1. Introduction

With technological advancements and the widespread availability of user-friendly and cost-effective devices (e.g., smartphones), new teaching methods that incorporate technology into the educational process have emerged to meet evolving educational demands. Typically, their implementation necessitates robust theoretical guidelines, ensuring that technology is not introduced haphazardly in the classroom but is instead employed in a manner that aligns with pedagogical requirements, students’ needs, and educational objectives; without such grounding, a new teaching methods risk becoming a purely technological shift rather than a meaningful pedagogical transformation (

Bishop & Verleger, 2013). One of these new teaching methods is the flipped learning approach.

Flipped learning has combined instructional guidelines supported by various learning theories. Flipped learning combines constructivist, student-centered learning activities with behaviorist, direct instruction methods, creating a hybrid model that enhances learning opportunities (

Bishop & Verleger, 2013). Flipped learning has been defined in multiple ways. For instance, it is “an educational technique that consists of two parts: interactive group learning activities inside the classroom, and direct computer-based individual instruction outside the classroom” (

Bishop & Verleger, 2013, p. 28). In another study, flipped learning was defined as “the flipped classroom is a pedagogical approach which moves the learning content taught by teachers’ direct instruction to the time before class to increase the chances for the students and teacher to interact. Therefore, teachers would have more time to guide the learning activities and solve students’ problems to promote the learning effects” (

Hwang et al., 2015, p. 452). This practical reorganization of instructional time aligns with several theoretical frameworks that underpin the concept of flipped learning.

There is more than one theoretical framework that supports the pedagogical practice of flipped learning. Flipped classrooms are primarily grounded in student-centered learning theories emphasizing constructivism and social interaction (

Xu & Shi, 2018). Examples of these foundational student-centered learning theories include Piaget’s theory of cognitive conflict (

Piaget, 1967) and Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development (

Vygotsky, 1978), which inform the constructivist foundation of active learning, problem-based learning, and the design of cooperative learning environments. In flipped environments, these three core elements serve various purposes. Problem-based learning enables students to develop flexible knowledge, self-directed learning, and collaboration skills. Active learning would support student engagement through participation, discussion, and reflection. Cooperative learning promotes engagement through structured group tasks that emphasize positive mutual responsibility. Furthermore, Kolb’s experiential learning theory (

Kolb, 2014) has made a significant contribution to informing flipped learning, where experiential learning theory emphasizes learning through experience and reflection, which aligns with the hands-on, interactive nature of flipped classrooms. Similarly,

Felder and Silverman’s (

1988) Learning Styles Model supports flipped learning by focusing on differentiated instruction that addresses individual learning preferences. The model identifies dimensions such as visual and verbal, as well as active and reflective learning. In flipped classrooms, pre-class materials (e.g., videos, readings) can cater to these styles. In-class activities can be designed to match learners’ processing preferences. Previous studies showed that flipped learning was employed in various educational fields that include language education (

Challob, 2021;

Santhanasamy & Yunus, 2022;

Öztürk & Çakıroğlu, 2021), physical education (

Y. N. Lin et al., 2022), engineering education (

Al Mamun et al., 2022), Math education (

Staddon, 2022) teacher education (

Zain et al., 2022), physiology education (

Lu et al., 2023), business and entrepreneurship education (

Senali et al., 2022) medical education (

Phillips & Wiesbauer, 2022) nursing education (

Barranquero-Herbosa et al., 2022). Reflecting on these studies, it is evident that flipped learning is not limited to a specific discipline but offers a versatile pedagogical framework applicable across diverse academic domains. The literature reports several benefits of integrating flipped learning into educational practice. The flipped learning approach had a significant positive effect on vocational learners’ emotions, such as engagement, motivation, self-efficacy, and their cognitive skills, including critical thinking, problem-solving, learning skills, learning strategies, and communicative competence (

Zhou, 2023;

Zain et al., 2022). In addition, compared to lecture-based learning, flipped learning lipped classroom interventions produced positive gains across academic, intra-/interpersonal, and satisfaction-related outcomes in higher education (

Bredow et al., 2021) flipped learning approach has a positive effect on learning, reducing cognitive load, involvement, accuracy, motivation, attitude, and satisfaction with the course and self-efficacy in higher education (

Han, 2022). The literature suggests that flipped learning offers multiple educational benefits, enhancing students’ autonomy, motivation, and performance. It supports emotional engagement and cognitive development, such as critical thinking and problem-solving. Flipping classrooms also improves both academic and interpersonal outcomes. Flipped learning helps reduce cognitive load while increasing student satisfaction and involvement.

In addition, due to the popularity and effectiveness of the flipped learning approach, it has been accompanied by various teaching strategies and technological tools. For instance, studies reported using flipped learning with new generative artificial intelligence e.g., ChatGPT-4 (

Huang et al., 2023;

Gasaymeh & AlMohtadi, 2024) and dynamic mathematics software, e.g., GeoGebra (

Ishartono et al., 2022) In addition, flipped learning was accompanied with Gamified learning platforms to make lessons interactive, increasing student engagement and retention (

Ekici, 2021;

Parra-González et al., 2021) project-based learning (

Hossein-Mohand et al., 2021), Education 4.0 (

Sein-Echaluce et al., 2024) interactive peer-review approach (

H. C. Lin et al., 2021) problem solving approach (

Hsia et al., 2021), online-based teaching (

Tang et al., 2023;

Jia et al., 2023), and Mobile education (

Halili et al., 2021).

