Abstract

Existing educational leadership research consistently emphasizes the importance of empowering and supporting classroom teachers to develop essential teaching experiences and leadership skills, enabling them to become autonomous curriculum developers and thinkers. This study aimed to explore the perceptions and understanding of distributed pedagogical leadership among Kenyan preservice professional actors in their respective contexts. It also examined the significance and impact of this practice on enhancing and strengthening the teaching and leadership abilities of teacher educators, thereby empowering them as effective pedagogical leaders in the classroom. The study employed a mixed methods design with a convergent parallel approach, using purposive sampling to select 83 participants, including administrative leaders, formal teacher leaders, and teacher educators from five public and private preservice teacher training colleges. Data collection involved semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions for qualitative insights, and an online survey for quantitative data. Results show that principals and formal teacher leaders play a key role in empowering teacher educators by distributing pedagogical leadership responsibilities among all professional actors. However, teacher educators felt that the distribution of tasks and responsibilities was uneven, which hindered effective implementation. This study also highlights how employer policies, through principals, influence the distribution of pedagogical leadership responsibilities.

1. Introduction

There is growing interest in equipping classroom teachers with the necessary teaching skills and leadership experiences to promote independent curriculum development and critical thinking. This trend has led to increased efforts to empower educators by enhancing effective teaching experiences and leadership skills and boosting student achievement in educational settings (Contreras, 2016). Recent empirical research studies on educational leadership emphasize the importance of school leaders, such as principals, head teachers, their deputies, and formal teacher leaders, in supporting pedagogical improvement by sharing leadership responsibilities with classroom teachers (Heikka et al., 2021; Arden & Okoko, 2021).

Additionally, implementing distributed pedagogical leadership (DPL) practice in learning ecosystems is advocated as a model where heads of learning organizations delegate administrative tasks and pedagogical leadership responsibilities to multiple professional actors, particularly classroom teachers (Heikka, 2014). This approach empowers teacher leaders and teachers with the confidence, authority, and ability to lead, guide, facilitate, and influence the effective implementation of curriculum and pedagogical practices in and out of the classroom (Heikka, 2014; Heikka et al., 2021; Lovett, 2023), resulting in improved students’ learning outcomes.

Moreover, DPL is regarded as a best practice that allows teacher leaders and teachers to create, innovate, and collaborate with students while sharing authority in decision-making processes that impact the quality of teaching and learning activities in the classroom (Bøe & Hognestad, 2017; Brecht, 2022; Chen, 2023). Teaching is viewed as an instructional process that embodies leadership, enabling teachers to assume leadership roles in pedagogical activities through regular interactions with colleagues, timely lesson preparation, and effective facilitation of student learning (Katzenmeyer & Moller, 2009; Zydziunaite & Jurgile, 2023). The reviewed literature suggests a distribution of pedagogical leadership responsibilities (allocation of resources, participation in collective decision-making processes, and the formulation of curriculum designs) from top to bottom, with teacher leaders taking on leadership roles while classroom teachers serve as both as leaders and facilitators of learning and curriculum implementation (Ali et al., 2021; Arden & Okoko, 2021; Fairman & Mackenzie, 2015; Sharar & Nawab, 2020).

Additionally, in the past decade, the practice of DPL in educational contexts, mainly in Europe and Asia, has gained popularity among educational leadership researchers at different scholarly levels. Most of these scholars have developed an interest in exploring the enactment of this concept in diverse learning communities as a practice that promotes and enhances quality teaching and leadership skills among working teachers and improves learning among students (Arden & Okoko, 2021; Bøe & Hognestad, 2017; Heikka et al., 2021; Yang & Lim, 2023). Furthermore, involving teachers in leading pedagogical activities is considered an alternative approach to changing school leadership practice and the improvement of teaching for pedagogical development (Sharar & Nawab, 2020).

Furthermore, in response to modern societal demands, the need for overall school improvements and pedagogical development to achieve sustainable learning outcomes is crucial. This involves restructuring, modernizing, and transforming leadership and learning frameworks within educational settings (Contreras, 2016; Namunga & Otunga, 2012). The adoption of the DPL concept as a leadership model plays a crucial role in achieving successful pedagogical outcomes, involving teachers’ participation in sourcing and providing pedagogical resources, as well as engaging in active, collaborative decision-making processes (Heikka & Suhonen, 2019). This approach aims to enhance students’ learning experiences across various educational organizations (Yang & Lim, 2023). However, in developing countries like Kenya, widespread recognition and implementation of the DPL concept as a vital educational leadership practice for pedagogical improvement and student success remain limited, especially in preparing future teachers as pedagogical leaders through empowered teacher educators. Additionally, there is a significant gap in the existing literature regarding this concept, particularly within preservice teacher education contexts.

Rationale of This Study

Foundationally, preservice teacher education programs in Kenya are designed to equip future teachers with the knowledge and skills needed for learning and applying 21st-century competencies in practice (Katitia, 2015; Namunga & Otunga, 2012). As postulated by Katitia (2015), teachers are not only curriculum thinkers but also developers and implementers; therefore, future teacher preparation is crucial in producing qualified teachers to lead pedagogical development in the classroom. To prepare competent future teachers as pedagogical leaders, it is necessary to ensure that teacher educators have the required knowledge and skills to actively participate in the decision-making process and have a collaborative attitude towards professional practice in schools that harness their teaching experiences and leadership skills (Afalla & Fabelico, 2020).

In addition, principals or heads of institutions, as center directors, and formal teacher leaders are required to establish a community of practice that fosters effective communication, quality learning for student teachers, and desired pedagogical development (Heikka, 2014; Okoth, 2016; Otieno, 2016). However, in Kenya, historical professional career stagnation and limited opportunities for advancement among teacher educators have increased leadership reluctance. This is a result of strict, centralized discriminatory policies, favoritism, and selective career progression regulations by the Teachers Service Commission, the employer of teachers, which have obstructed teachers’ aspirations to assume leadership positions (Katitia, 2015; Ngaruiya, 2023; Otieno, 2016).

Therefore, this study aimed to explore the understanding and perceptions of professional actors regarding the enactment of distributed pedagogical leadership practices in preservice teacher education contexts in Kenya. Additionally, the study explored how this practice aids teacher educators in developing effective teaching skills and empowers them to become strong pedagogical leaders in the classroom. The study involved professional actors as participants, including administrative leaders, such as principals, deputy principals, deans, and academic registrars; formal teacher leaders, such as heads of departments and subjects; and teacher educators responsible for training future classroom teachers.

