Promoting Reading and Writing Development Among Multilingual Students in Need of Special Educational Support: Collaboration Between Heritage Language Teachers and Special Educational Needs Teachers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Pedagogical Collaboration Supporting Multilingual Reading and Writing Development

3. Promoting CALP Among Multilingual Students

4. Teaching Basic Reading and Writing to Students at Pre-Reading Stages

5. The Current Study

6. Study 1: Questionnaire Study

6.1. Materials and Methods Study 1

6.1.1. Participants Study 1

6.1.2. Materials and Procedure Study 1

6.1.3. Analysis Study 1

6.2. Results Study 1

6.2.1. No Collaboration

6.2.2. Collaboration

- Assessing students’ learning difficulties

- Receiving guidance when teaching students in need of special education

6.3. Discussion Study 1

7. Study 2: In-Depth Interviews

7.1. Materials and Methods Study 2

7.1.1. Participants Study 2

7.1.2. Materials and Procedure Study 2

7.1.3. Analysis Study 2

7.2. Results Study 2

7.3. Promoting CALP

7.3.1. Promoting CALP in the Role of Mother Tongue Teacher

Interviewer: How do you, as a mother tongue teacher and multilingual study guidance tutor contribute to the student’s reading and writing development?HLT 3: I contribute in both L1 and Swedish. […] It is very important that my students learn both languages. […] During mother tongue lessons, they do so by reading, writing, talking and meeting others. They discuss and adapt the language, increase vocabulary by talking about different things. […] During mother tongue lessons, we try to learn to write and read correctly. […] We work with books. With younger students I work on reading and reading comprehension or on the writing of a simple book.

I try to divide students into different groups. that is, those who are beginners and then those who know a lot of L1. We teach the entire spectrum. Students who know nothing and then those who have recently moved from L1 Country. […] We also teach preschool students [to] students who are in 9th grade.(HLT 13)

In L1 Country we have 23 official languages. And I teach students from all the different continents. […] I teach English, which is a huge language. My students come from the USA, Australia, India, Nigeria, Great Britan and some other countries. Many different countries and cultures. But I am used to differences from my home country.

7.3.2. Promoting CALP in Their Role as Study Guidance Tutors

“When the students are newly arrived in Sweden, it is not enough to just translate words. Because they don’t understand much of the system. […] you cannot just translate the words […]. You must first translate the concepts and explain the context. […].”(HLT3)

“It’s not just with students that I work with. I explain to the parents too. During the parent-teacher-talk, for example. […] Because the criteria and requirements for reaching a grade are different here than in L1-Country.”(HLT1)

7.4. Teaching Basic Reading and Writing to Multilingual Students at Pre-Reading Stages

HLT 12: We started with basic reading and writing.Interviewer: You mean with preschool students?HLT 12: No, not only. There are also older students who cannot read and write. For example, they have not gone to school in their home country. So, they are older than their Swedish classmates. One student I’m working with right now is in fifth grade. But they can be even older.

You can’t work with their literacy development according to their biological age. Some need to work with materials for younger students. […] We often start with the alphabet. […] When they can write letters, we work with easy Swedish books.

“He has never gone to school in his L1. He spent years in refugee camps, where he went to Religion schools in another language than his L1. A language with another alphabet [than his L1 and Swedish]”.

“She has basic knowledge of the subject in her mother tongue and reasons in a very adult way. […] We only had to work on spelling in Swedish, then writing short Swedish words of 3–4 letters.”

I regularly talk to the parents. […] Some of them don’t have an education themselves. For instance, one mother was illiterate when she came to Sweden. So, it’s not easy for her to deal with [her daughter’s school] problems or tell the teacher what the problem is. She just says, I’m really worried about my daughter.

7.5. Assessing and Supporting Students with SEN

HLT 6: I taught a student once who had difficulties, learning difficulties. […] when I heard from the SEN teacher that [the student] should either go to a school for pupils with intellectual disabilities or they should adapt their teaching methods to the student’s needs, I contacted the SEN teacher and asked if I could get some advice on how I should work with the student.Interviewer: Did you get any good tips?HLT 6: Yes, we shouldn’t read and write much. But, when I asked what the student had, they only said difficulties. They did not want to specify what kind of difficulties.

