1. Introduction

Minority-serving institutions (MSIs) in the United States are becoming increasingly crucial in expanding participation in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields (

Taylor & Wynn, 2019). Historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) have been noted for their significant contributions to graduating a disproportionately high number of Black and African American students in STEM disciplines (

Owens et al., 2012;

Taylor & Wynn, 2019;

Toldson, 2018). For example, HBCUs have a notable record of producing graduates who earn terminal degrees in science, engineering, medicine, law, and other fields (

NSTC, 2024;

Toldson, 2018). These and other factors have contributed to the increased interest of prospective students in HBCUs. During the 2023 and 2024 college admissions periods, HBCUs experienced a surge in applications, a trend that some link to the United States Supreme Court’s ruling on student admissions and growing racial tensions in the U.S. (

McLean, 2024;

National Center for Education Statistics, 2023). For example, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University saw an enrollment of 13,883 students during the 2023–2024 academic year, an increase of 400 students compared to 2022–2023 (

North Carolina A&T State University, 2023). Similarly, Howard University experienced a 10% rise in enrollment, while Bethune-Cookman University in Florida reported a 4% increase (

Central Florida Public Media, 2024). These trends indicate growth in student enrollment across various HBCUs, reflecting their continued appeal and impact. Overall, this increase has sparked discussions about the critical role of HBCUs in maintaining the nation’s global competitiveness in STEM, especially as the U.S. college-age population becomes more diverse. Discussions take various forms; for example, the 2023 HBCU STEM Undergraduate Success Center Conference and Graduate Professional Fair was held at Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia (

HBCU STEM Undergraduate Success Center, 2023). Additionally, a roundtable discussion titled “Serving Servant Leaders” took place in 2023 (

I S-STEM Hub, 2023). These events highlight ongoing efforts to engage stakeholders, foster dialog, and address critical issues within HBCUs.

It is important to note, however, that in 2022, HBCUs announced 23 leadership changes; in 2023, this number nearly doubled to 41 position changes (

Broussard & Doman, 2023). While the average tenure of chancellors and presidents has declined nationally—from 8.5 years in 2006 to only 5.9 years as of 2022 (

Herder, 2024), HBCU leaders in equivalent roles have significantly shorter tenures (approximately 3.3 years) (

Kimbrough, 2017). From a research capacity-building standpoint, many of the nation’s largest HBCUs, those classified as Carnegie R2 and R3 institutions that are making an aggressive effort to obtain R1 status (

Donastorg, 2022), are being negatively impacted by instability in the institution’s highest leadership position (

Broussard & Doman, 2023;

Fletcher et al., 2024). Moreover, leadership instability can hinder strategic planning and other long-term initiatives crucial for institutional growth and stability, such as STEM broadening participation efforts (

Nguyen et al., 2019).

Given the critical and influential role HBCUs have played for nearly 200 years in the U.S., it is essential that these institutions are equipped to meet increasing demands, including rising interest leading to higher student enrollment, expanding research in critical workforce areas (e.g., computing, cybersecurity, AI), and industry-needs for top talent (

Skinner et al., 2002;

Thang & Quang, 2005). Research indicates that leadership behaviors significantly impact employee performance (

Bass, 1985), innovation (

Burpitt & Bigoness, 1997), and organizational effectiveness (

Bass & Avolio, 1994). Organizational leadership is crucial for an institution’s ability to implement change (

S. Freeman & Palmer, 2020;

Nordin, 2012). The turnover of presidents and chancellors at HBCUs can negatively affect their ability to retain leaders and implement necessary changes to meet these demands. Further research on leadership turnover suggests that even with change strategies in place, unanticipated turnover, such as resignations or terminations, can disrupt change initiatives (

Latta & Myers, 2005). Therefore, ensuring leadership stability in executive-level roles is vital for building research capacity and achieving institutional goals.

2. Literature Review

HBCUs continue to play a significant role in broadening the participation of historically excluded individuals within STEM fields (

Owens et al., 2012;

Toldson, 2018). Due to the significant role HBCUs play, the Association of Public and Land Grant Universities (APLU) organized conferences and initiatives to cultivate innovative ideas and strategic plans to enhance the prospects of these institutions and address the challenges they encounter (

Dorn, 2013). These efforts aim to help HBCUs actualize their mission and contribute to their long-term strategic plans, including STEM broadening initiatives (

J. M. Lee & Keys, 2014).

HBCUs and administrative staff acknowledge that training is necessary for staff productivity, capacity, and retention. In addition, they attributed burnout and turnover to HBCU staff taking on multiple roles (

Candid, 2023), which contributes to problems related to securing funding because they have challenges maintaining relationships with donors (

Center for Changing Our Campus Culture, 2017). Therefore, Freeman and Palmer indicate that stakeholders’ perceptions of effective leadership strategies of HBCU presidents were related to experiential skills, including “managing finances and fundraising, business acumen, demonstrating good interpersonal skills, innovation, and working collaboratively across multiple constituencies”, and professional knowledge, such as having a keen understanding of the institution’s mission and culture (

S. Freeman & Palmer, 2020, p. 222).

Being established post-Civil War to provide education to the African Americans who were recently freed, HBCUs were not a response to a demographical shift, as an HBCU is “any historically black college or university that was established before 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of black Americans” (

U.S. Department of Education, 2020). Therefore, when an HBCU closes, it cannot be replaced with a new HBCU. Despite the seriousness of the consequences of the closure of such schools, HBCUs continue to encounter numerous challenges that have led to the closure of nearly 20 HBCUs (

Schexnider, 2017;

Suggs, 2019).

The notion of turnover refers to the voluntary departure of employees from organizations (

Price, 2001). Undeniably, turnover is problematic, disruptive, and expensive, hence alarming (

Armstrong, 2012;

Price, 2001). Voluntary turnover has both financial and moral consequences for organizations. Financially, it incurs recruitment and training costs and the risk of hiring poorly integrated employees. Morally, it leads to the overworking of the remaining employees, causing tension and affecting the social climate (

Chen, 2008). The departure of productive employees can particularly destabilize the work environment, reduce service quality, and result in the loss of expertise and achievements, increasing the learning curve for new employees (

Grissom et al., 2012;

S. Lee, 2018;

Singh & Loncar, 2010;

Tariq et al., 2013). Regarding turnover, four factors were identified: problems with interpersonal relationships, failure to meet business objectives, inability to build and lead a team, and inability to develop or adapt (

Van Velsor & Leslie, 1995).

Voluntary turnover of such a position is known as dysfunctional turnover.

Crisp (

2021) argued that dysfunctional turnover refers to the case “when valued employee desires to leave the organization, but the organization wants to retain the individual”. A university president is a high-profile position and a representative of the institution’s mission and goals (

Fisher et al., 1988). They play both functional and symbolic roles (

Harris & Ellis, 2018). This key position is instrumental in fundraising, budget management, and planning, as well as participating in and representing the institution at local, national, and federal levels and forming the connecting link between different stakeholders (

Fisher et al., 1988). “The organization of colleges and universities, the influence of the external environment, the multiple roles that presidents must play, and the constituencies they must please make it challenging for presidents to fulfill expectations” (

Eckel & Kezar, 2011). Symbolically, presidents also “are believed by others to have a coherent sense of the institution and are therefore permitted, if not expected, to articulate institutional purposes” (

Birnbaum, 1992). Therefore, the demands and expectations associated with this role place significant pressure on presidents, often leading to turnover (

Tekneipe, 2014).

