1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly disrupted higher education, catalyzing a rapid shift toward online, hybrid, and blended modes of delivery (

Pregowska et al., 2021). Instructors have had to reconsider the traditional pedagogies and adopt more flexible, student-centered strategies to maintain engagement and support diverse learners (

Otto et al., 2024). In Taiwan, this shift has occurred alongside broader institutional transformations, as universities adapt to pandemic-related challenges while responding to long-term trends in technology, labor market demands, and student expectations (

S.-L. Lin et al., 2021;

Xu, 2024).

These shifts underscore the urgent need to redesign learning environments so that they are both technologically responsive and aligned with the students’ evolving career needs (

Crew & Märtins, 2023;

Zuo, 2022). Scholars such as

Ajani (

2024) and

Babalola and Kolawole (

2021) have emphasized that post-pandemic curricular reform should extend beyond digital transition, embedding employability-focused competencies and adaptive skillsets within instructional models. Blended and cooperative pedagogies in particular have shown promise in fostering student engagement, collaboration, and workplace readiness (

Gudoniene et al., 2025;

Imran et al., 2023;

Ntim et al., 2021;

Vo et al., 2017).

In Taiwan, the urgency for such pedagogical innovation is compounded by demographic and economic shifts. Labor statistics from the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics indicated a modest decline in unemployment (3.34%) and labor force participation (59.20%) (

DGBAS, 2024). However, these figures also reflect the persistent labor shortages across industries, largely driven by Taiwan’s rapidly declining birthrate and its cascading effects on both the labor workforce and university enrollments (

Chiang et al., 2025). Private higher education institutions in particular face pressure to retain students while preparing students for an increasingly automated, dynamic workplace (

Hou & Lu, 2024). Within this context, vocational and technological universities are expected to serve as “practical and applied talent incubators,” helping students to transition more effectively from classroom to career (

Lin & Yang, 2025).

While numerous studies have examined career education in higher education (

Hughes et al., 2016), few have investigated how career development curricula can be redesigned using blended and cooperative learning strategies, especially in applied university contexts dealing with structural disruptions. Students in technical programs often experience career uncertainty, compounded by the rapid pace of technological change and shifting workforce expectations (

M.-H. Lin et al., 2016;

McDiarmid & Zhao, 2022;

Seow et al., 2019).

Lau et al. (

2021) argue that blended career education programs can be optimized further by accounting for emotional regulation and personality-based learning differences, especially in East Asian contexts.

To address these challenges, this study presents a redesigned career development course offered at a science and technology university in Taiwan. Grounded in the principles of blended learning, cooperative pedagogy, and experiential instruction, the course integrates online and in-person teaching strategies, real-world case studies, industry guest lectures, and collaborative student group projects. The course was initially transitioned from in-person to online delivery in response to the pandemic, allowing for a timely assessment of how technology-enhanced instruction and cooperative strategies influence student engagement and perceived learning outcomes.

More specifically, the study aims to (1) examine how the specific elements of blended and cooperative instructional design affect student–teacher interaction and engagement, and (2) explore the students’ perceptions of how the redesigned curriculum influence their learning effectiveness and career preparation.

Overall, this research contributes to the ongoing discourse on curriculum innovation in post-pandemic higher education. By capturing the students’ reflective experiences and analyzing the role of structured collaborative tasks and experiential learning, the study offers evidence-based insights for educators and curriculum designers. The findings are particularly relevant in applied university settings that seek to promote employability and engagement through pedagogical renewal in increasingly hybrid learning environments.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Blended Learning in Higher Education

2.1.1. Foundations and Pre-Pandemic Adoption of Blended Learning

Blended learning has long been recognized as a promising pedagogical model in higher education, aiming to bridge the gap between traditional face-to-face instruction and emerging digital learning modalities. It integrates the strengths of online platforms, such as flexibility, scalability, and resource diversity, with the interpersonal richness of classroom interaction (

M.-H. Lin et al., 2016). In Taiwan, blended learning began to gain traction even before the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in vocational and technological universities wherein instructors sought to address learner diversity, engagement gaps, and instructional inefficiencies through technology-enhanced strategies (

Chen & Chiou, 2014;

S.-L. Lin et al., 2021).

Educators in these institutions implemented blended models as a response to both pedagogical and logistical needs. For instance, asynchronous video lectures allowed students to review technical content at their own pace, while synchronous workshops facilitated hands-on learning and real-time feedback. This approach was consistent with constructivist theories of learning, emphasizing student autonomy, collaboration, and problem-solving as central to knowledge construction (

Ntim et al., 2021). Despite its early adoption, blended learning remained unevenly implemented, often relying on instructor initiative rather than institutional policy.

Furthermore, prior research highlights the importance of aligning instructional design with students’ learning preferences and cognitive needs.

Pregowska et al. (

2021) noted that student engagement and satisfaction in blended environments were significantly influenced by the course organization, technological familiarity, and instructor presence. These findings underscore the need for an intentional design which does not just consider technology use but also fosters meaningful learning experiences.

2.1.2. Post-Pandemic Acceleration and Evidence of Effectiveness

The COVID-19 pandemic marked a turning point in the adoption and institutionalization of blended learning. As campuses closed and physical gatherings were restricted, higher education institutions were compelled to adopt remote teaching tools on an unprecedented scale. In Taiwan, this shift was particularly critical for the applied universities that relied heavily on experiential and practice-based instruction (

Mok & Montgomery, 2021). The pandemic revealed both the resilience and fragility of the existing teaching systems and accelerated calls for more integrated, flexible course designs (

Otto et al., 2024).

Ajani’s (

2024) review of African higher education during the pandemic reflected a global pattern; digital divides, institutional unpreparedness, and the need for curriculum redesign emerged as the dominant challenges. The Taiwanese context, while more digitally developed, still experienced inequities in student access and engagement, particularly during the transition between online and hybrid formats. The current study responds to these challenges by offering a blended course model that integrates flipped learning, collaborative digital tools, and structured group tasks.

Empirical support for the effectiveness of blended learning continues to grow. A meta-analysis by

Vo et al. (

2017) across 51 studies confirmed that blended formats outperform traditional classroom instruction, particularly in the Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) and applied fields. These findings reinforce the decision to adopt a hybrid instructional strategy in the redesigned course.

