Students’ Motivation for Classroom Music: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What are the common methodological approaches and data collection tools used in studies examining motivation in music classrooms?

- RQ2: How do motivational constructs vary across different demographic factors such as gender, age, and type of learner (music learners or non-music learners)?

- RQ3: What are the key differences in motivational levels between music and other academic subjects?

- RQ4: What strategies have been suggested in the literature to improve student motivation in music classrooms, and how effective are these strategies?

2. Method

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

music AND (education OR class* OR lesson) AND (motivation OR attitude)

2.3. Selection and Extraction Procedures

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment and Effect Measures

2.5. Synthesis Methods

3. Results

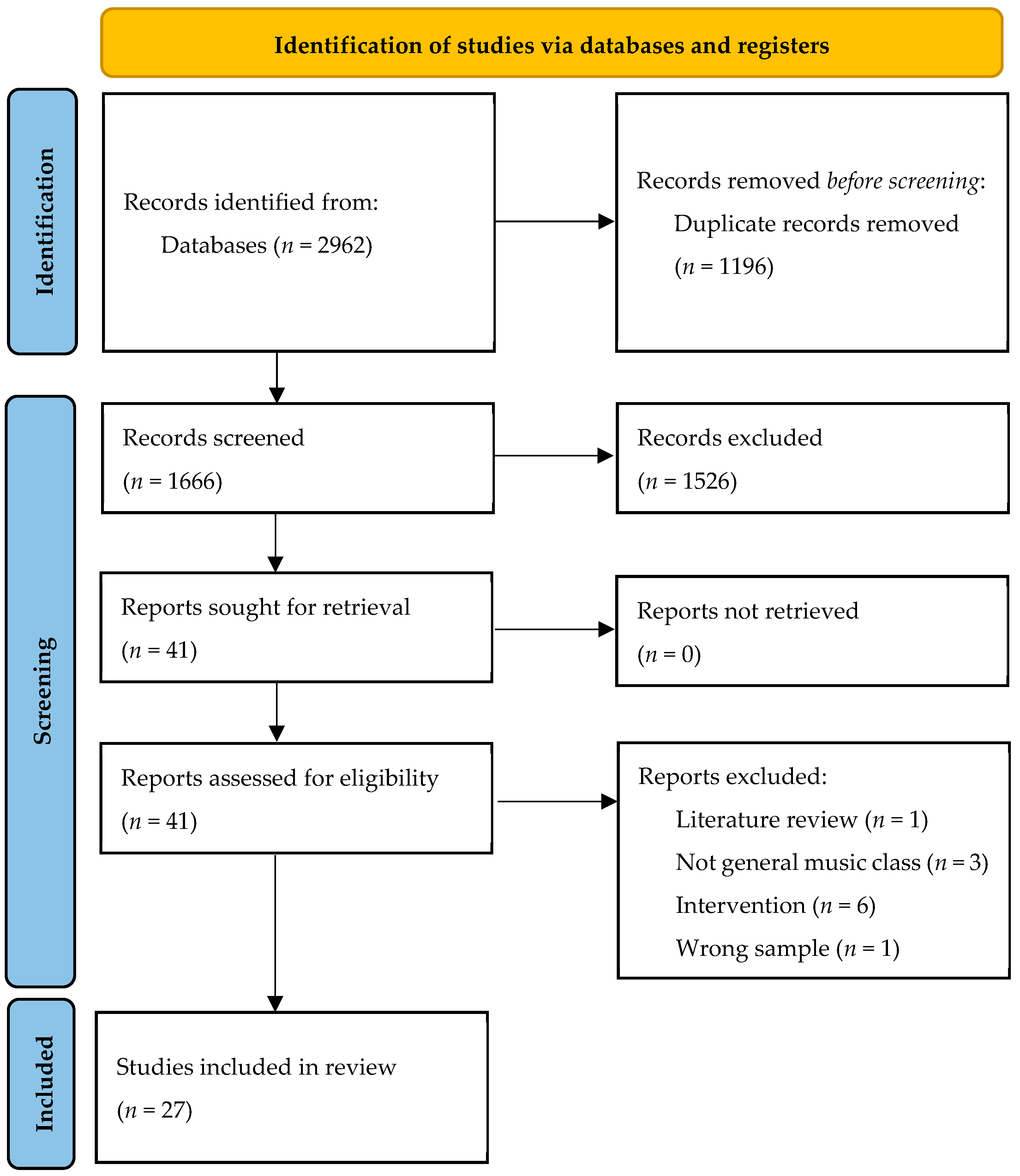

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Methodological Results

3.3.1. Samplings of the Reviewed Studies

3.3.2. Methodological Design of the Reviewed Studies

3.3.3. Data Collection Tools of the Reviewed Studies

3.4. Theoretical Frameworks or Motivational Constructs

3.5. Key Findings Related to Student Motivation

3.5.1. Motivational Differences Based on Gender

3.5.2. Motivational Differences Based on Age

3.5.3. Motivational Differences Between Music Learners and Non-Music Learners

3.5.4. Motivational Differences Between Music and Other Subjects

3.5.5. Activities of the Music Lesson

3.5.6. Strategies for Improving Motivation

4. Discussion

4.1. General Interpretation of the Results

4.2. Limitations of the Included Evidence

4.3. Limitations of the Review Process

4.4. Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author and Year | Country | Age/Grade | Sample Size | Design | Data Collection Tools | Motivational Construct |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (González-Moreno, 2010) | Mexico | NA/4–12th | 3613 | International mapping exercise | Questionnaire developed for the international mapping exercise. | Expectancy–value theory |

| (Hentschke, 2010) | Brazil | NA/6–12th | 1848 | International mapping exercise | Questionnaire developed for the international mapping exercise. | Expectancy–value theory |