Harris and Ellis (

2018) indicated that the available literature on turnover falls within two traditions. The first focuses on the organizational context, scrutinizing organizational features, including economic and environmental factors that lead to CEO turnover. The second tradition pertains to individual attributes, such as age and other personal characteristics, focusing on what individuals could not achieve, leading to their turnover, or what they lacked to perform the job efficiently, rather than considering how the job itself compromised these leaders, particularly their capitals and the resources they brought to the position (

Harris & Ellis, 2018). The literature highlights several factors influencing presidential leadership, including fundraising, competition among institutions, government regulations, political constraints, enrollment growth, and institutional rankings. Additionally, the fast pace and high demands of the role further contribute to its complexity (

American Council on Education, 2012;

Harris, 2009;

Martin & Samels, 2004;

McLaughlin, 1996). Moreover, the organizational and environmental contexts in which presidents operate create a complex set of rules that they must master and navigate effectively (

Eckel & Kezar, 2011). Challenges also arise from interactions with policymakers, board members, and faculty, whose decisions and expectations directly impact a president’s ability to lead (

American Council on Education, 2012).

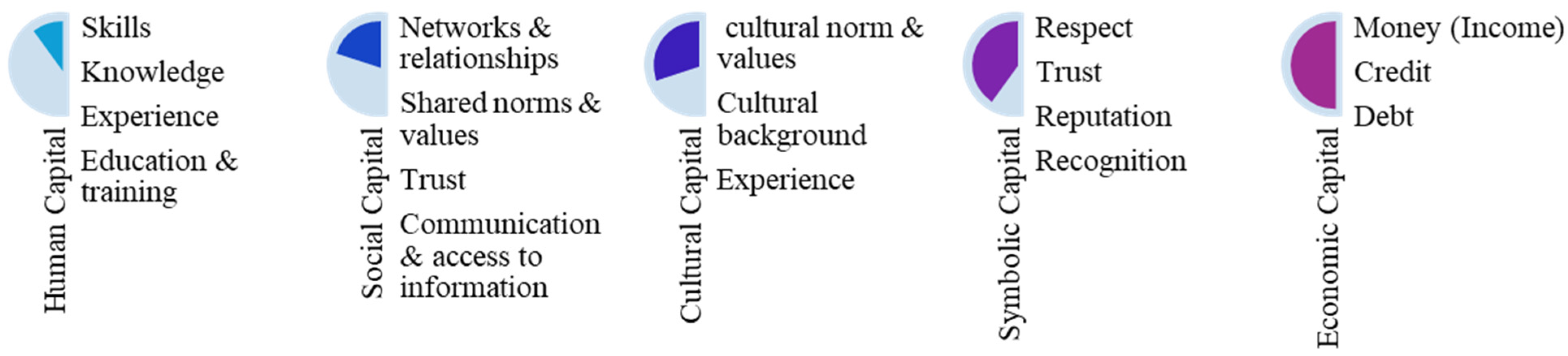

Therefore, building on both traditions, the aim of this study was twofold. First, aligning with the organizational context tradition, it aimed to identify the organizational areas linked to HBCU president and chancellor turnover, from the perspective of current external and internal HBCU stakeholders. This insight not only captured stakeholders’ perspectives but also highlighted their concerns, providing a more comprehensive understanding of their priorities and the key factors shaping their perceptions. Second, in line with the tradition of individual attributes, identifying these critical areas enabled us to determine the leaders’ capitals crucial to some of the selected areas. This helped illustrate how the personal and professional capital of leaders can be compromised, leading to turnover, and how undermining their capitals can impact STEM efforts.

4. Research Methodology

This is the first phase of a larger three-phase project. This phase is primarily quantitative, but with a mixed-methods approach, incorporating a qualitative element through the open-ended question (i.e., What do you think can be done to address President/Chancellor turnover at HBCUs? Is there anything else you’d like to add?). The purpose of the quantitative part was to address the following research questions: (1) What are the most pivotal organizational areas affected by the turnover of HBCU presidents and chancellors, as perceived by current HBCU stakeholders, to significantly impact long-term critical areas linked to sustainability for the institutions? (2) What are the factors leading to frequent president turnover? (3) How do these factors impact presidents themselves and their forms of capital leading to their resignation? These areas include institutional advancement, funding, and industry partnerships—critical to research capacity building and STEM broadening participation initiatives. In addition, we believed that identifying these critical areas enabled us to create connections between HBCU leaders’ capitals and some of the crucial identified factors. This demonstrated how compromising leaders’ capitals can result in turnover and how undermining leaders’ capital can affect ongoing efforts, particularly those related to STEM.

4.1. Target Population

The target population for this research study includes 156 current and former stakeholders of HBCUs, such as presidents and chancellors, board members, executive cabinet members (e.g., vice presidents/chancellors), faculty, staff, students, and leaders from industry and partner organizations that support and fund HBCU efforts (see

Table 1). The inclusion criteria encompass individuals who have experienced the repercussions of presidential and chancellor turnover or are invested in ensuring the success of HBCUs. To capture a diverse range of responses through the HBCU community, the survey was administered to individuals across all levels of HBCUs’ organizational structures, internal and external, to the colleges and universities.

The rationale for including current and past members of the HBCU community was to gather data that reflects the perceptions of past members regarding the impact of low turnover rates on HBCUs’ participation and research capacity-building efforts in contrast to current members who are navigating the crisis. This approach ensures a comprehensive understanding of the issue from multiple perspectives, while the research focuses on the impact on critical areas for higher education institutions, particularly STEM education.

4.2. Survey Development, Dissemination, and Analysis

A design, redesign, and review process was implemented to develop the survey using relevant research and best practices. The survey questions were developed following a thorough review of the existing literature on presidential and chancellor turnover, particularly within the context of HBCUs. The survey then underwent a review process to confirm that it accurately captures stakeholder perspectives on president and chancellor turnover at HBCUs. Experts were recruited to review the survey, and their feedback was incorporated to refine question clarity, ensure alignment with research objectives, and enhance the instrument’s overall validity. The recruited experts and researchers ensured that the survey was clear and unambiguous to minimize misinterpretation.

Questions within the survey asked participants to report their relationship with HBCUs, their current role related to HBCUs, their time affiliated with HBCUs, information about the HBCU with which they were affiliated, factors impacting president/chancellor turnover, the impact of turnover on the university, and participant demographic information. The survey consisted of Likert, open-ended, and closed-ended questions using Qualtrics. The survey respondents were asked the following two (2) Likert-scaled questions, choosing from five options: no impact (0), low impact (1), medium impact (2), high impact (3), or N/A/Do not know (excluded from analysis). The survey participants were primarily recruited at the 2023 National HBCU Week Conference in partnership with the White House Initiatives on HBCUs, where attendees were invited to participate via an official QR code displayed at event venues and circulated through conference materials. To limit the possibility of duplicated responses, the survey form enabled only one response per device login. Participation was voluntary, and the survey targeted a diverse group of stakeholders, including faculty, administrators, students, and policymakers involved in HBCUs. Survey responses were exported from Qualtrics to Excel, then imported into IBM SPSS Statistics (version 29) for analysis. Descriptive and statistical analyses, including t-tests, were conducted to assess the frequencies, means, and significance of differences among the areas of impact and the factors, and between external and internal stakeholders.

