaborative partnerships that position local knowledge as both academically rigorous and culturally authentic.

2.3. Studies on Merdeka Belajar and Cultural Responsiveness

Indonesia’s

Merdeka Belajar policy represents a shift toward educational democratization, granting autonomy to teachers and institutions to design context-specific curricula tailored to their needs. The framework emphasizes student-centered learning, interdisciplinary approaches, and the integration of local content as part of national learning outcomes (

Putri, 2021). Within this policy, the concept of

Profil Pelajar Pancasila advocates for six core student attributes, including cultural identity, creativity, and critical thinking elements, which are closely aligned with the goals of culturally responsive education (

Suratmi & Hartono, 2024).

Several studies have examined the impact of

Merdeka Belajar in primary and secondary education. For example, the research found that the policy encourages innovative pedagogies, yet its implementation often lacks alignment with teacher competencies and institutional readiness (

Kuznetsova et al., 2024). The other researchers noted that, while there is a rhetorical emphasis on local content, many higher education institutions still rely on nationally standardized materials that marginalize regional diversity (

Pineda & Mishra, 2023). These findings suggest that without systemic support and conceptual clarity, the policy’s cultural responsiveness goals may remain aspirational rather than transformative.

The

Merdeka Belajar policy in Indonesia emphasizes flexibility, creativity, and contextualization in education, making it an enabling framework for integrating local knowledge into higher education curricula. Previous studies have examined how culturally responsive approaches under

Merdeka Belajar can promote student identity formation, critical thinking, and social responsibility (

Fatmawaty et al., 2024). However, gaps remain in linking these national policies with global theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence from diverse regions.

2.4. Challenges in Curriculum Reform in Developing Nations

Curriculum reform efforts in developing nations frequently encounter a complex array of challenges. Institutional inertia, rigid accreditation frameworks, and limited professional development opportunities are among the most persistent barriers (

Al-Worafi, 2024). Additionally, tension exists between national education policies, which often prioritize international competitiveness, and local demands for relevance and equity (

Puad & Ashton, 2023). This dichotomy leads to what scholars term the “curriculum dilemma,” where educators must navigate between global benchmarks and the cultural realities of their students (

Fitzgerald et al., 2023).

In contexts like Indonesia, particularly in peripheral regions such as Aceh, logistical issues such as infrastructure, political decentralization, and socio-religious considerations further complicate curriculum innovation. The integration of local knowledge is often hampered by insufficient research on Indigenous pedagogies, a lack of institutional commitment, and the undervaluing of non-Western knowledge systems in academic settings (

Silvestru, 2023). These structural and epistemic challenges necessitate a rethinking of how curriculum development is approached, especially in higher education settings tasked with cultivating both academic excellence and cultural integrity.

Curriculum reform in developing nations often faces structural, institutional, and capacity-related challenges. These include limited lecturer competencies in implementing contextualized curricula, tensions between local and international academic standards, and insufficient quality assurance mechanisms despite regular accreditation processes (

Makhoul, 2019). Furthermore, balancing cultural preservation with the adoption of global competencies presents a persistent dilemma for policymakers and educators. Addressing these challenges requires a nuanced approach that considers both the sociocultural foundations and the international competitiveness of higher education programs.

3. Theoretical Framework

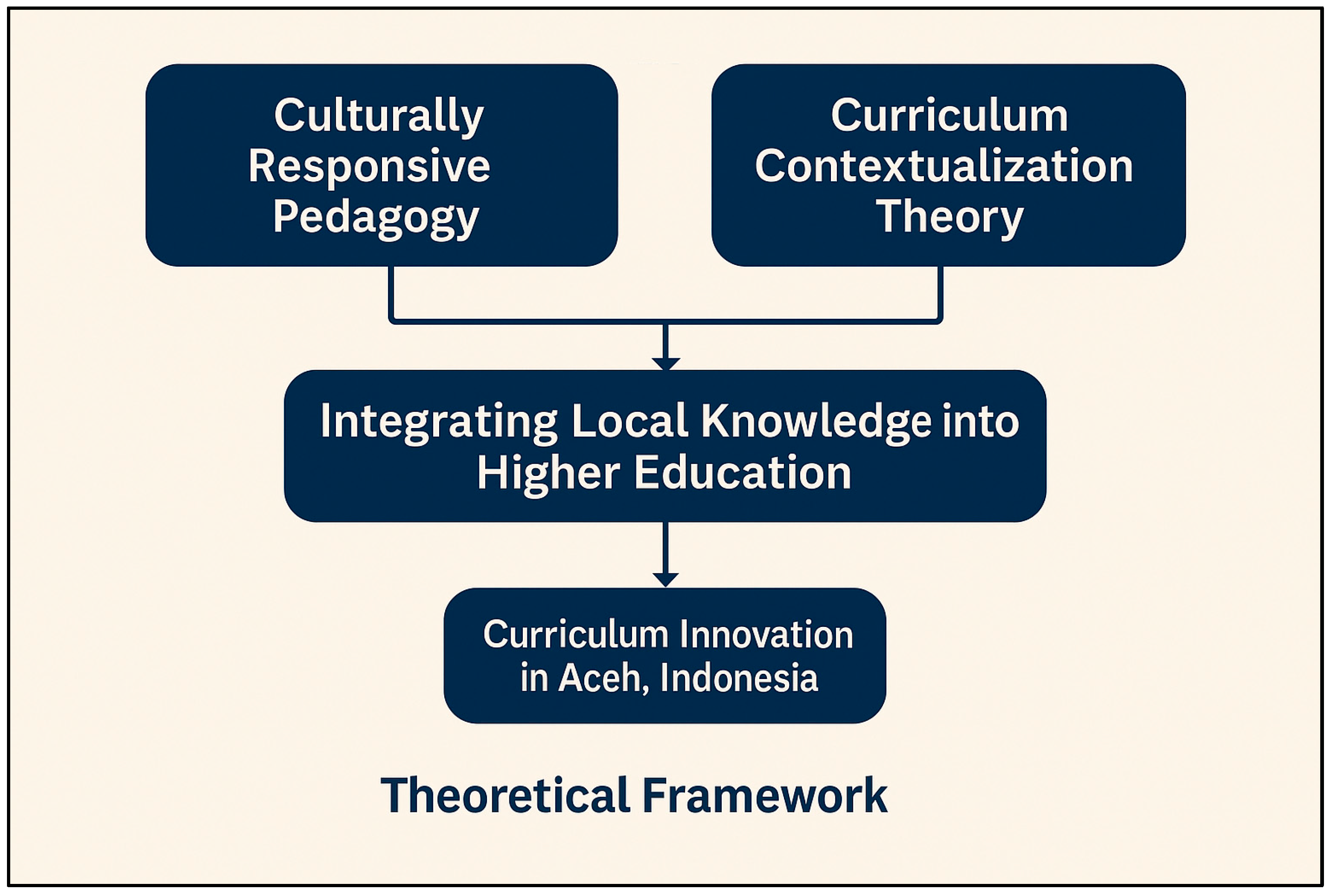

This study is grounded in two complementary theoretical frameworks: Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) and Curriculum Contextualization Theory. Together, these frameworks provide a conceptual foundation for understanding how local knowledge can be meaningfully integrated into higher education curricula, particularly within the unique sociocultural and political context of Aceh.

3.1. Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP)

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP), as articulated by

Gay (

2018), emphasizes the need for educators to incorporate students’ cultural backgrounds, languages, and lived experiences into teaching and learning processes (

Chang & Viesca, 2022). CRP posits that education should not be culturally neutral; instead, it must actively engage with and validate the cultural assets of learners to enhance academic success and identity development (

Wahed & Pitterson, 2023). Within this framework, the inclusion of local knowledge is not merely additive but transformative. It reshapes the curriculum, pedagogy, and teacher–student relationships to reflect the sociocultural realities of the community.

