A Systematic Instructional Approach to Teaching Finance Vocabulary to Students with Moderate-to-Significant Disabilities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Would the systematic instructional approach for presenting a short-duration lesson prove to be effective in teaching participants with moderate-to-significant disabilities to read six finance vocabulary words?

- Would the approach prove to be effective in teaching participants with moderate-to-significant disabilities to identify the definitions for the six finance vocabulary words after the participants learned to read them?

- Would the participants maintain their abilities to read the words and identify their definitions for up to four weeks?

- Would the participants read the finance vocabulary and identify each term’s definition across different materials and conditions?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

- high levels of attendance (i.e., were in attendance more than 90% of the days school was scheduled to be in session);

- the ability to participate in a tabletop lesson for 15 min;

- low-level/stable performance of the targeted skill during baseline probes;

- visual and auditory acuity within normal limits; and

- the propensity to imitate a combination model/verbal/gestural/physical prompt.

2.2. Setting

2.3. Design

- The participant must read the word aloud.

- The instructor and participant discuss a participant-friendly definition for the word.

- The instructor presents a concrete, pictorial, or verbal/written example of the word’s definition. If necessary, the instructor presents non-examples in the same manner.

- The instructor conducts a check for understanding.

2.4. Probes

- The teacher held up a graphic and placed four vocabulary words printed on four separate index cards in a row in front of the participant. The teacher directed the participant to touch the word whose definition was represented by the graphic.

- The teacher held up an index card with a word printed on it and placed four graphics printed on four separate cards in a row in front of the participant. Additionally, a printed definition that was presented on an index card that had been cut in half horizontally was read by the teacher and then placed above its corresponding graphic. The teacher directed the participant to touch the graphic/printed definition pair for the word.

- The teacher held up a printed definition on an index card that had been cut in half horizontally, read it, and then placed four vocabulary words printed on four separate index cards in a row in front of the participant. The teacher directed the participant to touch the word for the definition that was presented.

- The teacher held up an index card with a word printed on it and placed four printed definitions on index cards that had been cut in half horizontally in a row in front of the participant. The teacher read each definition and then directed the participant to touch the printed definition for the word.