The previous discussion highlighted the strong pedagogical foundations of flipped learning, emphasizing that it represents a pedagogical shift supported by technology, rather than a purely technology-driven approach. Additionally, the discussion demonstrated the growing popularity and effectiveness of flipped learning in various fields. Based on researchers’ observations, students in instructional technology-related classes that teach programming often face challenges, particularly since programming is taught in the English language. As a result, flipped learning was introduced to support their understanding. Student satisfaction with new teaching influences several key areas, including student motivation and academic performance, teacher-related outcomes, and institutional recruitment and funding. However, variations in students’ acceptance and satisfaction with the flipped learning approach were observed, indicating a need for further study to understand better students’ acceptance and satisfaction, as well as the factors associated with overall satisfaction with the flipped learning method in instructional technology-related classes.

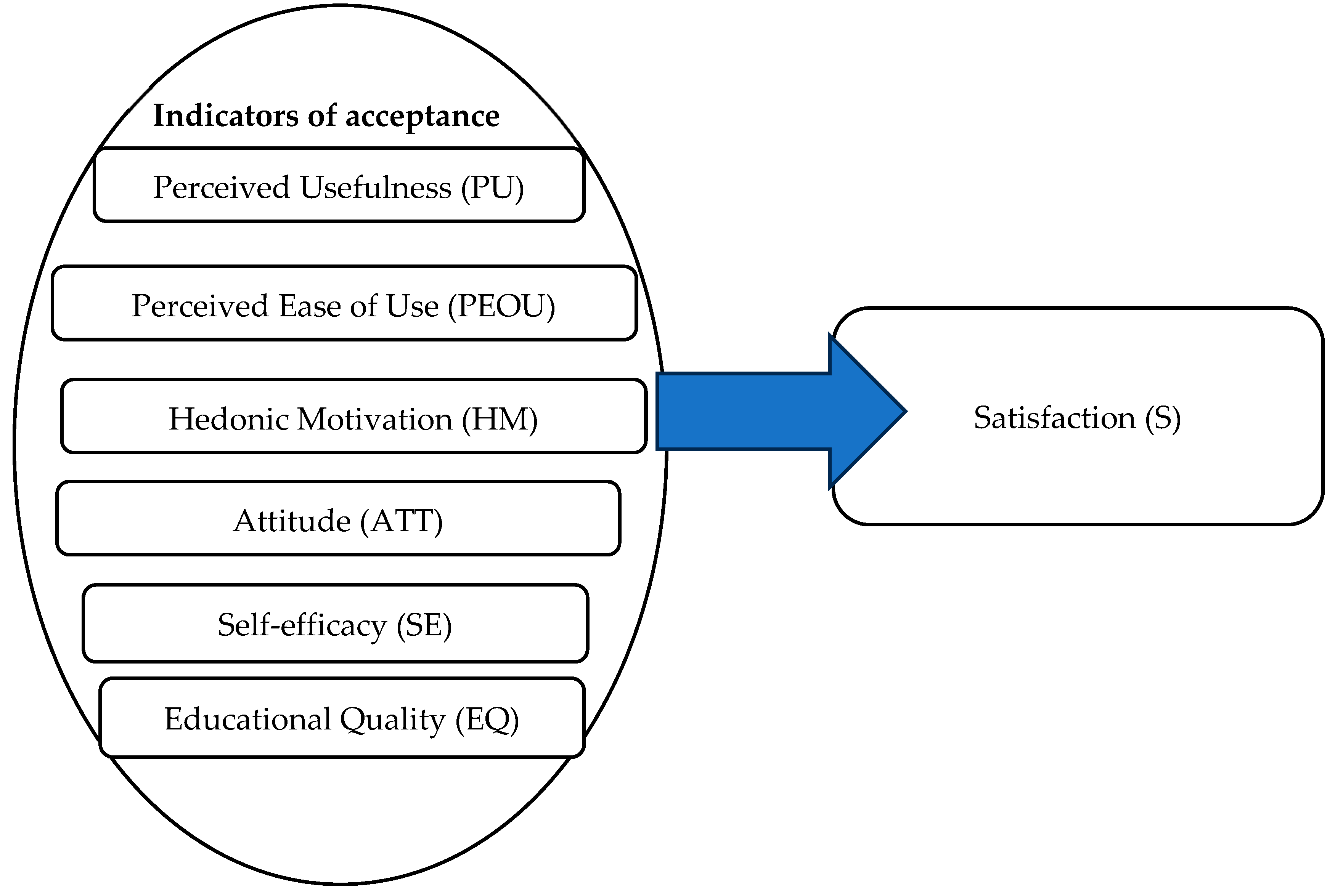

The current study aims to evaluate student acceptance of the flipped learning approach using six indicators—perceived usefulness, ease of use, hedonic motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, and educational quality—and to assess overall satisfaction. Additionally, it examines the relationship between these factors and overall satisfaction with the flipped learning method in instructional technology-related classes. The current study aimed at answering the following research questions:

First research question: How do students perceive the usefulness, ease of use, hedonic motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, and educational quality of the flipped learning approach?

Second research question: How do students perceive their satisfaction with the flipped learning approach?

Third research question: What is the relationship between students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach and the independent variables: perceived usefulness, ease of use, hedonic motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, and educational quality?

