Rethinking Traditional Playgrounds: Temporary Landscape Interventions to Advance Informal Early STEAM Learning in Outdoors

Abstract

1. Introduction

STEAM Behaviors Supportive Playground Settings and Landscape Elements (Based on the Literature Review)

- How does evidence-based playground design (temporary landscape interventions) influence the frequency and diversity of children’s STEAM-related behaviors in informal learning environments?

- Which specific landscape elements and affordances most effectively support STEAM learning behaviors among preschool-aged children (ages 3–5) in a playground?

2. Research Method

- (a)

- Landscape Element Identification and Experimental Design:

- (b)

- Pre- and Post-Intervention Assessments:

- E-B Mapping is a method grounded in the delineation of researcher-defined activity zones within an outdoor play environment (Cosco et al., 2010; Morrissey et al., 2015). This approach entailed systematically documenting the frequency and nature of children’s STEAM learning behaviors as they occurred within the pre- and post-intervention playground settings. According to Cosco et al. (2010), this methodology facilitates an in-depth analysis of how specific design elements influence user behavior, enabling a nuanced understanding of “the behavioral dynamics of the built environment” (p. 514). It is particularly valuable for generating both qualitative and quantitative insights concerning the types and frequency of activities in relation to spatial features, thereby offering empirical evidence to evaluate and enhance outdoor design (Marušič & Marusic, 2012).

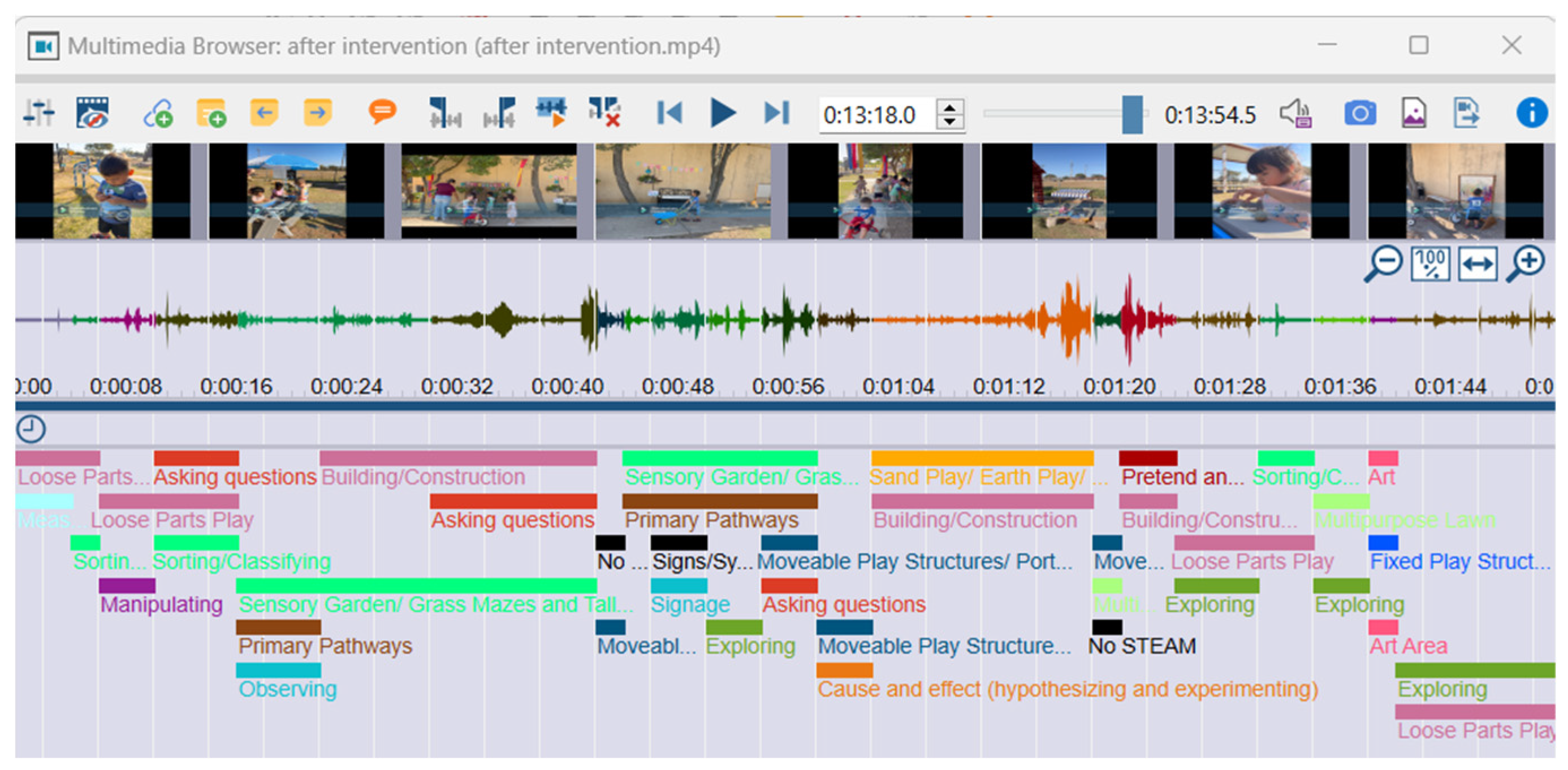

- In addition to E-B mapping, video data analysis was conducted to gain deeper insights into specific instances of children’s engagement with the temporary, evidence-based playground intervention. Children were video recorded for one hour on two consecutive days (30 min each) prior to the intervention and again for one hour on two consecutive days following the intervention during their unstructured free play at the selected site. A momentary time sampling method—also referred to as interval recording—was employed to examine behaviors at regular time intervals (Miller, 2010). For analytical consistency, the pre- and post-intervention recordings were segmented into 1 min intervals, and a 15 s segment was extracted from the end of each interval. This segmentation resulted in 181 behavioral observations before the intervention and 202 afterward. A qualitative content approach was used, with the MAXQDA 2022 software to code video recordings in line with the study’s research focus. Through iterative content structuring, observed behaviors were systematically assigned to specific or multiple STEAM-related categories based on predefined criteria.

