Reflective Insights into Undergraduate Public Health Education: Comparing Student and Stakeholder Perceptions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Setting, and Ethics Approval

2.2. Quantitative Phase

2.3. Quantitative Part of the Survey Questionnaire

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Qualitative Phase

2.6. Qualitative Part of the Survey Questionnaire

2.7. Qualitative Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Results

3.1.1. Demographic Characteristics of Participants

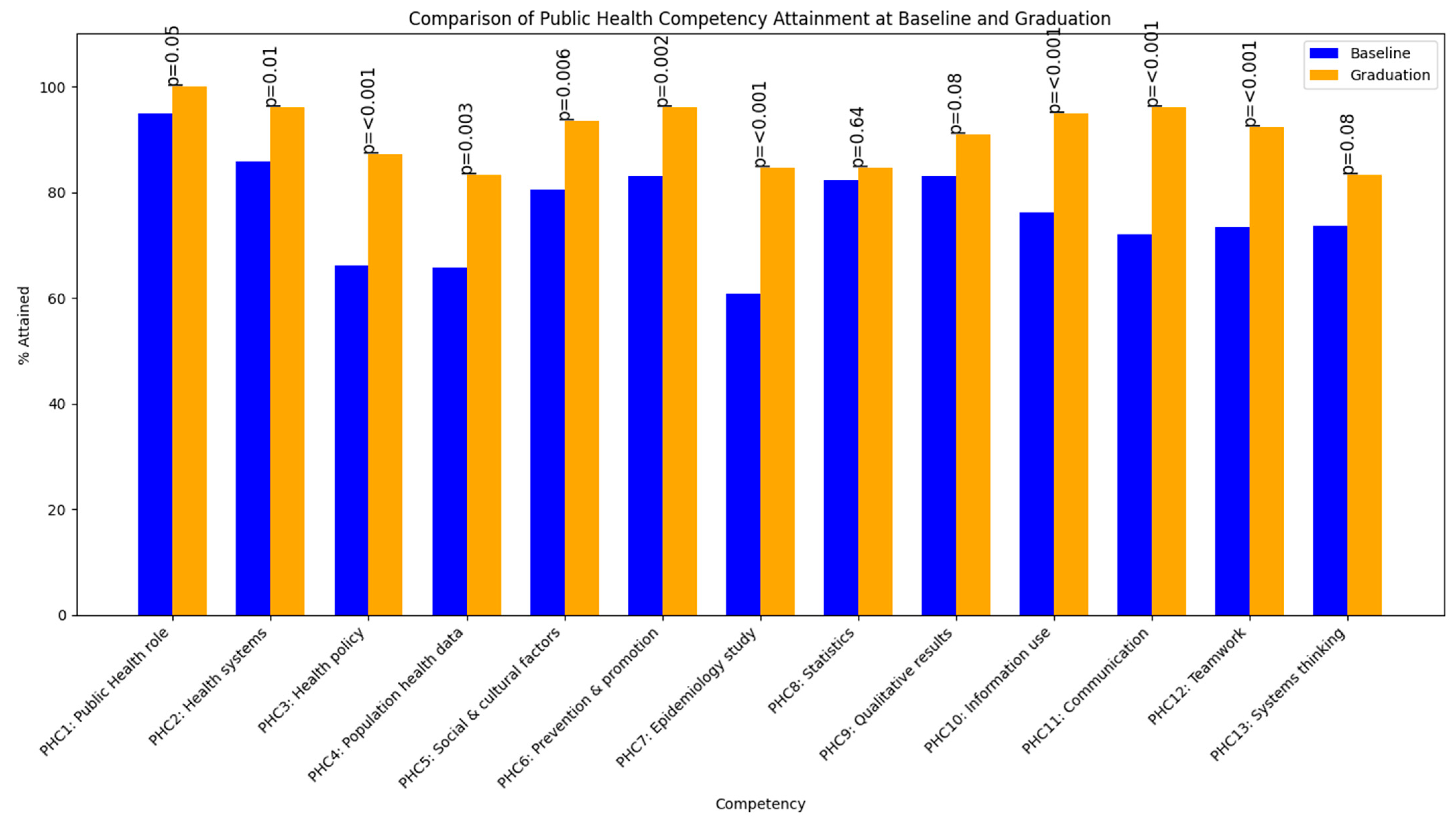

3.1.2. Attainment of Public Health Competencies at Baseline and Graduation by Students