Table 1 outlines the key components of this blended model, including asynchronous pre-recorded lectures, online collaboration tools, and synchronous peer interaction, all geared toward improving student engagement and career readiness.

Additionally, the recent work by

Yoosefdoost et al. (

2023a) emphasizes the importance of design nuances in blended environments. While students valued pre-recorded materials for flexibility, they also reported digital fatigue and preferred real-time interaction for critical thinking and doubt clarification. This highlights the need for balance; leveraging both live and recorded formats to maximize learning without overwhelming the students. Furthermore,

Ntim et al. (

2021) proposed a Complex Adaptive Blended Learning framework that aligns well with these findings. Grounded in constructivist and inquiry-based learning theories, the framework encourages the integration of collaborative, self-regulated, and inquiry-driven learning. These principles informed the structure of the present course redesign, which emphasized peer interaction, real-world relevance, and reflective learning.

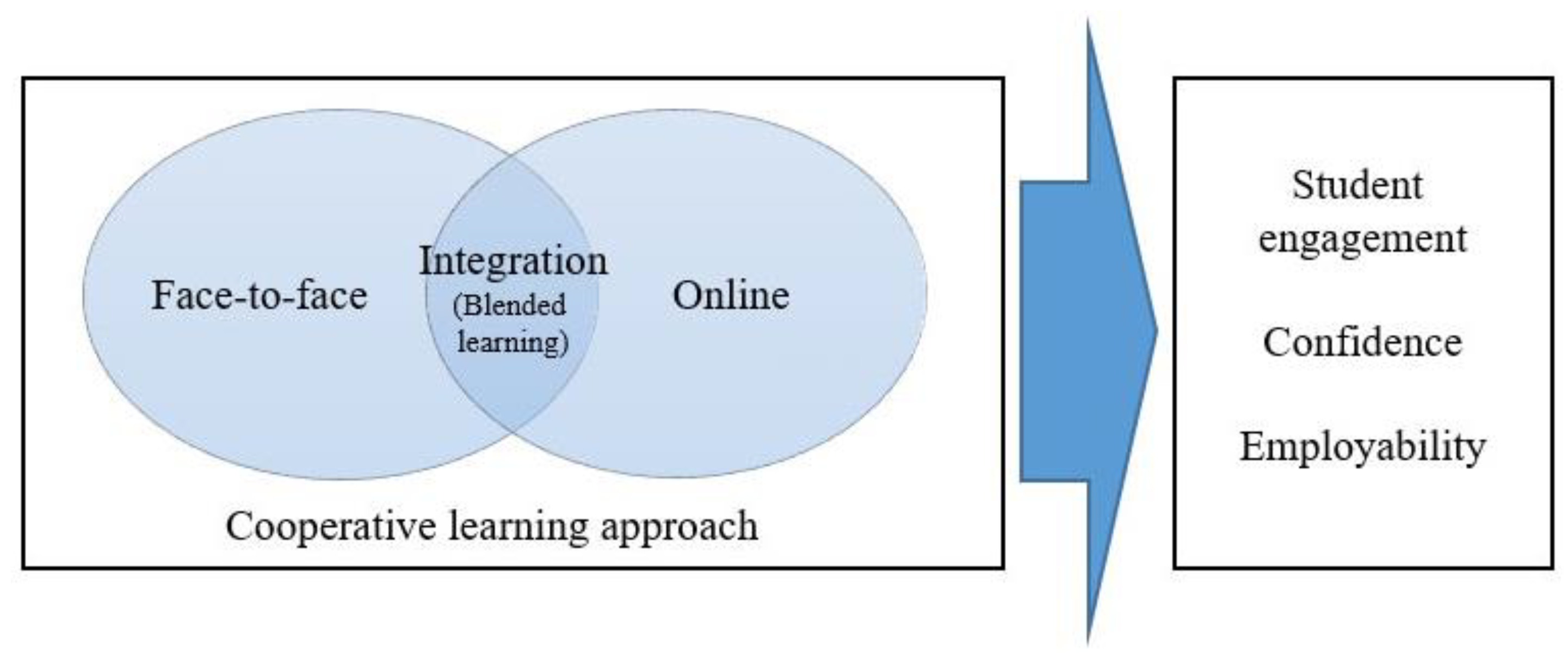

Overall,

Figure 1 summarizes the components of blended learning underpinning this study and illustrates how blended delivery modes and cooperative pedagogy jointly contribute to student engagement, confidence, and employability. By building on pre-pandemic insights while integrating post-pandemic innovations, the current study offers an evidence-based, context-specific contribution to the literature on blended learning in higher education.

2.2. Cooperative Learning Approach

Cooperative learning is a structured instructional approach wherein students work together in small interdependent groups to achieve shared academic goals while being individually accountable (

Johnson & Johnson, 2008). Unlike unstructured group work, cooperative learning emphasizes purposeful design, clear task roles, and assessment strategies that cultivate peer interaction, negotiation, and mutual support. Its conceptual foundation lies in social interdependence theory, which suggests that students achieve higher motivation, critical thinking, and retention when learning is organized around positive interdependence (

Gillies, 2016;

Slavin, 1994).

In the context of higher education, cooperative learning has been shown to significantly improve engagement, cognitive outcomes, and essential soft skills such as teamwork, communication, and leadership (

Kyndt et al., 2013;

Laal & Ghodsi, 2012). These outcomes are particularly important in career-oriented courses, where real-world problem-solving, collaboration, and reflective practice are necessary to simulate workplace dynamics (

Robbins & Hoggan, 2019). Cooperative strategies such as role assignments, peer evaluation, group decision-making, and joint presentations provide opportunities for the students to rehearse professional behavior and build confidence in their interpersonal capabilities.

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, cooperative learning has also taken on new importance within blended and online instructional formats. Research by

Ntim et al. (

2021) and

Yoosefdoost et al. (

2023b) highlights the compatibility of cooperative methods with blended learning environments, particularly in promoting inquiry-based learning, reciprocal feedback, and academic integrity. The integration of cooperative learning into hybrid formats has been shown to mitigate online disengagement and to foster digital collaboration skills, both of which are vital for post-pandemic educational resilience and employability development.