7.6. Discussion Study 2

8. General Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Translation of the Questionnaire

Appendix B

| Participant | Education | Work Experience |

|---|---|---|

| HL1 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 11 or more years |

| HL2 | Other university degree from another country | 0–2 years |

| HL3 | Degree in teaching and learning from another country | 11 or more years |

| HL4 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 3–5 years |

| HL5 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 11 or more years |

| HL6 | Other university degree from another country | 6–10 years |

| HL7 | Other university degree from another country | 6–10 years |

| HL8 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 0–2 years |

| HL9 | Degree in teaching and learning from another country | 11 or more years |

| HL10 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 11 or more years |

| HL11 | Degree in teaching and learning from another country | 6–10 years |

| HL12 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 3–5 years |

| HL13 | Degree in teaching and learning from another country | 11 or more years |

| HL14 | Other university degree from another country | 11 or more years |

| HL15 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 11 or more years |

| HL16 | Other university degree from another country | 11 or more years |

| HL17 | Degree in teaching and learning from another country | 0–2 years |

| HL18 | Degree in teaching and learning from another country | 0–2 years |

| HL19 | Other university degree from another country | 11 or more years |

| HL20 | Other university degree from another country | 11 or more years |

| HL21 | Other university degree from another country | 11 or more years |

| HL22 | Other university degree from another country | 0–2 years |

| HL23 | Other university degree from another country | 11 or more years |

| HL24 | Degree in teaching and learning from another country | 6–10 years |

| HL25 | Degree in teaching and learning from another country | 11 or more years |

| HL26 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 11 or more years |

| HL27 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 6–10 years |

| HL28 | Other university degree from Sweden | 11 or more years |

| HL29 | Degree in teaching and learning from another country | 11 or more years |

| HL30 | Other university degree from another country | 6–10 years |

| HL31 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 0–2 years |

| HL32 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 11 or more years |

| HL33 | Degree in teaching and learning from Sweden | 11 or more years |

Appendix C

| Teaching in |

|---|

| Albanian |

| Amharic |

| Arabic |

| Assyrian |

| Bosnian |

| Chaldean |

| Chinese |

| Croatian |

| Dari |

| English |

| Finnish |

| French |

| German |

| Italian |

| Kirundi |

| Kurdish (Badini) |

| Kurdish (Kurmanji) |

| Kurdish (Sorani) |

| Persian |

| Polish |

| Portuguese |

| Russian |

| Serbian |

| Somali |

| Spanish |

| Thai |

| Tigrinya |

| Turkish |

| Ukrainian |

Appendix D

| Teaching in |

|---|

| Albanian |

| Arabic |

| Bengali |

| Chinese |

| English |

| Finnish |

| French |

| Greek |

| Kurdish (Kurmanji) |

| Polish |

| Somali |

| Syriac |

| Tagalog |

| Tigrinya |

| Urdu |

Appendix E

| Heritage Language Teacher | Education | Working Years as HLT in Sweden |

|---|---|---|

| HLT 1 | University degree in National Economics from home country. | 5 |

| HLT 2 | General Swedish college degree. | 2–5 |

| HLT 3 | University degree in Ethnology from home country. University degree in Multilingual Study Guidance from Sweden. | 7 |

| HLT 4 | University degree in International Relations and in science from home country. University degree in English from Sweden. About to start Swedish teacher training at a Swedish university. | 5 |

| HLT 5 | Some Swedish university credits in Mother Tongue Instruction and Multilingual Study Guidance. Some other university credits relevant for working with children affected by mobility on | 10 |

| HLT 6 | University degree in English from home country. | 5 |

| HLT 7 | University degree in Music and Teaching and Learning from home country. University degrees in Mother Tongue Instruction and Language Teaching from Sweden. | 3 |

