Teacher-to-Student Victimization: The Role of Teachers’ Victimization and School Social and Organizational Climates

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Teacher-to-Student Victimization

1.2. Teachers’ Victimization

1.3. School Social Climate

1.4. School Organizational Climate

1.4.1. Interpersonal Conflict at Work

1.4.2. Job Socialization

1.4.3. Trust in the Principal

1.5. Study Context

2. Methods

2.1. Study Procedure and Sample

2.2. Measurements

2.2.1. Dependent Variable

2.2.2. Independent Variables

2.3. Statistical Analysis

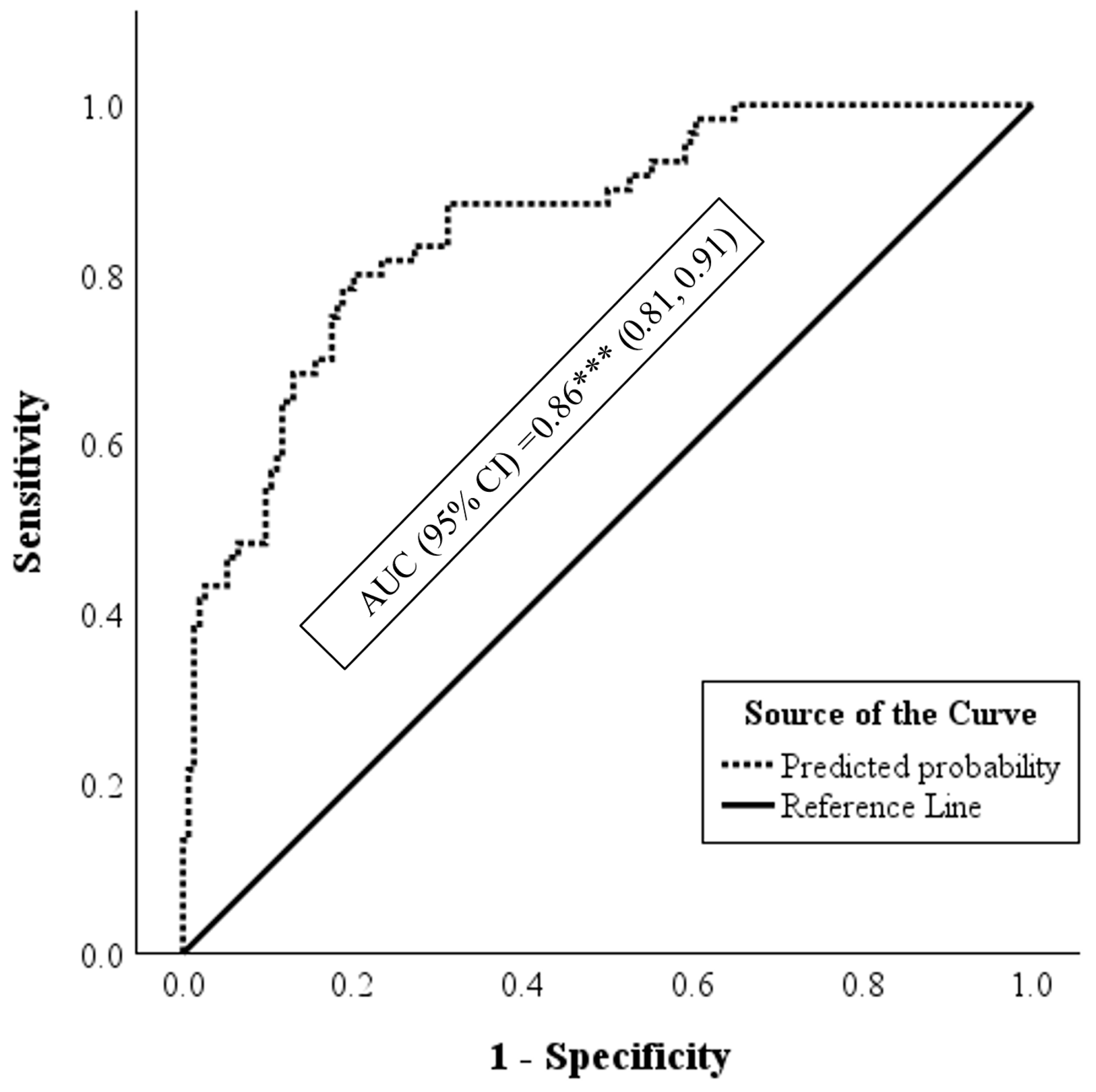

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Multivariate Prediction of Teacher-to-Student Victimization

