Beyond Emotional Intelligence: Validation of a Model of Emotional Competence Applied to Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Approaches to Emotional Intelligence

1.2. Emotional Competencies

1.3. Emotional Competence and the Teaching Profession

1.4. The Vulnerability of the Teaching Profession

1.5. Assessment of Emotional Competencies

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

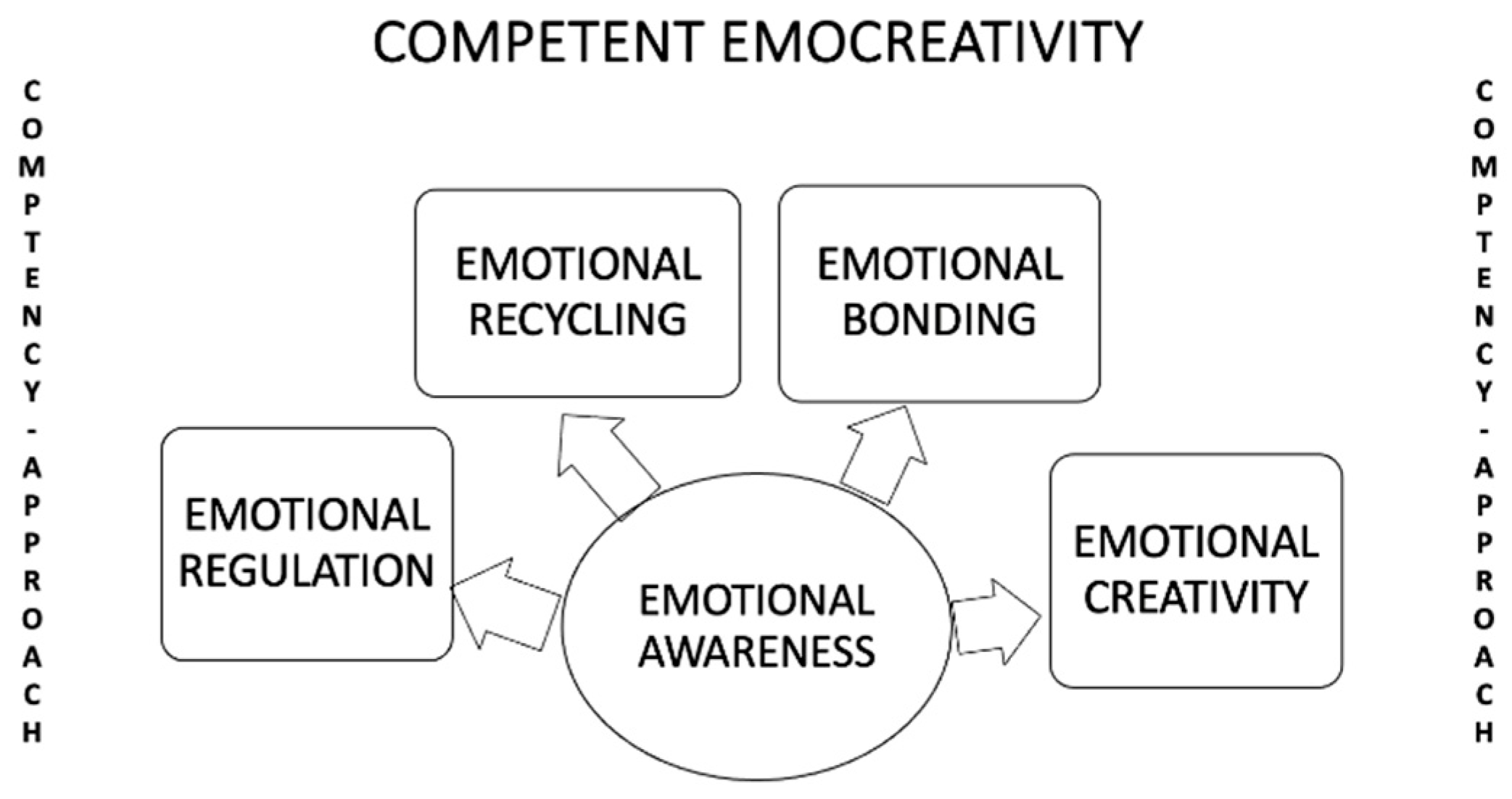

2.2. Instruments

- Emotional perception: Becoming aware of the bodily sensations associated with emotional experiences.

- Emotional recognition: Identifying one’s own emotions and those of others and accepting them without dissociating oneself from them.

- Emotional understanding: Understanding and analysing the emotions one experiences, their relationship to what has happened before, and their consequences.

- Emotional responsibility: Taking responsibility for one’s own behaviour, the consequences of one’s feelings, and the harm that can be done to oneself and others through behaviour derived from one’s emotions.

- Self-control: Regulating emotional impulsivity and its expression through reflexivity, tolerance for frustration, and overcoming difficulties.