| (Leung & McPherson, 2010) | Hong Kong | 14–17/9–11th | 4495 | International mapping exercise | Questionnaire developed for the international mapping exercise. | Expectancy–value theory |

| (McPherson & Hendricks, 2010) | USA | NA/6–12th | 3037 | International mapping exercise | Questionnaire developed for the international mapping exercise. | Expectancy–value theory |

| (McPherson & O’Neill, 2010) | 8-country | NA/4–12th | 24,143 | International mapping exercise | Questionnaire developed for the international mapping exercise. | Expectancy–value theory |

| (Portowitz et al., 2010) | Israel | NA/5–12th | 2257 | International mapping exercise | Questionnaire developed for the international mapping exercise. | Expectancy–value theory |

| (Juvonen, 2011) | Finland | NA/5–12th | 1654 | International mapping exercise | Questionnaire developed for the international mapping exercise. | Expectancy–value theory |

| (Lowe, 2011) | Australia | 12–13/8th | 222 | Test and re-test | 5-point Likert scale on attainment, intrinsic values, and utility values developed by the researcher. | Expectancy–value theory |

| (Seog et al., 2011) | South Korea | NA/5–12th | 2671 | International mapping exercise | Questionnaire developed for the international mapping exercise. | Expectancy–value theory |

| (Xie & Leung, 2011) | China | NA/5–12th | 2750 | International mapping exercise | Questionnaire developed for the international mapping exercise. | Expectancy–value theory |

| (Arriaga Sanz & Madariaga Orbea, 2014) | Spain | 11–13/6th | 116 | Survey | Motivation test; | NA |

| Questionnaire of Academic Goals; | ||||||

| Sidney Attribution Scale; | ||||||

| items on the perception of difficulty, habits and preferences, and family habits. | ||||||

| (McPherson et al., 2015) | Australia | 5–12/NA | 2727 | Survey | Adaptation of the questionnaire developed for the international mapping exercise. | Expectancy–value theory |

| (Kokotsaki, 2017) | England | NA/6–7th | 352 | Qualitative method | Researcher-designed semi-structured focus-group interviews; | NA |

| Adaptation of Attitudes to Music questionnaire. | ||||||

| (Freer & Evans, 2018) | Australia | NA/7–8th | 204 | Survey | Balanced Measure of Psychological Needs; | Expectancy–value theory, self-determination theory |

