Abstract

School has been identified as a suitable arena for targeting improvements in the health of children and young people. Teachers are highlighted as crucial contributors to student health which has resulted in changes in the teaching profession. The aim of this study is to examine the students’ perspective on the role of the teacher in working with student health. Interviews with 34 students aged 16–19 years were carried out. Data were analysed using qualitative content analysis with theoretical underpinnings from pragmatism and symbolic interactionism. This approach identified four dominating roles for teachers: (1) a creator of joyful learning, (2) a creator of a sense of control, (3) a spreader of happiness, and (4) a creator of feeling valued. This study shows that the role of the teacher in working with student health is in acting, not in being, and that this role is constantly (re)created through interaction. The student perspective on the role of the teacher in student health work has close similarities to the role of the teacher in inclusive teaching, merging relational competence with didactic skill. In conclusion, we argue that developing teachers’ didactic as well as relational competency, along with understanding competence within a pragmatic and symbolic interactionist theoretical framework, could improve student health practices.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, global and national reports have indicated that health has been declining among children and young people, especially mental health. In 2021, the World Health Organization (2021) reported that one in seven 10- to 19-year-olds experienced a mental disorder and noted that failing to address youth mental health issues could result in limited opportunities for young people to live fulfilling adult lives. School has been identified as a suitable arena for targeting improvements in the health of children and young people. Furthermore, in recent years growing expectations have been placed on teachers to engage with student health, both on a global scale (Gunawardena et al., 2024; Berg et al., 2024; Tamburrino et al., 2020) and in Sweden (SFS 2010:800; Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023), where the present study was conducted.

In a broad sense, the current study can be seen as part of the research field of teachers’ working conditions in relation to policy changes (Erlandson & Karlsson, 2018; Furlong et al., 2008; Stillman & Anderson, 2015). More specifically, however, this work can be viewed as a contribution to the study of teachers’ professional roles in contemporary education, especially in relation to student health care. Research regarding student health is mostly published in healthcare-related and not pedagogical journals (Ragnarsson et al., 2020) and thus perhaps does not reach pedagogical practice. We consider working with student health to be a pedagogical as well as a healthcare issue closely linked to the professional role of the teacher and pedagogical practice, calling for research from a pedagogical perspective.

In this study, we examine the teaching profession through a student perspective, which could be considered unorthodox. However, promoting health involves participation and empowerment (World Health Organization, 1998), and the voices of those whose health is being promoted need to be heard. To achieve participation and, in turn, good health, students need to be involved in research regarding their own health. The aim of this study thus is to examine the perspective of students on the teachers’ role in working with student health. The following research question is answered and discussed: What dominating roles in teachers’ work with student health care are (re)created in students’ descriptions?

2. Theoretical, Conceptual, and Contextual Framework

2.1. Theoretical Framework

This study has theoretical underpinnings from pragmatism and symbolic interactionism (Biesta & Burbules, 2003; Blumer, 1969; Dewey, 1925/1971). Communication is the basis for experience, and it is through language that we create meaning (Dewey, 1925/1971). Language is viewed not as a description of things but as action and as (re)creating the social world. The focus of this study is on how the role of the teacher in student health work is constructed through language. The social world is constructed by the meanings that people assign to symbols (Blumer, 1969; Charon, 2010). The concepts of ‘the role of the teacher’ as well as ‘health’ are viewed as linguistic symbols. The meaning of a symbol is subjective and constructed through social interaction (Blumer, 1969). It also is modified through social interaction and can thus vary depending on, for example, social context, culture, and the historical time period.

Health, as a linguistic symbol within the framework of this study, is viewed as an integrated part of human life and as more than the absence of ill health (Eriksson, 1996). It is not a dichotomy between health and ill health but rather relative to the individual, the situation, and the culture. Health is viewed holistically and as dependent on social processes, (re)created through social interaction between individuals (Eriksson, 1996; Mead, 1972). Health is connected to well-being, and like health in Eriksson’s view, well-being is not a fixed state, but a process influenced by individual perception, social context, and interpersonal relationships (Dodge et al., 2012). Health and well-being are interdependent: health provides the capacity to experience well-being, while well-being supports behaviours and attitudes conducive to maintaining health (Steptoe et al., 2015). The construction of both health and well-being as contextually dependent and socially mediated enables a conceptual bridge between the two.

For example, Mead’s (1972) symbolic interactionism underlines that meaning emerges through social interaction, implying that experiences of both health and well-being are not only subjective but also socially negotiated. Well-being, then, is not merely a personal feeling of life satisfaction but a socially situated experience, resonant with Eriksson’s notion of health as being (re)created in relationships.

