1. Introduction

“The day-to-day operations of schools are becoming progressively influenced by legal decisions which have an overall effect on education and the legal rights afforded to all school stakeholders” (Davis & Williams, 1992; Reglin, 1992, as cited in

Petty, 2016, p. 26).

Davies (

2009) observed that “… educators are developing an increased sensitivity to the legal context that shapes their professional work” (p. 1). He also noted “Schools … are burdened with the ever-more difficult challenge of navigating themselves through the litigious labyrinth that is modern schooling” (

Davies, 2009, p. 1). Indubitably, schools are becoming more litigious mini-societies while simultaneously educators are having to increasingly deal with the legalisation of schools (

Newlyn, 2006;

Stewart, 1998). As a result, educators need to have an awareness and understanding of legal principles affecting education more than ever before (

Teh, 2014).

There have been some notable sagacious scholars who have written about education law (

Butler & Mathews, 2007;

Jackson & Varnham, 2007;

Mawdsley, 2012;

Orr, 2020;

Russo, 2019) and more specifically about legal literacy of educators (

Leete, 2022–2023;

McCann, 2006;

Stewart, 1996;

Teh, 2014;

Trimble, 2017). However, not a substantial amount has been written about the level of legal understanding captured by educators in Australia. Indeed,

Teh (

2014) stated “Little is known in Australia about the level of legal literacy held by teachers…” (p. 263). This has been an area of study left reasonably unexplored.

Stewart (

1996) conducted a study investigating the level of legal literacy developed by Queensland government school principals.

McCann (

2006), a decade later, inquired about the legal burdens encountered by Catholic school principals in Queensland.

Newlyn (

2006) investigated the degree of legal knowledge held by teachers in New South Wales government schools. More recently,

Trimble (

2017) considered the impact of legal issues affecting Tasmanian school principals.

The main aim of this research project was to develop a deeper understanding of the level of legal understanding held by Queensland independent school teachers. This study sought to do this specifically by considering a range of legal topics or areas in education law. This study involved research with a random group of teachers and middle leaders working in Queensland independent schools where the participants were asked to respond to a series of survey questions on a myriad of education law topics. It was found that the teachers surveyed, working in Queensland independent schools, had a low level of understanding of the legal principles that underpin their work in schools.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was a qualitative inquiry, investigating the level of understanding or sometimes referred to as legal literacy, that Queensland independent teachers possess (removed for peer review). This section highlights the steps undertaken in the collection of data whilst some consideration is provided outlining the elements of data analysis used.

A cross-sectional survey instrument was chosen for the study. This survey type involved a sample of respondents, aiming to represent the target audience and provide generalised findings (

Mills & Gay, 2019;

O’Leary, 2017). The survey targeted Queensland independent school teachers to assess their understanding of education law. Although not representative of all Queensland independent school teachers, the sample was intended to offer general conclusions about some teachers’ comprehension and application of education law in their professional roles.

The survey consisted of three distinct sections without labels or subheadings. The first section collected demographic data, including participants’ age, role in their school, and teaching experience. The second section contained five questions to gauge their self-perceived understanding of education law and their annual engagement with it. It also explored how their confidence in handling education law matters could be enhanced. One question asked participants to prioritise the most important education law issues they faced in their professional roles. Other questions in this section asked them to reflect on the most significant education law matters they encountered and rank the most useful ways to receive further training.

The third section included scenario questions, asking participants to outline the legal position on specific education law issues and explain their responses to demonstrate their understanding. The survey instrument was chosen over interviews to suit the intended analysis (

Mills & Gay, 2019). Participants completed the survey online, benefiting from advantages such as low cost, flexibility in question display, and automatic basic statistical analysis (

O’Leary, 2017).