CRP aligns with the goals of the

Merdeka Belajar policy, which encourages localized curriculum design and student-centered learning approaches. In higher education, this requires lecturers and curriculum developers to engage in critical reflection about whose knowledge is privileged, how cultural knowledge is positioned in the curriculum, and what pedagogical strategies are appropriate in specific contexts (

Rumondor, 2024).

The integration of local knowledge into higher education can be grounded in Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP)

, a concept pioneered by

Ladson-Billings (

1995,

2022) CRP emphasizes that effective teaching must recognize, value, and leverage students’ cultural identities as integral assets in the learning process (

Fitch, 2024). It fosters three interrelated goals: academic success, cultural competence, and critical consciousness. In the context of higher education in Aceh, CRP offers a robust framework for ensuring that the curriculum design reflects students’ lived experiences, linguistic resources, and sociocultural realities, thereby enhancing both engagement and learning outcomes.

Complementing CRP, Curriculum Contextualization Theory

Bernstein (

2000);

Holliday (

2010) posits that educational content should be adapted to the sociocultural context of learners without compromising the integrity of the core disciplinary knowledge (

Vitale & Exley, 2015). This theory supports the strategic alignment of local knowledge such as Acehnese

adat (customary law), oral traditions, and ecological wisdom with national higher education standards and global competencies. By situating learning within culturally meaningful contexts, curriculum contextualization enhances relevance, affirms identity, and bridges the gap between academic knowledge and community needs.

The work of other influential scholars further expands the CRP discourse by emphasizing the central role of educator preparation and intercultural pedagogy (

Chang & Viesca, 2022). Their perspectives highlight that the successful integration of local knowledge requires not only policy-level commitment but also sustained capacity-building for lecturers. For Aceh, this means equipping faculty with the pedagogical skills needed to design culturally contextualized learning experiences while meeting rigorous national and international quality assurance standards.

Bringing CRP and Curriculum Contextualization Theory together in Aceh’s higher education reform agenda offers a dual advantage: it affirms local identity through culturally grounded teaching while preparing students with the analytical, communicative, and intercultural competencies necessary for global citizenship. This theoretical synergy aligns with international trends in inclusive education and provides a coherent foundation for policies and practices that can thrive in culturally diverse academic settings.

3.2. Curriculum Contextualization Theory

Curriculum Contextualization Theory draws on the curriculum studies literature, which challenges universalist models of education. This theory asserts that the curriculum content, structure, and delivery must be adapted to reflect the unique cultural, historical, and geographic context in which it operates (

Ngoasong, 2022). Contextualization involves aligning educational experiences with the local sociocultural context to enhance learner relevance, motivation, and critical engagement.

In the case of Aceh, curriculum contextualization implies embedding regional values, Islamic perspectives, local wisdom (

kearifan lokal), and traditional ecological knowledge into the learning process. The theory encourages participatory curriculum development that involves local stakeholders, including educators, cultural leaders, and community members, to co-construct knowledge that is both academically rigorous and culturally grounded (

Fernández-Villarán et al., 2024). This theoretical orientation is particularly relevant in post-conflict regions, where rebuilding educational identity is closely tied to cultural restoration and social reconciliation. It also serves as a response to critiques of the dominance of globalized Western knowledge systems in higher education, offering a pathway for decolonizing the curriculum and restoring epistemic sovereignty in marginalized regions.

The concept of curriculum decolonization underscores the need to dismantle and challenge knowledge structures shaped by colonialism and the dominance of Western epistemologies (

Shahjahan et al., 2022). Within this framework, local knowledge is not merely an add-on but is positioned at the core of reconstructing a fair and inclusive curriculum. Decolonization focuses not only on

what is taught but also on

how and

why knowledge is taught, including the

hidden curriculum that conveys implicit values, norms, and cultural assumptions (

Mayo, 2024). In practice, this involves deconstructing the hierarchy of knowledge that privileges international curricula as the sole standard, replacing it with an approach that values epistemological pluralism. By combining CRP and the decolonization framework, this study analyzes how a local knowledge-based curriculum in Aceh can be integrated into a higher education system that has traditionally adhered to national and international standards. This theoretical lens enables the identification of both potential synergies and tensions between local values and global knowledge canons, and it opens space for constructive compromise strategies.

3.3. Intersection of CRP and Contextualization in This Study

By combining Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and Curriculum Contextualization Theory, this study situates the integration of local knowledge as both a pedagogical necessity and a curricular imperative (

Nataño, 2023). This dual perspective enables this research to examine not only how local knowledge is incorporated (content-wise) but also how it is implemented (pedagogically and institutionally) within the framework of

Merdeka Belajar. These theories inform the design of the research instruments, guide the interpretation of data, and provide the basis for deriving practical recommendations for inclusive, context-sensitive curriculum reform in Aceh and similar cultural settings.

Figure 1 presents the theoretical framework underpinning this study. The integration of local knowledge into higher education is informed by two foundational theories: Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) and Curriculum Contextualization Theory. CRP emphasizes the need for a pedagogy that acknowledges and validates students’ diverse cultural backgrounds, thereby fostering their identity, motivation, and engagement in the learning process (

Gay, 2018) is approach ensures that local values and Indigenous epistemologies are not peripheral but central to educational designs. Meanwhile, Curriculum Contextualization Theory supports the adaptation of the curriculum content, structure, and delivery to align with the sociocultural, historical, and regional realities of learners (

Joshi, 2024). When applied together, these theories provide a synergistic foundation for embedding local knowledge as both the content and process in higher education reform. The integration of these two perspectives enables a transformative approach to curriculum development, particularly in Aceh, a region with distinct religious, historical, and cultural characteristics. Ultimately, this theoretical synthesis leads to curriculum innovation as institutions respond to the

Merdeka Belajar policy by developing localized and culturally relevant academic programs.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Research Design

A qualitative case study approach was employed to examine the integration of local knowledge into higher education curricula within the context of Aceh, Indonesia. This design was chosen for its capacity to provide an in-depth understanding of complex educational phenomena in real-life settings (

Amiruddin et al., 2024). This study aimed to capture the processes, perceptions, and meanings attached by lecturers, students, and stakeholders to curriculum innovation under the

Merdeka Belajar policy. The predominance of a qualitative approach enabled the exploration of intricate sociocultural contexts, actor interactions, and institutional dynamics that cannot be adequately represented through quantitative surveys alone. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions (FGDs), and in-depth interviews, generating rich narrative evidence essential for developing a contextually relevant conceptual framework and actionable recommendations.

4.2. Research Site and Participants

This study was conducted across several higher education institutions in Aceh Province, a region known for its unique sociocultural and political context. A total of 100 participants were selected using purposive sampling to ensure representation from key stakeholder groups. These participants included 60 university lecturers from various academic departments, 25 curriculum developers and academic coordinators, and 15 policymakers involved in educational planning and curriculum oversight (

Table 2). All participants were selected based on their experience, institutional roles, and direct involvement in curriculum design and implementation.

4.3. Data Collection

Data were gathered through semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) conducted between January and March 2025. A total of 60 in-depth interviews were conducted, each lasting approximately 45 to 60 min. Additionally, eight focus group discussions were conducted, with 5 to 8 participants in each group. The interviews and FGDs were conducted in Bahasa, Indonesia, audio-recorded with the participants’ consent, and later transcribed verbatim. All data collection procedures were conducted following research ethics and confidentiality protocols approved by the institutional ethics committee.

