What Is the Intersection Between Musical Giftedness and Creativity in Education? Towards a Conceptual Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations for Creative Development

2.1. The Conditions for Creativity

[--------Sociocultural Context--------]

2.2. The Domain of Knowledge

The best indicator of giftedness for music is the rate of progress during the first months of learning a task. This means that before the start of formal training it might not be possible, without appropriate tests, to assess with any degree of precision the presence of high aptitudes.(p. 42)

2.3. The Individual as Potential Creator

2.4. The Creative Field

2.5. Creative Actions and Outputs

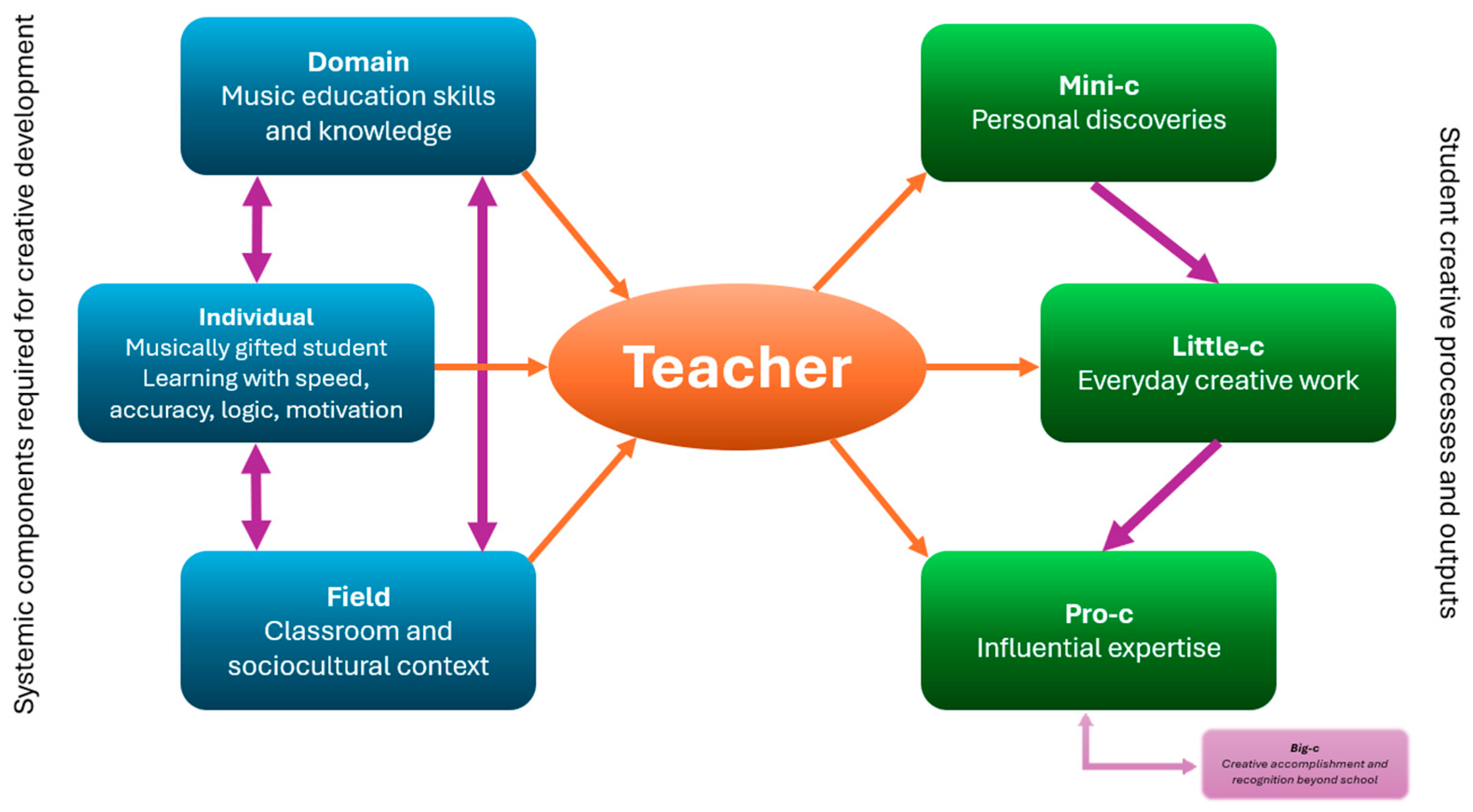

3. A Conceptual Framework for Musical Giftedness and Creativity

3.1. The Intersection of Two Theories

3.2. The Role of the Teacher

3.3. Gifted Education Approaches for Creative Musical Development

3.3.1. Acceleration

3.3.2. Enrichment

3.3.3. Appropriate Instruction

4. Conclusions and Implications

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abramo, J. M., & Natale-Abramo, M. (2020). Reexamining “gifted and talented” in music education. Music Educators Journal, 106(3), 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberger, J. (2013). Cognitive issues in the development of musically gifted children. In J. Bamberger (Ed.), Discovering the musical mind: A view of creativity as learning. Oxford Scholarship Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, M. (2005). A systems view of musical creativity. In D. J. Elliott (Ed.), Praxial music education: Reflections and dialogues (pp. 177–195). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2014). Classroom contexts for creativity. High Ability Studies, 25(1), 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brigandi, C. B., Weiner, J. M., Siegle, D., Gubbins, E. J., & Little, C. A. (2018). Environmental perceptions of gifted secondary school students engaged in an evidence-based enrichment practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 62(3), 289–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooker, R. (1999). Strategies for the education of gifted and talented music students: Acceleration with speed-bumps. In M. S. Barrett, G. E. McPherson, & R. Smith (Eds.), Children and music: Developmental perspectives. ANZARME. [Google Scholar]

- Burnard, P. (2012). Commentary: Musical creativity as practice. In G. E. McPherson, & G. F. Welch (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of music education (Vol. 2, pp. 321–336). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Burnard, P. (2016). Rethinking ‘musical creativity’ and the notion of multiple creativities in music. In O. Odena (Ed.), Musical creativity: Insights from music education research. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, P. S. (2008). Musician and teacher: An orientation to music education. W. W. Norton and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation. (2019). Revisiting gifted education. NSW Department of Education.