Therefore, to achieve the intended research aims and objectives and address the identified gaps, this study was directed by the following research questions:

- How do professional actors in preservice teacher education contexts understand and perceive the implementation of distributed pedagogical leadership practices?

- What responsibilities do administrative leaders, teacher leaders, and teacher educators have during the implementation of DPL practices?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Significance of Distributed Pedagogical Leadership in Practice

Bøe and Hognestad (2017, 2024) define Distributed Pedagogical Leadership (DPL) as a hybrid leadership concept that helps explain how teachers take on leadership roles and become key figures in leading their teams. They explain that when formal or informal pedagogical leadership responsibilities are shared among staff members, teacher leaders, and their colleagues, they tend to work together interdependently in their teams (Abel, 2016). To foster a strong culture of teacher-led leadership in learning organizations, it is important to promote teamwork and professional collaboration as best practice principles in implementing DPL (Bøe et al., 2022; Bøe & Hognestad, 2017, 2024).

Furthermore, Jäppinen and Sarja (2012) opined that DPL practices involve the sharing organizational goals, visions, aims, values, and interests to achieve more than what multiple actors could achieve separately. DPL practices actively involve every staff member in the learning community (Jäppinen, 2012). Everyone actively participates in a collaborative and dynamic process of pedagogical improvement through shared knowledge and skills that create synergy in diversity (Jäppinen, 2012; Jäppinen & Sarja, 2012). Collaborative leadership in DPL is the essence of interdependence that is enriched with shared understanding and the creation of synergy within a professional learning community (Heikka, 2014; Jäppinen, 2012).

As a delegated responsibility within learning spaces, DPL is when pedagogical leadership responsibilities are distributed to multiple professional actors, with teacher leaders and teachers acting as pedagogical leaders, performing similar tasks independently but in an interdependent manner (Bøe et al., 2022; Bøe & Hognestad, 2017; Heikka et al., 2021). Engaging teachers in leadership responsibilities ensures that everyone is involved in collective enactment processes, thus supporting and guiding students’ learning paths for quality pedagogical achievements (Grice, 2019; Lovett, 2023; Yang & Lim, 2023). The collaborative work of principals and teachers in a learning ecosystem is carried out through mentoring their colleagues, peer observation and learning, peer coaching, and mutual reflective practice, which significantly increases the potential of effective teacher leadership and future excellent administrators (Bøe & Hognestad, 2024; Katzenmeyer & Moller, 2009).

Moreover, Dickerson et al. (2021) succinctly asserted that by distributing leadership responsibilities to teacher educators, they become the greatest pillars of teacher education programs as they collectively collaborate in curriculum development and implementation in their respective teams. They inspire reflective practices and offer a wide range of professional learning skills with their peers and collaborative actions with other stakeholders (Heikka, 2014; Veletić et al., 2023; Yang & Lim, 2023). Sharing and independently but interdependently enacting leadership responsibilities is geared toward improving teaching and learning, thus identifying both teacher educators as pedagogical leaders in leading the learning processes (Heikka et al., 2021; Meyer & Bendikson, 2021).

2.2. Conceptual Framework

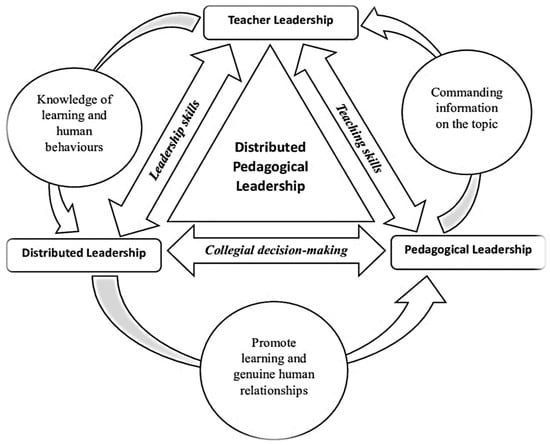

This study intended to contextualize the concept of DPL by providing a brief review of the relevant literature and empirical studies from various global contexts. Additionally, it developed a conceptual framework based on the concepts of distributed leadership, pedagogical leadership, and teacher leadership to guide the data collection and analysis processes. The conceptual framework is anchored in the dimensions of DPL and is informed by the interrelated principles of distributed leadership, pedagogical leadership, and teacher leadership within a learning ecosystem.

Administrative leaders and teacher leaders are responsible for the distribution of tasks and responsibilities in any learning ecosystem (Heikka, 2014; Veletić et al., 2023). Through the implementation of distributed leadership, all professional actors are afforded opportunities to cultivate their leadership skills and enhance their teaching and learning practices (Yang & Lim, 2023). Distributed leadership emphasizes the value of sharing leadership responsibilities in activities such as curriculum implementation, collaborative learning, and pedagogical development within the community of practice (García Torres, 2019; Heikka, 2014; Kılınç, 2014). Through the administrative leaders, they are encouraged to engage actively in the collegial decision-making process, as depicted in the conceptual model presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the study.

To effectively participate in the implementation of pedagogical leadership, teacher educators, acting as pedagogical leaders, must possess several critical leadership competencies (Bøe & Hognestad, 2024). According to Sergiovanni (1998), pedagogical leadership involves building and investing in human capital to strengthen students’ academic capital and teachers’ professional capital. This is achieved by adding value to the teaching and learning processes and supporting the development of sustainable and quality pedagogical development (Fonsén & Soukainen, 2020; Hognestad & Bøe, 2025; Sergiovanni, 1998). Human capital investment includes a solid theoretical understanding of learning and human behavior, the ability to create positive learning environments and build meaningful relationships, a strong command of the subject matter, and effective teaching management skills that facilitate improved student learning (Afalla & Fabelico, 2020, p. 224).

