Abstract

For decades, the U.S. college admissions process has utilized standardized exams as critical indicators of college readiness. With the onset of the COVID pandemic, the majority of 4-year universities implemented the Test-Optional policy to improve college access and enrollment. The Test-Optional policy allows prospective high school students to apply to institutions that have implemented this policy without a SAT or ACT score. This study examined the use of the Test-Optional policy and its relationship with early college success. Forward multiple regression examined which variables of High School GPA, Students of Color, First-Generation Status, Test-Optional, Pell Eligible, and Pre-College Credits best predict undergraduate first-year GPA. The results generated a five-variable model that accounted for 31% of the variability in first-year college GPA. High School GPA was the strongest predictor, while Test-Optional was not entered into the model. Binary logistic regression examined predictors of first-year college completion. Our results revealed the model including High School GPA, which tripled the odds of first-year completion. Again, Test-Optional was not included in the model. Although Students of Color and Pell Eligibility utilized Test-Optional significantly more than their peers, Test-Optional was not a significant predictor of first-year College GPA or first-year completion.

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of the Study

This correlational study examined various U.S. student characteristics (Students of Color Status, First-Generation Status, and Pell Eligibility) and academic factors (Test-Optional, High School GPA, and Pre-College Credits) to predict early college success as defined by first-year grade point average (GPA) and first-year completion at the end of the undergraduate first year. The study specifically focused on how the use of the Test-Optional in conjunction with other variables predicts early college success. The census sample included 3603 first-year undergraduate students at a Midwest, Ohio institution using the Test-Optional policy and those who applied with their test scores. Tinto’s (1993) Student Integration Theory framed the study as we examined pre-entry attributes (i.e., Students of Color Status, First-Generation Status, and Pell Eligibility) and academic goals and commitments (i.e., Test-Optional, High School GPA, and Pre-College Credits) predicting first-year college outcomes, cumulative grade point average (GPA), and first-year completion. The secondary dataset was obtained from a midwestern public university in the United States through its Office of Institutional Research. The studied institution is classified as a high research spending and doctorate production (R2) institution and offers about 200 majors and programs for undergraduate students (Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research, n.d.).

1.2. Literature Review

Foundationally, how U.S. college admissions review applicants has evolved; each institution examines a variety of credentials when admitting students. Many educators have questioned the college admission processes and whether those reviews are equitable across student demographics. Bowman and Bastedo (2018) assert that “Admissions office practices can be highly distinctive, with variation in practices that are disconnected from evidence on effectiveness, such as the connection between admissions criteria and student success, or equity considerations” (p. 432). The authors continue to explain that students’ needs also transform as students change over time. Unfortunately, many universities tend to select candidates with similar self-presentation, experiences, and personal identity to that of the institution (Bowman & Bastedo, 2018). For example, if an institution’s priority is to admit high-achieving students, admission stakeholders will examine students’ applications for high GPAs and course grades, along with letters of recommendation and school involvement. Examining students’ college applications with one lens, instead of examining the whole student, may put minority populations at a disadvantage. Therefore, minority populations may be hindered by an application process that does not fully consider the overall application because the admissions stakeholders may only review their academic history.

A primary measure of high school academic achievement and college readiness has been standardized exams, which have long since been a critical component for college applications (Camara & Mattern, 2022). “Before 1900, each college or university in the United States that required an entrance exam developed and used its own, institution-specific battery of questions and essays to assess the preparation of applicants” (Syverson, 2007). Entrance exams, or most standardized tests, assess mastery of high school content and curriculum (Cai, 2020). For the past fifty years, the most common standardized tests for college admissions have been the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT) and American College Testing (ACT) within the College Board. The College Board is a non-profit organization that funds the SAT and ACT and creates paths for students wanting to pursue college. The SAT assesses “higher order reasoning skills,” unrelated to the high school curriculum. In contrast, the ACT assesses the mastery of the curriculum, which is closely related to high school content areas.

For decades, the college admissions process has utilized the ACT and SAT standardized exams as critical indicators for school stakeholders to assess whether students are college-ready (Camara & Mattern, 2022). Standardized exams help establish a prior knowledge assessment of what students know and do not know. The ACT and SATs “have taken on a mystical importance in modern American society, being used as a yardstick for assessing the quality of high schools and colleges and having a major impact on everything from a student’s self-image to the price of homes in a particular neighborhood” (Syverson, 2007). In addition, research on the ACT and SAT continues to indicate cultural and racial bias, leaving Students of Color and/or of low-income at a clear disadvantage when applying for college (Allensworth & Clark, 2020). In other words, the design and content of the SAT and ACT may favor certain racial groups. Cultural bias in the standardized tests may emerge from the language and scenarios that are more familiar to White students than those from different socioeconomic backgrounds. In addition, students who do not have access to test preparation resources, such as tutoring and test preparation courses, are at a disadvantage (Allensworth & Clark, 2020).