| Motivation and Engagement Scale—High School; | ||||||

| items on instrumental experience and elective intentions. | ||||||

| (Freer & Evans, 2019) | Australia | NA/7–8th | 395 | Survey | Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction and Frustration Scale; | Self-determination theory |

| items on elective intentions based on the theory of planned behavior; | ||||||

| 7-point Likert scale on perceived teacher needs support (autonomy, competence, relatedness); | ||||||

| teachers providing students’ grades; | ||||||

| SES based on the Australian Socioeconomic Index; | ||||||

| report on prior music learning. | ||||||

| (McCarthy et al., 2019) | Ireland | 16–17/NA | 24 | Qualitative method | Semi-structured interviews were designed by the researcher. | NA |

| (Mawang et al., 2020) | Kenya | 16–21/12th | 201 | Survey | Adaptation of Achievement Goal Questionnaire-Revised; | Achievement goal theory |

| Adaptation of Motivated Strategies for Learning Questionnaire; | ||||||

| Adaptation of Consensual Assessment Technique. | ||||||

| (Kingsford-Smith & Evans, 2021) | Australia | NA/7–8th | 180 | Two-wave longitudinal study | Adaptation of Balanced Measure of Psychological Needs; | Self-determination theory |

| Motivation and Engagement Scale; | ||||||

| report on expected grade; | ||||||

| 7-point Likert scale on elective intentions. | ||||||

| (Mustafa, 2021) | Turkey | 9–14/NA | 64 | Survey | Items about students’ demographic features; | NA |

| Music Education Lessons Attitude Scale. | ||||||

| (Stavrou & Papageorgi, 2021) | Cyprus | 12–14/sec.sch. A–C | 749 | Mixed-method research design | Self-report questionnaire designed by the researcher. | NA |

| (Kibici, 2022) | Turkey | NA/5–8th | 246 | Causal comparative research | Kaufman Creativity Scale; | NA |

| music achievement scale based on the Music Lesson Curriculum; | ||||||

| Attitude Towards Music Scale. | ||||||

| (Venter & Panebianco, 2022) | South Africa | 15–16/9–10th | 180 | Survey | Adaptation of the questionnaire developed for the international mapping exercise; | Expectancy–value theory |

| items on elective intentions. | ||||||

| (Janurik et al., 2023) | Hungary | NA/7th | 139 | Survey | Musical Mastery Motivation Questionnaire; | Mastery motivation |

| Adjusted Musical SC Inquiry; | ||||||

| items on elective instrumental training, usefulness of school music, musical family background, mother’s level of education, and music grade. | ||||||

| (Kokotsaki & Whitford, 2023) | England | NA/7–9th | 37 | Qualitatively driven mixed methods | Interview questions designed by the researcher. | NA |

| (Papageorgi & Economidou Stavrou, 2023) | Cyprus | 12–14/sec.sch. 1st–3rd | 749 | Survey | Ad hoc self-report questionnaire; | NA |

| Classroom Environment Scale adapted to Greek students. | ||||||

| (Whitford & Kokotsaki, 2024) | England | 11–14/7–9th | 581 | Mixed-method research design | Researcher-designed questionnaire on students’ enjoyment, attitude, the importance attributed to music compared to other subjects, elective intentions, and out-of-school musical activities. | NA |

