Thinking with: Relationality and Lively Connections Within Urbanised Outdoor Community Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Relationality and the More-than-Human

Common worlding or the commoning of worlds requires a persistent commitment to reaffirm the inextricable entanglement of social and natural worlds—through experimenting with worldly kinds of pedagogical practice. This means pushing past the disciplinary framing of pedagogy as an a priori exclusively human activity and remaining open to what it might mean to learn collectively with the more-than-human world rather than about it, acknowledging more-than-human agency and paying attention to the mutual affects of human-nonhuman relations.

1.2. Shifting Teachers’ Thinking and Doing

1.3. Singapore and Thinking with Local Place

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

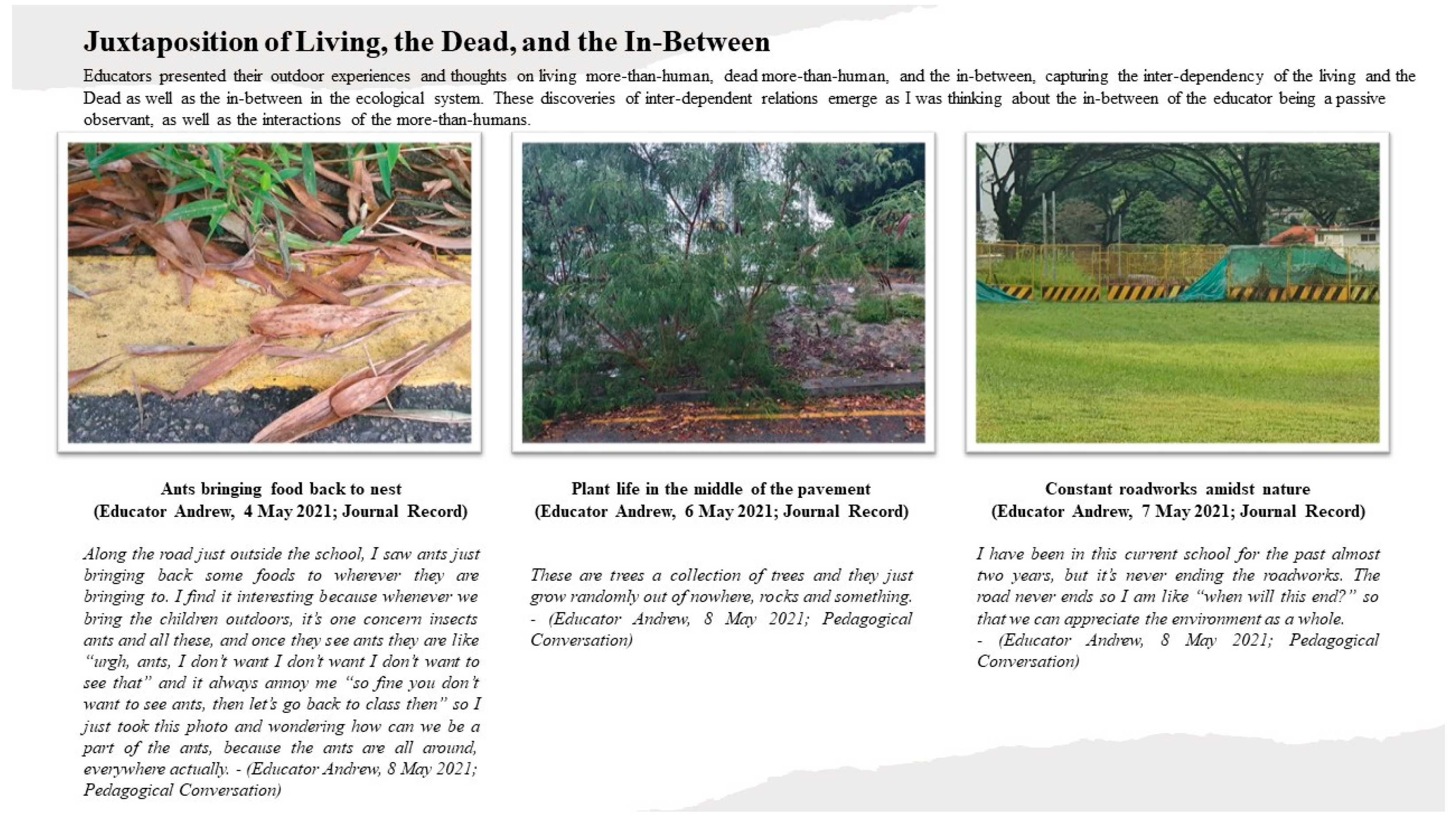

Juxtaposition of the Living, the Dead, and the In-Between

Educator Andrew: These photos were taken throughout the week as I made my way to work. The journey to and from usually takes about 15 to 20 min, i.e., from bus stop to school compound (workplace). Along the way, there were various interesting observations which have been captioned in the next few slides.

