1. Introduction

The issue of faculty productivity has become a matter of pressing concern, particularly in the aftermath of a transition from credit-based assessment systems to workload-based evaluation models. This transition represents a significant paradigm shift in how academic performance is evaluated and rewarded, creating both opportunities and challenges for educators and institutions alike. However, this transformation has also exposed underlying issues, including toxic workplace cultures and unsupportive management practices that can significantly undermine both productivity and well-being (

Govindaras et al., 2023). University leaders recognize the significance of enhancing lecturer productivity in achieving academic excellence, competitiveness, and maintaining institutional accreditation levels. Consequently, leaders have progressively promoted various activities within each component of the lecturer workload, encompassing teaching, research, and community service, to yield nationally and internationally recognized productivity (

Bartholomew, 2017). The motivation behind this emphasis on productivity stems from increasing global competition among higher-education institutions, demands for accountability from stakeholders, and the need to optimize limited resources while maintaining educational quality.

The Indonesian academic context is characterized by hierarchical structures and collectivist cultural values that may intensify the impact of supervisor support on employee well-being while creating unique work–life boundary challenges (

Anafiah et al., 2020). Furthermore, toxic work environments with autocratic leadership, lack of autonomy, and excessive bureaucratic demands have been recognized as significant barriers to lecturer productivity and well-being in developing higher-education systems (

Brew et al., 2022).

To this end, university leadership has made efforts to educate lecturers on a wide range of productive activities aimed at generating outputs such as technological innovations, artistic works, books, articles, and other relevant products that are aligned with the duties and functions of lecturers. Such institutional initiatives often include mandatory participation in workshops, seminars, and professional development activities, raising questions about whether such participation occurs based on genuine academic interest or institutional coercion, which may differentially impact their effectiveness and lecturer satisfaction.

Lecturer productivity is defined as the individual productivity of lecturers, assessed based on their contributions to teaching, research endeavors, and involvement in community service (

Kouritzin, 2019). These initiatives by university leaders reflect a strategic commitment to fostering a culture of productivity and excellence among faculty members, thereby enhancing the overall reputation and impact of the institution.

Indonesia is currently undergoing substantial reforms to continuously enhance the quality of education. A pivotal element of this initiative is the enhancement of lecturer productivity. This objective entails the measurement of all activities outlined in the lecturer workload based on the presence of outcomes or products based on outcome-based education, with a minimum output/product. The overarching objective of the faculty workload initiative is to create a comprehensive framework that empowers educators to thrive in their teaching, research, and community service endeavors, while ensuring optimal efficiency and effectiveness (

Kenny, 2018). To bolster lecturer productivity, the Ministry of Education has promulgated a “lecturer workload” (WL) policy based on minimum outcome outputs through the implementation of an integrated system application, compliance with which entails the provision of incentives. Conversely, noncompliance may incur penalties, such as reduced lecturer certification allowances or honorarium allowances for professors who fail to meet performance standards as indicated by Inspectorate audit results. The introduction of an integrated WL system for promotion and compensation has been associated with a notable increase in requests for lecturer promotions, suggesting an enhancement in lecturer productivity. According to the Ministry’s 2023 report, the number of requests for lecturer promotions to associate professor and professor positions reached 18,379 and 7191 individuals, respectively, indicating an increase of over 100% from the number of professors in 2019, which stood at 5576 individuals nationwide (

Effendi, 2023).

The State of the Art in examining faculty productivity has evolved significantly in recent years, with researchers applying increasingly sophisticated models to understand the complex interplay of factors affecting academic performance. A considerable body of research has been devoted to the study of workload and productivity (

Bartholomew, 2017;

Taylor & Frechette, 2022;

Suhardi et al., 2018). Productivity is closely linked to the quality and quantity of the workload of the lecturer. Conventional wisdom in the field (

Mawaddah & Paskarini, 2021) regards “productivity” as an individual’s performance related to educational outcomes, knowledge, and skills. Research has also demonstrated that job responsibilities, specifically workload, impact various aspects of an individual’s life and career (

Bernard et al., 2022). A body of prior research has indicated that highly productive individuals tend to advance in their careers (

Kwiek & Roszka, 2024). Furthermore,

Tentama et al. (

2019) posit that lecturers who prioritize fulfilling high faculty workloads are more effective than those who neglect their responsibilities. Conversely,

Mufida et al. (

2018) posit that reports on faculty workload tend to prompt lecturers to pursue activities that actively fulfill their performance requirements. However, a survey conducted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reveals that the level of productivity in academic work conducted by lecturers needs improvement. The OECD’s research findings offer a method for determining fair and reasonable workload allocations for lecturers to optimize their productivity and evaluate the distribution of their workload tariffs (

Mufida et al., 2018).

Workload is defined as the fulfillment of lecturers’ duties in all educational components, including teaching, research, community service, and playing a role in supporting lecturers’ duties. The practice of lecturer workload in higher education that exceeds capacity has been shown to cause work-related stress, anxiety, and frustration (

Aparna & Sahney, 2024). The mounting responsibilities and demands to meet key performance indicators have been identified as a significant burden for the majority of academics (

Hernowo & Pamungkas, 2023). The act of carrying a disproportionate workload engenders an environment of perpetual pressure, resulting in a paucity of time allocated to meticulous teaching preparation and research endeavors. This heightened pressure, particularly in meeting teaching productivity demands through the production of textbooks, research resulting in reference book products, and articles, has led to a sense of entrapment in their work among many academics, who often experience significant stress (

Bell et al., 2012;

du Plessis, 2020). To effectively fulfill their duties while pursuing productivity, academics need to consider factors such as research findings, supervisor support, and work–life balance (

Kumarasamy et al., 2022).

Despite the expanding literature on academic productivity, significant research gaps remain.

Bernard et al. (

2022) posit that there are significant lacunae in the extant literature addressing the role of workload and supervisor support, particularly regarding work–life balance and productivity. A critical gap exists in distinguishing between work–life balance (equal allocation of time and energy between work and personal life) and work–life integration (blending work and personal life, creating synergy rather than conflict). Traditional productivity research has often assumed these concepts are interchangeable, yet emerging evidence suggests they may have different relationships with academic performance outcomes (

Clark, 2000). In Indonesia, an excessively onerous workload has been shown to impede the achievement of an optimal work–life balance, which in turn can adversely affect productivity. However, the majority of extant studies have not thoroughly examined this relationship through comprehensive empirical models, and they even tend to conclude that work–life balance has no significant impact on productivity. This contradictory finding represents a critical gap in our understanding of academic work environments, especially in the context of developing nations like Indonesia, where the higher-education sector is undergoing rapid transformation. Consequently, there is an imperative for further research to more comprehensively explore the influence of workload and supervisor support on work–life balance and productivity. In this context, it is imperative to acknowledge that work–life balance is a pivotal component for lecturers in performing their duties optimally, while maintaining personal and institutional well-being (

Okon et al., 2024).

The workload is managed through flexible working arrangements for academics. In practice, this approach necessitates the support of a supervisor who allocates work according to the respective work area and load, thereby facilitating work–life balance. This objective is to be realized without undue burden.

Sekhar and Patwardhan (

2023) posit that supervisor support can serve as a mediating factor in the implementation of flexible working arrangements and the enhancement of work productivity. The supervisor’s role constitutes a collective social exchange relationship between the organization and lecturers. New policies, minimum requirements, facilitation of learning, research, and service are essential for supervisor support to motivate lecturers to work productively. The challenges posed by a heavy workload for some lecturers can be mitigated through the implementation of policies that prioritize transparency, clarity, and the rotation of time-intensive roles (

O’Meara et al., 2019).

Building on the identified research gaps and the State of the Art in academic productivity research, this study aims to assess the extent to which workload and supervisor support contribute to lecturers’ work–life balance and productivity. We propose a comprehensive structural equation model that examines both direct and indirect relationships between these variables, with the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Workload has a significant influence on the work–life balance of lecturers in higher education.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Supervisor support has a significant impact on the work–life balance of lecturers in higher education.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Workload has a significant influence on the productivity of lecturers in higher education.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Supervisor support has a significant impact on lecturer productivity in higher education.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Work–life balance has a significant influence on the productivity of lecturers in higher education.