College admissions and test makers have sought processes, measures, and criteria that give all students an equal chance to be accepted and thrive in a college environment (Camara & Mattern, 2022). However, equal opportunity in education has yet to be achieved (Allensworth & Clark, 2020). Students’ need to be adequately prepared for college has disproportionately impacted Students of Color and First-Generation Students (Harris, 2020). Research has revealed that “African American students are less likely than White students to have access to college-ready courses; 57% of Black students have access to a full range of math and science courses necessary for college readiness, compared to 81% of Asian American students and 71% of White students” (Cestau et al., 2023, p. 252). Furthermore, “nearly 1 in 3 college students (30%) are first-generation students of color” (Schuyler et al., 2021, pp. 12–14). Moreover, Black and Latinx identities are the most represented as First-Generation Students because of intersectionality, which “asserts that individuals experience life events and are perceived by others through interaction of the different identities they hold” (p. 12). First-Generation Students are the first to attend college in their families and typically lack an understanding of college readiness resources (Davis, 2010).

The Test-Optional policy in college admissions evolved during the COVID-19 pandemic to improve college access and enrollment. The Test-Optional policy allows prospective high school students to apply to institutions that have implemented this policy without a SAT or ACT score. The pandemic created a world in lockdown, with schools, businesses, and restaurants all closed. People were restricted to their homes and required to wear face masks when leaving. The implementation of online instruction across all U.S. classrooms began in March 2020 and continued for many students through 2021. This drastic change in the learning environment affected the quality of teaching and learning, leaving many high school students and graduates ill-prepared for college (Hosler et al., 2019). Most high school juniors and seniors were unable to take the ACT or SAT due to canceled test dates. As a result, more than two-thirds of four-year colleges lifted the ACT/SAT requirement (FairTest, 2013). The Test-Optional policy has become widely recognized and implemented since 2020, affecting the college admission review process (Bennett, 2022). Although the Test-Optional policy was implemented in response to the pandemic, it was implemented to increase higher education access, access that may be limited due to the inability to take the ACT/SAT, poor performance on the ACT/SAT, and being a Student of Color and/or low-income.

Although early research has shown that the Test-Optional policy has increased admissions access to Students of Color who initially would only apply to some institutions (Paterson, 2022), the full impact of this policy is still to be determined. Limited research has explored the effects of using the no-test option on college success among Students of Color and with First-Generation Status. In addition, four-year institutions are contemplating the continuation of the Test-Optional policy since COVID restrictions have lifted and a three-year pilot of the policy has been implemented (Lovell & Mallinson, 2023). The present research provides vital information to admissions policymakers in determining the policy’s future. Continuation of the Test-Optional policy may benefit prospective college students, predominantly Students of Color and First-Generation Students, as it eliminates several barriers in the college admissions process.

1.3. Theoretical Framework

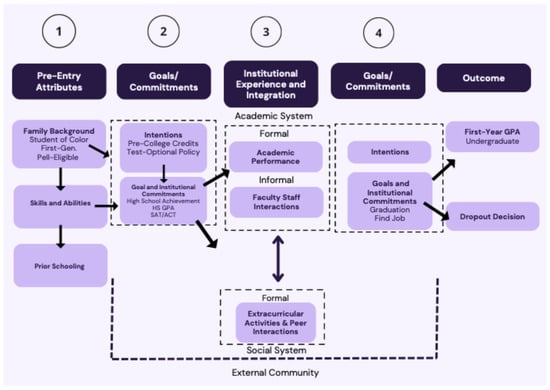

Vincent Tinto’s (1993) Student Integration Theory provides the framework for examining student characteristics and academic factors that predict early college success. Tinto’s perspective examines students’ cognitive abilities, specifically their prior knowledge, goals, and commitments to the desired outcome. In addition, the theorist explored how internal and external factors affect students’ collegiate experiences. The Student Integration Theory describes and presents four stages that explain why a student leaves an institution due to how a student interacts with the college process (see Figure 1). The theorist’s model includes three primary sources for student departure: “academic difficulties, the inability of individuals to resolve their educational and occupational goals, and their failure to become or remain incorporated in the intellectual and social life of the institution” (Tinto, 1993, p. 2). Tinto’s model serves as a social system of stages through which students uniquely move through, encountering barriers while attending the institution. For example, standardized exams, such as the SAT and ACT, present a barrier for high school students who perform poorly on tests and may then contribute to a low College GPA and possibly dropping out.

