Abstract

In the U.S. public school system, White middle-class female teacher workforces have dominantly served an increasing number of students of color. While the racial interplay between teachers and students has offered insightful implications for continuing disparities in student discipline, little research has been done to link the racial match of the teaching force to their served communities. This study examines how the ethnoracial congruence between teachers and populations in their school district moderates racial gaps in in-school suspension rates between White and non-White students in Tennessee. The research demonstrates that when teachers serve communities of the same race, their schools are less likely to show a substantial gap in in-school suspensions between White students and students of color.

1. Introduction

Racial disparities in various domains, such as salary and access to health services, are not new. In addition to persistent racial and ethnic gaps in test scores, a growing ethnoracial imbalance in student discipline has been reported from the early childhood level onward, reinforcing the school-to-prison pipeline (Gerlinger et al., 2021; Zinsser et al., 2022). Current research on student discipline has underscored the critical role of teachers as street-level bureaucrats in school settings. As the individuals who observe student behavior, make initial decisions on referrals, and intervene in resolution procedures, teachers play a pivotal role in either perpetuating or mitigating racial disproportionalities in school discipline (Muñiz, 2021; Owens, 2022; S. Wang et al., 2023). Because office referrals and in-school suspensions rely heavily on classroom teachers’ judgments of student misbehavior (Okonofua et al., 2016; Smolkowski et al., 2016), teacher–student interactions and teacher biases are expected to account for the overuse of exclusionary discipline practices for students from specific demographic and socioeconomic groups (Shirrell et al., 2024; Wymer et al., 2022). In the U.S. public school system, where nearly 80% of the teacher workforce comprises non-Hispanic White females and serves a growing number of students of color (National Center for Education Statistics, 2020), teachers’ understanding of their students’ diverse backgrounds has significantly shaped how they interact with and respond to those students (Larson et al., 2018). While the ethnoracial dynamics between teachers and students have offered important insights into persistent disparities in student discipline, relatively little research has been conducted to link the demographic composition of the teaching workforce to the communities they serve (Park & Favero, 2023; Riddle & Sinclair, 2019). Given the low mobility in geographically fragmented teacher labor markets, the degree of ethnoracial congruence between teachers and their served communities holds promise for explaining ethnoracial disproportionalities in school discipline. As the ethnoracial interplay between teachers and their served communities can offer insightful implications for continuing disparities in student discipline, this study examines how the ethnoracial match between teachers and the overall community populations in their school districts is related to ethnoracial disparities in in-school suspension rates between White and non-White students in Tennessee.

2. Literature

2.1. Disproportionality in School Discipline

With the rise of high-stakes testing and the increasing frequency of mass shootings on school grounds, school suspension rates and the implementation of zero-tolerance policies have increased across the American public school system (Diliberti et al., 2019). Approximately half of U.S. public schools have school resource officers regularly stationed on campus, and law enforcement officers carrying a firearm are more likely to be present at large schools (Curran et al., 2019). Schools in urban school districts report more frequent incidents of both violent and non-violent behaviors, and secondary school students are more likely to be punished for disruptive behaviors than primary school children (Diliberti et al., 2019; K. Wang et al., 2020). In addition to the expansion of exclusionary discipline practices from pre-kindergarten through high school, substantial evidence on school safety and student discipline has indicated significant racial and ethnic disparities in punitive school discipline. African American students are referred to the office more frequently than their peers, often resulting in exclusion from instructional activities, while Asian students are suspended less often than African American and Hispanic or Latine/x students (Nguyen et al., 2019; Wilkerson & Afacan, 2022). Students from low-income families or single-parent households and male students have been victimized by exclusionary discipline with a high prevalence (Barrett et al., 2021).

Students’ demographic and socioeconomic characteristics are not primary determinants or predictors of misconduct, however (Welsh & Little, 2018). Persistent disparities in school discipline by race and ethnicity have drawn attention to broader contextual influences beyond their individual traits and family background. Racial and ethnic disparities in school discipline are shaped in part by increasing community support for school resource officers and the growing presence of law enforcement in schools (Gottfredson et al., 2020; Riddle & Sinclair, 2019). As well as the availability of green spaces in communities (Lee & Movassaghi, 2021; Raney et al., 2019), unhealthy social networks and marginalized neighborhood conditions have also been shown to contribute to student misconduct and, subsequently, discipline gaps (Brazil, 2016; Burdick-Will, 2017). Although research on school segregation has demonstrated inconsistent patterns in ethnoracial disparities in school discipline (Lee, 2023; Mawene & Bal, 2020), communities that are less engaged in efforts to integrate schools tend to suspend African American students at higher rates (Capers, 2019; Kupchik & Henry, 2023). These findings suggest that ethnoracial disparities in student suspension and expulsion may stem more from structural racism and institutional constraints than from students’ individual behavior (Billings & Hoekstra, 2023).

Current research on ethnoracial disproportionalities in exclusionary school actions has sought to understand why and how certain student groups are more likely to be referred, suspended, or expelled. Studies have presented that students of color are more often referred for less severe and more subjective infractions—such as noise and disrespect—rather than for more objective and clearly defined behavior like drug use, smoking, or vandalism (Annamma et al., 2019; Little & Welsh, 2022). As these minor misbehaviors are often judged based on subjective interpretation and contextual cues, minority students become more vulnerable to punitive actions than their White peers (Liu et al., 2023; Welsh, 2022). This raises concerns that ethnoracial imbalances in school discipline may result from teachers’ misjudgments rooted in implicit or explicit bias and insufficient understanding of diverse students (Girvan et al., 2017; Zimmermann & Cannady, 2025). Although teachers generally exhibit more positive racial attitudes than non-educators (Quinn, 2017), they are not immune to explicit or implicit bias against minorities (Starck et al., 2020). As the first observers of student misbehavior in the classroom, teachers’ unconscious prejudices and racial assumptions can shape their expectations for students from specific demographic groups (Kumar et al., 2015; Okura, 2022). Indeed, interventions designed to foster teachers’ knowledge of and empathy toward students have been shown to reduce suspension rates (Okonofua et al., 2022). Strong student–teacher relationships, developed by having the same teacher over multiple years, have also decreased the prevalence of challenging behaviors and disciplinary actions by improving understanding of student needs and characteristics (Hwang, n.d.). These findings suggest that teachers’ limited knowledge of and interaction with minority students have contributed to the disproportionate use of exclusionary discipline practices against the majority of minority students (Hughes et al., 2020; Steele, 1997; Tenenbaum & Ruck, 2007).