2.1. Site Description—Guadalupe Learning Center, Lubbock, Texas

2.2. Existing Condition of the Playground

2.3. Evidence-Based Playground Design (Temporary Intervention)

| Intervention Elements * | Expected STEAM Learning Outcomes |

|---|---|

| Sand Play Structure (with shade and play tools) | Cause/Effect, Construction, Manipulative, Observation, Exploration |

| Water Play Wall (with play tools) | Cause/Effect, Construction, Manipulative, Observation, Exploration |

| Sensory Pathway (with steppingstones) | Observation, Exploration |

| Sensory Garden (with raised bed and climbing structure) | Observation, Exploration, Experiments, Natural Art, Counting, Sorting, Measuring, Comparing |

| Loose Parts Play (Acorns, Pinecones, Seed Pods, Tree Branches, Leaves) | Experiment, Exploration, Observation, Counting, Sorting, Measuring, Comparing |

| Wildlife/Bird, Butterfly, and Pollinator Habitat (with the bird bath and feeder) | Observation, Exploration, Language, Signs |

| Acoustic Play Settings (with tools) | Music, Language, Exploration, Observation, Teamwork, Signs |

| Art Area (with art wall and colors) | Art, Language, Exploration, Observation, Teamwork, Signs |

| Outdoor Classroom (with shade and seating) | Language, Literacy, Reading, Signs |

| Pretend and Performance/Decks, Platforms and Stages (teepee) | Performance, Signs, Language, Observation |

| Moveable Play Structures/ Portable Toys and Equipment (wheeled toys) | Diverse Affordances |

| Natural Healing and Relaxation Area (with sensory elements and plants) | Observation, Exploration, Experiments |

| Storage (with seating) | Diverse Affordances |

| Signage: Directional, Informational, Identification, and Inspirational signs | Language, Literacy, Reading, Signs |