4.4. Data Analysis

The collected data were analyzed using thematic analysis, following the six-phase model (

Peel, 2020). In the initial phase, transcripts were read repeatedly to gain familiarity with the content. Codes were then generated systematically across the dataset. The resulting codes were organized into potential themes, which were reviewed, refined, and clearly defined. To facilitate coding and theme development, NVivo 12 software was utilized. To ensure the credibility and trustworthiness of findings, triangulation, member checking, and peer debriefing techniques were applied. Final themes were determined through iterative discussions among the research team.

To provide a clear context for the institutional scope of this study,

Table 2 lists the higher education institutions in Aceh that participated in the research. The inclusion of these universities serves two purposes: first, to illustrate the diversity of institutional types ranging from public universities to Islamic higher education institutions that are actively involved in integrating local knowledge into their curricula; and second, to highlight the range of academic environments in which this study’s findings were generated. The table also indicates the number of respondents from each university, including lecturers, curriculum developers, and policymakers, who contributed to the qualitative data through interviews and focus group discussions. Presenting this information not only clarifies the geographic and institutional representation of this study but also strengthens the validity of the findings by showing the breadth of perspectives collected across multiple higher education contexts in Aceh.

5. Results

This section presents this study’s findings, derived from in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with 100 participants, including lecturers, curriculum developers, and policymakers from various higher education institutions across Aceh, Indonesia. Thematic analysis was used to organize and interpret the qualitative data, revealing key patterns and perspectives related to the integration of local knowledge into curriculum innovation within the framework of the Merdeka Belajar policy. The results are structured around four major themes that emerged during the analysis: 1. Perceptions of Local Knowledge in Higher Education, 2. Strategies and Practices for Curriculum Integration, 3. Institutional and Systemic Challenges, and 4. Enabling Factors and Opportunities for Innovation. These themes reflect not only the participants’ lived experiences and institutional realities but also illustrate broader sociocultural dynamics influencing educational reform in Aceh. Excerpts from participant narratives are included to support the analysis and enhance the credibility of the findings. A deeper interpretation follows the presentation of results in the Discussion Section, where connections are drawn between the findings and the theoretical framework, as well as the existing literature.

5.1. Demographic Profile of Participants

Table 3 presents the demographic profile of 100 participants involved in this study, comprising university lecturers (60%), curriculum developers (25%), and education policymakers (15%) across higher education institutions in Aceh. A majority (75%) were affiliated with state universities, while the remaining 25% came from private institutions. Geographically, 65% were based in urban areas and 35% in rural or regional locations, allowing for contextual representation. Among the lecturers, 40% had over 10 years of teaching experience, 40% had 6–10 years, and 20% had 1–5 years. Participants also came from diverse academic backgrounds, including Education and Social Sciences (38%), Islamic Studies (22%), Engineering and Technology (20%), and Science and Health (20%). This demographic diversity enriched this study’s exploration of how local knowledge is integrated into higher education curricula under the

Merdeka Belajar policy.

5.2. Validity and Reliability of Research Data

Table 4 summarizes the strategies used to ensure the validity and reliability of the qualitative data in this study. To establish credibility, triangulation across participant groups, member checking, and prolonged engagement were applied to verify the accuracy and depth of findings. Transferability was addressed through rich contextual descriptions, enabling readers to assess the applicability of results to similar settings. Dependability was maintained by documenting a transparent audit trail and conducting peer debriefings to ensure consistency in the coding and interpretation. Finally, confirmability was reinforced through reflexive journaling and the use of the NVivo 12 software, which supported systematic data management and analytical traceability. These strategies collectively ensured the trustworthiness of this study, adhering to the qualitative rigor framework outlined by (

Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

5.3. Theme Findings of Research

5.3.1. Perceptions of Local Knowledge in the Curriculum

The perception of local knowledge (kearifan lokal) among participants was predominantly positive, with respondents recognizing its critical role in shaping a culturally responsive and contextually grounded higher education curriculum. The integration of local wisdom was widely viewed as a means to support character development, enhance cultural relevance, and align with the national vision of the Profil Pelajar Pancasila, as emphasized in Indonesia’s Merdeka Belajar policy. Several lecturers and curriculum developers described the process as an effort to “membumikan ilmu” literally “grounding knowledge” to make academic learning more meaningful and reflective of students’ lived experiences.

However, respondents also identified persistent barriers. A recurring concern was the academic marginalization of local knowledge, particularly in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) faculties, where such content is often viewed as lacking in scientific rigor or institutional relevance. This tension between the universalism of formal academic standards and the contextualism of local knowledge was frequently cited as a core challenge in achieving broader curricular acceptance.

Despite these obstacles, examples of innovation and promising practices emerged. Some institutions had institutionalized local knowledge through elective courses, while others had founded research centers dedicated to local culture and Indigenous studies. Collaborative curriculum development involving community leaders, religious scholars, and cultural practitioners was also reported as an effective strategy for enhancing legitimacy and implementation. Particularly noteworthy were multidisciplinary models that integrated local wisdom with scientific knowledge, such as in agroecology and disaster risk education, which were seen to enhance relevance and engagement.n our education faculty, we developed a learning model where students co-teach in

pesantren using local proverbs to explain abstract concepts. It bridges language and logic beautifully.” (Lecturer, Universitas Syiah Kuala). This reflects how culturally rooted teaching methods can enhance understanding. Despite systemic barriers in recognition and institutional support, efforts to legitimize and innovate through local content are gaining momentum in Aceh’s higher education (

Table 5).

