Student-Centered Curriculum: The Innovative, Integrative, and Comprehensive Model of “George Emil Palade” University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences, and Technology of Targu Mures

Abstract

1. Introduction

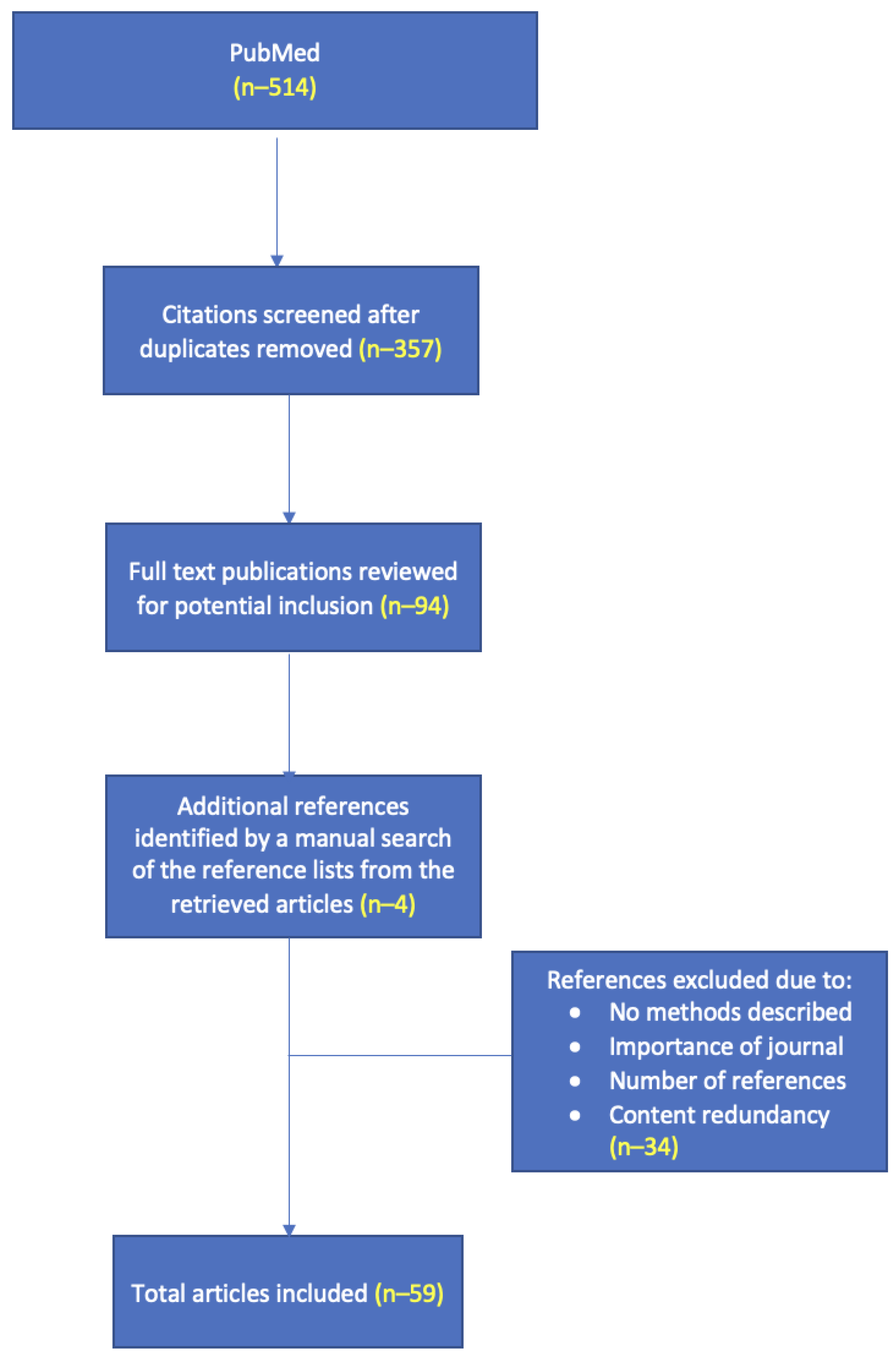

2. Literature Search

3. Medical Innovation in Romania

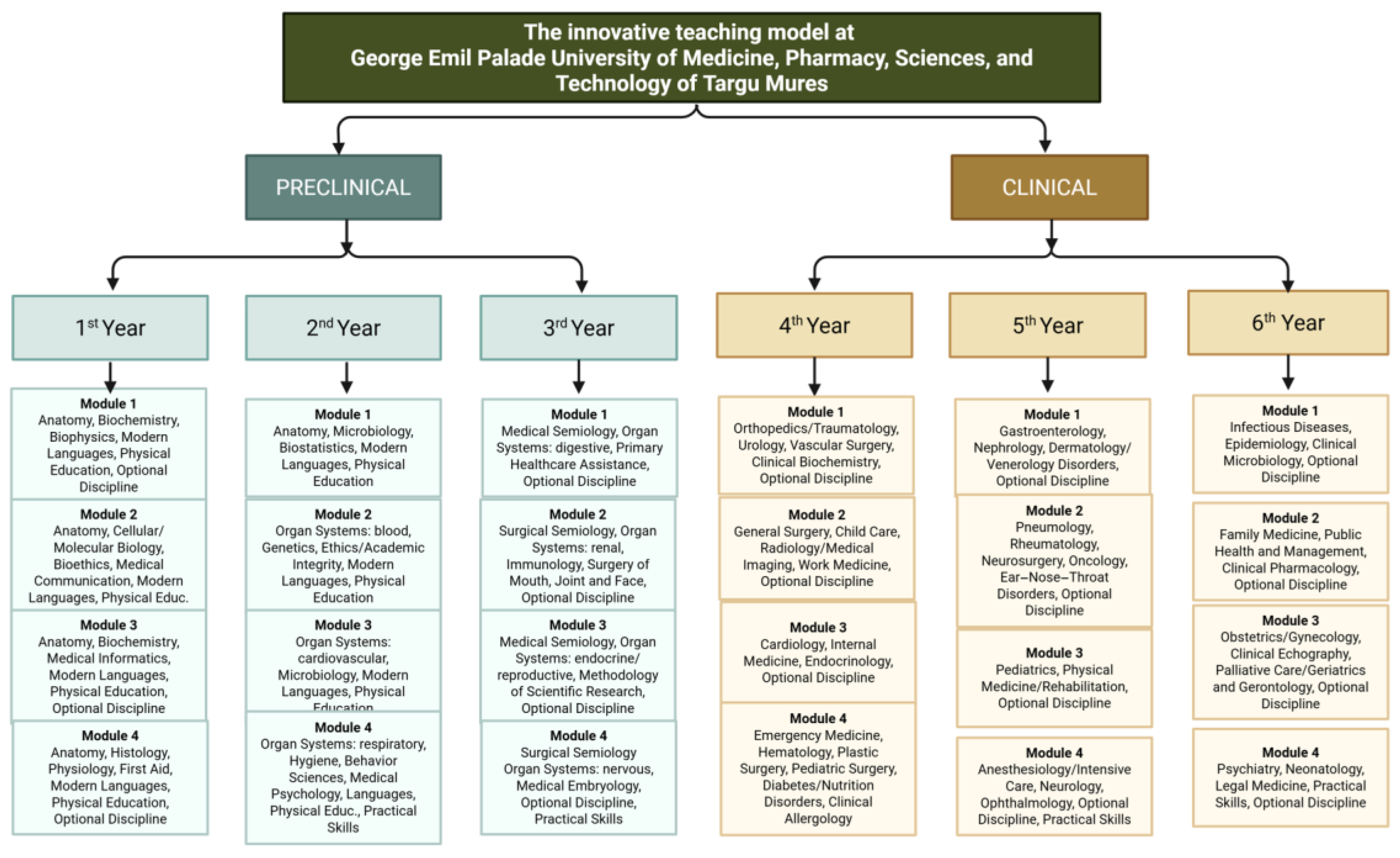

3.1. The Teaching Model

3.2. The Assessment of Theoretical Knowledge

3.3. The Assessment of Clinical Competencies

4. Concepts of Medical Education Worldwide

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aagaard, E., Teherani, A., & Irby, D. M. (2004). Effectiveness of the one-minute preceptor model for diagnosing the patient and the learner: Proof of concept. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 79(1), 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abuzied, A. I. H., & Nabag, W. O. M. (2023). Structured viva validity, reliability, and acceptability as an assessment tool in health professions education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, A., Batra, B., Sood, A., Ramakantan, R., Bhargava, S. K., Chidambaranathan, N., & Indrajit, I. (2010). Objective structured clinical examination in radiology. The Indian Journal of Radiology & Imaging, 20(2), 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S., Saleem, S. G., Khatri, A., & Mukhtar, S. (2023). ‘To teach or not to teach-that is the question’ The educational and clinical impact of introducing an outcome based, modular curriculum in Social Emergency Medicine (SEM) at a private tertiary care center in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Therwah, R., Heshmat, M., El-Sharief, M., & Hassab-Allah, I. (2025). Simulation modeling of student enrolment to solve operations problems: A case of the Saad Al-Abdullah Academy in Kuwait. Alexandria Engineering Journal, 119, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, Z., Seng, C., & Eng, K. (2006). Practical guide to medical student assessment. World Scientific Book. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, D., Lahner, F.-M., Huwendiek, S., Schmitz, F. M., & Guttormsen, S. (2020). An overview of and approach to selecting appropriate patient representations in teaching and summative assessment in medical education. Swiss Medical Weekly, 150, w20382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben-Menachem, E., Ezri, T., Ziv, A., Sidi, A., Brill, S., & Berkenstadt, H. (2011). Objective structured clinical examination-based assessment of regional anesthesia skills: The Israeli national board examination in Anesthesiology experience. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 112(1), 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkenstadt, H., Ben-Menachem, E., Dach, R., Ezri, T., Ziv, A., Rubin, O., & Keidan, I. (2012). Deficits in the provision of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during simulated obstetric crises: Results from the Israeli Board of Anesthesiologists. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 115(5), 1122–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boulet, J. R. (2008). Summative assessment in medicine: The promise of simulation for high-stakes evaluation. Academic Emergency Medicine: Official Journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine, 15(11), 1017–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins, S., Johnson, N., & Light, G. (2012). Changing conceptions of teaching in medical faculty. Medical Teacher, 34(11), 902–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carraccio, C., Englander, R., Van Melle, E., Ten Cate, O., Lockyer, J., Chan, M.-K., Frank, J. R., Snell, L. S., & International Competency-Based Medical Education Collaborators. (2016). Advancing competency-based medical education: A charter for clinician-educators. