Out-of-Field Teaching in Craft Education as a Part of Early STEM: The Situation at German Elementary Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What level of professionalisation do teachers who teach craft education at elementary schools in the federal states mentioned have?

- Are there differences in the level of professionalisation between the individual federal states?

- What are the reasons that lead craft education teachers to teach out of their field?

2. Technical Education as Part of STEM Education at Elementary Schools in Germany

3. Out-of-Field Teaching in STEM Education

- (1)

- Teachers who are professionally qualified in the field of technology, though not necessarily in elementary schools, are to be sought.This group comprises teachers who have studied a technical or related subject for secondary education, but who have not received specific training for teaching technology in elementary schools. To illustrate, one may consider educators specialising in labour studies, Wirtschaft-Arbeit-Technik (WAT), or technology who were trained for secondary schools. For instance, this includes a teacher who studied Wirtschaft-Arbeit-Technik (consolidation of the subject’s economics, labour, and technology) for secondary levels and now teaches craft education in elementary schools without having undergone specific pedagogical skills training for this level.

- (2)

- Secondly, the subject of this investigation is elementary school teachers who do not possess specific training in craft education.These teachers have completed a degree in elementary school education and studied various subjects (e.g., maths or art) with a focus on elementary school didactics. However, it is evident that they lack subject-specific pedagogical skills training in the domain of craft education or technology. To illustrate this point, one may consider the case of an elementary school teacher who, as part of their teacher training programme, pursued a course of study in general studies, devoid of a particular emphasis on technical or practical work. Notwithstanding this, they provide instruction in craft education due to the absence of teachers with specialist training at their school.