Moreover, these strategies align with the national objectives in Taiwan’s technological and vocational education system, which emphasize applied learning and graduate readiness for rapidly evolving industries (

Chiang et al., 2025;

W.-B. Lin & Yang, 2025). Through activities such as group-based career simulations, peer mock interviews, and collaborative case analyses, students are able to bridge classroom learning with real-world application. The structured components of cooperative learning, such as positive interdependence, individual accountability, and group reflection, closely mirror workplace expectations and are essential for nurturing transferable job-ready skills. These key elements are summarized in

Table 2, which outlines their instructional significance and practical relevance to career education in higher education.

2.3. Career Education and Employability Skills in Post-Pandemic Higher Education

Career education has become a central pillar of higher education policy and curriculum reform in recent decades, driven by the growing imperative to prepare students for complex, uncertain, and rapidly changing labor markets (

Hughes et al., 2016;

Kieu et al., 2023). This urgency has been magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted traditional career pathways and highlighted the need for flexible, future-oriented educational experiences (

McDiarmid & Zhao, 2022;

Zuo, 2022). Institutions are now expected not only to deliver academic content, but also to embed employability traits such as adaptability, communication, problem-solving, and self-regulation into the curriculum design (

Crew & Märtins, 2023;

Nguyen et al., 2023).

In this regard, the integration of career development courses into general education and professional curricula, especially in technological and vocational universities, has become an important strategy to bridge the gap between classroom learning and labor market expectations (

Hou & Lu, 2024;

M.-H. Lin et al., 2016). These courses often include activities such as job shadowing, interview simulations, site visits, reflective journals, and industry guest talks, all of which aim to enhance students’ practical knowledge and professional identity formation.

Studies conducted in Asian contexts, such as

Lau et al. (

2021), show that blended or synchronous career education models can significantly influence the students’ vocational identities, especially when learning is personalized to account for individual traits and emotional needs. Similarly,

Babalola and Kolawole (

2021) emphasize the importance of redesigning the curricula to incorporate post-COVID employability skills, such as digital fluency, entrepreneurial thinking, and emotional resilience; traits that have become increasingly critical in a volatile job market.

In Taiwan, career readiness is further shaped by macroeconomic and demographic changes, including an aging population, declining university enrollments, and shifts in the technological sector (

Chiang et al., 2025). These contextual factors reinforce the role of applied universities in fostering both hard and soft skills that align with national industry needs. Career education in this setting must therefore be flexible, experiential, and embedded within broader pedagogical innovations like blended and cooperative learning.

Table 3 summarizes the major frameworks and typologies of employability skills drawn from the recent literature. It maps how key traits such as adaptability, teamwork, self-efficacy, and reflective thinking are developed through integrative learning strategies. These competencies form the foundation of career-oriented education and serve as critical mediators between instructional design and labor market outcomes.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

This study adopts a qualitative, single-case research design grounded in practitioner inquiry, focusing on a single bounded case: a redesigned career development course implemented at a science and technology university in Taiwan. According to

Yin (

2018), a case study is appropriate when a researcher seeks to explore contemporary phenomena within real-life contexts, especially when the boundaries between the phenomenon and the context are not clearly evident. In this study, the “case” is defined as the design, delivery, and learning experiences of the students enrolled on the course during a single academic semester. The case is bounded by several dimensions: the course itself (i.e., “Career Development and Analysis”), the instructional strategies employed (e.g., blended learning, cooperative group work, interactive technologies), and the participating cohort (94 students, with 16 involved in in-depth interviews). This bounded approach enables a focused exploration of how specific pedagogical innovations influence student engagement and career readiness within a vocational education context.

The instructional design of the course integrated blended learning, cooperative learning, and case-based teaching. The latter, drawing from the prior literature (

Duffy et al., 2023;

Ulvik et al., 2022;

Vedi & Dulloo, 2021), involves the use of real-life cases to promote reflective thinking, decision-making, and problem-solving under the guidance of the instructor. These strategies supported the course’s overarching goal of preparing the students for internships, career planning, and real-world workplace transitions. More importantly, the researcher also served as the course instructor, which allowed for direct observations and access to the student’s reflections and learning artifacts. This approach is consistent with practitioner-based educational research (

Lytle & Cochran-Smith, 1992), where the aim is to evaluate and refine pedagogical practices through systematic reflection and analysis. The study took place during the post-pandemic transition to hybrid learning formats and responded to institutional efforts to improve student engagement and employability.

3.2. Context and Participants

The current study was conducted during the spring semester of 2021 at a science and technology university in Northern Taiwan. The course, titled “Career Development and Analysis”, was a required subject for junior-level students in the Department of Applied Foreign Languages. A total of 94 students were enrolled on the course, consisting of 88 juniors and four seniors (32 males and 62 females). The instructor—also the researcher—holds a professional certification as a Career Development Analyst, which supported the pedagogical and professional relevance of the course content. The course spanned 18 weeks, with two instructional hours per week. In the first 12 weeks, the course was conducted face-to-face; however, beginning in Week 13, due to pandemic-related restrictions, it transitioned to a fully online format using Microsoft Teams and the university’s LMS. To evaluate the students’ experiences and perceptions, 16 students volunteered and consented to participate in the follow-up interviews. Selection criteria included gender balance, group roles, and observed levels of participation, with the goal of capturing diverse perspectives. Sampling continued until thematic saturation was reached, with no new themes emerging after the 14th interview (

Braun & Clarke, 2021). All participants provided informed consent, and pseudonyms were assigned to ensure anonymity.

Table 4 shows that the sample comprised 10 male and six female students, ranging in age from 20 to 22 years, with most in their junior year and a few in their senior year of study. The majority of participants were from Taiwan, with two international students from Indonesia and Ukraine, respectively.

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

This study employed a qualitative case study methodology with multiple sources of data to ensure credibility, depth, and contextual richness (

Ahmed, 2024). The use of multiple data sources enabled a triangulation strategy to cross-validate findings and enhance the trustworthiness of the analysis (

Patton, 1999;

Yin, 2018). Data collection occurred throughout the semester, beginning in the initial weeks and continuing through to the post-course evaluation.