Educator Andrew: I took these photos on a daily basis, because it’s quite a long walk from the bus stop or the MRT (train station) to our school, and I feel that it’s quite an interesting thing to do because previously I used to just walk past without noticing anything. But now because I am given the task to observe and look around more and I start to notice a little bit more and find interesting things.

Educator Andrew: Sometimes they talk too much and I shut them down unfortunately. But that brings about the point where I said because I am not an expert in this subject matter, so I was shutting them down because I don’t know how to answer their questions, but in this instance, I am like I can google this, and these are actually xxx mushrooms and whatever plants then I can share the info with them. After I took this photo (Life growing atop a dead log), that was what I was thinking.

Educator Bridget: I don’t actually know whether they are able to conceptualise how living things feel, like just a simple action can dramatically affect. How do they know that if I do this, then it might die? Do they actually know what death is? I don’t know whether this is the best time to introduce this kind of thing. They are still quite young.

Educator Andrew: I have pets in class so I remember that the most recent one was the fish, they died one by one. The children understood that it died, it cannot move already. So their thoughts was ok what to do with this? They are wondering will it affect other fish in the tank, so they want to remove it so that the other fish can continue living. After that, they said we can bury it. Then when the last fish died, they were quite upset already, because they were “oh no, now we have no more fish in our class”. But then their immediate thing they think is “when can we get another one?” So I don’t know maybe to the children they take it for granted that things come and go, maybe these are animals, not friends or humans.

Educator Clara: The way adult or caregiver facilitate the way children take care of the pets will make a difference. The way caregiver if they just only feed, if the caregiver doesn’t really show how the pet is important or what it can do, then the children will not be able to see it as another member in the classroom, then they will not really treasure it that much as compared to if the caregiver really look after it and play with it more often. So I think the caregiver’s role also plays a part in putting importance on the pet.

Educator Patricia: Are children in the preschool age able to really process what death is? If so how do we as teachers help facilitate and guide their emotions whether it be consoling or helping them understand that their actions may lead to the death of the animal.

Educator Bridget: Even if the pets are gone, or the grandparents have left them, I don’t think they are able to understand they are not coming back anymore, I am also not sure how I can as an educator facilitate them to understand that they are not coming back anymore.

Educator Andrew: Even after so many years of teaching, I still cannot explain death to the children. Every time I come across something like this, I will try not to remind children of that. Even after so many years, I don’t know how to approach this topic of this is gone, it won’t come back. For animals, like I mentioned just now, the children were just like “oh we just get another one” to them it’s like maybe just the colours different on the fish. It’s like ok can buy a new one, get a new one. But if it’s for humans, for people, we can’t just say “oh, I love my grandmother, I can just get a new grandma” it’s not as simple as that, so it’s very difficult to explain to them.

Educator Clara: One of the experiences I had in my previous school, was when one of the pets died, the teacher gathered the children, at that time the children didn’t notice the animals died, and after a while the teacher guided the children to notice that the pets died in the container. And once the children noticed it, they get them to come up with a name for the pet, and went through the process of what should we do next, burying, then where should we bury, and what should we put. So they went through the whole process of digging the hole together, putting rock to mark that spot so that other people will not step on it or touch the area, and they put a signage for the pet also. Then in the following 2 weeks, they re-visited the place, just like how you visit someone who passed away so they just re-visited the spot where they buried and I think it was a nice closure to the children when they learnt that the pets are gone, then it’s just like respecting what happened. So it’s not an abrupt ending or a sudden loss.

Educator Bridget: I am interested to know how parents would react, like if we have a class pet that died and then the children tell the parents “I buried the pets and I visit him once in a while” are parents ok with that? or do we need to seek permission beforehand? or are parents like this is taboo, don’t want that.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aagaard, J. (2021). Troubling the troublemakers: Three challenges to post-qualitative inquiry. International Review of Qualitative Research, 15(3), 311–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, S., Semenec, P., & Diaz-Diaz, C. (2020). Interview with Sonja Arndt. In C. Diaz-Diaz, & P. Semenec (Eds.), Posthumanist and new materialist methodologies (pp. 3–11). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, K. (2012). Pedagogical narration: What’s it all about? The Early Childhood Educator, 27, 3–7. Available online: http://www.jbccs.org/uploads/1/8/6/0/18606224/pedagogical_narration.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28(3), 801–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barad, K. (2010). Quantum entanglements and hauntological relations of inheritance: Dis/continuities, spacetime enfoldings, and justice-to-come. Derrida Today, 3(2), 240–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastien-Valenca, M. (2020). Experimenting with multiple literacies in family literacy intervention programs: From rhizocurriculum, rhizo-teaching to language education. In F. Bangou, M. Waterhouse, & D. Fleming (Eds.), Deterritorializing language, teaching, learning, and research: Deleuzo-Guattarian perspectives on second language education (pp. 153–171). Brill Sense. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, A., Moreno-Núñez, A., Ng, S. C., & Bull, R. (2018). Preschool educators’ interactions with children about sustainable development: Planned and incidental conversations. International Journal of Early Childhood, 50(1), 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaise, M., Hamm, C., & Iorio, J. M. (2017). Modest witness(ing) and lively stories: Paying attention to matters of concern in early childhood. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 25(1), 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozalek, V., & Fullagar, S. (2022). Noticing. In K. Murris (Ed.), A glossary for doing postqualitative, new materialist and critical posthumanist research across disciplines (pp. 94–95). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S. P., McKesson, L. D., Robinson, J., & Jackson, A. Y. (2021). Possibles and post qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 27(2), 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. (2004). Precarious life: The powers of mourning and violence. Verso. [Google Scholar]