Figure 1.

Revised Student Integration Model for First-Year Undergraduate Students.

Tinto’s first stage, pre-entry attributes, consists of family background, skills and abilities, and prior school, all of which contribute to a student’s identity and affect how they interact with the external experiences of college (Tinto, 1993). Family background establishes who a student is, their race and culture, and if they identify as low-income or first-generation. The other pre-entry attributes, skills and abilities, and prior schooling outline students’ academic history and strengths and weaknesses. High school students’ skills, abilities, and prior schooling go hand-in-hand as they prepare for college. Tinto’s pre-entry attributes contribute to academic development, such as maintaining good grades and studying for standardized tests, to achieve goals and set intentions for the college transition.

The variables studied in the proposed research align with Tinto’s Student Integration Model by addressing student characteristics and academic achievement variables (See Figure 1). Pre-entry attributes of being Students of Color, having First-Generation Status, and Pell Eligibility all extend throughout a student’s collegiate experience and ultimately impact their early success due to their family and academic histories. For example, students of color may grow up in households with little financial support to fund their education (Bowman & Bastedo, 2018; Camara & Mattern, 2022). First-Generation Students derive from families who have not attended college; the students are the first to participate in college in the family (Davis, 2010). As a result, First-Generation Students and their families may need to be better informed about the college search process (Davis, 2010). Those who are Pell-Eligible are students who may come from low-income backgrounds and do not have sufficient funds to assist with institutional costs. Pell Grants are only awarded to students with financial need (Federal Student Aid, U.S. Department of Education, n.d.). Students awarded the Pell Grant do not owe interest because grants do not require that money to be repaid.

Following the pre-entry attributes, the second stage is students’ goals and commitments to pursue college and become academically prepared to apply for colleges and scholarships. Under goals and commitments are the student’s collegiate intentions and institutional goals and commitments. According to Tinto, this section is critical as it predicts how well a student may perform once enrolled in college (Nicoletti, 2019). The Test-optional and pre-college credits closely align with students’ intentions to prepare for college in Tinto’s second stage. Students may decide not to submit a test score due to limited financial resources, poor academic performance, or poor test-taking ability. Choosing the Test-Optional option then affects how the student is reviewed in the admission decision. Concerning college preparation, students who enroll in pre-college credits are exposed to college rigor early. Pre-college credits can indicate that students will do well in college (Manno, 2024). Next, students’ high school academic achievement, such as high school GPA and taking the SAT or ACT, also closely aligns with the second stage, under goals and institutional commitments. High school GPA is a cumulative indicator of whether a student is performing well or not in their courses. Overall, good standing in high school achievement will better prepare students for the college transition (Zwick, 2007). Standardized tests, like the SAT and ACT, are taken during high school and are a requirement based on each state. The SAT and ACT can be critical as students are expected to know the content covered in those tests (Zwick, 2023). In addition, the SAT or ACT is one criterion for college applications, and students must decide whether they want to submit their scores (Cai, 2020).

The third stage in Tinto’s model is institutional experience, which addresses how a student experiences the academic and social systems of the university, including academic collegiate performance, faculty interactions, participation in extracurricular activities, and peer relationship building. Institutional experience and integration in Tinto’s model are significant predictors of whether a student remains (Nicoletti, 2019). Students’ institutional experience is significant because of formal and informal involvement in their academic program and other college experiences. Pursuing their education and living on a campus for four years, the environment must be comfortable to ensure they learn and live safely. Academic and social integration go together because students find their cohort of peers in their program, who become safe spaces, too. Finding groups of peers with the same interests and goals provides students with security in knowing they belong at their institution. The social system of the institution offers a safety net for students by establishing a place of belonging for their academics, relationships, and mental and physical well-being (Nicoletti, 2019). With all of these factors, students are likely to succeed.

Tinto’s fourth stage addresses goals and intentions to obtain a four-year degree on time and a full-time job upon graduation. Just like the second stage of Tinto’s model, students intend to complete their college degrees to move on to the next stage of their lives. Furthermore, the goals and commitments consider students’ institutional experience and integration, how well they did, and the state of belonging they could build (Nicoletti, 2019). Students must be intrinsically motivated to learn the content of their major and earn high grades in coursework. However, during their years in college, some students may decide to change their outcome and drop out. Students may drop out for many reasons: lack of financial aid, mental health issues, poor academic performance, transfer to a different institution, and lack of emotional and social support (Heubeck, 2024). With all of these factors in mind, student drop-out could happen any time, or even suddenly, while at the institution.