Regarding the open-ended question responses, thematic analysis was conducted to identify the most frequently occurring themes, revealing stakeholder-suggested solutions and broad perceptions of the leader turnover crisis. This approach allowed for a systematic examination of qualitative data, ensuring that patterns in stakeholder feedback were identified and interpreted in relation to the broader institutional challenges. We utilized an inductive coding approach, as themes were derived directly from the data rather than predetermined categories or themes, allowing for an organic and unbiased exploration of stakeholder perspectives. After carefully reviewing the responses, the coding process was conducted manually using Microsoft Excel software. Once initial codes were generated, similar codes were grouped to form broader themes. These themes represented stakeholder-suggested solutions and prevailing perceptions regarding the leader turnover crisis. It is worth noting that this thematic analysis does not incorporate frequency counts, as the focus is on identifying and interpreting recurring themes that highlight stakeholders’ shared viewpoints rather than quantifying them.

5. Results

The survey analysis highlighted the most impactful factors that contribute to leader turnover from the stakeholders’ perspective. The first factor was stakeholder engagement, including students, faculty, executive cabinet, and university administrators. The survey revealed the perceived impact of president/chancellor turnover at HBCUs on stakeholder engagement due to lack of leadership stability.

The findings in

Figure 3 showed that presidential turnover significantly affects student engagement, with 52% of respondents reporting an impact. Faculty engagement is also significantly impacted, with 69% reporting a high impact. University administrator-level engagement is perceived as highly impacted by turnover, with 77% indicating a high impact. However, the most affected group is the executive cabinet engagement, with approximately 79% of the respondents reporting a high impact.

The second factor negatively influenced by leader turnover is the morale and retention of stakeholders.

Figure 4 shows the perceived impact by the various stakeholders.

Figure 4 shows that leader turnover at HBCUs significantly affects morale and retention. Students’ morale and retention are slightly less affected than engagement, with 50% of respondents reporting a high impact in both areas. Faculty morale is more affected by turnover than retention, with 75% and 54% selecting high impacts, respectively. Similarly, 73% of respondents believed that the morale of university administrators is highly impacted, while 79% reported a high impact on executive/administrative morale.

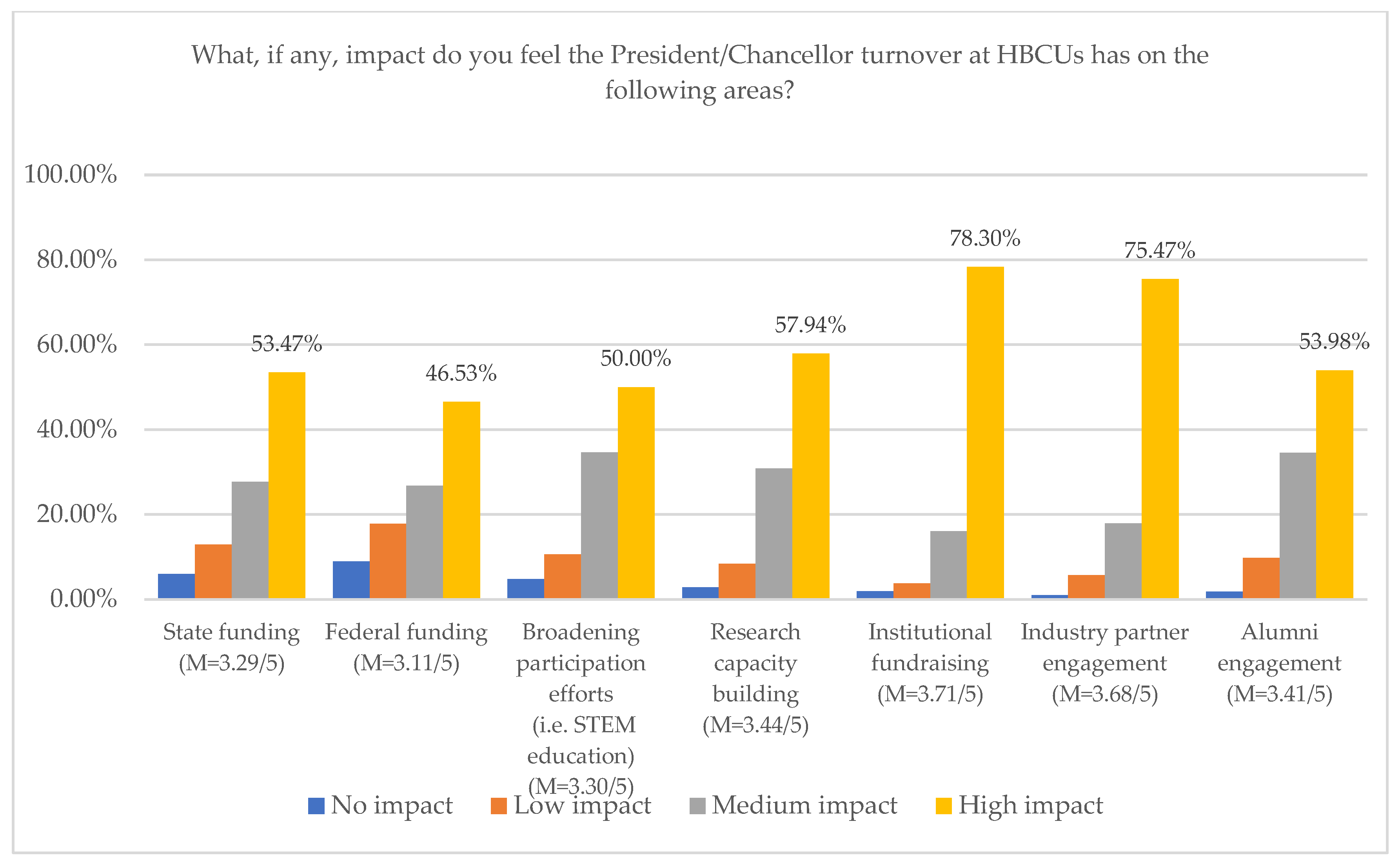

Other external factors commonly influenced by leader turnover include funding, engagement, and efforts related to broadening STEM education.

Figure 5 indicates that leader turnover significantly impacts institutional fundraising efforts, with 75.47% indicating a high impact. Other funding sources, including state and federal funding, were also affected, with 55% and 47% reporting a high impact, respectively. In addition, industry partner and alumni engagement showed high impact rates of 75% and 54%, respectively. Research capacity and efforts to broaden participation are similarly impacted, with 58% and 50% of stakeholders reporting high impacts. Overall, institutional fundraising is perceived as highly impacted, followed by industry partner engagement, while federal funding is the least impacted.

In addition, the stakeholders were also asked about the possible challenges HBCU leaders encounter in their positions. The survey also attempted to identify the possible challenges relevant to various stakeholders.