2.2. Ethnoracial (Mis)Match in School Discipline

Educators’ attitudes toward and empathy for children of color play a critical role in the observations and judgments of student behavior (Okonofua et al., 2016; Owens, 2022). A lack of quality intergroup interaction across race, ethnicity, and family circumstance often results in a failure to bring fundamental changes to stereotypes shaped by structural racism and entrenched racial prejudices (Hughes et al., 2017; Lowery et al., 2018). In the U.S. public school system, where the teaching workforce is predominantly composed of non-Hispanic White females (National Center for Education Statistics, 2020), limited exposure to teachers with the same race or similar cultural backgrounds can lead to an inevitable misalignment with the norms and values of students from marginalized groups (Hwang et al., 2024; Kozlowski, 2015; Welsh et al., 2023). Extensive research on racial and cultural congruence between teachers and students has demonstrated that students assigned to teachers of the same race tend to achieve better academic outcomes, exhibit improved cognitive skills, and develop stronger social and emotional competencies (Gershenson et al., 2022; Hart, 2020; Joshi et al., 2018; Redding, 2019; Wright et al., 2017; Yarnell & Bohrnstedt, 2017). Ethnoracial matching between teachers and students has also been proposed as a mechanism to ensure just judgments regarding behavioral corrections, office referrals, and exclusionary discipline. For instance, the probability that a student would be suspended during their academic year increased by 15% when taught by a different-race teacher, and this likelihood was particularly found for minority male students (Holt & Gershenson, 2019). Teachers’ ethnoracial attitudes, shaped or challenged by the mismatches with their children, have partly contributed to the abuse of exclusionary discipline against children from certain demographic and socioeconomic groups (Wymer et al., 2022). In a similar manner to the influence of the racial and ethnic congruence between students and classroom teachers on disciplinary situations (Annamma et al., 2019; Hwang et al., 2024; Santiago-Rosario et al., 2021), the race and ethnicity of school administrators play a significant role in decisions about punitive school discipline for students of color (Edwards et al., 2023; Giordano et al., 2020).

While the positive effects of same-race teachers on the outcomes for students of color have been well-documented through both rich longitudinal datasets and in-depth ethnographies, experiences of ethnoracial (mis)match between teachers and students have revealed substantial school and community variations in disciplinary outcomes, including office referrals, in-school suspensions, out-of-school suspensions, and expulsions, particularly for African American students (Hayes et al., 2023; Lindsay & Hart, 2017). Decisions to suspend non-White students out of school appeared less related to the race of teachers and school administrators, suggesting larger variabilities across schools than within schools (Anderson & Ritter, 2020; Kinsler, 2011). Face-to-face interracial interactions in instructional settings do not fully address ethnoracial disparities in school discipline (Freeman & Steidl, 2016; Koon et al., 2024). Instead, school discipline rates and the gaps between racial and ethnic groups have been linked to the demographic composition of the teacher workforce at the local education agency level (Hughes et al., 2020). Given that the details and processes of school policies—such as the deployment of police or use of metal detectors—often vary across school districts (Curran & Boza, 2023), nuanced local differences in disciplinary actions raise important questions about whether or not broadening the scope of intergroup relations beyond classrooms might offer deeper insight into the over- and underrepresentation of certain student groups in office referrals and suspensions (Koon et al., 2024). In light of the pronounced relationship between ethnoracial disparities in school disciplinary practices and community-level racial biases (Riddle & Sinclair, 2019), place-based perceptions of race and ethnicity may also account for inconsistent responses to student misconduct (Girvan, 2015; Meyers et al., 2023). While racial attitudes and prejudices within shared areas may re-shape and reinforce ethnoracial imbalances in student discipline indicators (Anderson & Ritter, 2020), much of the prior research has focused on the influence of ethnoracial mismatches between teachers and students within classroom settings. Taking into account the mixed effects of ethnoracial congruence between teachers and students and persistent concerns over racial threats in intergroup dynamics (Freeman & Steidl, 2016), ethnoracial disparities in student discipline call for further research on mismatches between teachers and the neighborhoods they serve.

In the United States, the teaching workforce, overwhelmingly female, has been highly localized, with many teachers preferring to work near where they live (Boyd et al., 2013; Engel & Cannata, 2015; Reininger, 2012). Because teacher hiring decisions and access to local labor markets heavily rely upon district-level networks (Jabbar et al., 2020), the embeddedness of teachers in their served communities can either reinforce or weaken their understanding of and biases toward students from different racial and ethnic backgrounds (Cannata, 2010; Clotfelter et al., 2011; Engel & Cannata, 2015). Moreover, collective attitudes within professional communities toward marginalized populations may intensify variations in the disproportionality of disciplinary referrals and suspensions between White and non-White students (Girvan et al., 2017). The interplay between teachers’ exposure to minority students and the socio-demographic context of school districts can disrupt the construction of shared understanding between teachers and students (Ding et al., 2021; Kozlowski, 2015). Frequent exposure to and growing familiarity with diverse students do not automatically lead to meaningful changes in teachers’ beliefs or attitudes about students’ race, ethnicity, and family circumstances (Lautenschlager & Omori, 2019; A. A. Payne & Welch, 2025). In other words, the ethnoracial match between teachers and their served communities may shape their disciplinary responses to student behavior-even when the behavior is the same. Since most studies on ethnoracial match in schools have examined face-to-face interactions between teachers and students in instructional environments, further research is needed to explore the potential of (mis)matches between teachers and the communities in which they work.