In applying Tinto’s Student Integration Model, this framework provided reasoning for the independent and dependent variables examined in this study. Understanding how students’ family backgrounds contribute to their academic success and retention is critical. Students’ demographic backgrounds can provide a glimpse into their upbringing, such as family income and school districts attended, as a means of better understanding their academic history. Student characteristics and academic achievement factors were examined as the independent variables predicting undergraduate first-year GPA. As such, this study also utilized these independent variables as factors that may increase the likelihood of dropping out of college within the first year. As a predictive model, Vincent Tinto’s Student Integration model provides a significant foundation for students’ progression through high school, institutional experiences, and degree completion (Nicoletti, 2019). Each variable is relevant to students’ progression as these variables affect each stage of the model and the outcome.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This correlational study utilized a secondary dataset from institutional records of first-year undergraduate students who entered in the fall of 2023 and transitioned from high school to college. The researchers submitted a specific request for data points on all entering undergraduates for the academic year of 2023–2024 from the Office of Institutional Research. All data were anonymous.

The studied university has an undergraduate enrollment of approximately 15,900 students. According to the Office of Institutional Research, 57.4% are females, 16.4% are minority students, and 2.7% are international students. In addition, the mid-size institution represents just 16.4% of minority students, while the non-minority students constitute 77.7%. Most students who attend this institution reside in-state, while 17% come from out-of-state areas. The university has an 81% admissions rate, with 21% choosing to attend.

2.2. Research Questions and Data Analysis

This study explored two research questions. The variables are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Measurement of Independent and Dependent Variables.

- Which student characteristics (Students of Color, First-Generation, and Pell-Eligible) and academic variables (Test-Optional, High School GPA, and Pre-College Credits) best predict GPA among first-year undergraduate students?

- Which student characteristics (Students of Color, First-Generation, and Pell-Eligible) and academic variables (Test-Optional, High School GPA, and Pre-College Credits) increase the odds of first-year college completion among first-year undergraduate students?

Pre-analysis data screening was completed to address outliers and missing data. Data were screened for linearity, normality, homoscedasticity, and multicollinearity and fulfilled assumptions (Mertler et al., 2022). Descriptive statistics were generated for all variables to describe the sample. Research question one was analyzed through forward multiple regression, which is to “model or group variables that best predict a criterion variable (DV)” (Mertler et al., 2022, p. 205). To gain a better understanding of the relationships between the independent variables and the dependent variable, we conducted further analysis using a correlation coefficient matrix and t-tests of independent samples.

Research question two utilized binary logistic regression to examine which student variables increase the odds of first-year completion. Frequencies of the dependent variable were generated to examine group sizes. The dependent variable was dichotomous: coded 0 (did not complete the first year) or 1 (did complete the first year). We chose to conduct further analysis to explore first-year completion differences by using t-tests of independent samples and chi-square tests of independence.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The averages of several academic achievement variables for the total sample are presented in Table 2. High School GPA generated a mean of 3.49, while College GPA averaged M = 3.25. Of the total sample, 86.4% reported having Pre-College Credits before entering college. Pre-College Credits may include College Credit Plus courses, AP courses, Dual Enrollment courses, or other college-related programs completed in high school. Of the 2278 students who submitted their ACT scores, the average mean was M = 22.7. Of the total sample, 16.4% (n = 592) submitted their SAT scores for college admission, while 63.2% submitted their ACT scores.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Academic Achievement Variables.

Frequencies and percentages were generated for the categorical variables: Student of Color, First-Generation Status, Pell Eligibility, use of test scores, and first-year student completion. Of the 3602 first-year students, 2839 (78.8%) identified as White, while 678 (18.8%) identified as a Student of Color. Eighty-five first-year students did not specify their ethnicity. In addition, 636 first-year students (17.7%) identified as First-Generation Status; students who were Pell-Eligible and displayed financial need consisted of 28.1% (n = 1101) of the sample. Regarding those who used the Test-Optional policy, 858 (23.8%) first-year students did not apply with a test score, while 2744 (76.2%) did apply with an ACT or SAT score. In examining first-year student completion, 2910 (80.8%) completed the first year of college, while 692 (19.2%) discontinued enrollment at some point during their first year.

3.2. Inferential Results for Research Question 1

A t-test of independent samples was first conducted to examine group differences based on the use of Test-Optional on the academic variables (see Table 3). Since Test-Optional was not a significant predictor of early college success, further analysis was necessary. The results revealed that those who submitted their test scores for admission had significantly higher High School and College GPAs than those who did not. Those who submitted test scores enrolled in more pre-college credits (M = 11.31) than those who did not submit test scores (M = 5.28). Test-Optional had a large effect on the academic variable of High School GPA (Cohen’s d = −0.904), a moderate effect on Pre-College Credits (Cohen’s d = −0.433), and a small effect on first-year College GPA (Cohen’s d = −0.160). Interestingly, students choosing not to submit a test score for admissions have a much lower High School GPA than those who submit.