| HLT 8 | University degree in Teaching and Learning and Psychology from home country. Studies in Teaching and Learning at a Swedish university are ongoing. | 5 |

| HLT 9 | University degree in Teaching and Learning in Mathematics from home country. Studies in Teaching and Learning in Sweden ongoing. | 4 |

| HLT 10 | University degree in Teaching and Learning from home country. | 11 |

| HLT 11 | University degree in Teaching and Learning from home country. | 5 |

| HLT 12 | Swedish college degree in Childcare. Some university credits in Multilingual Study Guidance from Sweden. | 6–10 |

| HLT 13 | University degree in Teaching and Learning and Finnish Literature from home. University degree in Ethnology Sweden. | 17 |

Appendix F. A Sample of the Digital Questionnaire (Translated from Swedish)

Appendix G. Translated Interview Guide

References

- Abrahamsson, N., Hyltenstam, K., Bylund, E., Bartning, I., & Fant, L. (2018). Age effects on language acquisition, retention and loss: Key hypotheses and findings. In High-level language proficiency in second language and multilingual contexts (pp. 16–49). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agar, M., & Hobbs, J. R. (1982). Interpreting discourse: Coherence and the analysis of ethnographic interviews. Discourse Processes, 5(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aichberger, M. C., Bromand, Z., Rapp, M. A., Yesil, R., Montesinos, A. H., Temur-Erman, S., Heinz, A., & Schouler-Ocak, M. (2015). Perceived ethnic discrimination, acculturation, and psychological distress in women of Turkish origin in Germany. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(11), 1691–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, A., Sayehli, S., & Gullberg, M. (2019). Language background affects online word order processing in a second language but not offline. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 22(4), 802–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, H. (2015). Teaching in the “edgelands” of the school day: The organization of mother tongue studies in a highly diverse Swedish primary school. Power and Education, 7(2), 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelsson, M., & Magnusson, U. (2012). Forskning om flerspråkighet och kunskapsutveckling under skolåren. In K. Hyltenstam, M. Axelsson, & I. Lindberg (Eds.), Flerspråkighet—En forskningsöversikt. Vetenskapsrådet. [Google Scholar]

- Baeten, M., & Simons, M. (2014). Student teachers’ team teaching: Models, effects and conditions for implementation. Teacher and Teaching Education, 41, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauler, C. V., & Kang, E. J. S. (2020). Elementary ESOL and content teachers’ resilient co-teaching practices: A long-term analysis. International Multilingual Research Journal, 14(4), 338–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelow, M., & Tarone, E. (2004). The role of literacy level in second language acquisition: Doesn’t who we study determine what we know? TESOL Quarterly, 38(4), 689–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Stoll, L., Thomas, S., & Wallace, M. (2005). Creating and sustaining effective professional learning communities (Vol. 637, pp. 1–211). Department for Education and Skills. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfiglio, T. P. (2010). Mother tongues and nations: The invention of the native speaker. De Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, A., Rothlein, L., & Hurley, M. (1996). Vocabulary acquisition from listening to stories and explanations of target words. The Elementary School Journal, 96(4), 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, L. R. (2003). A model for interdisciplinary collaboration. Social Work, 48(3), 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L. L. S., & Sylva, K. (2015). Exploring emergent literacy development in a second language: A selective literature review and conceptual framework for research. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 15(1), 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, A. L., & Smith, S. A. (2020). Bilingual children who stutter: Convergence, gaps and directions for research. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 63, 105741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioè-Peña, M. (2017). The intersectional gap: How bilingual students in the United States are excluded from inclusion. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(9), 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, V. (2016). Where is the native speaker now? TESOL Quarterly, 50, 186–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creese, A. (2006). Supporting talk? Partnership teachers in classroom interaction. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 9(4), 434–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, J. (2000a). Andraspråksundervisning för skolframgång—En modell för utveckling av skolans språkpolicy. In K. Nauclér (Ed.), Symposium 2000—Ett andraspråksperspektiv på lärande (pp. 86–107). Libris. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. (2000b). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. (2001). Negotiating identities: Education for empowerment in a diverse society (2nd ed.). California Association for Bilingual Education. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. (2008). BICS and CALP: Empirical and theoretical status of the distinction. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 2(2), 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, J. (2017). Flerspråkiga elever. Effektiv undervisning i en utmanande tid. Natur & Kultur. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila, L. T., & Bunar, N. (2020). Translanguaging through an advocacy lens: The roles of multilingual classroom assistants in Sweden. European Journal of Applied Linguistics, 8(1), 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewaele, J. M. (2018). Why the dichotomy “L1 versus LX user” is better than “native versus non-native speaker”. Applied Linguistics, 39, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elley, W. B. (1989). Vocabulary acquisition from listening to stories. Reading Research Quarterly, 24(2), 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frates, A., Spooner, F., Bear, C., Frates, A., Spooner, F., Collins, B. C., & Running Bear, C. (2022). Vocabulary acquisition by multilingual students with extensive support needs during shared reading. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities: The Journal of TASH, 47(3), 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganuza, N., & Hedman, C. (2018). Modersmålsundervisning, läsförståelse och betyg—Modersmålsundervisningens roll för elevers skolresultat. Nordand, 13(1), 4–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganuza, N., & Sayehli, S. (2020). Forskning om flerspråkighet. Skolverket. [Google Scholar]