2.4. Coding for Observation, Data Collection, and Data Analysis

3. Data Analysis and Findings

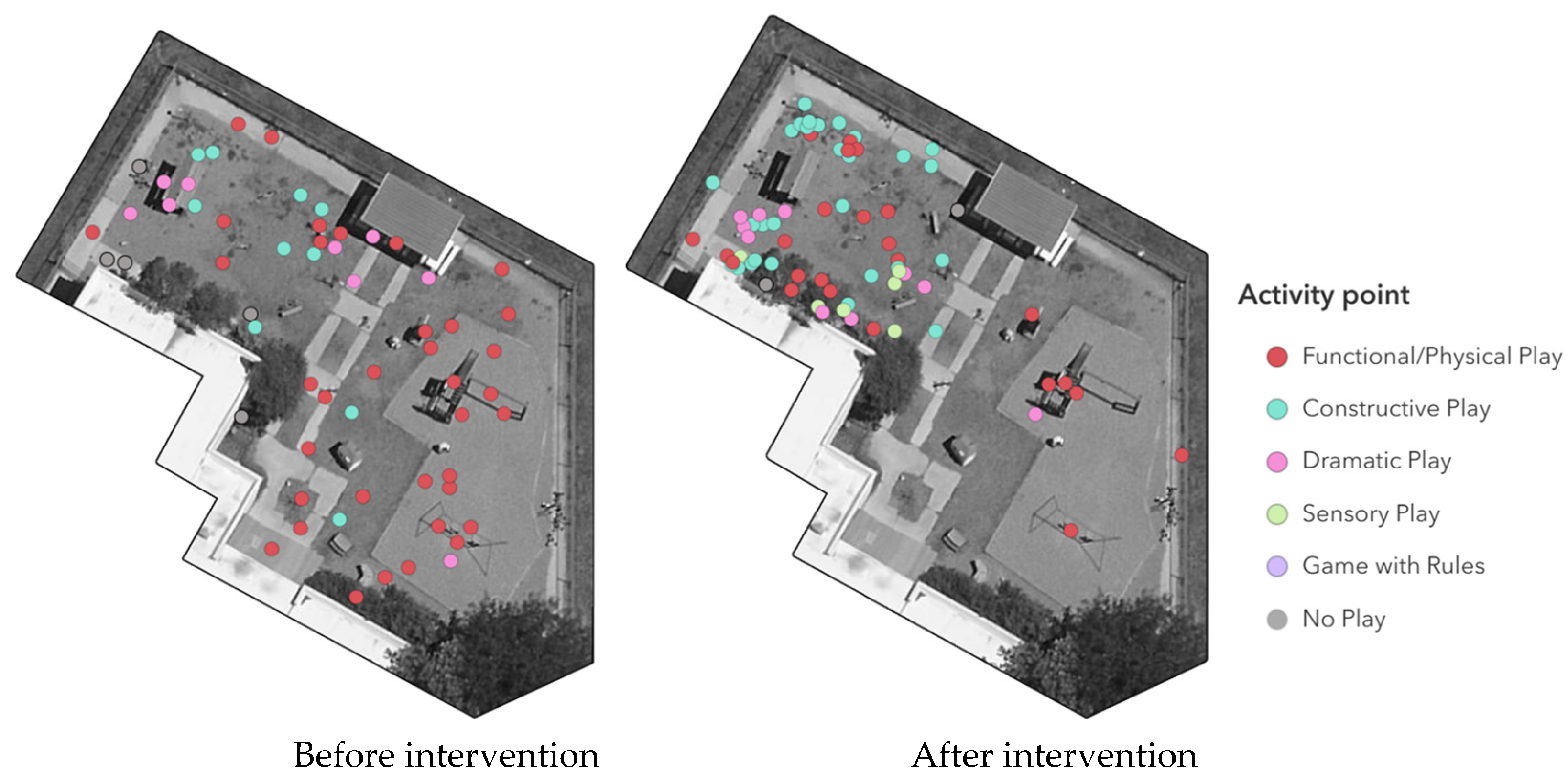

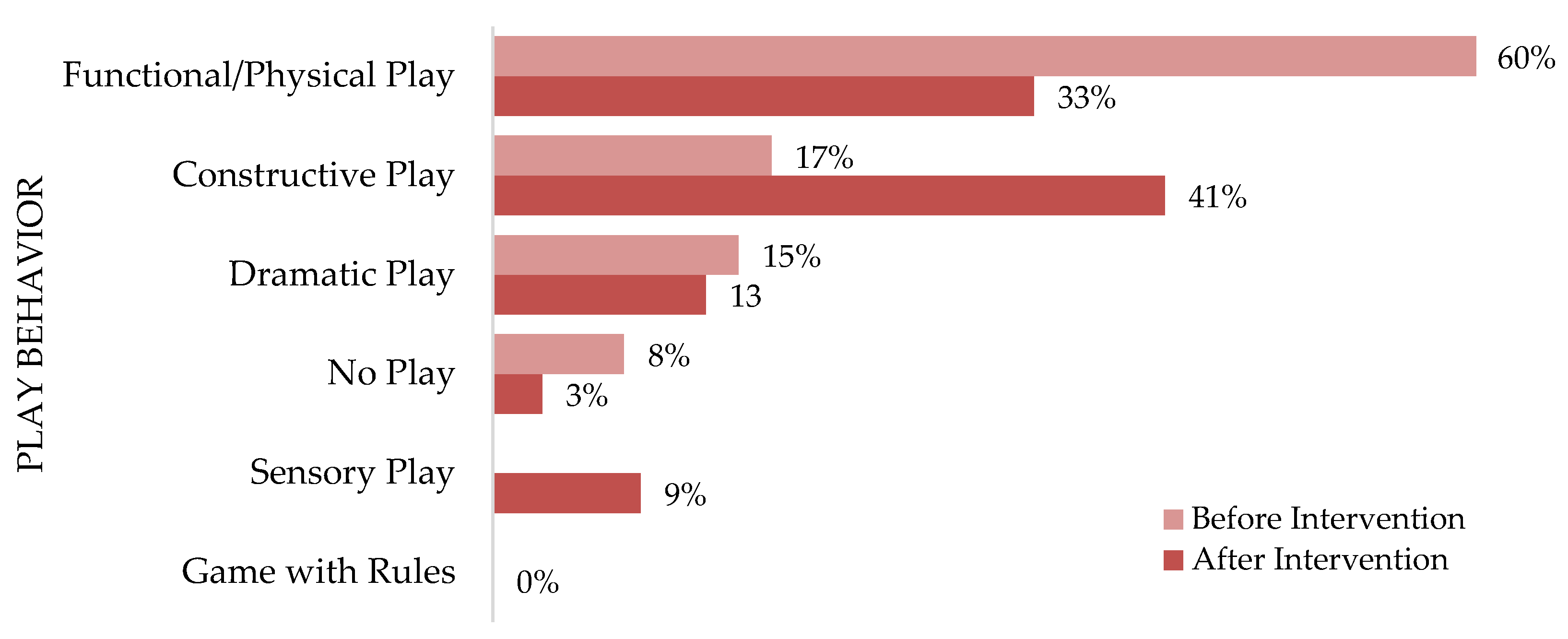

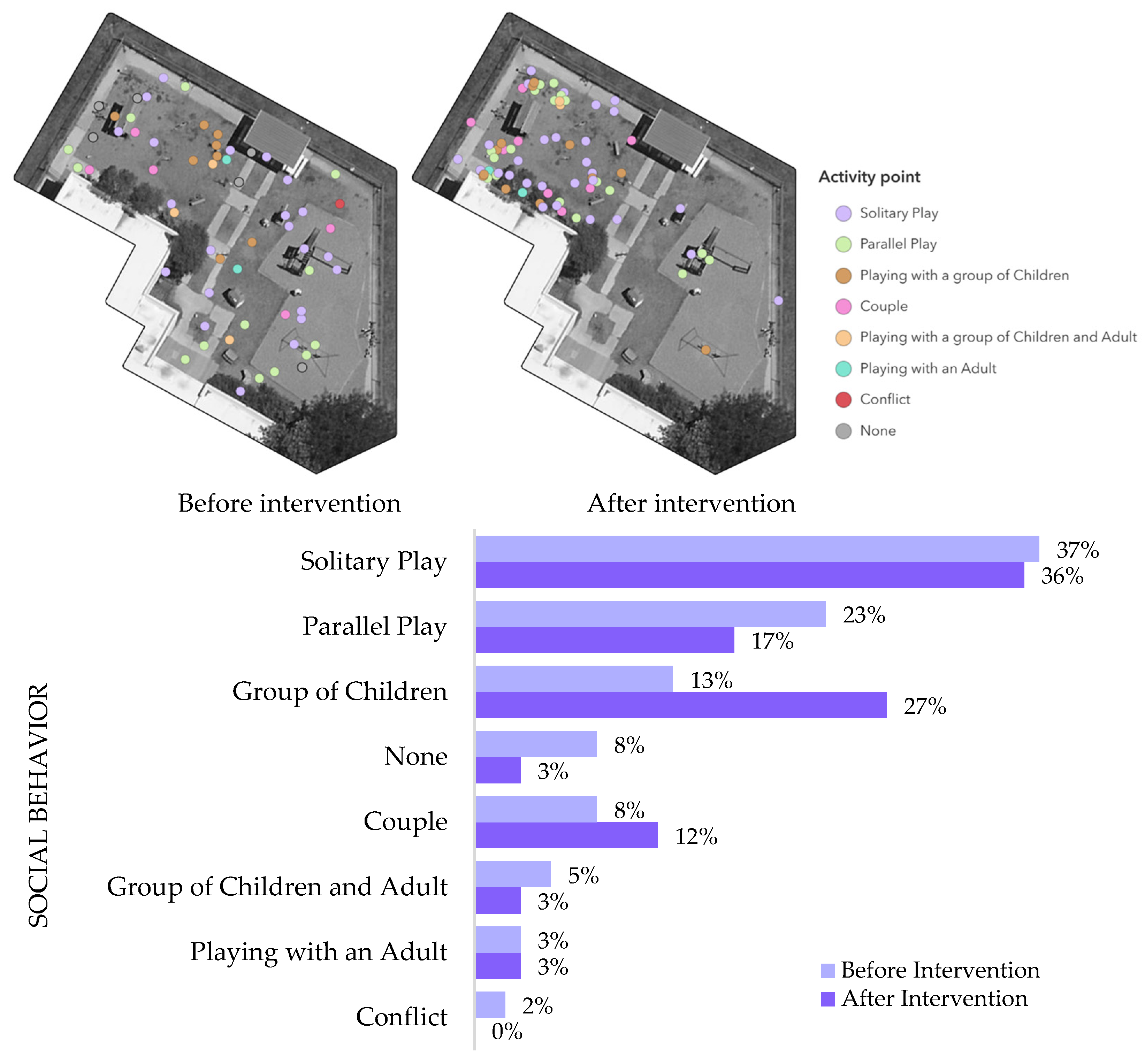

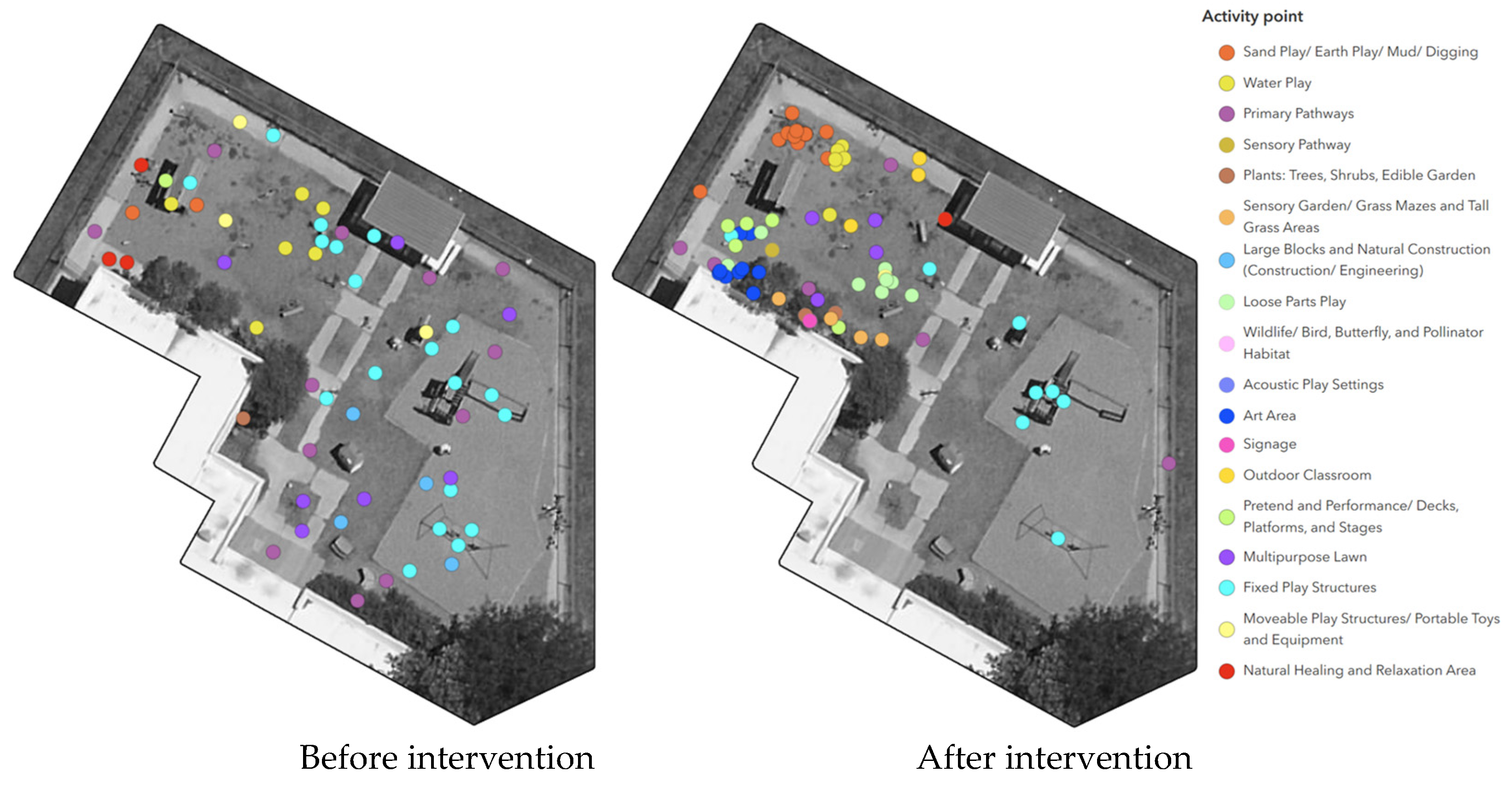

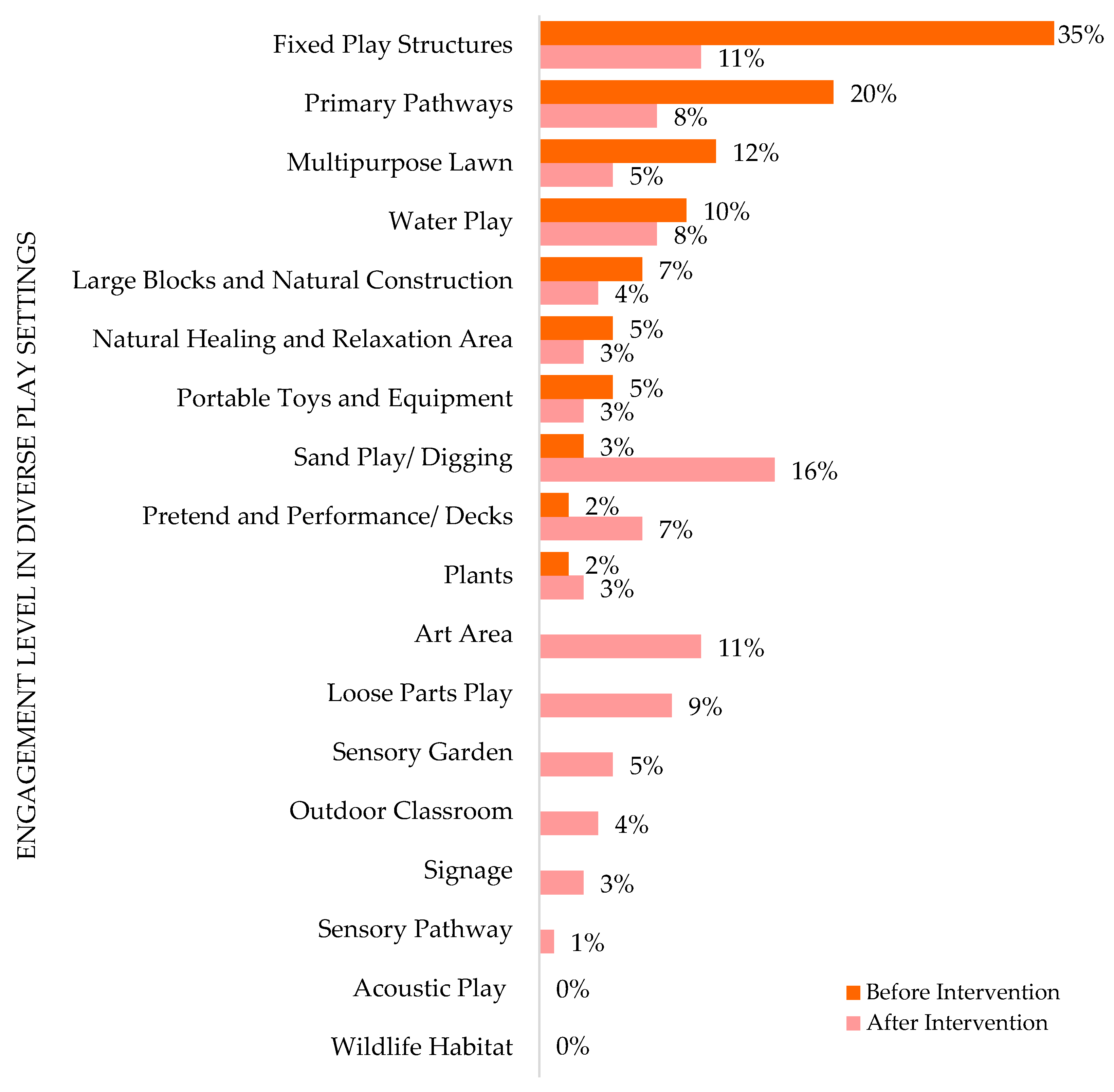

3.1. GIS-Based E-B Mapping Data Comparison (Before and After Intervention Data)

3.2. Video Data Analysis

4. Discussion and Limitations

5. Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bartolini, V. C. (2021). Creating a reggio-inspired stem environment for young children. Redleaf Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R. D., & Corry, R. C. (2011). Evidence-based landscape architecture: The maturing of a profession. Landscape and Urban Planning, 100(4), 327–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, V., Brown, R. D., Schlembach, S., & Kochanowski, L. (2017). Nature by design: Playscape affordances support the use of executive function in preschoolers. Children, Youth and Environments, 27(2), 