The primary data sources included the following:

Self-reflective logs written by students after key learning activities;

Group worksheets completed during cooperative learning sessions;

Student assignments and projects, including mock interviews and career plans;

Field notes and classroom observations recorded by the instructor;

Semi-structured individual interviews lasting 20–40 min, conducted at the end of the semester with the 16 volunteer participants;

Classroom discussions conducted at the end of the course.

The course design included both face-to-face and online components, utilizing digital tools such as the institutional LMS, Google Docs, Meet, and Jamboard. These tools supported peer interaction, formative feedback, and project-based collaboration. Each data type served a unique purpose in capturing the students’ experiences and perceptions of the course’s design and pedagogical strategies. The semi-structured interviews were conducted in two rounds: the first focused on the participants’ prior educational and work experiences, while the second explored their reflections on the interactive teaching design, the collaborative learning activities, and the perceived impact on their career preparedness. Interviews lasted between 20 and 40 min, and multiple interviews were conducted with most participants to deepen the thematic insights.

To analyze the data, a summative qualitative content analysis approach was used (

Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). This involved identifying and quantifying the key words and expressions, followed by an interpretation of the underlying meanings and thematic patterns. A primarily inductive coding strategy was applied, enabling the codes and categories to emerge from the data rather than being imposed a priori (

Elo & Kyngäs, 2008). The process included the following:

Defining the unit of analysis (e.g., statements, reflections, group work);

Generating open codes across multiple transcripts and documents;

Organizing codes into subcategories and major themes;

Comparing data sources through triangulation;

Validating interpretations through reflective memos and peer feedback.

This rigorous and iterative process allowed for the discovery of themes related to student engagement, teacher–student interaction, reflective learning, and career readiness. Data were coded manually and reviewed multiple times to ensure consistency and reliability.

To guide the semi-structured interviews and classroom discussions, a set of open-ended questions was developed to explore the students’ backgrounds, expectations, and reflections on the course. The first round of interviews focused on the participants’ previous experiences with career-related courses and any relevant work exposure, as well as their expectations upon entering the course. In the second round, the questions were designed to elicit the students’ perceptions of the course design, including the impact of cooperative group work, the effectiveness of blended learning strategies, and the role of teacher–student interaction in supporting their learning. Participants were also asked how specific activities, such as mock interviews, case studies, or the use of online platforms affected their engagement and preparedness for future career opportunities. These guiding questions helped to structure the interviews while allowing for flexibility and the emergence of unanticipated insights.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Participation was voluntary, and all students provided informed consent prior to their inclusion in the interviews and qualitative analysis. No personal identifying information was collected, and all names presented in the results are pseudonyms. Importantly, this study was conducted as part of the routine course instruction within an established university curriculum. All activities including interviews, worksheets, and reflections were integral to the course and would have taken place regardless of the research intent. As such, no experimental procedures were introduced. In accordance with the institutional guidelines for classroom-based inquiry, a formal IRB review was not required.

4. Results

4.1. Theme 1: Strengthened Student–Teacher Interaction Through Collaborative Group Work

Students widely reported that the use of collaborative group activities, supported by structured prompts and teacher guidance, helped to create a more engaging and responsive learning environment. Group projects such as poster creation, peer interviews, and scenario-based role plays were consistently mentioned as fostering not only interaction among peers but also greater access to and support from the instructor. Several students noted that having a clear group task made the teacher more “present” and responsive.

“During our group work, the teacher would often come around, ask questions, and give suggestions. It made the class feel more alive, not like just another lecture.”

—Kelly (Group 7, junior, Taiwan), reflective log

“We learned how to solve problems together. Sometimes our ideas clashed, but our teacher gave us space to think, not just give the answer.”

—Yu (Group 3, junior, Taiwan), group worksheet

“I liked how our instructor didn’t just talk. She really listened when our group was confused, especially in the Debono Six Hats activity.”

—Ellen (Group 13, junior, Taiwan), interview

However, not all students viewed the group interactions positively. A few expressed difficulty in participating equally or feeling overlooked by the teacher during some sessions:

“Sometimes I felt the teacher was only focusing on the louder groups. Our group didn’t talk much, so maybe we got skipped?”

—Xiaoli (Group 12, junior, Taiwan), interview

“It was okay, but if your groupmates are lazy, it’s hard to really learn.”

—Brian (Group 5, junior, Taiwan), open response log

These comments highlight both the enabling and limiting dynamics of teacher facilitation in a group-based learning structure. While most students experienced more dynamic engagement and teacher feedback, a minority expressed concerns about unequal participation and visibility, underscoring the importance of inclusive facilitation strategies.

4.2. Theme 2: Enhanced Self-Efficacy via Simulated Interviews

Students widely described the simulated interviews as one of the most impactful elements of the course. This activity, which required students to prepare a curriculum vitae, dress professionally, and participate in mock interviews with their peers and faculty, was consistently cited as a turning point for building career confidence and communication skills.

“I had never done anything like a mock interview before. I was nervous at first, but after the practice, I realized I could actually speak clearly and answer confidently.”

—Simon (Group 6, junior, Taiwan), interview

“It was the first time I wore business clothes for something school-related. It felt serious, and I felt like a real applicant, not just a student.”

—Sherry (Group 2, senior, Taiwan), reflective log

The hands-on nature of the interview simulation fostered a sense of self-awareness, with students recognizing both their strengths and the areas requiring improvement. Several respondents highlighted how the instructor’s constructive feedback helped them to overcome anxiety and refine their presentation style.

“After the interview, our teacher gave specific feedback. She said I needed to keep eye contact and be more concise. That really helped.”

—Moses (Group 13, junior, Taiwan), interview

“We even practiced answering tough questions like ‘Tell me about a weakness.’ I think that made us more prepared for real life.”

—Nancy (Group 8, senior, Taiwan), group worksheet

However, not all students found the experience equally empowering. A few noted challenges related to peer pressure and performance anxiety:

“When I saw others doing well, I felt more nervous. It made me doubt if I could do it as well as them.”

—Mei (Group 14, junior, Taiwan), open response

“It was helpful, yes, but some students just memorized model answers. I’m not sure if they really learned or just performed.”

