Self-Concept Modulates Motivation and Learning Strategies in Higher Education: Comparison According to Sex

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Objectives and Hypotheses

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

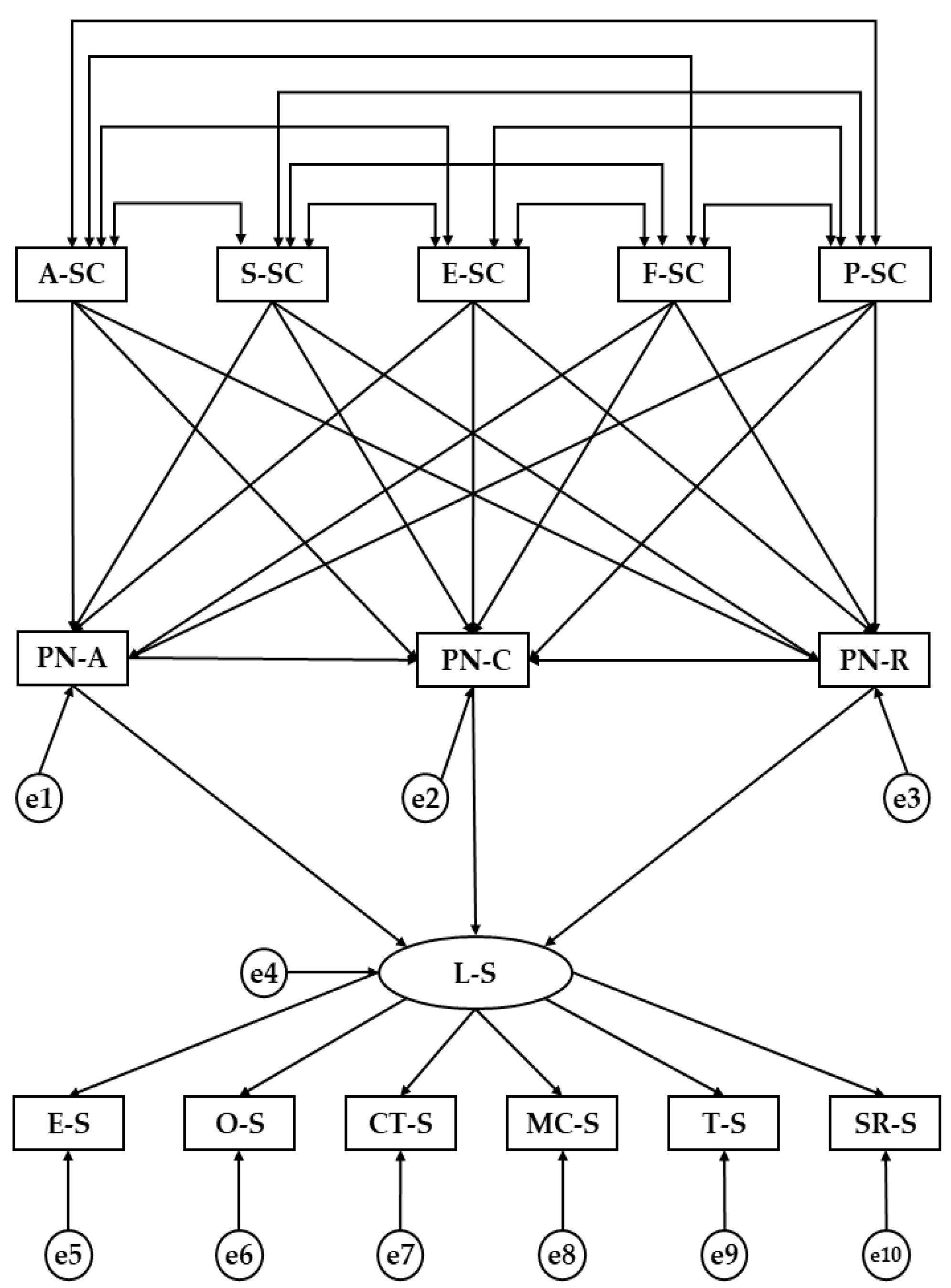

2.4. Data Analysis

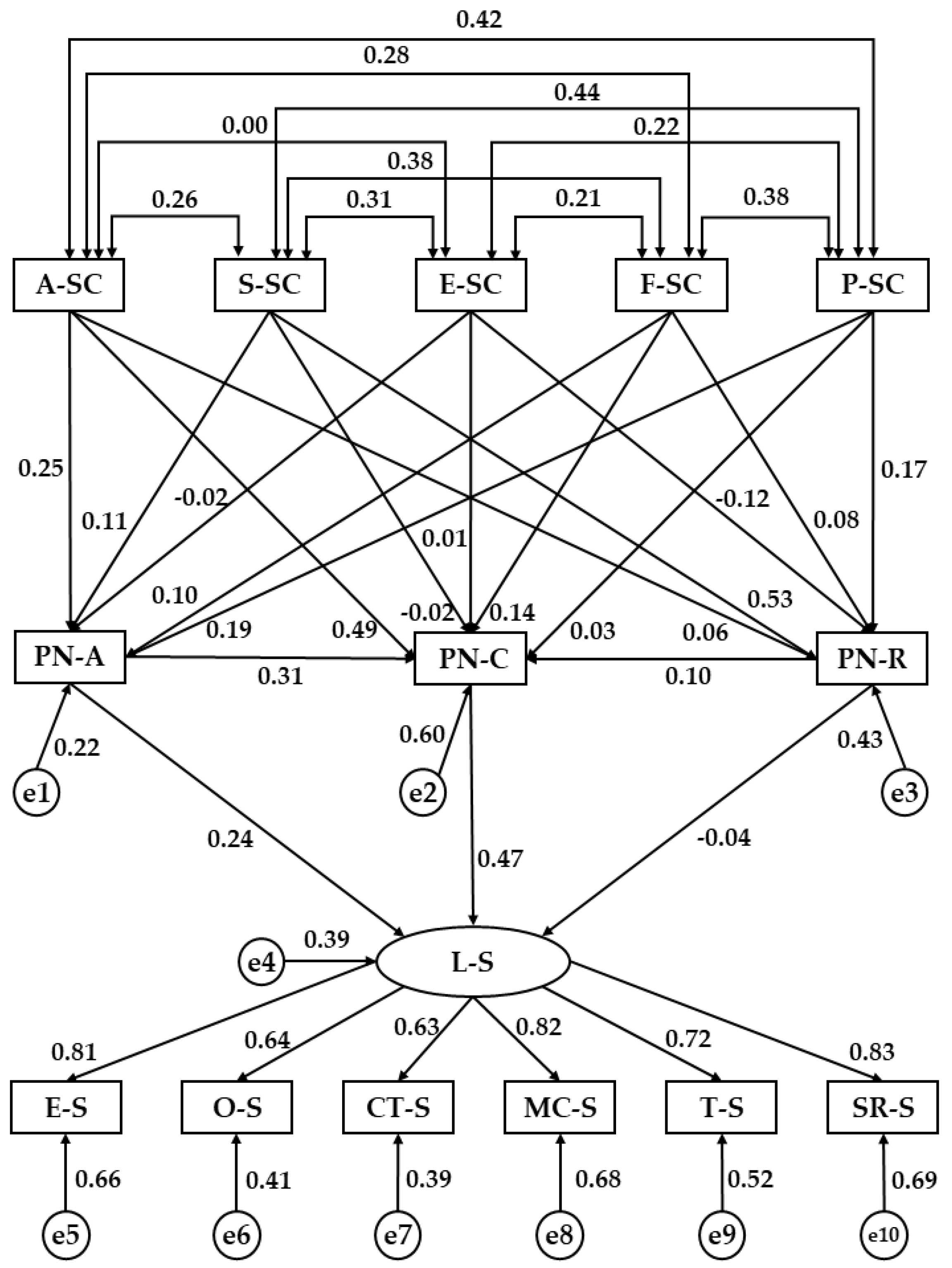

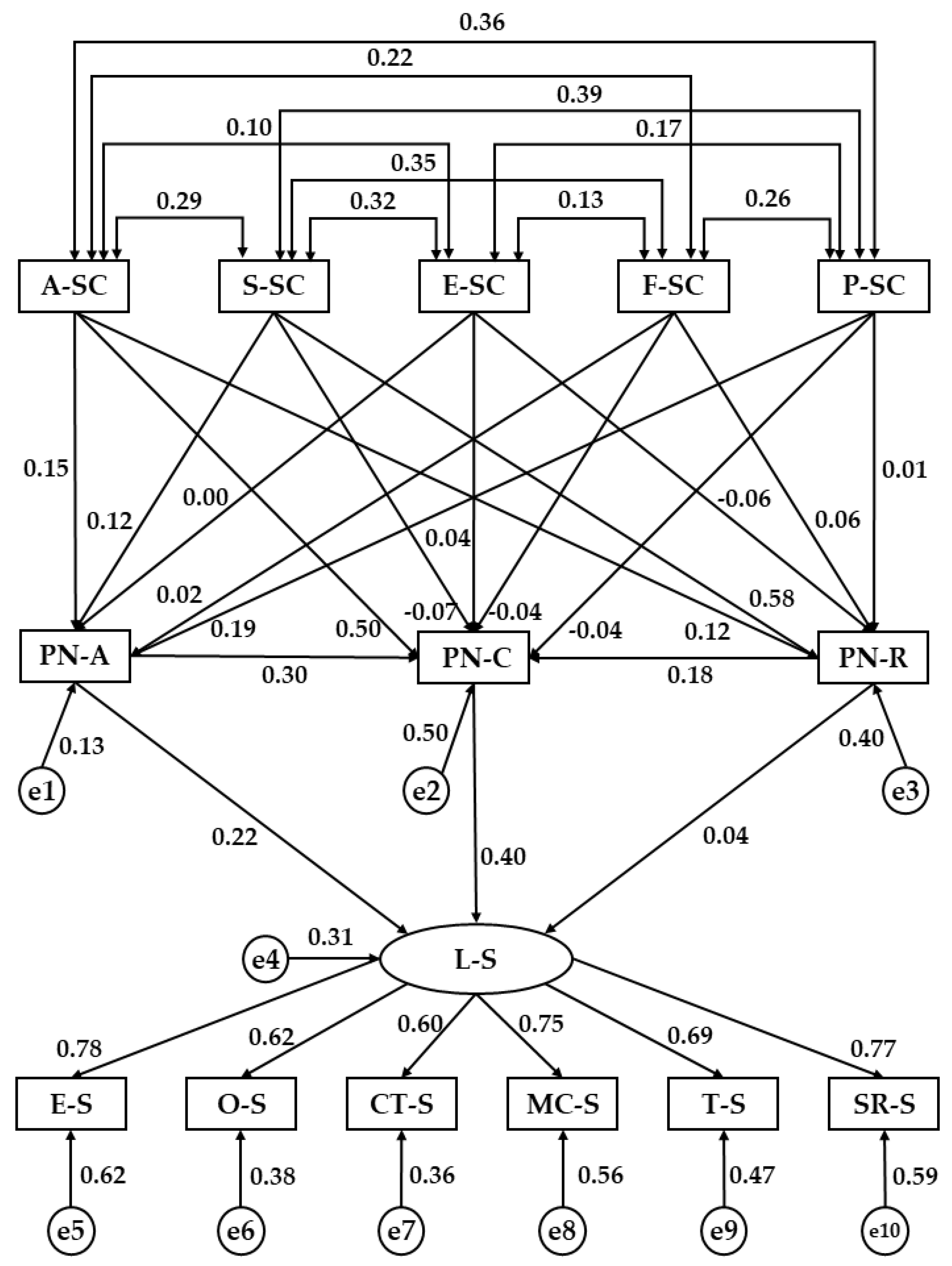

3. Results

4. Discussion

Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, N., Little, T. D., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory. In Development of self-determination through the life-course (pp. 47–54). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Akbag, M., & Ümmet, D. (2017). Predictive role of grit and basic psychological needs satisfaction on subjective well-being for young adults. Journal of Education and Practice, 8(26), 127–135. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, K., & Alanazi, S. (2021). The influences of conceptions of mathematics and self-directed learning skills on university students’ achievement in mathematics. European Journal of Education, 56(1), 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadó Codony, A., Alsina Tarrés, M., Senar Morera, F., Llop Escorihuela, E., Verdaguer Planas, M., Comas Matas, J., Gutiérrez del Moral, M. J., Ballester-Ferrando, D., Rodríguez-Roda Layret, I., Rostan Sánchez, C., Terradellas Piferrer, M. R., & Benito Mundet, H. (2025). Análisis combinado del clima académico y el ABP: Influencia en el engagement universitario. RELIEVE—Revista Electrónica De Investigación Y Evaluación Educativa, 31(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Animasaun, I. L., & Abegunrin, O. A. (2017). Gender difference, self-efficacy, active learning strategies and academic achievement of undergraduate students in the Department of Mathematical Sciences, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria. International Journal of Teaching and Case Studies, 8(4), 255–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, A. K., & Morin, A. J. (2016). Examination of the structure and grade-related differentiation of multidimensional self-concept instruments for children using ESEM. The Journal of Experimental Education, 84(2), 330–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J. (2014). The winding road from the late teens through the twenties: Emerging adulthood. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Augestad, L. B. (2017). Self-concept and self-esteem among children and young adults with visual impairment: A systematic review. Cogent Psychology, 4(1), 1319652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Arregui, E., & Arreguit, X. (2019). El futuro de la universidad y la universidad del futuro. Ecosistemas de formación continua para una sociedad de aprendizaje y enseñanza sostenible y responsable. Aula Abierta, 48(4), 447–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J. E., Kotrlik, J. W., & Higgins, C. C. (2001). Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size in survey research appropriate sample size in survey research. Information Technology, Learning, and Performance Journal, 19(1), 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, C., Rocchi, M., & Forneris, T. (2019). Using the learning climate questionnaire to assess basic psychological needs support in youth sport. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 32(2), 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88(3), 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berengüí-Gil, R., Castejón, M. A., Parra-Plaza, F. J., & López-Gullón, J. M. (2024). Burnout y rendimiento psicológico: Relaciones en jóvenes deportistas. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 16(2), 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. T., Jensen, M., & Hussong, A. M. (2023). Parent-emerging adult text interactions and emerging adult perceived parental support of autonomy. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 41(2), 499–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen, & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bülow, A., Keijsers, L., Boele, S., van Roekel, E., & Denissen, J. J. (2021). Parenting adolescents in times of a pandemic: Changes in relationship quality, autonomy support, and parental control? Developmental Psychology, 57(10), 1582–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Sánchez, M., Zurita-Ortega, F., García-Mármol, E., & Chacón-Cuberos, R. (2019). Motivational climate towards the practice of physical activity, self-concept, and healthy factors in the school environment. Sustainability, 11(4), 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón-Cuberos, R., Olmedo-Moreno, E. M., Lara-Sánchez, A. J., Zurita-Ortega, F., & Castro-Sánchez, M. (2019). Basic psychological needs, emotional regulation and academic stress in university students: A structural model according to branch of knowledge. Studies in Higher Education, 46(7), 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacón-Cuberos, R., Ramírez-Granizo, I., Ubago-Jiménez, J.L., & Castro-Sánchez, M. (2020). Multidimensional self-concept according to social and academic factors in university students. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 12(Suppl. 2), 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chacón-Cuberos, R., Zurita-Ortega, F., Castro-Sánchez, M., Espejo-Garcés, T., Martínez-Martínez, A., & Ruiz-Rico, G. (2018). The association of self-concept with substance abuse and problematic use of video games in university students: A structural equation model. Adicciones, 30(3), 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, E. C., Yu, T., & Hirsch, J. K. (2023). Perfectionism and academic stress in college students: Exploring the mediating role of emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 205, 112100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. T., Liou, S., & Chen, L. F. (2019). The relationships among gender, cognitive styles, learning strategies, and learning performance in the flipped classroom. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction, 35(4–5), 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drysdale, M. T., & McBeath, M. (2018). Motivation, self-efficacy and learning strategies of university students participating in work-integrated learning. Journal of Education and Work, 31(5–6), 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, A. A., Heath, N. L., & Mills, D. J. (2016). Basic psychological need satisfaction, emotion dysregulation, and non-suicidal self-injury engagement in young adults: An application of self-determination theory. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(3), 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergen, B., & Kanadli, S. (2017). The Effect of Self-Regulated Learning Strategies on Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis Study. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 69, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeili, L., Sohrabi, N., Mehryar, A. H., & Khayyer, M. (2019). A causal model of motivational beliefs with the mediating role of academic hope on academic self-efficacy in high school students. Iranian Evolutionary and Educational Psychology Journal, 1(3), 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fernández-Castillo, A., & Chacón-Borrego, F. (2022). The mediating role of academic self-concept between feedback and engagement in university students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(3), 459–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foerst, N. M., Klug, J., Jöstl, G., Spiel, C., & Schober, B. (2017). Knowledge vs. action: Discrepancies in university students’ knowledge about and self-reported use of self-regulated learning strategies. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F., Martínez, I., Balluerka, N., Cruise, E., Garcia, O. F., & Serra, E. (2018). Validation of the five-factor self-concept questionnaire AF5 in Brazil: Testing factor structure and measurement invariance across language (Brazilian and Spanish), gender, and age. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, F., & Musitu, G. (2001). Manual AF5 autoconcepto. TEA Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2010). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference (10th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Goroshit, M., & Hen, M. (2022). Feedback, academic self-concept, and emotional engagement: Their role in learning outcomes among university students. Teaching in Higher Education, 27(6), 751–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granados Alós, L., & Catalán-Gregori, B. (2025). Aplicación de la metodología aprendizaje-servicio en el ámbito universitario. European Public & Social Innovation Review, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadwin, A. F., Järvelä, S., & Miller, M. (2023). Self-regulated, co-regulated, and socially shared regulation of learning in online higher education: Current research and future directions. Internet and Higher Education, 56, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Haktanir, A., Watson, J. C., Ermis-Demirtas, H., Karaman, M. A., Freeman, P. D., Kumaran, A., & Streeter, A. (2021). Resilience, academic self-concept, and college adjustment among first-year students. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 23(1), 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattie, J. (2014). Self-concept. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henri, D. C., Morrell, L. J., & Scott, G. W. (2018). Student perceptions of their autonomy at university. Higher Education, 75(3), 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Y. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 38(1), 52–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M. S., & Jin, J. (2019). Exploring the basic psychological needs necessary for the internalized motivation of university students with smartphone overdependence: Applying a self-determination theory. Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 28(1), 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, K. M., & Kearns, D. M. (2022). Impostor phenomenon and academic identity: Challenges faced by underrepresented students in higher education. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 15(1), 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.-G., Sok, S., & Heng, K. (2024). The benefits of peer mentoring in higher education: Findings from a systematic review. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, (31). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobos, K., Cobo-Rendón, R., Bruna-Jofré, D., & Santana, J. (2024). New challenges for higher education: Self-regulated learning in blended learning contexts. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1457367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohbeck, A., Von Keitz, P., Hohmann, A., & Daseking, M. (2021). Children’s physical self-concept, motivation, and physical performance: Does physical self-concept or motivation play a mediating role? Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 669936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cassà, E., & Bisquerra-Alzina, R. (2024). Educar en las emociones en tiempos de crisis. RELIEVE—Revista Electrónica De Investigación Y Evaluación Educativa, 30(1), M1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M., & Nur, S. (2018). Exploring students’ learning strategies and gender differences in English language teaching. International Journal of Language Education, 2(1), 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Clares, P., & González-Lorente, C. (2019). Personal and interpersonal competencies of university students entering the workforce: Validation of a scale. RELIEVE, 25(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, L., Sampaio, D., Ferreira, T., & Gonçalves, F. (2022). Autonomy-supportive teaching and academic engagement: The mediating role of psychological needs satisfaction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 113, 103646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejeh, M., Stampfli, B., & Hascher, T. (2024). Understanding the promotion of self-regulated learning in upper secondary schools: How can teaching quality criteria contribute? Frontline Learning Research, 12(4), 55–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthuri, R. N., & Arasa, J. (2017). Gender differences in self-concept among a sample of students of the United States; international university in Africa. Annals of Behavioural Science, 3(2), 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrington, J. (2020). Adolescent peer victimization, self-concept, and psychological distress in emerging adulthood. Youth & Society, 53(2), 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onetti-Onetti, W., Chinchilla-Minguet, J. L., Martins, F. M. L., & Castillo-Rodriguez, A. (2019). Self-concept and physical activity: Differences between high-school and university students in Spain and Portugal. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paloș, R., Vîrgă, D., & Okros, N. (2024). Why should you believe in yourself? Students’ performance-approach goals shape their approach to learning through self-efficacy: A longitudinal analysis. European Journal of Education, 59, e12624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, E., & Alonso-Tapia, J. (2013). Self-assessment: Theoretical and practical connotations. When it happens, how is it acquired and what to do to develop it in our students. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 11(2), 551–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, A., Han, F., & Ellis, R. A. (2016). Combining university student self-regulated learning indicators and engagement with online learning events to predict academic performance. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 10(1), 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, P. D., Trautwein, U., Marsh, H. W., Basarkod, G., & Dicke, T. (2020). Development in relationship self-concept from high school to university predicts adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 56(8), 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A., Garcia, T., & McKeachie, W. J. (1993). Reliability and predictive validity of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ). Educational and Psychological Measurement, 53(3), 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadlin, N. (2018). The mark of a woman’s record: Gender and academic performance in hiring. American Sociological Review, 83(2), 331–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J., & Cheon, S. H. (2021). Autonomy-supportive teaching in higher education: Motivating students through instructional support. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(4), 711–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reggiani, C. F. (2013). Necesidades psicológicas básicas, enfoques de aprendizaje y atribución de la motivación al logro en estudiantes universitarios. Estudio exploratorio. Revista de Estilos de Aprendizaje, 6(11), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Respondek, L., Seufert, T., Hamm, J. M., & Nett, U. E. (2020). Linking changes in perceived academic control to university dropout and university grades: A longitudinal approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(5), 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezai, M., Vahhab, Z., Izadi, F., & Jahanbani, F. (2025). Examining the Mediating Role of Digital Self-Efficacy in the Relationship Between Academic Self-Concept and Academic Performance of Students. Journal of Adolescent and Youth Psychological Studies, 5(11), 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, L., Saucedo, C., Caliusco, M., & Gutiérrez, M. (2019). Supporting self-regulated learning and personalization using ePortfolios: A semantic approach based on learning paths. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior (2nd ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sabogal, L. F., Barraza, E., Hern, A., & Zapata, L. (2011). Validación del cuestionario de motivación y estrategias de aprendizaje forma corta–MSLQ SF, en estudiantes universitarios de una institución pública-Santa Marta. Psicogente, 14(25), 36–50. [Google Scholar]