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. (2015). Benefits of nature contact for children. Journal of Planning Literature, 30(4), 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M. (2022). Is the U.S. falling behind in stem education? Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/us-falling-behind-stem-education-codewizardshq (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Cosco, N. G., Moore, R. C., & Islam, M. Z. (2010). Behavior mapping: A method for linking preschool physical activity and outdoor design. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42(3), 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J. (2004). Mud pies and daisy chains. Every Child, 10(4), 4–5. [Google Scholar]

- Diningrat, S. (2019). Design framework for a school playground. Jurnal Obsesi: Jurnal Pendidikan Anak Usia Dini, 3(2), 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirnagl, U., & Müller, J. (2016). Ich glaub, mich trifft der schlag. In Warum das Gehirn tut, was es tun soll, oder manchmal auch nicht. Droemer. [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, R., Speldewinde, C., & Bridle, H. (2025). Engineering habits of mind in preschool children at scottish forest nurseries and australian bush kinders. British Educational Research Journal, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drown, K. K. C. (2014). Dramatic play affordances of natural and manufactured outdoor settings for preschool-aged children. Utah State University. [Google Scholar]

- Drozd, A. L., Smith, R. L., Kostelec, D. J., Smith, M. F., Colmey, C., Kelahan, G., Group, M., Drozd, E. M., & Bertrand, J. (2017, March 11). Rebuilding smart and diverse communities of interest through steam immersion learning. 2017 IEEE Integrated STEM Education Conference (ISEC), Princeton, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ernst, J. (2014). Early childhood educators’ preferences and perceptions regarding outdoor settings as learning environments. International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education, 2(1), 97–125. [Google Scholar]