—Yao (Group 4, senior, Taiwan), interview

Despite these mixed reflections, the simulated interview activity was widely seen as bridging classroom learning with real-world expectations, reinforcing the students’ belief in their own preparedness for job search situations. It also fostered an awareness of soft skills, such as poise, tone, and non-verbal communication, which are key aspects not typically emphasized in traditional lecture-based formats.

4.3. Theme 3: Increased Career Motivation Through Real-World Exposure

The inclusion of industry case studies, guest talks from alumni and human resources professionals, and site visits to partner companies emerged as key motivational factors for the students. Many participants expressed that these activities provided valuable insights into actual workplace practices, making their career goals feel more tangible and attainable.

“The site visit helped me see what an actual office looks like. Before that, I had no real idea of how people work in a company.”

—Kelly (Group 7, junior, Taiwan), interview

“Listening to alumni who graduated from our department and now have jobs really gave me hope. I started imagining myself working like them.”

—Gold (Group 15, junior, Indonesia), reflective log

These experiences also sparked more diverse career exploration. Several students reported a stronger sense of direction, noting that seeing how their field operates in practice helped to confirm or refine their career interests.

“At first, I thought I wanted to do marketing, but after the company visit, I realized I’m more interested in product design. It changed my view.”

—Brian (Group 5, junior, Taiwan), interview

“What I liked was that we didn’t just learn from the teacher, but from people actually working in the industry. It made me take my career planning more seriously.”

—Chang (Group 11, junior, Taiwan), group worksheet

However, not all students found the exposure equally beneficial. A few expressed that while the visits were informative, they lacked hands-on involvement or felt disconnected from their specific interests:

“I liked the visit, but we were just walking around. It would be better if we could do something, not just watch.”

—Yu (Group 3, junior, Taiwan), open response

“The human resource talk was useful, but some parts didn’t really relate to my major. It was too general.”

—Xiaoli (Group 12, junior, Taiwan), interview

These reflections suggest that while the experiential components enhanced motivation for many, they also need to be better tailored or scaffolded to ensure relevance across diverse student pathways. Nonetheless, the activities succeeded in making career preparation more authentic, helping the students to link the course content to their future goals.

4.4. Theme 4: Deeper Reflection Supported by Digital Tools

A notable outcome of the blended course design was the facilitation of student reflection through the use of digital tools. Weekly reflection logs, online group documents, and asynchronous platforms such as Padlet and Google Docs enabled the students to document their thoughts more thoroughly, revisit peer input, and refine their understanding of career-related concepts over time.

“Writing weekly logs helped me organize my thoughts. I realized I had changed my mind about my future job goals after reading what I wrote.”

—Mei (Group 14, junior, Taiwan), reflective log

“The online documents let us see how others think. It was different from class, where only some people talk. Here, we all shared ideas.”

—Sherry (Group 2, senior, Taiwan), interview

For many students, the asynchronous nature of the digital platforms encouraged deeper engagement by allowing time for personal processing. Compared to real-time class discussions, these tools reduced the pressure and promoted more considered responses.

“I feel shy in class, but in Padlet, I could really say what I think without being afraid.”

—Nancy (Group 8, senior, Taiwan), interview

“Sometimes you need more time to think. The online reflections gave us that chance.”

—Moses (Group 13, junior, Taiwan), group worksheet

However, a few students were less enthusiastic, citing repetition or uncertainty about the purpose of the online tasks:

“We wrote a lot, but I didn’t always understand if the teacher read them or not.”

—Shao (Group 1, junior, Taiwan), interview

“Some of the online tasks felt the same. Maybe we can have more variety next time.”

—Ian (Group 10, senior, Ukraine), open response

Despite the occasional concerns about feedback and task design, the reflective component of the course contributed meaningfully to the students’ ability to track their personal growth, articulate their career aspirations, and develop metacognitive skills. These outcomes demonstrate the potential of thoughtfully integrated digital tools to support sustained engagement beyond the classroom boundaries.

To synthesize the qualitative findings,

Table 5 presents a cross-theme summary of the four core outcomes identified in this study. Each theme is supported by evidence from multiple data sources: interviews, reflective logs, group worksheets, and classroom observations, allowing for a triangulated understanding of the student learning experiences. The table highlights how the blended and cooperative elements contributed to student–teacher interaction, self-efficacy, career motivation, and reflective practice.

5. Discussions

5.1. Linking Student–Teacher Interaction to Cooperative Pedagogy

The first major theme to emerge from the analysis was the positive shift in student–teacher interaction facilitated by the cooperative group activities. In contrast to traditional lecture-based formats, the redesigned course allowed the instructors to take on a more facilitative role, promoting inquiry, feedback, and relational engagement. This shift aligns with constructivist learning theories, where knowledge is actively co-constructed through interaction and shared experiences (

Kyndt et al., 2013;

Laal & Ghodsi, 2012). Students described feeling more seen and supported when the instructors circulated among the groups to listen, probe, and scaffold thinking. For instance,

Simon shared, “

During our group work,

the teacher would often come around,

ask questions,

and give suggestions. It made the class feel more alive,

not like just another lecture.” Similarly,

Mei emphasized how active facilitation helped to clarify roles within the group tasks: “

We learned how to solve problems together. Sometimes our ideas clashed,

but our teacher gave us space to think,

not just give the answer.”

These positive observations affirm that cooperative learning, when paired with a strategic teacher presence, can foster a more dynamic, relational classroom climate (

Robbins & Hoggan, 2019). However, not all the experiences were uniformly positive. Some students noted gaps in equitable attention, particularly among the quieter groups.

Nancy expressed, “

Sometimes I felt the teacher was only focusing on the louder groups. Our group didn’t talk much,

so maybe we got skipped?” Similarly,

Brian commented on the uneven participation: “

It was okay,

but if your groupmates are lazy,

it’s hard to really learn.” These reflections highlight a critical tone: while cooperative pedagogy strengthens interaction overall, it requires intentional scaffolding to ensure inclusivity and balanced participation. The instructor’s role in moderating group equity and identifying disengagement remains vital (

Laal & Ghodsi, 2012). This finding echoes the prior literature suggesting that effective group learning must be accompanied by teacher strategies that address group dynamics, participation anxiety, and silent voices (

Kyndt et al., 2013;

W.-B. Lin & Yang, 2025).