4.2. Study Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| School Social Climate | Interpersonal Conflict | Trust in Principal | Job Socialization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. School social climate | -- | −0.66 ** | 0.57 ** | 0.56 ** |

| 2. Interpersonal conflict | -- | −0.60 ** | −0.64 ** | |

| 3. Trust in principal | -- | 0.55 ** | ||

| 4. Job socialization | -- |

References

- Abu-Asba, H., Jayusi, W., & Sabar-Ben Yehoshua, N. (2011). זהותם של בני נוער פלסטינים אזרחי ישראל, מידת הזדהותם עם המדינה, ועם התרבות היהודית וההשתמעויות למערכת החינוך [The identity of Palestinian youngsters who are Israeli citizens: The extent of their identification with the state and with Jewish culture, and the implications for the education system]. Dapim: Journal for Studies and Research in Education, 52, 11–45. [Google Scholar]

- Afifi, T. O., MacMillan, H. L., Taillieu, T., Cheung, K., Turner, S., Tonmyr, L., & Hovdestad, W. (2015). Relationship between child abuse exposure and reported contact with child protection organizations: Results from the Canadian Community Health Survey. Child Abuse & Neglect, 46, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Haj, M., & Rosenfeld, H. (2020). Arab local government in Israel. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- American Educational Research Association. (2013). Prevention of bullying in schools, colleges, and universities: Research report and recommendations. American Educational Research Association. [Google Scholar]