- García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard, Y. L., Goddard, R. D., & Tschannen-Moran, M. (2007). Theoretical and empirical investigation of teacher collaboration for school improvement and student achievement in public elementary schools. Teachers College Record, 109(4), 877–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göransson, K., Lindqvist, G., Möllås, G., Almqvist, L., & Nilholm, C. (2017). Ideas about occupational roles and inclusive practices among special needs educators and support teachers in Sweden. Educational Review, 69(4), 490–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göransson, K., Lindqvist, G., & Nilholm, C. (2015). Voices of special educators in Sweden: A total-population study. Educational Research, 57(3), 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groff, C., Zwaanswijk, W., Wilson, A., & Saab, N. (2023). Language diversity as resource or as problem? Educator discourses and language policy at high schools in the Netherlands. International Multilingual Research Journal, 17(2), 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, M. (2006). Ethnograpy: Problems and prospects. Ethnography and Education, 1(1), 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedman, C., & Magnusson, U. (2023). Adjusting to linguistic diversity in a primary school through relational agency and expertise: A mother-tongue teacher team’s perspective. Multilingual, 42(1), 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, E. (2003). The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Development, 74(5), 1368–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, K. B., Katsos, N., & Gibson, J. L. (2021). Practitioners’ perspectives and experiences of supporting bilingual pupils on the autism spectrum in two linguistically different educational settings. British Educational Research Journal, 47(2), 427–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, N., Bartolo, P., Ale, P., Calleja, C., Hofsaess, T., Janikova, V., Lous, A. M., Vilkiene, V., & Wetso, G. (2006). Understanding and responding to diversity in the primary classroom: An international study. European Journal of Teacher Education, 29(3), 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyltenstam, K., & Lindberg, I. (Eds.). (2013). Svenska som andraspråk–i forskning, undervisning och samhälle. Studentlitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Hyltenstam, K., & Milani, T. M. (2012). Flerspråkighetens sociopolitiska och sociokulturella ram. In I. K. Hyltenstam, M. Axelsson, & I. Lindberg (Eds.), Flerspråkighet: En forskningsöversikt. Vetenskapsrådet. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, S., & Pavlenko, A. (2007). Crosslinguistic influence in language and cognition. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Krulatz, A., & Iversen, J. (2020). Building inclusive language classroom spaces through multilingual writing practices for newly arrived students in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(3), 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvale, S., & Brinkman, S. (2014). Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun. Studentlitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Lahdenperä, P. (2000). From monocultural to intercultural educational research. Intercultural Education, 11(2), 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasagabaster, D. (2018). Fostering team teaching: Mapping out a research agenda for English medium instruction at university level. Language Teaching, 51(3), 400–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaScotte, D. (2020). Leveraging listening texts in vocabulary acquisition for low-literate learners. TESL Canada Journal=Revue TESL Du Canada, 37(1), 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leana, C. R., & Pil, F. (2006). Social capital and organizational performance: Evidence from urban public schools. Organization Science, 17(3), 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindberg, I. (2009). I det nya mångspråkiga Sverige. Utbildning & Demokrati—Tidskrift för Didaktik och Utbildningspolitik, 18(2), 9–37. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, I., & Sandwall, K. (2012). Samhälls-och undervisningsperspektiv på svenska som andraspråk för vuxna invandrare. In I. K. Hyltenstam, M. Axelsson, & I. Lindberg (Eds.), Flerspråkighet—En forskningsöversikt. Vetenskapsrådet. [Google Scholar]