3. Data and Methods

This study examines racial disparities in in-school suspension in Tennessee with a focus on the potential link between the ethnoracial match of teachers and their served communities and student disciplinary outcomes. Compared to out-of-school suspensions and expulsions, in-school suspensions—which remove students displaying challenging behaviors from regular classrooms while keeping them in school buildings—can serve as a proxy for repeated school suspensions and an indicator of increased risk of academic failures (Anderson et al., 2019; Smith et al., 2021). Racial and ethnic disparities in in-school suspension are measured using risk ratios (RRs) and risk differences (RDs). These measurements compare the proportion of students who received in-school suspensions within a given ethnoracial group (SB) to the number of enrolled students in that given group (EB) and the proportion of White students who received in-school suspension (SW) to the number of enrolled White students (EW) (Curran, 2020). Given the population diversity in Tennessee, this study calculates the risk ratios and risk differences for African American, Hispanic or Latine/x, and non-White students, with White students as the reference group. These two measurements of disproportionality provide rich information about the likelihood of a given ethnoracial group being suspended compared to the counterpart body (Bottiani et al., 2023; Girvan et al., 2019). Risk ratios indicate how often a certain subgroup is suspended compared to the reference group, whereas risk differences offer a measure of the absolute difference between ethnoracial groups rather than relative magnitude. Data on ethnoracial disparities in in-school suspension between African American and White students, between Hispanic or Latine/x and White students, and between non-White and White students are sourced from the 2017–18 Civil Rights Data Collection collected by the Office of Civil Rights under the U.S. Department of Education. Measurements of racial disproportionality are listed below:

School neighborhoods, traditionally represented as school districts, play a substantial role in shaping teachers’ attitudes toward and engagement with students (Chin et al., 2020; B. K. Payne et al., 2017). Because ethnoracial variations in school discipline persist across schools and districts (Lee, 2023), this study defines a teachers’ served community as the school district level to assess ethnoracial congruence. This district-level approach offers insight into whether exposure to ethnoracially diverse populations within a school district can account for variations in the disproportionality of in-school suspensions between White and minority students (Girvan et al., 2017). This study uses the 2017–18 Educator Race and Ethnicity Data, collected by the Tennessee Department of Education, to obtain information on the proportions of White, African American, Hispanic or Latine/x, and other minority teachers in individual school districts. In Tennessee, where 82.0% of the teaching workforce is White, half of the state’s 140 school districts have teacher populations that are more than 94.7% White. Therefore, this study categorizes the Tennessee school districts into three groups: school districts where the percentage of White teachers is below the state average of 82.0%, those where the percentage exceeds the state median of 94.7%, and those falling in between. Since the demographic composition of school districts reflects broader community characteristics, this study also classifies communities by their White population share using the American Community Survey 5-year estimates for 2014–18. The average White population across Tennessee school districts is approximately 93.7%, ranging from 30.9% to 99.6%. Accordingly, the Tennessee school districts are grouped into three categories similar to the teachers’ served communities: communities with a White population of less than 79.6%, those with a White population higher than 93.7%, and those in between. An ethnoracially congruent school district is defined in this study as one with either high proportions of both White teachers and residents or low proportions of both.

With approximately 1500 schools nested in 140 school districts across 96 counties in Tennessee, this study employs district-level fixed effect regression models. In comparison with risk differences, risk ratios, which quantify racial and ethnic disproportionality in in-school suspension, follow a Poisson distribution with overdispersion and an excessive number of zeros. Therefore, this study uses a multilevel mixed effects zero-inflated negative binomial regression model to analyze risk ratios and a multilevel mixed effects regression model to assess risk differences. Because teacher mobility is generally limited within school districts rather than across local education agencies or state boundaries, teachers’ decisions to enter and remain in the workforce are often shaped by community characteristics (Clotfelter et al., 2011). Building on prior research on school and district segregation (Sosina & Weathers, 2019), this study incorporates key neighborhood factors such as the proportion of residents aged 25 years and older without a college degree, the proportion of unemployed individuals aged 16 years and older, and the log-transformed median household income. These community features are derived from the 2014–18 American Community Survey 5-year estimates provided by the U.S. Census. In addition to exploring the ethnoracial match between teachers and their served communities, this study includes information about educational environments such as log-transformed expenditures for instruction, the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced lunch, the proportion of non-White students, school level (primary schools serving kindergarten through eighth grade and high schools serving ninth through twelfth grades), and urbanity (i.e., whether schools are located in a town or rural area). This information is comprehensively derived from the Common Core Data at the National Center for Education Statistics and the Civil Rights Data Collection in the 2017–18 school year. The selected variables are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of the selected variables.

4. Findings

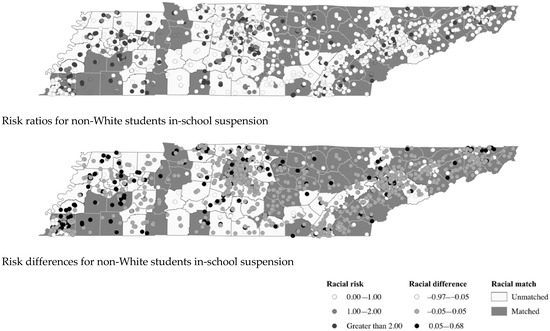

Given that the White population dominates the U.S. teacher workforce, recent studies about school disciplinary practices have increasingly addressed the issue that fair decisions on in-school suspension may occur in the context of ethnoracial congruence between teachers and diverse student populations. Figure 1 illustrates that school districts where teachers serve ethnoracially similar populations are geographically clustered rather than randomly dispersed across Tennessee. School districts where the demographic composition of teachers closely aligns with that of district residents, color-coded in grey, are primarily concentrated in eastern Tennessee. Many of these school districts in eastern Tennessee have a high proportion of White residents served by predominantly White teachers, or conversely higher minority populations served by a more diverse teaching staff. In contrast, the white-colored school districts in Figure 1 indicate that families primarily in central and western Tennessee are more likely to encounter a mismatch between the racial and ethnic backgrounds of teachers and the communities they serve, compared to the more congruent districts in eastern Tennessee.

Figure 1.

Ethnoracial match between teachers and communities with in-school suspensions in Tennessee.

Along with the pattern of ethnoracial congruence, Figure 1 also depicts the distribution of the risk ratios and differences in in-school suspensions for non-White students across Tennessee. Ethnoracial disparities in in-school suspensions vary both within and between school districts. Schools exhibiting low levels of racial and ethnic disproportionality in in-school suspensions, represented by white dots in Figure 1, are mainly observed in the ethnoracially similar school districts of eastern Tennessee. Although some schools with relatively small discipline gaps also appear in central and western Tennessee, those with risk ratios greater than 2.0, indicating substantial discipline disparities between White and non-White students, are more likely to be found in these central and western regions. Schools with moderate risk differences in in-school suspensions for non-White students, shown as light grey dots in Figure 1, are scattered throughout the state. However, schools where non-White students are at particularly high risk of in-school suspension compared to White students, marked by black dots in Figure 1, tend to be concentrated in ethnoracially mismatched school districts in central and western Tennessee.