- Emotional adjustment: Regulating the experience of one’s own emotions, and adjusting their intensity and duration, particularly those that manifest themselves in a maladjusted way and cause discomfort.

- Emotional recycling: Endogenously promoting adaptive emotions and states of emotional security, through which maladaptive emotions that are experienced can be displaced or replaced.

- Empathize: Identify, understand, and interpret other people’s emotions and experience emotions based on the feelings of others.

- Emotional communication: Expressing one’s own emotions, needs, and experiences to others without discomfort and demonstrating authenticity and closeness, as well as a willingness to listen actively and respectfully to the feelings shared by others.

- Emotional commitment: Connecting emotionally with others, showing appreciation, affection, and value toward them, and developing altruistic and supportive behaviours.

- Creative self-confidence: Self-assurance when expressing oneself as an original person who is different from others.

- Openness to change and innovation: Interest in unusual experiences and ideas and receptivity to what is different, new, or alternative, as well as a willingness to explore reality through the senses.

- Life entrepreneurship: Initiative to propose, develop, and implement entrepreneurial projects aimed at community well-being.

2.3. Procedure

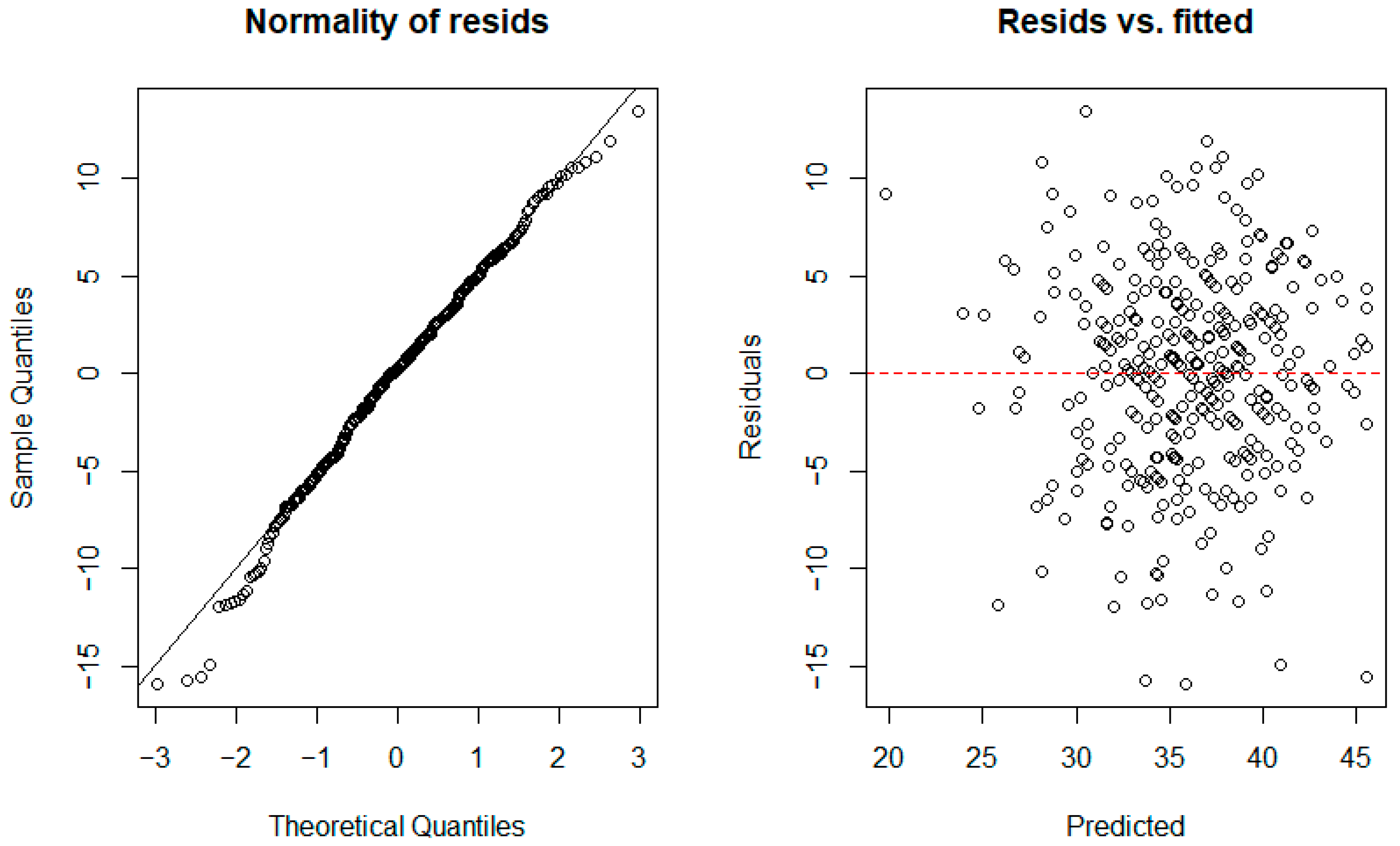

2.4. Data Analysis

- χ2/gL: Values ≤ 3 indicated a satisfactory fit.