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 91(5), 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, M., & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP framework: Linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 49(4), 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chipman, J. G., Beilman, G. J., Schmitz, C. C., & Seatter, S. C. (2007). Development and pilot testing of an OSCE for difficult conversations in surgical intensive care. Journal of Surgical Education, 64(2), 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, M., & Loudon, K. (2011). Effects on patients of their healthcare practitioner’s or institution’s participation in clinical trials: A systematic review. Trials, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, R., Murnaghan, L., Collins, J., & Pratt, D. (2005). An update on master’s degrees in medical education. Medical Teacher, 27(8), 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrie, K., Wiles, M., Flack, J., & Lamb, J. (2011). A novel objective structured clinical examination for the assessment of transfusion practice in anaesthesia. The Clinical Teacher, 8(2), 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlin, P. A., & Featherstone, C. R. (2017). How to write a high quality multiple choice question (MCQ): A guide for clinicians. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery: The Official Journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery, 54(5), 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dent, J., Harden, R., & Hunt, D. (2017). A practical guide for medical teachers. Amsterdam (5th ed.). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Derish, P. A., & Annesley, T. M. (2011). How to write a rave review. Clinical Chemistry, 57(3), 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du Bois, A., Rochon, J., Lamparter, C., Pfisterer, J., & AGO Organkommission OVAR PFisterer. (2005). Pattern of care and impact of participation in clinical studies on the outcome in ovarian cancer. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer: Official Journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society, 15(2), 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, S., Jha, V., & Kaufmann, S. (2004). The Yorkshire Modular Training Programme: A model for structured training and quality assurance in obstetrics and gynaecology. Medical Teacher, 26(6), 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertl-Wagner, B., Barkhausen, J., Mahnken, A. H., Mentzel, H. J., Uder, M., Weidemann, J., Stumpp, P., German Association of Chairmen in Academic Radiology (KLR) & German Roentgen Society (DRG). (2016). White paper: Radiological curriculum for undergraduate medical education in Germany. RoFo: Fortschritte Auf Dem Gebiete Der Rontgenstrahlen Und Der Nuklearmedizin, 188(11), 1017–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farmad, S. A., Esfidani, A., & Shahbazi, S. (2023). A comparative study of the curriculum in master degree of medical education in Iran and some selected countries. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, J. R., Mungroo, R., Ahmad, Y., Wang, M., De Rossi, S., & Horsley, T. (2010). Toward a definition of competency-based education in medicine: A systematic review of published definitions. Medical Teacher, 32(8), 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehlhar, K. (2019). The model medical degree programme ‘human medicine’ in Oldenburg—The European medical school Oldenburg-Groningen. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 36(5), Doc51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- “George Emil Palade” University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science, and Technology of Targu Mures. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.scimagoir.com/institution.php?idp=11897 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Grijpma, J. W., Mak-van der Vossen, M., Kusurkar, R. A., Meeter, M., & de la Croix, A. (2022). Medical student engagement in small-group active learning: A stimulated recall study. Medical Education, 56(4), 432–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, V., Williams, E. R., & Wadhwa, R. (2021). Multiple-choice tests: A-Z in best writing practices. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 44(2), 249–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guse, A. H., & Kuhlmey, A. (2018). Model study programs in medicine: Innovations in medical education in Hamburg and Berlin. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz, 61(2), 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harden, R. M. (2014). Progression in competency-based education. Medical Education, 48(8), 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastie, M. J., Spellman, J. L., Pagano, P. P., Hastie, J., & Egan, B. J. (2014). Designing and implementing the objective structured clinical examination in anesthesiology. Anesthesiology, 120(1), 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Härtl, A., Berberat, P., Fischer, M. R., Forst, H., Grützner, S., Händl, T., Joachimski, F., Linné, R., Märkl, B., Naumann, M., Putz, R., Schneider, W., Schöler, C., Wehler, M., & Hoffmann, R. (2017). Development of the competency-based medical curriculum for the new Augsburg University Medical School. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 34(2), Doc21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitzblech, T., Maaz, A., Rollinger, T., Ludwig, S., Dettmer, S., Wurl, W., Roa-Romero, Y., Raspe, R., Petzold, M., Breckwoldt, J., & Peters, H. (2019). The modular curriculum of medicine at the Charité Berlin—A project report based on an across-semester student evaluation. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 36(5), Doc54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinpour, M., & Samii, H. (2001). Assessment of medical interns opinion about education in surgery courses in Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Iranian Journal of Medical Education, 1(3), 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P.-H., Haywood, M., O’Sullivan, A., & Shulruf, B. (2019). A meta-analysis for comparing effective teaching in clinical education. Medical Teacher, 41(10), 1129–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-S., Liu, M., Huang, C.-H., & Liu, K.-M. (2007). Implementation of an OSCE at Kaohsiung Medical University. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 23(4), 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwanaga, J., Loukas, M., Dumont, A. S., & Tubbs, R. S. (2021). A review of anatomy education during and after the COVID-19 pandemic: Revisiting traditional and modern methods to achieve future innovation. Clinical Anatomy, 34(1), 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahani, M.-A., Ghanavatizadeh, A., Delavari, S., Abbasi, M., Nikbakht, H.-A., Farhadi, Z., Darzi, A., & Mahmoudi, G. (2023). Strengthening E-learning strategies for active learning in crisis situations: A mixed-method study in the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthikeyan, K., & Kumar, A. (2014). Integrated modular teaching in dermatology for undergraduate students: A novel approach. Indian Dermatology Online Journal, 5(3), 266–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G. S. J., Chin, Y. H., Jiang, A. A., Mg, C. H., Nistala, K. R. Y., Iyer, S. G., Lee, S. S., Chong, C. S., & Samarasekera, D. D. (2021). Teaching medical research to medical students: A systematic review. Medical Science Educator, 31(2), 945–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maaz, A., Hitzblech, T., Arends, P., Degel, A., Ludwig, S., Mossakowski, A., Mothes, R., Breckwoldt, J., & Peters, H. (2018). Moving a mountain: Practical insights into mastering a major curriculum reform at a large European medical university. Medical Teacher, 40(5), 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumdar, S. R., Roe, M. T., Peterson, E. D., Chen, A. Y., Gibler, W. B., & Armstrong, P. W. (2008). Better outcomes for patients treated at hospitals that participate in clinical trials. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168(6), 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maker, V. K., & Bonne, S. (2009). Novel hybrid objective structured assessment of technical skills/objective structured clinical examinations in comprehensive perioperative breast care: A three-year analysis of outcomes. Journal of Surgical Education, 66(6), 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malau-Aduli, B. S., Jones, K., Saad, S., & Richmond, C. (2022). Has the OSCE met its final demise? Rebalancing clinical assessment approaches in the peri-pandemic world. Frontiers in Medicine, 9, 825502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mărginean, C. O., Meliţ, L. E., Chinceşan, M., Mureşan, S., Georgescu, A. M., Suciu, N., Pop, A., & Azamfirei, L. (2017). Communication skills in pediatrics—The relationship between pediatrician and child. Medicine, 96(43), e8399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, S. F. (2016). Case-based learning and its application in medical and health-care fields: A review of worldwide literature. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 3, JMECD.S20377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, P. H., Robins, L. S., & Schaad, D. (2005). Creating a curriculum for training health profession faculty leaders. In K. Henriksen, J. B. Battles, E. S. Marks, & D. I. Lewin (Eds.), Advances in patient safety: From research to implementation (Volume 4: Programs, tools, and products). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK20614/ (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Nasr El-Din, W. A., Atwa, H., Potu, B. K., Deifalla, A., & Fadel, R. A. (2023). Checklist-based active learning in anatomy demonstration sessions during the COVID-19 pandemic: Perception of medical students. Morphologie: Bulletin De l’Association Des Anatomistes, 107(357), 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onyura, B., Baker, L., Cameron, B., Friesen, F., & Leslie, K. (2016). Evidence for curricular and instructional design approaches in undergraduate medical education: An umbrella review. Medical Teacher, 38(2), 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overall Rankings 2023—UI GreenMetric. (n.d.). Available online: https://greenmetric.ui.ac.id/rankings/overall-rankings-2023 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Pierre, M., Miklavcic, M., Margulan, M., & Asfura, J. S. (2022). Research education in medical curricula: A global analysis. Medical Science Educator, 32(2), 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reimschisel, T., Herring, A. L., Huang, J., & Minor, T. J. (2017). A systematic review of the published literature on team-based learning in health professions education. Medical Teacher, 39(12), 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rheingans, A., Soulos, A., Mohr, S., Meyer, J., & Guse, A. H. (2019). The Hamburg integrated medical degree program iMED. GMS Journal for Medical Education, 36(5), Doc52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selby, P., & Autier, P. (2011). The impact of the process of clinical research on health service outcomes. Annals of Oncology: Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 22(Suppl. S7), vii5–vii9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singla, R., Pupic, N., Ghaffarizadeh, S.