Table 3.

T-test Results by Test-Optional.

Forward multiple regression was conducted to determine which student characteristics and academic achievement variables best predict undergraduate first-year student GPA. The analysis produced a five-variable model—F(5, 2774) = 258.37, p < 0.001, with a large effect size R2 = 0.318—including High School GPA, Pell Eligibility, Student of Color, Pre-College Credits, and First-Generation Status. Test-Optional was not a significant predictor in the model. A correlation matrix was created to better understand how the independent variables related to each other and first-year College GPA (see Table 4). First-year College GPA was moderately correlated with High School GPA (r = 0.543), followed by Pre-College Credits (r = 0.267). High School GPA was the best predictor of undergraduate first-year GPA, accounting for 29.5% of the variance in first-year College GPA. Students of Color (r = −0.168), Generation Status (r = −0.118), and Pell Eligibility (r = −0.193) were negatively and weakly related to first-year College GPA. These results reveal that first-year College GPA decreases when being a Student of Color, Pell Eligible, and/or having First-Generation Status. Since Test-Optional produced a very weak correlation with first-year College GPA (r = 0.096), it was not included in the predictive model. The regression equation generated for the model predicting first-year College GPA is as follows:

Y = 0.527 + 0.751XHSGPA − 0.147XPE − 0.137XSofC + 0.003XPCC − 0.084XFG

Table 4.

Correlation Matrix of Studied Variables.

3.3. Inferential Results for Research Question 2

T-tests compared (n = 2908) first-year completers and (n = 691) non-completers for the academic variables (See Table 5). The results revealed that completers have higher High School and College GPAs and more Pre-College Credits than non-completers. With a large effect size, first-year student completion (Cohen’s d = 1.30) had a very large effect on first-year College GPA. Student completion had a moderate effect on High School GPA (Cohen’s d = 0.459) and Pre-College Credits (Cohen’s d = 0.343).

Table 5.

T-test Results by First-Year Completion.

Binary logistic regression was conducted to determine which independent variables increase the odds of undergraduate first-year student completion (see Table 6). Forward Wald criterion was utilized to generate a significant four-variable model including High School GPA, Pell Eligible, First-Generation Status, and Pre-College Credits as predictors of first-year student completion: −2 Log likelihood = 2696.14, c2(4) = 233.34, p < 0.001. Although the model was significant, it only explained 12% of the variance in the dependent variable of first-year completion (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.120) and achieved 81% classification accuracy. The results indicated that High School GPA was the strongest predictor of first-year student completion. As High School GPA increased by one point, the odds of completing tripled; odds ratio = 3.04. Being Pell Eligible (odds ratio = 0.65) and First-Generation Status (odds ratio = 0.67) decreased the odds of completing the first year. The odds ratio of one for Pre-College Credits indicated minimal association with first-year completion.

Table 6.

Binary Logistic Regression Coefficients of the Model Predicting First-Year Completion.

To examine the relationship between first-year student completion and the categorical variables of Test-Optional and Student of Color, a chi-square test of independence was conducted. The results revealed that 81.8% of those who did submit a test score were first-year completers, while only 77.5% of completers did not submit a test score (See Table 7). Of Students of Color, only 74.2% completed the first year compared to 82.4% of White students. Students of Color may not have completed due to internal and external factors that these data does not present. The difference in completion rates between White students and Students of Color is statistically significant; White students are more likely to complete χ2 (1) = 23.50, p = 0.005.

Table 7.

Chi-Square Results by First-Year Completion with Observed Percents.

The chi-square test was also conducted to analyze the association between Test-Optional and Students of Color, First-Generation Status, and Pell Eligibility (see Table 8). Results revealed that Students of Color were less likely to submit their test scores (61.4%) compared to the 79.6% of White students who did submit test scores for admission. In contrast, First-Generation Status did not differ in the submission of a test score. Pell-Eligible Students were more likely not to submit a test score for admission when compared to their counterparts. Those who were not Pell Eligible (n = 22.9%) were slightly less likely to use the Test-Optional Policy than those who were Pell Eligible (n = 26.1%). It can be concluded that Students of Color and Pell-Eligible Students are more likely to use the Test-Optional Policy than White-identifying and non-Pell-Eligible Students.

Table 8.

Chi-Square Results by Test-Optional with Observed Percents.