- CFI (Comparative Fit Index) and TLI (Tucker–Lewis Index): ≥0.90 (acceptable) and ≥0.95 (excellent).

- RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation): ≤0.08 (adequate) and ≤0.05 (excellent).

- SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual): ≤0.08 as an acceptance threshold.

3. Results

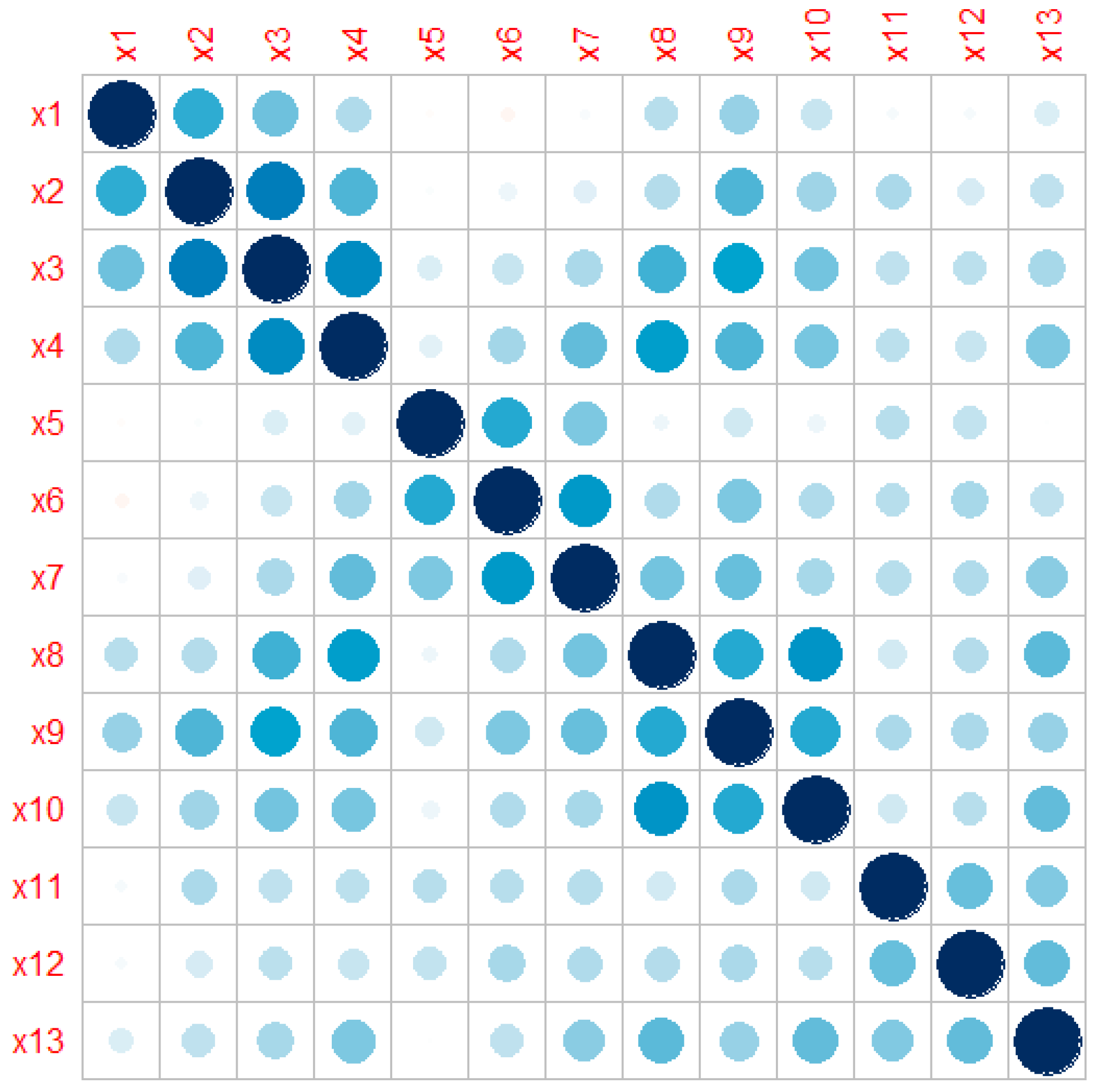

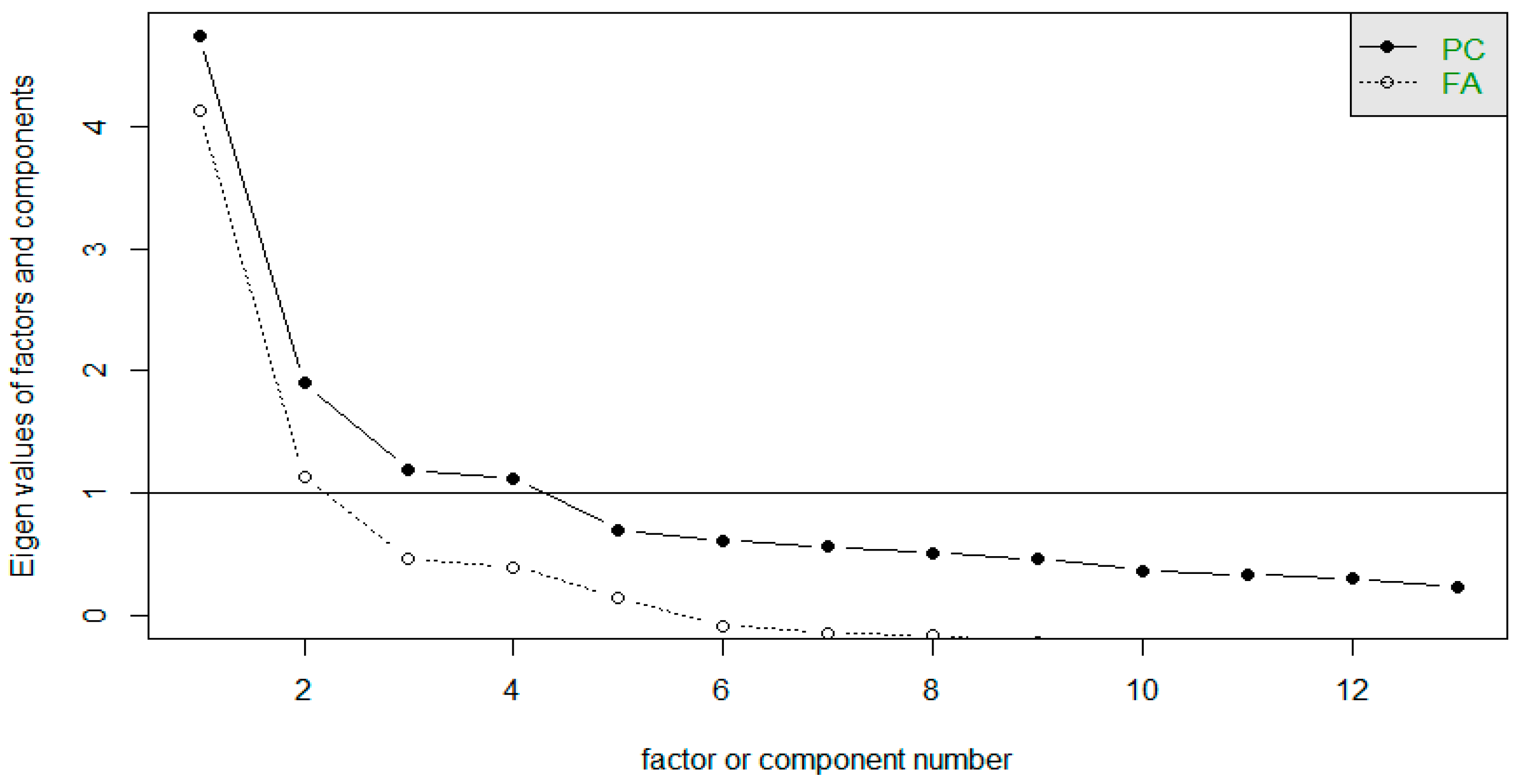

3.1. Factor Analysis of the Self-Assessment of Emotional Competences Questionnaire

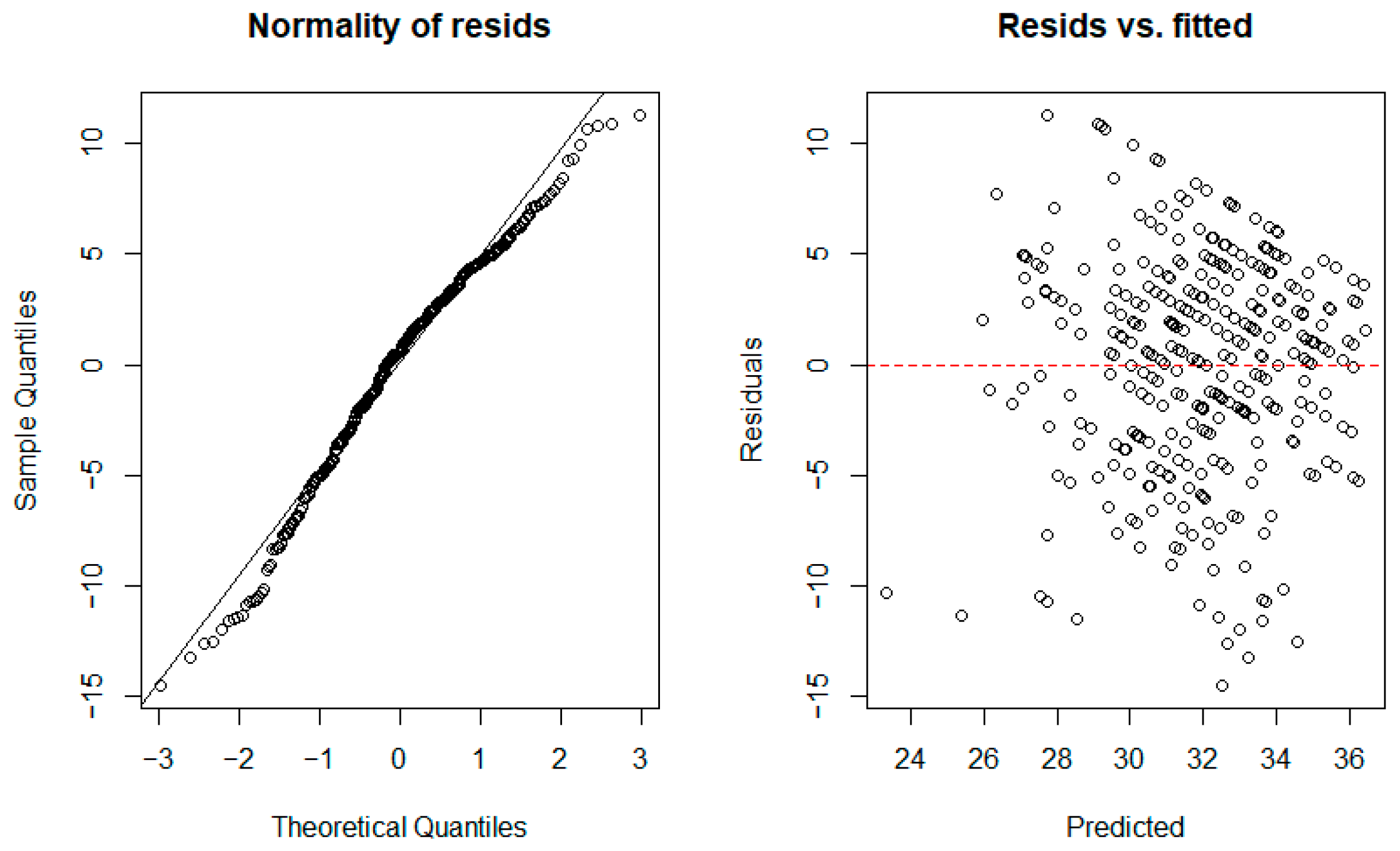

3.2. Relationship Between the Self-Assessment Questionnaire of Emotional Competencies (CACE) and the TMMS-24 Emotional Intelligence Test

3.3. Comparison of Emotional Competencies Between Practicing Teachers and Trainee Teachers