- Fiala, A. L. (2017). Nurture through nature: A comparative study between standard and nature-based play in outdoor preschool environments [Master’s thesis, Kansas State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Fisman, L. (2001). Child’s play: An empirical study of the relationship between the physical form of schoolyards and children’s behavior [Unpublished Master’s thesis, Yale University]. [Google Scholar]

- Fjørtoft, I., & Sageie, J. (2000). The natural environment as a playground for children: Landscape description and analyses of a natural playscape. Landscape and Urban Planning, 48(1–2), 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, J. L., Wortham, S. C., & Reifel, R. S. (2012). Play and child development. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. J. (1977). The theory of affordances (Vol. 1, pp. 67–82). Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. J. (2014). The ecological approach to visual perception: Classic edition. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gramkow, M. C., Sidenius, U., Zhang, G., & Stigsdotter, U. K. (2021). From evidence to design solution—On how to handle evidence in the design process of sustainable, accessible and health-promoting landscapes. Sustainability, 13(6), 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurholt, K. P., & Sanderud, J. R. (2016). Curious play: Children’s exploration of nature. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 16(4), 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, S., & Lesmeister, C. (2006). The design of landscapes at child-care centres: Seven cs. Landscape Research, 31(1), 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, S., & Studtmann, K. (1998). Landscape interventions: New directions for the design of children’s outdoor play environments. Landscape and Urban Planning, 42(2), 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter-Doniger, T. (2021). Early childhood steam education: The joy of creativity, autonomy, and play. Art Education, 74(4), 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussim, H., Rosli, R., Nor, N. A. Z. M., Maat, S. M., Mahmud, M. S., Iksan, Z., Rambely, A. S., Mahmud, S. N., Halim, L., Osman, K., & Lay, A. N. (2024). A systematic literature review of informal stem learning. European Journal of STEM Education, 9(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansson, M. (2010). Attractive playgrounds: Some factors affecting user interest and visiting patterns. Landscape Research, 35(1), 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucker, R., & von Au, J. (2022). Outdoor learning—Why it should be high up on the agenda of every educator: Introduction. In High-quality outdoor learning: Evidence-based education outside the classroom for children, teachers and society (pp. 1–26). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, T. J., & Tunnicliffe, S. D. (2022). Introduction: The role of play and stem in the early years. In Play and stem education in the early years: International policies and practices (pp. 3–37). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kernan, M. (2010). Outdoor affordances in early childhood education and care settings: Adults’ and children’s perspectives. Children, Youth and Environments, 20(1), 152–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konkus, Ö. C., & Topsakal, Ü. U. (2022). The effects of steam-based activities on gifted students’ steam attitudes, cooperative working skills and career choices. Journal of Science Learning, 5(3), 398–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostelnik, M. J., Soderman, A. K., Whiren, A. P., & Rupiper, M. (2011). Developmentally appropriate curriculum: Best practices in early childhood education. Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Larrea, I., Muela, A., Miranda, N., & Barandiaran, A. (2019). Children’s social play and affordance availability in preschool outdoor environments. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 27(2), 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malone, K., & Tranter, P. (2003). Children’s environmental learning and the use, design and management of schoolgrounds. Children, Youth and Environments, 13(2), 87–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, D., Friede, C., & Molitor, H. (2020). Nature experience areas: Rediscovering the potential of nature for children’s development. In Research handbook on childhoodnature: Assemblages of childhood and nature research (pp. 1469–1499). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Marušič, B. G., & Marusic, D. (2012). Behavioural maps and gis in place evaluation and design. In Application of geographic information systems. IntechOpen. [Google Scholar]

- Melhuish, E. C. (2016). Provision of quality early childcare services: Synthesis report. European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D. (2010). This never would have happened indoors: Supporting preschool-age children’s learning in a nature explore classroom in minnesota. Dimensions Educational Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Monsur, M. (2024). Built environment and physical activity: Online gis technology for mapping environment-behavior relationships. In Spatial literacy in public health: Faculty-librarian teaching collaborations. Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL). [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R. C. (1989). Playgrounds at the crossroads: Policy and action research needed to ensure a viable future for public playgrounds in the united states. In Public places and spaces (pp. 83–120). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R. C., & Cooper, A. (2014). Nature play & learning places: Creating and managing places where children engage with nature. Natural Learing Initiative. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, R. C., & Wong, H. H. (1997). Natural learning: The life of an environmental schoolyard. Creating environments for rediscovering nature’s way of teaching. ERIC. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, B. J., Owens, W., Ellenbogen, K., Erduran, S., & Dunlosky, J. (2019). Measuring informal stem learning supports across contexts and time. International Journal of STEM Education, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, A.-M., Scott, C., & Wishart, L. (2015). Infant and toddler responses to a redesign of their childcare outdoor play space. Children Youth and Environments, 25(1), 29–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, M., Roshayanti, F., & Sugiyanti, S. (2019). Implementation of steam (science technology engineering art mathematics)-based early childhood education learning in semarang city. CERIA (Cerdas Energik Responsif Inovatif Adaptif), 2(5), 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedovic, S., & Morrissey, A.-M. (2013). Calm active and focused: Children’s responses to an organic outdoor learning environment. Learning Environments Research, 16, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S. (1971). How not to cheat children, the theory of loose parts. Landscape Architecture, 62(1), 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Nugraha, D. M. D. P., Juniayanti, D., & Dewi, N. W. P. (2025, February 19). Enhancing critical thinking skills of fifth grade students through steam education in lesson study activities. International Conference on Social Science, Environment and Technology Development, Bali, Indonesia. [Google Scholar]