2.5. Independent and Dependent Variables

2.6. Reliability

2.6.1. Interobserver Agreement

2.6.2. Procedural Fidelity

3. Results

3.1. Acquisition, Maintenance, Generalization, Social Validity

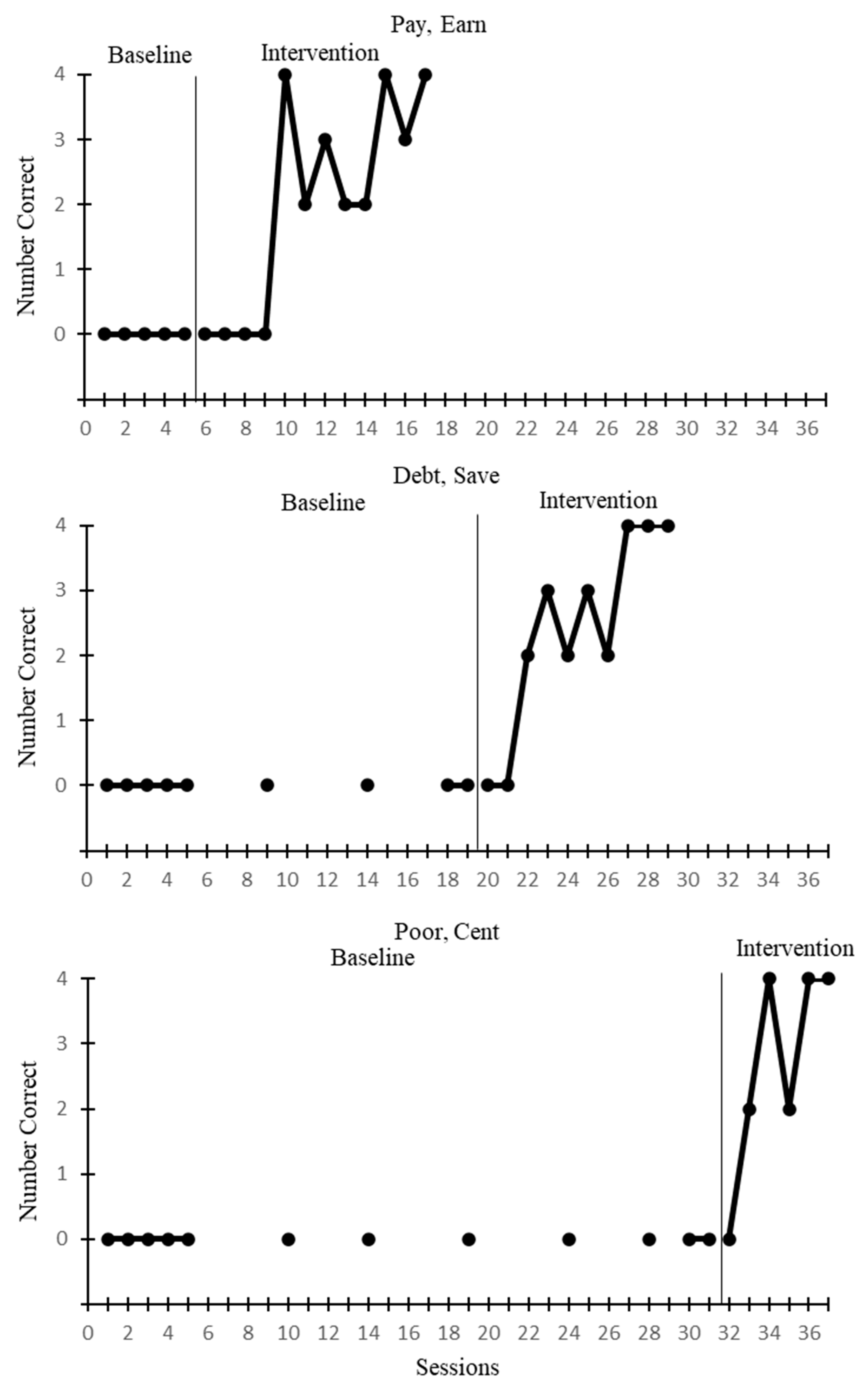

3.1.1. Acquisition

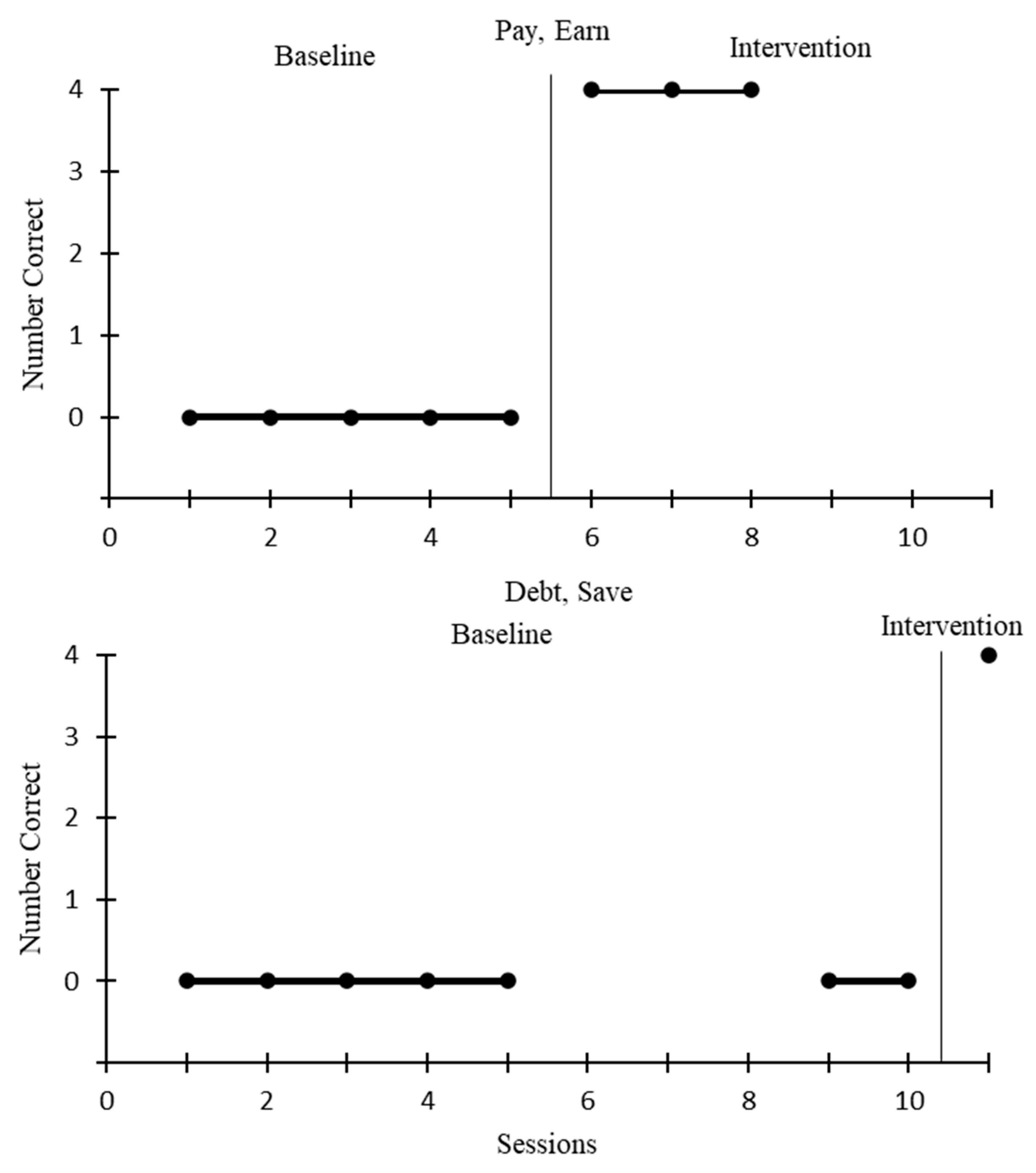

3.1.2. Maintenance and Generalization

3.1.3. Social Validity

4. Discussion

- validating the systematic instructional approach’s effectiveness in teaching other academic content;

- assessing instructional efficiency parameters (e.g., trials, sessions, and total time to criterion, plus the amount of targeted content and incidental information learned);

- determining the merits of including the different elements of explicit instruction;

- comparing complimentary response prompting strategies, and their ordering in a lesson; and

- obtaining fidelity of implementation and social validity data for evaluating the relative ease and difficulty involved with executing this intervention.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IDEA | Individuals with Disabilities Education Act |

| MTSS | Multi-tier system of supports |

References

- Archer, A. L. (2021, October 20). Dynamic vocabulary instruction part 1: Increasing the academic vocabulary of elementary students [Webinar]. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3moaa5cyQKM (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. A. (2011). Explicit instruction: Effective and efficient teaching. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Browder, D. M., Ahlgrim-Delzell, L., Spooner, F., Mims, P. J., & Baker, J. N. (2009). Using time delay to teach literacy to students with severe developmental disabilities. Exceptional Children, 75(3), 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capin, P., Stevens, E. A., Stewart, A. A., Swanson, E., & Vaughn, S. (2021). Examining vocabulary, reading comprehension, and content knowledge instruction during fourth grade social studies teaching. Reading & Writing, 34(5), 1143–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodura, S., Kuhn, J.