Creating the survey instrument required careful consideration of the questions to elicit the desired data. Biases both on the part of the researcher and of the participants were avoided. All researchers bring a certain bias to their study. One author had the survey questions checked by other academics, and they were also piloted in a pilot study to remove all biases. Participants, too, have biases, and this can lead to data error. One author intentionally conducted the survey anonymously to reduce bias in their data collection. Questions were made clear to the intended audience (

Gray, 2018). Both structured and unstructured items were used (

Mills & Gay, 2019). Structured items required participants to choose among provided responses, while unstructured items allowed freedom of response to open-ended questions. The survey’s length was kept manageable to encourage participation (

Mills & Gay, 2019). The order of questions was adjusted to ensure a logical sequence (

O’Leary, 2017).

The survey was piloted with ten Queensland independent school teachers to gather feedback and improve the instrument. Feedback focused on question clarity, leading to improvements in reliability, especially for a couple of questions. Instructions were refined for clarity. Some questions were rewritten for accuracy (

O’Leary, 2017). The final survey was completed by forty-five participants, with further incomplete attempts excluded from the analysis.

Scenarios have been used in social science research since the 1950s to measure ethical reasoning and decision-making preferences (

Weber, 1992). Scenarios allow researchers to frame complex, multidimensional issues reflecting real-world decision-making (Cavanagh & Fritzsche, 1985, as cited in

Weber, 1992). The legal scenarios in this survey were based on real-life cases or legislative positions, and not simply made up. They reflected real incidents likely to occur in independent schools.

Scenarios demonstrate validity (

Weber, 1992). They highlight practical components of the social problem under review, namely, understanding education law. Scenario-based surveys allow researchers to identify relevant variables quickly (

Kokkinou & Cranage, 2011). Scenarios enable participants to demonstrate specific knowledge rather than a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response. They allow participants to apply their knowledge to real-life problems, showing a deeper understanding. This approach helps participants demonstrate true understanding by explaining their responses.

Measurement scales were used in the analysis of the data. Developing a scale is complex, even for experienced researchers (

Gray, 2018). Existing scales were considered, but new ones were developed for this project. This is mainly due to the fact that most scales that were found were more suited for quantitative studies and not qualitative ones, such as this study. Rating scales measured respondents’ attitudes toward themselves and their understanding of education law (

Mills & Gay, 2019). Rank ordering was used to compare values across variables, enabling respondents to prioritise traits or characteristics (

Cohen et al., 2018). These methods were suitable for a qualitative study, not requiring sophisticated statistical analysis (

Cohen et al., 2018).

For the demographic data and the second section of survey data, information was coded. A rating scale was used to analyse scenario responses, categorising participants’ understanding of education law from high to low. Five categories were used: high degree of legal literacy, some degree of legal literacy, confused legal literacy, incorrect legal understanding, and no understanding/left blank.

Content analysis was employed to analyse the collected data, following

Drisko and Maschi’s (

2016) model. Content analysis identifies categories within textual data through systematic coding, leading to contextual descriptions and limited quantification (

Maene, 2023). It analyses textual data using coding and categorisation to identify trends and patterns (

Brown & Scaife, 2019). This method was used to examine participants’ understanding of education law principles in the school context. A structured coding approach was used to identify trends in participants’ responses. The coding frame developed for this project was a continuum from high to no understanding of education law principles.

Qualitative data analysis can be conducted using computer programs, but manual analysis was chosen for this study to immerse the researcher in the data (

Adu, 2019). Content analysis can confirm theories, with researchers knowing what to look for in the data (

Brown & Scaife, 2019). This method generates narrative summaries highlighting important social problems (

Drisko & Maschi, 2016).

Content analysis explores both manifest and latent data. Manifest data is literal and easily seen, while latent data requires careful interpretation to uncover hidden meanings (

Bernard & Ryan, 2010). Coding steps recommended by Mayring (2007, as cited in

Panke, 2018) were followed. Specifications for each category were developed, applied to a sample set, and adjusted for the entire data set. The coding scheme was refined to capture the phenomenon of interest accurately (

Panke, 2018).