- Arar, K. (2012). Israeli education policy since 1948 and the state of Arab education in Israel. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 4(1), 113–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arënliu, A., Benbenishty, R., Kelmendi, K., Duraku, Z. H., Konjufca, J., & Astor, R. A. (2022). Prevalence and predictors of staff victimization of students in Kosovo. School Psychology International, 43(3), 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astor, R. A., & Benbenishty, R. (2019). Bullying, school violence, and climate in evolving contexts: Culture, organization, and time. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Astor, R. A., Benbenishty, R., Capp, G. P., Watson, K. R., Wu, C., McMahon, S. D., Worrell, F. C., Reddy, L. A., Martinez, A., Espelage, D. L., & Anderman, E. M. (2024). How school policies, strategies, and relational factors contribute to teacher victimization and school safety. Journal of Community Psychology, 52(1), 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astor, R. A., Benbenishty, R., & Estrada, J. N. (2009). School violence and theoretically atypical schools: The principal’s centrality in orchestrating safe schools. American Educational Research Journal, 46(2), 423–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astor, R. A., Noguera, P., Fergus, E., Gadsden, V., & Benbenishty, R. (2021). A call for the conceptual integration of opportunity structures within school safety research. School Psychology Review, 50(2–3), 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenes-Ribera, L., Angelo Fabris, M., Martinez, A., McMahon, S. D., & Longobardi, C. (2022). Prevalence of parental violence toward teachers: A meta-analysis. Violence and Victims, 37(3), 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Henningham, H., Meeks-Gardner, J., Chang, S., & Walker, S. (2009). Experiences of violence and deficits in academic achievement among urban primary school children in Jamaica. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, G. G., Yang, C., Pell, M., & Gaskins, C. (2014). Validation of a brief measure of teachers’ perceptions of school climate: Relations to student achievement and suspensions. Learning Environments Research, 17, 339–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbenishty, R., & Astor, R. A. (2005). School violence in context: Culture, neighborhood, family, school, and gender. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., & Benbenishty, A. (2024). Listening to the voices of the school community as part of the welcoming, empowerment, and monitoring approach (WEMA) to improve school outcomes. In J. S. Hong, H. C. Chan, A. L. C. Fung, & J. Lee (Eds.), Handbook of school violence, bullying and safety (pp. 461–480). Edward Elgar. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., López, V., Bilbao, M., & Ascorra, P. (2019). Victimization of teachers by students in Israel and in Chile and its relations with teachers’ victimization of students. Aggressive Behavior, 45(2), 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbenishty, R., Daru, E. R., & Astor, R. A. (2022). An exploratory study of the prevalence and correlates of student maltreatment by teachers in Cameroon. International Journal of Social Welfare, 31, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J. K., & Cornell, D. (2016). Authoritative school climate, aggression toward teachers, and teacher distress in middle school. School Psychology Quarterly, 31(1), 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkowitz, R., Bar-on, N., Tzafrir, S., & Enosh, G. (2022). Teachers’ safety and workplace victimization: A socioecological analysis of teachers’ perspective. Journal of School Violence, 21(4), 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, R., & Ben-Artzi, E. (2024). The contribution of school climate, socioeconomic status, ethnocultural affiliation, and school level to language arts scores: A multilevel moderated mediation model. Journal of School Psychology, 104, 101281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounds, C., & Jenkins, L. N. (2018). Teacher-directed violence and stress: The role of school setting. Contemporary School Psychology, 22, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendgen, M., Wanner, B., Vitaro, F., Bukowski, W. M., & Tremblay, R. E. (2007). Verbal abuse by the teacher during childhood and academic, behavioral, and emotional adjustment in young adulthood. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruk-Lee, V., & Spector, P. E. (2006). The social stressors-counterproductive work behaviors link: Are conflicts with supervisors and coworkers the same? Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(2), 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryk, A., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.-K., & Wei, H. S. (2011). Student victimization by teachers in Taiwan: Prevalence and associations. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(5), 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-K., Wu, C., & Wei, H.-S. (2020). Personal, family, school, and community factors associated with student victimization by teachers in Taiwanese junior high schools: A multi-informant and multilevel analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 99, 104246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civitillo, S., Göbel, K., Preusche, Z., & Jugert, P. (2021). Disentangling the effects of perceived personal and group ethnic discrimination among secondary school students: The protective role of teacher–student relationship quality and school climate. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2021(177), 77–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., McCabe, E. M., Michelli, N. M., & Pickeral, T. (2009). School climate: Research, policy, practice, and teacher education. Teachers College Record, 111(1), 180–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L. M., Schafer, J. L., & Kam, C.-M. (2001). A comparison of inclusive and restrictive strategies in modern missing data procedures. Psychological Methods, 6(4), 330–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, W. J. (1980). Efficient analysis of experimental observations. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology, 20, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enosh, G., Tzafrir, S. S., & Stolovy, T. (2015). The development of client violence questionnaire (CVQ). Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 9(3), 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D., Anderman, E. M., Brown, V. E., Jones, A., Lane, K. L., McMahon, S. D., Reddy, L. A., & Reynolds, C. R. (2013). Understanding and preventing violence directed against teachers: Recommendations for a national research, practice, and policy agenda. American Psychologist, 68(2), 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evertson, C. M., & Smithey, M. W. (2000). Mentoring effects on protégés’ classroom practice: An experimental field study. Journal of Educational Research, 93(5), 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluke, J. D., Tonmyr, L., Gray, J., Rodrigues, L. B., Bolter, F., Cash, S., Jud, A., Meinck, F., Casas Muñoz, A., O’Donnell, M., Pilkington, R., & Weaver, L. (2021). Child maltreatment data: A summary of progress, prospects and challenges. Child Abuse & Neglect, 119, 104650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, J., Gong, T., & Attoh, P. (2015). The impact of principal as authentic leader on teacher trust in the K-12 educational context. Journal of Leadership Studies, 8(4), 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galand, B., Lecocq, C., & Philippot, P. (2007). School violence and teacher professional disengagement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 465–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, D. G., Huang, G. H., Pierce, J. L., Niu, X., & Lee, C. (2022). Not just for newcomers: Organizational socialization, employee adjustment and experience, and growth in organization-based self-esteem. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 33(3), 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gershoff, E. T. (2017). School corporal punishment in global perspective: Prevalence, outcomes, and efforts at intervention. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 22(Suppl. 1), 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A., & Ripski, M. B. (2008). Adolescent trust in teachers: Implications for behavior in the high school classroom. School Psychology Review, 37(3), 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greif-Green, J., Furlong, M. J., Astor, R. A., Benbenishty, R., & Espinoza, E. (2011). Assessing school victimization in the United States, Guatemala, and Israel: Cross-cultural psychometric analysis of the School Victimization Scale. Victims and Offenders, 6(3), 290–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneş, Ç., & Uysal, H. H. (2019). The relationship between teacher burnout and organizational socialization among English language teachers. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 15(1), 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, J. A. (2005). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. In Encyclopedia of biostatistics. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Hecker, T., Hermenau, K., Isele, D., & Elbert, T. (2014). Corporal punishment and children’s externalizing problems: A cross-sectional study of Tanzanian primary school aged children. Child Abuse and Neglect, 38(5), 884–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heekes, S. L., Kruger, C. B., Lester, S. N., & Ward, C. L. (2022). A systematic review of corporal punishment in schools: Global prevalence and correlates. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(1), 52–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hox, J., Moerbeek, M., & Van de Schoot, R. (2017). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hoy, W. K., & Tarter, C. J. (2004). Organizational justice in schools: No justice without trust. International Journal of Educational Management, 18(4), 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F. L., Eddy, C. L., & Camp, E. (2020). The role of the perceptions of school climate and teacher victimization by students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(23–24), 5526–5551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingersoll, R. M., & Strong, M. (2011). The impact of induction and mentoring programs for beginning teachers: A critical review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 201–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israel Archives. (2017). 1948–1953—בסוף הכול מתחיל בחינוך- הזרמים בחינוך ומה שביניהם [In the end, everything starts with education: The educational streams and what’s in between, 1948–1953]. Available online: https://www.archives.gov.il (accessed on 19 August 2025). (In Hebrew).