4. State of Research

5. Methodology

5.1. Hypotheses

5.2. Study Design

5.3. Instrument

5.4. Sample

5.5. Data Analysis

6. Results

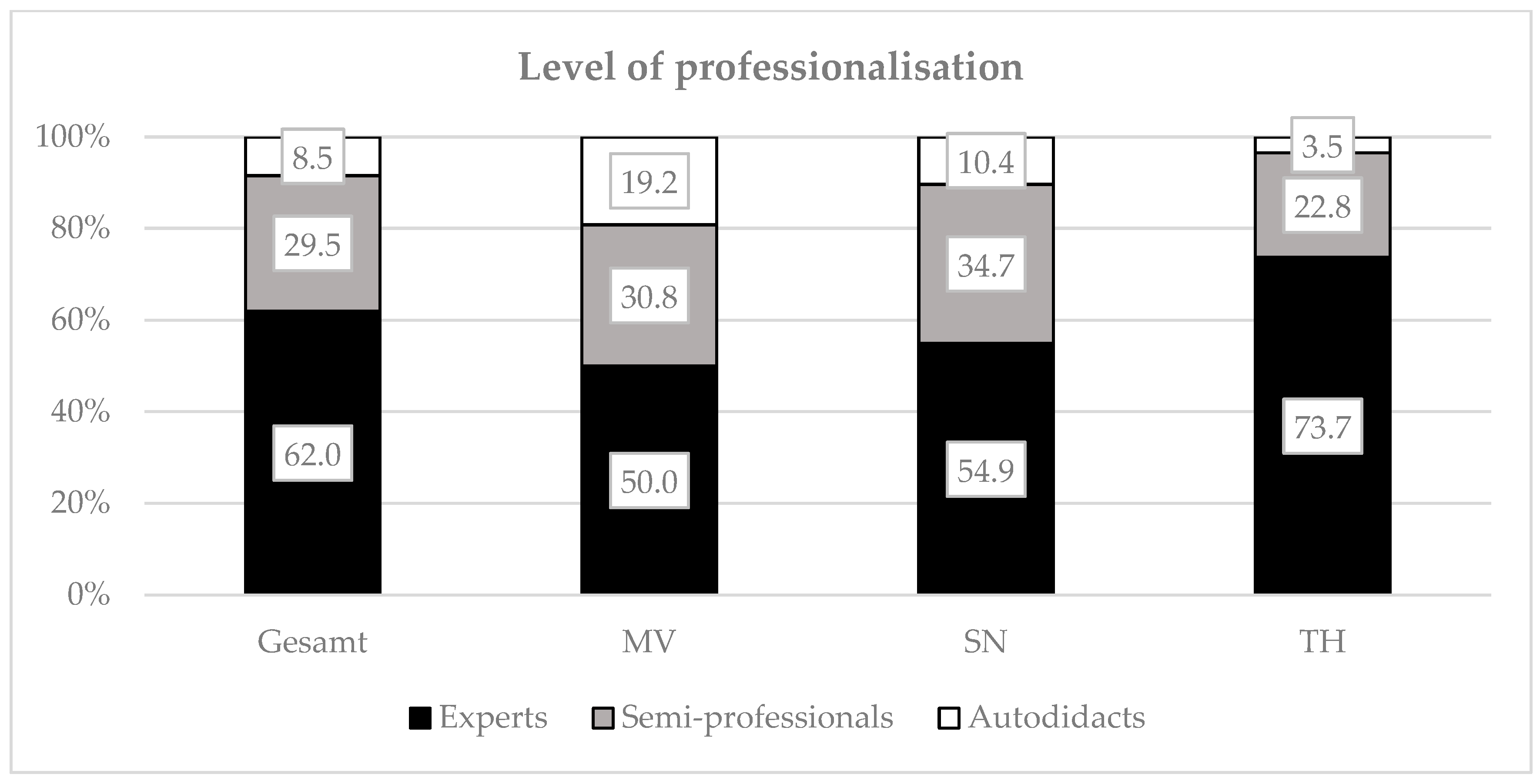

6.1. Level of Professionalisation

6.2. Differences Between the Federal States

6.3. Reasons for the Deployment of Out-of-Field Teachers in Craft Education

7. Discussion

8. Limitation

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bauer, D., Jarausch, K., Knoll, S., & Mikutta, A. (2021). Forschen und gestalten als leitprinzip im fach werken: Perspektiven für eine zeitgemäße und zukunftsorientierte fachdidaktik. In M. Müller, & S. Schumann (Eds.), Technische bildung: Stimmen aus forschung, lehre und praxis (pp. 141–160). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Baumert, J., & Kunter, M. (2011). Das kompetenzmodell von COACTIV. In M. Kunter, J. Baumert, W. Blum, U. Klusmann, S. Krauss, & M. Neubrand (Eds.), Professionelle kompetenzen von lehrkräften. Ergebnisse des forschungsprogrammes COACTIV (pp. 29–53). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Beutin, J., Arndt, M., Neumann, L., & Blumenthal, S. (2023). Fachfremdes Unterrichten im Werkunterricht. Zur Situation an sächsischen Grundschulen. BzL—Beiträge zur Lehrerinnen- und Lehrerbildung, 41(3), 420–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutin, J., & Dunker, N. (2023). Kompetenzorientierung in den rahmenplänen des sachunterrichts—Eine komparative, qualitative vergleichsanalyse. GDSU-Journal, 14, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bosse, M., & Törner, G. (2015). Teacher identity as a theoretical framework for researching out-of-field teaching mathematics teachers. In C. Bernack-Schüler, R. Erens, A. Eichler, & T. Leuders (Eds.), Views and beliefs in mathematics education: Contributions of the 19th MAVI conference (pp. 1–14). Springer Spektrum. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Erziehungswissenschaft (DGfE). (2017). Stellungnahme zur einstellung von personen ohne erforderliche qualifikation als lehrkräfte in grundschulen (seiten- und quereinsteiger). Available online: https://www.dgfe.de/fileadmin/OrdnerRedakteure/Sektionen/Sek05_SchPaed/GFPP/2017_Stellungnahme.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- de Vries, M. (2019). Technology education in the context of STEM education. In A. F. Koch, S. Kruse, & P. Labudde (Eds.), Zur bedeutung der technischen bildung in fächerverbünden (pp. 43–52). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, N., & Bortz, J. (2016). Forschungsmethoden und evaluation in den sozial- und humanwissenschaften. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- du Plessis, A. E. (2013). Understanding the out-of-field teaching experience. A thesis submitted for the degree of doctor of philosophy at the university of Queensland. Available online: http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:330372/s4245616_phd_submission.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2022).