Fourth research question: To what extent do perceived usefulness, ease of use, hedonic motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, and educational quality predict students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach?

1.1. Previous Studies

Previous research studies have shown the effectiveness of flipped learning in enhancing different aspects of students’ learning. Various teaching strategies and technological tools accompanied the flipped learning approach. The literature showed that several research studies focused on instructors’ adoption of flipped learning (

Long et al., 2019;

Dalbani et al., 2022;

Yahaya et al., 2022). However, fewer studies focused on students’ acceptance and satisfaction with the flipped classroom.

Some previous research studies focused entirely on examining students’ acceptance and satisfaction with the flipped learning approach. For instance,

Osman et al. (

2023) conducted a study to investigate students’ acceptance of flipped learning in second language acquisition classes. The study employed descriptive research design. The participants were 85 final-year students enrolled in the Bachelor of Arabic Studies program at a university in Malaysia. Data were collected using a structured questionnaire that focused on content design and flipped learning. The results showed high student acceptance, with reflections indicating increased knowledge, improved technological skills, enhanced creative and critical thinking, and positive experiences with group activities.

In a study by

Hoshang et al. (

2021), the researchers investigated university students’ acceptance of the flipped classroom using qualitative and quantitative approaches. Data were collected using various research instruments, including focus group interviews, observations, and mini-structured surveys. There were 300 undergraduate students. The findings indicate a positive student attitude toward flipped learning. The participants believed that flipped learning has the potential to enhance learning outcomes by requiring students to engage with the educational materials.

In Australia,

Fisher et al. (

2015) explored students’ acceptance of the flipped classroom by university students. After experiencing the flipped classroom approach for one semester, data were collected using a questionnaire. The results showed that students preferred the flipped classroom model to traditional face-to-face delivery. The students reported increased engagement, satisfaction, and perceived learning outcomes using flipped learning. On the other hand, the study reported that student satisfaction was initially low, which was attributed to discomfort with the unfamiliar learning structure. Over time, as students adapted, their satisfaction improved significantly. The authors emphasized the importance of supporting students during the initial transition through orientation and digital training to help maximize acceptance and satisfaction early in the learning process.

Furthermore, other existing studies have shown variation in the types of variables that affect students’ acceptance of flipped learning, as well as the intensities of the effect of these variables on students’ acceptance of and behavioral engagement in flipped learning. For instance,

Cai et al. (

2019) explored the relationships between five key factors from a social presence-integrated Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model and students’ adoption of flipped learning. Structural equation modeling was employed to examine the data of 416 Chinese first-year college students. The results showed that facilitating conditions, social presence, and effort expectancy had a significantly positive influence on students’ adoption. Moreover, facilitating conditions and social influence on students’ adoption are mediated by social presence. In a similar study,

Lai et al. (

2021) conducted a study that aimed to empirically test how student-level motivation (i.e., autonomous and controlled), student-level ability (i.e., perceived self-efficacy), and class-level opportunity (i.e., perceived teaching quality and perceived platform quality) influence students’ behavioral engagement in flipped classrooms. Data were collected through a survey completed by 1002 university students. The results revealed that autonomous motivation, controlled motivation, perceived self-efficacy, and perceived teaching quality were critical determinants of university students’ behavioral engagement in flipped classrooms. The positive relationship between autonomous motivation and behavioral engagement became stronger when perceived self-efficacy was high. Moreover, when perceived platform quality was high, the positive relationship between autonomous motivation and behavioral engagement became stronger. In addition, when perceived platform quality was low, the negative relationship between controlled motivation and behavioral engagement became stronger. Follow-up interviews with the students emphasized five contradictions in flipped classrooms that hindered behavioral engagement. There was tension between types of learning, the videos were boring, not all students participated in the discussions, students lacked sufficient time for in-class activities, and teachers did not have good interaction skills.

In another study conducted with medical students,

Abdekhoda et al. (

2020) explored the factors influencing the adoption of the flipped classroom approach among university students using an extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). The data was collected using a questionnaire completed by 110 medical students at a university in Iran. The data showed that subjective norms and perceived enjoyment have a direct and significant effect on perceived usefulness of the flipped classroom approach. Additionally, the study found that perceived usefulness, ease of use, and self-efficacy had a direct and significant impact on the adoption of the flipped classroom.

In a similar study that focused on students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach,

Samaila et al. (

2021) investigated the factors influencing college of education students’ satisfaction with the flipped classroom. The data were collected from 110 students using a questionnaire instrument. The examined factors were instructor-generated video content, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and perceived value. The findings showed that perceived value had a positive impact on students’ satisfaction with the flipped classroom model. However, the findings showed that instructor-generated video content, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use did not significantly influence students’ satisfaction.

In a study examining the impact of e-learning readiness on students’ satisfaction and motivation in a flipped learning setting,

Yilmaz (

2017) investigated how various aspects of e-learning readiness influence students’ experiences. Data were collected from 236 undergraduate students using a quantitative research instrument with multiple dimensions to measure students’ readiness for e-learning, satisfaction, and motivation strategies. The dimension that was intended to measure their readiness for e-learning consisted of six sub-scales: computer self-efficacy, internet self-efficacy, online communication self-efficacy, self-directed learning, learner control, and motivation towards e-learning. The findings indicated that e-learning readiness significantly predicted student satisfaction and motivation in the flipped classroom model. The findings highlighted the importance of digital preparedness for effective participation in flipped learning environments.