In the context of preservice teacher education, both teacher leaders and teacher educators are viewed as active curriculum thinkers and implementers, involved in the enactment of leadership responsibilities (Bøe et al., 2022; Contreras, 2016; Heikka et al., 2021). To support the development of teacher leadership abilities, learning organizations should effectively distribute pedagogical leadership responsibilities to nurture and enhance their teaching skills (York-Barr & Duke, 2004). The practice of distributed leadership begins with fostering self-leadership skills that contribute to personal and professional growth (Lovett, 2023). A key component of distributed pedagogical leadership is empowering teachers to master content knowledge in the classroom and actively engage in collegial decision-making processes that influence the quality of teaching and learning processes (Heikka, 2014). Moreover, to refine leadership skills, all professional actors must engage in both formal and informal teacher leadership responsibilities and possess the necessary experience and understanding of learning and human behavior essential for effectively realizing the organization’s visions and strategies (Afalla & Fabelico, 2020; Bøe et al., 2022; Heikka et al., 2021; Heikka & Suhonen, 2019; York-Barr & Duke, 2004). Through the sharing of tasks within the framework of distributed leadership, principals and teacher leaders empower teachers to promote inclusive learning, foster authentic human relationships, and support teaching and learning as pedagogical leaders, both inside and outside the classroom (Veletić et al., 2023).

However, it is important to note that in preservice teacher education contexts, the responsibility for distributing pedagogical leadership tasks primarily falls on the principals, who serve as the chief pedagogical leaders within learning organizations. Conversely, classroom teachers can exercise their distributed leadership responsibilities to positively impact student achievement by cultivating trusting relationships with principals, formal teacher leaders, and colleagues within their learning communities (Yang & Lim, 2023).

The literature review and empirical studies highlight a significant gap in research: there are currently no known global studies examining how professional actors, especially administrative leaders and teacher leaders, implement the concept of DPL to nurture leadership skills and enhance the quality of pedagogical work among teacher educators in preservice teacher education contexts. To address this gap, this study aims to explore how DPL fosters collective and collaborative engagement among professional actors in preparing future teachers to facilitate and enhance quality pedagogical development. Consequently, this research will investigate the significance of DPL practices and their impact on developing quality teaching experiences and effective leadership skills among these actors, which are essential for preparing future educators. The motivation for this investigation arises from ongoing reforms in teacher education through a competency-based education system in Kenya (Ngaruiya, 2023). These reforms seek to improve the quality of pedagogical work for administrative leaders, teacher leaders, and teacher educators, ultimately facilitating desired learning outcomes for student teachers within the framework of summative assessment and evaluation in national teacher education (KICD, 2016, 2017, 2019).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

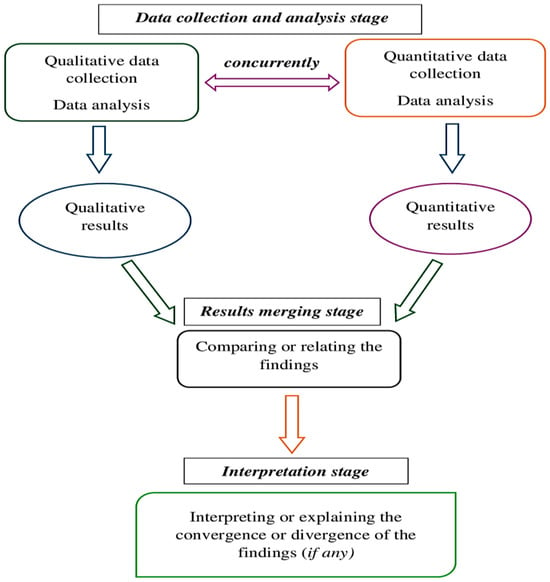

A mixed methods research (MMR) approach was employed, specifically utilizing a convergent parallel design to concurrently collect, analyze, and integrate both qualitative and quantitative data (Nguyen et al., 2020). According to Tashakkori and Teddlie (2016), MMR designs facilitate the combination of numerical and narrative methodologies to generate new knowledge, ideas, or concepts. This synthesis fosters an empirical synergy that neither method can achieve independently. As depicted in Figure 2, this approach enables researchers to attain a more comprehensive understanding of the central phenomenon by examining whether the results converge or diverge (Demir & Pismek, 2018). To ensure a thorough comprehension of the data and to achieve corroboration and triangulation (Johnson & Christensen, 2012), a variant parallel database was utilized. In this method, both qualitative and quantitative strands were analyzed independently yet simultaneously, with comparisons being made solely during the discussion and interpretation phase (Demir & Pismek, 2018; Gunbayi, 2020; Sorm & Gunbayi, 2022).

Figure 2.

Steps for implementing the research (Source: Adapted and modified from Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research by Creswell and Plano Clark (2018, p. 70).

3.1.1. Research Procedure

These research procedures were symbolized as qualitative and quantitative data. A convergent parallel method entailed that the authors conducted parallel and simultaneous data collection processes, analysis, and interpretation using quantitative and qualitative elements in the same phase of the research procedures (Johnson & Christensen, 2012), weighing both strands equally, i.e., QUAL + QUAN (Schoonenboom & Johnson, 2017), analyzes the two components independently and concurrently, and then interprets the results together (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018; Sorm & Gunbayi, 2022).

3.1.2. Research Sites

This study was conducted at public and private preservice teachers’ training institutions in Kenya. Five institutions were sampled through purposeful random sampling, which offered insightful knowledge and experience into the phenomenon under study (Cohen et al., 2018; Creswell & Creswell, 2018). These institutions are in diverse geographical locations with unique, complex, and dynamic leadership cultures and practices.

3.2. Participants and Sampling Procedures

We reached out to relevant institutions through our official email addresses to connect with specific individuals and research sites. In our communication, we clearly outlined the purpose of our study and identified the targeted participants. Utilizing a mixed-methods research sampling approach, we specifically employed purposeful random sampling (Cohen et al., 2018). Following this, we sent requests for participation to the individuals we had identified. From a pool of over 150 teacher educators across five institutions, 83 participants volunteered, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data on the research participants.