The results in

Figure 6 indicated that challenges with the board are perceived to have a high impact by 89% of all the stakeholders, making it the most significant challenge, whereas 62% of the stakeholders perceived institutional resources as highly impactful. The harsh higher-education climate is rated as having a high impact by 44%. Challenges with state-level funding have a high impact as reported by 61%. On the other hand, challenges with national funding were perceived as having a high impact by 56%. Additionally, 53% of the stakeholders reported that organizational changes highly impact leadership turnover. The financial position of the institution has a high impact as indicated by 71% of the respondents. These factors are believed to significantly influence leadership stability at HBCUs.

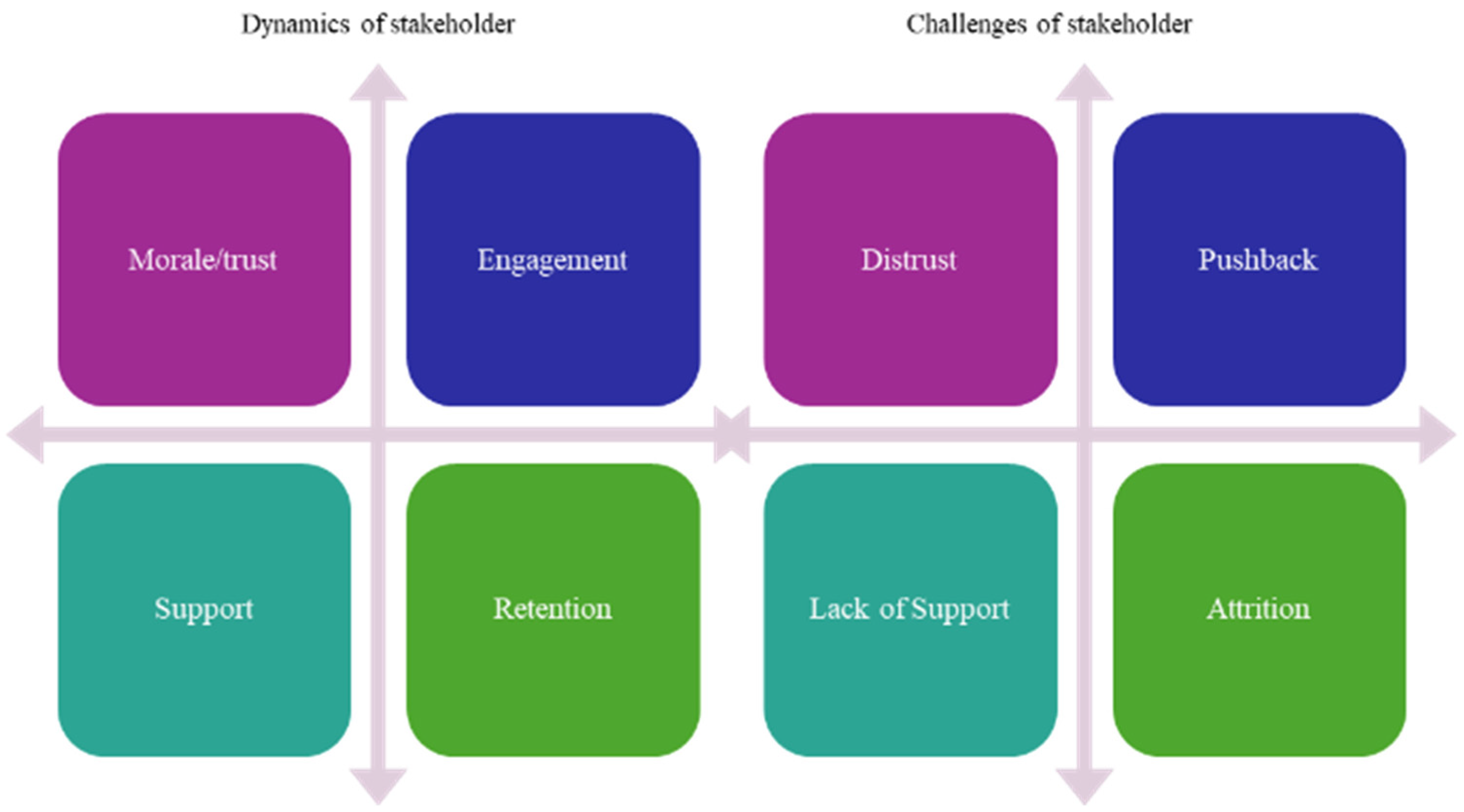

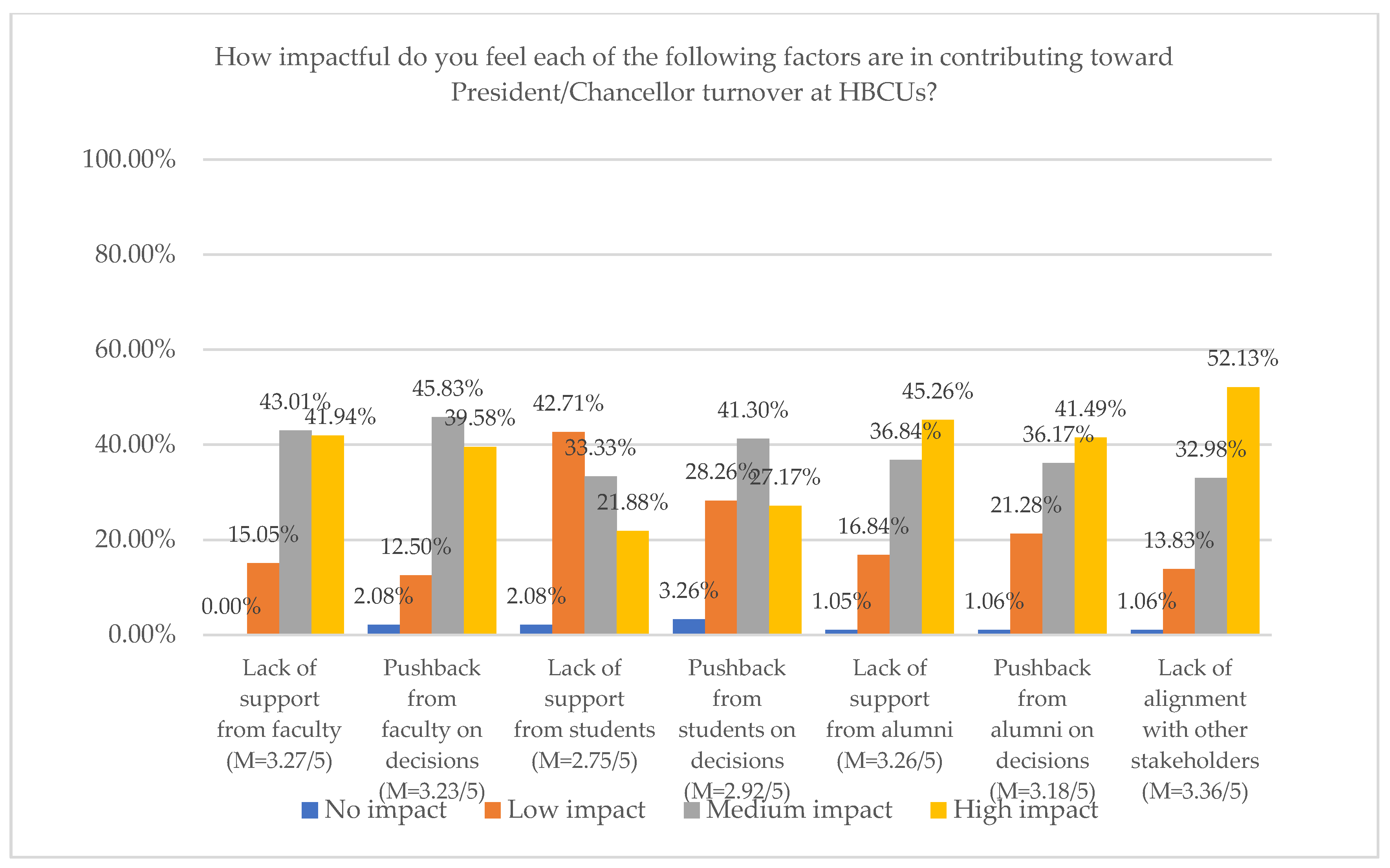

Another set of challenges is related to the dynamics necessary for the leadership to carry out their duties, support and engagement, which indicate that stakeholders trust leaders; hence, they are willing to engage and support.