- Chaffey, G. W., & Bailey, S. B. (2006). Coolabah dynamic assessment: Identifying high academic potential in at-risk populations. In B. Wallace, & G. Eriksson (Eds.), Diversity in gifted education: International perspectives on global issues (pp. 125–135). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cropley, A. J. (2011). Teaching creativity. In M. A. Runco, & S. R. Pritzker (Eds.), Encyclopedia of creativity (2nd ed., pp. 1–25). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1988). Society, culture, and person: A systems view of creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), The nature of creativity: Contemporary psychological perspectives (pp. 325–339). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., Montijo, M. N., & Mouton, A. R. (2018). Flow theory: Optimizing elite performance in the creative realm. In S. I. Pfeiffer (Ed.), APA handbook of giftedness and talent. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D. Y. (2016). Envisioning a new century of gifted education: The case for a paradigm shift. In D. Ambrose, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Giftedness and talent in the 21st century (pp. 45–63). Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, D. Y., & Chen, F. (2013). Three paradigms of gifted education: In search of conceptual clarity in research and practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 57(3), 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dow, G. T. (2022). Defining creativity. In J. A. Plucker (Ed.), Creativity & innovation: Theory, research, and practice (2nd ed., pp. 5–22). Prufrock Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R. J., Bickel, R., & Pendarvis, E. D. (2000). Musical talent: Innate or acquired? Perceptions of students, parents, and teachers. Gifted Child Quarterly, 44(2), 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evens, M., Elen, J., & Depaepe, F. (2015). Developing pedagogical content knowledge: Lessons learned from intervention studies. Education Research International, 790417, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D. Y. (2012). Gifted and talented education: History, issues, and recommendations. In K. R. Harris, S. Graham, & T. Urdan (Eds.), APA educational psychology handbook: Vol. 2. Individual differences and cultural and contextual factors. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, F. (1995). From giftedness to talent: A developmental model and its impact on the language of the field. Roeper Review, 18(2), 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. (1999). Nature or nuture? A re-examination of Sloboda and Howe’s (1991) interview study on talent development in music. Psychology of Music, 27, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. (2003). Transforming gifts into talents: The DMGT as a developmental theory. In N. Colangelo, & G. A. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of gifted education (3rd ed., pp. 60–74). Allyn and Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Gagné, F., & McPherson, G. E. (2016). Analyzing musical prodigiousness using Gagné’s Integrative Model of Talent Development. In G. E. McPherson (Ed.), Musical prodigies: Interpretations from psychology, education, musicology, and ethnomusicology. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gajda, A., Karwowski, M., & Beghetto, R. A. (2017). Creativity and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(2), 269–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garces-Bacsal, R. M., Cohen, L., & Tan, L. S. (2011). Soul behind the skill, heart behind the technique: Experiences of flow among artistically talented students in Singapore. Gifted Child Quarterly, 55(3), 194–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glăveanu, V. P. (2020). A sociocultural theory of creativity: Bridging the social, the material, and the psychological. Review of General Psychology, 24(4), 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golle, J., Zettler, I., Rose, N., Trautwein, U., Hasselhorn, M., & Nagengast, B. (2018). Effectiveness of a “grass roots” statewide enrichment program for gifted elementary school children. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 11(3), 375–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontijo, C. H. (2018). Mathematics education and creativity: A point of view from the systems perspective on creativity. In N. Amado, S. Carreira, & K. Jones (Eds.), Broadening the scope of research on mathematical problem solving. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5, 444–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, M. H. (2019). Navigating the ideology of creativity in education. In R. A. Beghetto, & G. E. Corazza (Eds.), Dynamic perspectives on creativity. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroutounian, J. (1995). Talent identification and development in the arts: An artistic/educational dialogue. Roeper Review, 18(2), 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroutounian, J. (2000). The delights and dilemmas of the musically talented teenager. The Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 12(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haroutounian, J. (2017). Artistic ways of knowing in gifted education: Encouraging every student to think like an artist. Roeper Review, 39(1), 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, D., Mishra, P., & Capurro, C. T. (2022). A sociocultural perspective on creativity and technology: New synergies for education. In J. A. Plucker (Ed.), Creativity & innovation: Theory, research, and practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P. S. K., & Chong, S. N. Y. (2010). The talent development of a musically gifted adolescent in Singapore. International Journal of Music Education, 28(1), 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvin, L. (2017). Talent development in the world of classical music and visual arts. RUDN Journal of Psychology and Pedagogics, 14(2), 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Johnsen, S. K. (2018). Definitions, models, and characteristics of gifted students. In S. K. Johnsen (Ed.), Identifying gifted students: A practical guide (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, J. L. (2009). A resuscitation of gifted education. American Educational History Journal, 36(1), 37–52. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Katz-Buonincontro, J. (2018). Creativity for whom? Art education in the age of creative agency, decreased resources, and unequal art achievement outcomes. Art Education, 71(6), 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C. (2016). Creativity 101 (2nd ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four C model of creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C., Luria, S. R., & Beghetto, R. A. (2018). Creativity. In S. I. Pfeiffer (Ed.), APA handbook of giftedness and talent (pp. 287–298). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of enrichment programs on gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 60(2), 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, H. (2003). Identifying the gifted in music. Thai National Centre for the Gifted and Talented, Bangkok. [Google Scholar]