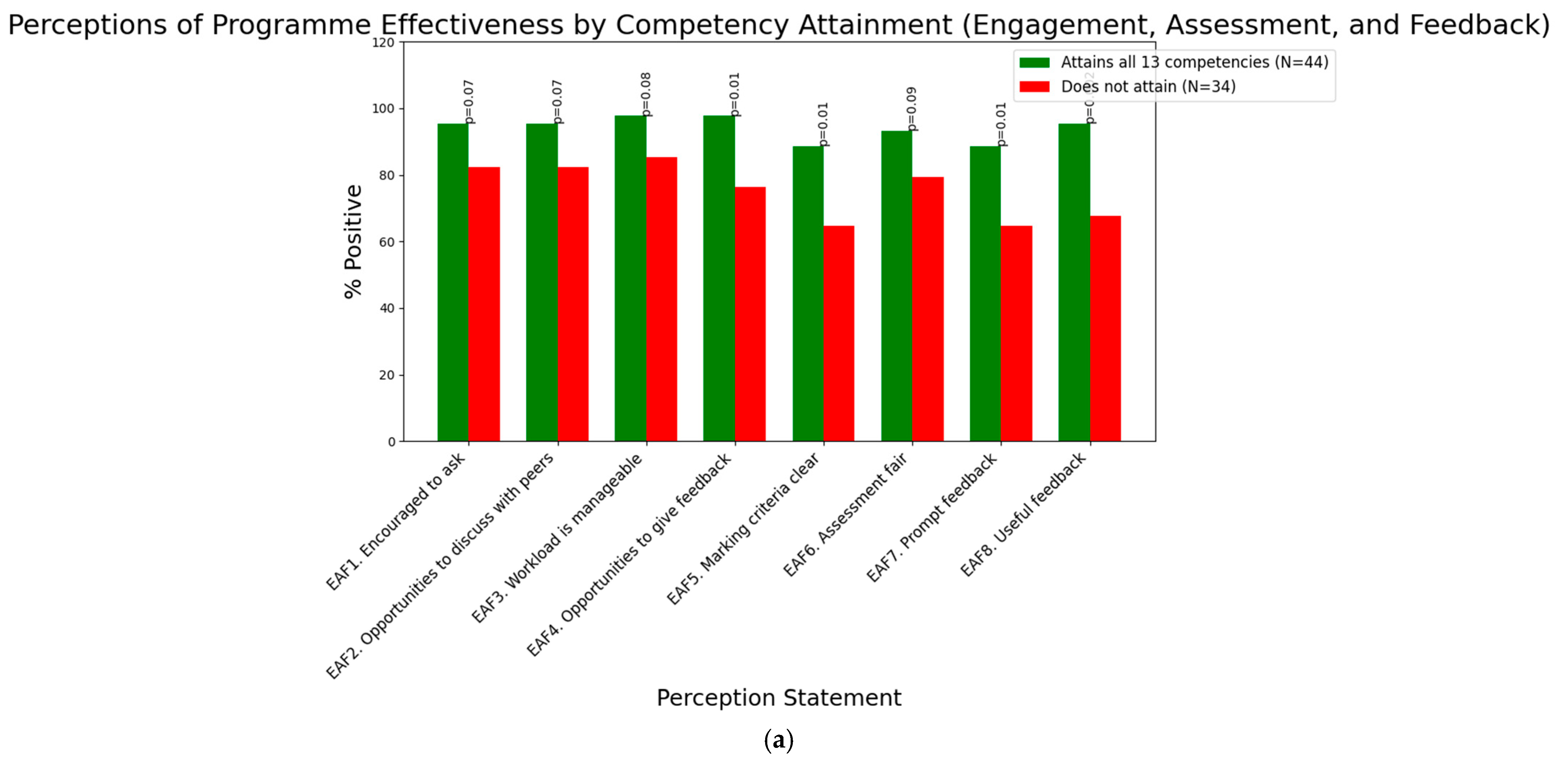

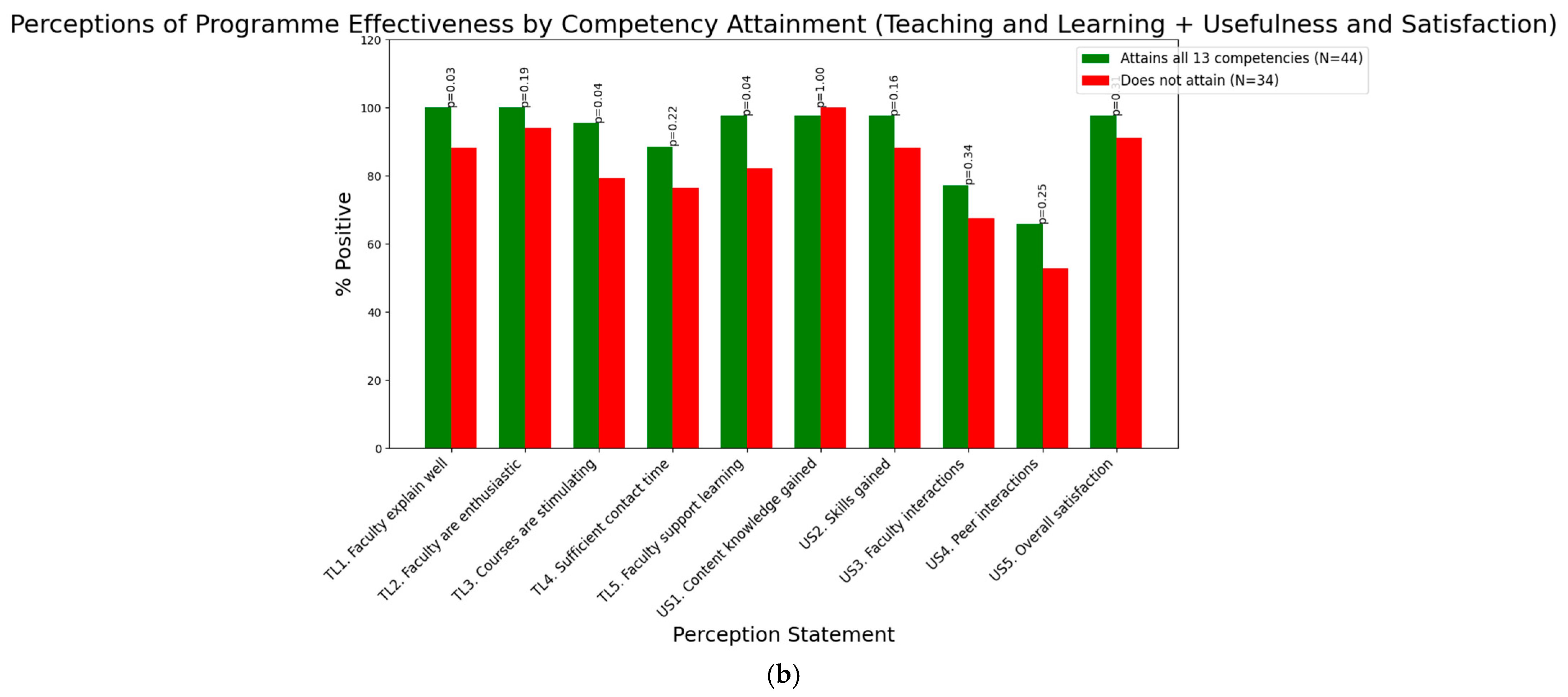

3.1.3. Perceptions of Programme Effectiveness by Attainment of Competencies in Graduating Students

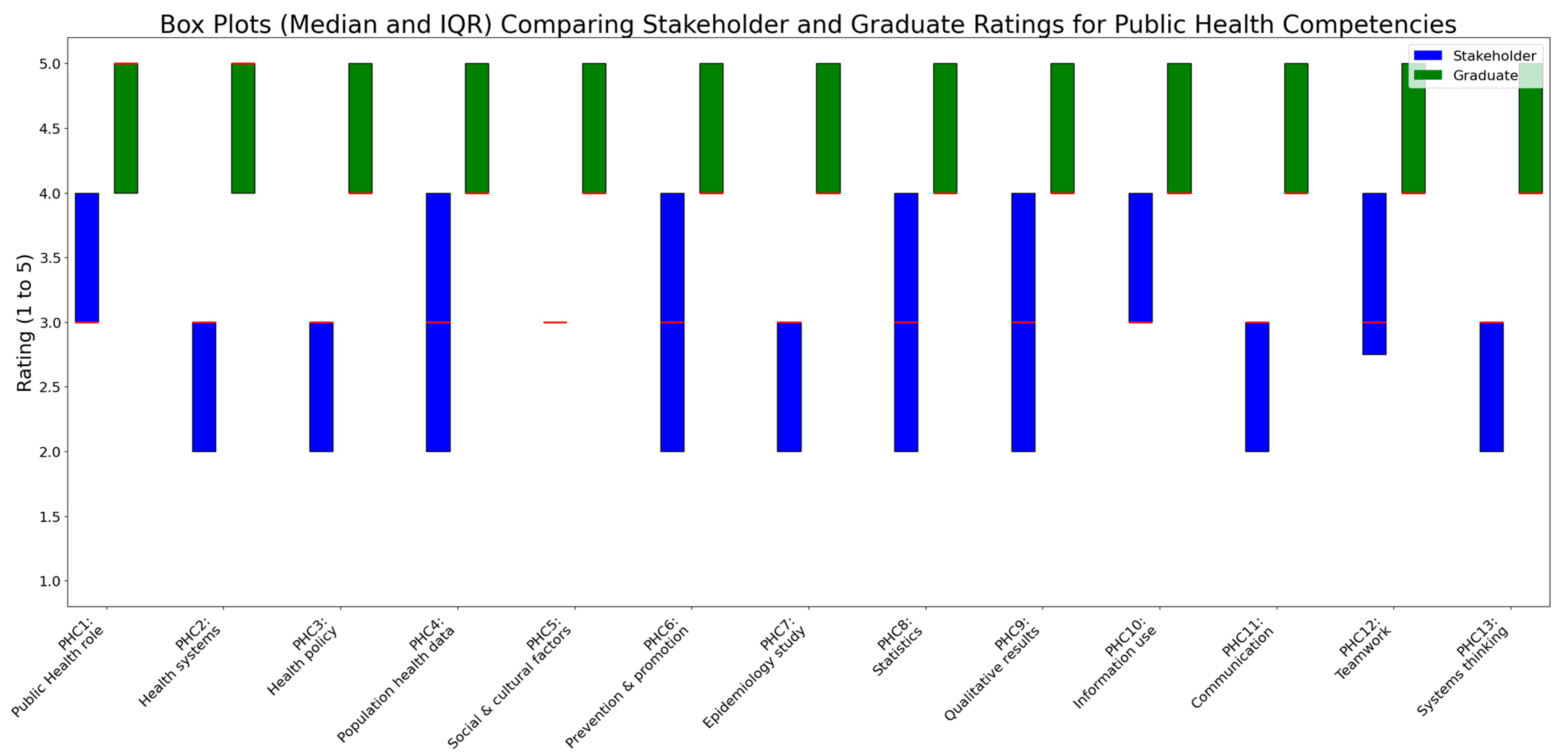

3.1.4. Comparative Analysis of Public Health Competencies Between Graduating Students and Industry Stakeholders

3.2. Qualitative Results

3.2.1. Strengths in the Training of Graduating Students

3.2.2. Gaps in the Training of Graduating Students

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Results and Integration of Quantitative and Qualitative Findings