In another study examining factors influencing students’ satisfaction and engagement with the flipped classroom in private universities in China,

Guan (

2024) investigated the relationships between perceived quality, perceived value, student interactions, teaching process, instructional content, student satisfaction, and student engagement. Data were collected from 500 students using a questionnaire. The findings revealed that perceived quality, value, teaching process, and student interaction had a significant impact on student satisfaction, which in turn strongly affected student engagement. The teaching process had a significant influence on satisfaction and engagement, while instructional content had a minimal impact on the usage of the flipped classroom.

Previous studies examining students’ perceptions and satisfaction with the flipped learning approach have shown variations in the findings. Most examined studies demonstrate high student acceptance and satisfaction with the flipped learning approach. Students expressed positive perceptions regarding their learning experiences, highlighting increased motivation, engagement, and perceived effectiveness. However, some studies have shown that students may initially have low satisfaction with flipped learning due to unfamiliarity. Furthermore, studies examining the factors that affect students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach have shown that students perceive flipped learning to be influenced by a combination of technological, motivational, and contextual factors. The participants reported that key elements supporting their adoption of flipped learning included: the presence of facilitating conditions, a strong sense of social presence, and clear expectations of the effort required. They also emphasized the importance of autonomous and controlled motivation, perceived self-efficacy, and teaching quality in enhancing engagement. Additionally, students noted that perceived usefulness, ease of use, and e-learning readiness—particularly self-directed learning and communication self-efficacy—positively affected their satisfaction. The studies showed that external influences such as social norms and perceived value, primarily when mediated by social presence or perceived usefulness, contributed meaningfully to their acceptance of flipped learning. While some factors, such as instructor-generated content and instructional materials, were perceived as less impactful, others, including the teaching process, student interaction, and the overall value of the flipped learning experience, had a notable effect on satisfaction and engagement.

The inconsistencies in findings from previous studies as well as the shortage of studies that addressed the flipped learning in educational systems, in which traditional teacher-centered methods dominate, e.g., Jordanian educational, highlights the need for more nuanced investigations that consider transitional challenges within culture-specific learning environments, where students may be less familiar with technology-driven instructional models.

1.2. Theoretical Framework

Based on the previous discussions, the current study adopted three types of factors that may affect student satisfaction with flipped learning. These factors can be categorized into technology-related beliefs, user-centered motivational, and contextual factors. Technology-related beliefs include perceived usefulness and ease of use (

Abdekhoda et al., 2020;

Samaila et al., 2021), while user-centered motivational factors encompass intrinsic motivation, attitude toward flipped learning, and self-efficacy (

Lai et al., 2021;

Yilmaz, 2017). The contextual factor is educational quality (

Guan, 2024).

Perceived usefulness of flipped learning measures to which students believe that the approach improves their academic performance by deepening their understanding of course materials, boosting their grades, and providing a more engaging and enriching learning experience than traditional methods. Ease of use of the flipped learning approach measures the extent to which students find the approach user-friendly and straightforward. It reflects that flipped learning does not require complex skills, demands less effort compared to traditional learning, and offers platforms and resources (such as videos) that are easy to use and access. Perceived usefulness and ease of use represent the primary constructs of the TAM model (

F. Davis, 1986), the TAM2 model (

Venkatesh & Davis, 2000), and the UTAUT model (

Venkatesh et al., 2003).

Hedonic motivation in flipped learning refers to the extent to which students find the method enjoyable and comfortable. It reflects that students enjoy participating in flipped learning activities, feel at ease when using the approach, and look forward to engaging with it because it consistently provides enjoyable learning experiences. Hedonic motivation represents one of the primary constructs of the UTAUT2 model (

Venkatesh et al., 2012).

Attitude in flipped learning reflects the students’ overall evaluation of this instructional approach. It suggests that they perceive flipped learning as a practical educational approach that enhances their academic performance and overall learning experience. Students with a positive attitude believe that flipped learning improves their academic outcomes and prefer it over traditional methods for acquiring knowledge and skills. Attitudes represent a central construct in several technology acceptance models such as the TAM model (

F. Davis, 1986), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (

Ajzen, 1991).

Self-efficacy in flipped learning refers to students’ confidence in their ability to understand and apply the concepts taught through this approach. It encompasses their belief that they can succeed academically, overcome challenges, and achieve their educational goals using flipped learning methods. Self-efficacy constitutes a fundamental construct of Social Cognitive Theory (

Bandura, 1977,

1986); it may play a central role in shaping users’ confidence and intention to engage with technology.

Educational quality in flipped learning refers to the extent to which students perceive the educational content as high-quality and relevant to their studies. It reflects their belief that flipped learning effectively delivers materials, enhances understanding of complex topics, and helps them grasp the subject matter comprehensively. Educational quality was used in several research studies as a factor that would shape students’ satisfaction and engagement with educational systems (

Al-Fraihat et al., 2020;

Lai et al., 2021).

On the other hand, students’ satisfaction was measured using one scale. Satisfaction in flipped learning measures students’ overall contentment with their experience. It reflects their approval of the learning process, the outcomes they achieve, and the overall benefits of engaging with the flipped learning method.