- Jennings, W. G., Piquero, A. R., & Reingle, J. M. (2012). On the overlap between victimization and offending: A review of the literature. Aggression & Violent Behavior, 17(1), 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. R. (1986). Socialization tactics, self-efficacy, and newcomers’ adjustments to organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 29(2), 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassir, N., Pinnes, R., & Flam, N. (2024). Standard of living, poverty and social gaps report. National Insurance Institute of Israel. Available online: https://www.btl.gov.il/Publications/oni_report/Documents/dohaoni2023.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Kim, J., & Ko, Y. (2022). Perceived discrimination and workplace violence among school health teachers: Relationship with school organizational climate. Research in Community and Public Health Nursing, 33(4), 432–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kızıltepe, R., Irmak, T. Y., Eslek, D., & Hecker, T. (2020). Prevalence of violence by teachers and its association to students’ emotional and behavioral problems and school performance: Findings from secondary school students and teachers in Turkey. Child Abuse & Neglect, 107, 104559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longobardi, C., Badenes-Ribera, L., Fabris, M. A., Martinez, A., & McMahon, S. D. (2019). Prevalence of student violence against teachers: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Violence, 9(6), 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, V., Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., Ascorra, P., & González, L. (2020). Teachers victimizing students: Contributions of student-to-teacher victimization, peer victimization, school safety, and school climate in Chile. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 90(4), 432–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, V., Torres-Vallejos, J., Villalobos-Parada, B., Gilreath, T. D., Ascorra, P., Bilbao, M., Morales, M., & Carrasco, C. (2017). School and community factors involved in Chilean students’ perception of school safety. Psychology in the Schools, 54(9), 991–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, A. (2021). Effect of corporal punishment on young children’s educational outcomes. Education Economics, 29(4), 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, A., McMahon, S. D., Espelage, D., Anderman, E. M., Reddy, L. A., & Sanchez, B. (2016). Teachers’ experiences with multiple victimization: Identifying demographic, cognitive, and contextual correlates. Journal of School Violence, 15(4), 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masath, F. B., Hinze, L., Nkuba, M., & Hecker, T. (2022). Factors contributing to violent discipline in the classroom: Findings from a representative sample of primary school teachers in Tanzania. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(17–18), NP15455–NP15478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, S. D., Anderman, E. M., Astor, R. A., Espelage, D. L., Martinez, A., Reddy, L. A., & Worrell, F. C. (2022). Violence against educators and school personnel: Crisis during COVID: Technical report. American Psychological Association. Available online: https://www.apa.org/education-career/k12/violence-educators-technical-report.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- McMahon, S. D., Bare, K. M., Cafaro, C. L., Zinter, K. E., Garcia-Murillo, Y., Lynch, G., McMahon, K. M., Espelage, D. L., Reddy, L. A., Anderman, E. M., & Subotnik, R. (2023). Understanding parent aggression directed against teachers: A school climate framework. Learning Environments Research, 26(3), 915–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S. D., Reaves, S., McConnell, E., Peist, E., & Ruiz, L. (2017). The ecology of teachers’ experiences with violence and lack of administrative support. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60(3–4), 502–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A. K., & Mishra, K. E. (1994). The role of mutual trust in effective downsizing strategies. Human Resource Management, 33(2), 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Authority of Measurement and Evaluation in Education. (2022). ניטור רמת האלימות והתנהגויות בסיכון בבתי ספר לפי דיווחי התלמידים תשס”ט-תשפ”ב [Monitoring the level of violence and risk behaviors in schools based on student reports]. Available online: https://meyda.education.gov.il/files/Rama/violence-nitur-2022.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- National Authority of Measurement and Evaluation in Education. (2024). סקר מורים תשפ”ג [Teachers’ survey 2022–2023]. Available online: https://meyda.education.gov.il/files/Rama/Surveys23_teachers.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2025).