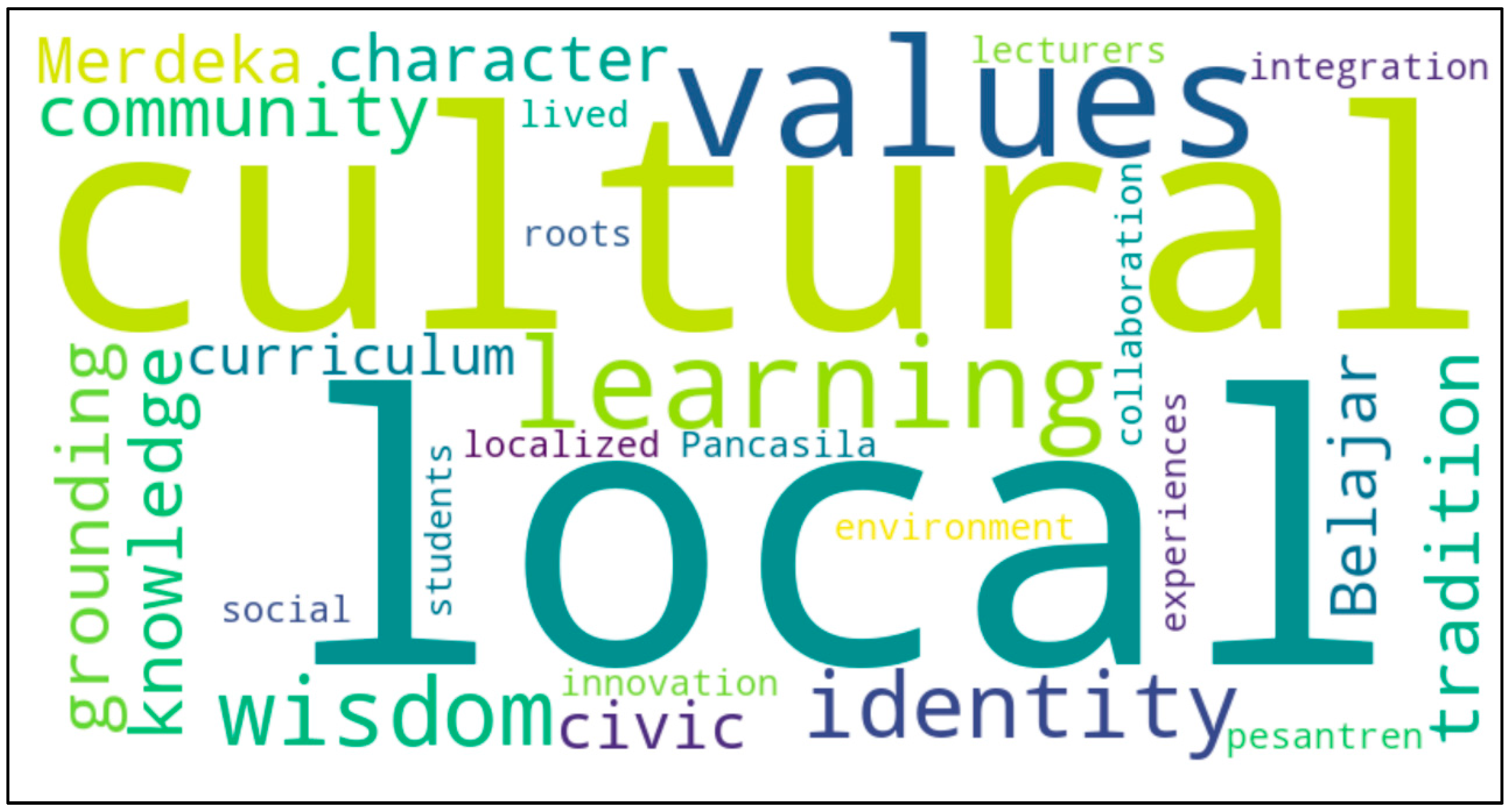

Figure 2 presents a word cloud depicting prominent thematic keywords derived from the qualitative data. The visualization illustrates the lexical emphasis placed by participants on core concepts, including “local wisdom,” “cultural identity,” “tradition,” “community,” and “curriculum integration.” These terms reflect recurring values and themes associated with efforts to contextualize education by incorporating local knowledge. Notably, terms like “grounding knowledge,” “civic values,” and “lived experiences” indicate the pedagogical and philosophical orientations embedded in the discourse. The presence of policy-linked keywords, such as Merdeka Belajar and Pancasila, reinforces the participants’ alignment with national educational reforms. At the same time, terms like

innovation,

collaboration, and

pesantren emphasize the varied strategies and cultural foundations shaping curriculum design. This word cloud serves as a visual summary of how local knowledge is conceptualized and articulated across roles, providing insight into the epistemological and practical dimensions of the curriculum transformation in post-pandemic Indonesian higher education.

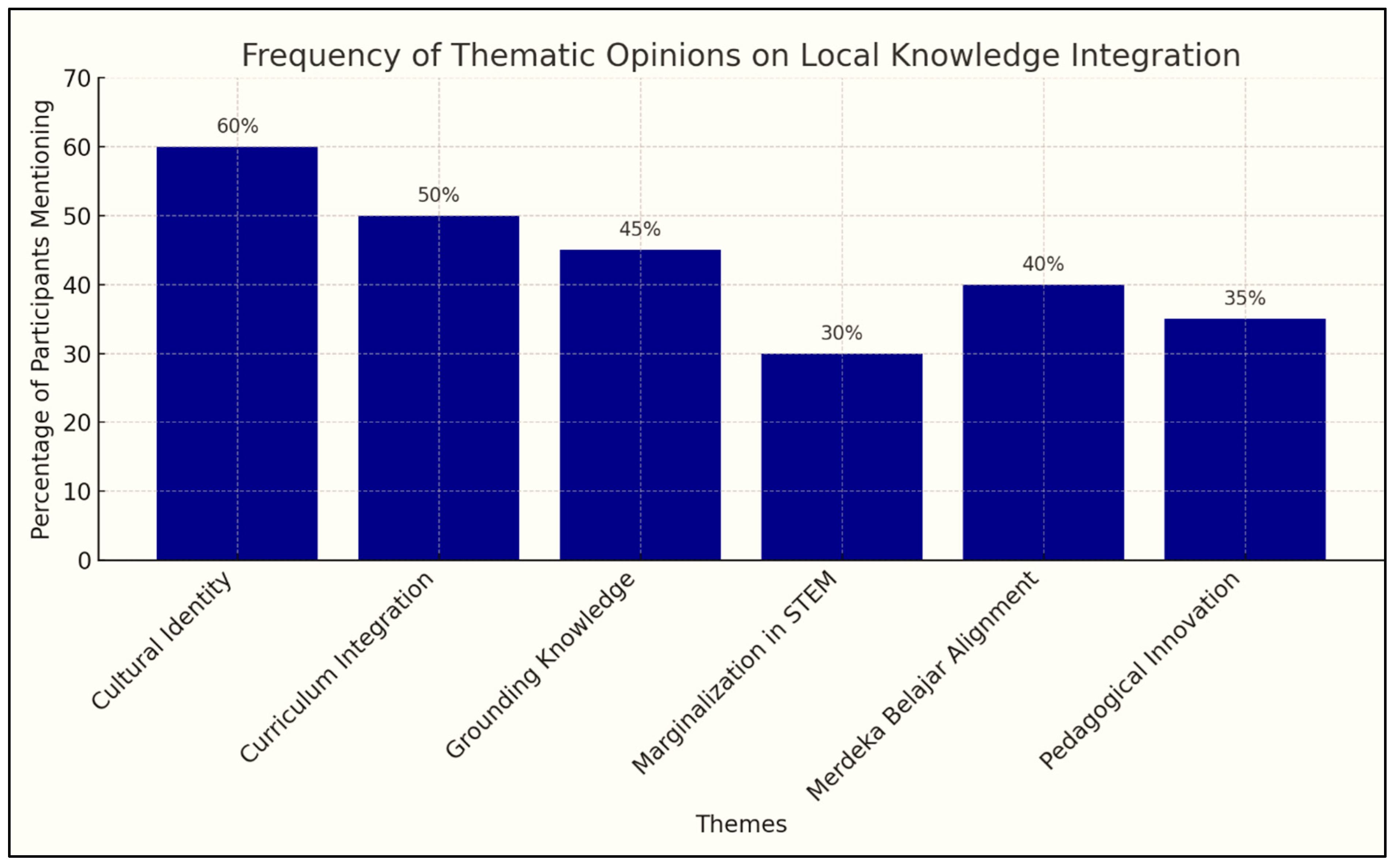

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of thematic opinions expressed by participants concerning the incorporation of local knowledge into higher education curricula. The most frequently mentioned theme was cultural identity (60%), underscoring the perception that integrating local knowledge serves as a key mechanism for strengthening students’ awareness of their heritage and societal roles. This aligns closely with the national agenda of

Profil Pelajar Pancasila. Curriculum integration (50%) and grounding knowledge in local realities (45%) were also widely cited, reflecting pedagogical concerns regarding how to embed local content in meaningful and context-sensitive ways. Meanwhile, the alignment with Merdeka Belajar (40%) indicated institutional efforts to contextualize national policies with regional cultural practices. Conversely, marginalization in STEM disciplines (30%) emerged as a notable barrier, highlighting ongoing skepticism about the academic legitimacy of local knowledge, especially in technical fields. Pedagogical innovation (35%) was viewed as a strategic opportunity to bridge global competencies with local insights, particularly through interdisciplinary teaching and community-based projects. The distribution of responses reveals both strong support for the relevance of local knowledge and the recognition of structural and epistemological challenges in realizing its full curricular potential.