Figure 1 illustrates the adopted model guiding the current investigation.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Method

This study utilized a descriptive cross-sectional research design with an exploratory and correlational orientation. The descriptive cross-sectional research design is suitable for exploring current research topics, such as college of education students’ acceptance of and satisfaction with the flipped learning approach, and how acceptance factors are related to and associated with overall satisfaction with the flipped learning method in an instructional technology-related class. In this research, the descriptive design enables a thorough exploration of students’ acceptance of and satisfaction with the flipped learning approach by offering a detailed snapshot of the current situation without altering any variables (

Aron et al., 2005). This design helps answer questions about the extent of acceptance and satisfaction among students. The correlational aspect of this study aimed to identify the relationships between key independent variables, including perceived usefulness, ease of use, hedonic motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, and educational quality, and the dependent variable, which is students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach.

Data were collected using a questionnaire instrument. The following section presents research questions, participant information, details about the research instrument, and the steps taken in the study.

2.2. Participants

The target population for this study included undergraduate students enrolled in the “Computer Applications in Education” course offered by the College of Education over three consecutive semesters: the second semester of the 2023/2024 academic year, and the first and second semesters of 2024/2025. All students in this course experienced the flipped learning model as part of their instructional activities. The number of these students was 180. The study sample consisted of 137 students from the population who agreed to participate in the current study and voluntarily completed the questionnaire. Due to the limited number of the target population, all the students were invited to participate in the current study.

The questionnaire instrument collected demographic data on the participants, including their gender, age, major, and academic year (

Table 1). One hundred thirty-seven students completed the questionnaire for the study.

Most participants (94.9%, n = 130) were female, while only a small portion (5.1%, n = 7) were male. In terms of majors, 39.4% (n = 54) were enrolled in teacher education, 32.8% (n = 45) in special education, and 27.7% (n = 38) in kindergarten education. Most participants (81.8%, n = 112) were between the ages of 21 and 25. A smaller group (13.9%, n = 19) was aged 18 to 20, while only a few were between 26 and 30 (2.9%, n = 4) or older than 30 (1.5%, n = 2). Regarding the academic year, over half of the participants (51.8%, n = 71) were third-year students, followed by 38.7% (n = 53) in their fourth year. A smaller number were in their second year (8.0%, n = 11), and very few were first-year students (1.5%, n = 2).

2.3. Research Instrument

The current study’s research instrument was a questionnaire with eight sections. The first section aims to collect information regarding participants’ demographic characteristics, including gender, age, major, and academic year. The remaining sections collected data regarding students’ perceptions of flipped learning across several dimensions, including Perceived Usefulness (PU), Perceived Ease of Use (PEOU), Hedonic Motivation (HM), Attitude (ATT), Self-Efficacy (SE), Educational Quality (EQ), and Satisfaction (S). The questionnaire comprised 21 items, with three items allocated to each dimension. The questionnaire instrument was developed based on a review of previous studies (

Bandura & Wessels, 1997;

Venkatesh et al., 2003;

Akçayır & Akçayır, 2018;

Cai et al., 2019;

Tamilmani et al., 2019;

Yahaya et al., 2022). The response options used in these seven scales consisted of a five-point Likert scale, with each numerical value corresponding to a distinct level of agreement. Specifically, “1” represented “Strongly Disagree,” “2” implied “Disagree,” “3” signified “Neutral,” “4” indicated “Agree,” and “5” mirrored “Strongly Agree.”

Face validity was assessed by experts in educational technology and curriculum and instruction, who reviewed the questionnaire to ensure it appears to measure what it is intended to measure. In addition, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principal component extraction and Varimax rotation was conducted on the 21 questionnaire items. The KMO value was 0.935, and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (

p < 0.001), indicating the data was suitable for factor analysis. Two components were extracted based on eigenvalues greater than 1, explaining a cumulative 57.6% of the total variance. Items loaded meaningfully onto two factors, with some overlap across constructs. Factor 1 captured items related to perceived usefulness, self-efficacy, and attitudes, while Factor 2 included ease of use, hedonic motivation, support, and educational quality. Some items showed cross-loading (e.g., SE1, ATT2) but were retained based on theoretical relevance. The results suggest that students’ perceptions of flipped learning cluster into broader dimensions. These findings support the questionnaire’s construct validity while indicating that learners may view flipped learning experiences in more integrated ways than suggested by separate theoretical dimensions.

Table 2 shows the rotated component matrix for the 21 questionnaire items.

Cronbach’s Alpha values were used to examine the reliability of the questionnaire’s sub-scales for data collection. The results showed that the values of Cronbach’s Alpha for the dimensions ranged between 0.64 and 0.91 (See

Table 3). In the social and behavioral sciences, a reliable measure typically has a Cronbach’s Alpha of at least 0.6 or 0.7, with values approaching 0.9 being preferable (

Aron et al., 2005), making the data collection tool a suitable measure of university students’ acceptance and satisfaction with the flipped learning approach.

2.4. Study Context and Implementation

The study was conducted over three consecutive semesters with students enrolled in a course titled “Computer Applications in Education.” These semesters included the second semester of the 2023/2024 academic year and the first and second semesters of the 2024/2025 academic year. During these classes, students experienced a flipped learning approach. Prior to class meetings, students were provided with pre-recorded video lectures and digital readings through the university’s learning management system (Microsoft Teams). These materials aimed to introduce Foundational concepts and skills. During in-class sessions, students engaged in interactive activities that included guided discussions and hands-on software exercises. The in-class activities were conducted under the instructor’s supervision.