- National School Climate Council. (2007). The school climate challenge: Narrowing the gap between school climate research and school climate policy, practice guidelines and teacher education policy. Available online: https://schoolclimate.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/school-climate-challenge-web.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Oliver, R. M., Wehby, J. H., & Reschly, D. J. (2011). Teacher classroom management practices: Effects on disruptive or aggressive student behavior. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A. A., Gottfredson, D. C., & Gottfredson, G. D. (2003). Schools as communities: The relationships among communal school organization, student bonding, and school disorder. Criminology, 41(3), 749–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peist, E., McMahon, S. D., Davis-Wright, J. O., & Keys, C. B. (2024). Understanding teacher-directed violence and related turnover through a school climate framework. Psychology in the Schools, 61(1), 220–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A. H., Martinez, A., Reddy, L. A., McMahon, S. D., Anderman, E. M., Astor, R. A., Espelage, D. L., & Worrell, F. C. (2024). Addressing violence against educators: What do teachers say works? School Psychology, 39(5), 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, L. A., Espelage, D. L., Anderman, E. M., Kanrich, J. B., & McMahon, S. D. (2018). Addressing violence against educators through measurement and research. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 42, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, L. A., Perry, A. H., Martinez, A., McMahon, S. D., Bare, K., Swenski, T., Dudek, C. M., Anderman, E. M., Astor, R. A., Espelage, D. L., & Worrell, F. C. (2024). Student violence against paraprofessionals in schools: A social-ecological analysis of safety and well-being. Behavioral Sciences, 14(12), 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, P. E., & Jex, S. M. (1998). Development of four self-report measures of job stressors and strain: Interpersonal conflict at work scale, organizational constraints scale, quantitative workload inventory, and physical symptoms inventory. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3(4), 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonmyr, L., Mathews, B., Shields, M. E., Hovdestad, W. E., & Afifi, T. O. (2018). Does mandatory reporting legislation increase contact with child protection?—A legal doctrinal review and an analytical examination. BMC Public Health, 18, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaatut, A., & Haj-Yahia, M. M. (2016). Beliefs about wife beating among Palestinian women from Israel: The effect of their endorsement of patriarchal ideology. Feminism & Psychology, 26(4), 405–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Total | Teacher-to-Student Victimization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||||