The coding scheme was adjusted from seven to five categories for a better fit. Categories were developed before fully exploring the data, focusing on dimensions of interest (

Maene, 2023). A suitable coding scheme was developed for this study, targeting research aims. Definitions for each category were created (

Maene, 2023).

Five categories were used to analyse scenario questions: high degree of legal literacy, some degree of legal literacy, confused legal literacy, incorrect legal understanding, and no understanding/left blank. The first category indicated a high level of legal literacy, with correct answers and explanations. The second category showed some legal literacy, with correct answers but no legal explanation. The third category indicated confused legal literacy, with correct answers but incorrect legal explanations. The fourth category showed incorrect legal understanding, with inaccurate answers and misapplied legal principles. The fifth category included blank or irrelevant responses.

Interpretive content analysis uses descriptive coding, allowing connotative categories based on symbolic meanings (

Drisko & Maschi, 2016). Categories developed for this coding process were clear, distinct, and based on specialised knowledge (

Drisko & Maschi, 2016).

3. Results

The third, final, and most determinative section of the survey instrument used to collect data for this project consisted of education law scenarios. These scenarios, based on real-life case law or legislative provisions enacted in schools, asked the participants for a short response about various aspects of education law and to answer what the legal position was in the specific issue under review and to explain why it was the case. This was so that a more accurate and true understanding of the level of legal literacy could be garnered. If participants could have easily said either “yes” or “no” without having to demonstrate knowledge, it is impossible to say with any level of certainty whether or not they hold a legal understanding of the issue. A total of 14 scenarios were used in the survey instrument. Whilst sixty-one participants completed the first two sections of the survey, only forty-five managed to complete the scenarios section. Some of the scenarios created were more the remit of the principal, who has overall responsibility for the global running of the school. Whilst many others were appropriate for teachers, as they have the responsibility of that particular decision in their classes. For example, scenarios 2 and 4 were essentially geared toward the school principal making these decisions and therefore part of their legal literacy required. Moreover, 12 of the 14 scenarios were most pertinent to the classroom teacher and the legal understanding that they needed to properly fulfil their professional duties.

All participant responses were coded according to the established codes, discussed above. They ranged from demonstrating a “high degree of legal literacy” to displaying “no understanding” or the answer was “left blank”. This same continuum was used to code all 14 scenarios.

3.1. Duty of Care Scenarios

Due to the fact that the duty of care covers such a wide array of topics and subtopics, in addition to being the most litigious area in education law, there were more scenarios dedicated to this topic. Scenarios 1, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14 covered various aspects of duty of care.

Table 1 portrays the results of the coded data from the duty of care scenarios. As with most of the scenario responses, there was a range of results evident. Nearly 74% of all responses for this topic were either “incorrect” or demonstrated “no understanding” of the relevant legal principles.

3.2. Student Protection and Mandatory Reporting Scenarios

Student protection and mandatory reporting are often combined into one area of education law, as there is considerable overlap between the two. The obligations in relation to mandatory reporting stem from the provisions of the

Child Protection Act 1999 (Qld). Teachers and school principals are deemed ‘mandatory reporters’ along with other particular professionals who have certain responsibilities to report suspected or actual child abuse and neglect to Child Safety.

Table 2 shows the results from the two student protection and mandatory reporting scenarios. These scenarios were answered better than all of the other categories, and one in particular was responded to with more positive results than any other individual scenario. However, nearly 69% of responses were still coded as either showing “confused legal literacy”, “incorrect legal literacy” or having “no understanding”.

3.3. Family Law Scenario

Due to the increasing divorce rates in this country (

Hewitt et al., 2005), family law and its associated education law matters are also on the rise. Therefore, it is considered important that educators are kept abreast of the changes and legal obligations in this area. Scenario 2 focused on what happens when divorced parents disagree about which school or even which type of school they wish their child to attend. It is usual in family law matters to first establish if there are any court orders or family plans in place. If so, it is prudent for the school to follow such orders/plans. However, this situation was asking more than that standard response.