Table 2 shows that ethnoracial congruence between teachers and their served communities is positively related to a reduction in racial and ethnic disparities in in-school suspension rates across Tennessee. In the null model, which examines disparities in in-school suspensions between White and African American students, schools situated in either predominantly White school districts with a high proportion of White teachers or diverse districts with diverse teacher compositions present a decrease of 0.670 in the risk ratios for in-school suspension. This finding suggests that ethnoracial alignment between teachers and the community contributes to fewer punitive actions toward African American students. Even after considering school- and neighborhood-level attributes, the full model for risk ratios in in-school suspension against African American students continues to show that racial disparities in in-school suspensions can be mitigated when teachers are racially and ethnically aligned with the communities they serve. In the Tennessee public school system, which serves a relatively small proportion of Hispanic or Latine/x students, the null model in Table 2 reveals a significant decline of 0.408 in the risk ratios for in-school suspension. Although the full model, which incorporates school and local community characteristics, presents no notable change in the ethnoracial disparity in exclusionary school discipline, the results still suggest a potential link between ethnoracial congruence and disciplinary equity for Hispanic or Latine/x students.

Table 2.

Racial match in the racial disproportionality of in-school suspension.

In the fourth column of Table 2, the findings for students of color demonstrate that the ethnoracial match between teachers and their served neighborhoods is linked to reduced risk ratios of in-school suspension compared to White students. This association between the demographic alignment of teachers with their school districts and the ethnoracial gaps in exclusionary practices weakens in comparison to the one observed for African American students. Nonetheless, non-White students in school districts whose populations correspond to the racial composition of the teaching workforce are still less likely to face exclusionary disciplinary actions. In other words, even with a smaller decline in the regression coefficients, the presence of ethnoracial congruence between teachers and their served communities remains positively related to narrowing the gap in in-school suspension. These findings support that increasing ethnoracial congruence between the teaching workforce and school communities may help reduce ethnoracial disparities in school discipline in Tennessee.

In comparison with the risk ratios indicator, which represents a relative magnitude of disproportionality, the risk differences indicator provides comparable information by capturing the absolute differences in in-school suspension rates across subgroups. Table 2 highlights significant differences in these ethnoracial gaps based on the ethnoracial congruence between teachers and the broader ethnoracial composition of the communities they serve. In the first and second columns for the risk differences, the null model reveals that schools where teachers serve a population of the same race are more likely to report smaller risk differences between African American and White students. A similar pattern is observed for Hispanic or Latine/x students, with a decline of 0.014 in the risk differences compared to White students. Although Table 2 delivers significant but small decreases in the risk differences in in-school suspension, all the full models, which incorporate additional contextual information, confirm that the ethnoracial match between teachers and their served populations is positively and consistently related to reduced disproportionality in in-school suspensions for minority students. This finding suggests that students of color are more likely to experience equitable treatment in disciplinary practices compared to White students when they attend schools in either predominantly White communities with mostly White teachers or racially diverse communities with a relatively lower proportion of White teachers.

This study also presents that community-level variability in in-school suspensions is greater when measured using the risk ratios than the risk differences. Given that 8.6 out of 10 teachers tend to remain in the same school district across consecutive years (Collins & Schaaf, 2020), ethnoracial disparities in in-school suspension are likely to persist among school districts in a relative, not absolute, magnitude. These findings from this study offer further insight into previous research on the association between neighborhood contexts and punitive school actions. As demonstrated in Table 2, community characteristics such as the proportion of White students, the percentage of individuals without a college degree, and housing prices continue to serve as strong proxies for persistent racial disproportionalities in school discipline. A higher proportion of White students in Tennessee public schools tends to lessen relative ethnoracial gaps in in-school suspensions in terms of risk ratios. However, it is not significantly associated with the overall difference in in-school suspension rates between ethnoracial groups.

Additionally, this study indicates an increase in the risk ratios but a decrease in the risk difference in in-school suspension at the high school level. The frequent use of exclusionary school discipline for high school students has raised concerns about equitable learning opportunities, regardless of students’ races and ethnicities (Welsh, 2022). As shown in Table 2, higher instructional expenditures per pupil are positively linked to declines in both the risk ratios and risk differences for non-White students. In a similar manner, log-transformed median housing prices contribute to reducing the gaps in exclusionary school discipline between African American or Hispanic/Latine/x and White students in both measurements and closing the relative magnitude in in-school suspension gaps between non-White and White students. Given that schools have reported inadequate or insufficient funding as a major constraint on efforts to reduce and prevent school crime (K. Wang et al., 2022), less affluent communities serving more economically disadvantaged students are more prone to use exclusionary discipline (Hughes, 2022; Taylor et al., 2023). This also suggests that wealthier districts are more likely to exhibit lower levels of disciplinary disproportionality, reinforcing the connection between local funding and equitable school outcomes. In the United States, where school district funding heavily relies on local property taxes, specifically housing prices, it is not surprising that school districts with greater investments in instruction tend to exhibit smaller disparities in school discipline across racial and ethnic groups. Furthermore, schools with a larger proportion of White students and more socioeconomically advantaged students have fewer suspended minority students, pointing to the complex interplay of race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and local school budgets in explaining disparities in school discipline (Diamond & Lewis, 2019; Welsh et al., 2025). Taken together, the findings of this study call for further research into how ethnoracial congruence between teachers and community members may help address persistent school discipline gaps. Because students of color are often overrepresented in economically disadvantaged populations due to the intersection of race and class, this study highlights the potential for teachers’ understanding of local neighborhood attributes to improve their responses to student misbehavior.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Current indicators of student discipline and trends in school safety have underscored the importance of multidimensional strategies for fostering quality learning environments (Hashim et al., 2018). Efforts to reform student discipline policies have recently incorporated restorative approaches to shape positive behavior, and some have reported overall declines in student suspension and expulsion rates (Craigie, 2022). Many studies on school discipline have also emphasized the pivotal role of teacher–student interactions within the classroom setting (Shirrell et al., 2024). However, amid a predominantly White, middle-class female teaching workforce in the United States, approximately half of the school-aged population—who are non-White—have had limited exposure to ethnoracially similar teachers. Furthermore, given the low job mobility in the teacher labor markets, the level of ethnoracial similarity between teachers and their served community has the potential to help explain the persistence of ethnoracial disparities in exclusionary discipline practices. Building on well-established research on student–teacher ethnoracial matching, this study explores whether demographic congruence between teachers and their served communities is related to racial and ethnic gaps in in-school suspensions by focusing on public schools in Tennessee. The findings from this study demonstrate that schools are less likely to show disparities in in-school suspensions between White and African American students, between White and Hispanic or Latine/x students, and between White and non-White students overall when White majority communities are served by predominantly White teachers or ethnoracially diverse communities employ relatively more non-White teachers. This study extends the discussion on racial and ethnic congruence in classroom and school settings by suggesting that the overrepresentation of minority students in school discipline may be shaped and intensified by the demographic composition of the teaching workforce relative to that of the local community. Similarly to how the ethnoracial match between teachers and students is known to yield academic and socioemotional benefits (Holt & Gershenson, 2019), ethnoracial congruence between teachers and communities, beyond the school fence, can play a substantial part in narrowing ethnoracial disparities in exclusionary practices.