- Oltman, M. (2002). Natural wonders: A guide to early childhood for environmental educators. ERIC. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, W. (2024). The outdoor classroom: Integrating the outdoors into the classroom [Master’s thesis, California State University]. [Google Scholar]

- Refshauge, A. D., Stigsdotter, U. K., Lamm, B., & Thorleifsdottir, K. (2015). Evidence-based playground design: Lessons learned from theory to practice. Landscape Research, 40(2), 226–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivkin, M. S., & Schein, D. L. (2014). The great outdoors: Advocating for natural spaces for young children. National Association for the Education of Young Children. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, J. (2016). The memory illusion: Remembering, forgetting, and the science of false memory. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel, D. (2004). Place-based education: Connecting classrooms and communities. Education for Meaning and Social Justice, 17(3), 63–64. [Google Scholar]

- Speldewinde, C., & Campbell, C. (2023). ‘Bush kinders’: Developing early years learners technology and engineering understandings. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 33(3), 775–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stichler, J. F., & Hamilton, D. K. (2008). Evidence-based design: What is it? HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 1(2), 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Trina, N. A., Monsur, M., Cosco, N., Shine, S., Loon, L., & Mastergeorge, A. (2024). How do nature-based outdoor learning environments affect preschoolers’ steam concept formation? A scoping review. Education Sciences, 14(6), 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, T. (2006). Preschool science environment: What is available in a preschool classroom? Early Childhood Education Journal, 33, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunnicliffe, S. D., & Kennedy, T. J. (2022). Play and stem education in the early years: International policies and practices. Springer Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Wahyuningsih, S., Nurjanah, N. E., Rasmani, U. E. E., Hafidah, R., Pudyaningtyas, A. R., & Syamsuddin, M. M. (2020). Steam learning in early childhood education: A literature review. International Journal of Pedagogy and Teacher Education, 4(1), 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiser, L. E. (2022). Young children’s free play in nature: An essential foundation for stem learning in germany. In Play and stem education in the early years: International policies and practices (pp. 85–103). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wised, S., & Inthanon, W. (2024). The evolution of steam-based programs: Fostering critical thinking, collaboration, and real-world application. Journal of Education and Learning Reviews, 1(4), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worch, E., Odell, M., & Magdich, M. (2022). Engaging children in science learning through outdoor play. In Play and stem education in the early years: International policies and practices (pp. 105–122). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Worch, E. A., & Haney, J. J. (2011). Assessing a children’s zoo designed to promote science learning behavior through active play: How does it measure up? Children, Youth and Environments, 21(2), 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worth, K., & Grollman, S. (2003). Worms, shadows and whirlpools: Science in the early childhood classroom. ERIC. [Google Scholar]

- Yıldırım, G., & Akamca, G. Ö. (2017). The effect of outdoor learning activities on the development of preschool children. South African Journal of Education, 37(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, J., Stolterman, E., & Forlizzi, J. (2010, August 16–20). An analysis and critique of research through design: Towards a formalization of a research approach. 8th ACM Conference on Designing Interactive Systems, Aarhus, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

| Reviewed Studies | STEAM Behaviors | Supportive Settings/Landscape Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Children have numerous opportunities to engage in science activities in their everyday outdoor environment. Activities like gathering pinecones, observing a spider’s web, or watching fish move can spark their interest in science. Such experiences cater to children’s inherent curiosity and encourage them to explore further (Tu, 2006). | Observing Exploring Counting | Loose Parts Play Wildlife Habitat |

| The outdoor environment provides volitional learning opportunities that allow children to manipulate elements of the outdoor setting. Places to dig, watery places, and sandy areas where loose parts provide tools for children’s imagination and increase their ability to mold, shape, shift, press, and drizzle (Herrington & Lesmeister, 2006). | Observing Exploring Hypothesis/Cause and Effect Building Measuring Making an Art | Sand Play Digging Water Play Loose Parts Play |

| Children develop eye–hand coordination while pouring, scouring, gripping, and squeezing activities and strengthen tiny muscles when digging, ladling, carrying, and organizing materials. Because children learn about measuring, comparison, observation, and sharing objects, their cognitive, social, and language skills improve (Kostelnik et al., 2011). | Observing Exploring Measuring Comparing Sorting Asking Questions | Garden Sand Play Water Play Loose Parts Play Digging |

| While children were busy running, climbing, and splashing, they were often engaged in exploratory science learning by interacting with their environment, making inquiries, or carrying out plans (E. A. Worch & Haney, 2011). | Observing Exploring Hypothesis/Cause and Effect Asking Questions | Multipurpose Lawn Fixed Play Structure Water Play |

| Fjørtoft and Sageie (2000) identified that various landscape features, including the type and density of vegetation, the slope, and the roughness of the terrain, significantly influence children’s play activities. Children were found to choose play areas based on these landscape characteristics. Additionally, changes in the landscape with the seasons were observed to affect children’s seasonal play preferences, indicating a dynamic interaction between the natural environment and play behavior (Ernst, 2014). | Observing Exploring Hypothesis/Cause and Effect Asking Questions Comparing. | Plants Garden Topography and Landforms |

| A large grassy area where children can run freely; a number of areas with each supporting a different kind of play activity; pathways to explore that are surrounded by interesting vegetation and stepping stones through garden areas; a constantly changing supply of materials and flexible play equipment with an emphasis on natural or recycled items and loose, moveable elements that children can manipulate; plants of differing heights used in creative ways; garden areas for children to grow and collect food; areas for digging; diverse and natural ground surfaces; and special features such as trickle streams or butterfly houses. In essence, play spaces containing elements such as these have the potential to become “a sea of natural sensory stimuli for children” (Davis, 2004). | Observing Exploring Hypothesis/Cause and Effect Asking questions Building Sorting Measuring Comparing Counting Language and Literacy | Multipurpose Lawn Primary Pathway Sensory Pathway Sensory Garden Flexible Play Equipment Loose Parts Play Sand Play Wildlife Habitat |