Among the 12 administrative leaders (principals, deputy principals, academic registrars, and deans of students), only 8 volunteered to participate in semi-structured interviews. The administrators were to provide information on their perception and implementation of DPL practices within their respective centers. We selected these individuals based on their experiences as teacher educators, anticipating that their professional backgrounds in preservice teacher education would provide valuable insights (Creswell, 2014; Levitt et al., 2018). Similarly, 75 participants (teacher leaders and educators) were engaged in both focus group discussions and completed online survey questionnaires. They were included in the study to examine their perception, understanding, and involvement in the implementation of DPL practices within their respective contexts.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

Before the study, we carefully considered key ethical aspects. We obtained approval from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Szeged (Reference number: 8/2022) and secured permission from Kenya’s Ministry of Education, through the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (License No: NACOSTI/P/22/19154), as well as from the principals of the participating institutions, to access the participants. Individuals were informed of their voluntary participation in the study and were made aware of their right to withdraw at any time. Furthermore, we guaranteed the confidentiality and anonymity of the participants and the data collected (Yin, 2018). All participants who agreed to take part in the study signed consent forms (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The data gathered was securely stored to protect participants from any intimidation or bias.

3.4. Instrumentation

3.4.1. Interviews and Focus Group Discussion Protocols

Two interview protocols were used for semi-structured and focus group discussions (FGDs) to ask additional probe questions and understand the reasons behind participants’ responses (Demir & Pismek, 2018). The protocols contained open-ended questions to gather nuanced and more in-depth data and to eliminate any misunderstandings or biases that can occur during face-to-face interviews (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). The semi-structured interview protocol encompassed eight factors: demographics; stakeholder perceptions; leadership capacity; understanding of the concept; distribution of leadership responsibilities; decision-making processes; benefits; and challenges faced. Additionally, during the interviews, probe questions, not included in the interview protocol, were utilized to gain a deeper understanding of participants’ perceptions and attitudes regarding the concept of DPL (Demir & Pismek, 2018). The schedule for the focus group discussions comprised 10 statements: perception of leadership; distribution of pedagogical leadership; delegation of roles and responsibilities; nurturing leadership capacity; the influence of leadership on the quality of teaching and learning; involvement in decision-making processes; and the distribution of pedagogical leadership responsibilities among teacher educators.

3.4.2. Survey Questionnaire

An anonymous online survey questionnaire was adapted from a tool created by Aziz et al. (2022) and was further modified to suit the context of the current study. The questionnaire was created and hosted using Google Forms. The questionnaire consisted of three main parts. The first part included the informed consent and participation acceptance. The second part contained 35 closed-ended statements divided into six factors of DPL. The third part gathered demographic information from teachers, including gender, age, teaching experience, and leadership positions, through six questions.

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

3.5.1. Mixed Methods Data Analysis

The primary researcher was actively involved at the institutions throughout the data collection phase. During this time, five semi-structured interviews and three focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted. To address the research questions, a convergent mixed methods design was utilized for concurrent analysis of the raw datasets, as illustrated in Figure 3 (Cohen et al., 2018; Yin, 2018). Initially, the two datasets were analyzed independently, employing distinct analytical tools. The results were then compared for triangulation, which facilitated the identification of additional evidence or differing outcomes and allowed for complementary findings (Levitt et al., 2018; Varlık et al., 2022; Xie et al., 2021). The semi-structured interviews, FGDs, and surveys were designed to investigate the participants’ perceptions and understanding of the practice of DPL.

Figure 3.

Analytical procedure of the results (Source: Self-developed from Creswell and Creswell (2018) and Creswell and Plano Clark (2018).

3.5.2. Qualitative Data

We conducted a thorough process of collecting and analyzing qualitative data to address the perceptions and understanding of principals, teacher leaders, and teacher educators regarding the implementation of DPL practices within their contexts. All semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions were recorded using a digital audio recorder. Each semi-structured interview lasted approximately 30 min, while the focus group discussions ranged from 30 to 45 min. The recordings were subsequently uploaded and transcribed verbatim utilizing the audio feature in Microsoft Word. The transcriptions were then printed for evaluation, ensuring accuracy, and proofreading against the original audio recordings (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). To enhance the reliability of the qualitative data, electronic copies of the transcriptions were sent to each participant for member checking. This process allowed them to validate the accuracy of the transcriptions, the representation of their responses, and the reflection of their experiences (Creswell & Creswell, 2018).

The study adhered to the guidelines set forth by Creswell and Plano Clark (2018) for coding qualitative data. Data collected from semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions with principals, teacher leaders, and teacher trainers were coded iteratively. This coding process facilitated the identification of key themes. A hybrid approach to coding was employed, blending both deductive and inductive methods to analyze the data. The process began with pre-established codes, followed by a line-by-line analysis using initial coding techniques. This approach enabled the mapping of new codes that emerged organically from the data rather than being predetermined (Cohen et al., 2018; Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Inductive coding proved essential, as the participants had a limited understanding of the concept of DPL.

3.5.3. Quantitative Data

Quantitative data were collected from teacher educators to explore their responsibilities in implementing DPL practices. Computer-assisted quantitative data analysis software, the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 27) program, was used to examine and analyze collected data. The authors explored the data by inspecting the raw data and conducting descriptive analyses (mean, standard deviation, and variance of responses) of each of the items in the scales to ascertain the emerging general trends in the data (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018).

For quantitative reliability and validity tests, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to validate the model’s fit to the measurement models in the teacher educators’ scale. The scale reliability test was performed through CFA due to the sample size of below 100 (Creswell, 2019; Yin, 2018). Similarly, one-way ANOVA and independent samples t-test were used to examine the perceptions of teacher educators on the pedagogical leadership responsibilities of the principals in the enactment of DPL practices in their contexts (Yin, 2018).

To measure the research variables, various statistical tests were employed, including the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index (KMO), Chi-squared test, Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), goodness-of-fit index, comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) (Creswell, 2019; Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2009). Descriptive and inferential analyses were conducted to facilitate the comparison of the quantitative dataset with the qualitative data. To verify the validity and reliability of the qualitative data, the researchers reviewed and verified the collected data using multiple sources. They acted as a single coder to ensure consistency throughout the study (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Yin, 2018). Subsequently, the analyzed quantitative data were integrated with the qualitative data during the interpretation stage (Demir & Pismek, 2018; Kelly, 2021; Razali et al., 2019). To enhance internal validity, data triangulation was employed, utilizing multiple data sources and combining both quantitative surveys and qualitative data collection methods. For corroboration and validation, the merged data were triangulated by directly comparing the qualitative findings with the quantitative statistical results, as illustrated in Figure 3.

4. Results

The study results are categorized based on the research questions, with each question being identified in the empirical qualitative and quantitative data findings.