- Lokhande, M., & Reichle, B. (2019). Acculturation and school adjustment of children and youth from culturally diverse backgrounds: Predictors and interventions for school psychology. Journal of School Psychology, 75, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes-Murphy, S. A. (2020). Contention between English as a second language and special education services for emergent bilinguals with disabilities. Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, 13(1), 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinova-Todd, S. H., Colozzo, P., Mirenda, P., Stahl, H., Kay-Raining Bird, E., Parkington, K., Cain, K., Scherba de Valenzuela, J., Segers, E., MacLeod, A. A. N., & Genesee, F. (2016). Professional practices and opinions about services available to bilingual children with developmental disabilities: An international study. Journal of Communication Disorders, 63, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez, G. A. (2003). Classroom based dialect awareness in heritage language instruction: A critical applied linguistic approach. Heritage Language Journal, 1(1), 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molle, D., & Huang, W. (2021). Bridging science and language development through interdisciplinary and interorganizational collaboration: What does it take? Science Education International, 32(2), 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, T., Singer, G., & Carranza, F. (2006). A national survey of the educational planning and language instruction practices for students with moderate to severe disabilities who are English language learners. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 31(3), 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obondo, M. A., Lahdenperä, P., & Sandevärn, P. (2016). Educating the old and newcomers: Perspectives of teachers on teaching in multicultural schools in Sweden. Multicultural Education Review, 8(3), 176–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otterup, T. (2019). 14. Multilingual Students in a CLIL School: Possibilities and Perspectives. In L. Sylvén (Ed.), Investigating content and language integrated learning: Insights from Swedish high schools (pp. 263–281). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Penno, J. F., Wilkinson, I. A. G., & Moore, D. W. (2002). Vocabulary acquisition from teacher explanation and repeated listening to stories: Do they overcome the Matthew Effect? Journal of Educational Psychology, 94(1), 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, F. L., Jr. (2011). Research in applied linguistics: Becoming a discerning consumer. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- PISA. (2022). 15-åringars kunskaper i matematik, läsförståelse och naturvetenskap. Skolverket. [Google Scholar]

- Reath Warren, A. (2013). Mother tongue tuition in Sweden—Curriculum analysis and classroom experience. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 6(1), 95–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ringbom, H. (2007). Cross-linguistic similarity in foreign language learning (1st ed., Vol. 21). Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosén, J. (2013). Svenska för invandrarskap? Språk, kategorisering och identitet inom utbildningsformen Svenska för invandrare [Doctoral thesis, Örebro University]. [Google Scholar]

- Rosén, J., Straszer, B., & Wedin, Å. (2019). Studiehandledning på modersmål: Studiehandledares positionering och yrkesroll. Educare, 3(3), 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux Sparreskog, C. (2018). “Välkommen till 3a!”:–En etnografisk fallstudie om språkutvecklande undervisning i ett språkligt och kulturellt heterogent klassrum. Mälardalens Universitet. [Licentiatuppsats]. [Google Scholar]