5.3.2. Methods of Integration: Themes, Community-Based Learning, and Assessment

Participants described a variety of pedagogical and institutional strategies for embedding local knowledge into higher education curricula. A widely recognized approach was the thematic embedding of culturally rooted content such as Acehnese history, adat (customary law), traditional ecological knowledge, and oral literature—into course syllabi. This strategy was particularly prevalent in faculties of the humanities, education, and social sciences, where lecturers adapted teaching materials and classroom discussions to reflect local realities and cultural heritage better. Another prominent method was the implementation of community-based learning, notably through programs like Kuliah Kerja Nyata (KKN) and other forms of service-learning. These initiatives enabled students to engage directly with local communities, co-producing knowledge through collaborative research, documentation, and social projects. Such field-based learning experiences were seen as vital in bridging theoretical instruction with the lived experiences and wisdom of Indigenous communities. As one curriculum developer from the Universitas Teuku Umar noted: “Our curriculum includes modules where students work with coastal communities to document traditional fishing techniques, which they later analyze through sustainability frameworks.”

Assessment methods were also adapted to capture student engagement with local knowledge. Project-based evaluations, reflective journals, and participatory community mapping were commonly employed. These approaches encouraged students to critically analyze their field experiences, propose innovative solutions grounded in local contexts, and reflect on the cultural and environmental dimensions of their learning. In particular, participatory mapping stood out as both pedagogically enriching and socially empowering. Students worked alongside community members to document local spatial knowledge—such as traditional fishing zones, sacred spaces, and historical landscapes—thereby validating Indigenous perspectives while contributing to community development goals. Collectively, these methods reflect a pedagogical shift toward experiential, reflective, and collaborative learning, which aligns with the core principles of Indonesia’s Merdeka Belajar policy. They also signify an institutional commitment to culturally responsive education that is grounded in local wisdom, socially relevant, and capable of fostering interdisciplinary thinking.

Table 6 summarizes the primary strategies employed by higher education institutions in Aceh to integrate local knowledge into the curriculum. The most common approach involved thematic embedding, whereby the course content was aligned with local contexts such as Acehnese culture,

adat traditions, and ecological practices. This approach enabled instructors to contextualize academic knowledge and enhance student engagement by incorporating relevant sociocultural narratives. Community-based learning was also a prominent model, particularly through

Kuliah Kerja Nyata (KKN) or similar service-learning programs. These initiatives enabled students to collaborate directly with residents, facilitating two-way knowledge exchange and fostering social responsibility. In terms of assessment, project-based evaluations and reflective journaling were favored for their ability to capture both analytical and experiential dimensions of student learning. These tools not only assessed academic performance but also documented the development of civic values and critical awareness. Ultimately, participatory community mapping emerged as an inclusive and transformative practice that validated Indigenous spatial knowledge while enhancing the student understanding of local development dynamics. Collectively, these methods demonstrate a holistic, student-centered, and culturally responsive approach to curriculum innovation, aligning with the

Merdeka Belajar framework.

5.3.3. Institutional and Policy-Related Challenges

Key challenges included the absence of institutional guidelines, limited lecturer capacity, and pressure to align with national accreditation standards that emphasize universal and standardized competencies. Respondents reported a lack of administrative support, insufficient training in Culturally Responsive Pedagogy, and tensions between the need for curriculum flexibility and bureaucratic accountability. “We are encouraged to localize our content, but the accreditation system still uses national rubrics with no indicators for local integration.” (Academic Coordinator, Universitas Malikussaleh).

Table 7 synthesizes the key institutional and policy-related challenges that hinder the integration of local knowledge into higher education curricula in Aceh. A consistent concern among participants was the lack of institutional guidelines. Although the national

Merdeka Belajar policy encourages contextualization, many universities have not developed internal regulations or curriculum blueprints to operationalize the integration of local content. As a result, educators were left without clear directives or quality benchmarks, leading to fragmented or informal practices.

Another significant barrier was the limited capacity of lecturers. Respondents expressed that most teaching staff had not received adequate training in Culturally Responsive Pedagogy or interdisciplinary curriculum design. This lack of capacity made it difficult for lecturers to confidently embed local knowledge into their syllabi or employ relevant assessment methods. Moreover, the misalignment between the localized content and national accreditation standards was a recurring theme. Many participants feared that innovative, locally grounded modules might not fulfill standardized criteria set by national assessment bodies, thus threatening institutional performance indicators. Administrative support was also reported as insufficient. Several lecturers highlighted a lack of budgetary allocation, the absence of leadership support, and a general lack of institutional prioritization for integrating local knowledge. These limitations created practical barriers to implementation, even when faculty enthusiasm was high.

Finally, participants pointed to bureaucratic rigidity as a structural obstacle. Curriculum design and academic credit allocation remain highly centralized and inflexible, leaving little room for innovation. The pressure to adhere to strict program structures often discourages experimentation and adaptation, which are necessary for embedding local content in a meaningful way. Together, these challenges underscore the gap between national educational aspirations and institutional realities. Without systemic changes at both policy and administrative levels, efforts to incorporate local knowledge risk being inconsistent, symbolic, or unsustainable. Addressing these barriers is crucial for establishing a truly contextualized and culturally responsive higher education system in Indonesia.

5.3.4. Enabling Factors and Opportunities for Innovation

Several key enabling factors have supported the integration of local knowledge into higher education curricula in Aceh. Institutional leadership, particularly from rectors and deans, played a critical role in legitimizing curriculum reform, as reflected in the statement, “The Rector supported our local module and gave it a dedicated course slot.” Community–academic partnerships also contributed significantly, with syllabi often co-developed alongside village elders and NGOs, fostering culturally grounded content. Faculty-level autonomy enabled flexible curriculum adaptation without compromising national learning standards. As one lecturer stated, “We could adapt our modules as long as learning outcomes were met.” Moreover, research-based development—utilizing student theses and local fieldwork—enabled local knowledge to be recognized as academically rigorous, while cross-disciplinary collaboration created space for innovative teaching practices, such as modules jointly designed by engineering and anthropology students. Collectively, these factors highlight a dynamic process of curriculum innovation that bridges academic standards with local cultural relevance.

The integration of local knowledge into higher education in Aceh has been enabled by a set of institutional and pedagogical factors that collectively foster innovation. As presented in

Table 8, institutional leadership played a pivotal role. Support from rectors, deans, or program heads created strategic momentum, whether through policy endorsements, course allocations, or resource provision. Participants consistently emphasized the importance of top-down encouragement in legitimizing efforts to localize curricula. Equally important were community–academic partnerships, particularly those that included village elders, traditional leaders, religious figures, or local NGOs. These collaborations not only enriched the course content but also fostered mutual trust and relevance. In some cases, entire syllabi were co-developed with community input, ensuring that the academic content remained grounded in a social context.

A critical enabling condition was curriculum autonomy at the faculty level. Faculties with flexibility in course design were able to innovate while still aligning with accreditation standards. Respondents noted that as long as learning outcomes were maintained, locally grounded materials could be introduced without bureaucratic constraints.

Several lecturers described how research-based content development, especially from student theses or faculty fieldwork, contributed to the formal curriculum. This not only created a feedback loop between research and teaching but also validated local knowledge as academically rigorous. Additionally, cross-disciplinary collaboration enabled different faculties to integrate local perspectives into diverse fields, such as disaster education, sustainable agriculture, and public health. Collectively, these enabling factors demonstrate that local knowledge integration is not only a cultural imperative but also an institutional innovation process, one that thrives on leadership, flexibility, collaboration, and grounded research.