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Averill, J. R. (1999a). Creativity in the domain of emotion. In T. Dalgleish, & M. Power (Eds.), Handbook of cognition and emotion (pp. 765–782). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Averill, J. R. (1999b). Individual differences in emotional creativity: Structure and correlates. Journal of Personality, 67, 331–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-On, R., & Parker, J. D. (2000). The emotional quotient invetitorv: Youth version (EQ-i:YV). Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, E. S., Goetz, T., Morger, V., & Ranellucci, J. (2014). La importancia de las emociones y el comportamiento instructivo de los maestros para las emociones de sus estudiantes: Un análisis de muestreo de experiencias. Enseñanza y Formación del Profesorado, 43, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquerra Alzina, R. (2005). La educación emocional en la formación del profesorado. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 19(3), 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Brackett, M. A., & Salovey, P. (2007). La evaluación de la inteligencia emocional con el Mayer, Salovey, Caruso emotional intelligence test (MSCEIT). In J. M. Mestre, & P. Fernández-Berrocal (Coords.), Manual de inteligencia emocional (pp. 67–78). Pirámide. [Google Scholar]

- Busso, M., Cristia, J., Hincapié, D., Messina, J., & Ripani, L. (Eds.). (2017). Aprender mejor: Políticas públicas para el desarrollo de habilidades. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. [Google Scholar]

- Chinea, M. (2020). Salud mental y competencias emocionales en los docentes [Trabajo de Fin de Máster, Universidad Fernando Pessoa]. [Google Scholar]