5.2. Enhanced Self-Efficacy via Simulated Interviews

The second theme highlighted the students’ growth in career-related self-efficacy, particularly through simulated job interviews and role playing activities embedded in the course. These experiential components provided the students with practical rehearsal spaces for real-life scenarios, helping them to manage anxiety and articulate their skills more confidently. These findings are consistent with the studies emphasizing the importance of situated learning in building learners’ self-belief (

Bandura, 1997;

Gittings et al., 2020). In particular, role play and mock interviews allowed the students to receive immediate feedback, engage in reflective learning, and observe peer strategies, thereby reinforcing their self-efficacy through vicarious experiences and mastery attempts.

Student reflections supported this interpretation.

Kelly shared, “I’ve never done an interview before this. Practicing in class, and then getting tips, really helped me imagine doing it for real”. While

Simon also noted, “At first I was nervous, but after practicing with my group and watching others, I felt more sure about what I can say”. However, not all students experienced the same level of benefit. For instance,

Mei observed that “some of the interviews felt too fast or like acting… I wish we could do more of them.” This suggests that while the activity was generally empowering, the limited time or superficial role play elements may have constrained deeper engagement for some learners. Moreover, this aligns with

Lau et al.’s (

2021) argument that emotional regulation and cultural sensitivity play a crucial role in how students internalize learning during career development courses. For Taiwanese students, who may face sociocultural barriers around assertiveness and self-promotion, scaffolded simulation exercises serve as valuable supports to bridge confidence gaps. Overall, the simulated interviews contributed meaningfully to the students’ perceived self-efficacy but also exposed the need for more personalized and repeated practice opportunities to maximize their impact.

5.3. Fostering Career Motivation Through Real-World Exposure

The integration of real-world industry exposure through site visits, guest speakers, and simulated interview activities was consistently cited by students as a pivotal factor in enhancing their career motivation. This finding supports the literature emphasizing the value of experiential and contextualized learning in strengthening vocational identity and aspiration (

Babalola & Kolawole, 2021;

Lau et al., 2021). Students noted that direct interactions with the practitioners made future career paths seem more tangible. As

Nancy reflected, “

Hearing from alumni and professionals helped me imagine what it’s really like to work in this field. I felt more motivated to prepare.” While

Ian mentioned that seeing workplace settings firsthand during the site visits made abstract job descriptions feel more concrete, “

After visiting the company,

I realized I need to improve not just my GPA,

but how I present myself.”

These activities not only provided contextual relevance but also prompted the students to reflect on their own skill gaps and future aspirations. According to career construction theory, such exposure can trigger internal dialogues and identity shifts that build motivational clarity (

Savickas, 2005). However, not all students reported an equally transformative experience. Some felt the visits were too brief or lacked direct interaction with the working professionals. For instance,

Sherry noted “

The site tour was interesting,

but it felt like a one-way presentation. I wish we could ask more questions.” This variation reflects the need for structured follow-up activities and guided debriefings to maximize the motivational impact of real-world experiences (

Gittings et al., 2020). Overall, the inclusion of authentic, workplace-oriented components helped to bridge the academic learning with future employment, enhancing the students’ sense of purpose and relevance.

5.4. Deepened Reflective Thinking Supported by Digital Tools

The final theme highlights how the integration of online tools, such as asynchronous reflective logs, collaborative platforms, and digital feedback, enabled the students to engage in more deliberate, metacognitive reflection about their learning and career paths. Compared to traditional in-class discussions, the digital tools allowed for extended thinking time, greater personalization, and the documentation of evolving perspectives. This finding supports the research showing that technology-mediated reflection can enhance students’ ability to monitor their learning processes and articulate insights over time (

Ajani, 2024;

Yoosefdoost et al., 2023a). As

Ellen explained, “

Writing weekly reflections helped me track my growth. I could go back and see how my thinking changed.”

Students also reported that using platforms like shared documents or online bulletin boards facilitated more inclusive participation, especially for those less vocal in face-to-face settings. For instance,

Xiaoli noted that “

I don’t usually speak up in class,

but writing online let me share my ideas more clearly.” This aligns with

Ntim et al.’s (

2021) finding that blended learning supports self-paced critical engagement, especially for those students balancing academic, personal, and emotional demands. Furthermore, the archivable nature of the digital contributions enabled the instructors to offer targeted feedback, which several students found encouraging and clarifying. However, a few students also noted that the reflection activities sometimes felt repetitive or lacked a clear connection to the course outcomes. As

Yu reflected, “

I wrote the reflections,

but sometimes I didn’t know if I was doing it right or if it mattered.” This suggests a need to scaffold the digital reflection tasks with clearer prompts and rubrics, while ensuring that the students are able to understand their purpose and how they contribute to the learning goals. When effectively designed, such tools can support deeper, sustained introspection and help to cultivate career-ready self-awareness.

5.5. Limitations and Reflexivity

While the study yielded valuable insights into the students’ learning experiences during the redesigned career development course, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, although data triangulation across interviews, worksheets, and reflective logs was employed to enhance credibility, the study was conducted by the course instructor, which may still introduce potential bias. In particular, no independent coder was engaged, and no formal intercoder reliability was calculated. Second, while the course drew from internationally relevant pedagogies, the setting was confined to a Taiwanese university, and cultural, institutional, or curricular differences may limit the transferability of the findings to other higher education contexts. Third, while the students reported enhanced self-efficacy and motivation, the study did not include pre/post measures or longitudinal follow-up to verify the persistence or measurable depth of such outcomes. Fourth, although the course included simulated interviews and industry exposure through guest speakers and site visits, the students still lacked direct workplace immersion. The absence of a mandatory internship or practicum component limited their ability to contextualize their learning through real-world engagement, especially in developing interpersonal communication and workplace adaptability skills. Future studies could complement the qualitative findings with quantitative or mixed-methods designs to more robustly assess the learning gains. Despite these limitations, the study offers meaningful implications for the design of student-centered, career-oriented learning experiences, particularly in contexts where hybrid, experiential, and cooperative pedagogies converge.