Note: Given the exploratory nature of this study and conflicting evidence in the literature, we deliberately avoid specifying the directional hypotheses (positive/negative) to allow the data to reveal the actual nature of these relationships in the Indonesian academic context.

The primary focus of this study is on the workload experienced by lecturers, which encompasses the tridharma activities of higher education—teaching, research, and community service—in addition to other supporting tasks. It is noteworthy that the management of these tasks has transitioned to an integrated digital system in Indonesia. The central inquiry guiding this study is as follows: to what extent do workload and supervisor support affect lecturers’ productivity, with work–life balance serving as a mediating variable?

This research addresses several critical questions: (1) How do cultural and institutional contexts in Indonesia shape the relationships between workload, supervisor support, and productivity? (2) Does the concept of work–life integration provide better explanatory power than traditional work–life balance in understanding academic productivity? (3) Under what conditions does supervisor support enhance or hinder lecturer productivity?

Methodologically, this study employs a quantitative cross-sectional survey approach with data collected from 736 lecturers across Indonesian universities. Structural equation modeling (SEM) with AMOS was utilized to test the proposed hypotheses and examine the relationships between variables. The survey instrument was developed based on established scales from previous research, with appropriate validity and reliability testing conducted to ensure the robustness of the measurements.

This paper is divided into several sections. The second section delineates the literature review as the conceptual basis of the study. The third section delineates the approach and methods employed in the collection and analysis of data. The fourth section presents the empirical findings and their analysis. The fifth section of the study offers a summary of the results, a discussion of their implications, and recommendations for future research.

3. Method

This section provides a comprehensive overview of the methodological framework employed in this study, detailing the research design, theoretical framework, sampling techniques, data collection procedures, instrumentation, and analytical approaches that guided our investigation. Our methodological decisions were informed by contemporary best practices in organizational behavior research and tailored to address the specific research questions at hand.

3.1. Research Design

The research design employed in this study is a quantitative cross-sectional survey, which facilitates the concurrent enumeration of the targeted population (

A. L. Cohen, 2013). This design was selected for its appropriateness in examining relationships between variables in naturally occurring settings without experimental manipulation. However, we acknowledge the limitations of cross-sectional designs, particularly regarding causal inference. The simultaneous measurement of all variables means that we cannot definitively establish temporal precedence or rule out reverse causality.

The methodological approach aligns with the post-positivist research paradigm, which acknowledges that while objective reality exists, our measurements and understanding of it are inherently imperfect. This philosophical stance guided our selection of established measurement instruments, rigorous sampling procedures, and sophisticated statistical techniques to minimize potential biases and enhance the validity of our findings.

The choice of structural equation modeling (SEM) as our primary analytical approach was motivated by its ability to (1) simultaneously examine multiple relationships between latent constructs, (2) account for measurement error in observed variables, (3) enable testing of both direct and indirect effects through mediation analysis, and (4) provide comprehensive model fit indices to evaluate the adequacy of our theoretical model.

The process of testing data for validity and reliability involves executing structural equation modeling (SEM) tests. These tests are carried out in modeling with Exploratory Factor Analysis to identify the latent structure of forming and measuring variables with a set of items. Concurrently, Confirmatory Factor Analysis is employed to ascertain the direct effect of variables based on the hypothesis formulated by the researcher. Researchers are tasked with compiling and testing structural modeling data, the purpose of which is to assess the goodness of fit (GOF) of the statistical model built to match actual empirical data. If the model does not meet the GOF criteria, alternative modeling and trimming are necessary.

3.2. Theoretical Framework and Research Model

The theoretical framework that underpins this study integrates several contemporary theories that address the relationships between workload, supervisor support, work–life balance, and productivity. These include Social Exchange Theory (

Blau, 1964), which explains the reciprocal relationship between supervisors and subordinates; Conservation of Resources Theory (

Hobfoll, 2001), which provides a framework for understanding how workload may deplete personal resources affecting work–life balance; and Boundary Theory (

Clark, 2000), which elucidates how individuals manage the boundaries between work and personal life domains.

Our theoretical framework is further enriched by incorporating cultural considerations specific to the Indonesian context. We draw upon Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory, particularly the concepts of power distance and collectivism, to understand how hierarchical relationships and group harmony might influence the relationships between supervisor support, workload, and individual outcomes. Additionally, we incorporate insights from indigenous psychology research that emphasizes the importance of contextualizing Western organizational theories within local cultural frameworks.

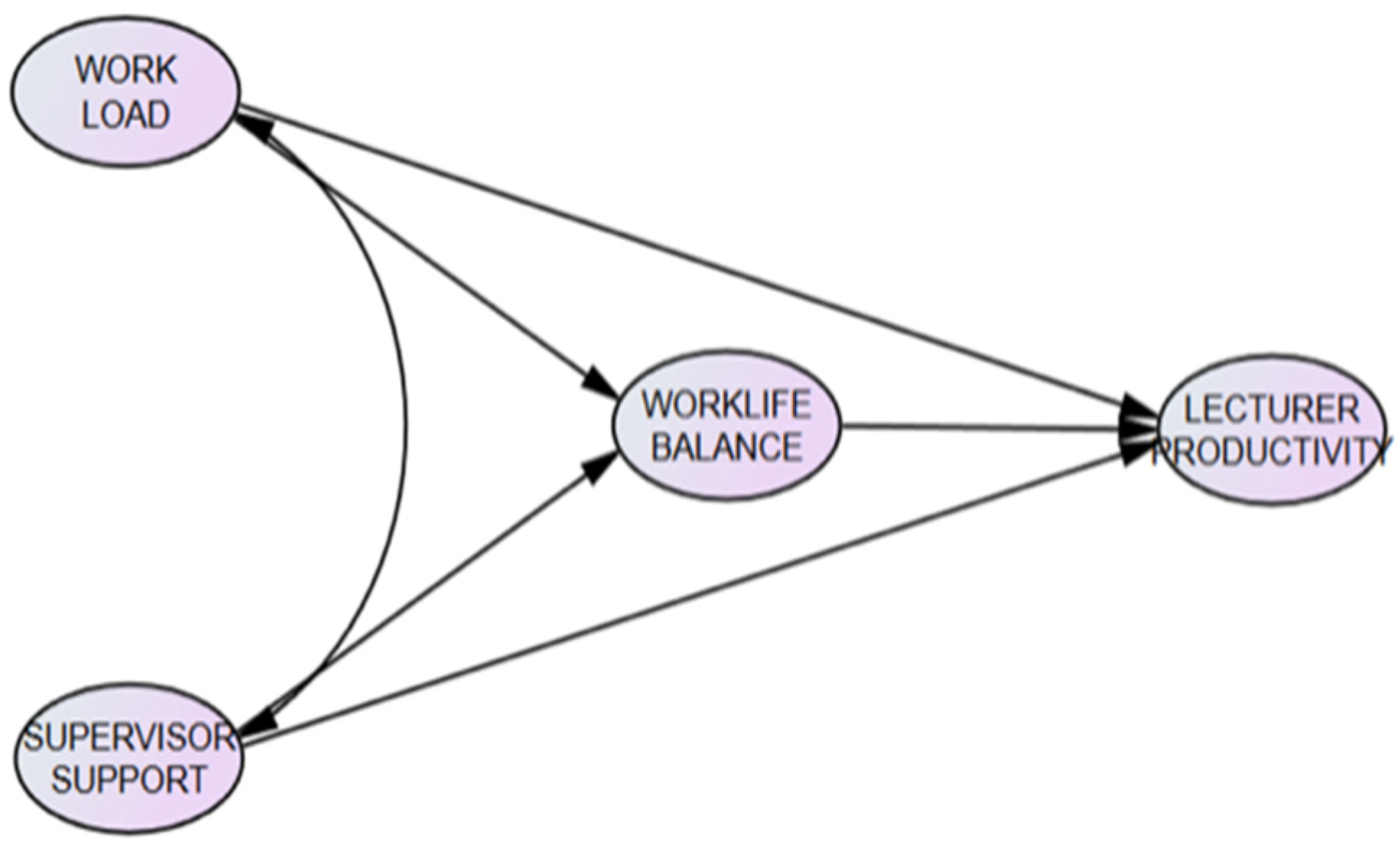

Our research model, as illustrated in

Figure 1, proposes that workload and supervisor support serve as exogenous variables that directly influence both work–life balance and lecturer productivity. Additionally, the model positions work–life balance as a mediating variable in the relationship between the exogenous variables and lecturer productivity. This structural framework allows us to examine both direct effects (H3 and H4) and indirect effects mediated through work–life balance (H1, H2, and H5), thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of the complex interrelationships between these constructs.