Table 3 shows the coded results from this scenario.

It was positive to see that two respondents (5%) presented responses that showed a “high degree of legal literacy”. A further 24% of participants demonstrated “some degree of legal literacy”. Twenty-two per cent were coded as presenting “confused legal literacy” which overall indicated that this scenario was the one that was ‘better answered’. Despite this, 36% of participants had “no understanding” of the scenario.

3.4. Criminal Law Scenario

Scenario 3 focused on aspects of criminal law and what educators can, in fact, legally ask students to show various aspects of their property or to search. In this case, it asked about their uniform pockets and school lockers.

Table 4 outlines the results from scenario 3. Eighteen per cent of respondents coded as having “some degree of legal literacy”, while a further 40% were considered as demonstrating an “incorrect legal understanding” of this matter.

3.5. Discrimination Law Scenario

In the often acrimonious area of discrimination law, education is a keen player as schools are often tasked with making key decisions about a child’s education that can appear to be detrimental in achieving their long-term aspirations. Education is an ‘area’ under each piece of legislation in this country, at both state and federal levels, making it illegal to discriminate in the provision of this service (educating children) under the prescribed grounds (for example, sex or impairment) that are covered in the various enactments. Scenario 4 asked the survey participants whether or not it was regarded as discrimination if an impaired student was expelled from the school who acts in a dangerous manner due to his disability in and around other students.

Scenario 4 results are captured in

Table 5. Out of all the scenarios used in the survey for this study, these outcomes are the most ‘balanced’ or evenly spread across all of the categories in the coded results. Leaving aside “high degree of legal literacy”, the other four categories received a more even spread of responses than in all other scenarios. “Incorrect legal understanding” was the largest group with 29% of respondents, but only just, with “confused legal literacy” and “no understanding” both close with 26.5%.

3.6. Professional Conduct Scenario

All teachers have to meet professional expectations of behaviour both inside and outside of their school environment. These are, to a large extent, externally imposed by the respective teacher regulatory authority in the state or territory in which the teacher is working. A teacher has to be considered a person ‘fit and suitable to teach’ (

Queensland College of Teachers, 2019) and not be an unacceptable risk of harm to children (

Queensland College of Teachers, n.d.), while not exhibiting behaviour below the standard expected of a teacher (

Queensland College of Teachers, 2017). These professional behavioural expectations also often form part of the contract of employment when agreeing to work in an independent and/or faith-based school, just as the participants in this study were.

Scenario 6 dealt with this issue of professional conduct of teachers. This situation puts the teacher in the precarious position of questioning whether or not a teacher friend, who was also a fellow colleague working in their school, engaging in unprofessional conduct can be taken at his word, who was denying any inappropriate behaviour.

In this scenario, there was again a mix of outcomes from the responses. However, a sizeable 60% of respondents were coded as “incorrect legal understanding” (see

Table 6). There was one response that showed a “high degree of legal literacy” with a further three participants demonstrating “some degree of legal literacy”.

3.7. Privacy Law Scenario

Privacy and its concomitant mandatory data breach notification laws have been in the public vernacular in recent years, following substantial data breaches of privacy. Some of these concerned a major telecommunications company, a medical insurance company here in Australia, along with schools such as Fairholme College, Toowoomba, being caught up in data breaches. Privacy is perhaps not the most awakening area of education law, but the penalties and consequences for breaches can be gigantic, of up to AUD 1.8 million (

Butlin, 2022), not only in terms of financial loss but also, and sometimes more devastatingly, in reputational damage caused. Scenario 7 asked the survey participants if sharing of personal information to another school, despite it being part of the usual educational program amounted to a breach of privacy.

The majority of respondents were incorrect regarding this scenario, with 60% of responses amounting to an “incorrect legal understanding” of the issue. However, 9% of participants showed some true understanding of the issue and were coded as having “some legal literacy” concerning this question.

Table 7 breaks the results down in more detail.