4.2. Comparison of Results with Existing Literature

4.3. Implications of Results and Recommendations for Enhancing Undergraduate Public Health Education

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

4.5. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEPH | Council on Education for Public Health |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| EAF | Engagement, Assessment, and Feedback |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| NUS | National University of Singapore |

| PHC | Public Health Competency |

| RQ | Research Question |

| SSHSPH | Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health |

| TL | Teaching and Learning |

| US | Usefulness and Satisfaction |

Appendix A

| Competency | Description |

|---|---|

| PHC1 | Understand the role of public health in society |

| PHC2 | Understand the role and function of health delivery systems |

| PHC3 | Understand the processes of health policy formulation and implementation |

| PHC4 | Use data from various sources to characterise the health of a population or subpopulation |

| PHC5 | Identify political, cultural, behavioural, and socioeconomic factors related to common public health issues |

| PHC6 | Apply basic preventive approaches to disease prevention and health promotion for the individuals and community |

| PHC7 | Design and conduct a basic epidemiological study (define aims, select appropriate study designs, collect, analyse, and interpret data, identify limitations, summarise and discuss findings) |

| PHC8 | Interpret basic statistical results |

| PHC9 | Interpret basic qualitative results |

| PHC10 | Locate, use, and evaluate public health information |

| PHC11 | Communicate public health information in both verbal and written forms |

| PHC12 | Work effectively as a member of a public health team |

| PHC13 | Adopt a systems thinking approach in tackling public health issues |

| Domain | Perception Statement |

|---|---|

| Engagement, assessment, and feedback (EAF) | I am encouraged to ask questions or make contributions in class. (EAF1) |

| The Minor in Public Health has created sufficient opportunities to discuss my work with other students. (EAF2) | |

| The workload in the Minor in Public Health is manageable. (EAF3) | |

| I have appropriate opportunities to give feedback on my experience. (EAF4) | |

| The criteria used in marking is made clear in advance. (EAF5) | |

| Assessment arrangements and marking are fair. (EAF6) | |

| Feedback on my work is prompt. (EAF7) | |

| Feedback on my work (written or verbal) is useful. (EFA8) | |

| Teaching and learning (TL) | Faculty are good at explaining things. (TL1) |

| Faculty are enthusiastic about what they are teaching. (TL2) | |

| The courses are academically stimulating. (TL3) | |

| There is sufficient contact time (face-to-face and/or virtual/online) between faculty and students to support effective learning. (TL4) | |

| I am happy with the support I receive from faculty for my learning. (TL5) | |

| Usefulness and satisfaction of programme (US) | Content knowledge acquired through the Minor. (US1) |

| Skill sets acquired through the Minor. (US2) | |

| Interactions with faculty. (US3) | |

| Interactions with fellow course-mates taking the Minor. (US4) | |

| Overall, I am satisfied with the quality of the Minor. (US5) |

References

- AlMubarak, S. H. (2023). Students as policymakers and policy advocates: Role-playing evidence-based health policies. Simulation & Gaming, 54(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong-Mensah, E. A., Ramsey-White, K., Alema-Mensah, E., & Yankey, B. A. (2022). Preparing students for the public health workforce: The role of effective high-impact educational practices in undergraduate public health program curricula. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 790406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, P. R. A., Carroll, J. A., & Demant, D. (2024). Innovative strategies for public health training in the Asia Pacific: Insights from experience and evidence. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 37(1), 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertilsson, E., Hall, S., Bowden, M., Townshend, J., & Kelly, F. (2023). Stakeholder role in setting curriculum priorities for expanding pharmacy scope of practice. Pharmacy Education, 23(1), 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Brînzac, M. G., Verschuuren, M., Leighton, L., & Otok, R. (2025). Public health competencies: What does the next generation of professionals deem important? European Journal of Public Health, 35(Suppl. 2), ii11–ii16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brondani, M. A., Pattanaporn, K., & Aleksejuniene, J. (2014). How can dental public health competencies be addressed at the undergraduate level? Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 75(1), 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecilia, S. A., Sorensen, C., Perera, G. F. S., Pedersen, C. B. M., Ebi, K. L., & Sheehan, M. C. (2024). The integration of climate change and adaptation into health professions curricula: A scoping review of the literature and course offerings. The Lancet Planetary Health, 8(1), e66–e74. [Google Scholar]