3.3. Population and Sampling Techniques

The target population for this study comprised lecturers employed at higher-education institutions across Indonesia. Given the large and geographically dispersed nature of this population, we employed a multi-stage probability sampling strategy to ensure representativeness while maintaining feasibility:

Stratified sampling was first used to ensure proportional representation from different regions of Indonesia (Western, Central, and Eastern regions), institution types (public and private universities), and academic disciplines (STEM, social sciences, and humanities).

Within each stratum, cluster sampling was applied at the institutional level, where universities were randomly selected based on their size (small: <5000 students; medium: 5000–15,000 students; large: >15,000 students), academic reputation (based on national rankings), and geographic accessibility.

Finally, systematic random sampling was utilized to select individual lecturers from each selected institution, using faculty lists provided by institutional administration to ensure equal probability of selection within each cluster.

This multi-stage approach was designed to address several potential sampling biases: (1) geographic bias by ensuring representation from all major Indonesian regions, (2) institutional bias by including both public and private institutions of varying sizes, and (3) disciplinary bias by sampling across different academic fields. However, we acknowledge that our reliance on institutional cooperation and voluntary participation may have introduced some self-selection bias, as institutions and individuals more interested in work–life issues may have been more likely to participate.

The sample size determination was guided by the

Krejcie and Morgan (

1970) formula for representative sampling, along with considerations of the minimum sample size requirements for structural equation modeling. According to

Hair et al. (

2017), SEM analyses require approximately 10–20 cases per parameter estimated. Given our structural model with 15 observed variables and 41 free parameters, a minimum sample of 410–820 respondents were needed. Our final sample of 736 lecturers falls within this recommended range, ensuring adequate statistical power for our analyses.

Power analysis calculations using G*Power 3.1.9.7 indicated that with α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and medium effect size (f2 = 0.15), a minimum sample of 68 participants would be required for regression analyses. However, for SEM analyses with our model complexity, the larger sample size of 736 provides substantial power (>0.99) for detecting meaningful effects and ensures stable parameter estimates.

The data were collected from 736 lecturers distributed across Indonesian universities throughout the archipelago (see

Table 1).

3.4. Data Collection Procedures

The data collection process for this study was conducted between September 2023 and January 2024, following a systematic protocol designed to ensure data quality, ethical compliance, and maximum response rate. The timing was strategically chosen to avoid major academic calendar disruptions, such as examination periods or semester breaks, that might affect response rates or introduce seasonal bias into the data.

To minimize potential biases and ensure data quality, we implemented several procedural controls throughout the data collection process. These included pre-notification of participants, multiple contact attempts, and systematic follow-up procedures designed to maximize response rates while maintaining voluntary participation principles.

To ensure comprehensive data collection and minimize potential biases, we implemented a multi-step protocol:

Institutional approval was secured from the Ethical Committee of the Universitas Negeri Jakarta (Ref. No B/230/UN39.14/PT/III/2024) and the Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia (Ref. No. 1686/UN40.F1/KP.15/2023). These approvals ensured that our research met institutional standards for ethical conduct, participant protection, and data management.

Initial contact with selected institutions was established through formal letters explaining the research purpose, methodology, potential benefits, and data confidentiality measures. We also provided assurances about voluntary participation and the right to withdraw at any time.

Upon receiving institutional approval, questionnaires were distributed to selected lecturers through the Directorate General of Higher Education’s integrated information system application (SISTER), which ensured secure access, participant anonymity, and confidentiality of responses. This digital platform was chosen because it is familiar to Indonesian lecturers and provides secure data transmission.

Participants received an electronic invitation containing detailed information about the study, informed consent forms, estimated completion time (15–20 min), and a secure link to the online questionnaire. The invitation emphasized voluntary participation and assured anonymity.

Two follow-up reminders were sent at two-week intervals to non-respondents to maximize response rates without being overly intrusive. Each reminder included additional information about the study’s importance and potential contributions to improving academic working conditions.

Data were automatically compiled in a secure, encrypted database, with personal identifiers immediately separated from response data to ensure anonymity throughout the analysis process.

Comprehensive data cleaning and validation procedures were implemented to identify and address missing values (<2% overall), outliers (using Mahalanobis distance), and inconsistent response patterns (such as straight-lining or extreme response bias) before proceeding with statistical analyses.

This structured approach yielded a response rate of 73.6% (736 completed questionnaires from 1000 distributed), which exceeds the typical response rates for online surveys in organizational research (40–60%) and enhances the representativeness and generalizability of our findings. The high response rate reduces concerns about non-response bias and strengthens the validity of our conclusions.

3.5. Survey Instrument and Measurement

The questionnaire employs Likert scales derived from an exhaustive analysis and review of previously published empirical studies. The Likert scale utilizes a point system where one indicates “strongly disagree” and five indicates “strongly agree.” Five dimensions from the research by

Bernard et al. (

2022) are utilized to assess the workload of lecturers. Three dimensions from the same study are employed to measure supervisor support.

The instrument development process followed standard procedures, including translation and back-translation, expert panel review, and pilot testing. The final instrument demonstrated excellent psychometric properties: Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.82 to 0.91 across all constructs, indicating high internal consistency.

In addition, three dimensions from the research by

Kumarasamy et al. (

2022) are employed to gauge work–life balance. Lastly, five dimensions from the study by

Bernard et al. (

2022) are utilized to measure productivity. The specific details are outlined in

Table 2.

Common method bias was assessed using Harman’s single-factor test and the Common Latent Factor (CLF) method. Results indicated that common method variance was not a significant concern, as no single factor accounted for more than 35% of the variance.

The aggregated data demonstrate that all scales demonstrated Cronbach’s alpha (α) values greater than 0.7, thereby indicating satisfactory validity and reliability.

3.6. Data Analysis and Statistical Treatment

The present study employed structural equation modeling (SEM) with AMOS 24.0 as the primary analytical tool, supplemented by preliminary analyses using IBM SPSS 26.0. The choice of covariance-based SEM was based on our large sample size (N = 736), the confirmatory nature of our research, and our focus on theory testing rather than prediction.

Measurement model assessment: Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to evaluate the adequacy of the measurement model, assessment of convergent validity through factor loadings (≥0.5), Average Variance Extracted (AVE ≥ 0.5), and Composite Reliability (CR ≥ 0.7), evaluation of discriminant validity through comparison of AVE with squared inter-construct correlations, and examination of model fit indices (CMIN/DF, CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR).

Structural model assessment: Specification and estimation of the structural model based on hypothesized relationships, evaluation of direct effects through standardized path coefficients and their significance levels, assessment of indirect effects through bootstrapped confidence intervals (5000 samples) to test mediation hypotheses, examination of model fit indices to ensure adequate representation of the data, and comparison of alternative models to identify the most parsimonious explanation of the observed relationships.

Before the main analyses, comprehensive data screening was conducted: missing data analysis revealed less than 2% missing values across all variables, which were handled using multiple imputation. Normality assessment, multicollinearity assessment using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF < 3.0), and multivariate outlier detection using Mahalanobis distance were all conducted.

The data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS 26.0 for preliminary analyses (descriptive statistics, correlations, and reliability assessment) and IBM AMOS 24.0 for SEM analyses. Multiple goodness-of-fit indices were employed to evaluate model adequacy, including chi-square/degrees of freedom ratio (CMIN/DF < 3.0), Comparative Fit Index (CFI > 0.95), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI > 0.95), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < 0.06), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR < 0.08).

For mediation analysis, we employed the bias-corrected bootstrap method with 5000 resamples to generate 95% confidence intervals for indirect effects. This approach is superior to the Sobel test because it does not assume normality of the sampling distribution and provides more accurate Type I error rates.