2.5. Data Collection and Analysis Procedures

Data collection took place after students had completed their experience with flipped learning. The data was collected electronically through a link to the questionnaire posted on Microsoft Teams, the learning management system used in the course. Participation in the study was voluntary, and no personal information was collected from participants. The data collected were reviewed prior to statistical analysis. Descriptive analyses were conducted to answer the first and second research questions, using means and standard deviations to summarize and quantify students’ responses to the questionnaire. Univariate correlations were used to assess and quantify the relationships between students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach and key independent variables, including perceived usefulness, ease of use, hedonic motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, and educational quality to address the third research question. Multiple regression analysis was employed to address the fourth research question: whether perceived usefulness, ease of use, hedonic motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, and educational quality are significantly associated with students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach. Data analysis was conducted using SPSS 15.0 software.

3. Results

3.1. First Research Question: How Do Students Perceive the Usefulness, Ease of Use, Hedonic Motivation, Attitude, Self-Efficacy, and Educational Quality of the Flipped Learning Approach?

Students’ acceptance of flipped learning approach were measured through six dimension that include their perception of the usefulness of flipped learning approach, their perceptions of the ease of use flipped learning approach requirements, their drive to engage in flipped learning approach measured in hedonic motivation scale, their attitude toward learning through flipped learning approach, their perceived self-efficacy in succeeding through flipped learning, and their perceptions of the educational quality of flipped learning approach. In addition, students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach was measured through one dimension. Students’ perceptions and satisfaction with the flipped learning approach were categorized into three categories: low (1.00–2.33), moderate (2.34–3.66), and high (3.67–5.00). Students’ perceptions and satisfaction with the flipped learning approach were categorized into low, medium, and high categories using fixed interval categorization.

Students’ perceptions of the various aspects of the flipped learning approach were generally positive, with levels ranging from moderate to high. Four out of six scales scored at a high level, with close values. In descending order, they were: their hedonic motivation to use flipped learning approach scale (M = 3.73, SD = 0.97), their attitude toward learning through flipped learning approach scale (M = 3.71, SD = 0.93), their perceptions of the educational quality of flipped learning approach scale (M = 3.71, SD = 0.97) and the overall mean score of the students’ perceptions of the ease of using flipped learning approach scale (M = 3.67, SD = 0.93). These findings indicate general favorable agreement in perceptions across the measured aspects of the flipped learning approach. Students’ responses to the hedonic motivation scale reflect students’ enjoyment, entertainment, and sense of convenience when using this approach. Students’ similar responses to attitude toward learning through the flipped learning approach and perceptions of its educational quality were rated nearly as high, implying that students enjoyed the approach and recognized its effectiveness in enhancing their learning experience. Students’ perceptions of the ease of using the flipped learning approach scored slightly lower than the other three highly rated scales, but still at a high level, suggesting that while students found the approach user-friendly, some aspects may require further support to enhance usability.

Regarding the other two scales, the overall mean score on the Self-Efficacy Scale was 3.64 with a standard deviation of 1.06, while the overall mean score on the Perceived Usefulness Scale was 3.59 with a standard deviation of 0.96. The findings suggest that students perceived flipped learning as a moderately valuable teaching approach and have moderate confidence in their ability to succeed in learning through this approach. However, the considerable standard deviation value for the Self-efficacy Scale indicates considerable variability in the responses.

Table 4 shows the means, standard deviations, and levels of students’ responses to the six-scale components regarding their acceptance of the flipped learning approach.

3.2. Second Research Question: To What Extent Are Students Satisfied with the Flipped Learning Approach?

The overall mean score on the Satisfaction Scale was 3.58, with a standard deviation of 0.98, indicating that students had a moderate level of satisfaction with flipped learning, with considerable variability in their responses.

3.3. Third Research Question: What Is the Relationship Between Students’ Satisfaction with the Flipped Learning Approach and the Independent Variables: Perceived Usefulness, Ease of Use, Hedonic Motivation, Attitude, Self-Efficacy, and Educational Quality?

This section addresses the third research question regarding the relationship between students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach and the main independent variables of this study: (a) perceived usefulness, (b) perceived ease of use, (c) hedonic motivation, (d) attitude, (e) self-efficacy perceived value, and (f) educational quality. The Pearson Product Moment correlation coefficients were used to represent the relationship between students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach and the main independent variables of this study: (a) perceived usefulness, (b) perceived ease of use, (c) hedonic motivation, (d) attitude, and (e) self-efficacy, and (f) educational quality. To provide a qualitative description of the Correlation coefficients,

J. Davis’s (

1971) descriptors were employed to assign (negligible = 0.00 to 0.09; low = 0.10 to 0.29; moderate = 0.30 to 0.49; substantial = 0.50 to 0.69; very strong = 0.70 to 1.00).

Table 5 presents the correlation matrix, which illustrates the relationship between satisfaction and the independent variables.

The results showed that there were robust positive correlation between students’ satisfaction of flipped learning approach and four independent variables that were hedonic motivation (r = 0.75, p < 0.01), attitude (r = 0.74, p < 0.01), self-efficacy (r = 0.75, p < 0.01), and educational quality (r = 0.74, p < 0.01). Substantial positive correlation were found between students’ satisfaction of flipped learning approach and two independent variables that were perceived usefulness (r = 0.64, p < 0.01) perceived ease of use (r = 0.61, p < 0.01).