- Roux Sparreskog, C. (2025). Didaktiskt samarbete för stöttning av flerspråkiga elevers språk-och kunskapsutveckling [Doctoral thesis, Mälardalens University]. [Google Scholar]

- Salameh, E. K. (2003). Language impairment in Swedish bilingual children-epidemiological and linguistic studies [Doctoral dissertation, Lund University]. [Google Scholar]

- Sheikhi, K. (2019). Samarbete för framgångsrik studiehandledning på modersmål. Skolverket. [Google Scholar]

- SOU. (2019). För flerspråkighet, kunskapsutveckling och inkludering. Modersmålsundervisning och studiehandledning på modersmåls. Betänkande av utredning om modersmål och studiehandledning på modersmål i grundskola och motsvarande skolformer. Utbildningsdepartementet. [Google Scholar]

- Sparreskog, C. R. (2025). In between the fields of research of special educational needs and multilingual education—Swedish heritage language teachers’ perspectives on special educational needs in multilingual students. European Educational Research Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, T., & Perry, B. (2005). Interdisciplinary team teaching as a model for teacher development. TESL-EJ, 9(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE]. (2015). Studiehandledning på modersmålet—Att stödja kunskapsutvecklingen hos flerspråkiga elever. Skolverket. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE]. (2018). Greppa flerspråkighet. Skolverket. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE]. (2021). PIRLS 2021—Läsförmågan hos svenska elever i årskurs 4 i ett internationellt perspektiv. Skolverket. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE]. (2022). Curriculum for compulsory school, preschool class and school-age educare—Lgr22. Skolverket. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE]. (2025a). Elever i grundskola med särskilt stöd och studiehandledning på modersmål uppdelat per områdestyp samt totalt läsåret 2024/25. Skolverket. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish National Agency for Education [SNAE]. (2025b). Elever och skolenheter i grundskolan Läsåret 2042/24. Skolverket. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Research Council. (2017). Good research practice. Vetenskapsrådet. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Research Council. (2024). Good research practice. Vetenskapsrådet. [Google Scholar]

- The Swedish Language Act. (2009). The language act, 2009:600, section 14, Språklagen (SFS 2009:600). Regeringskansliet. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal, K. (2003). Academic listening: A source of vocabulary acquisition? Applied Linguistics, 24(1), 56–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, K. (2011). A comparison of the effects of reading and listening on incidental vocabulary acquisition. Language Learning, 61(1), 219–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorenpää, S., & Zetterholm, E. (2020). Modersmålslärare—Så mycket mer än bara språklärare. In B. Straszer, & Å. Wedin (Eds.), Modersmål, minoriteter och mångfald: I förskola och skola. Studentlitteratur. [Google Scholar]

- Wedin, Å., & Wessman, A. (2017). Multilingualism as policy and practices in elementary school: Powerful tools for inclusion of newly arrived pupils. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 9(4), 873–890. [Google Scholar]

- Wermke, W., & Beck, I. (2025). Power and inclusion. German and Swedish special educators’ roles and work in inclusive schools. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 69(1), 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B. (2023). Classroom study of teacher collaboration for multilingual learners: Implications for teacher education programs. Action in Teacher Education, 45(2), 124–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Theme | Description | Supporting Statements (Translated from Swedish) |

|---|---|---|

| No collaboration | Of the 33 who answered the questionnaire, 17 reported that they had never collaborated with SEN teachers. | “I never even have met a SEN teacher” (HL teacher 13). |

| Collaboration when assessing students’ learning difficulties | The SEN teacher contributes his/her SEN knowledge and the HL teacher his/her L1 knowledge. They jointly discuss the students’ needs. | “We exchange information about the student to detect the reasons behind his/her language deficiencies or other problems” (HL teacher 15). “We meet and discuss the student’s difficulties and how we can help him/her” (HL teacher 18). |

| Collaboration when receiving guidance when teaching students in need of special education | When HL teachers feel that their knowledge is not enough to support students, they seek help and support from SEN teachers. SEN teachers provide materials, strategies, and guidance. | “in order to offer all my students adequate support” (HL teacher 19). “The SEN teacher provides me with teaching materials” (HL teacher 32). “The SEN teacher introduces me to digital aids and learning strategies” (HL teacher 9). |