4. Discussion

4.1. Test-Optional

Test-Optional was not included in the model to predict first-year student achievement. The Test-Optional variable produced a weak correlation with first-year College GPA (r2 = 0.096), with little to no effect on academic achievement. Students who did not submit a test score for admissions had a lower High School GPA (M = 2.94) than those who did submit a test score (M = 3.66). In addition, Test-Optional negatively correlated with Students of Color and Pell-Eligible. Similarly, those who did not submit a test score also enrolled in fewer Pre-College Credits in high school (M = 5.28). Those who did not submit a test score may not have performed well on those standardized exams, therefore not wanting the score to be considered in the admission decision. In sum, Test-Optional was not a significant predictor of College GPA or first-year completion. However, the variable of Test-Optional is one of selection by the incoming student, whereby many external variables may contribute to such a decision. This study did not account for such variables (e.g., test preparation, test access, parental involvement, peer effects, school counselor engagement, etc.), which is a limitation that may have altered the results. Future research may include such potentially confounding variables.

Chi-square results indicated that 77.5% completed the first year among those who did not submit a test score for college admissions, while 22.5% were not first-year completers. Chi-square results also revealed that Students of Color and Pell-Eligible Students were more likely to use the Test-Optional policy for admission. Being a First-Generation Student did not affect a student’s choice to apply with a test score or without. Concerning prior research, no definitive impact has been examined closely on the test-optional policy and its relationship with first-year student success and completion. However, studies have been conducted about the test-optional policy, concerning different factors such as student population and institution type, to examine if this policy positively impacts these factors. Researchers like Christopher T. Bennett focused on the Test-Optional policies at private institutions between the years 2005–2006 compared to 2015–2016 and how this policy supported diverse student populations and Pell Grant recipients (Bennett, 2022). Bennett’s study discussed the potential of the test-optional policy and how it could benefit diverse student populations and institutional enrollment. The results of Bennett’s analysis revealed that the test-optional policy increased college applications, but the authors did not find evidence of increasing yield rates. Secondly, Bennett found that the test-optional policy did increase enrollment of Pell-Eligible Students. Maintaining the test-optional policy would benefit the diversity of institutions, considering the recent changes in Affirmative Action and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

In turn, Schultz and Backstrom (2021) discussed the emergence of the test-optional policy, especially during the pandemic. The researchers examined the future of the test-optional policy, specifically highlighting public institutions in New York. The researchers focused on SUNY Potsdam, an institution that enacted the Test-Optional policy in Fall 2021. The results revealed that applications did increase with the implementation of the test-optional policy. However, the test-optional policy did not affect SUNY Potsdam’s acceptance rates and did not increase enrollment. SUNY Potsdam did have an increase in diverse student populations because of the Test-Optional policy.

While our research was conducted with a public institution, Bennett (2022) explained the need for further research on Test-Optional policies and how they can positively support diverse student populations. Schultz and Backstrom even explain, “Large-scale analysis of enrollment trends in public institutions is understudied” (p. 14). Further research on the Test-Optional policy needs to be further completed because this policy affects college admission decisions and student success, as well as merit scholarships, which are factors that college admission leaders must consider when discussing the future of Test-Optional policies (p. 15).

Prior research has indicated that standardized tests have been emphasized in high school curricula since the 1900s and have also been used to measure college readiness (Bennett, 2022). The ACT and SAT have long been used to make college admission decisions, but they have also been barriers for students from low-income backgrounds and those who are not good test takers (John et al., 2024). In this regard, these standardized tests should be in question for stakeholders as to whether they serve as an effective indicator of college readiness and accurately measure student knowledge. The Test-Optional policy provides college access to populations like Students of Color and First-Generation Students for college admissions. In widening access, institutions that implemented the Test-Optional policy had not only overall increased enrollment but also increased enrollment of Students of Color, First-Generation Students, and Pell-Eligible Students.

4.2. Results in Relation to Tinto’s Student Integration Theory

Providing a framework for our study, Vincent Tinto’s Student Integration Model enhanced the analysis of and literature on students’ academic journey. Tinto’s theory and model addressed a student’s likelihood of persevering in higher education, directly related to student background and how well they integrate into an institution’s academic and social aspects (Tinto, 1993). Tinto’s model exemplifies a progression of factors that influence students’ decisions in high school and factors that affect their academic performance. In addition, the model explains student departure through stages of integration, underlining three leading causes for departure: academic challenges, undetermined educational and occupational goals, and challenges in engaging with institutions’ intellectual and social environments (Tinto, 1993). The results of this study support Tinto’s theory and the complexity of variables that predict early college success and first-year completion.