4.1. Qualitative Findings

The qualitative findings were designed to address RQ1:

How do professional actors in preservice teacher education contexts understand and perceive the implementation of distributed pedagogical leadership practices?

4.1.1. Professional Actors’ Understanding and Perceptions on the Enactment of DPL Practices

The respondents’ thinking and understanding of the practice of DPL in preservice teacher education settings was that there was a need to involve all stakeholders in collective thinking, professional learning, and shared leadership responsibilities. The administrators, teacher leaders, and teacher educators perceived that synergy relationships started with the principal, as expressed by a teacher leader.

[…] It starts with the principal. He also teaches so that he can set an example. When he teaches, he can also know how the students are. All of us, from the principal downwards to the teacher educators, are all leaders. We are all offering some pedagogical leadership in one way or another. Either you are a subject tutor, a subject head, or a head of department.(Dean of Curriculum 1, interview)

4.1.2. Provision of Pedagogical Resources

Teacher educators reiterated that they were involved in the process of deciding the specific responsibilities to take in their classroom with support from the principal and other formal teacher leaders. However, the provision of adequate teaching and learning resources and timely, continuous professional learning development inhibited pedagogical development, as expressed by teacher educators.

[…] we failed because of a lack of, in fact, I could say, a lack of cooperation from the administration at that time. We would always be told that there are no resources. So, we have tried to put across some proposals that we need to do this, even though sometimes going to seminars has not always been easy. They are like going for seminars outside the college, professionally organized seminars, it is not always easy, but when the chance arises, one of us is released.(Teacher Educator, FDG)

4.1.3. Collective Decision-Making Processes

The principal and teacher educators were engaged in fostering curriculum reforms and development to improve the academic achievements of the student teachers. The teacher educators collectively participated and shared authority in decision-making processes, as expressed in the following excerpt:

I can say that our teachers are empowered. One is that they have very important content mastery. We don’t allow a teacher to go to class without knowing the information he/she is supposed to relay to the students. So, the teacher is first of all qualified, and also in that particular area, teachers undergo various training and seminars on the new Competency-Based Education.(Principal 2, interview)

The mode of principles that we have in our institution, and the kind of decisions I make, have to be consultative. I cannot just make any decision by myself. So, I have to sit down, consult, of course, the principal, and then the principal also consults the board of management. So, because the institution also has its own culture and has its own ways of executing its decisions or how they come up with routines that they have, we cannot go beyond the jurisdiction. So, it is consultative, and then a decision is made.(Deputy Principal 1, interview)

[…] The appointment comes with duties that they are supposed to do. Like you, ensure a smooth implementation of the curriculum […] We also offer technical advice to the principal on the resources required and manage the teachers. At that level, although the buck stops with the principal, there is so much that I may not do. What I am not able to handle here, I always forward it to my senior, the deputy principal, and it is then cascaded upwards.(Dean of Curriculum 2, interview)

The principal, as the chief pedagogical leader, ensured smooth enactment of all delegated leadership responsibilities and informed pedagogical practices.

Delegation is the key to reducing work stress. Greater stress because you find that, I think, in most cases, the head of an institution is in charge of virtually everything, and you can decide to do everything as one man for all activities, but then you have to delegate. So, my style is delegation. I delegate with clear instructions.(Principal 1, interview)

4.1.4. Implementation Challenges

The study also found that participants encountered challenges that hindered the fulfillment of their responsibilities. Teacher educators believed that the teacher trainees received more empowerment and support from principals and teacher leaders than what is indicated in the following excerpt:

My view is different because you will find most of the time the class secretaries and the leadership in the classroom are more empowered than the class tutor. … You find that they have that important information. They will be telling you that, for example: ‘We are going home for half term tomorrow.’ Or you see them coming with documents to be signed for… or you know, they seem like they are the ones who get information before the class tutor.(Teacher Educator, FGD)

The findings reveal that while leadership responsibilities were shared at various levels, the execution, perception, and interpretation of the practice by stakeholders varied among institutions due to differences in leadership styles and professional relationships within the learning communities. Furthermore, pedagogical leadership responsibilities were delegated to all, guided by the teachers’ employer policy and guidelines, as explained by a deputy principal.

So, as far as teaching and learning are concerned, already the Ministry of Education has laid out the protocol from the top, where we have the chief principal, we have the subject tutors, and, in the classroom, the class representatives. In delegated duties again, we have tried to come up with the same collaboration. So, we have what we call the head sections, and it is through the heads’ sections that we coordinate those areas, for example, the supervision of the business school, the supervision of hiring facilities, so that we now use the leaders in those departments to coordinate all the activities.(Deputy Principal 3, interview)

The participants confirmed the distribution of pedagogical leadership responsibilities through collaborative decision-making processes and shared delegated leadership duties. However, it was noted that principals and teacher educators’ employer, the Teachers Service Commission (TSC), still has greater influence in determining appointments to formal leadership positions in preservice teacher education contexts. The teacher employer significantly affects how pedagogical leadership responsibilities are shared among teacher educators. This limits the effectiveness of the practice and disrupts the consultations, collaborations, and collective decision-making processes of the stakeholders.

4.2. Quantitative Findings

The quantitative findings were intended to address RQ 2:

What responsibilities do administrative leaders, teacher leaders, and teacher educators have during the implementation of DPL practices?

4.2.1. Responsibilities of Professional Actors in the Implementation of DPL Practices

The descriptive statistics, including the mean and standard deviation for various factors, are presented in Table 2. The evaluation of leadership culture, strategies, and organizational structure within the organization yielded a high score (M (SD) = 3.73 (0.85), indicating that teacher educators were actively involved in the development of leadership cultures, strategies, and structures. These findings suggest that teacher educators have a strong understanding and perception of their responsibilities in implementing distributed pedagogical leadership within contexts. The highest mean values were recorded for statements indicating that the teacher educators agree that the distribution of responsibilities was formally agreed upon by senior administrators (M = 3.91, SD = 1.21) and teacher educators during consultative departmental meetings (M = 3.91, SD = 1.13). In contrast, the lowest mean value pertained to teacher educators taking on leadership responsibilities without established processes for accountability (M = 2.52, SD = 1.26).

Table 2.

The mean and standard deviations of the survey factors.