-A., Kim, C., Hu, R., Forster, B. B., & Hacihaliloglu, I. (2024). Developing a Canadian artificial intelligence medical curriculum using a Delphi study. NPJ Digital Medicine, 7(1), 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sloan, D. A., Donnelly, M. B., Schwartz, R. W., & Strodel, W. E. (1995). The objective structured clinical examination. The new gold standard for evaluating postgraduate clinical performance. Annals of Surgery, 222(6), 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, J. (2003). Learning and teaching in the clinical environment. BMJ, 326(7389), 591–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, C. M., Masood, H., Pandian, V., Laeeq, K., Akst, L., Francis, H. W., & Bhatti, N. I. (2010). Development and pilot testing of an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) on hoarseness. The Laryngoscope, 120(11), 2177–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasi, R., Stark, K., & Scheiermann, P. (2020). Efficacy of a certified modular ultrasound curriculum. Der Anaesthesist, 69(3), 192–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torralba, K. D., & Doo, L. (2020). Active learning strategies to improve progression from knowledge to action. Rheumatic Diseases Clinics of North America, 46(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University | Ranking Web of Universities: Webometrics Ranks 30000 Institutions. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/george-emil-palade-university-medicine-pharmacy-science-and-technology (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- VanDruff, V. N., Wong, H. J., Amundson, J. R., Wu, H., Campbell, M., Kuchta, K., Hedberg, H. M., Linn, J., Haggerty, S., Denham, W., & Ujiki, M. B. (2023). ‘Into the fire’ approach to teaching endoscopic foreign body removal using a modular simulation curriculum. Surgical Endoscopy, 37(2), 1412–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vegi, V. A. K., Sudhakar, P. V., Bhimarasetty, D. M., Pamarthi, K., Edara, L., Kutikuppala, L. V. S., Suvvari, T. K., & Anand, S. (2022). Multiple-choice questions in assessment: Perceptions of medical students from low-resource setting. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivekananda-Schmidt, P., & Sandars, J. (2016). Developing and implementing a patient safety curriculum. The Clinical Teacher, 13(2), 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, W., Zou, Y., Ao, Y., Cai, Y., Huang, Z., Li, M., Xu, C., Jia, Y., Yang, Y., Yang, Y., & Lin, H. (2020). Evaluation of integrated modular teaching in Chinese ophthalmology trainee courses. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yannier, N., Hudson, S. E., Koedinger, K. R., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Golinkoff, R. M., Munakata, Y., Doebel, S., Schwartz, D. L., Deslauriers, L., McCarty, L., Callaghan, K., Theobald, E. J., Freeman, S., Cooper, K. M., & Brownell, S. E. (2021). Active learning: ‘Hands-on’ meets ‘minds-on’. Science, 374(6563), 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yew, E., & Goh, K. (2016). Problem-based learning: An overview of its process and impact on learning. Health Professions Education Health Professions Education, 2(2), 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azamfirei, L.; Meliț, L.E.; Mărginean, C.O.; Văsieșiu, A.-M.; Cotoi, O.S.; Bică, C.; Muntean, D.L.; Gurzu, S.; Brînzaniuc, K.; Bănescu, C.; et al. Student-Centered Curriculum: The Innovative, Integrative, and Comprehensive Model of “George Emil Palade” University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences, and Technology of Targu Mures. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080943