However, while correlations indicate a relationship between each independent variable and satisfaction, they do not reveal the unique contribution of each factor when all variables are considered simultaneously. Therefore, regression analysis becomes essential. By employing regression, the extent to which each independent variable is associated with students’ satisfaction while controlling for the association of the others can be assessed.

3.4. Fourth Research Question: To What Extent Do Perceived Usefulness, Ease of Use, Hedonic Motivation, Attitude, Self-Efficacy, and Educational Quality Predict Students’ Satisfaction with the Flipped Learning Approach?

Multiple regression analysis was conducted to answer this research question. Prior to the analysis, the assumption of multicollinearity among the independent variables was examined using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). All VIF values ranged between 2.17 and 3.09, which are well below the commonly accepted threshold of 5, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern. Additionally, the assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity were assessed. The scatterplot of standardized residuals versus predicted values displayed a random pattern, supporting the assumption of homoscedasticity. The histogram and normal P–P plot indicated that the residuals were approximately normally distributed. Furthermore, the Durbin–Watson statistic was 2.103, which falls within the acceptable range of 1.5 to 2.5, indicating that the residuals are independent. These results support the validity of the regression assumptions.

To answer the fourth research question, multiple regression analysis was conducted to determine how perceived usefulness, ease of use, hedonic motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, and educational quality are related to students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach. A direct method entry was used for the multiple linear regression analyses. The results showed that 71% of the variance in Students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach was explained by the independent variables included in this study. 71% represents the value of the adjusted R-squared (R2), which represents the population R2 that can be used to generalize the findings from the sample.

The test statistics were significant at the 0.05 significance level (F(6, 130) = 55.38;

p < 0.00).

Table 6 and

Table 7 summarize the results of the multiple regression analysis.

The Regression Coefficients of the Standard Regression Model were calculated to examine the contribution of each independent variable in association with the dependent variable (

Table 8). For the first and second independent variables (perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use), the tests were not statistically significant (t = −0.48, Β = −0.04;

p = 0.63) and (t = 0.17, Β = 0.01;

p = 0.87), respectively. This suggested that students’ perceptions of the usefulness and ease of use of the flipped learning approach were not significantly associated with their satisfaction with the approach when considered alongside other variables. Students’ perceptions of the usefulness and ease of using the flipped learning approach had a significant positive correlation with the dependent variable (students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach). However, this relationship was insignificant when examined in the context of other independent variables, such as group. The other four independent variables were statistically significant. For instance, the students’ hedonic motivation variable was statistically significantly associated with their satisfaction with the flipped learning approach (t = 3.47, Β = 0.28;

p = 0.001) when considered alongside other variables. The students’ attitude variable was statistically significantly associated with their satisfaction with the flipped learning approach (t = 2.49, Β = 0.20;

p = 0.01) when considered alongside other variables. The students’ self-efficacy variable was statistically significantly associated with their satisfaction with the flipped learning approach (t = 3.96, Β = 0.31;

p = 0.00). Students’ perception of the educational quality variable was statistically significantly associated with their satisfaction with the flipped learning approach (t = 2.45, Β = 0.20;

p = 0.016).

4. Discussion

The findings indicate that students generally view the flipped learning approach positively. Their perception reflects that the method is beneficial, manageable, enjoyable, and educationally sound. At the same time, there are noticeable variations in how confidently students feel about their ability to succeed using this approach. The findings reveal a notable difference between the highest-and lowest-rated dimensions of students’ perceptions of the flipped learning approach, where hedonic motivation received the highest mean score, indicating that students found the approach intrinsically rewarding. A possible explanation of such results might be attributed to its flexibility as well as its learner-centered nature. In contrast, perceived usefulness scored the lowest, suggesting that while students were emotionally engaged, they were less convinced of the approach’s effectiveness in enhancing academic outcomes. This suggests that while many students adapt well to the flipped classroom, others may experience uncertainty in fully embracing the new learning approach. In addition, the gap between hedonic motivation and perceived usefulness suggests that flipped learning may succeed in fostering students’ motivation. However, it requires more explicit alignment with learning objectives to strengthen its perceived academic value. The findings align with the findings of previous studies (

Osman et al., 2023).

Regarding students’ satisfaction with flipped learning, the findings point to a moderate level of student satisfaction with flipped learning, accompanied by noticeable variation in perceptions. The results indicate that while students see value in the flipped learning approach, their responses vary significantly. Some students appreciate the method, which allows them to be active learners, while others may find it less effective. This variability suggests that the flipped classroom model may not uniformly accommodate all learning preferences, highlighting potential areas for refinement. Given these findings, examining the factors influencing student satisfaction with the flipped learning approach becomes essential. A possible explanation of the moderate level of satisfaction with flipped learning in this study is due to the fact reported by

Fisher et al. (

2015), who found that student satisfaction usually becomes initially low due to discomfort with unfamiliar learning structures; however, it is expected to increase over time. The finding regarding the relationship between students’ satisfaction and the six independent variables suggest that students who find the learning process enjoyable, hold positive attitudes, feel confident in their abilities, and perceive the educational quality as high tend to report greater satisfaction. In addition, these findings suggest that when students recognize the practical benefits of the flipped learning approach and find it easy to engage, their overall satisfaction with the approach increases. Together, these results underscore the importance of both the intrinsic enjoyment and quality of the educational experience, as well as the practical aspects that make the approach effective.