Concerning pushback (or lack of engagement), in

Figure 7, pushback from faculty is perceived as highly impactful, with 40% and 45% of respondents indicating a high impact and a medium impact, respectively, followed by pushback from alumni, with 42% and 36% indicating a high and medium impact. Students’ pushback is also significant, with 36% and 45% reporting high and medium impacts, respectively. In terms of lack of support, 45% of respondents indicated that lack of support from alumni has a high impact, and 37% reported it has a medium impact. This is followed by the lack of support from faculty, with 42% and 43% reporting high and medium impacts, respectively. Interestingly, the most critical factor is the lack of alignment with other stakeholders, with 52% of respondents indicating a high impact.

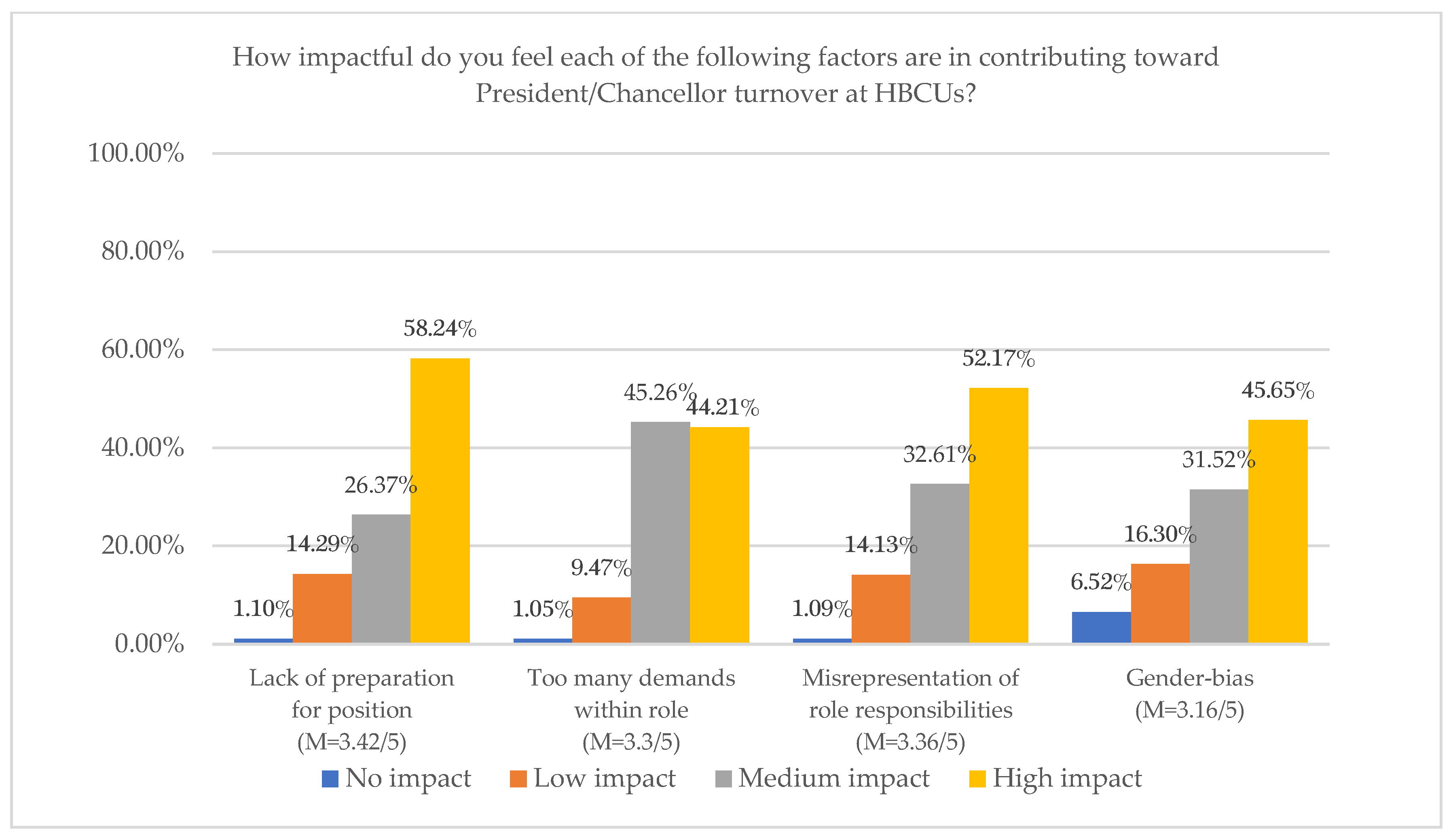

Regarding role incongruency, the results showed the impact of selected factors, including lack of preparation, excessive responsibilities within the position, misrepresentation of role responsibilities, and gender bias, on leaders’ turnover at HBCUs.

In

Figure 8, it appears that 58% and 52% of respondents believe that lack of preparation and misrepresentation of role responsibilities, respectively, are highly impactful factors contributing to leader turnover. Interestingly, 45% and 44% of stakeholders believe that excessive responsibilities within the position have a medium and high impact, respectively. Lastly, for gender bias, 35% and 45% reported that this factor has a medium and high impact on leader turnover.