Azamfirei L, Meliț LE, Mărginean CO, Văsieșiu A-M, Cotoi OS, Bică C, Muntean DL, Gurzu S, Brînzaniuc K, Bănescu C, et al. Student-Centered Curriculum: The Innovative, Integrative, and Comprehensive Model of “George Emil Palade” University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences, and Technology of Targu Mures. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):943. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080943

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzamfirei, Leonard, Lorena Elena Meliț, Cristina Oana Mărginean, Anca-Meda Văsieșiu, Ovidiu Simion Cotoi, Cristina Bică, Daniela Lucia Muntean, Simona Gurzu, Klara Brînzaniuc, Claudia Bănescu, and et al. 2025. "Student-Centered Curriculum: The Innovative, Integrative, and Comprehensive Model of “George Emil Palade” University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences, and Technology of Targu Mures" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080943

APA StyleAzamfirei, L., Meliț, L. E., Mărginean, C. O., Văsieșiu, A.-M., Cotoi, O. S., Bică, C., Muntean, D. L., Gurzu, S., Brînzaniuc, K., Bănescu, C., Slevin, M., Varga, A., & Muresan, S. (2025). Student-Centered Curriculum: The Innovative, Integrative, and Comprehensive Model of “George Emil Palade” University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences, and Technology of Targu Mures. Education Sciences, 15(8), 943. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15080943