2.2. Previous Research

How schools work with student health has been empirically explored, but teacher involvement in this work and the student perspective both need further investigation. Much research into the role of the teacher in student health care has focused on programmes and initiatives. Although some research has concerned teacher involvement in programmes targeting physical activity (Barcelona et al., 2022) and nutrition (Bergling et al., 2022), most studies have addressed programmes targeting student mental health (Askell-Williams & Cefai, 2014; Daniele et al., 2022; Graham et al., 2011).

A recurring theme in previous research about the role of teachers in working with student health is that teachers often perceive themselves as key actors in identifying and responding to students’ mental health concerns. Various studies highlight the multiple roles that teachers adopt in this work. Despite differences in context and educational level, studies such as Douwes et al. (2024), White and LaBelle (2019), and Berg et al. (2024) provide similar accounts of these roles.

The studies identify a range of teacher roles, such as the awareness raiser (Douwes et al., 2024), relationship builder (Berg et al., 2024), first responder, and empathic listener (White & LaBelle, 2019). These roles centre on recognising and supporting the individual student, with teachers describing efforts to create environments where students feel safe expressing their emotional state, while carefully navigating the balance between care and professional distance.

In the role of referrer (Berg et al., 2024) or referral source (White & LaBelle, 2019), teachers primarily see themselves as recipients of information or signals concerning students’ mental health, with the main responsibility of referring students to appropriate professional services. In contrast, the role of bystander (White & LaBelle, 2019) reflects a choice not to engage in mental health-related matters, often due to concerns about overstepping professional boundaries or acting inappropriately.

In research regarding the students’ perspectives, students perceive the actions of the teacher as crucial for their health (Maelan et al., 2020; Rosvall, 2020). Different types of classroom participation in which students have influence over their situation are regarded as beneficial for their health (Hammerin et al., 2018; Warne et al., 2017). A sense of safety provided by the teacher and trusting relationships with teachers are additional aspects that students highlight as health promoting (Kostenius et al., 2020).

Forsberg et al. (2021) studied the student perspective on school climate and found that teaching style is one reason for disruptive behaviour. How teachers respond to this behaviour affects students’ sense of safety and the school climate. The students preferred and asked for teachers who were caring and kind but who could also maintain classroom order. In line with this, research by Douwes et al. (2023) shows that students view well-being as a positive and holistic construct. While they distinguish between student life and other life domains, they consider all domains—academic, social, and personal—as interconnected and essential to their overall well-being as students. This insight urges educational institutions to adopt broader, student-informed perspectives when developing policies and practices to support student well-being and learning environments.

Both Maelan et al. (2020) and Kostenius and Nyström (2020) have studied the student perspective on health and found that students view academic support from teachers and how their academic needs are handled as important for their health. Other important health factors were how teachers responded to students’ school-related stress and how they engaged with the students (Maelan et al., 2020).

The role of the teacher and the boundaries of the teaching profession have been explored internationally (Bouckaert & Kools, 2018; Bray, 2022; Shavard, 2023) and in the Swedish context (Gardesten et al., 2021; Lindqvist et al., 2019). When studying the teaching profession in connection to student health, Shavard (2023) explored the boundaries of the teacher’s responsibility for student well-being in primary school from the perspective of teachers. The findings reveal ambiguity, stress, and frustration connected to defining the boundaries of the teaching profession.

Regarding research involving the high school level, Askell-Williams and Cefai (2014) found that teachers feel hesitant regarding their competence to promote student mental health. Phillippo and Kelly (2014) found that although high school teachers will encounter student mental health issues, they will not necessarily address them. This outcome is similar to the findings of Ekornes (2015), who showed that teachers perceive their work in student health care to consist of identifying problems and referring students to the student health services.

Not many Swedish studies on student health care have been carried out since the Swedish Education Act came into force in 2010, and those that have been completed focus mainly on management staff, the school as an organisation, special initiatives, or the student health staff (e.g., school nurses, school doctors, school psychologists, counsellors) (Hjörne & Säljö, 2014; Odenbring, 2019; Skott, 2022). However, in a recent study, Hammerin et al. (2023) examined local Swedish documents in which student health care is planned, with a focus on the role of the teacher. The results show the teacher as largely being omitted from the documents or not being given any concrete role or responsibility. Hammerin and Basic (2024) have explored the teachers’ perspective of how they work with student health. The teachers report that helping students succeed academically and creating good relationships with students represent working with student health. Furthermore, the analysis shows that giving social pedagogical recognition to the students and recognising their social and academic identities is significant for success when working with student health. How the role of the teacher is defined by students has not been explored empirically, to our knowledge.