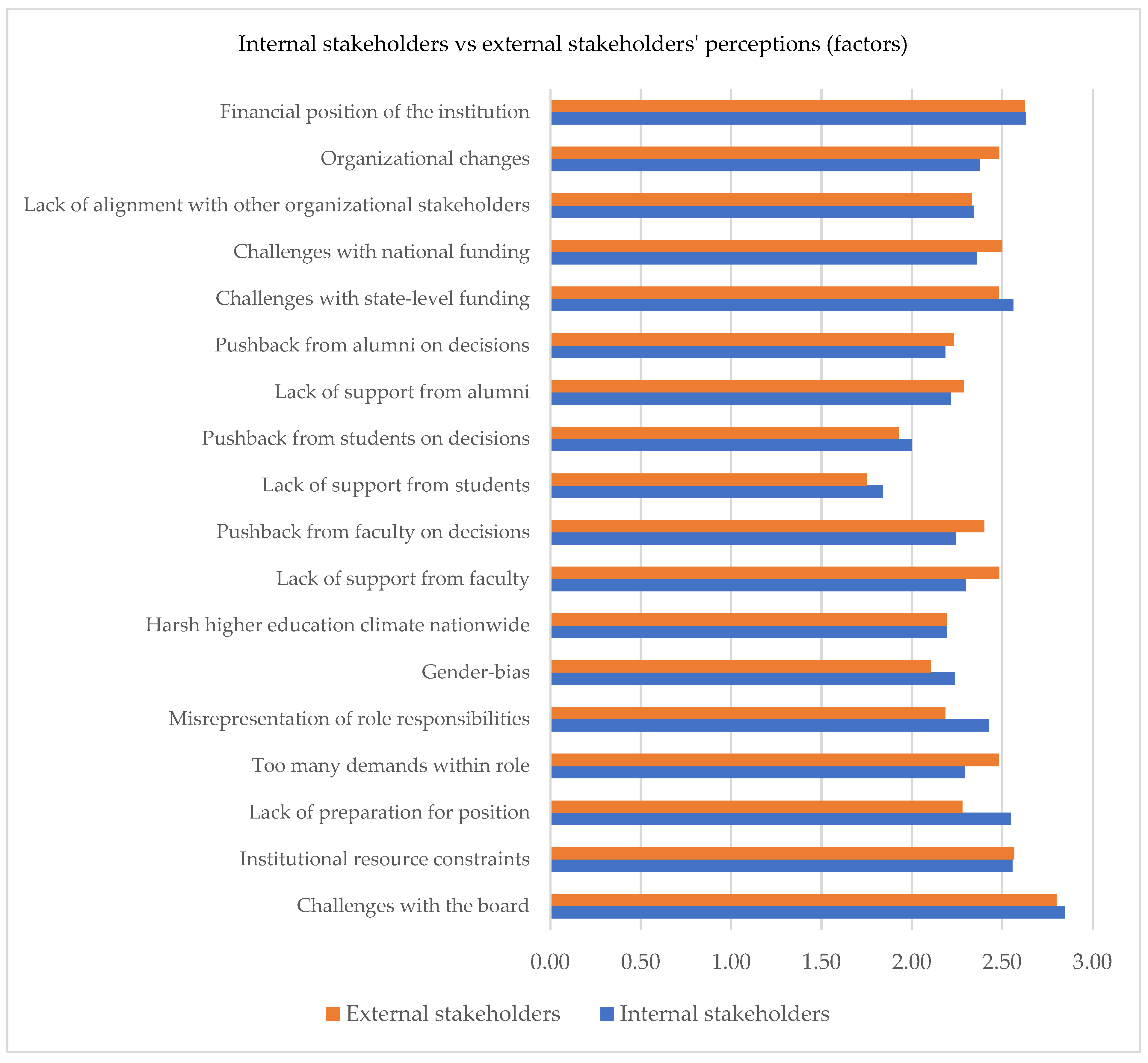

Figure 9 illustrates differences in internal and external stakeholders’ perceptions. Internal stakeholders rated faculty engagement, morale, and retention, student retention, and executive cabinet engagement higher than external stakeholders. Additionally, federal funding, institutional fundraising, and alumni engagement received higher ratings from internal stakeholders. Internal stakeholders revealed that executive cabinet, administration, and faculty engagement and morale are more affected by president turnover than students, restructuring a hierarchy that may exist on campus. This suggests that leadership and faculty experience greater challenges in adapting to institutional changes compared to students. On the other hand, external stakeholders placed higher importance on student engagement as an internal factor and state funding as an external factor, suggesting a stronger perception of student involvement and reliance on state-level financial support. Furthermore, student morale was rated slightly higher by external stakeholders. To further examine these differences, a

t-test was conducted, but the results indicated no statistically significant difference between the perceptions of internal and external stakeholders (see

Table 2). This suggests that while there are notable differences in ratings, they do not represent a substantial divergence in overall stakeholder views.

Figure 10 presents differences in internal and external stakeholders’ perceptions. Internal stakeholders rated lack of preparation for the position, misrepresentation of role responsibilities, and gender bias higher than external stakeholders, indicating concerns about leadership readiness and systemic biases within the institution. Conversely, external stakeholders rated excessive demands within the role, lack of faculty support, pushback from faculty on decisions, and challenges with national funding higher than internal stakeholders, suggesting stronger concerns about workload, institutional resistance, and financial stability. However, a

t-test conducted to further analyze these differences revealed no statistically significant difference between the perceptions of internal and external stakeholders (see

Table 3).

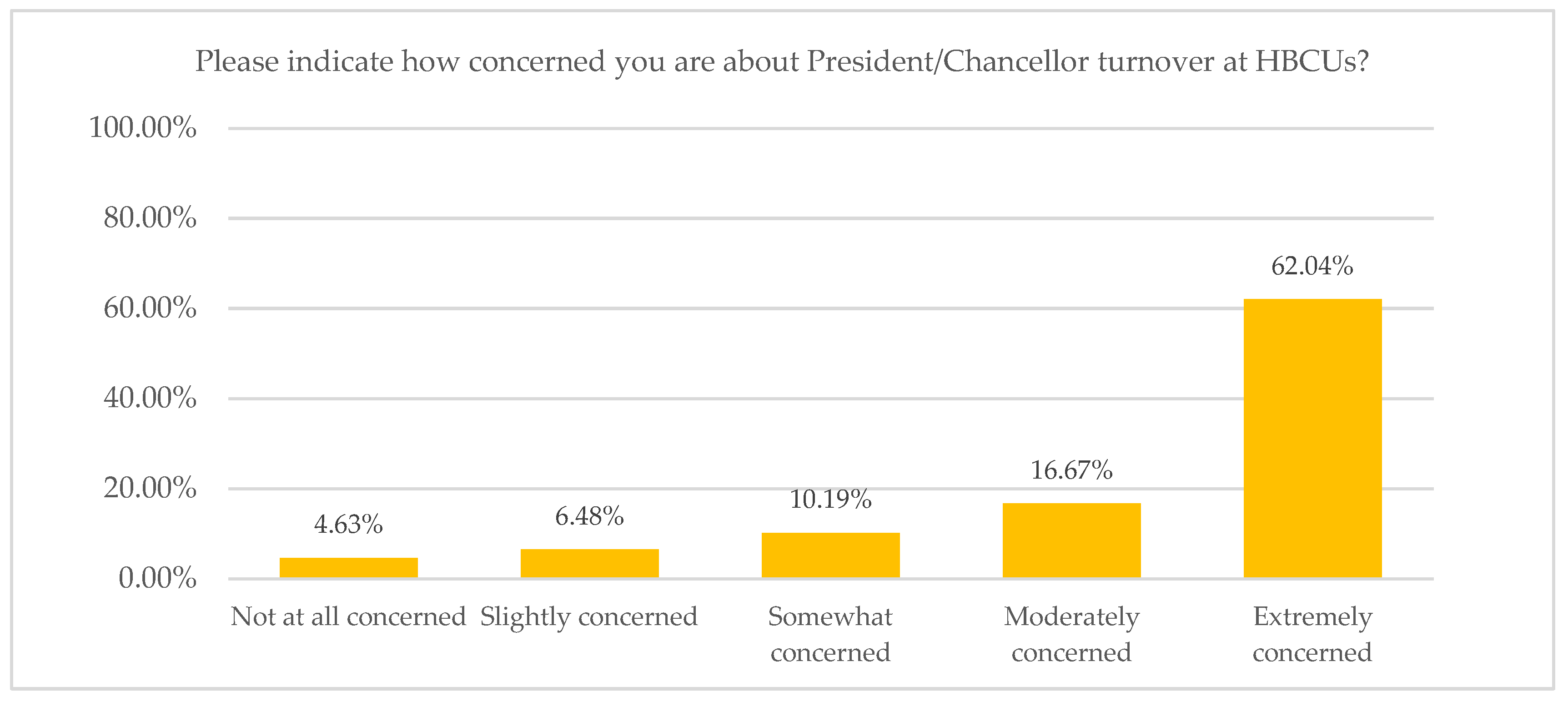

As shown in

Figure 11, stakeholders were asked about their level of concern regarding the crisis of leadership turnover. The results indicate that 62% of stakeholders are extremely concerned. On the other hand, 17% are moderately concerned, 10% are somewhat concerned, 6% are slightly concerned, and only 5% are not at all concerned.