- Shavelson, J., Hubner, J. J., & Stanton, G. C. (1976). Self-concept: Validation of construct interpretations. Review of Educational Research, 46(3), 407–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K. M., & Hilpert, J. C. (2012). The balanced measure of psychological needs (BMPN) scale: An alternative domain general measure of need satisfaction. Motivation and Emotion, 36(4), 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J. Y., Steger, M. F., & Henry, K. L. (2016). Self-concept clarity’s role in meaning in life among American college students: A latent growth approach. Self and Identity, 15(2), 206–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoet, G., & Geary, D. C. (2015). Sex differences in academic achievement are not related to political, economic, or social equality. Intelligence, 48, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhlmann, M., Sassenberg, K., Nagengast, B., & Trautwein, U. (2018). Belonging mediates effects of student-university fit on well-being, motivation, and dropout intention. Social Psychology, 49, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theobald, M. (2021). Self-regulated learning training programs enhance university students’ academic performance, self-regulated learning strategies, and motivation: A meta-analysis. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 66, 101976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, A. C., & Rubie-Davies, C. M. (2022). Gender and minority background as moderators of teacher expectation effects on self-concept, subjective task values, and academic performance. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 38(4), 1677–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Sahão, F., & Kienen, N. (2021). Adaptação e saúde mental do estudante universitário: Revisão Sistemática da literatura. Psicologia Escolar e Educacional, 25, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Zanden, P. J. A. C., Denessen, E., Cillessen, A. H. N., & Meijer, P. C. (2018). Domains and predictors of first-year student success: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 23, 57–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuzalp, N., & Bahcivan, E. (2021). A structural equation modeling analysis of relationships among university students’ readiness for e-learning, self-regulation skills, satisfaction, and academic achievement. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 16(1), 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Association Between Variables | RW | SRW | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EST | ES | CR | p | EST | |||