3.8. Consumer Protection Law Scenario

The final scenario used in this survey centred around the legal obligations and protections of the federal consumer law. It asked survey participants whether or not making promises in school statements and then not living up to them can be legally treacherous.

The responses were shared amongst the usual four categories, with the largest number in the “no understanding/left blank” code at 40%. The second prominent group were “incorrect legal understanding”, accounting for 29% of responses.

Table 8 displays the results from this final scenario.

3.9. Overall Observations About the Data

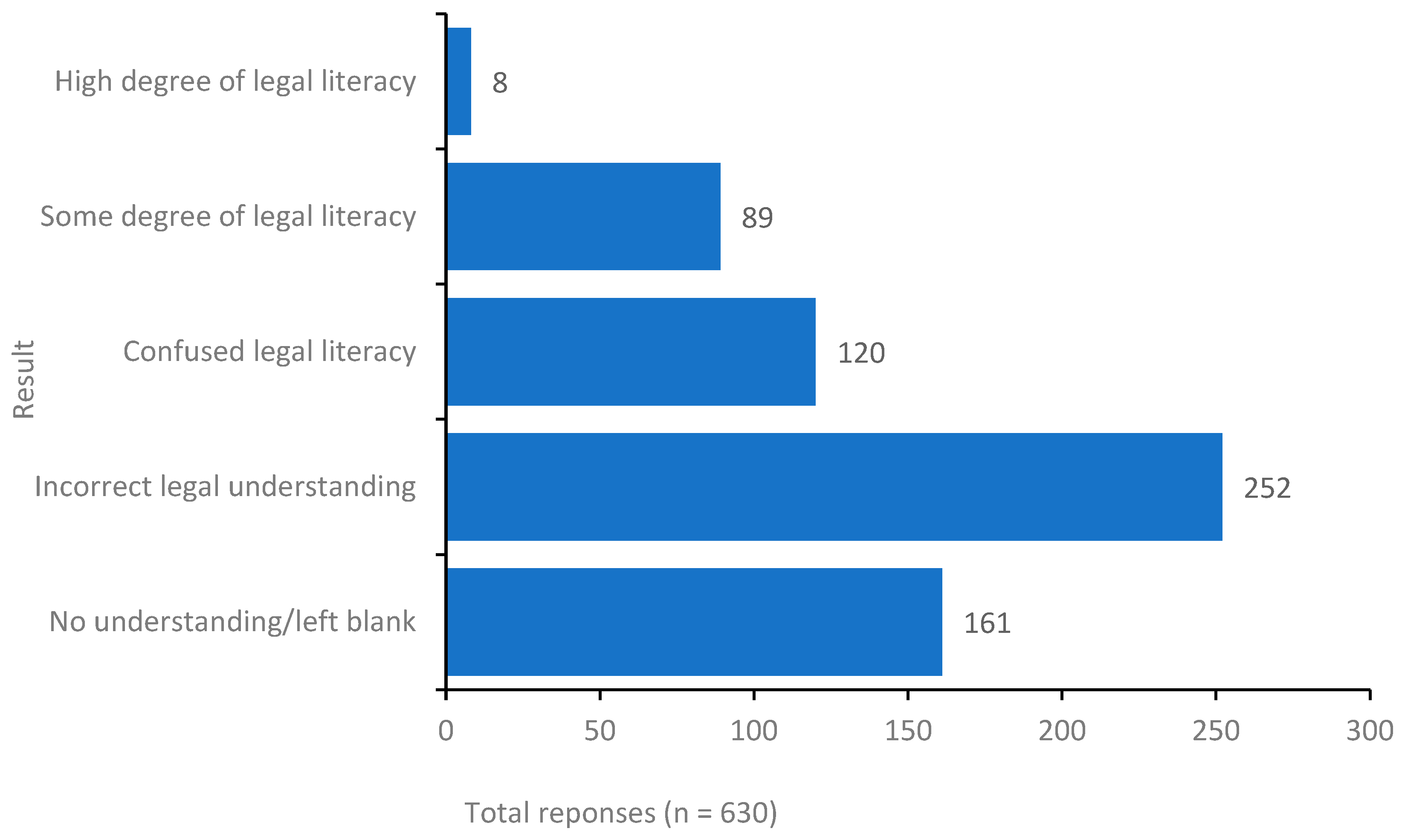

Table 9 and

Figure 1 show the total number of each coded response across the 14 scenarios.