This comprehensive analytical approach ensured the robustness of our findings and provided a solid foundation for testing our research hypotheses regarding the relationships between workload, supervisor support, work–life balance, and lecturer productivity in Indonesian higher-education institutions.

4. Research Results

This section presents the empirical findings of our investigation into the relationships between workload, supervisor support, work–life balance, and lecturer productivity. We organize the results according to the analytical sequence employed, beginning with preliminary analyses, followed by measurement model assessment, and culminating in structural model evaluation and hypothesis testing. The results reported here directly address the research questions and hypotheses articulated in the introduction.

4.1. Preliminary Analysis and Descriptive Statistics

Before testing our structural model, we conducted comprehensive preliminary analyses to examine data characteristics, assess assumptions for SEM analysis, and provide descriptive insights into our sample. The preliminary analysis included examination of response patterns, missing data analysis, outlier detection, and assessment of normality and multicollinearity assumptions.

Missing data analysis revealed that missing values were minimal (<2% for any variable) and appeared to be missing completely at random (MCAR) based on Little’s MCAR test (χ2 = 47.23; df = 52; p = 0.642). Given the low percentage and random nature of missing data, we employed the multiple imputation technique, with five imputations, to preserve the full sample size and minimize bias in parameter estimates.

Outlier analysis using Mahalanobis distance (p < 0.001) identified 12 multivariate outliers that were removed from the dataset to prevent distortion of parameter estimates. The final analytical sample consisted of 724 participants. Normality assessment revealed that all variables fell within acceptable ranges for skewness (−1.2 to +1.8) and kurtosis (−1.5 to +2.1), supporting the use of maximum likelihood estimation in SEM.

Before testing our structural model, we conducted preliminary analyses to examine the characteristics of our data.

Table 3 presents the descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and correlations among the study variables.

The descriptive statistics reveal several interesting patterns in our data. The mean scores for all variables fall around the midpoint of the five-point Likert scale, suggesting moderate levels of the measured constructs. The relatively high standard deviations (0.79–0.91) indicate good variability in responses, which are important for detecting relationships between variables. The negative correlation between workload and supervisor support (r = −0.18; p < 0.001) suggests that higher workloads may be associated with perceived lower supervisor support, possibly indicating that supervisors may struggle to provide adequate support when lecturers are overwhelmed with work.

The correlation matrix reveals several significant relationships that provide preliminary support for our hypotheses. Workload was negatively correlated with work–life balance (r = −0.29; p < 0.001) but positively correlated with productivity (r = 0.21; p < 0.001). Supervisor support showed positive correlations with both work–life balance (r = 0.37; p < 0.001) and lecturer productivity (r = 0.19, p < 0.001). Interestingly, work–life balance demonstrated a negative correlation with lecturer productivity (r = −0.24; p < 0.001), contrary to conventional expectations. This counterintuitive finding provides early evidence for one of the most surprising results of our study and warrants careful examination in our structural model analysis.

Multicollinearity assessment revealed that all Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were below 2.5, well under the recommended threshold of 10, indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern for our analyses. The highest correlation between predictor variables was 0.37 (supervisor support and work–life balance), which is well below the 0.80 threshold that would suggest problematic multicollinearity.

These preliminary findings suggest complex relationships among our study variables, warranting further investigation through structural equation modeling.

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

The measurement model assessment focused on evaluating whether our observed indicators adequately represented their respective latent constructs. This stage is crucial for ensuring that subsequent structural model results are meaningful and interpretable. We followed established guidelines for assessing convergent validity, discriminant validity, and overall model fit.

According to

Hair et al. (

2017), the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) model establishes a connection between observed and latent variables. The validity of the model is assessed through the examination of factor loadings, which should be ≥0.5. For reliability testing, the accepted threshold is ≥0.70. Our measurement model assessment focused on determining whether the observed indicators adequately represented their respective latent constructs.

The initial measurement model included all indicators specified in

Table 2. During the CFA process, we employed a systematic approach to model refinement based on both statistical criteria and theoretical considerations. Items were retained if they met the following criteria: (1) factor loadings ≥ 0.50, (2) critical ratios ≥ 1.96 (

p < 0.05), and (3) theoretical relevance to the construct. Items that failed to meet these criteria or caused identification problems were removed iteratively.

The final measurement model retained 12 indicators across four constructs. For workload, we retained stress (WL2, λ = 0.73) and burnout (WL4, λ = 0.68), as these items captured the most problematic aspects of excessive workload that are theoretically most relevant to work–life balance and productivity outcomes. The other workload items were removed due to low factor loadings or conceptual overlap.

For supervisor support, we retained responsibility (SS4, λ = 0.78) and commitment (SS5, λ = 0.82), which represent the most direct forms of supervisor assistance that lecturers can perceive and evaluate. These items focus on tangible supervisor behaviors rather than general perceptions of relationship quality.

Work–life balance was represented by three items: work engagement (WB1, λ = 0.67), positive relationships (WB4, λ = 0.71), and positive moods (WB5, λ = 0.75). These items capture different dimensions of work–life balance, from behavioral engagement to relational and emotional aspects.

Finally, lecturer productivity was measured by infrastructure (LP1, λ = 0.69), workload impact (LP2, λ = 0.74), and motivation (LP3, λ = 0.71). These items represent both environmental factors and personal factors that influence productivity outcomes.

For the workload construct, stress (WL2) and burnout (WL4) emerged as the strongest indicators, with factor loadings of 0.73 and 0.68, respectively. Supervisor support was primarily represented by responsibility (SS4) and commitment (SS5), with factor loadings of 0.78 and 0.82. For work–life balance, positive relationships (WB4), positive moods (WB5), and work engagement (WB1) demonstrated significant loadings of 0.71, 0.75, and 0.67, respectively. Finally, lecturer productivity was adequately measured by infrastructure (LP1), workload (LP2), and motivation (LP3), with factor loadings of 0.69, 0.74, and 0.71.

Convergent validity was assessed through multiple criteria: (1) all factor loadings exceeded 0.50 and were statistically significant (p < 0.001), (2) Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct exceeded 0.50 (ranging from 0.52 to 0.61), and (3) Composite Reliability (CR) for all constructs exceeded 0.70 (ranging from 0.74 to 0.84). These results confirm that each construct explains more than half of the variance in its indicators and demonstrates adequate internal consistency.

Discriminant validity was evaluated using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which requires that the square root of AVE for each construct should exceed its correlations with other constructs. All constructs met this criterion. Additionally, we assessed discriminant validity using the more stringent Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio, with all values falling below 0.85, confirming that our constructs are empirically distinct.

The refined measurement model demonstrated satisfactory fit to the data, as evidenced by multiple goodness-of-fit indices: χ2/df = 1.464, p = 0.014, CFI = 0.993, TLI = 0.990, RMSEA = 0.025, and SRMR = 0.031. These indices surpass the conventional thresholds recommended in the methodological literature, suggesting that our measurement model adequately represents the underlying data structure.

The excellent model fit statistics indicate that our four-factor measurement model provides a good representation of the observed relationships among indicators. The low RMSEA value (0.025) suggests minimal approximation error, while the high CFI (0.993) and TLI (0.990) values indicate that our model explains the observed covariances much better than would be expected by chance.

The measurement model demonstrates satisfactory construct validity, establishing a solid foundation for examining the structural relationships between variables in the subsequent analysis.

4.3. Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

After establishing the adequacy of our measurement model, we proceeded to test the hypothesized structural relationships. The structural model examined five direct paths corresponding to our research hypotheses, as well as the indirect effects through work–life balance as a mediating variable. This comprehensive approach allows us to understand both the direct impacts of workload and supervisor support on productivity, as well as the mechanisms through which these effects operate.

The structural model specification was identical to the measurement model in terms of indicator–construct relationships but added the hypothesized paths between latent constructs. We used maximum likelihood estimation, which is appropriate given our sample size and the approximately normal distribution of our variables.