- Castle, K. (2020). Early childhood teacher research: From questions to results (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cele, S. (2019). Trees. In P. Rautio, & E. Stenvall (Eds.), Social, material and political constructs of arctic childhoods: An everyday life perspective (pp. 1–17). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Common Worlds Research Collective. (2020). Learning to become with the world: Education for future survival. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Education Sector. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374032 (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Early Childhood Development Agency. (2020). Guide to setting up an early childhood development centre (ECDC). Available online: https://www.ecda.gov.sg/operators/setting-up-a-preschool/setting-up-an-ecdc (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Ebbeck, M., Yim, H. Y. B., & Warrier, S. (2019). Early childhood teachers’ views and teaching practices in outdoor play with young children in Singapore. Early Childhood Education Journal, 47(3), 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawcett, L. (2002). Children’s wild animal stories: Questioning inter-species bonds. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 7(2), 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, G., Hall, E., & Berglund, K. (2001). The power of ordinary moments. Child Care Information Exchange. Available online: https://www.childcareexchange.com/catalog/product/the-power-of-ordinary-moments/5014152/ (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Hamm, C., & Iorio, J. M. (2020). Place in early childhood teacher education. In M. A. Peters (Ed.), Encyclopedia of teacher education (pp. 1–5). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, C., Iorio, J. M., Cooper, J., Smith, K., Crowcroft, P., Molloy Murphy, A., Parnell, W., & Yelland, N. (2023). Learning with place as a catalyst for action. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D. (2008). When species meet. University of Minnesota press. [Google Scholar]

- Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the chthulucene. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heydon, R. (2009). We are here for just a brief time: Death, dying, and constructions of children in intergenerational learning programs. In L. Iannacci, & P. Whitty (Eds.), Early childhood curricula: Reconceptualist perspectives (pp. 217–241). Detselig. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins, B. D. (Ed.). (2019). Common worlding research: An introduction. In Feminist research for 21st-century childhoods: Common worlds methods (pp. 1–22). Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, M., Elliott, S., Mitsuhashi, M., & Kido, H. (2019). Nature-based early childhood activities as environmental education?: A review of Japanese and Australian perspectives. Japanese Journal of Environmental Education, 28(4), 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio, J. M., Hamm, C., Parnell, W., & Quintero, E. (2017). Place, matters of concern, and pedagogy: Making impactful connections with our planet. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 38(2), 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A. Y., & Mazzei, L. A. (2012). Thinking with theory in qualitative research: Viewing data across multiple perspectives. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lenz Taguchi, H. (2010). Going beyond the theory/practice divide in early childhood education: Introducing an intra-active pedagogy. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, K. (2018). Children in the anthropocene: Rethinking sustainability and child friendliness in cities. Palgrave Macmillan Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D. L. (1988). Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, P. (2019). Alternative narratives in early childhood: An introduction for students and practitioners (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, A. M. (2021). The grass is moving but there is no wind: Common worlding with elf/child relations. Journal of Curriculum and Pedagogy, 18(2), 134–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murris, K. (2021). The ‘Missing Peoples’ of critical posthumanism and new materialism. In K. Murris (Ed.), Navigating the postqualitative, new materialist and critical posthumanist terrain across disciplines (pp. 62–84). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, N. (2020). Rats, death, and anthropocene relations in urban canadian childhoods. In A. Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, K. Malone, & E. Barratt Hacking (Eds.), Research handbook on childhoodnature (pp. 637–659). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S. C., & Bull, R. (2018). Facilitating social emotional learning in kindergarten classrooms: Situational factors and teachers’ strategies. International Journal of Early Childhood, 50(3), 335–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S. C., & Sun, H. (2022). Promoting social emotional learning through shared book reading: Examining teacher’s strategies and children’s responses in kindergarten classrooms. Early Education and Development, 33(8), 1326–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nxumalo, F. (2015). Forest stories: Restorying encounters with “natural” places in early childhood education. In V. Pacini-Ketchabaw, & A. Taylor (Eds.), Unsettling the colonial places and spaces of early childhood education (pp. 21–42). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Osberg, D., & Biesta, G. (2010). The end/s of education: Complexity and the conundrum of the inclusive educational curriculum. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 14(6), 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Out and About. (2019). Out and about manifesto. Available online: https://www.goingoutandabout.net/manifesto (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Pacini-Ketchabaw, V., Taylor, A., & Blaise, M. (2016). Decentring the human in multispecies ethnographies. In C. A. Taylor, & C. Hughes (Eds.), Posthuman research practices in education (pp. 149–167). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L., & St. Pierre, E. A. (2017). Writing: A method of inquiry. In N. Denzin, & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (5th ed., pp. 1410–1444). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney, T. (2019). Sticking: Children and the lively matter of sticks. In B. D. Hodgins (Ed.), Feminist research for 21st century childhoods: Common worlds methods (pp. 43–52). Bloomsbury Collections. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D. B. (2013). Death and grief in a world of kin. In G. Harvey (Ed.), The handbook of contemporary animism (pp. 137–147). Acumen Publishing. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/handbook-of-contemporary-animism/death-and-grief-in-a-world-of-kin/F67F7B7A2B9C225A3D5A24446BD3CE4E (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Rose, D. B., Van Dooren, T., & Chrulew, M. (Eds.). (2017). Extinction studies: Stories of time, death, and generations. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, J. (2016). I remember everything: Children, companion animals, and a relational pedagogy of remembrance. In M. DeMello (Ed.), Mourning animals: Rituals and practices surrounding animal death (pp. 81–90). Michigan State University Press. Available online: https://library.deakin.edu.au/record=b3515237~S9 (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Russell, J. (2017). ‘Everything has to die one day: ’Children’s explorations of the meanings of death in human-animal-nature relationships. Environmental Education Research, 23(1), 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte, C. M. (2019). The untimely death of a bird: A posthuman tale. In C. R. Kuby, K. Spector, & J. J. Thiel (Eds.), Posthumanism and literacy education: Knowing/becoming/doing literacies (pp. 71–81). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, M., & Green, M. (2015). Children, place and sustainability. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- St. Pierre, E. A. (2011). Post qualitative research: The critique and the coming after. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative inquiry (4th ed., pp. 611–635). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- St. Pierre, E. A. (2019). Post qualitative inquiry in an ontology of immanence. Qualitative Inquiry, 25(1), 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachan, A. L., Lim, E., Yip, H. Y., & Lum, G. (2017). Early childhood educator perspectives on the first year of implementing an outdoor learning environment in Singapore. Learning: Research and Practice, 3(2), 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X. R., & Yang, W. (2022). Pedagogical documentation as a curriculum tool: Making children’s outdoor learning visible in a childcare centre in Singapore. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 30(2), 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A. (2013). Reconfiguring the natures of childhood. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, A. (2017). Beyond stewardship: Common world pedagogies for the anthropocene. Environmental Education Research, 23(10), 1448–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A., & Pacini-Ketchabaw, V. (2015). Learning with children, ants, and worms in the anthropocene: Towards a common world pedagogy of multispecies vulnerability. Pedagogy, Culture, Society, 23(4), 507–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronto, J. C. (2013). Caring democracy markets, equality, and justice. New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsing, A. (2012). Unruly edges: Mushrooms as companion species. Environmental Humanities, 1(1), 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsing, A. (2015). The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer, J. B. (2017). Posthumanism as research methodology: Inquiry in the Anthropocene. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(9), 832–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldemariam, K. (2017). Challenging and expanding the notion of sustainability within early childhood education: Perspectives from post-humanism and/or new materialism. In O. Franck, & C. Osbeck (Eds.), Ethical literacies and education for sustainable development: Young people, subjectivity and democratic participation (pp. 105–126). Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ng, S.C.; Iorio, J.M.; Yelland, N. Thinking with: Relationality and Lively Connections Within Urbanised Outdoor Community Environments. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091109

Ng SC, Iorio JM, Yelland N. Thinking with: Relationality and Lively Connections Within Urbanised Outdoor Community Environments. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091109

Chicago/Turabian StyleNg, Siew Chin, Jeanne Marie Iorio, and Nicola Yelland. 2025. "Thinking with: Relationality and Lively Connections Within Urbanised Outdoor Community Environments" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091109

APA StyleNg, S. C., Iorio, J. M., & Yelland, N. (2025). Thinking with: Relationality and Lively Connections Within Urbanised Outdoor Community Environments. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1109. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091109