The overall trend of the data would suggest that, overwhelmingly, Queensland independent school teachers have, at best, a confused understanding of education law for their everyday jobs. Remembering that “confused legal literacy” meant that teachers answered the ‘yes/no’ aspect of the scenario question correctly, but could not correctly identify, with any degree of certainty, the legal justification. Perhaps more accurately, it may be deduced from this table and the figure above that Queensland independent school teachers have a more incorrect understanding of the law as it pertains to their roles in schools. This is, at best, problematic, as it is incumbent on us, as educators, to have some correct understanding of education law matters. This is to help in risk minimisation while also attempting to avoid expensive litigation, both in terms of financial implications and reputational damage.

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion of the Results

The duty of care of students by their teachers is a fundamental aspect of education law. Six scenario questions in the survey focused on this topic. Scenario 1 (see

Appendix A for a list of all scenarios used in this research project) dealt with playground duty supervision, a common task for Australian teachers. Teachers must arrive on time, actively supervise students, and intervene when necessary, avoiding distractions like mobile phones. Over half of the participants either answered incorrectly or did not respond. Only three participants were somewhat correct. Many incorrectly suggested that Bill would be liable, failing to recognise that under vicarious liability, the school authority is ultimately responsible for lawful staff actions. This indicates a lack of understanding among teachers about their duty obligations and liability.

Scenario 10 examined whether teachers have a legal duty to intervene in student fights. Despite the potential physical threat, the law requires teachers to act and attempt to de-escalate the situation, even if it means only using a commanding voice. Over 50% of respondents misunderstood this requirement, with 75% either providing incorrect answers or not responding. Most participants believed they did not need to intervene if concerned for their own safety, contrary to case law. Teachers must understand their higher duty to care for students’ safety.

Scenario 11 questioned if teachers can be sued for ineffective teaching, a duty of care issue related to negligence. While rare cases in Australia have attempted to hold teachers liable for negligent teaching, none have succeeded. Courts recognise that many variables influence a student’s education, making it difficult to attribute a student’s academic performance solely to a teacher’s apparent negligence. Over 75% of participants provided incorrect responses or none at all. This concern about liability may deter teachers from engaging in extra-curricular activities, depriving students of valuable learning opportunities. The scenario also involved vicarious liability, where the school authority is ultimately liable for staff actions.

Scenario 12 explored the level of care teachers owe students in a Design Technology class. Despite explaining safety guidelines and providing equipment, the teacher must repeatedly intervene to ensure safety. A large percentage of teachers (67%) answered incorrectly, believing the teacher had done enough to avoid litigation. The high level of care required in such environments is crucial due to the inherent risks involved in these learning activities.

Scenario 13 asked if a teacher could be liable for leaving the classroom temporarily. Most participants incorrectly believed teachers should never leave the classroom under any circumstances. Courts have clarified that reasonable care, not total care, is required, and temporary absences do not necessarily amount to a breach of duty of care (

Barker v State of South Australia, 1978;

Butler & Mathews, 2007). Most participants (76%) answered incorrectly or not at all, showing a lack of understanding of legal principles in classroom injury cases.

Scenario 14 asked participants to consider factors making up the required standard of care in a classroom. Nearly 50% answered incorrectly, confusing risk assessments with the standard of care. Completing a risk assessment does not equate to meeting the standard of care, which involves considering all factors to ensure student safety.