- Chidwick, H., Kapiriri, L., & Mak, A. (2024). Stakeholder perspectives of experiential education in tertiary institutions and learning from COVID 19. SAGE Open, 14(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombe, L., Severinsen, C., & Robinson, P. (2020). Practical competencies for public health education: A global analysis. International Journal of Public Health, 65, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council on Education for Public Health. (2021). Accreditation criteria: Schools of public health & public health programs. Available online: https://media.ceph.org/documents/2021.Criteria.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell, T. L., & Calamidas, E. (2016). Assessing public health majors through the use of e-portfolios. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 16(4), 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evashwick, C. J., Tao, D., & Arnold, L. D. (2014). The peer-reviewed literature on undergraduate education for public health in the United States, 2004–2014. Frontiers in Public Health, 2, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffar, A., Rashid, S. F., Wanyenze, R. K., & Hyder, A. A. (2021). Public health education post-COVID-19: A proposal for critical revisions. BMJ Global Health, 6(4), e005669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honicke, T., Broadbent, J., & Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. (2023). The self-efficacy and academic performance reciprocal relationship: The influence of task difficulty and baseline achievement on learner trajectory. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(8), 1936–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M. B., Ogunlayi, F., Middleton, J., & Squires, N. (2023). Strengthening capacity through competency-based education and training to deliver the essential public health functions: Reflection on roadmap to build public health workforce. BMJ Global Health, 8(3), e011310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, S. K., Entwistle, C., Magaña, L., Seward, T. G., & Joshi, A. (2024). A narrative review of the CEPH-accredited bachelor’s public health programs’ curricula in the United States. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1436386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiviniemi, M. T., & Przybyla, S. M. (2019). Integrative approaches to the undergraduate public health major curriculum: Strengths, challenges, and examples. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leethongdissakul, S., Chada, W., Tatiyaworawattanakul, K. H., & Turnbull, N. (2024). Mapping essential competencies: Informing curriculum development for public health education in Thailand. Journal of Infrastructure, Policy and Development, 8(7), 5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leistner, C. E., Machado, S. S., Gallardo, B., & McCommon, A. (2023). Teaching public health program planning: Service learning in an online format. Pedagogy in Health Promotion, 9(1), 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. W., Eden, R., Garber, C., Rudnick, M., Santibañez, L., & Tsai, T. (2014). Equity in competency education: Realizing the potential, overcoming the obstacles. Jobs for the Future. Available online: https://www.jff.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Equity-in-Competency-Education-103014.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Li, X., Zheng, X., Wen, B., Zhang, B., Xing, X., Zhu, L., Gu, W., & Wang, S. (2025). Design and assessment of a public health course as a general education elective for non-medical undergraduates. Frontiers in Public Health, 13, 1496283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R. B. T., Tan, C. G. L., Voo, K., Lee, Y. L., & Teng, C. W. C. (2024). Student perspectives on interdisciplinary learning in public health education: Insights from a mixed-methods study. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1516525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R. B. T., Teng, C. W. C., Azfar, J., Bun, D., Goh, G. J., & Lee, J. J.-M. (2020). An integrative approach to needs assessment and curriculum development of the first public health major in Singapore. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, M., Ford, C., Grant, L. E., Papadopoulos, A., & McWhirter, J. E. (2023). Developing public health competency statements and frameworks: A scoping review and thematic analysis of approaches. BMC Public Health, 23, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, M., McAlpine, D., Grant, L. E., Papadopoulos, A., & McWhirter, J. E. (2025). Assessing communication competencies in Canadian MPH programme curriculum: A content analysis of communication courses. Public Health, 139(2), 218–228. [Google Scholar]

- MacKay, M., McAlpine, D., Wrote, H., Grant, L. E., Papadopoulos, A., & McWhirter, J. E. (2024). Public health communication professional development opportunities and alignment with core competencies: An environmental scan and content analysis. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 44(5), 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, K., Gordon, J., & MacLeod, A. (2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 14(4), 595–621. [Google Scholar]