2.3. The Swedish Context

Since the 1980s, the Swedish educational system has dramatically reformed (Lindensjö & Lundgren, 2014; Ringarp, 2011). With this reform, conditions have changed for teachers in several areas, including student health care. In the early 2000s, the terms ‘student health care’ (elevvård) and ‘school health care’ (skolhälsovård) were replaced by the term student health work.

This replacement signalled a change in the student healthcare policy from a pathogenic perspective focused on deficit and illness to a salutogenic perspective focused on ability and well-being. The shift, combined with the reciprocal relationship between health and learning (Gustafsson et al., 2010) highlighted in Swedish school policy, placed student health work within the responsibility of the teacher.

In an amendment in The Education Act (SFS 2010:800) from July 2023, there is an emphasis on cooperation between student health services and teachers. This emphasis represents the first time teachers are mentioned in relation to student health work in a Swedish legislative document. Furthermore, a guidance document issued by the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and The Swedish National Agency for Education (2016, p. 27) stresses that ‘Student health work is carried out in all school settings, not least in the classroom where the teacher plays a central role’ (see also the Swedish Schools Inspectorate, 2021). However, what this work involves needs to be defined in practical terms in the individual school.

Traditionally, working with student health is a task for the student health services (Hammarberg, 2014). This professional group focused on the students typically comprises a doctor, nurse, counsellor, psychologist, and special educational needs coordinator. However, the teacher has come to play a bigger part in student health work in Sweden, at least on a policy level. This article explores what this larger role could entail in school practice.

An important backdrop to the policy changes is the ongoing debate regarding the boundaries of the teaching profession. Some have emphasised clear boundary-setting and a clean-up (renodla) of the teaching profession (Gardesten et al., 2021). The aspects of the profession that are considered more ‘social’, such as working with student health, have been questioned by both researchers and the Swedish teachers’ union (Kariou et al., 2021; Sveriges lärare, 2023). Rhetoric has focused on ‘allowing teachers to be teachers’, meaning that they only should teach and not carry out other tasks such as administrative tasks or student health work. New professional groups such as social pedagogues and ‘super mentors’ are created as a way for teachers to focus on teaching and diminish the so-called ‘social aspects’.

While existing research has established the increasing role of teachers in student health, particularly mental health, most of these studies focus on teachers’ self-perceptions or programmatic interventions (Askell-Williams & Cefai, 2014; Douwes et al., 2024; Berg et al., 2024). These studies tend to highlight multiple teacher roles such as first responder, referrer, and empathic listener, often emphasising mental health from the teachers’ viewpoint. However, there remains a notable gap regarding the students’ perspectives on the teacher’s role in their health care, which is essential given the importance of participation and empowerment in health promotion (World Health Organization, 1998).

Moreover, much of the existing literature is situated within healthcare disciplines rather than pedagogical research (Ragnarsson et al., 2020), potentially limiting the integration of student health into everyday pedagogical practice. Our study seeks to address this gap by explicitly framing student health work as both a pedagogical and healthcare issue. This perspective aligns with international concerns about holistic health in education and contributes to a deeper understanding of how teachers’ roles are socially constructed within the classroom context through student–teacher interactions.

Additionally, the Swedish context, with policy shifts placing increased expectations on teachers regarding student health (SFS 2010:800; Swedish National Agency for Education, 2023), provides a unique backdrop to explore whether such policies translate into altered teacher roles as perceived by students. By focusing on student voices, which are underrepresented in the field, our study offers a novel contribution that bridges gaps between policy, pedagogy, and health promotion.

3. Materials and Methods

This study employed a qualitative, exploratory research design (Creswell, 2019), grounded in an interpretivist paradigm (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018), to explore students’ perspectives on the role of teachers in working with student health.

The present study adopts a qualitative case study approach, which is particularly well suited for exploring complex social phenomena in real-life settings (Yin, 2018). In line with the interpretivist tradition (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018), this approach prioritises participants’ subjective experiences and the contextual meanings they attach to them, making it especially appropriate for exploring how students understand the role of teachers in relation to their health.

Case studies are valuable in educational research because they allow in-depth examination of processes, relationships, and contextual factors that would be difficult to capture using quantitative methods (Merriam, 1998). This study focuses on two high schools, which are treated as bounded cases within which student perspectives were explored. The aim is not generalisability in a statistical sense, but rather analytical generalisation (Yin, 2018), offering transferable insights grounded in richly described empirical data.

The use of interviews aligns with the strengths of qualitative research in uncovering nuance and lived experience (Creswell, 2019). By focusing on student voices, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how school health work is enacted and experienced from the perspective of those most directly affected.

The design was flexible and adaptive, allowing methodological decisions to evolve in response to ethical and practical considerations (Maxwell, 2013). Emphasis was placed on capturing the subjective experiences of students and understanding how they make sense of the concept of health in school settings in relation to teachers.