| (N = 214) | (n = 154) | (n = 60) | |||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | χ2 | |

| Gender | 2.63 | ||||||

| Male | 64 | 29.9 | 41 | 64.1 | 23 | 35.9 | |

| Female | 148 | 69.2 | 111 | 75.0 | 37 | 25.0 | |

| Age | 0.04 | ||||||

| 18–40 | 79 | 36.9 | 56 | 70.9 | 23 | 29.1 | |

| 41+ | 133 | 62.1 | 96 | 72.2 | 37 | 27.8 | |

| Ethnocultural affiliation | 18.81 *** | ||||||

| Hebrew speaking | 147 | 68.7 | 119 | 81.0 | 28 | 19.0 | |

| Arabic speaking | 67 | 31.3 | 35 | 52.2 | 32 | 47.8 | |

| Professional role | 4.27 | ||||||

| Teacher | 86 | 40.2 | 60 | 69.8 | 26 | 30.2 | |

| Homeroom teacher | 66 | 30.8 | 52 | 78.8 | 14 | 21.2 | |

| Grade coordinator | 24 | 11.2 | 18 | 75.0 | 6 | 25.0 | |

| Other | 35 | 16.4 | 21 | 60.0 | 14 | 40.0 | |

| Years at school | 6.86 ** | ||||||

| 1–10 | 111 | 51.9 | 87 | 78.4 | 24 | 21.6 | |

| 11+ | 91 | 42.5 | 56 | 61.5 | 35 | 38.5 | |

| Variable | Teacher-to-Student Victimization | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||||

| (n = 154) | (n = 60) | |||||

| Categorical | n | % | n | % | χ2 | |

| Teacher victimization | 2.70 | |||||

| No | 81 | 77.1 | 24 | 22.9 | ||

| Yes | 71 | 67.0 | 35 | 33.0 | ||

| Continuous | M | SD | M | SD | t | d |

| Social climate | 4.22 | 0.39 | 3.73 | 0.43 | 8.06 *** | 1.23 |

| Interpersonal conflict at work | 1.42 | 0.35 | 1.90 | 0.60 | −5.84 *** | −1.11 |

| Trust in the principal | 52.20 | 8.97 | 44.23 | 11.61 | 4.79 *** | 0.81 |

| Job socialization | 3.32 | 0.86 | 2.64 | 0.88 | 5.15 *** | 0.78 |

| Independent Variable | Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | OR | AME | b (SE) | OR | AME | b | OR | AME | |

| Ethnocultural affiliation (1 = Arabic speaking) | 1.36 *** (0.32) | 3.89 | 0.287 | 0.72 * (0.38) | −2.06 | 0.117 | 0.83 * (0.40) | 2.28 | 0.129 |

| Social climate | −2.52 *** (0.47) | 0.08 | −0.372 | −1.56 ** (0.60) | 0.21 | −0.219 | |||

| Interpersonal conflict at work | 1.31 * (0.58) | 3.71 | 0.184 | ||||||

| Trust in principal | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.99 | −0.001 | ||||||

| Job socialization | −0.03 (0.27) | 0.97 | −0.003 | ||||||

| Intercept | −1.45 *** (0.21) | 8.85 *** (1.92) | 3.39 (2.85) | 29.74 | |||||

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.116 | 0.335 | 0.379 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Berkowitz, R. Teacher-to-Student Victimization: The Role of Teachers’ Victimization and School Social and Organizational Climates. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091090

Berkowitz R. Teacher-to-Student Victimization: The Role of Teachers’ Victimization and School Social and Organizational Climates. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(9):1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091090

Chicago/Turabian StyleBerkowitz, Ruth. 2025. "Teacher-to-Student Victimization: The Role of Teachers’ Victimization and School Social and Organizational Climates" Education Sciences 15, no. 9: 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091090

APA StyleBerkowitz, R. (2025). Teacher-to-Student Victimization: The Role of Teachers’ Victimization and School Social and Organizational Climates. Education Sciences, 15(9), 1090. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15091090