- Collie, R. J. (2020). The development of social and emotional competence at school: An integrated model. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(1), 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J. (2025). Teachers’ perceived social-emotional competence: A personal resource linked with well-being and turnover intentions. Educational Psychology, 45(3), 257–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R. J., Sáez-Delgado, E. M., & Granziera, H. (2025). Teachers’ perceived social-emotional competence as a vital mechanism of adult SEL. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy, 5, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, J. M., Cuesta, P., & Cuesta, E. (2023). El impacto psicológico de la Pandemia en los docentes. Un enfoque. Enfermería Global: Revista Electrónica Trimestral de Enfermería, 22(4), 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, P. (2018). La participación en línea en la esfera pública. Las ambigüedades del afecto. Inmediaciones de la Comunicación, 13(1), 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, S. A., Bassett, H. H., & Zinsser, K. (2012). Early childhood teachers as socializers of young children’s emotional competence. Early Childhood Education Journal, 40(3), 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education of the Autonomous Government of the Canary Islands. (2022). Curriculum del Área de Educacion Emocional y para la Creatividad. Available online: https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/boc/2022/231/001.html (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Di Fabio, A. (2015). Beyond fluid intelligence and personality traits in social support: The role of ability based emotional intelligence. Frontiers in Psychology Section Educational Psychology, 6, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extremera, N., & Fernandez-Berrocal, P. (2015). Inteligencia emocional y educacion. Editorial Grupo 5. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Berrocal, P. (2015). TIEFBA, Test de Inteligencia Emocional de la fundacion botin para adolescentes (manual). Fundacion Botin. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Berrocal, P., Extremera, N., & Ramos, N. (2004). Validity and reliability of the Spanish modified version of the trait meta-mood scale. Psychological Reports, 94(3), 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P., & Ruiz, D. (2008). Emotional intelligence in education. Electronic Journal of Research in Educatonal Psychology, 15(2), 421–436. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa, M., & Rodríguez, M. (2023). Análisis de las propiedades psicométricas del cuestionario de competencias socioemocionales SEC-Q en estudiantes universitarios chilenos. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 55, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, B. (2018). Las habilidades socioemocionales, no cognitivas o “blandas”: Aproximaciones a su evaluación. Revista Digital Universitaria (RDU), 19(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L., Iriarte, C., & Reparaz, C. (2019). Attachment ando socio-emotional competences of the teacher. Status of the question 2015–2019. INFAD, 2(1), 119–128. [Google Scholar]

- Garrido, P., & Gaeta, L. (2016). Teacher’s socio-emotional competency pin achieving generic skills the graduate profileinhigher secondary education. Vivat Academia (Alcalá de Henares), 19(137), 108. [Google Scholar]