| Theme | Description | Supporting Statement |

|---|---|---|

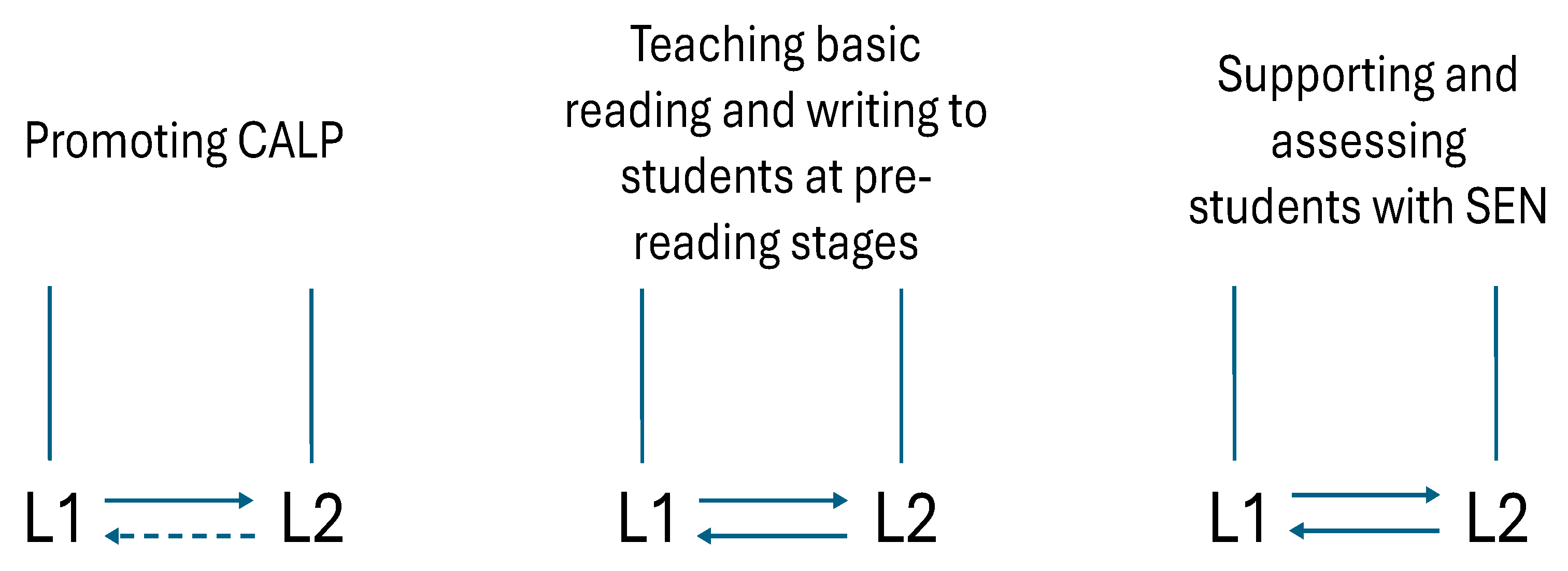

| Promoting CALP | Mother tongue class: Promoting L1 and L2 CALP. The mastery of the different languages influences each other. Strong L1 -> faster learning of and stronger L2. Curriculum: Reading, writing, talking. Linguistic and age-wise variation in mother tongue classes: Individualized teaching methods. | “I contribute in both L1 and Swedish. […] It is very important that my students learn both languages. […] During mother tongue lessons, they do so by reading, writing, talking and meeting others. They discuss and adapt the language, increase vocabulary by talking about different things. […] During mother tongue lessons, we try to learn to write and read correctly. […] We work with books. With younger students I work on reading and reading comprehension or on the writing of a simple book.”(HLT3) “I try to divide students into different groups. that is, those who are beginners and then those who know a lot of L1. We teach the entire spectrum. Students who know nothing and then those who have recently moved from L1 Country. […] We also teach preschool students [and up to] students who are in 9th grade.” (HLT 13) |