4.2.2. Teacher Educators by Gender

An independent sample t-test was conducted to determine whether significant differences existed between male and female teacher educators, as detailed in Table 3. The results indicate that there were no significant differences across all dimensions of the scale. Male and female teacher educators exhibited equal performance in all areas (p > 0.05). For example, male teacher educators had a mean score of M = 3.68 (SD = 0.86), while female teacher trainers achieved a mean score of M = 3.75 (SD = 0.87), demonstrating parity in their engagement with the development and design of leadership culture strategies and structures (t = −0.36, p = 0.72).

Table 3.

Teacher educators’ responsibilities by gender.

4.2.3. Teacher Educators’ Participation in Leadership by Age

An evaluation was conducted to assess the differences among research factors based on the age of teacher educators. One-way ANOVA was performed, and the results are presented in Table 4. The analysis revealed that there were no significant differences in teacher educators’ participation regarding the development of pedagogical leadership strategies and structures, the design and definition of organizational visions and strategies, involvement in shaping values and beliefs, collaboration in designing leadership functions, sharing authority in decision-making processes, distributing responsibilities, or participating in instructional creativity and innovation as related to their ages (p > 0.05).

Table 4.

Teacher educators’ participation in leadership responsibilities by age.

Teacher educators aged 30–39, 40–49, and 50–59 demonstrated similar trends in various areas, including the development of organizational strategies and structures (F = 1.95, p = 0.15), the co-creation and planning of visions and strategies (F = 0.81, p = 0.45), the definition of values and beliefs (F = 0.86, p > 0.43), collaboration and cooperation in leadership function development (F = 1.18, p = 0.31), shared authority in decision-making processes and distributed responsibilities (F = 0.66, p = 0.52), and participation in instructional creativity and innovation (F = 1.02, p = 0.37).

5. Discussion

This study aimed to explore how professional actors in preservice teacher education programs perceive, understand, and implement DPL practices. It further explored the roles and responsibilities of principals and formal teacher leaders in leveraging teaching and leadership skills through the effective application of DPL practices. The distinctiveness of this study lies in the involvement of multiple professional actors, particularly heads of institutions (principals and their deputies), teacher leaders, and teacher educators, in sharing pedagogical leadership responsibilities, as highlighted by Heikka et al. (2021). The research examines the unique yet interdependent execution of effective distributed pedagogical leadership responsibilities within preservice teacher education contexts, as well as the efficient distribution of these functions to enhance collaboration between principals and teacher educators (Heikka, 2014; Heikka et al., 2021; Yang & Lim, 2023).

The study was based on evidence from prior empirical research that indicated a correlation between the dimensions of DPL practices and the empowerment of teachers as pedagogical and teacher leaders (Bøe & Hognestad, 2017, 2024; Heikka, 2014; Heikka et al., 2021; Yang & Lim, 2023). These findings suggest that DPL practices enhance the quality of teaching for teacher educators and improve student learning outcomes (Gningue et al., 2022; Grant et al., 2010; Heikka et al., 2018; Yang & Lim, 2023). Furthermore, the study incorporated empirical research findings from various educational contexts (Bøe & Hognestad, 2024; Heikka & Suhonen, 2019; Yang & Lim, 2023) to underscore the necessity for further investigation into the significance of enacting DPL and implementing reforms within education systems. It also examined the roles of principals, deputy principals, and teacher leaders as administrative and pedagogical leaders in nurturing and empowering teacher educators as facilitators of learning, ultimately contributing to the effective distribution of pedagogical activities in the classroom and enhancing academic achievement (Bøe & Hognestad, 2017, 2024; Fernández Espinosa & López González, 2023).

The findings supported by the literature reviewed indicate that cultivating a culture of shared pedagogical leadership responsibilities aims to provide classroom teacher educators with opportunities to lead both within their classrooms and beyond (Shurr et al., 2022; Smylie & Eckert, 2018; Wieczorek & Lear, 2018; Zydziunaite & Jurgile, 2023). The findings from this study show that teacher educators are viewed not only as developers and implementers of curriculum but also as knowledge producers who assume the role of pedagogical leaders within the learning community (Chen, 2023). Consequently, promoting egalitarian collaborative engagement between principals and teacher educators is crucial for enhancing leadership and teaching skills aimed at quality pedagogical improvement. It was also noted that active collective decision-making processes emerge through synergistic collaborations and effective communication within departments (Bøe & Hognestad, 2024; Chen, 2023; Nguyen et al., 2020).

Teacher educators viewed the implementation of DPL practice as fostering interdependence. In this model, principals, in their role as lead pedagogical leaders, share equal responsibilities with teacher educators but interdependently execute delegated pedagogical leadership tasks (Heikka, 2014). Related studies indicate that the principal’s primary role as a center manager is to facilitate informed and interactive pedagogical practices (Bøe & Hognestad, 2024; Heikka et al., 2013, 2020). During focus group discussions and survey responses, teacher educators expressed their appreciation for the collaborative interdependence within their departments.

Many respondents expressed concern that certain responsibilities were distributed unevenly among the professional actors. While decision-making processes were predominantly coordinated by administrators and formal teacher leaders, most tasks were typically carried out in consultation with the principal or deputy principal. Furthermore, both administrators and teacher educators identified several challenges that hindered the effective implementation of leadership practices (Bøe & Hognestad, 2017, 2024). Internally, they highlighted issues such as heavy workloads, inadequate training and professional development, understaffing, and low enrollment of student teachers (Yang & Lim, 2023). Externally, they raised concerns regarding the stringent protocols and guidelines set forth by government agencies, including the Ministry of Education and the Teachers Service Commission, which significantly obstructed the effective enactment of DPL in their institutions.

The challenges identified are consistent with findings from related studies, such as those by Bøe and Hognestad (2017, 2024) and Yang and Lim (2023), which indicate that a shortage of teacher educators and understaffing significantly affect the quality of DPL practices. Notably, participants in the study expressed that principals and formal teacher leaders hold the dual responsibility of inspiring teacher educators to embrace teacher leadership roles and fostering distributed classroom tasks, participative structures, alongside a collaborative leadership culture. Such an environment is crucial for teacher educators to effectively undertake delegated pedagogical leadership responsibilities. Consequently, all teacher educators in preservice teacher education settings should be encouraged to take on both formal and informal leadership roles. Moreover, principals, as pedagogical leaders, should ensure that teacher educators are actively included in every decision-making process to effectively nurture and develop them into future teacher leaders.