- Mirbahai, L., Noordali, F., & Nolan, H. (2024). Designing an interdisciplinary health course: A qualitative study of undergraduate students’ experience of interdisciplinary curriculum design. Journal of Education and Health, 30(1), 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson-Hurwitz, D. C., & Buchthal, O. V. (2019). Using deliberative pedagogy as a tool for critical thinking and career preparation among undergraduate public health students. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osiecki, K., Barnett, J., & Mejia, A. (2022). Creating an integrated undergraduate public health curricula: Inspiring the next generation to solve complex public health issues. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 864891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Przybyla, S. M., Cprek, S. E., & Kiviniemi, M. T. (2022). Infusing high-impact practices in undergraduate public health curricula: Models, lessons learned, and administrative considerations from two public universities. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 958184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, B., Leider, J. P., & Riegelman, R. (2018). The landscape of US undergraduate public health education. Public Health Reports, 133(5), 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, B., Selig, S., & Riegelman, R. (2017). An examination of the growing US undergraduate public health movement. Public Health Reviews, 38(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saud, H., & Chen, R. (2018). The effect of competency-based education on medical and nursing students’ academic performance, technical skill development, and overall satisfaction and preparedness for future practice: An integrative literature review. International Journal of Health Sciences Education, 5(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & DiBenedetto, M. K. (2020). Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 60, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Versluis, M. A. C., Jöbsis, N. C., Jaarsma, A. D. C., Tuinsma, R., & Duvivier, R. (2023). International health electives: Defining learning outcomes for a unique experience. BMC Medical Education, 23, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation. (2023). Global competency and outcomes framework for the essential public health functions. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/376577/9789240091214-eng.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Zheng, B., He, Q., & Lei, J. (2024). Informing factors and outcomes of self-assessment practices in medical education: A systematic review. Annals of Medicine, 56(1), 2421441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (a) | ||

| Demographic Characteristic | Baseline (n = 289) n (%) | Graduation (n = 78) n (%) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 92 (31.8) | 20 (25.6) |

| Female | 197 (68.2) | 58 (74.4) |

| First Major | ||

| Science | 179 (61.9) | 48 (61.5) |

| Non-Science | 110 (38.1%) | 30 (38.5) |

| Mean age in years (standard deviation) | 21.7 (1.6) | 23.2 (1.1) |

| (b) | ||

| Demographic Characteristic | Total (n = 17) n (%) | |

| Organisation | ||

| Government agencies/Ministries/Statutory boards | 2 (11.8) | |

| Hospitals/Polyclinics/Healthcare | 8 (47.1) | |

| Non-governmental/Non-profit organisations | 4 (23.5) | |

| Private organisations | 3 (17.6) | |

| Title Designation | ||

| Chief Executive Officer | 1 (5.9) | |

| Deputy Director | 2 (11.8) | |

| Director | 5 (29.4) | |

| Research Fellow | 2 (11.8) | |

| Manager | 4 (23.5) | |

| Assistant Manager | 2 (11.8) | |

| Executive | 1 (5.9) | |

| (a) | |||

| Theme | Subtheme | Illustrative Quote from Graduating Students | Illustrative Quote from Industry Stakeholders |

| Public Health Knowledge and Frameworks | Systems Thinking and Holistic Perspective | “The systems thinking approach taught is applicable even outside of public health and has complemented the thinking approach taught in my major (psychology)—A deeper understanding and appreciation of public health systems, policies, and issues” (Female, first major in psychology) | “They demonstrate a strong grasp of Singapore’s healthcare ecosystem and its interconnected components” (Industry stakeholder from IHH Healthcare) |

| Familiarity with Public Health Concepts | “The programme exposed me to key public health concepts and terminology, giving me a solid foundation to discuss health issues” (Female, first major in global studies) | “These hires are familiar with public health terminology and show an interest in health, which helps to lower the probability of attrition” (Industry stakeholder from Agency for Integrated Care) | |

| Analytical and Problem-Solving Skills | Quantitative and Research Skills | “Able to learn different skillsets and knowledge, like interpreting data, presenting information, etc.” (Male, first major in business) | “Hires contribute public health perspectives and skillsets to social programmes, including critical appreciation of risk and protective factors affecting health outcomes, as well as quantitative analysis skills” (Industry stakeholder from TOUCH Community Services) |