| PN-A | ← | A-SC | 0.256 | 0.034 | 7.499 | *** | 0.246 |

| PN-A | ← | S-SC | 0.102 | 0.033 | 3.061 | ** | 0.105 |

| PN-A | ← | E-SC | −0.014 | 0.028 | −0.506 | 0.613 | −0.016 |

| PN-R | ← | E-SC | −0.121 | 0.026 | −4.620 | *** | −0.124 |

| PN-R | ← | F-SC | 0.094 | 0.033 | 2.875 | ** | 0.081 |

| PN-R | ← | P-SC | 0.170 | 0.031 | 5.507 | *** | 0.168 |

| PN-R | ← | A-SC | 0.069 | 0.032 | 2.167 | * | 0.061 |

| PN-R | ← | S-SC | 0.553 | 0.031 | 17.893 | *** | 0.528 |

| PN-A | ← | F-SC | 0.106 | 0.035 | 2.994 | ** | 0.099 |

| PN-A | ← | P-SC | 0.177 | 0.033 | 5.283 | *** | 0.188 |

| PN-C | ← | E-SC | 0.004 | 0.018 | 0.228 | 0.820 | 0.005 |

| PN-C | ← | A-SC | 0.452 | 0.022 | 20.298 | *** | 0.489 |

| PN-C | ← | S-SC | −0.018 | 0.025 | −0.716 | 0.474 | −0.020 |

| PN-C | ← | F-SC | 0.131 | 0.023 | 5.835 | *** | 0.138 |

| PN-C | ← | P-SC | 0.023 | 0.022 | 1.051 | 0.293 | 0.027 |

| PN-C | ← | PN-A | 0.277 | 0.021 | 13.347 | *** | 0.313 |

| PN-C | ← | PN-R | 0.079 | 0.022 | 3.529 | *** | 0.097 |

| L-S | ← | PN-A | 0.178 | 0.026 | 6.830 | *** | 0.235 |

| L-S | ← | PN-C | 0.404 | 0.031 | 12.842 | *** | 0.473 |

| L-S | ← | PN-R | −0.031 | 0.021 | −1.464 | 0.143 | −0.044 |

| SR-S | ← | L-S | 1.000 | - | - | *** | 0.828 |

| T-S | ← | L-S | 0.924 | 0.038 | 24.104 | *** | 0.724 |

| MC-S | ← | L-S | 0.925 | 0.032 | 28.656 | *** | 0.822 |

| CT-S | ← | L-S | 0.806 | 0.040 | 20.070 | *** | 0.626 |

| O-S | ← | L-S | 0.974 | 0.047 | 20.624 | *** | 0.640 |

| E-S | ← | L-S | 0.930 | 0.033 | 28.206 | *** | 0.813 |

| P-SC | ↔ | A-SC | 0.204 | 0.017 | 11.728 | *** | 0.418 |

| A-SC | ↔ | S-SC | 0.122 | 0.016 | 7.580 | *** | 0.258 |

| A-SC | ↔ | E-SC | −0.001 | 0.017 | −0.057 | 0.954 | −0.002 |

| A-SC | ↔ | F-SC | 0.118 | 0.015 | 8.088 | *** | 0.276 |

| S-SC | ↔ | E-SC | 0.170 | 0.019 | 9.058 | *** | 0.312 |

| S-SC | ↔ | F-SC | 0.172 | 0.016 | 10.682 | *** | 0.376 |

| P-SC | ↔ | S-SC | 0.230 | 0.019 | 12.180 | *** | 0.438 |

| E-SC | ↔ | F-SC | 0.101 | 0.017 | 6.116 | *** | 0.205 |

| P-SC | ↔ | E-SC | 0.124 | 0.019 | 6.571 | *** | 0.221 |

| P-SC | ↔ | F-SC | 0.181 | 0.017 | 10.826 | *** | 0.381 |

| Associations Between Variables | RW | SRW | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EST | ES | CR | p | EST | |||