- du Plessis, A. E., Gillies, R. M., & Carroll, A. (2014). Out-of-field teaching and professional development: A transnational investigation across Australia and South Africa. International Journal of Educational Research, 66, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskey, T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammel, L. (2011). Selbstkonzepte fachfremd unterrichtender musiklehrerinnen und musiklehrer an grundschulen: Eine grounded-theory-studie. LIT. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, L. (2013). Teaching out-of-field as a boundary-crossing event: Factors shaping teacher identity. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 11(2), 271–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, L., & Porsch, R. (2021). Teaching out-of-field: Challenges for teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 44(5), 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft (IW) (Ed.). (2023, November). MINT-herbstreport 2023. Available online: https://mintzukunftschaffen.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/MINT-Herbstreport_2023_Versandfassung_30_10_2023.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft (IW) & Bayerisches Forschungsinstitut für Digitale Transformation (bidt). (2022). Fachkräftemangel im MINT-bereich hoch. Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Available online: https://www.bidt.digital/themenmonitor/fachkraeftemangel-im-mint-bereich-hoch (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Keller, J. P., Koch, A. F., Umbricht, S., Kruse, S., Haselhofer, M., & Zimmermann, J. (2018). Erfolgsfaktoren allgemeiner technischer bildung. Ein projekt des schwerpunktthemas EDUNAT. Ausführlicher abschlussbericht. Available online: https://www.pedocs.de/frontdoor.php?source_opus=16172 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Keller-Schneider, M., Arslan, E., & Hericks, U. (2016). Berufseinstieg nach Quereinstiegs- oder Regelstudium—Unterschiede in der Wahrnehmung und Bearbeitung von Berufsanforderungen. Lehrerbildung auf dem Prüfstand, 9(1), 50–75. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, A. F., Kruse, S., & Labudde, P. (2019). Chancen und herausforderungen von technik in fächerverbünden. In A. Koch, S. Kruse, & P. Labudde (Eds.), Zur bedeutung der technischen bildung in fächerverbünden. Springer Spektrum. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckartz, U. (2018). Qualitative inhaltsanalyse. methoden, praxis, computerunterstützung (4. Aufl.). Beltz Juventa. [Google Scholar]

- Kultusministerkonferenz (KMK). (2010). Ländergemeinsame inhaltliche Anforderungen für die Fachwissenschaften und fachdidaktiken in der Lehrerbildung. Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2008/2008_10_16-Fachprofile-Lehrerbildung.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Kultusministerkonferenz (KMK). (2021). Empfehlungen der kultusministerkonferenz zur stärkung des lehramtsstudiums in mangelfächern. Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2021/2021_12_09-Lehrkraefte-Mangelfaecher.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- Kultusministerkonferenz (KMK). (2022). Gemeinsame leitlinien der länder zur deckung des lehrkräftebedarfs. Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2022/2022_10_07-Bericht-Leitlinien-Deckung-Lehrkraeftebedarf.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Landtag MV. (2019). Lehrkräfte ohne lehrbefähigung für die fächer sport, musik sowie kunst und gestaltung. Available online: https://www.dokumentation.landtag-mv.de/parldok/dokument/44558/lehrkraefte_ohne_lehrbefaehigung_fuer_die_faecher_sport_musik_sowie_kunst_und_gestaltung.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Lange, V. (2018). Politische bildung in der schule—Ein statusbericht. Ergebnisse einer bundesweiten befragung der kultusministerien. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung. Available online: https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/studienfoerderung/14033.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Lebeaume, J. (2011). Between technology education and science education: A necessary positioning. In M. J. de Vries (Ed.), Positioning technology education in the curriculum (pp. 75–86). SensePublishers. [Google Scholar]