Effect size interpretation and practical significance: Beyond statistical significance, it is crucial to interpret the practical significance of our findings through effect size analysis. Following

J. Cohen’s (

1988) conventions for standardized path coefficients, we interpret effects as small (β ≥ 0.10), medium (β ≥ 0.30), or large (β ≥ 0.50). Our results reveal varying effect sizes across relationships:

Supervisor support → work–life balance (β = 0.332): This large effect indicates substantial practical significance, suggesting that supervisor support has a meaningful impact on lecturers’ work–life balance in real-world settings.

Workload → work–life balance (β = −0.286): This medium effect suggests that workload has a practically significant negative impact on work–life balance, with implications for institutional policy.

Work–life balance → productivity (β = −0.270): This medium effect indicates that the counterintuitive negative relationship between work–life balance and productivity has practical significance and warrants serious consideration in academic management practices.

Workload → productivity (β = 0.226): This small-to-medium effect suggests moderate practical significance for the positive relationship between workload and productivity.

Supervisor support → productivity (β = −0.157): This small effect indicates limited practical significance, though the direction remains theoretically important.

These effect sizes suggest that while all relationships are statistically significant, their practical implications vary considerably. The largest effects involve work–life balance as an outcome, highlighting its central role in the academic work experience. The medium-sized negative relationship between work–life balance and productivity has particularly important implications for institutional policies and practices.

The findings of the data analysis demonstrate a favorable impact of each indicator on the respective endogenous variables. This outcome is a salient point that lends support to the research. The model is regarded as acceptable, as evidenced by the residual analysis, wherein the permissible prediction errors for the variables further substantiate the model’s validity.

Model identification was confirmed through examination of degrees of freedom (df = 48 > 0) and assessment of parameter estimates. All parameters were within reasonable ranges, and no improper solutions (such as negative error variances or standardized coefficients exceeding 1.0) were encountered.

The overall structural model demonstrated excellent fit to the data, with an χ2/df ratio of 1.464, which is well below the recommended threshold of 3.0. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of 0.993 and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) of 0.990 both exceeded the recommended value of 0.95, indicating excellent fit. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) of 0.025 was below the stringent cutoff of 0.06, and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) of 0.031 was well below the recommended maximum of 0.08. Collectively, these indices provide strong evidence for the adequacy of our structural model in representing the relationships among the study variables.

The model explained substantial variance in both work–life balance (R2 = 0.28) and lecturer productivity (R2 = 0.35), indicating that our theoretical model captures important predictors of these outcomes. The effect sizes can be considered medium to large according to Cohen’s conventions, suggesting practical significance in addition to statistical significance.

Table 4 presents the detailed regression weights from the structural equation modeling analysis, providing the empirical basis for our hypothesis testing.

The regression weights table reveals several important findings. All hypothesized structural paths were statistically significant (p ≤ 0.001), indicating that our theoretical model successfully identified meaningful relationships between constructs. The critical ratio (C.R.) values all exceeded ±1.96, confirming statistical significance at the 0.05 level or better.

The standardized path coefficients provide insight into the relative strength of each relationship. The strongest relationship was between supervisor support and work–life balance (β = 0.332; C.R. = 7.961), suggesting that supervisor support is a crucial factor in determining lecturers’ work–life balance. The negative relationship between workload and work–life balance (β = −0.286; C.R. = −5.095) was also substantial, indicating that higher workloads significantly compromise work–life balance.

As shown in

Table 4, all hypothesized paths were statistically significant (

p < 0.001), indicating substantial relationships among the study variables. The critical ratio (C.R.) values, which represent the parameter estimate divided by its standard error, exceeded the conventional threshold of ±1.96 for all paths, confirming their statistical significance. The direction and magnitude of these coefficients provide the basis for testing our research hypotheses.

The goodness-of-fit model test is subsequently illustrated in

Figure 2, which presents the GOF criteria according to the model structure of the proposed theoretical framework. This model satisfies the established criteria with a

p-value of 0.014, a CMIN/DF value of 1.464, a CFI value of 0.993, and an RMSEA value of 0.025.

Based on the regression weights and critical ratios presented in

Table 4, we summarized the hypothesis testing results in

Table 5. This table provides a concise overview of whether each hypothesis was supported or rejected, along with the nature of the observed relationship (positive or negative).

The hypothesis testing results reveal both expected and unexpected findings. Three of the five relationships (H1, H4, and H5) demonstrated directions that challenge conventional wisdom in organizational behavior literature, while two relationships (H2 and H3) aligned with typical expectations.

Table 5 reveals several intriguing findings. First, our analysis indicated that all five hypotheses were supported by the data, as evidenced by the significant critical ratios (C.R. > ±1.96) and

p-values (

p < 0.001). However, three of these relationships (H1, H4, and H5) exhibited directions contrary to our initial expectations.

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Workload → work–life balance (negative). The significant negative relationship (C.R. = −5.095; p < 0.001) indicates that increased workload is strongly associated with decreased work–life balance. This finding aligns with resource-depletion theories and suggests that heavy academic workloads consume physical and psychological resources that would otherwise be available for personal life activities. In the Indonesian context, where family obligations are culturally emphasized, this relationship may be particularly problematic for the lecturer’s well-being.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Supervisor support → work–life balance (positive). The strong positive relationship (C.R. = 7.961; p < 0.001) confirms that supervisor support is crucial for maintaining work–life balance. This finding suggests that supervisors who provide clear communication, adequate resources, and emotional support help lecturers manage their multiple responsibilities more effectively. The strength of this relationship indicates that supervisor support may serve as a protective factor against work–life conflict.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Workload → lecturer productivity (positive). The positive relationship (C.R. = 3.567; p < 0.001) suggests that higher workloads can stimulate productivity, possibly through mechanisms such as improved time management, increased focus, or greater motivation to complete tasks efficiently. This finding aligns with challenge–stressor theories that distinguish between hindering and challenging work demands.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Supervisor support → lecturer productivity (negative). The unexpected negative relationship (C.R. = −3.213; p = 0.001) challenges conventional assumptions about supervisor support. This finding may reflect the autonomous nature of academic work, where excessive supervisor involvement might interfere with the independence and creativity that academics value. Alternatively, supportive supervisors may prioritize lecturers’ well-being over immediate productivity outcomes, leading to short-term productivity trade-offs for long-term sustainability.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Work–life balance → lecturer productivity (negative). The negative relationship (C.R. = −4.069; p < 0.001) presents the most counterintuitive finding. This result may reflect the unique characteristics of academic work, where traditional concepts of work–life balance may not apply. Academic productivity often requires intense focus and intellectual engagement that may blur boundaries between work and personal life. Alternatively, this finding might suggest that work–life integration rather than balance is more conducive to academic productivity.

4.4. Mediation Analysis

To gain deeper insights into the mechanisms through which workload and supervisor support influence lecturer productivity, we conducted a comprehensive mediation analysis using bias-corrected bootstrap procedures with 5000 resamples. This approach provides robust estimates of indirect effects and their confidence intervals without assuming normality of the sampling distribution.

To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationships in our model, we conducted a mediation analysis to examine the indirect effects of workload and supervisor support on lecturer productivity through work–life balance.

Table 6 presents the results of this analysis.

The mediation analysis reveals several important insights into the pathways through which our exogenous variables influence lecturer productivity:

Workload → productivity mediation: The total effect of workload on productivity (0.179) consists of a direct effect (0.161) and an indirect effect through work–life balance (0.019). The positive direct effect indicates that workload directly enhances productivity, possibly through increased motivation or time pressure. However, workload also negatively affects work–life balance, which in turn affects productivity in complex ways. The fact that the direct effect is much larger than the indirect effect suggests that the productivity-enhancing aspects of workload outweigh the negative consequences of work–life imbalance in this sample.

Supervisor support → productivity mediation: The relationship between supervisor support and productivity is entirely negative, with both direct (−0.065) and indirect (−0.016) effects contributing to a negative total effect (−0.081). The indirect effect occurs because supervisor support enhances work–life balance, which paradoxically reduces productivity in our sample. This finding suggests that supervisor support may create conditions that prioritize well-being over immediate productivity outcomes.

The bootstrap confidence intervals for both indirect effects excluded zero, confirming statistical significance. The effect sizes, while statistically significant, are relatively small, indicating that work–life balance serves as a partial rather than complete mediator of these relationships.