5.1. Limitations

This study was conducted in only five of the more than 60 pre-service teacher training colleges in Kenya. Therefore, the findings may not be representative of similar institutions, which may vary in terms of geographical location, leadership styles, and cultural contexts. Nevertheless, the results offer valuable insights that could inform and guide future reviews of curricula, syllabi, and the restructuring of training programs within pre-service teacher education settings.

5.2. Implications

Practically, this study marks the first empirical research conducted in the field of pre-service teacher education in Kenya. As a result, its findings have the potential to inform similar research initiatives in pre-service teacher education across the globe. Additionally, from a theoretical perspective, the study builds upon existing knowledge to deepen understanding of the concept, validates the findings of previous studies, and contributes to ongoing discussions about the importance of enhancing collaborative, innovative DPL practices among educational leadership researchers, teacher education practitioners, professional actors, and policymakers, to extend these practices to various levels of educational contexts.

6. Conclusions and Directions for Further Research

The study established a connection between the concept of DPL and its practical application in empowering teacher educators to become both pedagogical and teacher leaders, inside and outside their classrooms. It recommends further investigations to explore how this practice contributes to enhancing collaborative learning, professional development, and the cultivation of competent future teacher leaders. Future research should also examine how educational professionals perceive the importance of distributing pedagogical responsibilities and teachers’ tasks within a learning ecosystem, particularly in achieving quality pedagogical outcomes for students.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.O.O. and K.J.; Methodology, P.O.O.; Formal analysis, P.O.O.; Investigation, P.O.O.; Writing—original draft, P.O.O., T.Z.O. and K.J.; Writing—review & editing, P.O.O., T.Z.O. and K.J.; Supervision, K.J.; Funding acquisition, K.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Scientific Foundations of Education Research Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and by the Digital Society Competence Centre of the Humanities and Social Sciences Cluster of the Centre of Excellence for Interdisciplinary Research, Development and Innovation of the University of Szeged. The authors are members of the New Tools and Techniques for Assessing Students Research Group.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the University of Szeged (protocol code 8/2022 and date of 5 July 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Similarly, written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to appreciate the support received from the Stipendium Hungaricum Tempus Public Foundation, Hungary, the Doctoral School of Education at the Institute of Education, University of Szeged. We also wish to thank our colleague, Achmad Hidayatullah for the technical statistical data analysis advice and round-the-clock assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abel, M. (2016). Why pedagogical leadership? McCormick Center for Early Childhood Leadership. McCormickCenter.nl.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Afalla, B. T., & Fabelico, F. L. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ pedagogical competence and teaching efficiency. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(11), 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W. R. H., Salleh, M. J., & Bin Ibrahim, M. B. (2021). Influence of teacher leadership and professional competency on the academic achievement of college students in English language in the Sultanate of Oman. Journal of World Englishes and Educational Practices, 3(9), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arden, C., & Okoko, J. M. (2021). Exploring cross-cultural perspectives of teacher leadership among the members of an international research team: A phenomenographic study. Research in Educational Administration and Leadership, 6(1), 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, A., Parveen, Z., & Shehzadi, K. (2022). Prevalence of distributed leadership in secondary schools of Punjab: Perspectives of teachers. Pakistan Social Sciences Review, 6(2), 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøe, M., Heikka, J., Kettukangas, T., & Hognestad, K. (2022). Pedagogical leadership in activities with children—A shadowing study of early childhood teachers in Norway and Finland. Teaching and Teacher Education, 117, 103787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøe, M., & Hognestad, K. (2017). Directing and facilitating distributed pedagogical leadership: Best practices in early childhood education. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 20(2), 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøe, M., & Hognestad, K. (2024). Enactments of distributed pedagogical leadership between early childhood centre directors and deputy directors in Norway. Southeast Asia Early Childhood Journal, 13(1), 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecht, D. R. (2022). Teacher leadership: A hybrid model proposal. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 7(3), 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-Y. (2023). What motivates teachers to lead? Examining the effects of perceived role expectations and role identities on teacher leadership behavior. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 53(1), 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras, T. S. (2016). Pedagogical leadership, teaching leadership and their role in school improvement: A theoretical approach. Propósitos Y Representaciones, 4(2), 231–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (2019). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (6th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, S. B., & Pismek, N. (2018). A convergent parallel mixed-methods study of controversial issues in social studies classes: A clash of ideologies. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 18(1), 119–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickerson, C., White, E., Levy, R., & Mackintosh, J. (2021). Teacher leaders as teacher educators: Recognising the ‘educator’ dimension of some teacher leaders’ practice. Journal of Education for Teaching, 47(3), 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairman, J. C., & Mackenzie, S. V. (2015). How teacher leaders influence others and understand their leadership. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 18(1), 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Espinosa, V., & López González, J. (2023). The effect of teacher leadership on students’ purposeful learning. Cogent Social Sciences, 9(1), 2197282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonsén, E., & Soukainen, U. (2020). Sustainable pedagogical leadership in Finnish early childhood education (ECE): An evaluation by ECE professionals. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(2), 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Torres, D. (2019). Distributed leadership, professional collaboration, and teachers’ job satisfaction in U.S. schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 79, 111–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gningue, S. M., Peach, R., Jarrah, A. M., & Wardat, Y. (2022). The relationship between teacher leadership and school climate: Findings from a teacher-leadership project. Education Sciences, 12(11), 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, C., Gardner, K., Kajee, F., Moodley, R., & Somaroo, S. (2010). Teacher leadership: A survey analysis of Kwa Zulu-Natal teachers’ perceptions. South African Journal of Education, 30, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grice, C. (2019). Distributed pedagogical leadership for the implementation of mandated curriculum change. Australian Council for Educational Leaders, 25(1), 56–71. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.757529150853046 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Gunbayi, I. (2020). Knowledge-constitutive interests and social paradigms in guiding mixed methods research (MMR). Journal of Mixed Methods Studies, 1(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikka, J. E. (2014). Distributed pedagogical leadership in early childhood education [Doctoral dissertation, Tampere of University]. [Google Scholar]