Pre-entry attributes of Tinto’s student integration model include family background, skills and abilities, and prior schooling (see Figure 1). This first stage represents who students are and their high school history. The independent variables, Students of Color, First-Generation Students, and Pell Eligible, are factors within students’ family backgrounds. In the most current model of Tinto’s theory, it is essential to note that Pre-College Credits and Test-Optional align with the second stage, students’ intentions while in high school. Enrolling in pre-college classes will better prepare students for college as they receive early exposure to college coursework. Deciding to apply Test-Optional determines how students will complete their college application and whether they must retake their SAT or ACT. Also in the second stage, high school students focus on doing well in their classes to ensure that their High School GPA is suitable for college applications. The stronger students perform in high school academia, the more likely they are to succeed during the college academic transition (Heubeck, 2024). Additionally, when considering college applications, students must prepare for the SAT or ACT, as this is a graduation requirement, but not a requirement for college admissions today.

Multiple regression and forward binary logistic regression examined the academic factors of (High School GPA, Students of Color, First-Generation Status, Test-Optional, Pell Eligibility, and Pre-College Credits) to predict undergraduate first-year GPA and completion. In analyzing Tinto’s model, High School GPA, which lies in the goals and institutional commitments of Tinto’s model, best predicts students’ first-year GPA and completion. In addition, several pre-entry attributes were negative predictors—placing students at risk of poor college performance and/or dropping out during the first year. However, each variable explained a small portion of the variance in College GPA. Even so, Students of Color and Pell-Eligible Students may need additional supports to be successful. While maintaining adequate grades and College GPA, college students rely on support from others (Ramírez-Martínez et al., 2024). If there is no support from faculty, staff, or peers, students may drop out due to not feeling comfortable within the institution’s community or feeling unsuccessful. Students would likely benefit from a first-year seminar that introduces students to various support structures that would facilitate commitment and integration and ultimately support retention.

Given the adapted Student Integration Theory model, the pre-entry attributes and goals/commitments during high school must be addressed more closely and strengthened. College readiness and preparation should be emphasized during students’ high school years to prepare them better when they transition to college. For high school students to perform well during high school, school leaders, such as classroom teachers, must focus on the students who are struggling to ensure they are successful. In addition, high school leaders should revisit the curriculum and assess what students need to know before entering college. The independent variable, Test-Optional, provides an alternative for students to submit their test scores or not for college admission. When applying to different institutions, students who do not perform well on the ACT and SAT are influenced by institutions that implement the test-optional policy in their admission processes. Students of Color and First-Generation Students will most likely apply to institutions with a test-optional policy, knowing they do not have the barrier of a standardized test to keep them from being admitted.

Regarding undergraduate first-year completion, High School GPA had the strongest correlation, followed by Pre-College Credits. Having a high High School GPA and Pre-College Credits enhances the student’s college experience and performance, as they are readily prepared for the next transition. If a student has come from a high school where they did not receive adequate resources to prepare academically, then their high school GPA will reflect that, as well as their College GPA. Per Tinto’s model, a student’s drop-out decision will stem from their institutional experiences and academic performance. Students may also drop out because they feel they do not belong in their community or on campus. In this regard, the adapted Tinto model provides extra-curricular activities and peer interactions under a student’s institutional experience. Specifically, Students of Color and First-Generation Students seek support services to feel a sense of belonging and resources to help them succeed academically (Ramírez-Martínez et al., 2024). All variables remain in the recently revised model because the student (Students of Color, First-Generation Status, and Pell-Eligible) and academic factors (High School GPA, Pre-College Credits, and College GPA) provide a significant understanding of students’ educational journeys. The preceding variables also provide critical attributes of a student’s transition from high school to college, with their academic and demographic history impacting their college transition during their first year.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study have provided a foundation for college readiness and the Test-Optional policy. First, the Test-Optional policy likely benefits Students of Color, First-Generation Students, and Pell-Eligible Students in college admissions but does not necessarily give them an advantage in first-year college performance and completion. Students of Color, First-Generation Students, and Pell-Eligible Students use the Test-Optional policy more than their counterparts. College admission leaders should consider keeping this policy to continue access to all student populations.