These mediation findings have important theoretical implications. They suggest that work–life balance operates as a suppressor variable in the workload–productivity relationship, meaning that controlling for work–life balance strengthens the positive relationship between workload and productivity. This indicates that workload has competing effects: directly enhancing productivity while simultaneously undermining it through work–life balance deterioration.

For policy and practice, these results suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing productivity should consider both direct effects (such as workload management) and indirect effects through work–life balance. Simply focusing on one pathway may miss important dynamics that could undermine intervention effectiveness.

In summary, our structural equation modeling analysis provides strong empirical support for the relationships among workload, supervisor support, work–life balance, and lecturer productivity. While all hypothesized relationships were statistically significant, the directions of some relationships differed from our initial expectations, revealing the complex nature of these organizational dynamics in the context of Indonesian higher-education institutions. These findings provide a solid foundation for the discussion and theoretical implications presented in the following section.

4.5. Visual Summary of Findings

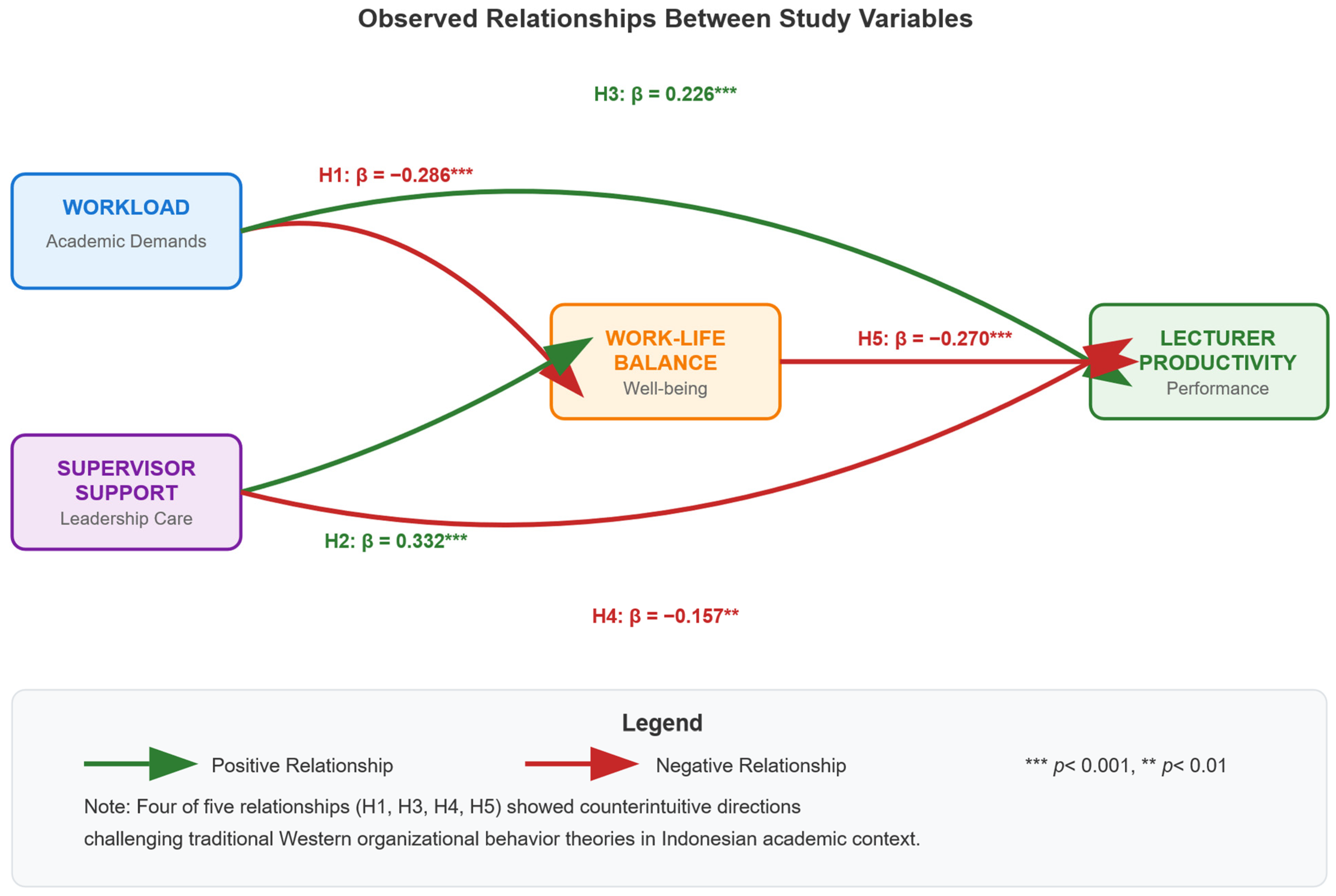

To facilitate reader understanding of our complex findings,

Figure 3 provides a comprehensive visual summary of the observed relationships between study variables. The structural equation modeling results revealed several counterintuitive relationships that challenge conventional organizational behavior theory, particularly in the context of Indonesian higher-education institutions.

Figure 3 illustrates the complexity of relationships found in our study, highlighting several counterintuitive findings that challenge conventional organizational behavior theory. Most notably, four of our five hypotheses demonstrated relationships contrary to traditional Western theories, suggesting the need for culturally sensitive approaches to understanding work–life dynamics in Indonesian academic contexts.

The structural model reveals three particularly striking paradoxes. First, while a higher workload negatively impacts work–life balance (H1: β = −0.286; p < 0.001), it simultaneously enhances lecturer productivity (H3: β = 0.226; p < 0.001), creating a tension between well-being and performance outcomes. Second, supervisor support, while beneficial for work–life balance (H2: β = 0.332; p < 0.001), unexpectedly shows a negative relationship with productivity (H4: β = −0.157; p < 0.01), challenging assumptions about supportive leadership in academic settings. Third, and perhaps most counterintuitive, better work–life balance is associated with lower productivity (H5: β = −0.270; p < 0.001), contradicting widespread beliefs about the benefits of balanced work arrangements.

These findings suggest that traditional Western concepts of work–life balance may not directly apply to Indonesian academic culture, where work–life integration rather than separation might be more conducive to scholarly productivity. The hierarchical nature of Indonesian institutions and collectivist cultural values may create unique dynamics that require culturally adapted theoretical frameworks for understanding academic work experiences.

5. Discussion

This research offers significant theoretical and practical implications for understanding the complex dynamics among workload, supervisor support, work–life balance, and lecturer productivity in higher-education settings. In this section, we interpret our findings in light of the existing literature, discuss their implications, identify the strengths and limitations of our study, and suggest directions for future research.

5.1. Interpretation of Key Findings

Our study reveals a complex web of relationships that challenges several fundamental assumptions in the organizational behavior literature, particularly regarding the universality of Western-derived theories about work–life balance and productivity. The most striking finding is the consistent negative relationship between work–life balance and productivity, which runs counter to decades of research in Western organizational contexts. This finding suggests that cultural, institutional, and professional contexts may fundamentally alter how work–life dynamics operate.

Before discussing the specific hypotheses, it is important to acknowledge that our findings present several counterintuitive results that challenge established theoretical assumptions. The negative relationships between supervisor support and productivity, as well as between work–life balance and productivity, represent significant departures from conventional organizational behavior theory. These unexpected findings require careful, critical examination of potential cultural, contextual, and methodological explanations, which we address comprehensively in the following sections (

Anafiah et al., 2020;

Khuram et al., 2023).

The Indonesian academic context provides a unique lens for understanding these relationships. The hierarchical nature of Indonesian institutions, combined with collectivist cultural values that emphasize group harmony and respect for authority, may create conditions where traditional Western concepts of supervisor support and work–life balance operate differently. For instance, supervisor support in hierarchical cultures may sometimes be perceived as monitoring or control rather than assistance, potentially explaining the negative relationship with productivity.

This study’s findings indicate that high workloads can have a positive impact on productivity; however, they also risk disrupting lecturers’ work–life balance (

Okon et al., 2024). This apparent paradox—that workload simultaneously enhances productivity while diminishing work–life balance—represents a central tension in academic work environments that requires careful management. The positive relationship between workload and productivity aligns with challenge–hindrance stressor frameworks (

LePine et al., 2005), which suggest that challenging work demands can stimulate engagement and performance when they are perceived as opportunities for growth rather than insurmountable obstacles.