| Study guidance: Promote L2 CALP in other subjects through the use of L1. If L2 language and L2 school culture differ from L1 and L1 country -> introduce students to L2 school culture. | “You cannot just expose students to Swedish only and give them lots and lots of Swedish words and Swedish exercises. You must go through their mother tongue.” (HLT8) “Because the criteria and requirements for reaching a grade are different here than in L1-Country.” (HLT1) “There is a big difference between schools there and here.” (HLT1) | |

| Teaching basic reading and writing to students at pre-reading stages | Learning how to read and write, even among older students. Reasons why older students do not read and write yet must be investigated. Possible reasons: Students who have not attended school before, due to migration or different school traditions; Students who did not learn to read and write in their L1 due to oppression; The families’ SES and parents’ previous educational background influence the students’ learning pace. | HLT 12: “We started with basic reading and writing.” Interviewer: “You mean with preschool students?” HLT 12: “No, not only. There are also older students who cannot read and write. For example, they have not gone to school in their home country. So, they are older than their Swedish classmates. One student I’m working with right now is in fifth grade. But they can be even older.” “He has never gone to school in his L1. He spent years in refugee camps, where he went to Religion schools in another language than his L1. A language with another alphabet than his L1 and Swedish.” (HLT 12) “We couldn’t learn to read and write in L1 in our home countries. We had to learn to read and write in the home country’s official language.” (HLT5) “In L1 Country you are not forced to go to school.” (HLT 12) “I regularly talk to the parents. […] Some of them don’t have an education themselves. For instance, one mother was illiterate when she came to Sweden. So, it’s not easy for her to deal with [her daughter’s school] problems or tell the teacher what the problem is. She just says, I’m really worried about my daughter.” (HLT6) |

| Assessing and supporting students with SEN | Assessing HL teachers are experts on their students’ L1 and home culture. Comparing L1 and L2. | “A SEN teacher contacted me about a student. They suspected dyslexia and wanted me to confirm or exclude it, considering the student’s L1 proficiency.” (HLT 9) “I contribute to linguistic assessments by answering questions about the students L1. I compare their L2 development to their L1 development.” (HLT3) |

| Supporting HL teachers are dependent on the SEN teachers’ collaboration and information to support multilingual students with SEN. Not all HL teachers are informed by the SEN teachers or some HL teachers only partially. | HLT 6: “I taught a student once who had difficulties, learning difficulties. […] when I heard from the SEN teacher that she [the student] should either go to a school for pupils with intellectual disabilities or they should adapt their teaching methods to the student’s needs. I contacted the SEN teacher and asked if I could get some advice on how I should work with the student.” Interviewer: “Did you get any good tips?” HLT 6: “Yes, we shouldn’t read and write too much. But, when I asked what the student had, they only said difficulties. They did not want to specify what kind of difficulties.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roux Sparreskog, C.; Dylman, A.S. Promoting Reading and Writing Development Among Multilingual Students in Need of Special Educational Support: Collaboration Between Heritage Language Teachers and Special Educational Needs Teachers. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081016

Roux Sparreskog C, Dylman AS. Promoting Reading and Writing Development Among Multilingual Students in Need of Special Educational Support: Collaboration Between Heritage Language Teachers and Special Educational Needs Teachers. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(8):1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081016

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoux Sparreskog, Christa, and Alexandra S. Dylman. 2025. "Promoting Reading and Writing Development Among Multilingual Students in Need of Special Educational Support: Collaboration Between Heritage Language Teachers and Special Educational Needs Teachers" Education Sciences 15, no. 8: 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081016

APA StyleRoux Sparreskog, C., & Dylman, A. S. (2025). Promoting Reading and Writing Development Among Multilingual Students in Need of Special Educational Support: Collaboration Between Heritage Language Teachers and Special Educational Needs Teachers. Education Sciences, 15(8), 1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15081016