6. Analysis

As noted earlier, the survey included an open-ended question regarding possible solutions to address the crisis of presidents turnover. The analysis revealed that internal and external stakeholders highlighted two main themes. The first theme focuses on board members’ roles, governance, and engagement. Some participants suggested “develop[ing] effective checks and balances for decisions of board members”, “improv[ing] policies on governing board appointments,” “strengthen[ing] policies of board appointments and removal,” and “training and [dividing] roles” of board members. Additionally, concerns were raised about board members being too involved in the university’s daily operations, as they “do not seem to trust leaders to do their jobs, and Black women are much more negatively impacted by this”. In response, some participants proposed “more constrainings on board members’ involvement, allowing the president to do the job they were hired for”. Furthermore, stakeholders emphasized that board member selection “need[s] to reflect the culture and student body, which should include student representatives, church representatives, higher education professionals, and civic engagement representatives”. Additionally, participants indicated that board members should be “well-versed in academics without noticeable bias against gender or education”.

The second theme focused on leadership selection, preparation, and retention. Participants expressed concerns about the appointment of presidents, with one suggesting that “[t]he selection process needs to be more focused on the goals of the organization and how the individuals’ personal and professional accomplishments fit within the needs and mission of the institution”. It was noted that “[s]election processes seem to be politically biased in many instances”. As a result, it was recommended to develop “[a] more rigorous process should be employed because it is very unfortunate to select and then have to start all over in a year. Possibly involving more stakeholders not just at the institution and board, but community leaders”. Additionally, participants emphasized the importance of vetting “candidates whose agendas, principles, and aspirations are in line with those of the institution’s goals, its well-being, and growth”. The vetting process should ensure that presidents can “meet the needs and goals of the university in their leadership role as President or Chancellor”. One participant expressed concern that HBCUs tend to hire “individual leaders who don’t have the capacity to meet the needs of the particular institution they are applying for”. Accordingly, it was recommended to “[i]mprove selection of Presidents/Chancellors, select those with strong change agent and visionary skills, [and] focus on building a positive culture among faculty and staff”.

Regarding retention, participants emphasized the importance of training, development, and support for institutional leaders. They believe that “training is needed prior to the position being filled with candidates who have some understanding of the job”. Specifically, they highlighted that presidents “need an apprenticeship-type training model to learn the intricacies of the position. They need to have an on-the-job body of knowledge, strategies, and methods of how to achieve success in an HBCU”. Participants outlined the need for training programs focused on “C-suite leadership, development of political and fundraising skills, leadership development for cabinet-level administrators, great communications/university relations staff, development of government relations (external affairs) staff, and strategic partnerships that enhance the college/university”. Additionally, they stressed the importance of clarity in job responsibilities and expectations, stating “There should be a clear delineation of the role and expectations of the President/Chancellor”. Furthermore, participants recommended that “[t]he President/Chancellor must be clear about how the Board interacts with the President”. They also emphasized that “Highly Qualified Candidates need (1) to be made fully aware of ALL challenges awaiting them at the hiring institution, (2) transparency in the level of agency they have to implement necessary changes, and (3) the full support of the board”. These findings underscore the need for structured leadership preparation, transparent governance practices, and strong institutional backing. By clarifying roles, improving the selection process, and providing targeted training and support, HBCUs can foster more effective and enduring leadership.

7. Discussion

The results highlighted what current HBCU stakeholders deem to be high-impact areas linked to HBCU president and chancellor turnover. Additionally, the perceptions of internal and external stakeholders were largely similar, demonstrating a shared understanding of the key challenges affecting leadership stability within HBCUs. Regarding stakeholder engagement, morale, and retention, leaders’ turnover significantly impacts these dynamics across various stakeholders. The executive cabinet is the most impacted, followed by faculty and university administrators. It is worth noting that an industry partner is perceived as highly impacted, almost equal to that of the executive cabinet. Student and alumni are the least impacted among stakeholders. This shows that maintaining high levels of engagement among these stakeholders, particularly those key players whose roles intersect, requires stability in leadership, as turnover is more disturbing to these groups. Other financial areas are also highly impacted, including institutional fundraising efforts, followed by industry partners, whereas the least impacted is federal funding. The results also indicated that leadership turnover significantly impacts research capacity, as leadership stability is necessary for securing research funding and creating a productive research environment. Frequent changes in leadership disturb ongoing projects and can impact other academic initiatives, especially broadening STEM participation efforts aimed at increasing diversity and inclusion in STEM fields, which require various forms of funding.

Concerning the challenges HBCU leaders encounter and must navigate, the results showed that challenges with the board are highly impactful, compromising leadership and institutional stability. This is followed by the institution’s financial position and its resource constraints, which play crucial roles in leadership management. Funding challenges at the state and national levels are perceived as influential, with state-level funding being slightly more impactful. Organizational changes are less significant, whereas the higher-education climate is viewed as least significant compared to the other factors. It is worth noting that the challenges posed by board members were reiterated in the qualitative data, with participants suggesting policies and procedures to manage board operations, appointing members, and establishing governance frameworks.

Important challenges are internal and relevant to the dynamics of leadership management and necessary to ensure the smooth implementation of strategic plans. Stakeholders perceived pushback from alumni and faculty as highly impactful, followed by student pushback. The same pattern was observed in the lack of support. The lack of support from alumni and faculty was highly impactful, followed by the lack of student support. Even though student support was less significant compared to faculty and alumni, it is still necessary for leadership stability.

Interestingly, the most critical challenge that may lead to leader turnover is the lack of alignment with other stakeholders, which is perceived as having the highest impact on leadership turnover. This may be the primary driver of turnover, as a lack of alignment can result in conflicts, resistance, and obstacles that significantly hinder leaders from making decisions and moving forward effectively. On the other hand, this may cause frustration and dissatisfaction among stakeholders, leading to misunderstandings, miscommunication, lack of trust and support, decreased morale and engagement, and eventually instability.