-T., & Holling, H. (2015). Interventions for children with mathematical difficulties: A meta-analysis. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie, 223(2), 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciullo, S., Lo, Y.-L. S., Wanzek, J., & Reed, D. K. (2016). A synthesis of research on informational text reading interventions for elementary students with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 49(3), 257–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, M. B., MacLauchlan, M. P., Cihak, D. F., Martin, M. S., & Wolbers, K. (2015). Comparing teacher-provided and computer-assisted simultaneous prompting for vocabulary development with students who are deaf or hard of hearing. Journal of Special Education Technology, 30(3), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B. C. (2012). Systematic instruction for students with moderate and severe disabilities. Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, A. W., Brock, M. E., Odom, S. L., Rogers, S. J., Sullivan, L. H., Tuchman-Ginsberg, L., Franzone, E. L., Szidon, K., & Collet-Klingenberg, L. (2013). National Professional Development Center on ASD: An emerging national education strategy. In P. Doehring (Ed.), Autism services across America: Road maps for improving state and national education, research, and training programs (pp. 249–266). Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds, R. Z., Powell, S., & Kearns, D. (2019). To be clear: What every educator needs to know about explicit instruction [Webinar]. National Center on Intensive Intervention. Available online: https://intensiveintervention.org/resource/What-Every-Educator-Needs-to-Know-About-Explicit-Instruction (accessed on 19 February 2019).