6. Conclusions

This study illustrates how thoughtfully redesigned career development courses combining blended learning, cooperative strategies, and experiential activities can meaningfully enhance student engagement, confidence, and career preparedness in post-pandemic higher education. Drawing from the students’ reflective logs, group work outputs, and interviews, the findings reveal that collaborative group tasks, interactive simulations, and real-world exposure helped learners to clarify goals, build communication skills, and feel more equipped to navigate professional transitions. More specifically, four key dimensions were noted: (1) strengthened student–teacher interaction through collaborative group work, (2) enhanced self-efficacy via simulated interviews, (3) increased career motivation through real-world exposure, and (4) deeper reflection supported by digital tools and structured activities. These findings show that hybrid learning models—when thoughtfully implemented—can nurture interpersonal growth, career confidence, and reflective thinking among undergraduate students navigating a volatile and rapidly changing educational landscape. These benefits were particularly visible in the development of self-efficacy and peer interdependence, both key attributes for employability in today’s dynamic job market.

By grounding this redesign in both constructivist learning theory and recent post-pandemic research on student-centered and technology-supported instruction, the study offers timely insights into how hybrid pedagogies can support institutional resilience and personalized learning. While the context was a Taiwanese university course, the teaching model and student experiences hold broader relevance for the higher education systems navigating similar transitions across Asia and beyond. Future iterations of such programs would benefit from deepened workplace integration, cross-cultural engagement, and the expanded use of English-medium instruction to foster global readiness. In addition, drawing on the reinforced learning models that integrate cooperative learning with digital ethics and academic integrity may also help to align employability goals with the demands of an AI-mediated educational environment. Likewise, pairing qualitative exploration with quantitative or longitudinal methods could offer a more robust understanding of the learning impact over time. Ultimately, this study contributes to the growing body of evidence suggesting that post-pandemic higher education requires not just a digital infrastructure, but pedagogical innovation anchored in empathy, authenticity, and student voice.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

IRB review was not required for the current study. This study was conducted as part of routine course instruction within an established university curriculum. All activities including interviews, worksheets, and reflections were integral to the course and would have taken place regardless of research intent. As such, no experimental procedures were introduced.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants gave their consent to participated in the data collection procedure.

Data Availability Statement

Most of the data transformations and analyses are contained within the article. The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to privacy and confidentiality concerns related to student participation.