- Marek-Schroer, M. F., & Schroer, N. A. (1993). Identifying and providing for musically gifted young children. Roeper Review, 16(1), 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, K., & Young, S. (2015). Musical play. In G. E. McPherson (Ed.), The child as musician: A handbook of musical development. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, G. E. (1997). Giftedness and talent in music. The Journal of Aesthetic Education, 31(4), 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, G. E. (Ed.). (2016). Musical prodigies: Interpretations from psychology, education, musicology, and ethnomusicology. Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, G. E., & Lehmann, A. C. (2012). Exceptional musical abilities: Musical prodigies. In G. McPherson, & G. F. Welch (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of music education (Vol. 2, pp. 31–51). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, G. E., & Williamon, A. (2015). Building gifts into musical talents. In G. McPherson (Ed.), The child as musician: A handbook of musical development (2nd ed., pp. 239–256). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen, C. A. (2019). Creative synthesis: Combining the 4C and systems models of creativity. In C. A. Mullen (Ed.), Creativity under duress in education? Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neihart, M. (2007). The socioaffective impact of acceleration and ability grouping: Recommendations for best practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(4), 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohio Department of Education. (2009). Identification of children who are gifted in music: Implementation handbook for educators. Ohio Department of Education.

- Passow, A. H. (1958). Enrichment of education for the gifted. In N. B. Henry (Ed.), Education for the gifted: Fifty-seventh yearbook of the national society for the study of education, part 1 (pp. 193–221). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Da Costa, M., & Lubart, T. I. (2016). Gifted and talented children: Heterogeneity and individual differences. Annals of Psychology, 32(3), 662–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preckel, F., Schmidt, I., Stumpf, E., Motschenbacher, M., Vogl, K., Scherrer, V., & Schneider, W. (2019). High-ability grouping: Benefits for gifted students’ achievement development without costs in academic self-concept. Child Development, 90(4), 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, K. B. (2007). Lessons learned about educating the gifted and talented: A synthesis of the research on educational practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51(4), 382–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, J. L. (2008). Teaching strategies to facilitate learning for gifted and talented students. The Australian Journal of Gifted Education, 17(2), 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, R. K., & Henriksen, D. (2023). Explaining creativity: The science of human innovation. Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selkrig, M. (2018). Connections teachers make between creativity and arts learning. Educational Research, 60(4), 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavinina, L. V. (2010). What does research on child prodigies tell us about talent development and expertise acquisition? Talent Development & Excellence, 2(1), 29–49. [Google Scholar]

- Simonton, D. K. (2017). Creative geniuses, polymaths, child prodigies, and autistic savants: The ambivalent function of interests and obsessions. In P. A. O’Keefe, & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), The science of interest. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Southern, W. T., Jones, E. D., & Stanley, J. C. (1993). Acceleration and enrichment: The context and development of program options. In K. A. Heller, F. J. Mönks, & A. H. Passow (Eds.), International handbook of research and development of giftedness and talent (pp. 387–409). Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Steenbergen-Hu, S., Makel, M., & Olszewski-Kubilius, P. (2016). What 100 years of research says about the effects of ability grouping and acceleration on K-12 students’ academic achievement: Findings of two second-order meta-analyses. Review of Educational Research, 2(10), 849–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R. J. (2025). Developing creativity in psychological science and beyond. Education Sciences, 15(2), 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subotnik, R. F., Jarvin, L., Thomas, A., & Lee, G. M. (2016). Transitioning musical abilities into expertise and beyond: The role of psychosocial skills in developing prodigious talent. In G. E. McPherson (Ed.), Musical prodigies: Interpretations from psychology, education, musicology, and ethnomusicology. Oxford Scholarship Online. [Google Scholar]

- Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. C. (2011). Rethinking giftedness and gifted education: A proposed direction forward based on psychological science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12(1), 3–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, C. A. (2005). Quality curriculum and instruction for highly able students. Theory Into Practice, 44(2), 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkman, B. (2020). The evolution of the term of giftedness & theories to explain gifted characteristics. Journal of Gifted Education and Creativity, 7(1), 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- VanTassel-Baska, J. (2005). Gifted programs and services: What are the nonnegotiables? Theory Into Practice, 44(2), 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vialle, W., & Rogers, K. B. (2009). Educating the gifted learner. David Barlow Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, C. L., & Mofield, E. L. (2023). Considerations for professional learning supporting teachers of the gifted in pedagogical content knowledge. Gifted Child Today, 46(2), 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegerhoff, D., Ward, T., & Dixon, L. (2022). Epistemic pluralism and the justification of conceptual strategies in science. Theory & Psychology, 32(3), 443–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R. (2021). Effective music teaching in New South Wales: How school music programs promote consistent high achievement in the Higher School Certificate [Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Sydney]. [Google Scholar]

- White, R. (2022). High achievement and the musically gifted: How music educators across New South Wales, Australia develop and extend their most capable students. Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 31(1), 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, V. R., & Laycroft, K. C. (2020). How can we better understand, identify, and support highly gifted and profoundly gifted students? A literature review of the psychological development of high-profoundly gifted individuals and overexcitabilities. Annals of Cognitive Science, 4(1), 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrell, F. C., Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Dixson, D. D. (2019). Gifted students. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 551–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahn, L., & Kaufman, J. C. (2016). Asking the wrong question: Why shouldn’t people dislike creativity? In D. Ambrose, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), Creative intelligence in the 21st century (pp. 75–87). Sense Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Yumatle, C. (2015). Pluralism. In M. T. Gibbons (Ed.), The encyclopedia of political thought (1st ed., pp. 1–20). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Yusoff, S. M., Marzaini, A. F. M., Hassan, M. H., & Zakaria, N. (2023). Investigating the roles of pedagogical content knowledge in music education: A systematic literature review. Malaysian Journal of Music, 12(2), 95–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

White, R. What Is the Intersection Between Musical Giftedness and Creativity in Education? Towards a Conceptual Framework. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091139

White R. What Is the Intersection Between Musical Giftedness and Creativity in Education? Towards a Conceptual Framework. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091139

Chicago/Turabian StyleWhite, Rachel. 2025. "What Is the Intersection Between Musical Giftedness and Creativity in Education? Towards a Conceptual Framework" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091139

APA StyleWhite, R. (2025). What Is the Intersection Between Musical Giftedness and Creativity in Education? Towards a Conceptual Framework. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1139. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091139