- Lehrervorbereitungsdienstverordnung (LehVDVO M-V). (2013). Verordnung zum vorbereitungsdienst und zur zweiten staatsprüfung für lehrämter an den schulen im lande mecklenburg-vorpommern. Available online: https://www.landesrecht-mv.de/bsmv/document/jlr-LehrVorbDVMV2013pG2 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Ministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Kultur Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (MV). (2013). Rahmenplan grundschule: Werken. Available online: https://www.bildung-mv.de/export/sites/bildungsserver/.galleries/dokumente/unterricht/rahmenplaene/rp-werken-gs.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Porsch, R. (2016). Fachfremd unterrichten in Deutschland: Definition—Verbreitung—Auswirkungen. Die Deutsche Schule, 108(1), 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Porsch, R. (2020). Mathematik fachfremd unterrichten. In R. Porsch, & B. Rösken-Winter (Eds.), Professionelles handeln im fachfremd erteilten Mathematikunterricht: Empirische befunde und Fortbilungskonzepte (pp. 3–26). Springer Spektrum. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsch, R., & Wendt, H. (2015). Welche rolle spielt der studienschwerpunkt von sachunterrichtslehrkräften für ihre selbstwirksamkeit und die leistungen ihrer schülerinnen und schüler? In H. Wendt, T. Stubbe, K. Schwippert, & W. Bos (Eds.), IGLU & TIMSS. 10 Jahre international vergleichende schulleistungsforschung in der grundschule. Vertiefende analysen zu IGLU und TIMSS 2001 bis 2011 (pp. 161–183). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Renn, O., Duddeck, H., Menzel, R., Holtfrerich, C.-L., Lucas, K., Fischer, W., Allmendinger, J., Klocke, F., & Pfennig, U. (2012). Stellungnahmen und empfehlungen zur MINT-bildung in Deutschland auf der basis einer europäischen vergleichsstudie. Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften (BBAW). [Google Scholar]

- Richter, D., Engelbert, M., Böhme, K., Haag, N., Hannighofer, J., Reimers, H., Roppelt, A., Weirich, S., Pant, H. A., & Stanat, P. (2012). Anlage und durchführung des ländervergleichs. In P. Stanat, H. A. Pant, K. Böhme, & D. Richter (Eds.), Kompetenzen von schülerinnen und schülern am ende der vierten jahrgangsstufe in den fächern deutsch und mathematik. Ergebnisse des IQB-Ländervergleichs 2011 (pp. 85–102). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, D., Kuhl, P., Haag, N., & Pant, H. A. (2013). Aspekte der aus- und fortbildung von mathematik- und naturwissenschaftslehrkräften im ländervergleich. In H. A. Pant, P. Stanat, U. Schroeders, A. Roppelt, T. Siegle, & C. Pöhlmann (Eds.), IQB-ländervergleich 2012. Mathematische und naturwissenschaftliche kompetenzen am ende der sekundarstufe I (pp. 367–390). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Rjosk, C., Hoffmann, L., Richter, D., Marx, A., & Gresch, C. (2017). Qualifikation von Lehrkräften und Einschätzungen zum gemeinsamen unterricht von kindern mit und kindern ohne sonderpädagogischen förderbedarf. In P. Stanat, S. Schipolowski, C. Rjosk, S. Weirich, & N. Haag (Eds.), IQB-Bildungstrend 2016. Kompetenzen in den fächern deutsch und mathematik am ende der 4. Jahrgangsstufe im zweiten ländervergleich (pp. 335–353). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Sächsisches Staatsministerium für Kultus (SN). (2019). Lehrplan grundschule: Werken. Available online: https://www.schulportal.sachsen.de/lplandb/lehrplan/73 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Schiefele, U. (2009). Situational and individual interest. In K. R. Wentzel, & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 197–222). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Schiefele, U., & Schaffner, E. (2015). Teacher interests, mastery goals, and self-efficacy as predictors of instructional practices and student motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 42, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellisch, C. (2020). Instrumente für eine inklusive schulentwicklung. Verlag Barbara Budrich. [Google Scholar]