- Education Research Reading Room. (2021). Anita Archer on explicit instruction [Audio podcast]. Available online: https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/errr-060-anita-archer-on-explicit-instruction/id1200068608?i=1000543590958 (accessed on 29 April 2025).

- Gast, D. L., & Ledford, J. R. (Eds.). (2014). Single case research methodology: Applications in special education and behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gersten, R., Compton, D., Connor, C. M., Dimino, J., Santoro, L., Linan-Thompson, S., & Tilly, W. D. (2008). Assisting students struggling with reading: Response to intervention and multi-tier intervention for reading in the primary grades. A practice guide (NCEE 2009-4045). U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/Docs/PracticeGuide/rti_reading_pg_021809.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Graham, S., McKeown, D., Kiuhara, S., & Harris, K. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of writing instruction in the elementary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(4), 879–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groshell, Z. (2024). Just tell them: The power of explanations and explicit teaching. John Catt. [Google Scholar]

- Harlacher, J. D. (2023, December 14). If you’ve got a problem, ICE-L will solve it: Using the RIOT/ICE-L matrix to help guide intensification decisions! [Webinar]. National Center on Intensive Intervention at the American Institutes for Research. Available online: https://intensiveintervention.org/resource/using-matrix-guide-intensification (accessed on 14 December 2023).

- Horn, A. L., Gable, R. A., & Bobzien, J. L. (2020). Constant time delay to teach students with intellectual disability. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 64(1), 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C. A., & Lee, J.-Y. (2019). Effective approaches for scheduling and formatting practice: Distributed, cumulative, and interleaved practice. Teaching Exceptional Children, 51(6), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C. A., Morris, J. R., Therrien, W. J., & Benson, S. K. (2017). Explicit instruction: Historical and contemporary contexts. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 32(3), 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. (2004). Public law No: 108-446. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/108thcongress/house-bill/1350 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Kaldenberg, E. R., Watt, S. J., & Therrien, W. J. (2015). Reading instruction in science for students with learning disabilities: A meta-analysis. Learning Disability Quarterly, 38(3), 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S. (Host). (2024, February 28). Cognitive load theory: Four items at a time, with Greg Ashman [Audio podcast]. Available online: https://amplify.com/episode/science-of-reading-the-podcast/season-8/episode-11-cognitive-load-theory-four-items-at-a-time-with-greg-ashman/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Ledford, J. R., Lane, J. D., Elam, K. L., & Wolery, M. (2012). Using response-prompting procedures during small-group instruction: Outcomes and procedural variations. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(5), 413–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemons, C. J., Allor, J. H., Al Otaiba, S., & LeJeune, L. M. (2016). 10 Research-based tips for enhancing literacy instruction for students with intellectual disability. Teaching Exceptional Children, 50(4), 220–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, A. R., Van Stratton, J. E., & Sherlund-Pelfrey, P. (2024). A systematic review of explicit instruction and frequency building interventions to teach students to write. Education and Treatment of Children, 47(2), 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morano, S. (2019). Retrieval practice for retention and transfer. Teaching Exceptional Children, 51(6), 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, T. E. (2004). Simultaneous prompting: A review of the literature. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 39(2), 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Morse, T. E. (2023). A preliminary examination of the use of simultaneous prompting to teach math content to students with disabilities. International Journal of Education, Learning and Development, 11(1), 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, T. E., & Nguyen, G. (2024,An investigation of simultaneous prompting to teach an addition algorithm to preschool students. Journal of Education and Learning, 13(1), 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, T. E., & Nguyen, G.-N. T. (2025). Improving K-12 schooling in response to the COVID-19 pandemic through tutoring: One step forward in addressing an ongoing public health concern. COVID, 5(4), 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J. (2023). What to do when students don’t respond to interventions. Center on Multi-Tiered System of Supports. Available online: https://mtss4success.org/blog/students-dont-respond-interventions (accessed on 30 September 2023).