References

- Arriaga Sanz, C., & Madariaga Orbea, J. M. (2014). Is the perception of music related to musical motivation in school? Music Education Research, 16(4), 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmus, E. P. (2021). Motivation in music teaching and learning. Visions of Research in Music Education, 16(5), 31. Available online: https://digitalcommons.lib.uconn.edu/vrme/vol16/iss5/31/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Burak, S. (2014). Motivation for instrument education: A study from the perspective of expectancy-value and flow theories. Egitim Arastirmalari—Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 55, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chraif, M., Mitrofan, L., Golu, F., & Gâtej, E. (2014). The influence of progressive rock music on motivation regarding personal goals, motivation regarding competition and level of aspiration on young students in psychology. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 127(2007), 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comeau, G., Huta, V., Lu, Y., & Swirp, M. (2019). The Motivation for Learning Music (MLM) questionnaire: Assessing children’s and adolescents’ autonomous motivation for learning a musical instrument. Motivation and Emotion, 43(5), 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P. (2023). Motivation and self-regulation in music, musicians, and music education. In R. M. Ryan, & E. L. Deci (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of self-determination theory. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P., & Bonneville-Roussy, A. (2016). Self-determined motivation for practice in university music students. Psychology of Music, 44(5), 1095–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P., & Liu, M. Y. (2019). Psychological needs and motivational outcomes in a high school orchestra program. Journal of Research in Music Education, 67(1), 83–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freer, E., & Evans, P. (2018). Psychological needs satisfaction and value in students’ intentions to study music in high school. Psychology of Music, 46(6), 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freer, E., & Evans, P. (2019). Choosing to study music in high school: Teacher support, psychological needs satisfaction, and elective music intentions. Psychology of Music, 47(6), 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moreno, P. A. (2010). Students’ motivation to study music: The Mexican context. Research Studies in Music Education, 32(2), 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentschke, L. (2010). Students’ motivation to study music: The Brazilian context. Research Studies in Music Education, 32(2), 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janurik, M., Oo, T. Z., Kis, N., Szabó, N., & Józsa, K. (2023). The dynamics of mastery motivation and its relationship with self-concept in music education. Behavioral Sciences, 13(8), 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juvonen, A. (2011). Students’ motivation to study music: The Finnish context. Research Studies in Music Education, 33(1), 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibici, V. B. (2022). An analysis of the relationships between secondary school students’ creativity, music achievement and attitudes. International Journal on Social and Education Sciences, 4(1), 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsford-Smith, A., & Evans, P. (2021). A longitudinal study of psychological needs satisfaction, value, achievement, and elective music intentions. Psychology of Music, 49(3), 382–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotsaki, D. (2016). Pupils’ attitudes to school and music at the start of secondary school. Educational Studies, 42(2), 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotsaki, D. (2017). Pupil voice and attitudes to music during the transition to secondary school. British Journal of Music Education, 34(1), 5–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotsaki, D., & Hallam, S. (2011). The perceived benefits of participative music making for non-music university students: A comparison with music students. Music Education Research, 13(2), 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokotsaki, D., & Whitford, H. (2023). Students’ attitudes to school music and perceived barriers to GCSE music uptake: A phenomenographic approach. British Journal of Music Education, 41(1), 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, B. W., & McPherson, G. E. (2010). Students’ motivation in studying music: The Hong Kong context. Research Studies in Music Education, 32(2), 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, G. (2011). Class music learning activities: Do students find them important, interesting and useful? Research Studies in Music Education, 33(2), 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawang, L. L., Kigen, E. M., & Mutweleli, S. M. (2020). Achievement goal motivation and cognitive strategies as predictors of musical creativity among secondary school music students. Psychology of Music, 48(3), 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C., O’Flaherty, J., & Downey, J. (2019). Choosing to study music: Student attitudes towards the subject of music in second-level education in the Republic of Ireland. British Journal of Music Education, 36(2), 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, G. E., & Hendricks, K. S. (2010). Students’ motivation to study music: The United States of America. Research Studies in Music Education, 32(2), 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, G. E., & O’Neill, S. A. (2010). Students’ motivation to study music as compared to other school subjects: A comparison of eight countries. Research Studies in Music Education, 32(2), 101–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPherson, G. E., Osborne, M. S., Barrett, M. S., Davidson, J. W., & Faulkner, R. (2015). Motivation to study music in Australian schools: The impact of music learning, gender, and socio-economic status. Research Studies in Music Education, 37(2), 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, K. (2021). Examination of the music lesson behavior of students studying at primary education level. Educational Research and Reviews, 16(2), 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C. (2017). Australian primary students’ motivation and learning intentions for extra-curricular music programmes. Music Education Research, 19(3), 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgi, I., & Economidou Stavrou, N. (2023). Student perceptions of the classroom environment, student characteristics, and motivation for music lessons at secondary school. Musicae Scientiae, 27(2), 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portowitz, A., González-Moreno, P. A., & Hendricks, K. S. (2010). Students’ motivation to study music: Israel. Research Studies in Music Education, 32(2), 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seog, M., Hendricks, K. S., & González-Moreno, P. A. (2011). Students’ motivation to study music: The South Korean context. Research Studies in Music Education, 33(1), 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M. (2022). Self-Determination theory for motivation in distance music education. Journal of Music Teacher Education, 31(2), 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B. P. (2015). Motivation to learn music: A discussion of some key elements. In MENC Handbook of Research on Music Learning: Volume 1 Strategies. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Quadros Júnior, J. F., Lorenzo, O., Herrera, L., & Araújo Santos, N. S. (2019). Gender and religion as factors of individual differences in musical preference. Musicae Scientiae, 23(4), 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrou, N. E., & Papageorgi, I. (2021). ‘Turn up the volume and listen to my voice’: Students’ perceptions of Music in school. Research Studies in Music Education, 43(3), 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strenacikova, M., & Strenacikova, M. (2020). Achievement motivation and its impact on music students’ performance and practice in tertiary level education. Music Scholarship, 0854(2), 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, L., & Panebianco, C. (2022). High school learners’ perceptions of value as motivation to choose music as an elective in Gauteng, South Africa. International Journal of Music Education, 40(2), 244–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitford, H., & Kokotsaki, D. (2024). Enjoyment of music and GCSE uptake: Survey findings from three North East schools in England. British Journal of Music Education, 41(2), 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., & Leung, B. W. (2011). Students’ motivation to study music: The mainland China context. Research Studies in Music Education, 33(1), 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., & Xu, J. (2018). Homework expectancy value scale: Measurement invariance and latent mean differences across gender. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 36(8), 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Motivational Constructs | No. of Studies | Assessed Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Expectancy–value theory | 13 | Competence beliefs, perceived task difficulty, values (interest, importance, and usefulness) |