| Some inquiry-based or project-based learning examples include planting and tending a garden, cooking with vegetables and fruits, composting with worms, and observing and recording the life cycles of plants and animals (Bartolini, 2021). | Observing Exploring Hypothesis/Cause and Effect Asking questions Measuring Comparing Language and Literacy | Plants Sensory Garden Wildlife Habitat |

| Creating small, intimate, and “private” spaces conveys Anchorage Park Kindergarten’s belief in children’s competencies to imagine, reflect, wonder, and communicate while relaxing alone or with others. Designing with interesting fabrics and patterns, sheer drapery, wind chimes, and books creates an inviting time and space for curious minds to ponder (Bartolini, 2021). | Observing Exploring Asking Questions Building Making Art Music Language and Literacy | Acoustic Play Settings Outdoor Reading and Language Play Natural Healing and Relaxation Area |

| Signs can be an important element of pathway settings. They support a feeling of exploration and discovery by providing cues and information to enhance the learning process (Moore & Cooper, 2014) | Observing Exploring Asking questions Comparing Language and Literacy Signs | Primary Pathways Signage |

| Plants provide loose parts and play props, including leaves, flowers, fruit, nuts, seeds, and small sticks. Together with soil, sand, and water, manipulative settings can be designed and managed to extend the play and learning affordances of static, fixed structures (Moore & Cooper, 2014). | Diverse Affordances | Sand Play Digging Water Play Loose Parts Play |

| Play Behavior |

| 1. Functional/Physical Play, 2. Constructive Play, 3. Dramatic Play, 4. Game with Rules, 5. No Play |

| Social Behavior |

| 1. Solitary Play, 2. Parallel Play, 3. Couple, 4. Playing with a Group of Children 5. Playing with an Adult, 6. Conflict, 7. Playing with a Group of Children and Adult 8. None |

| Conversation |

| 1. Self, 2. One Child, 3. Multiple Child, 4. One Adult, 5. Child + Adult, 6. Multiple Adults, 7. No Conversation |

| STEAM Learning Behavior |

| Science+ Technology + Engineering: 1. Observing, 2. Exploring, 3. Describing/Prescribing/Predicting/Concluding, 4. Hypothesis/Cause and Effect/Experiments, 5. Asking Questions, 6. Building, 7. Manipulating |

|

Math: 1. Sorting/Classifying, 2. Measuring, 3. Comparing, 4. Counting, 5. Balancing |

|

Arts: 1. Art, 2. Music, 3. Dance, 4. Language and Literacy, 5. Signs |

| Play Settings/Behavior Location |

| 1. Sand Play/Earth Play/Mud/Digging; 2. Water Play; 3. Primary Pathways; 4. Sensory Pathway; 5. Plants: Trees, Shrubs, Edible Garden; 6. Sensory Garden/Grass Mazes and Tall Grass Areas; 7. Large Blocks and Natural Construction (Construction/Engineering); 8. Loose Parts Play; 9. Wildlife/Bird, Butterfly, and Pollinator Habitat; 10. Acoustic Play Settings; 11. Art Area; 12. Signage: Directional, Informational, Identification, Regulatory, and Inspirational Signs; 13. Outdoor Classroom; 14. Pretend and Performance/Decks, Platforms, and Stages; 15. Multipurpose Lawn; 16. Fixed Play Structures; 17. Moveable Play Structures/Portable Toys and Equipment; 18. Natural Healing and Relaxation Area. |

| Aspect | E-B Mapping Data | Video Data |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Tracks where and how often children engage in observable STEAM behaviors across predefined zones. | Explores how and why behaviors occur by capturing temporal sequences and contextual interactions. |

| Data Type | Quantitative: frequency counts are displayed through GIS mapping. | Qualitative: coded narrative sequences with social interaction data. |

| Behavioral Insight | Captures broad behavior patterns (e.g., building, sorting), indicating engagement trends with specific settings or landscape materials. | Reveals internal thinking processes, intentions, and problem-solving steps during behaviors like constructing or experimenting. |

| Affordance Recognition | Identifies zones offering strong affordances based on higher activity density (e.g., sensory gardens, loose parts zones). | Explores how children interpret and transform affordances into learning opportunities through imaginative or exploratory play. |

| Temporal Analysis | Provides interval-based snapshots across sessions but lacks continuous behavioral context. | Offers continuous behavior tracking, showing sequences like trial and error, reflection, or adaptive use of materials. |

| Spatial Insight | Precisely maps where behaviors occur and which areas are under or over-utilized after the intervention. | Mapping capability is limited, but it effectively reveals what occurred within captured spaces and how different activities are interrelated. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Trina, N.A.; Monsur, M.; Cosco, N.; Loon, L.; Shine, S.; Mastergeorge, A. Rethinking Traditional Playgrounds: Temporary Landscape Interventions to Advance Informal Early STEAM Learning in Outdoors. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 952. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080952

Trina NA, Monsur M, Cosco N, Loon L, Shine S, Mastergeorge A. Rethinking Traditional Playgrounds: Temporary Landscape Interventions to Advance Informal Early STEAM Learning in Outdoors. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):952. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080952

Chicago/Turabian StyleTrina, Nazia Afrin, Muntazar Monsur, Nilda Cosco, Leehu Loon, Stephanie Shine, and Ann Mastergeorge. 2025. "Rethinking Traditional Playgrounds: Temporary Landscape Interventions to Advance Informal Early STEAM Learning in Outdoors" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 952. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080952

APA StyleTrina, N. A., Monsur, M., Cosco, N., Loon, L., Shine, S., & Mastergeorge, A. (2025). Rethinking Traditional Playgrounds: Temporary Landscape Interventions to Advance Informal Early STEAM Learning in Outdoors. Education Sciences, 15(8), 952. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080952