- Thüringer Ministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Kultur (TH). (2010). Lehrplan grundschule: Werken. Available online: https://www.schulportal-thueringen.de/media/detail?tspi=1269 (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Törner, G., & Törner, A. (2012). Underqualified math teachers or out-of-field-teaching in mathematics—A neglectable field of action? In W. Blum, R. Borromeo Ferri, & K. Maaß (Eds.), Mathematikunterricht im Kontext von Realität, Kultur und Lehrerprofessionalität (pp. 196–206). Vieweg+Teubner Verlag. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Overschelde, J. P. (2022). Value-lost: The hidden cost of teacher misassignment. In L. Hobbs, & R. Porsch (Eds.), Out-of-field teaching across teaching disciplines and contexts (pp. 49–70). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VDI & IW (Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft). (2024, August 14). Massiver fachkräftemangel in den ingenieur- und informatikberufen: Jährlicher wertschöpfungsverlust liegt bei bis zu 13 milliarden euro. VDI. Available online: https://www.vdi.de/news/detail/massiver-fachkraeftemangel-in-den-ingenieur-und-informatikberufen-jaehrlicher-wertschoepfungsverlust-liegt-bei-bis-zu-13-milliarden-euro (accessed on 22 January 2025).

| Variable | Characterisation | Percent | Absolute |

|---|---|---|---|

| Federal state | MV | 9.2 | 26 |

| SN | 50.7 | 144 | |

| TH | 40.1 | 114 | |

| Gender | Female | 85.9 | 244 |

| Male | 14.1 | 40 | |

| Age | <30 years | 16.9 | 48 |

| 31–40 years | 19.4 | 55 | |

| 41–50 years | 15.8 | 45 | |

| 51–60 years | 36.3 | 103 | |

| >60 years | 11.6 | 33 | |

| Sponsorship | Public | 94.4 | 268 |

| Private | 4.9 | 14 | |

| not specified | 0.7 | 2 | |

| School-leaving certificate | A-levels | 56.7 | 161 |

| max. entrance qualification for universities of applied sciences | 40.5 | 115 | |

| not specified | 2.8 | 8 |

| Category | Code Distribution | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Teacher shortage | 66 (53.7%) | There are not enough qualified teachers for the subject of craft education at our school. For this reason, years 1 and 2 are taught outside of the subject. |

| Interest and pleasure in the subject | 18 (14.6%) | I am enthusiastic about craft education activities and enjoy teaching craft education, especially in grades 1 and 2. |

| Previous experience/training partially available | 11 (8.9%) | I have passed the 1st state examination in the subject of works. |

| Allocation by the school leadership | 9 (7.3%) | I don’t know, especially as I said in my application that I don’t think I’m good at craft education. I’ve been a craft education teacher since my first day of teaching. |

| Creativity/ Craftsmanship | 7 (5.7%) | Because I have experience in teaching at elementary school and I am skilful and creative. |

| Completed further/ advanced training | 6 (4.9%) | Qualification with self-initiative with the specialist manager, various further training courses |

| Class teacher principle | 4 (3.3%) | […] at elementary school, all “minor subjects” must also be taught outside the subject area. |

| Voluntariness | 2 (1.6%) | I made myself available voluntarily. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beutin, J.; Arndt, M.; Blumenthal, S. Out-of-Field Teaching in Craft Education as a Part of Early STEM: The Situation at German Elementary Schools. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070926

Beutin J, Arndt M, Blumenthal S. Out-of-Field Teaching in Craft Education as a Part of Early STEM: The Situation at German Elementary Schools. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):926. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070926

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeutin, Johanna, Mona Arndt, and Stefan Blumenthal. 2025. "Out-of-Field Teaching in Craft Education as a Part of Early STEM: The Situation at German Elementary Schools" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070926

APA StyleBeutin, J., Arndt, M., & Blumenthal, S. (2025). Out-of-Field Teaching in Craft Education as a Part of Early STEM: The Situation at German Elementary Schools. Education Sciences, 15(7), 926. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070926