| Self-determination theory | 3 | Basic psychological needs: autonomy, competence, relatedness |

| Mastery motivation | 1 | Instrumental component: rhythm acquisition, singing acquisition, acquisition of music reading, musical knowledge. Expressive component: musical mastery pleasure, negative reaction to musical failure |

| Achievement goal theory | 1 | Mastery approach, performance approach, performance-avoidance goals |

| Country | No. of Studies | Trend by Age | Trend by Gender | Trend by Learner Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | 5 | decreases/stable | girls/no difference | music learners |

| Brazil | 1 | increases | - | - |

| China | 1 | decreases | - | - |

| Cyprus | 2 | decreases/stable | girls | music learners |

| England | 4 | decreases | girls | music learners |

| Finland | 1 | decreases | girls | music learners |

| Hong Kong | 1 | decreases | - | |

| Hungary | 1 | - | girls | no difference |

| Ireland | 1 | - | - | music learners |

| Israel | 1 | decreases | - | music learners |

| Kenya | 1 | - | - | - |

| Mexico | 1 | - | - | music learners |

| South Africa | 1 | increases | boys not sig. | - |

| South Korea | 1 | decreases | - | - |

| Spain | 1 | - | - | no difference |

| Turkey | 2 | decreases | girls/no difference | music learners |

| USA | 1 | decreases | music learners |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kiss, B.; Oo, T.Z.; Biró, F.; Józsa, K. Students’ Motivation for Classroom Music: A Systematic Literature Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070862

Kiss B, Oo TZ, Biró F, Józsa K. Students’ Motivation for Classroom Music: A Systematic Literature Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):862. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070862

Chicago/Turabian StyleKiss, Bernadett, Tun Zaw Oo, Fanni Biró, and Krisztián Józsa. 2025. "Students’ Motivation for Classroom Music: A Systematic Literature Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070862

APA StyleKiss, B., Oo, T. Z., Biró, F., & Józsa, K. (2025). Students’ Motivation for Classroom Music: A Systematic Literature Review. Education Sciences, 15(7), 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070862