Regarding the role incongruency, it is obvious that ‘lack of preparation’ and ‘misrepresentation of role responsibilities’ are the most significant factors contributing to leader turnover. Therefore, development training programs and clear, accurate job descriptions are urgently needed to ensure leaders are well-equipped and to reduce frustrations and misunderstandings that can lead to turnover. In contrast, excessive responsibilities within the position and gender bias are viewed as less impactful; nevertheless, they are significant, as overloading leaders can lead to burnout, and establishing an efficient support system is necessary. Additionally, creating inclusive practices to ensure gender equality is also essential. Interestingly, this is one of the most frequently highlighted themes in the qualitative data, emphasizing the importance of preparing, training, and supporting presidents. Additionally, it underscores the necessity of providing a clear picture of what is expected in the role and the challenges involved. This repeated emphasis suggests a strong stakeholder consensus on the need for structured leadership development and appointment, as well as transparency in presidential responsibilities.

By analyzing these results and reviewing the literature and the role of the president and/or chancellor at HBCUs, our analysis found a need to understand and further explore this crisis from the perspective of a leader’s turnover crisis rather than a leadership turnover crisis. In doing so, we aligned these challenges and factors with leaders’ capitals, revealing the underlying reason for leadership turnover. In the theoretical framework, we identified the various capitals associated with leaders and the campus dynamics necessary to ensure successful leadership and effective management. However, as noted, these dynamics pose challenges when they fail to align with leaders’ expectations, causing a lack of support, distrust, pushback, and increased attrition that can hinder decision-making and progress.

Figure 12 reveals that leaders’ social, cultural, and symbolic capitals can foster stakeholders’ engagement, support, morale, and trust, cultivating retention. This, in turn, indirectly leads to fostering leaders’ capitals, which cultivates a supportive environment for effective leadership and efficient management of institutional resources and initiatives. On the other hand, challenges posed by these dynamics can negatively impact leaders’ capitals, compromising and depleting their various personal assets and resources. In more detail, leaders’ personal networks and the new networks they form with stakeholders ensure successful and effective engagement among external and internal stakeholders, creating strong connections necessary for successful leadership and management. By leveraging their social networks, leaders can build trust and gain financial support for institutional initiatives.

Concerning cultural capital, leaders utilize their values and beliefs and attempt to align them with the various stakeholders without compromising them to guarantee successful leadership and management. In addition, this alignment helps cultivate a sense of belonging among stakeholders, fostering trust, engagement, and support that leads to higher retention. On the other hand, many challenges can threaten leaders’ values and beliefs, compromising any attempt to implement inclusive practices due to a lack of alignment and support from stakeholders. Leaders’ unsuccessful attempts to foster networks, effective connections, and proper alignment with stakeholders’ values and beliefs can lead to frustration and dissatisfaction, risking leaders’ human and symbolic capitals. The importance of stakeholders is underscored by HBCU funding disparities, leading leaders to improvise “innovative solutions to address financial shortfalls…[make] difficult decisions…[and develop] alternative means to funding acquisition which may or may not be within the infrastructural capacities of the institutions” (

Lynch, 2024).

It is worth noting that the qualitative data highlighted the importance of presidents’ capital, emphasizing the need to select highly qualified individuals and provide them with comprehensive training and preparation for their roles. This reinforces the significance of leadership readiness and experience. Additionally, participants emphasized the role of board members, including their readiness, composition, and relationship with presidents, as critical factors in ensuring leadership retention and institutional stability. These results echo

Harris and Ellis (

2018), who demonstrated that turnover might be relevant to presidents’ attributes, focusing on what they lack in order to perform the job. The stakeholders’ focus on the board members reiterates existing research that emphasized the role of the challenges that arise from board members (

American Council on Education, 2012). In addition, the stakeholders recommended that new presidents need to be aware of the duties and expectations of their roles, highlighting the environmental contexts and the complex set of rules president must master and navigate effectively in the available literature (

Eckel & Kezar, 2011).

Our results align with and are supported by

McGee et al.’s (

2021) findings. They argued that HBCU leaders’ strategies for diversifying STEM include seeking off-campus opportunities for students, securing new funds for programs, building sufficient STEM infrastructure on campus, and hiring Black STEM faculty. They noted that these leaders recognize the challenges and disadvantages HBCUs face and address these issues by fostering partnerships with other HBCUs, educational institutions, relevant industries, and communities. Through these collaborations, they invest considerable effort to ensure that such partnerships directly benefit their STEM students.

Accordingly, leadership turnover in higher education, particularly in HBCUs, is partly due to the impact of leadership duties on well-being, which is a component of human capital. In these highly demanding roles, leaders draw upon and often deplete their various forms of capital. The challenges posed by campus dynamics can severely deplete and compromise their social, cultural, and symbolic capital, leading to frustration, stress, burnout, and dissatisfaction, eventually risking their economic capital. Remaining in these positions requires leaders to continuously leverage and maintain their capital. When the costs outweigh the benefits, their capitals are threatened and depleted. Therefore, voluntary turnover and resignation are common. Compromising leaders’ capitals can jeopardize long-term initiatives, including STEM broadening participation efforts. Consequently, more attention must be paid to leaders’ capital to ensure effective leadership and management and establish stability, enabling the implementation of institutions’ goals and strategic plans.

Given these findings, efforts need to be made to protect leaders’ capitals by implementing well-being and mental health support programs, encouraging a culture of work–life balance, and providing them with an effective personal support system to prevent burnout and promote overall well-being. Institutions need to ensure that campus dynamics do not turn into challenges that strain leaders’ social, cultural, and symbolic capitals. Thus, systems or programs fostering strong connections among stakeholders need to be implemented and funded, creating a culture of effective communication, team building, and inclusion. In addition, new leaders need to be mentored to ensure smooth integration with the institutions and their stakeholders, and effective alignment between their values and beliefs with those of the stakeholders to avoid miscommunication or misalignments. This successful alignment can be encouraged through inclusive and welcoming practices and environments. Institutions must pay attention to leaders’ symbolic capital, which might be at risk due to their leadership position, as it may damage their reputation, respect, and recognition. Accordingly, institutions need to ensure that this capital is protected and that the leadership position enhances it rather than damages it. Institutions need to celebrate leaders’ achievements and hard work and minimize blaming them during hard times, so they feel appreciated and respected. It is recommended to provide regular constructive feedback and evaluation, encouraging them to adjust when necessary. Finally, the benefits need to be higher than the costs. Therefore, institutions need to offer competitive salaries and benefits not only to retain qualified leaders but also to ensure their satisfaction and stability, creating a balance between challenges and threats to their capitals.

Future Work

This study surveyed HBCU stakeholders as an initial step toward understanding their perspectives and perceptions on leadership turnover at these institutions. Future research studies should include in-depth interviews and surveys with leaders, especially those who voluntarily resign, to explore the reasons and factors influencing their decisions and leading to their resignations. It is also recommended that leader turnover be further explored through longitudinal studies to better understand its long-term impact on leaders’ capitals, identify causal relationships, and develop solutions to mitigate any losses. Given the consistency in qualitative data, further investigation of board members is recommended to understand how their perceptions of presidents may influence interactions and engagement. This exploration could provide valuable insights into improving communication strategies and ensuring effective leadership support, ultimately contributing to institutional stability and governance efficiency. In addition, more studies are needed on the relationships among presidents, board members, and campus stakeholders to better understand how these dynamics affect institutional governance, leadership stability, and decision-making. Such research can provide deeper insights into strategies for fostering stronger collaboration, improving communication, and ensuring long-term leadership retention. For policymakers, comparing institutions with high leader-retention rates to those with low retention rates may uncover factors and governance structures that influence leader retention and inform effective policy development.