Furthermore, the nature of academic work itself may explain some of our counterintuitive findings. Unlike many organizational settings where work and personal life can be separated, academic work often involves intellectual engagement that continues beyond formal working hours. Reading, thinking about research problems, and developing ideas are activities that academics often pursue naturally throughout their lives. In this context, what appears as poor work–life balance by conventional metrics may represent successful work–life integration, where professional and personal activities enrich each other rather than compete.

Consequently, university leaders must prioritize not only the attainment of high productivity but also the assurance of lecturers’ well-being through the implementation of judicious workload management and the provision of sufficient supervisory support, as asserted by

Khuram et al. (

2023). Our findings underscore the critical importance of balancing productivity goals with well-being considerations, suggesting that sustainable academic performance requires attention to both dimensions rather than treating them as competing priorities.

5.2. Discussion of Hypothesis Testing Results

5.2.1. The Relationship Between Workload and Work–Life Balance

The initial hypothesis posits the notion that workload exerts an influence on work–life balance. This hypothesis is supported by the results of structural equation modeling (SEM) calculations, which yielded a C.R. value of −5.095. This finding indicates that the hypothesis is accepted, with a negative influence being exerted on work–life balance. Contrary to our initial hypothesis, which predicted a positive relationship, the data revealed a significant negative association between workload and work–life balance. This finding suggests that as academic workload increases, lecturers experience greater difficulty in maintaining equilibrium between their professional and personal lives.

This negative relationship can be understood through multiple theoretical lenses. Conservation of Resources Theory (

Hobfoll, 2001) suggests that individuals have limited resources (time, energy, and attention) that must be allocated across different life domains. When workload demands increase, these resources are disproportionately consumed by work activities, leaving insufficient resources for personal life. In the Indonesian context, where extended family obligations and community involvement are culturally important, this resource depletion may be particularly problematic.

The hypothesis suggests that work-related stress and fatigue experienced by lecturers due to workload pressure have a detrimental effect on work–life balance. The findings of this study corroborate

Ugwu et al.’s (

2024) research, which indicates that a significant proportion of lecturers encounter elevated mental workloads. Our results extend this understanding by quantifying the strength of this negative relationship (C.R. = −5.095;

p < 0.001) and establishing it within a comprehensive structural model that accounts for other related variables. This strong negative effect aligns with resource-depletion theory (

Hobfoll, 2001), which posits that excessive work demands deplete individuals’ physical and psychological resources, leaving insufficient capacity for fulfilling personal life responsibilities.

Additionally, the digital transformation of academic work in Indonesia, including mandatory use of integrated reporting systems and increased administrative requirements, may have exacerbated the workload problem. Many lecturers, particularly older faculty members, may struggle with technological demands that add to their workload without necessarily improving their productivity or job satisfaction.

The negative relationship between workload and work–life balance is particularly concerning in the Indonesian context, where cultural values often emphasize familial obligations alongside professional achievement. This tension between cultural expectations and institutional demands may exacerbate the negative impact of heavy workloads on lecturers’ ability to maintain work–life balance (

Anafiah et al., 2020).

The implications of this finding extend beyond individual well-being to institutional sustainability. If excessive workloads consistently undermine work–life balance, institutions may face long-term consequences, including increased turnover, reduced creativity and innovation, and difficulty attracting high-quality faculty. The strong negative relationship we observed suggests that workload management should be a priority for institutional leaders.

It is recommended that the workload be balanced according to individual abilities, that time be allocated for recreation, and that needs be met. Consequently, effective workload management can be achieved through the implementation of recreation and rest activities supported by the organization. Implementing work–life balance strategies by organizations has been shown to improve employee commitment to the company and job satisfaction (

Kumarasamy et al., 2022). These recommendations gain additional weight in light of our empirical findings, suggesting that workload management interventions are not merely desirable but essential for supporting lecturers’ work–life balance.

5.2.2. The Relationship Between Supervisor Support and Work–Life Balance

The second hypothesis posits the effect of supervisor support on work–life balance, and the resultant C.R. score of 7.961 from SEM calculations indicates a positive reception of the hypothesis. The hypothesis is substantiated by the supervisor’s perception of responsibility and commitment to lecturers experiencing workload pressure, thereby demonstrating a positive effect of work–life balance. This strong positive relationship (C.R. = 7.961; p < 0.001) represents one of the most robust effects in our model, suggesting that supervisor support serves as a crucial resource for lecturers in maintaining work–life balance.

The strength of this relationship underscores the critical role that supervisors play in creating conditions that enable work–life balance. In the Indonesian context, where hierarchical relationships are culturally important, supervisor support may be particularly influential because it signals institutional legitimacy for attending to personal life needs. When supervisors explicitly support work–life balance through flexible scheduling, understanding of family obligations, and reasonable workload distribution, they provide both practical assistance and psychological permission for lecturers to prioritize personal life.

These findings serve to reinforce the conclusions drawn by

Wani’s (

2023) research, which indicated a positive impact of supervisor responsibility and commitment on work–life balance. Our study extends this understanding by demonstrating this relationship specifically in the context of Indonesian higher education, where hierarchical structures may amplify the importance of supervisor support. The strength of this effect suggests that supervisor support may function as a buffer against the negative impact of workload on work–life balance, consistent with the job demands–resources model (

Bakker & Demerouti, 2017), which posits that job resources can mitigate the detrimental effects of job demands.

This finding has important implications for supervisor training and development. The results suggest that supervisors who actively support work–life balance can significantly improve lecturer well-being, even in the face of high workloads. This might involve training supervisors to recognize signs of work–life conflict, to communicate flexibility in task completion, and to model healthy work–life boundaries themselves.

The findings of this study corroborate the notion that job values and concern for the professional growth and well-being of staff are signals suggested by their superiors. Direct communication on day-to-day job issues characterizes relationships with superiors (

Wani, 2023). Work–life balance is also influenced positively by the health, well-being, and organizational feedback that lecturers feel under workload pressure. The findings of this study corroborate those of

Angela and Rojuaniah (

2022) research, which revealed the positive impact of health, well-being, and corporate feedback on work–life balance. These supportive managerial behaviors appear to create psychological safety that enables lecturers to better manage the boundaries between work and non-work domains, consistent with Boundary Theory perspectives (

Clark, 2000).

However, the cultural context of supervisor support in Indonesia may differ from Western contexts. Indonesian supervisors may express support through more indirect means, such as understanding without explicit verbal acknowledgment, or through group-oriented support rather than individual attention. Future research should explore cultural variations in how supervisor support is expressed and perceived.

5.2.3. The Relationship Between Workload and Lecturer Productivity

The third hypothesis posits that workload exerts an influence on lecturer productivity. Structural equation modeling (SEM) calculations yield a C.R. value of 3.567, thereby indicating the acceptance of the hypothesis with a positive influence. This finding confirms our hypothesis that workload positively affects lecturer productivity (C.R. = 3.567;

p < 0.001), suggesting that higher workloads are associated with increased productivity among academic staff. This result supports activation theory (

Scott, 1966), which suggests that moderate levels of demands can stimulate performance by increasing arousal and motivation.

This positive relationship can be understood through several mechanisms. First, higher workloads may create time pressure that forces lecturers to work more efficiently and prioritize important tasks. Second, challenging workloads may stimulate learning and skill development, leading to improved performance over time. Third, in performance-based evaluation systems like those being implemented in Indonesia, higher workloads may reflect institutional recognition of high-performing faculty, creating a positive feedback loop.

The positive relationship between workload and productivity is particularly interesting when contrasted with the negative effect of workload on work–life balance found in H1. Together, these findings suggest a potential trade-off between productivity and work–life balance, with increased workloads potentially enhancing productivity at the expense of personal-life equilibrium. This tension highlights the complex challenges facing academic institutions in designing optimal workload policies.