Although the ethnoracial alignment between teachers and the communities they serve is more likely to reduce ethnoracially disproportionate disciplinary actions, progress in diversifying the teacher workforce has not kept pace with the growing diversity of the student populations. In Tennessee, most students have lacked access to minority teachers in core subjects, albeit with a great geographical variation (Binsted & Grissom, 2025). The insufficient representation of minority teachers in the American public school system hinders teachers from understanding and engaging with their school communities with diverse demographic and cultural capital (Hughes et al., 2020). Ethnoracial congruence between teachers and their served neighborhoods, as discussed in this study, offers a strong foundation for the implementation of culturally responsive teaching and learning. Culturally responsive practices have been shown to prevent student misbehavior and build positive relationships between demographically homogeneous teachers and diverse student populations (Larson et al., 2018; Williams et al., 2023). Previous research has indicated that culturally responsive engagement encourages minority students to skip school less often and improve their grade point averages (Bonilla et al., 2021; La Salle et al., 2020). Thus, integrating culturally responsive pedagogy into both learning and discipline has been emphasized to reduce racial disproportionalities in school discipline (Anyon et al., 2021; Dee & Penner, 2017).

In light of the underrepresentation of teachers of color in diverse communities, the findings from this study reiterate the broader significance of teachers’ experiences and attitudes toward communities of color, beyond the scope of direct classroom interactions. However, the current analysis defines ethnoracial matching between teachers and their served communities narrowly, focusing on a community with either high proportions of White teachers and residents or low proportions of White teachers and residents. Therefore, the observed declines in the ethnoracial imbalance of in-school suspension, shown in Table 2, may be limited to ethnoracially polarized school communities. When non-White students in a moderately diverse community are taught by majority White teachers, those teachers, albeit with a relatively high exposure to diverse community members, are more likely to take punitive actions against minority students. Given that disciplinary decisions on students’ challenging behaviors are based on subjective judgment and limited intergroup interactions, some teachers may feel less confident in navigating ambiguous situations in everyday school settings. This uncertainty can result in avoidance or misinterpretation of students from diverse backgrounds (Headley, 2022; Nicholson-Crotty et al., 2017). Such an aversive form of racism can intensify ethnoracial disparities in school discipline, as teachers who serve ethnoracially dissimilar communities may be less inclined to address student misbehavior.