| PN-A | ← | A-SC | 0.166 | 0.027 | 6.076 | *** | 0.146 |

| PN-A | ← | S-SC | 0.110 | 0.023 | 4.768 | *** | 0.124 |

| PN-A | ← | E-SC | 0.003 | 0.019 | 0.142 | 0.887 | 0.003 |

| PN-R | ← | E-SC | −0.052 | 0.018 | −2.874 | ** | −0.055 |

| PN-R | ← | F-SC | 0.062 | 0.021 | 2.939 | ** | 0.058 |

| PN-R | ← | P-SC | 0.011 | 0.021 | 0.520 | 0.603 | 0.011 |

| PN-R | ← | A-SC | 0.152 | 0.026 | 5.921 | *** | 0.118 |

| PN-R | ← | S-SC | 0.579 | 0.022 | 26.806 | *** | 0.577 |

| PN-A | ← | F-SC | 0.018 | 0.023 | 0.785 | 0.432 | 0.019 |

| PN-A | ← | P-SC | 0.171 | 0.022 | 7.656 | *** | 0.192 |

| PN-C | ← | E-SC | 0.024 | 0.012 | 2.001 | * | 0.035 |

| PN-C | ← | A-SC | 0.467 | 0.018 | 26.657 | *** | 0.497 |

| PN-C | ← | S-SC | −0.048 | 0.017 | −2.776 | ** | −0.065 |

| PN-C | ← | F-SC | 0.060 | 0.014 | 4.215 | *** | 0.077 |

| PN-C | ← | P-SC | −0.031 | 0.014 | −2.213 | * | −0.043 |

| PN-C | ← | PN-A | 0.245 | 0.015 | 16.566 | *** | 0.296 |

| PN-C | ← | PN-R | 0.135 | 0.016 | 8.547 | *** | 0.185 |

| L-S | ← | PN-A | 0.134 | 0.015 | 9.096 | *** | 0.223 |

| L-S | ← | PN-C | 0.293 | 0.019 | 15.072 | *** | 0.401 |

| L-S | ← | PN-R | 0.024 | 0.012 | 1.921 | 0.055 | 0.045 |

| SR-S | ← | L-S | 1.000 | - | - | *** | 0.769 |

| T-S | ← | L-S | 1.009 | 0.035 | 28.743 | *** | 0.689 |

| MC-S | ← | L-S | 1.038 | 0.033 | 31.361 | *** | 0.747 |

| CT-S | ← | L-S | 0.948 | 0.038 | 24.848 | *** | 0.602 |

| O-S | ← | L-S | 1.032 | 0.040 | 25.646 | *** | 0.620 |

| E-S | ← | L-S | 1.067 | 0.032 | 33.022 | *** | 0.784 |

| P-SC | ↔ | A-SC | 0.167 | 0.011 | 14.559 | *** | 0.364 |

| A-SC | ↔ | S-SC | 0.135 | 0.011 | 11.955 | *** | 0.293 |

| A-SC | ↔ | E-SC | 0.048 | 0.012 | 4.146 | *** | 0.098 |

| A-SC | ↔ | F-SC | 0.093 | 0.010 | 9.011 | *** | 0.217 |

| S-SC | ↔ | E-SC | 0.205 | 0.016 | 13.095 | *** | 0.323 |

| S-SC | ↔ | F-SC | 0.193 | 0.014 | 14.113 | *** | 0.352 |

| P-SC | ↔ | S-SC | 0.229 | 0.015 | 15.444 | *** | 0.389 |

| E-SC | ↔ | F-SC | 0.079 | 0.014 | 5.680 | *** | 0.135 |

| P-SC | ↔ | E-SC | 0.109 | 0.015 | 7.265 | *** | 0.173 |

| P-SC | ↔ | F-SC | 0.144 | 0.013 | 10.829 | *** | 0.263 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chacón-Cuberos, R.; Serrano-García, J.; Serrano-García, I.; Castro-Sánchez, M. Self-Concept Modulates Motivation and Learning Strategies in Higher Education: Comparison According to Sex. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070873

Chacón-Cuberos R, Serrano-García J, Serrano-García I, Castro-Sánchez M. Self-Concept Modulates Motivation and Learning Strategies in Higher Education: Comparison According to Sex. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):873. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070873

Chicago/Turabian StyleChacón-Cuberos, Ramón, Jennifer Serrano-García, Inmaculada Serrano-García, and Manuel Castro-Sánchez. 2025. "Self-Concept Modulates Motivation and Learning Strategies in Higher Education: Comparison According to Sex" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070873

APA StyleChacón-Cuberos, R., Serrano-García, J., Serrano-García, I., & Castro-Sánchez, M. (2025). Self-Concept Modulates Motivation and Learning Strategies in Higher Education: Comparison According to Sex. Education Sciences, 15(7), 873. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070873