The integration of local knowledge into higher education in Aceh is the result of collaborative efforts involving multiple stakeholders, each playing distinct but complementary roles in curriculum innovation. As illustrated in

Table 9, lecturers are at the forefront of curricular adaptation, embedding themes such as

adat (customary law), traditional ecological knowledge, and oral literature into course syllabi. They also implement innovative pedagogical approaches, such as reflective journals, problem-based learning, and contextual storytelling, while supervising students in community-based projects. Institutional leaders—such as rectors and deans—provide strategic support by approving localized courses, allocating resources, and promoting programs like

Kuliah Kerja Nyata (Community Service-Learning) and applied research initiatives. Curriculum developers act as mediators between national policy and institutional practice, ensuring that learning outcomes incorporate cultural relevance through community consultations. Community leaders, including traditional and religious figures, contribute cultural legitimacy by participating in syllabus design, delivering guest lectures, and facilitating participatory learning activities. Students, meanwhile, serve as cultural intermediaries, conducting locally grounded projects and producing academic work that validates Indigenous perspectives. This narrative highlights that local knowledge integration is not an isolated academic endeavor but a systemic reform process driven by a shared commitment and cross-sector collaboration.

Table 10 presents the empirical validation of key elements influencing the integration of local knowledge into higher education curricula. The findings indicate that lecturer capacity plays a critical role, with 62% of lecturers having attended at least two CRP-based training sessions. Notably, lecturers who participated in more than two trainings integrated Acehnese cultural content into approximately 70% of their courses, suggesting a positive correlation between training participation and curriculum localization. The institutional policy also emerged as a significant driver. Three out of five universities had explicit cultural integration policies, with an average of 5% of curriculum development funds allocated to this purpose. This demonstrates a causal link in which formal policy frameworks, coupled with dedicated budgets, lead to sustained integration efforts and broader module coverage.

Student engagement was notably higher in institutions offering structured cultural modules, with over 80% participation in community-based learning and local knowledge projects. Students in these contexts reported greater perceived relevance and motivation, underscoring the positive relationship between structured cultural integration and active learning engagement. Finally, stakeholder involvement strengthened the authenticity and applicability of the integrated content. Across the participating universities, 15 Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) were signed with local communities, and joint curriculum meetings were held quarterly. This strong association between community partnerships and curriculum design highlights the importance of collaborative approaches in ensuring that integrated content remains culturally authentic and contextually relevant.

6. Discussion

This study’s findings contribute to a growing body of literature emphasizing the importance of culturally responsive education, particularly in regions with rich socio-historical contexts such as Aceh. The integration of local knowledge into higher education curricula aligns with global movements advocating for educational equity, identity formation, and contextual relevance. Within the framework of Indonesia’s Merdeka Belajar policy, the experiences documented in Aceh reveal both opportunities and constraints, highlighting how institutional autonomy, community collaboration, and curricular flexibility serve as enabling factors, while bureaucratic and accreditation challenges persist. The following discussion situates these findings within broader educational debates, offering comparative insights and practical recommendations for policy and institutional reform.

6.1. Alignment with Global Movements for Culturally Relevant Education

The findings of this study strongly align with global educational discourses that advocate for culturally relevant and inclusive curricula. Culturally responsive teaching is fundamental to student engagement and identity development, particularly in multicultural and Indigenous contexts (

Anyichie et al., 2023). Underscores the importance of integrating local and Indigenous knowledge systems into formal education as part of a broader effort to promote education that is inclusive, equitable, and sustainable (

El Yazidi & Rijal, 2024).

In the case of Aceh, the integration of local knowledge, encompassing adat (customary law), oral literature, and ecological traditions, reflects this global momentum. It mirrors curricular reforms observed in Indigenous education models in countries such as Canada and Australia, where First Nations and Aboriginal perspectives have been embedded within school and university curricula (

Weuffen et al., 2024). Such practices validate local epistemologies and challenge the dominance of Eurocentric or standardized content.

Recent research further supports this shift. For instance, preview research highlighted how contextualized linguistic and cultural materials in Indonesian education foster deeper learning and linguistic pride (

Fitriadi et al., 2024). Similarly, other researchers have demonstrated that incorporating community-based knowledge in Southeast Asian teacher training enhances pedagogical relevance and cultural sensitivity (

Teo et al., 2021). These studies affirm that education systems must reflect the lived realities of learners to foster a stronger sense of belonging and educational justice. By situating Aceh’s curricular innovations within this global trend, this study affirms that the integration of local knowledge is not merely a regional necessity but a critical contribution to the universal discourse on decolonizing education and promoting epistemic justice.

6.2. The Implications of Integrating Local Knowledge Within National Frameworks

The integration of local knowledge within Indonesia’s national curriculum framework reveals inherent tensions between standardization and contextualization. While national education standards, particularly accreditation rubrics, prioritize measurable, universal learning outcomes, they often lack indicators that acknowledge or value locally grounded pedagogical approaches. This dissonance presents significant challenges for institutions that seek to innovate through culturally responsive content while maintaining compliance with national quality assurance systems (

Chandler, 2025).

The Merdeka Belajar policy offers a strategic window for change, promoting flexibility, autonomy, and the recontextualization of the curriculum. However, as this study found, many lecturers and curriculum developers expressed uncertainty due to the absence of clear technical guidelines for integrating local knowledge within accredited course structures. This ambiguity creates a policy–practice gap, where educators are encouraged to innovate but face institutional constraints when attempting to formalize localized materials within official syllabi (

Wong-Villacres et al., 2024).

Institutional autonomy emerges as a critical enabler. Faculties and departments with greater curricular discretion have been more successful in embedding local knowledge through elective modules, community partnerships, or co-designed syllabi. These practices align with a previous study that noted that educational institutions with decentralized governance models are more agile in implementing context-sensitive reforms (

Lukman & Hakim, 2024). Autonomy fosters innovation without undermining national benchmarks, particularly when supported by visionary leadership and participatory curriculum design. To reconcile national frameworks with local pedagogical aspirations, clearer operational standards, capacity-building for lecturers, and reforms to accreditation are needed (

Khan & Wali, 2020). These steps would empower institutions to uphold both academic rigor and cultural relevance, ensuring that education remains meaningful in diverse sociocultural contexts, such as Aceh.

6.3. Comparative Insights with Other Regions and Countries

The integration of local knowledge into higher education in Aceh reflects broader trends observed both nationally and internationally, where culturally rooted education models have gained prominence. Within Indonesia, similar efforts are seen in regions such as Papua and Bali, where the local culture is integrated not only as curricular content but also as a philosophical foundation for pedagogy and community engagement. For instance, educational institutions in Papua have embedded Indigenous ecological knowledge and oral traditions to support place-based learning (

Fiharsono et al., 2024), while Bali’s education system incorporates Hindu epistemologies into civic and moral education (

Suardana et al., 2023).

Internationally, Aceh’s initiatives parallel the integration of Indigenous perspectives in New Zealand and Canada. New Zealand’s inclusion of Mātauranga Māori in curricula has been instrumental in promoting bicultural understanding and validating Indigenous epistemologies (

Farnan-Sestito, 2024). In Canada, universities have increasingly partnered with First Nations communities to co-develop curriculum content, indigenize campus spaces, and reframe knowledge systems beyond Eurocentric models (

Müller, 2024). Likewise, Southeast Asian models, particularly in Thailand and the Philippines, demonstrate the effectiveness of community-based learning in anchoring education to local realities. In Thailand, Wisdom Schools integrate academic instruction with traditional agricultural practices (

Pascua, 2023). In contrast, in the Philippines, the Bayanihan-based pedagogy promotes social cohesion and contextual learning (

Adlit & Martinez, 2023).

What distinguishes Aceh’s approach is its unique Islamic cultural framework, which simultaneously offers rich educational resources and poses certain constraints. While Islamic values enhance character education and provide a moral basis for integrating local wisdom such as hikmah, adat, and religious traditions, they also necessitate alignment with religious authorities and doctrinal norms, which can limit pedagogical experimentation. This complexity, while challenging, provides a valuable lens through which Aceh’s curriculum innovation can be understood as a hybrid model that bridges religious, cultural, and academic imperatives. This model brings a distinctive perspective to the global discourse on culturally relevant pedagogy in higher education.