The regression analysis revealed that while students’ positive views on the usefulness and ease of engaging with the flipped learning approach initially appeared related to satisfaction, these factors did not uniquely associate with satisfaction when other variables were considered. While TAM posits that perceived usefulness (PU) and perceived ease of use (PEOU) are core determinants of individuals’ attitudes and intentions toward using technology (

F. Davis, 1986), their predictive strength appears to diminish when considered alongside contextual variables such as enjoyment, confidence, and quality perceptions. The analysis highlighted that the enjoyment students experienced, their overall positive attitudes, confidence in their ability to learn effectively, and the perceived quality of the educational experience were the most influential contributors to their satisfaction with the flipped learning approach. One possible explanation is that

perceived educational quality captures broader contextual factors such as instructional design and learning outcomes and that may subsume or outweigh the influence of PU and PEOU.

The findings aligned with those of previous studies, such as

Samaila et al.’s (

2021) study, which showed that perceived usefulness and ease of use did not significantly associate with students’ satisfaction when considered alongside other variables. In addition, the findings regarding the significance of the perceived quality of the educational experience in association with students’ satisfaction with the flipped learning approach align with those of

Guan’s (

2024) study, which showed that the perceived quality of the educational experience significantly impacted student satisfaction.

5. Conclusions

The study offers valuable insights into students’ acceptance and satisfaction with the flipped learning approach. Overall perceptions were moderately to highly positive, with the highest ratings for hedonic motivation, attitude, and educational quality, and lower ratings for self-efficacy and perceived usefulness. While satisfaction was moderate, all six variables showed significant positive correlations with it. Regression analysis revealed that hedonic motivation, attitude, self-efficacy, and educational quality were significantly associated with satisfaction when considered in conjunction with other variables.

These results suggest that a well-designed and effectively implemented flipped learning approach can offer students an enjoyable and meaningful learning experience. In addition, the results suggested that participants felt less confident in their ability to succeed with flipped learning and expressed some doubt about its benefits compared to traditional instructional methods. The results indicate that Technology-related beliefs, including perceived usefulness and ease of use, are less prominent in shaping students’ overall experience. These findings highlight that students’ enjoyment, emotional response, confidence, and judgment of educational value are central to their satisfaction with flipped learning, rather than the approach’s perceived practicality or technical simplicity.

5.1. Recommendations for Practice

The current study provides information that faculty members can consider as they plan to introduce flipped learning into their educational practice. First, faculty members should consider hedonic motivation when designing flipped learning activities, as it is one of the strongest predictors of satisfaction. This can be achieved by making the flipped learning experience engaging, interactive, and enjoyable. As they can increase students’ intrinsic interest in the content, faculty members can incorporate gamification, multimedia storytelling, real-world case studies, and opportunities for creative expression into a flipped learning approach. Second, faculty members should foster students’ positive attitudes toward flipped learning by helping them understand the rationale behind using this approach. Third, faculty members should strengthen students’ self-efficacy by adopting encouraging educational strategies, including scaffolded learning experiences, timely feedback, and peer collaboration. Additionally, faculty members should offer extra instructional support to students who initially struggle with the independent components of flipped learning. Fourth, faculty members should provide high-quality educational content through video lectures, clear instructions, and well-structured active learning sessions. Additionally, they should ensure that pre-class materials and in-class activities are well-aligned. Finally, although ease of use and perceived usefulness were not significant predictors of satisfaction in the regression model, they remain important factors for adoption. Therefore, faculty members should provide students with user-friendly learning management systems, straightforward navigation, and technical support in the flipped learning approach. Educators are also encouraged to continuously monitor student feedback and make iterative adjustments to improve their learning experience.

5.2. Recommendations for Future Research

Future studies can build upon and extend the current study’s findings to understand further the issues related to implementing the flipped learning approach. The following recommendations were made based on the findings of this study. First, future studies should consider various research designs and methods better to understand students’ experiences with the flipped learning approach. For instance, future studies should consider longitudinal research designs to investigate how students’ perceptions evolve with continued exposure to the flipped learning approach. In addition, future studies should consider employing qualitative research methods that utilize qualitative data collection tools, such as interviews and observations. Moreover, such qualitative data can complement quantitative findings and help better understand what contributes to students’ satisfaction in the flipped learning approach. Additionally, a quasi-experimental design comparing flipped learning with other traditional instructional models can help identify the specific strengths and weaknesses of these models. Second, to enhance the generalizability of the findings, research can explore flipped learning across different disciplines, educational levels, and institutional contexts. Third, future research should examine how students’ demographic characteristics, such as prior academic achievement, learning styles, digital literacy, motivation levels, and cultural background, influence their perceptions and satisfaction with flipped learning. Fourth, future research should consider examining whether instructor differences moderate satisfaction outcomes.

5.3. Limitations

The study employed a descriptive cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to make causal inferences. While statistical associations between variables were identified, longitudinal or experimental research would be needed to establish predictive relationships over time.

One notable limitation of the study lies in its limited external validity. The research was conducted within a single undergraduate course across three consecutive semesters from a single institution, with a relatively small sample size (N = 137) and a highly skewed gender distribution (95% female). This demographic imbalance, combined with the disciplinary homogeneity of the participants, may restrict the generalizability of the findings.

In addition, the use of self-report questionnaires might increase the possibility of self-report bias, which could affect the accuracy of the measured variables and the relationships among them. Adding to that, the course was taught by the same instructor for all participants, which may have created instructor-specific effects on students’ perceptions and satisfaction.