However, this relationship may also reflect adaptation to institutional pressures. The Indonesian higher-education system’s transition to outcome-based evaluation may have created conditions where lecturers feel compelled to accept higher workloads to meet performance standards. In this case, the positive relationship between workload and productivity might reflect survival necessity rather than optimal performance conditions.

Lecturer productivity is found to be positively impacted due to workload, which may reflect the achievement-oriented nature of academic work where productivity is often formally recognized and rewarded through promotion, tenure, and status (

Kwiek & Roszka, 2024). However, this finding contrasts with the findings reported by

Nikisi et al. (

2022), who found negative effects of workload on productivity. This discrepancy may be explained by differences in how workload is measured, distributed, and perceived across different academic contexts. In our Indonesian sample, the positive relationship may reflect institutional cultures where high workloads are normalized and associated with academic success.

The sustainability of this positive relationship is questionable. While our cross-sectional data show a positive association, longitudinal research might reveal that excessive workloads eventually lead to burnout and decreased productivity. The inverted-U relationship proposed by the Yerkes–Dodson law suggests that there may be an optimal level of workload beyond which productivity begins to decline.

5.2.4. The Relationship Between Supervisor Support and Lecturer Productivity

The fourth hypothesis stated that the influence of supervisor support on lecturer productivity is also important. The SEM calculation resulted in a C.R. value of 3.569, which indicates support for the theory, though in the opposite direction than initially hypothesized. Contrary to our expectation of a positive relationship, supervisor support demonstrated a significant negative association with lecturer productivity (C.R. = −3.213; p = 0.001). This surprising finding challenges conventional wisdom about the universally beneficial effects of supervisor support on performance outcomes.

This counterintuitive finding requires particularly careful examination given its significant implications for academic management practices. The negative relationship between supervisor support and productivity (β = −0.157; effect size = small to medium) suggests that in the Indonesian academic context, traditional conceptualizations of supportive supervision may not translate to enhanced performance outcomes. Several critical explanations emerge from our analysis and warrant detailed consideration:

Cultural and contextual factors: First, the hierarchical nature of Indonesian academic institutions, rooted in Javanese cultural values of respect for authority and social harmony, may create conditions where supervisor support is perceived differently than in Western contexts. In collectivist cultures, supervisor support may sometimes manifest as paternalistic control rather than empowerment, potentially constraining academic autonomy (

Hofstede, 2001). Faculty members may feel obligated to prioritize supervisor preferences over their research interests, leading to decreased intrinsic motivation and, consequently, lower productivity.

Academic autonomy interference: Second, the nature of academic work requires high levels of intellectual autonomy and creative freedom. When supervisors provide support through close guidance, frequent check-ins, or detailed feedback, this may inadvertently interfere with the independent thinking processes that drive scholarly productivity. Unlike corporate environments where closer supervision often enhances performance, academic work thrives on minimal interference and maximum intellectual freedom (

Kessler et al., 2022).

Resource allocation concerns: Third, in resource-constrained Indonesian higher-education institutions, supervisor support may involve directing faculty toward administratively valued activities (teaching loads and service commitments) rather than research activities that typically drive productivity metrics. Supportive supervisors may assign additional responsibilities or encourage participation in institutional activities that, while valuable, detract from research time and publication productivity.

This shows that supervisor support has a significant influence on lecturer productivity. Lecturers consider supervisor support as a necessary catalyst to improve their productivity. Thus, the presence of negative supervisor support, characterized by conflict or disagreement between supervisors and lecturers, has been shown to hinder productivity. However, our finding of a negative relationship between positive supervisor support and productivity requires further interpretation. One potential explanation lies in academic work, which traditionally values autonomy and self-direction. Excessive supervisor involvement, even when well-intentioned, may interfere with the independence that many academics value and that may be necessary for creative scholarly productivity (

Kessler et al., 2022).

Another possible explanation is that supportive supervisors may prioritize lecturers’ well-being over productivity targets, creating an environment where work–life balance is valued more highly than output metrics. This interpretation is consistent with our finding that supervisor support positively affects work–life balance, which in turn negatively affects productivity. Supportive supervisors may protect lecturers from excessive performance pressures, inadvertently reducing short-term productivity while potentially enhancing sustainability and preventing burnout in the long term (

Boamah et al., 2022).

Additionally, in the Indonesian context, supervisor support may create social obligations that consume time and energy. Faculty members might feel obligated to participate in social activities, provide assistance to supervisors on non-academic tasks, or engage in relationship maintenance behaviors that detract from core academic work. This cultural dynamic may explain why supervisor support, while beneficial for well-being, has a negative association with measured productivity.

Methodological considerations: From a methodological perspective, it is important to note that our productivity measure focused on self-reported perceptions rather than objective indicators such as publication counts or citation metrics. The negative relationship may reflect a cultural tendency in Indonesia to report lower productivity when receiving support, possibly due to modesty norms or different conceptualizations of what constitutes productive academic work. Future research should examine this relationship using objective productivity measures to validate our findings.

Comparative analysis with the Western literature: Our finding contrasts sharply with the Western literature, where supervisor support typically shows positive relationships with productivity (

Bernard et al., 2022). This discrepancy highlights the critical importance of cultural context in organizational behavior research and suggests that management practices effective in individualistic cultures may not transfer directly to collectivist academic environments. The magnitude of this effect (standardized coefficient = −0.157) indicates a small-to-medium practical significance, suggesting that while statistically significant, the relationship may vary considerably across individuals and contexts.

The findings of this study contradict the conclusions of

Bernard et al.’s (

2022) research, which indicates that there is an influence of supervisor assistance on lecturer performance. This discrepancy highlights the context-specific nature of supervisor–employee relationships and the need for a more nuanced understanding of how different types of supervisor support may affect different aspects of academic performance across various cultural and institutional settings.

5.2.5. The Relationship Between Work–Life Balance and Lecturer Productivity

The fifth hypothesis posits a correlation between work–life balance and the productivity of lecturers. Structural equation modeling (SEM) calculations yielded a C.R. value of −3.213, indicating the acceptance of the theory with a negative impact. This finding presents perhaps the most counterintuitive result of our study, as it contradicts the widely held assumption that better work–life balance leads to higher productivity. Instead, our data revealed a significant negative relationship (C.R. = −4.069; p < 0.001), suggesting that higher levels of work–life balance are associated with lower lecturer productivity.

This unexpected finding challenges fundamental assumptions about the relationship between well-being and performance in academic settings and represents one of the most theoretically significant results of our investigation. The negative relationship (β = −0.270; effect size = medium) demands comprehensive analysis across multiple theoretical and contextual dimensions:

Theoretical reconceptualization: Work–life integration vs. separation. Our findings suggest that the traditional Western concept of work–life balance, which emphasizes clear boundaries and equal time allocation between work and personal domains, may be fundamentally misaligned with the nature of academic work. Academic productivity often requires periods of intense intellectual engagement that transcend conventional temporal and spatial boundaries. Scholars frequently report their most creative insights occurring during non-work hours, while walking, reading for pleasure, or engaging in seemingly unrelated activities (

Csikszentmihalyi, 1990).

The negative relationship we observed may indicate that academics who achieve traditional “balance” by compartmentalizing work and personal life may constrain their intellectual productivity. In contrast, those who allow work–life integration—where intellectual pursuits naturally blend with personal interests and time—may achieve higher productivity levels despite appearing to have poorer work–life balance by conventional metrics.

The cultural context of Indonesia adds additional complexity to this relationship. In Javanese culture, the concept of “work” often encompasses broader social and community obligations beyond formal employment. Indonesian academics may view their scholarly activities as part of their social contribution, making strict work–life separation both artificial and culturally inappropriate (

Anafiah et al., 2020).

Furthermore, the hierarchical nature of Indonesian academic institutions may create conditions where academics who prioritize work–life balance are perceived as less committed or ambitious. This perception may result in reduced opportunities, resources, or institutional support, ultimately impacting their measured productivity. The collectivist orientation of Indonesian culture, which emphasizes group harmony and dedication to institutional goals, may further penalize those who prioritize personal balance over institutional demands.

Identity theory and work centrality: From an identity theory perspective, many Indonesian academics may derive their primary sense of self and social status from their professional achievements. For such individuals, work is not merely an economic necessity but a central component of their identity and self-worth (