6.4. Hidden Curriculum and the Social-Cultural Dimensions of Knowledge

Beyond its explicit content, a curriculum carries implicit values, norms, and behavioral expectations commonly referred to as the

hidden curriculum. In the context of integrating local knowledge into higher education, these embedded elements often reflect deep-seated community values, social hierarchies, and cultural narratives. For instance, Aceh’s local curriculum elements emphasize collective responsibility, religious adherence, and respect for elders, which can strengthen social cohesion among students. However, such values may also contrast with elements in standardized international curricula that emphasize individual achievement, competition, and secular frameworks (

Hidayati & Nihayah, 2025). From the field data, several lecturers reported that while local traditions foster a sense of belonging, they occasionally conflict with competency-based, globally benchmarked learning outcomes. This tension suggests that local knowledge integration requires a deliberate design strategy that makes these value systems explicit, thereby enabling educators and students to navigate and reconcile differing epistemologies critically.

6.5. Balancing Local and International Curriculum Standards

Balancing the preservation of local values with the demands of global academic standards remains a persistent tension in curriculum reform. The findings of this study reveal that potential points of conflict often arise in three key areas: value orientations, where the collectivism embedded in the local culture contrasts with the individualism emphasized in global academic benchmarks; epistemological foundations, where community-based oral traditions differ from Western empirical and written traditions; and pedagogical approaches, where context-driven, experiential learning may conflict with standardized, outcomes-based assessments. To address these challenges, a hybrid integration model is proposed, combining culturally grounded learning activities with globally recognized competencies. For instance, community service projects rooted in local customs could be aligned with internationally recognized graduate attributes such as problem-solving, critical thinking, and intercultural communication (

Meland & Brion-Meisels, 2024). From a policy perspective, it is recommended that quality assurance frameworks explicitly incorporate cultural relevance as a criterion alongside conventional academic standards. Such an approach would enable higher education institutions in culturally diverse regions, such as Aceh, to achieve global benchmarks while preserving and promoting their local heritage.

6.6. Policy and Institutional Recommendations

The practical recommendations emerging from this study align closely with the principles of CRP, underscoring the necessity of valuing students’ cultural identities as assets in the learning process, while curriculum contextualization advocates for the adaptation of educational content to sociocultural realities without sacrificing academic rigor (

Ibiloye, 2025). In the Acehnese higher education context, these frameworks collectively support the development of curricula that embed local knowledge, such as adat, oral traditions, and ecological wisdom, into teaching strategies, thereby enhancing both relevance and engagement. From a policy perspective, these findings suggest that higher education authorities in culturally diverse regions should explicitly incorporate cultural relevance as a criterion within quality assurance frameworks. This would not only legitimize the integration of local knowledge but also ensure that institutional practices are aligned with global academic standards. For example, policy directives could mandate that a proportion of curriculum credits be allocated to culturally grounded learning activities that are mapped against internationally recognized graduate competencies, such as problem-solving, critical thinking, and intercultural communication.

The findings of this study highlight several actionable pathways for strengthening the integration of local knowledge into higher education through systemic and institutional reforms. First, national accreditation agencies should revise their evaluation frameworks to include indicators that explicitly assess the integration of local knowledge. Current accreditation mechanisms in Indonesia primarily emphasize standardized competencies and global benchmarks, which often marginalize culturally contextual innovations. Embedding indicators for local wisdom would align with the broader goals of

Merdeka Belajar and reinforce curriculum autonomy (

Umayah, 2024).

Second, institutions must invest in capacity-building programs for lecturers, focusing on Culturally Responsive Pedagogy and curriculum contextualization. Many lecturers in this study expressed interest in integrating local content, but they lacked formal training and resources. Capacity-building efforts such as workshops, short courses, and mentoring schemes can equip educators with the skills to navigate both academic standards and cultural authenticity (

Khan & Wali, 2020).

Third, community–university partnerships should be institutionalized as part of the curriculum design and delivery process. Structured collaborations with local leaders, NGOs, religious figures, and village elders can enhance the relevance and legitimacy of academic programs. These partnerships should extend beyond ad hoc guest lectures and evolve into co-design mechanisms, where communities actively shape the curricular content, particularly in applied and field-based courses (

Van Mechelen et al., 2023). Moreover, the Ministry of Education and institutional policymakers are encouraged to develop toolkits and operational guidelines for integrating local content. These tools should provide practical steps, model syllabi, and evaluation rubrics to help faculties navigate contextualization while maintaining compliance with national policies (

David, 2025). Successful models from provinces like Yogyakarta and West Sumatra demonstrate how regional autonomy and curricular flexibility can coexist (

Esti, 2021).

Lastly, curriculum reform efforts must involve multi-stakeholder participation, encompassing not just university actors but also regional governments, Islamic education councils, traditional institutions, and civil society. This inclusive approach ensures that local knowledge is not tokenized but embedded as a foundational pillar of learning, consistent with the vision of education as a public good that serves both the local identity and national progress.

6.7. Practical Curriculum Model Proposal

Table 11 presents a curriculum development matrix derived from the findings of this study in response to the need for systematically integrating local knowledge into higher education in Aceh. This matrix combines key curriculum components—namely core competencies, local content, learning methods, assessment strategies, and collaboration—with the engagement of key stakeholders, including lecturers, students, communities, and educational institutions. Each component is designed to balance universal academic values with local relevance, in line with the objectives of the Merdeka Belajar (Freedom to Learn) policy. For instance, contents such as customary law, traditional ecological systems, local history, and Islamic–Acehnese narratives are proposed to be incorporated into cross-disciplinary courses through project-based and collaborative learning approaches. Assessment strategies are also adapted to be more reflective and contextual, incorporating elements such as reflective journals, participatory mapping, and field-based presentations.

Furthermore, the model emphasizes the importance of local community partnerships and the strengthening of faculty autonomy in curriculum design. This matrix serves as a practical and adaptable tool for curriculum developers in designing and implementing learning models grounded in local wisdom. In doing so, the curriculum functions not only as a medium for knowledge transfer but also as a platform for cultural preservation and the reinforcement of students’ local identity.

The relevance of this study lies in its direct alignment with the educational needs and outcomes of Aceh, particularly in bridging higher education with local sociocultural contexts. By focusing on culturally contextualized curricula, this research addresses both the preservation of intangible cultural heritage and the enhancement of educational quality issues that are increasingly critical in regions with rich but underrepresented traditions. When placed in a global perspective, these findings resonate with similar efforts in diverse contexts such as Māori education in New Zealand, Indigenous higher education in Canada, and intercultural curriculum models in Latin America (

Santhakumar et al., 2020). Each of these cases highlights the dual challenge of maintaining cultural authenticity while ensuring global competitiveness—a challenge mirrored in Aceh’s higher education landscape.

Theoretically, this study strengthens the discourse on CRP and Curriculum Contextualization Theory by providing empirically grounded insights into how these frameworks can be adapted in post-conflict, culturally distinct regions (

Ramli et al., 2025). Practically, the findings inform policy and institutional strategies that not only address local needs but also align with international standards, offering a replicable model for other regions navigating similar cultural–educational intersections.

7. Conclusions

This study explored the integration of local knowledge into higher education curricula in Aceh, Indonesia, within the framework of the Merdeka Belajar policy. The findings indicate that local knowledge is widely recognized by educators, policymakers, and curriculum developers as a vital foundation for contextual and culturally relevant education. Integration is implemented through thematic content, community-based learning, and reflective assessment practices. However, persistent structural challenges remain, including limited institutional guidelines, insufficient lecturer capacity, and accreditation systems that prioritize standardized indicators over local relevance.