- Heikka, J. E., Halttunen, L., & Waniganayake, M. (2018). Perceptions of early childhood education professionals on teacher leadership in Finland. Early Child Development and Care, 188(2), 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikka, J. E., Hujala, E., Waniganayake, M., & Rodds, J. (2013). Enacting distributing pedagogical leadership in Finland: Perceptions of early childhood education stakeholders. In Researching leadership in early childhood education (pp. 255–273). Tampere University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heikka, J. E., Kahila, S. K., & Suhonen, K. K. (2020). A study of pedagogical leadership plans in early childhood education settings in Finland. South African Journal of Childhood Education, 10(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikka, J. E., Pitkäniemi, H., Kettukangas, T., & Hyttinen, T. (2021). Distributed pedagogical leadership and teacher leadership in early childhood education contexts. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 24(3), 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikka, J. E., & Suhonen, K. (2019). Distributed pedagogical leadership functions in early childhood education settings in Finland. Southeast Asia Early Childhood Journal, 8(2), 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hognestad, K., & Bøe, M. (2025). Teacher leaders as first-line leaders in early childhood education—Pedagogical leadership actions for best practice. Journal of Early Childhood Education Research, 14(1), 258–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäppinen, A.-K. (2012). Distributed pedagogical leadership in support of student transitions. Improving Schools, 15(1), 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäppinen, A.-K., & Sarja, A. (2012). Distributed pedagogical leadership and generative dialogue in educational nodes. British Educational Leadership, Management and Administration Society, 26(2), 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B., & Christensen, L. B. (2012). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches (4th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Katitia, D. M. O. (2015). Teacher education preparation program for the 21st century. Which way forward for Kenya? Journal of Education and Practice, 6(24), 57–63. Available online: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1078823 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Katzenmeyer, M., & Moller, G. (2009). Awakening the sleeping giant: Helping teachers develop as leaders (3rd ed.). Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, K. L. (2021). A convergent parallel mixed methods study measuring the impact of math-economics cross-curricular intervention [Doctoral dissertation, Columbus State University]. Available online: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/451 (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- KICD. (2016). Research report and draft framework for teacher education in Kenya. Research Report. Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development KICD. Available online: https://kicd.ac.ke/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/TeacherEducation.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- KICD. (2017). Basic education curriculum framework. Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development. Available online: https://kicd.ac.ke/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/CURRICULUMFRAMEWORK.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- KICD. (2019). Teacher education curriculum framework (pp. 1–69). Draft. Curriculum Framework. KICD. [Google Scholar]

- Kılınç, A. Ç. (2014). Examining the relationship between teacher leadership and school climate. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 14(5), 1729–1742. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, H. M., Bamberg, M., Creswell, J. W., Frost, D. M., Josselson, R., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2018). Journal article reporting standards for qualitative primary, qualitative meta-analytic, and mixed methods research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. American Psychologist, 73(1), 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovett, S. (2023). Teacher leadership and teachers’ learning: Actualizing the connection from day one. Professional Development in Education, 49, 1010–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F., & Bendikson, L. (2021). Pedagogical leadership. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namunga, N. W., & Otunga, R. N. (2012). Teacher education as a driver for sustainable development in Kenya. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2(5), 228–234. Available online: www.ijhssnet.com (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Ngaruiya, B. (2023). Competency based curriculum and its implications for teacher training in Kenya. Cradle of Knowledge: African Journal of Educational and Social Science Research, 11(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D., Harris, A., & Ng, D. (2020). A review of the empirical research on teacher leadership (2003–2017): Evidence, patterns, and implications. Journal of Educational Administration, 58(1), 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoth, T. A. (2016). Enhancing pedagogical leadership: Refocusing on school practices. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS), 12(2), 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otieno, M. A. (2016). Assessment of teacher education in Kenya. Available online: http://oasis.col.org/handle/11599/2648 (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Razali, F. M., Aziz, N. A. A., Rasli, R. M., Zulkefly, N. F., & Salim, S. A. (2019). Using convergent parallel design mixed method to assess the usage of multi-touch hand gestures towards fine motor skills among pre-school children. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(14), 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonenboom, J., & Johnson, R. B. (2017). How to construct a mixed methods research design. KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift Für Soziologie Und Sozialpsychologie, 69(Suppl. S2), 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergiovanni, T. J. (1998). Leadership as pedagogy, capital development, and school effectiveness. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharar, T., & Nawab, A. (2020). Teachers’ perceived teacher leadership practices: A case of private secondary schools in Lahore, Pakistan. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2(1), 100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shurr, J., Bouck, E. C., & McCollow, M. (2022). Examining teacher and teacher educator perspectives of teacher leadership in extensive support needs. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 45(2), 160–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smylie, M. A., & Eckert, J. (2018). Beyond superheroes and advocacy: The pathway of teacher leadership development. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(4), 556–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorm, S., & Gunbayi, I. (2022). The principals’ praxis of pedagogical leadership in nurturing teaching and learning in Cambodian primary schools. Journal of Mixed Methods Studies, 2, 47–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (Eds.). (2016). SAGE. Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (2nd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research: Integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Varlık, S., Sorm, S., & Günbayı, İ. (2022). Validity and reliability of the pedagogical leadership scale: Mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Studies, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veletić, J., Price, H. E., & Olsen, R. V. (2023). Teachers’ and principals’ perceptions of school climate: The role of principals’ leadership style in organizational quality. Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Accountability, 35, 525–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, D., & Lear, J. (2018). Building the “Bridge”: Teacher leadership for learning and distributed organizational capacity for instructional improvement. International Journal of Teacher Leadership, 9(2), 22–47. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, L., Han, S. J., Beyerlein, M., Lu, J., Vukin, L., & Boehm, R. (2021). Shared leadership and team creativity: A team-level mixed-methods study. Team Performance Management: An International Journal, 27(7–8), 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W., & Lim, S. (2023). Toward distributed pedagogical leadership for quality improvement: Evidence from a childcare centre in Singapore. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 51(2), 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- York-Barr, J., & Duke, K. (2004). What do we know about teacher leadership? Findings from two decades of scholarship. Review of Educational Research, 74(3), 255–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zydziunaite, V., & Jurgile, V. (2023). Lifeworld research of teacher leadership through educational interactions with students in a classroom: Three levels. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, Open Science Index 204, International Journal of Educational and Pedagogical Sciences, 17(12), 894–900. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).