Student protection and mandatory reporting are integral aspects of education law. Teachers must report suspicions of child neglect or abuse to the principal, as required by legislation (

Child Protection Act 1999 [Qld]). Scenario 5, concerning student protection, involved suspected child neglect with many participants confused or incorrect in their responses (31% under both codes). Teachers must report suspicions, not just investigate them. Annual professional development likely contributed to a better understanding in this scenario.

The second scenario under this topic, scenario 9, asked if discussing suspected child abuse with a deputy principal could have led to defamation. Teachers who report suspicions in good faith are protected from defamation or criminal liability (

Child Protection Act 1999 [Qld]). Participants showed better understanding in this scenario, likely due to mandatory annual training.

Family law matters affect schools, as children are unwittingly intertwined in family disputes. Scenario 2 asked what schools should do when divorced parents disagree on school choice. Schools should first ask parents to resolve the issue, possibly suggesting mediation (

Relationships Australia, n.d.). The scenario showed a slightly more balanced outcome, with 5% of participants demonstrating high legal literacy, representing the highest percentage of all scenarios.

Criminal law issues in schools include property destruction, assaults, theft, and illegal substance distribution. Scenario 3 questioned if teachers can ask students to show the contents of their pockets and lockers. Schools can ask students to show pocket contents based on reasonable suspicion, but lockers, as school property, can be inspected without permission (

Police Powers and Responsibilities Act 2000 [Qld]). Results were mixed, with many participants incorrectly suggesting parental permission was needed.

Discrimination law in schools often involves either employment or student enrollment matters. Scenario 4 asked if excluding a dangerous student with a disability is lawful. Courts consider the risk to others and whether the student is treated the same as others without the disability (

Purvis v New South Wales, 2003). Responses were balanced, with some participants considering the danger to others.

Professional conduct standards are high for teachers due to their role in safeguarding children. Scenario 6 asked if a teacher should report a colleague’s suspicious behaviour with a student. Teachers must report such behaviour to the principal, who then has a subsequent duty to report the matter to the regulatory body (

Education (Queensland College of Teachers) Act 2005 [Qld]). Most participants (60%) answered incorrectly, possibly due to a lack of senior management experience.

Privacy policies in schools regulate the collection, storage, use, and disposal of student information. Scenario 7 asked if sharing student information with another school for a dance event breaches privacy laws. Schools can share information for educational activities without parental permission, provided privacy obligations are met (

Privacy Act 1988 [Cth]). Many participants misunderstood this, confusing privacy with confidentiality.

Consumer protection law, including misleading advertising, applies to school enrolment contracts. Scenario 8 asked if promising all students would understand safety principles by the end of a unit is legally risky. Schools should use less definitive language to avoid misleading statements (

Competition and Consumer Act 2010 [Cth]). Results were mixed, with some participants showing a modicum of legal literacy.

4.2. Future Research Directions

Following on from the discussion of the results and their implications, there are a number of recommendations for future research. These are addressed below.

Recommendation 1: Introduce education law in initial teacher training.

It is suggested that universities or teacher regulatory bodies that externally accredit such programs consider the merits of introducing a unit or section of a unit on education law in all initial teacher training degrees to provide a solution to the lack of legal literacy held by teachers. Alternatively, attention could be given to this topic explored in in-service training for professional teachers as part of their professional development each year.

Recommendation 2: Compare other states and territories of Australia.

The first recommendation for future research is to consider other jurisdictions within Australia to discover the differences, if any, in their level of legal literacy. The scope of this project was limited to Queensland. It would be interesting to ascertain if other jurisdictions had similar or higher levels of legal literacy held by their independent school educators.

Recommendation 3: Consider and compare other sectors within Queensland.

Furthermore, it would be useful to research government school teachers or Catholic school teachers in Queensland and perform a comparative study between the sectors. Is the level of legal literacy of teachers in Queensland reasonably similar, or are there notable differences between the sectors? If there were discernible differences, further inquiry as to why that was the case would be a worthwhile study.