This research provides empirical insights into how educational innovation can emerge at the intersection of cultural identity, institutional autonomy, and national policy. It emphasizes that local knowledge is central to fostering inclusive and socially responsive higher education. It highlights the importance of collaborative networks linking universities, communities, and policy institutions to sustain culturally meaningful curricular transformations.

Adequate curriculum contextualization requires engaging with the underlying value systems embedded within educational structures. Recognizing and addressing the hidden curriculum is essential to preventing the marginalization of either local or global perspectives. Sustainable integration demands institutional strategies that mediate between differing value systems, producing a curriculum that is both locally relevant and globally competitive. Policies acknowledging these dual objectives, supported by capacity-building for lecturers in intercultural pedagogy, will be critical for long-term success. While this study offers valuable insights, its scope is limited to higher education institutions in Aceh. Future research should explore similar initiatives in other Indonesian provinces or undertake cross-national comparisons. Longitudinal studies would help assess the long-term impact of localized curricula on student outcomes, civic engagement, and academic relevance.

8. Practical Recommendations

Based on the findings and theoretical grounding, three key recommendations emerge for strengthening the integration of local knowledge in higher education. First, the implementation of mandatory cultural studies modules, developed collaboratively with local scholars and communities to ensure authenticity, should be systematically mapped against both national and international graduate competencies. Second, the incorporation of community-based research projects into degree programs can foster reciprocal knowledge exchange between students and local stakeholders, thereby enhancing academic rigor while ensuring social and cultural relevance. Third, the establishment of targeted faculty development programs in intercultural pedagogy is essential to equip lecturers with strategies aligned with Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP), enabling them to embed local knowledge effectively while meeting quality assurance and accreditation requirements. These recommendations hold relevance not only for Aceh but also for other Indigenous and culturally distinct contexts such as the Pacific Islands, Latin America, and Southeast Asia—where maintaining a balance between cultural preservation and global competitiveness remains a critical challenge.

9. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study is limited by its geographic focus on Aceh and its reliance on qualitative data, which, while providing rich and contextually nuanced insights, could benefit from triangulation with quantitative measures in future research. Further studies could explore the long-term impact of culturally contextualized curricula on graduate employability, academic performance, and community engagement. Comparative research across provinces or countries with similar sociocultural dynamics may also yield valuable insights into the scalability and adaptability of such integration models.

Another limitation lies in the constrained capacity of lecturers to integrate local knowledge into curricula—an issue rooted in broader institutional challenges. Factors such as limited formal training in Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP) and a lack of sustained professional development programs have hindered lecturers’ pedagogical and methodological readiness to adapt teaching materials to local cultural contexts. Although Indonesia’s higher education reaccreditation processes are conducted regularly, they tend to emphasize administrative compliance and quantitative outputs such as publication counts and student–faculty ratios rather than the cultural relevance of curricula.

Addressing this gap requires systemic reforms, including the integration of cultural responsiveness competencies into accreditation standards, mandatory CRP and curriculum contextualization training for lecturers, targeted funding and incentives for developing culturally grounded modules, and a shift toward impact-based monitoring and evaluation that measures community engagement and student learning outcomes. Enhancing the lecturer capacity must therefore proceed in tandem with accreditation policy reforms and sustained institutional support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R. (Ramli Ramli), R.R. (Razali Razali) and A.N.G.; methodology, R.R. (Ramli Ramli), R.R. (Razali Razali) and A.N.G.; software, R.R. (Ramli Ramli); validation, R.R. (Ramli Ramli), R.R. (Razali Razali) and A.N.G.; formal analysis, R.R. (Ramli Ramli); investigation, R.R. (Ramli Ramli), R.R. (Razali Razali) and A.N.G.; resources, R.R. (Ramli Ramli), R.R. (Razali Razali) and A.N.G.; data curation, R.R. (Ramli Ramli), R.R. (Razali Razali) and A.N.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R. (Ramli Ramli), R.R. (Razali Razali) and A.N.G.; writing—review and editing, R.R. (Ramli Ramli), R.R. (Razali Razali), A.N.G., N.D. and J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Universitas Syiah Kuala (approval code: 10586/ETIK-FKIP/USK/2024, approval date: 20 June 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the lecturers, curriculum developers, and policy stakeholders who participated in this study, as well as the institutional representatives who facilitated the research process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abubakar, A., Aswita, D., Israwati, I., Ferdianto, J., Jailani, J., Anwar, A., Ridhwan, M., Saputra, D. H., & Hayati, H. (2022). The implementation of local values in aceh education curriculum. Jurnal Ilmiah Peuradeun, 10(1), 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adlit, M. F., & Martinez, M. R. (2023). Reliving the bayanihan spirit: SPRCNHS landayan annex narratives in the new normal. Puissant, 4, 781–800. [Google Scholar]

- Ajani, O. A. (2025). Rethinking teacher development: Blending socially responsible teaching approaches with indigenous knowledge to enhance equity and inclusivity. SN Social Sciences, 5(4), 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Abri, M. H., Al Aamri, A. Y., & Elhaj, A. M. A. (2024). Enhancing student learning experiences through integrated constructivist pedagogical models. European Journal of Contemporary Education and E-Learning, 2(1), 130–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Husban, N., & Al’Abri, K. M. (2024). Cultivating global citizenship education in higher education: Learning from EFL university students’ voices. Citizenship Teaching & Learning, 19(1), 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Worafi, Y. M. (2024). Curriculum reform in developing countries: Public health education. In Handbook of medical and health sciences in developing countries: Education, practice, and research (pp. 1–26). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, T. (2024). Globalization and cultural homogenization: A critical examination. Kashf Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, 1(03), 10–20. [Google Scholar]

- Amiruddin, A., Nurdin, A., Yunus, M., & Gani, B. A. (2024). Social mainstreaming in the higher education independent curriculum development in Aceh, Indonesia: A mixed methods study. International Journal of Society, Culture & Language, 12(1), 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Anyichie, A. C., Butler, D. L., Perry, N. E., & Nashon, S. M. (2023). Examining classroom contexts in support of culturally diverse learners’ engagement: An integration of self-regulated learning and culturally responsive pedagogical practices. Frontline Learning Research, 11(1), 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, Y., & Mohammed, S. J. (2022). Indigenous-based adult education learning material development: Integration, practical challenges, and contextual considerations in focus. Education Research International, 2022(1), 2294593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, B. (2000). Pedagogy, symbolic control, and identity. Bloomsbury Academic. Available online: https://books.google.co.id/books?id=_V0L-6eTYUAC (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Brondízio, E. S., Aumeeruddy-Thomas, Y., Bates, P., Carino, J., Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Ferrari, M. F., Galvin, K., Reyes-García, V., McElwee, P., & Molnár, Z. (2021). Locally based, regionally manifested, and globally relevant: Indigenous and local knowledge, values, and practices for nature. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 46(1), 481–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, J. D. (2025). Institutional dissonance and innovation: Higher education from a service ecosystems perspective. Journal of Service Management, 36(2), 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-C., & Viesca, K. M. (2022). Preparing teachers for culturally responsive/relevant pedagogy (CRP): A critical review of research. Teachers College Record, 124(2), 197–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimbutane, F. (2023). Multilingualism and languages of learning and teaching in post-colonial Sub-Saharan Africa. In The Routledge handbook of multilingualism (pp. 207–222). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- David, J. O. (2025). Redefining assessment for sustainability: A reflective approach to curriculum transformation in environmental education. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1553999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Yazidi, R., & Rijal, K. (2024). Science learning in the context of’indigenous knowledge’for sustainable development. International Journal of Ethnoscience and Technology in Education, 1(1), 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]