- Goegan, L., Wagner, A. K., & Daniels, L. M. (2017). Pre-service and practicing teachers’ commitment to and comfort with social emotional learning. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 63(3), 267–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granziera, H., Martin, A. J., & Collie, R. J. (2023). Teacher well-being and student achievement: A multilevel analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 26(2), 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, L. S. (2023). Cambiar la emoción con la emoción. Desclée de Brouwer. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Jorge, C. M., Rodríguez-Hernández, A. F., Kostiv, O., Domínguez-Medina, R., Hess-Medler, S., Capote, M. C., Gil-Frías, P., & Rivero, F. (2021). La escala de evaluación de las competencias emocionales: La perspectiva docente (D-ECREA). Psicología Educativa, 28(1), 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Jorge, C. M., Rodríguez-Hernández, A. F., Kostiv, O., Gil-Frías, P. B., Domínguez Medina, R., & Rivero, F. (2020). Creativity and emotions: A descriptive study of the relationships between creative attitudes and emotional competencies of primary school students. Sustainability, 12(11), 4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivcevic, Z., Brackett, M., & Mayer, D. (2007). Emotional intelligence and emotional creativity. Journal of Personality, 74(2), 199–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. A., Brown, J. L., Frank, J. L., Doyle, S., Oh, Y., Davis, R., & Greenberg, M. T. (2017). Impactos del programa CARE for Teachers en la competencia social y emocional de los maestros y en las interacciones en el aula. Revista de Psicología Educativa, 109(7), 1010. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, D. L., & Newman, D. A. (2010). Emotional intelligence: An integrative meta-analysis and cascading model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khunaivi, H., Kurniasih, E., & Suryati, N. (2023). Social-emotional competence: Empirical evidence from Indonesian pre-service teachers of Islamic elementary education. Al-Bidayah: Journal Pendidikan Dasar Islam, 15(2), 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliewer, W., Borre, A., Wright, A. W., Jaggi, L., Drazdowski, T., & Zaharakis, N. (2016). Parental emotional competence and parenting in low-income families with adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(1), 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, U., Aldrup, K., Roloff, J., Lüdtke, O., & Hamre, B. K. (2022). Does instructional quality mediate the link between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and student outcomes? A large-scale study using teacher and student reports. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(6), 1442–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostiv, O. (2022). El compromiso emocional docente: Validación del constructo y estudio de sus relaciones con otras variables psicoeducativas [Tesis Doctoral, Universidad de La Laguna]. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, M. (2017). Contrastación del modelo de inteligencia emocional de las cuatro ramas [Ph.D. thesis, ULL]. Available online: https://riull.ull.es/xmlui/handle/915/10638 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Machado, Y. (2022). Origen y evolución de la educación emocional. Alternancia—Revista de Educación e Investigación, 4(6), 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A., Ramalho, N., & Morin, E. (2010). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(6), 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Saura, H. F., Sánchez-López, M. C., & Pérez-González, J. C. (2022). Competencia emocional en docentes de infantil y primaria y estudiantes universitarios de los grados de educación infantil y primaria. Estudios Sobre Educación, 42, 9–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, G., Zeidner, M., & Roberts, R. D. (2012). Emotional intelligence: A promise unfulfilled? Japanese Psychological Research, 54(2), 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey, & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Implications for educators (pp. 3–31). Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza, C., & Rueda, C. (2022). Relationship between quality of life and socio-emotional competencies: Systematic review. TECHNO Review, 11(5), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mennes, H., von der Embse, N., Kim, E., Sundar, P., Hines, D., & Welliver, M. (2024). Are “well” teachers “better” teachers? A look into the relationship between first-year teacher emotion and use of evidence-based instructional strategies. School Psychology, 39(3), 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolajczak, M. (2009). Going beyond the ability-trait debate: The three-level model of emotional intelligence. E-Journal of Applied Psychology, 5(2), 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomera, R., Fernández-Berrocal, P., & Brackett, M. A. (2008). La inteligencia emocional como una competencia básica en la formación inicial de los docentes: Algunas evidencias. Electronic journal of research in educational psychology, 6(2), 437–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pertegal-Felices, L., Castejón-Costa, J. L., & Martínez, A. (2011). Socio-emotional competencias of teacher profesional development. Educación XX1, 14(2), 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Petrides, K. V. (2011). Ability and trait emotional intelligence. In T. Chamorro-Premuzic, S. Von Stumm, & A. Furnham (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbook of individual differences (pp. 656–678). Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K. V., & Furnham, A. (2001). Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. European Journal of Personality, 15, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posit Team. (2024). RStudio: Integrated development environment for R [Posit Software]. Available online: http://www.posit.co/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Pozo-Rico, T., Poveda, R., Gutiérrez-Fresneda, R., Castejón, J. L., & Gilar-Corbi, R. (2023). Revamping teacher training for challenging times: Teachers? Well-being, resilience, emotional intelligence, and innovative methodologies as key teaching competencies. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raiche, G., & Magis, D. (2022). nFactors: Parallel analysis and other non graphical solutions to the cattell scree test. R package version 2.4.1.1. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nFactors (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- R Core Team. (2024). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Rodríguez, A. (2018). EducaEMOción. La escuela del corazón. Santillana Activa. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, A. (2022). Emocreatividad o el corazón emocional de la creatividad. Revista Creatividad y Sociedad, 37, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, A. F., & Batista, F. J. (2024). La emoralidad. Una perspectiva psicoeducativa y emocreativa de la relación entre los valores y las emociones. Revista Boletín Redipe, 13(3), 39–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C., Buzón, O., & Marcano, B. (2022). Socio-emotional competence and self-efificacy of future secondary schools teachers. Education Sciences, 12(3), 161. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseel. (2012). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional Intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehnem, H. G., Schneider, C., Güntzel Ramos, M., & Prado, R. M. (2021). La relación profesor-estudiante y su influencia en el proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 20(42), 137–149. [Google Scholar]

- Spanish Mental Health Confederation. (2021). Salud mental y COVID-19: Un año de pandemia. Confederación Salud Mental España. Available online: https://www.consaludmental.org/publicaciones/Salud-mental-covid-aniversario-pandemia.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Teruel, M. P. (2000). La inteligencia emocional en el currículo de la formación inicial de los maestros. RIFOP: Revista interuniversitaria de formación del profesorado: Continuación de la antigua Revista de Escuelas Normales, 38, 141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Trujillo Sáez, F., Fernández Navas, M., Montes Rodríguez, R., Segura Robles, A., Alaminos Romero, F. J., & Postigo Fuentes, A. Y. (2020). Panorama de la educación en España tras la pandemia del COVID-19: La opinión de la comunidad educativa. Fad. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2020). Promoción del bienestar socioemocional de los niños y los jóvenes durante las crisis (p. 7). UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooy, D. L., Viswesvaran, C., & Pluta, P. (2005). An evaluation of construct validity: What is this thing called emotional intelligence? Human Performance, 18(4), 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergaray, R. P., Farfán, J. F., & Reynosa, E. (2021). Educación emocional en niños de primaria: Una revisión sistemática. Revista Científica, Cultura, Comunicación y Desarrollo, 6(2), 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., Buri’c, I., Chang, M.-L., & Gross, J. J. (2023). Teachers’ emotion regulation and related environmental, personal, instructional, and well-being factors: A meta-analysis. Social Psychology of Education, 26(6), 1651–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Mendoza, Y. Y. (2021). Competencias emocionales básicas para profesores en formación. Horizontes. Revista de Investigación en Ciencias de la Educación, 5(19), 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych, I., Marín, I., Fernández, J. L., & García, C. M. (2022). Socially and emtionaly competent teachers: Innovations to promote social an emotional competencies in educacional sciences students. Contextos educativos-Revista de Educación, 29, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Participants | Age | Sex | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sx | Male | Female | Other | |||