Acknowledgments

In the preparation of this paper, the author used the AI-based tool Wordtune to assist with grammar correction and clarity in written expression. The tool was employed solely for linguistic refinement and did not contribute to the conceptual development, research process, analysis, or substantive content of the manuscript. The author has carefully reviewed and edited the final version to ensure that all ideas, arguments, and interpretations reflect their original intentions. The author takes full responsibility for the content and conclusions presented in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ahmed, S. K. (2024). The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajani, O. A. (2024). A systematic review of the post COVID-19 pandemic transformation on design and delivery of curriculum. Interdisciplinary Journal of Education, 7(1), 84–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, S. O., & Kolawole, C. O. O. (2021). Higher education institutions and post-COVID in-demand employability skills: Responding through curriculum that works. International Journal of Social Learning, 2(1), 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, E. (2020). Effective family engagement starts with trust. Available online: https://www.gse.harvard.edu/ideas/news/20/04/effective-family-engagement-starts-trust (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. H., & Chiou, H.-H. (2014). Learning style, sense of community and learning effectiveness in hybrid learning environment. Interactive Learning Environments, 22(4), 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.-W., Liu, Y.-Y., Shih, Y.-H., Sun, L.-C., Wang, H.-Y., & Bendraou, R. (2025). Taiwan’s adjustment measures for addressing low birthrate: A review. Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology, 9(3), 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crew, T., & Märtins, O. (2023). Students’ views and experiences of blended learning and employability in a post-pandemic context. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 8(1), 100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DGBAS (Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics). (2024). Manpower survey, May 2024. Available online: https://eng.dgbas.gov.tw/News_Content.aspx?n=4438&s=233464 (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Din, C., & MacInnis, M. (2024). Blended learning and lab reform: Self-paced SoTL and eeflecting on student learning. Papers on Postsecondary Learning and Teaching, 7, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, B., Tully, R., & Stanton, A. V. (2023). An online case-based teaching and assessment program on clinical history-taking skills and reasoning using simulated patients in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Medical Education, 23, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, R. M. (2016). Cooperative learning: Review of research and practice. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 41(3), 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittings, L., Taplin, R., & Kerr, R. (2020). Experiential learning activities in university accounting education: A systematic literature review. Journal of Accounting Education, 52, 100680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokhale, A. A. (1995). Collaborative learning enhances critical thinking. Journal of Technology Education, 7(1), 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudoniene, D., Staneviciene, E., Huet, I., Dickel, J., Dieng, D., Degroote, J., Rocio, V., Butkiene, R., & Casanova, D. (2025). Hybrid teaching and learning in higher education: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 17(2), 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haythornthwaite, C., Kazmer, M. M., Robins, J., & Shoemaker, S. (2000). Community development among distance learners: Temporal and technological dimensions. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 6(1), JCMC615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, A. Y. C., & Lu, I.-J. G. (2024). Are Taiwan private universities ready for a tsunami in the era of under-enrolment? Exploring Taiwanese private higher education in typology, regulatory framework, and emerging crisis. Journal of Asian Public Policy. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D., Mann, A., Barnes, S.-A., Baldauf, B., & McKeown, R. (2016). Careers education: International literature review. Education Endowment Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Imran, R., Fatima, A., Salem, I. E., & Allil, K. (2023). Teaching and learning delivery modes in higher education: Looking back to move forward post-COVID-19 era. The International Journal of Management Education, 21(2), 100805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (1985). Motivational processes in cooperative, competitive, and individualistic learning situations. In C. Ames, & R. Ames (Eds.), Reseaerch on motivation in education (Vol. 2, pp. 249–286). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, R. T. (2008). Social interdependence theory and cooperative learning: The teacher’s role. In R. M. Gillies, A. F. Ashman, & J. Terwel (Eds.), The teacher’s role in implementing cooperative learning in the classroom (Vol. 8, pp. 9–37). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kieu, Q. T., Kirya, M. M., & Liu, W.-T. (2023). Employment tactics and strategies of technical-vocational education students for career and professional development in the labour market of Vietnam. Journal of Technical Education and Training, 15(2), 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyndt, E., Raes, E., Lismont, B., Timmers, F., Cascallar, E., & Dochy, F. (2013). A meta-analysis of the effects of face-to-face cooperative learning. Do recent studies falsify or verify earlier findings? Educational Research Review, 10, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laal, M., & Ghodsi, S. M. (2012). Benefits of collaborative learning. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31, 486–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S. S. S., Wan, K., & Tsui, M. (2021). Evaluation of a blended career education course during the COVID-19 pandemic on students’ career awareness. Sustainability, 13(6), 3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-H., Hu, J., Tseng, M.-L., Chiu, A. S. F., & Lin, C. (2016). Sustainable development in technological and vocational higher education: Balanced scorecard measures with uncertainty. Journal of Cleaner Production, 120, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-L., Wen, T.-H., Ching, G. S., & Huang, Y.-C. (2021). Experiences and challenges of an English as a medium of instruction course in Taiwan during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 12920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, W.-B., & Yang, C.-M. (2025). Sustainable recruitment strategies in technological and vocational education: Admission scores and enrollment challenges under Taiwan’s joint registration and distribution system. Journal of Posthumanism, 5(1), 1128–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, S. L., & Cochran-Smith, M. (1992). Teacher research as a way of knowing. Harvard Educational Review, 62(4), 447–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, R., & Rennie, F. (2006). Elearning: The key concepts (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, G., & Sellen, A. (2000). The value of video in work at a distance: Addition or distraction? Behaviour & Information Technology, 19(5), 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDiarmid, G. W., & Zhao, Y. (2022). Learning for uncertainty: Teaching students how to thrive in a rapidly evolving world. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, K. H., & Montgomery, C. (2021). Remaking higher education for the post-COVID-19 era: Critical reflections on marketization, internationalization and graduate employment. Higher Education Quarterly, 75(3), 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C., & Mildenberger, T. (2021). Facilitating flexible learning by replacing classroom time with an online learning environment: A systematic review of blended learning in higher education. Educational Research Review, 34, 100394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. L., Nguyen, H. T., Nguyen, N. H., Nguyen, D. L., Nguyen, T. T. D., & Le, D. L. (2023). Factors affecting students’ career choice in economics majors in the COVID-19 post-pandemic period: A case study of a private university in Vietnam. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 8(2), 100338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntim, S., Opoku-Manu, M., & Kwarteng, A. A.-A. (2021). Post COVID-19 and the potential of blended learning in higher institutions: Exploring students and lecturers perspectives on learning outcomes in blended learning. European Journal of Education and Pedagogy, 2(6), 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S., Bertel, L. B., Lyngdorf, N. E. R., Markman, A. O., Andersen, T., & Ryberg, T. (2024). Emerging digital practices supporting student-centered learning environments in higher education: A review of literature and lessons learned from the COVID-19 pandemic. Education and Information Technologies, 29, 1673–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patton, M. Q. (1999). Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Services Research, 34(5), 1189–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Pregowska, A., Masztalerz, K., Garlińska, M., & Osial, M. (2021). A worldwide journey through distance education: From the post office to virtual, augmented and mixed realities, and education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Education Sciences, 11(3), 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, S., & Hoggan, C. (2019). Collaborative learning in higher education to improve employability: Opportunities and challenges. In M. Fedeli, V. Boffo, & C. Melcarne (Eds.), Fostering employability in adult and higher education: An international perspective (pp. 95–108). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Savickas, M. L. (2005). The theory and practice of career construction. In R. W. Lent, & S. D. Brow (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 42–70). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Saw, K. G., Majid, O., Abdul Ghani, N., Atan, H., Idrus, R. M., Rahman, Z. A., & Tan, K. E. (2008). The videoconferencing learning environment: Technology, interaction and learning intersect. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(3), 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seow, P.-S., Pan, G., & Koh, G. (2019). Examining an experiential learning approach to prepare students for the volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous (VUCA) work environment. The International Journal of Management Education, 17(1), 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sethy, S. S. (2008). Distance education in the age of globalization: An overwhelming desire towards blended learning. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 9(3), 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H. (2021). Building effective blended learning programs. In B. H. Khan, S. Affouneh, S. H. Salha, & Z. N. Khlaif (Eds.), Challenges and opportunities for the global implementation of e-learning frameworks. IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R. E. (1994). A practical guide to cooperative learning. Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Ulvik, M., Eide, H. M. K., Eide, L., Helleve, I., Jensen, V. S., Ludvigsen, K., Roness, D., & Torjussen, L. P. S. (2022). Teacher educators reflecting on case-based teaching: A collective self-study. Professional Development in Education, 48(4), 657–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedi, N., & Dulloo, P. (2021). Students’ perception and learning on case based teaching in anatomy and physiology: An e-learning approach. Journal of Advances in Medical Education & Professionalism, 9(1), 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, H. M., Zhu, C., & Diep, N. A. (2017). The effect of blended learning on student performance at course-level in higher education: A meta-analysis. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 53, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Chen, N.-S. (2009). Criteria for evaluating synchronous learning management systems: Arguments from the distance language classroom. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 22(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.-H. (2024). Declined quality? A poststructural policy analysis of the ‘quality problem’ in Taiwanese higher education. Journal of Education Policy, 39(6), 943–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagata-Lynch, L. C. (2014). Blending online asynchronous and synchronous learning. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 15(2), 189–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Yoosefdoost, A., Fantucci, H., Abu El Haija, K., & Santos, R. M. (2023a, May 17–18). Remote learning & online fatigue: Exploring the live and pre-recorded tutorials impacts on teaching effectiveness and students’ learning. Teaching and Learning Innovations Conference, Guelph, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Yoosefdoost, A., Jariwala, H., & Dos Santos, R. M. (2023b, May 17–18). Artificial intelligence, new technologies, and academic integrity concerns: A positive fightback through teaching effectiveness and rein-forced learning. Teaching and Learning Innovations Conference, Guelph, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, K. (2022). Understanding motivation, career planning, and socio-cultural adaptation difficulties as determinants of higher education institution choice decision by international students in the post-pandemic era. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 955234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).