Consistent with past research, High School GPA is the best predictor of early college achievement and first-year completion. It will be critical for high school leaders to recognize the importance of preparing students for college and core academic skills. College readiness in high schools will need to be strengthened to reach all students’ learning styles and to prepare low-achieving students better (Manno, 2024). Low-achieving students will need more support and academic resources to improve and enhance their prior knowledge of content (Heubeck, 2024).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.R.O. and R.A.V.; methodology, R.A.V.; validation, K.R.O., R.A.V. and A.C.R.; formal analysis, K.R.O.; investigation, K.R.O.; resources, K.R.O.; data curation, K.R.O.; writing—original draft preparation, R.A.V.; writing—review and editing, K.R.O., R.A.V. and A.C.R.; project administration, K.R.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the Institutional Review Board waived the data used, a secondary data set from the institution being studied, and no human subjects were involved.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived due to the Institutional Review Board waived the data used, a secondary data set from the institution being studied, and no human subjects were involved.

Data Availability Statement

Not available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Allensworth, E. M., & Clark, K. (2020). High school GPAs and ACT scores as predictors of college completion: Examining assumptions about consistency across high schools. Educational Researcher, 49(3), 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, C. T. (2022). Untested admissions: Examining changes in application behaviors and student demographics under test-optional policies. American Education Research Journal, 59(1), 180–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, N. A., & Bastedo, M. N. (2018). What role may admissions office diversity and practices play in equitable decisions? Research in Higher Education, 59(4), 430–447. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/26451641 (accessed on 1 March 2024). [CrossRef]

- Cai, L. (2020). Standardized testing in college admissions: Observations and reflections. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 39(3), 34–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, W. J., & Mattern, K. (2022). Inflection point: The role of testing in admissions decisions in a postpandemic environment. Educational Measurement: Issues & Practice, 41(1), 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestau, D., Epple, D., Romano, R., Sieg, H., & Wajtaszek, C. (2023). How effective are colleges in educating a diverse student body? Evidence from West Point. Journal of Human Capital, 17(2), 250–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. (2010). The first-generation student experience: Implications for campus practice, and strategies for improving persistence and success (1st ed.). Stylus Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- FairTest. (2013). FairTest press release on 2013: Release of SAT scores. Available online: https://fairtest.org/SATscorerelease2013/ (accessed on 24 March 2024).

- Harris, J. L. (2020). Inheriting educational capital: Black college students, nonbelonging, and ignored legacies at predominantly white institutions. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 48(1/2), 84–102. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26979203 (accessed on 20 February 2024). [CrossRef]

- Heubeck, E. (2024, February 21). High school students think they are ready for college. But they aren’t. Education Week. Available online: https://www.edweek.org/teaching-learning/high-school-students-think-they-are-ready-for-college-but-they-arent/2024/02 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Hosler, D., Chung, E., Kwon, J., Lucido, J., Bowman, N., & Bastedo, M. (2019). A study of the use of nonacademic factors in holistic undergraduate admissions reviews. Journal of Higher Education, 90(6), 833–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research. n.d. The carnegie classification of institutions of higher education (2021st ed.). Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research.

- John, M., Swanston, B., & Clingenpeel, D. (2024, April 5). ACT vs. SAT: What’s the difference? Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/advisor/education/student-resources/act-vs-sat/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Lovell, D., & Mallinson, D. J. (2023). Pencils down… for good? The expansion of test-optional policy after COVID-19. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manno, B. (2024, May 28). Are high school graduates ready for college? Forbes. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/brunomanno/2024/05/28/are-high-school-graduates-ready-for-college/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Mertler, C. A., Vannatta, R. A., & LaVenia, K. N. (2022). Advanced and multivariate statistical methods: Practical application and interpretation (7th ed). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti, M. d. C. (2019). Revisiting the Tinto’s theoretical dropout model. Higher Education Studies, 9(3), 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, J. (2022). Inflection point: Is test-optional the future? Journal of College Admission, 255, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Martínez, F. R., Villanos, M. T., Sharma, S., & Leiner, M. (2024). Variations in anxiety and emotional support among first-year college students across different learning modes (distance and face-to-face) during COVID-19. PLoS ONE, 19(3), e0285650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, L., & Backstrom, B. (2021). Test-optional admissions policies: Evidence from implementations pre- and post-COVID-19. SUNY Rockefeller Institute of Government. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED613855.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2024).

- Schuyler, S. W., Childs, J. R., & Poynton, T. A. (2021). Promoting successes for first-generation students of color: The importance of academic, transitional adjustment, and mental health supports. Journal of College Access, 6, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Syverson, S. (2007). The role of standardized tests in college admissions: Test Optional admissions. New Directions for Student Services, 2007(118), 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. n.d. Federal student aid. Available online: https://studentaid.gov/ (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Zwick, R. (2007). College admissions in twenty-first-century America: The role grades, tests, and games of chance. Harvard Educational Review, 77(4), 419–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwick, R. (2023). The role of standardized tests in college admissions. A civil rights agenda for the next quarter century. U.S. Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).