| Active teachers | 177 | 42.5 | 12.30 | 40 | 137 | |

| Trainee teachers | 370 | 21.3 | 3.25 | 101 | 268 | 1 |

| Total | 547 | 28.2 | 12.4 | 141 | 405 | 1 |

| Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1. Emotional perception | 0.63 | |||

| 2. Emotional recognition | 0.93 | |||

| 3. Emotional understanding | 0.73 | |||

| 4. Emotional responsibility | 0.48 | 0.55 | ||

| 5. Self-control | 0.70 | |||

| 6. Emotional adjustment | 0.79 | |||

| 7. Emotional recycling | 0.61 | |||

| 8. Empathising | 0.86 | |||

| 9. Emotional communication | 0.51 | |||

| 10. Emotional commitment | 0.66 | |||

| 11. Creative self-confidence | 0.62 | |||

| 12. Openness to change and innovation | 0.66 | |||

| 13. Life entrepreneurship | 0.63 | |||

| Components | Elements | Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s ω |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional awareness | 3 | 0.77 | 0.79 |

| Emotional change | 4 | 0.71 | 0.73 |

| Emotional bonding | 3 | 0.77 | 0.78 |

| Emotional creativity | 3 | 0.66 | 0.67 |

| EE | SE | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Attention | Emotional awareness | 0.675 | 0.266 | 4.243 | <0.001 ** |

| Emotional change | −0.046 | 0.122 | −0.379 | 0.704 | |

| Emotional bonding | 0.632 | 0.179 | 3.530 | <0.001 ** | |

| Emotional creativity | 0.154 | 0.121 | 1.269 | 0.205 |

| EE | SE | T | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2: Clarity | Emotional awareness | 1.028 | 0.282 | 6.080 | <0.001 ** |

| Emotional change | 0.817 | 0.130 | 6.275 | <0.001 ** | |

| Emotional bonding | 0.173 | 0.190 | 0.909 | 0.363 | |

| Emotional creativity | 0.318 | 0.129 | 2.464 | 0.014 * |

| EE | SE | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 3: Repair | Emotional awareness | −0.177 | 0.107 | −1.656 | 0.098 |

| Emotional change | 0.823 | 0.082 | 9.960 | <0.001 ** | |

| Emotional bonding | −0.013 | 0.120 | −0.112 | 0.911 | |

| Emotional creativity | 0.260 | 0.082 | 3.169 | 0.001 ** |

| Teachers | Median | Median | SD | U | p | Rank Correlation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Practicing teachers | 12 | 11.98 | 2.61 | 26,872.5 | 0.001 | −0.179 |

| Trainee teachers | 12 | 11.58 | 1.87 | ||||

| Factor 2 | Practicing teachers | 11 | 11.25 | 2.04 | 30,999.50 | 0.308 | −0.053 |

| Trainee teachers | 11 | 11.03 | 2.15 | ||||

| Factor 3 | Practicing teachers | 12 | 11.35 | 2.40 | 29,859.50 | 0.092 | 0.088 |

| Trainee teachers | 12 | 11.73 | 2.04 | ||||

| Factor 4 | Practicing teachers | 11 | 11.13 | 2.50 | 29,031.50 | 0.031 | −0.113 |

| Trainee teachers | 11 | 10.55 | 2.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez Hernández, A.F.; Hernández-Jorge, C.M.; Delgado Hernández, J. Beyond Emotional Intelligence: Validation of a Model of Emotional Competence Applied to Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091157

Rodríguez Hernández AF, Hernández-Jorge CM, Delgado Hernández J. Beyond Emotional Intelligence: Validation of a Model of Emotional Competence Applied to Teachers. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091157

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez Hernández, Antonio Francisco, Carmen M. Hernández-Jorge, and Jonathan Delgado Hernández. 2025. "Beyond Emotional Intelligence: Validation of a Model of Emotional Competence Applied to Teachers" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091157

APA StyleRodríguez Hernández, A. F., Hernández-Jorge, C. M., & Delgado Hernández, J. (2025). Beyond Emotional Intelligence: Validation of a Model of Emotional Competence Applied to Teachers. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1157. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091157