- Richards, S. B. (2019). Single subject research: Applications in educational settings (3rd ed.). Cengage. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. S., O’Shea, L. J., & O’Shea, D. J. (2020). Student teacher to master teacher: A practical guide for educating students with special needs (4th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Spooner, F., Pennington, R., Anderson, A., & Williams, T. R. (2025). The application of time delay to teach students with extensive support needs. Teaching Exceptional Children, 57(5), 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, E. A., Leroux, A., Mowbray, H. H., & Lee, G. S. (2023). Evaluating the effects of adding explicit instruction to a word-problem schema intervention. Exceptional Children, 89(3), 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, E. A., & Mowbray, H. H. (2024). Using a vocabulary map routine to explicitly teach mathematics vocabulary. Teaching Exceptional Children, 57(2), 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapp, M. C., Pennington, R. C., Clausen, A. M., & Carpenter, M. E. (2021). Systematic review of mand training parameters for students with intellectual and developmental disabilities in school settings. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 56(4), 437–453. [Google Scholar]

- Tekin-Iftar, E., Olcay-Gul, S., & Collins, B. C. (2019). Descriptive analysis and meta analysis of studies investigating the effectiveness of simultaneous prompting procedure. Exceptional Children, 85(3), 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The IRIS Center. (2009). Evidence-based practices (Part 1): Identifying and selecting a practice or program. Available online: https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/ebp_01/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Walker, G. (2008). Constant and progressive time delay procedures for teaching children with autism: A literature review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(2), 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walkey, J. (2024). The impact of explicit phonics instruction on emergent literacy. Canadian Journal for New Scholars in Education, 15(2), 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, R. E., Alberto, P. A., & Fredrick, L. D. (2011). Simultaneous prompting: An instructional strategy for skill acquisition. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 46(4), 528–543. [Google Scholar]

- Weingarten, Z., Bailey, T. R., & Peterson, A. (2019). Strategies for scheduling: How to find time to intensify and individualize intervention. National Center on Intensive Intervention, Office of Special Education Programs, U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://intensiveintervention.org/resource/strategies-scheduling-how-find-time-intensify-and-individualize-intervention (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Wolery, M., Ault, M. J., & Doyle, P. M. (1992). Teaching students with moderate to severe disabilities: Use of response prompting strategies. Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Yell, M. L., & Bateman, D. (2020). Defining educational benefit: An update on the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District (2017). Teaching Exceptional Children, 52(5), 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Grade | Disability | Race | Vocabulary Words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Darby | 11 | Autism | African American | rent, hired, wealthy, banker, salary, roommate |

| Jack | 12 | Intellectual disability | Caucasian | buy, cash, own, sell, poor, raise |

| David | 12 | Intellectual disability | African American | pay, earn, debt, save, poor, cent |

| Cody | 11 | Intellectual disability | African American | raise, cost, wealthy, earn, budget, sign |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morse, T.E. A Systematic Instructional Approach to Teaching Finance Vocabulary to Students with Moderate-to-Significant Disabilities. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091180

Morse TE. A Systematic Instructional Approach to Teaching Finance Vocabulary to Students with Moderate-to-Significant Disabilities. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091180

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorse, Timothy E. 2025. "A Systematic Instructional Approach to Teaching Finance Vocabulary to Students with Moderate-to-Significant Disabilities" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091180

APA StyleMorse, T. E. (2025). A Systematic Instructional Approach to Teaching Finance Vocabulary to Students with Moderate-to-Significant Disabilities. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1180. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091180