| Systems-Based Policy Design | “Encourages us to think of creative, yet targeted policies which consider holistic aspects of one’s health, the built and natural environment. Adopting a systems thinking approach is useful in tackling public health issues too” (Female, first major in life sciences) | “They excel at designing policies that address macro health issues using a systems approach” (Adjunct faculty and management from the National Centre for Infectious Diseases) | |

| Interdisciplinary Synergy and Career Enhancement | Cross-Disciplinary Integration | “It compliments [sic] many different majors” (Female, first major in sociology) | “They are able to give a public health perspective in approaching solutions and are competent in basic research design and analysis” (Industry stakeholder from TOUCH Community Services) |

| Enhanced Career Opportunities | “It opens up more career opportunities” (Male, first major in biomedical engineering) | “Public health grads could be familiar with the economics of healthcare services; such expertise could bring additional insights to our work” (Industry stakeholder from Diagnostics Development Hub, Agency for Science and Technology Research) | |

| (b) | |||

| Theme | Subtheme | Illustrative Quote from Graduating Students | Illustrative Quote from Industry Stakeholders |

| Enhancement of Experiential Learning Opportunities | Fieldwork and Industry Exposure | “Perhaps there can be more fieldwork-based courses for students to have more real-world experience with industry professionals through feedback and interactions” (Female, first major in life sciences) | “Graduates have theoretical knowledge but require more practical experience to work independently” (Adjunct faculty and management from Yishun Health and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital) |

| Practical Application Development | “If it is possible, I feel that students can have more exposure to a real public health setting, to experience what public health workers do” (Female, first major in life sciences) | “Their public health knowledge is basic and requires significant supervision in practical settings” (Industry stakeholder from Agency for Integrated Care) | |

| Deepening Specialised Knowledge Domains | Targeted Topical Expertise | “Having more nutrition-related courses to deepen my understanding of dietary public health” (Female, first major in life sciences) | “Graduates need deeper expertise in specialised public health topics to contribute effectively” (Industry stakeholder from Singapore Red Cross) |

| In-Depth Conceptual Understanding | “I would like some courses that address more mental health issues, I took that course and went away gaining a lot of new knowledge, but I can’t help but think that we need to split it up into several courses since one course alone can’t possibly cover all mental health conditions in depth” (Female, first major in biomedical engineering) | “Graduates with a public health minor lack the depth needed for advanced public health roles” (Industry stakeholder from Agency for Integrated Care) | |

| Advancement of Professional Communication and Engagement Skills | Adaptive Communication Strategies | “Public health courses should include more assignments to practise writing and presenting for diverse audiences, rather than relying on exams” (Male, first major in communications and new media) | “Their written communication is often too academic and needs to be more practical for professional settings” (Industry stakeholder from TOUCH Community Service) |

| Effective Stakeholder Collaboration | “More opportunities to work with faculty, industry professionals, and peers would prepare us for collaborating in complex public health settings” (Male, first major in chemistry) | “Graduates need skills in facilitating collaboration in complex, systemic, and political environments” (Adjunct faculty and management from Yishun Health and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lim, R.B.T.; Tan, C.G.L.; Tan, J.R.J.; Sng, P.J.; Teng, C.W.C. Reflective Insights into Undergraduate Public Health Education: Comparing Student and Stakeholder Perceptions. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091201

Lim RBT, Tan CGL, Tan JRJ, Sng PJ, Teng CWC. Reflective Insights into Undergraduate Public Health Education: Comparing Student and Stakeholder Perceptions. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091201

Chicago/Turabian StyleLim, Raymond Boon Tar, Claire Gek Ling Tan, Julian Ryan Jielong Tan, Peng Jing Sng, and Cecilia Woon Chien Teng. 2025. "Reflective Insights into Undergraduate Public Health Education: Comparing Student and Stakeholder Perceptions" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091201

APA StyleLim, R. B. T., Tan, C. G. L., Tan, J. R. J., Sng, P. J., & Teng, C. W. C. (2025). Reflective Insights into Undergraduate Public Health Education: Comparing Student and Stakeholder Perceptions. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1201. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091201