Scholarly and public attention has been paid to the mismatch between predominantly White teachers and students of color from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. The alignment of racial, ethnic, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds between students and teachers not only cultivates more inclusive school environments but also helps reduce ethnoracial disparities in student discipline (Elmesky & Marcucci, 2023; Emslander et al., 2025; Shirrell et al., 2024). This study broadens the current discourse about ethnoracial congruence by suggesting the implication that racial and ethnic match between teachers and their served communities can shape disciplinary outcomes. However, given that teacher racial composition, rather than student demographics, has a stronger influence on how teachers perceive and address students’ misbehaviors (Martinez, 2020), mere exposure to different racial and ethnic groups in a shared space does not sufficiently mitigate tension across subgroups and can instead reinforce the misunderstanding of children and their families with different ethnoracial backgrounds (Qian et al., 2017; Welch & Payne, 2010). The limited quality of intergroup interaction through the student–teacher linguistic and cultural match justifies why teacher education and employment have increasingly placed value on the representativeness of minority teachers and ethnoracial diversity in schools and districts (Hughes et al., 2020; Thomas, 2020). Homegrown teachers often exhibit greater responsiveness to their served communities through a better understanding of minority groups, and those homegrown teachers of color are more likely to remain in their positions (Redding, 2022; Skinner & Riley, n.d.). The significance of ethnoracial congruence between teachers and their served school districts calls for deliberate professional development and management strategies to enhance awareness and understanding of students of color and prevent any biases in communities where there is ethnoracial misalignment between teachers and students (Skinner & Riley, n.d.). While this study offers insight into the comprehensive benefits of teacher diversity in ethnoracially and socioeconomically diverse school neighborhoods, it does not consider levels of school integration between and within school districts and patterns of teacher retention, or variations in teaching experiences. Future research can explore such local variations to delineate the importance of diversity in the U.S. teaching workforce for racial disparities in school discipline through reproducible and more rigorous research designs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and S.B.C.; data curation, methodology, visualization, and analysis, J.L.; writing, J.L. and S.B.C.; review, R.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created in this study. The data presented in this study are openly available in the United States Census Bureau (https://data.census.gov), the Office for Civil Rights (https://civilrightsdata.ed.gov), and the National Center for Education Statistics (https://nces.ed.gov/ccd/).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anderson, K. P., & Ritter, G. W. (2020). Do school discipline policies treat students fairly? Evidence from Arkansas. Educational Policy, 34(5), 707–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, K. P., Ritter, G. W., & Zamarro, G. (2019). Understanding a vicious cycle: The relationship between student discipline and student academic outcomes. Educational Researcher, 48(5), 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annamma, S. A., Anyon, Y., Joseph, N. M., Farrar, J., Greer, E., Downing, B. J., & Simmons, J. (2019). Black girls and school discipline: The complexities of being overrepresented and understudied. Urban Education, 54(2), 211–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyon, Y., Wiley, K., Samimi, C., & Trujillo, M. (2021). Sent out or sent home: Understanding racial disparities across suspension types from critical race theory and QuantCrit perspectives. Race Ethnicity and Education, 26(5), 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, N., McEachin, A., Mills, J. N., & Valant, J. (2021). Disparities and discrimination in student discipline by race and family income. The Journal of Human Resources, 56(3), 711–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, S., & Hoekstra, M. (2023). The effect of school and neighborhood peers on achievement, misbehavior, and adult crime. Journal of Labor Economics, 41(3), 643–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binsted, K., & Grissom, J. A. (2025). Which students are exposed to teachers of color? Peabody Journal of Education, 100(2), 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, S., Dee, T. S., & Penner, E. K. (2021). Ethnic studies increases longer-run academic engagement and attainment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(37), e2026386118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bottiani, J. H., Kush, J. M., McDaniel, H. L., Pas, E. T., & Bradshaw, C. P. (2023). Are we moving the needle on racial disproportionality? Measurement challenges in evaluating school discipline reform. American Educational Research Journal, 60(2), 293–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. H. (2013). Analyzing the determinants of the matching of public school teachers to jobs: Disentangling the preferences of teachers and employers. Journal of Labor Economics, 31(1), 83–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazil, N. (2016). The effects of social context on youth outcomes: Studying neighborhoods and schools simultaneously. Teachers College Record, 118(7), 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdick-Will, J. A. (2017). Neighbors but not classmates: Neighborhood disadvantage, local violent crime, and the heterogeneity of educational experiences in Chicago. American Journal of Education, 124, 37–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannata, M. (2010). Understanding the teacher job search process: Espoused preferences and preferences in use. Teachers College Record, 112(12), 2889–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capers, K. J. (2019). The role of desegregation and teachers of color in discipline disproportionality. The Urban Review, 51(5), 789–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M. J., Quinn, D. M., Dhaliwal, T. K., & Lovison, V. S. (2020). Bias in the air: A nationwide exploration of teachers’ implicit racial attitudes, aggregate bias, and student outcomes. Educational Researcher, 49(8), 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2011). Teacher mobility, school segregation, and pay-based policies to level the playing field. Education Finance and Policy, 6(3), 399–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, E., & Schaaf, K. (2020). Teacher retention in tennessee: Tennessee department of education division of research and analysis. Tennessee Department of Education. Available online: https://www.tn.gov/content/dam/tn/education/reports/TeacherRetentionReportFINAL.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Craigie, T.-A. (2022). Do school suspension reforms work? Evidence from Rhode Island. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 44(4), 667–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, F. C. (2020). A matter of measurement: How different ways of measuring racial gaps in school discipline can yield drastically different conclusions about racial disparities in discipline. Educational Researcher, 49(5), 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, F. C., & Boza, L. (2023). Community policing in schools and school resource officer transparency. Educational Policy, 37(6), 1573–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, F. C., Fisher, B. W., Viano, S. L., & Kupchik, A. (2019). Why and when do school resource officers engage in school discipline? The role of context in shaping disciplinary involvement. American Journal of Education, 126(1), 33–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dee, T. S., & Penner, E. K. (2017). The causal effects of cultural relevance: Evidence from an ethnic studies curriculum. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1), 127–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J. B., & Lewis, A. E. (2019). Race and discipline at a racially mixed high school: Status, capital, and the practice of organizational routines. Urban Education, 54(6), 831–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diliberti, M. K., Jackson, M. W., Correa, S., & Padgett, Z. (2019). Crime, violence, discipline, and safety in U.S. public schools: Findings from the school survey on crime and safety: 2017–18 first look (NCES 2019-061). National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2019/2019061.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Ding, F., Lu, J., & Riccucci, N. M. (2021). How bureaucratic representation affects public organizational performance: A meta-analysis. Public Administration Review, 81(6), 1003–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, W., Boggs, R., & Reyes, P. (2023). Student-principal racial/ethnic match, geographic locale, and student disciplinary outcomes. Journal of School Leadership, 33(3), 313–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmesky, R., & Marcucci, O. (2023). Beyond cultural mismatch theories: The role of antiblackness in school discipline and social control practices. American Educational Research Journal, 60(4), 769–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emslander, V., Holzberger, D., Ofstad, S. B., Fischbach, A., & Scherer, R. (2025). Teacher-student relationships and student outcomes: A systematic second-order meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 151(3), 365–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, M., & Cannata, M. (2015). Localism and teacher labor markets: How geography and decision making may contribute to inequality. Peabody Journal of Education, 90(1), 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, K. J., & Steidl, C. R. (2016). Distribution, composition and exclusion: How school segregation impacts racist disciplinary patterns. Race and Social Problems, 8, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlinger, J., Viano, S. L., Gardella, J. H., Fisher, B. W., Curran, F. C., & Higgins, E. M. (2021). Exclusionary school discipline and delinquent outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50, 1493–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershenson, S., Hart, C. M. D., Hyman, J. M., Lindsay, C. A., & Papageorge, N. W. (2022). The long-run impacts of same-race teachers. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 14(4), 300–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, K., Interra, V. L., Stillo, G. C., Mims, A. T., & Block-Lerner, J. (2020). Associations between child and administrator race and suspension and expulsion rates in community childcare programs. Early Childhood Education Journal, 49(1), 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girvan, E. J. (2015). On using the psychological science of implicit bias to advance anti-discrimination law. Civil Rights Law Journal, 26, 1–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girvan, E. J., Gion, C. M., McIntosh, K., & Smolkowski, K. (2017). The relative contribution of subjective office referrals to racial disproportionality in school discipline. School Psychology Quarterly, 32(3), 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girvan, E. J., McIntosh, K., & Smolkowski, K. (2019). Tail, tusk, and trunk: What different metrics reveal about racial disproportionality in school discipline. Educational Psychologist, 54(1), 40–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, D. C., Crosse, S., Tang, Z., Bauer, E. L., Harmon, M. A., Hagen, C. A., & Greene, A. D. (2020). Effects of school resource officers on school crime and responses to school crime. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(3), 905–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, C. M. D. (2020). An honors teacher like me: Effects of access to same-race teachers on black students’ advanced-track enrollment and performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 42(2), 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, A. K., Strunk, K. O., & Dhaliwal, T. K. (2018). Justice for all? Suspension bans and restorative justice programs in the Los Angeles Unified School District. Peabody Journal of Education, 93(2), 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, M. S., Liu, J., & Gershenson, S. (2023). Who refers whom? The effects of teacher characteristics on disciplinary office referrals. Economics of Education Review, 93, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headley, A. M. (2022). Representing personal and professional identities in policing: Sources of strength and conflict. Public Administration Review, 82(3), 396–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S. B., & Gershenson, S. (2019). The impact of demographic representation on absences and suspensions. Policy Studies Journal, 47(4), 1069–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C. (2022). The culture of control in schools: How punitive and disadvantaged spaces impact race-specific suspension rates. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 38(4), 384–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, C., Bailey, C. M., Warren, P. Y., & Stewart, E. A. (2020). “Value in diversity”: School racial and ethnic composition, teacher diversity, and school punishment. Social Science Research, 92, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, C., Warren, P. Y., Stewart, E. A., Tomaskovic-Devey, D., & Mears, D. P. (2017). Racial threat, intergroup contact, and school punishment. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 54(5), 583–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, N. (n.d.). The benefits of familiarity: The effects of repeated student-teacher matching on school discipline. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, N., Graff, P., & Berends, M. (2024). Racialized early grade (mis)behavior: The links between same-race/ethnicity teachers and discipline in elementary school. AERA Open, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, H., Cannata, M., Germain, E., & Castro, A. J. (2020). It’s who you know: The role of social networks in a changing labor market. American Educational Research Journal, 57(4), 1485–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, E., Doan, S., & Springer, M. G. (2018). Student-teacher race congruence: New evidence and insight from Tennessee. AERA Open, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsler, J. (2011). Understanding the Black-White school discipline gap. Economics of Education Review, 30(6), 1370–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koon, D. S.-V., Pham, H., Jordan, C., Chong, S., Haro, B. N., Harris, J. N., Huddlestunc, D., & Prim, J. (2024). Racial capitalism and student disposability in an era of school discipline reform. American Journal of Education, 130(2), 207–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlowski, K. P. (2015). Culture or teacher bias? Racial and ethnic variation in student–teacher effort assessment match/mismatch. Race and Social Problems, 7(1), 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R., Karabenick, S. A., & Burgoon, J. N. (2015). Teachers’ implicit attitudes, explicit beliefs, and the mediating role of respect and cultural responsibility on mastery and performance-focused instructional practices. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(2), 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupchik, A., & Henry, F. A. (2023). Generations of criminalization: Resistance to desegregation and school punishment. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 60(1), 43–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, K. E., Pas, E. T., Bradshaw, C. P., Rosenberg, M. S., Day-Vines, N. L., & Gregory, A. (2018). Examining how proactive management and culturally responsive teaching relate to student behavior: Implications for measurement and practice. School Psychology Review, 47(2), 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Salle, T. P., Wang, C., Wu, C., & Rocha Neves, J. (2020). Racial mismatch among minoritized students and White teachers: Implications and recommendations for moving forward. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 30(3), 314–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautenschlager, R., & Omori, M. (2019). Racial threat, social (dis)organization, and the ecology of police: Towards a macro-level understanding of police use-of-force in communities of color. Justice Quarterly, 36(6), 1050–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. (2023). Potential racial threat on student in-school suspensions in segregated U.S. neighborhoods. Education and Urban Society, 55(1), 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., & Movassaghi, K. S. (2021). The role of greenness of school grounds in student violence in the Chicago Public Schools. Children, Youth and Environments, 31(2), 54–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, C., & Hart, C. (2017). Exposure to same-race teachers and student disciplinary outcomes for Black students in North Carolina. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39, 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, S. J., & Welsh, R. O. (2022). Rac(e)ing to punishment? Applying theory to racial disparities in disciplinary outcomes. Race Ethnicity and Education, 25(4), 564–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Penner, E. K., & Gao, W. (2023). Troublemakers? The role of frequent teacher referrers in expanding racial disciplinary disproportionalities. Educational Researcher, 52(8), 469–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery, P. G., Burrow, J. D., & Kaminski, R. J. (2018). A multilevel test of the racial threat hypothesis in one state’s juvenile court. Crime & Delinquency, 64(1), 53–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M. J. (2020). Does school racial composition matter to teachers: Examining racial differences in teachers’ perceptions of student problems. Urban Education, 55(7), 992–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawene, D., & Bal, A. (2020). Spatial othering: Examining residential areas, school attendance zones, and school discipline in an urbanizing school district. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 28(91). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, C., Williams, A., Weisbuch, M., & Pauker, K. (2023). Bias contagion across racial group boundaries. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 47(4), 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, J. O. (2021). Exclusionary discipline policies, school-police partnerships, surveillance technologies and disproportionality: A review of the school to prison pipeline literature. The Urban Review, 53(5), 735–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2020). Race and ethnicity of public school teachers and their students (NCES 2020-103). National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020103/index.asp (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Nguyen, B. M. D., Noguera, P., Adkins, N., & Teranishi, R. T. (2019). Ethnic discipline gap: Unseen dimensions of racial disproportionality in school discipline. American Educational Research Journal, 56(5), 1973–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson-Crotty, S., Nicholson-Crotty, J., & Fernandez, S. (2017). Will more Black cops matter? Officer race and police-involved homicides of Black citizens. Public Administration Review, 77(2), 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonofua, J. A., Goyer, J. P., Lindsay, C. A., Haugabrook, J., & Walton, G. M. (2022). A scalable empathic-mindset intervention reduces group disparities in school suspensions. Science Advances, 8(12), eabj0691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonofua, J. A., Walton, G. M., & Eberhardt, J. L. (2016). A vicious cycle: A social-psychological account of extreme racial disparities in school discipline. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(3), 381–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okura, K. (2022). Stereotype promise: Racialized teacher appraisals of Asian American academic achievement. Sociology of Education, 95(4), 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, J. (2022). Double jeopardy: Teacher biases, racialized organizations, and the production of racial/ethnic disparities in school discipline. American Sociological Review, 87(6), 1007–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J., & Favero, N. (2023). Race, locality, and representative bureaucracy: Does community bias matter? Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 33(4), 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A. A., & Welch, K. (2025). Minority threat in schools and differential security manifestations: Examining unequal control, surveillance, and protection. Crime & Delinquency, 71(6–7), 2276–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, B. K., Vuletich, H. A., & Lundberg, K. B. (2017). The bias of crowds: How implicit bias bridges personal and systemic prejudice. Psychological Inquiry, 28(4), 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, M. K., Heyman, G. D., Quinn, P. C., Fu, G., & Lee, K. (2017). When the majority becomes the minority: A longitudinal study of the effects of immersive experience with racial out-group members on implicit and explicit racial biases. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(6), 914–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, D. M. (2017). Racial attitudes of preK–12 and postsecondary educators: Descriptive evidence from nationally representative data. Educational Researcher, 46, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raney, M. A., Hendry, C. F., & Yee, S. (2019). Physical activity and social behaviors of urban children in green playgrounds. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(4), 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redding, C. (2019). A teacher like me: A review of the effect of student-teacher racial/ethnic matching on teacher perceptions of students and student academic and behavioral outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 89(4), 499–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redding, C. (2022). Are homegrown teachers who graduate from urban districts more racially diverse, more effective, and less likely to exit teaching? American Educational Research Journal, 59(5), 939–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reininger, M. (2012). Hometown disadvantage? It depends on where you’re from. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 34(2), 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddle, T., & Sinclair, S. (2019). Racial disparities in school-based disciplinary actions are associated with county-level rates of racial bias. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(17), 8255–8260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago-Rosario, M. R., Whitcomb, S. A., Pearlman, J., & McIntosh, K. (2021). Associations between teacher expectations and racial disproportionality in discipline referrals. Journal of School Psychology, 85, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirrell, M., Bristol, T. J., & Britton, T. A. (2024). The effects of student–teacher ethnoracial matching on exclusionary discipline for Asian American, Black, and Latinx students: Evidence from New York City. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 46(3), 555–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. A., & Riley, A. (n.d.). Community immersion for homegrown teachers: Learning “there are never just negatives…”. Urban Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D., Ortiz, N. A., Blake, J. J., Marchbanks, M., Unni, A., & Peguero, A. A. (2021). Tipping point: Effect of the number of in-school suspensions on academic failure. Contemporary School Psychology, 25(4), 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolkowski, K., Girvan, E. J., McIntosh, K., Nese, R. N. T., & Horner, R. H. (2016). Vulnerable decision points in school discipline: Comparison of discipline for African American compared to White students in elementary schools. Behavioral Disorders, 41(4), 178–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosina, V. E., & Weathers, E. S. (2019). Pathways to inequality: Between-district segregation and racial disparities in school district expenditures. AERA Open, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starck, J. G., Riddle, T., Sinclair, S., & Warikoo, N. (2020). Teachers are people too: Examining the racial bias of teachers compared to other American adults. Educational Researcher, 49(4), 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, J.-P., Zuber, M., & Shoup, D. (2023). Determinants of school discipline: Examination of institutional level factors impacting exclusionary sanctions. Youth & Society, 55(3), 581–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenenbaum, H. R., & Ruck, M. D. (2007). Are teachers’ expectations different for racial minority than for European American students? A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(2), 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. B. (2020). “Please hire more teachers of color”: Challenging the “good enough” in teacher diversity efforts. Equity & Excellence in Education, 53(1–2), 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K., Chen, Y., Zhang, J., & Oudekerk, B. A. (2020). Indicators of school crime and safety: 2019 (NCES 2020-063). National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2020/2020063.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Wang, K., Kemp, J., Burr, R., & Swan, D. (2022). Crime, violence, discipline, and safety in U.S. public schools in 2019–20: Findings from the school survey on crime and safety (NCES 2022-029). National Center for Education Statistics. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2022/2022029.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Wang, S., Graham, J., Flamini, M., & Cevik, S. (2023). Linking teacher quality and school discipline disproportionality. Journal of Education Human Resources, 41(4), 729–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, K., & Payne, A. A. (2010). Racial threat and punitive school discipline. Social Problems, 57(1), 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, R. O. (2022). Schooling levels and school discipline: Examining the variation in disciplinary infractions and consequences across elementary, middle, and high schools. Journal of Education for Students Placed at Risk, 27(3), 270–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, R. O., & Little, S. (2018). The school discipline dilemma: A comprehensive review of disparities and alternative approaches. Review of Educational Research, 88(5), 752–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, R. O., Rodriguez, L. A., & Joseph, B. (2025). Racial threat, schools, and exclusionary discipline: Evidence from New York City. Sociology of Education, 98(2), 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsh, R. O., Rodriguez, L. A., & Joseph, B. B. (2023). Beating the school discipline odds: Conceptualizing and examining inclusive disciplinary schools in New York City. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 34(3), 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkerson, K. L., & Afacan, K. (2022). Repeated school suspensions: Who receives them, what reasons are given, and how students fare. Education and Urban Society, 54(3), 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. A., III, Mallant, C., & Svajda-Hardy, M. (2023). A gap in culturally responsive classroom management coverage? A critical policy analysis of states’ school discipline policies. Educational Policy, 37(5), 1191–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A., Gottfried, M. A., & Le, V.-N. (2017). A kindergarten teacher like me: The role of student-teacher race in social-emotional development. American Educational Research Journal, 54(1S), 78S–101S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wymer, S. C., Corbin, C. M., & Williford, A. P. (2022). The relation between teacher and child race, teacher perceptions of disruptive behavior, and exclusionary discipline in preschool. Journal of School Psychology, 90, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarnell, L. M., & Bohrnstedt, G. W. (2017). Student-teacher racial match and its association with Black student achievement: An exploration using multilevel structural equation modeling. American Educational Research Journal, 55(2), 287–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, C. R., & Cannady, E. (2025). More than teacher bias: A QuantCrit analysis of teachers’ perceptions of young Black boys’ noncognitive skills. Social Problems, 72(1), 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinsser, K. M., Silver, H. C., Shenberger, E. R., & Jackson, V. (2022). A systematic review of early childhood exclusionary discipline. Review of Educational Research, 92(5), 743–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).