A criterion-based sampling strategy was employed (Patton, 2015), with a single yet inclusive criterion: participants had to be enrolled in one of two upper secondary schools involved in the study. Both schools, here referred to as School A and School B, are large, municipality-run institutions with approximately 1500 students each. A total of 34 students (19 girls and 15 boys), aged 16 to 19, participated. Twenty-four participants were from School A and ten from School B. Participants attended either vocational or university preparatory programmes and had diverse ethnic and academic backgrounds. This information was given voluntarily by the participants. No other background data were collected prior to the interviews, except for students’ programme and year level, to reduce the influence of preconceptions.

Students were recruited through two primary methods. In the first, the researcher attended lessons, introduced the study, and invited participation. Interested students were interviewed in a quiet, private location they found comfortable. In the second method, teachers or school mentors approached students and, upon student agreement, passed their contact information to the researcher. Interviews were then scheduled via text message. All participants received written and oral information about the study and gave informed consent. Special care was taken to ensure students fully understood their participation was voluntary and could be withdrawn at any time.

Data were collected through semi-structured, exploratory interviews (Cohen et al., 2018), allowing students to express their own meanings of health without being constrained by a predefined definition. Instead, the concept of health was discussed using more accessible language—“feeling good” in school. In line with Eriksson (1996), we interpreted “health” as the objective, external perspective, and “feeling good” as the subjective, internal experience. An interview guide with eight open-ended questions was used.

Students could choose to be interviewed alone, in pairs, or in focus groups. As a result, the data collection included four individual interviews, five pair interviews, and six focus group interviews. After the first five sessions with a total of eleven students, the interviews were found to lack variation and occasionally became overly personal, posing ethical and methodological challenges. In response, the data collection process was adjusted.

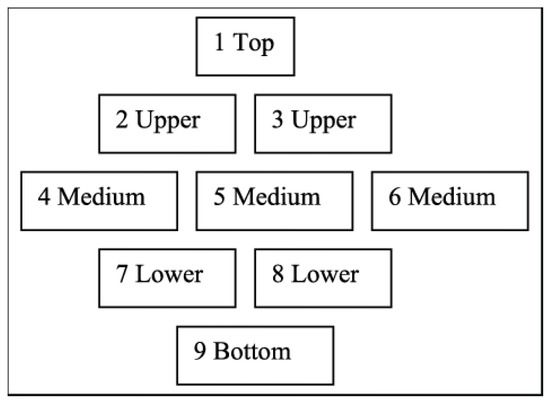

To support more structured and reflective discussions, a stimulus-based technique called Diamond Ranking was introduced (Rockett, 2002) (Figure 1). This method was used in the remaining ten interviews. Based on insights from the initial five interviews, during which only the interview guide focusing on teachers and students “feeling good” was used, nine images were carefully selected to represent various aspects connected to student health in school. Examples included an image of a classroom with students and a teacher, and a hallway with lockers.

Figure 1.

The Diamond Ranking empirical material from all 15 interviews was used in the analysis.

Students were asked to rank these images in the shape of a diamond, with the most important image at the top and the least important at the bottom. The purpose was not the ranking itself, but the conversation and negotiation it stimulated. This technique encouraged students to articulate and reflect upon their views in a less emotionally charged way, thereby addressing earlier ethical concerns.

The subsequent ten interviews began with the same interview guide as the previous five, then proceeded to use The Diamond Ranking. It soon became clear that the method did indeed enrich the material and yield a greater variation and depth. The students interpreted the pictures in different ways, focused on different aspects, and the discussions became more general and less personal. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Here, participants have been given fictional names to ensure confidentiality (Cohen et al., 2018).

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Approval No. 2021-05748-01). Participation was voluntary, with clear communication about anonymity, confidentiality, and the right to withdraw. Careful attention was paid to ensuring informed consent and creating a safe, respectful environment for the students.

Data were analysed using qualitative content analysis as described by Graneheim and Lundman (2004) and Hsieh and Shannon (2005). This method is based on a systematic reading of the interview transcripts and requires both creativity and an adherence to the data. The foundations of pragmatism and symbolic interactionism worked as analytical starting points. The initial coding and thematic development were carried out by the first author. Throughout the process, the second and third authors contributed through regular discussions, critical questioning, and review of the developing interpretations. This collaborative approach supported a thorough and reflexive analytical process.

The relevant data were coded based on the aim and research question, and the codes were placed into categories based on interpretation of similarities within the group and differences between the groups. Subsequently, the groups were named based on an abstraction of the content. Throughout the process, we returned to the data to verify, refute, or clarify.

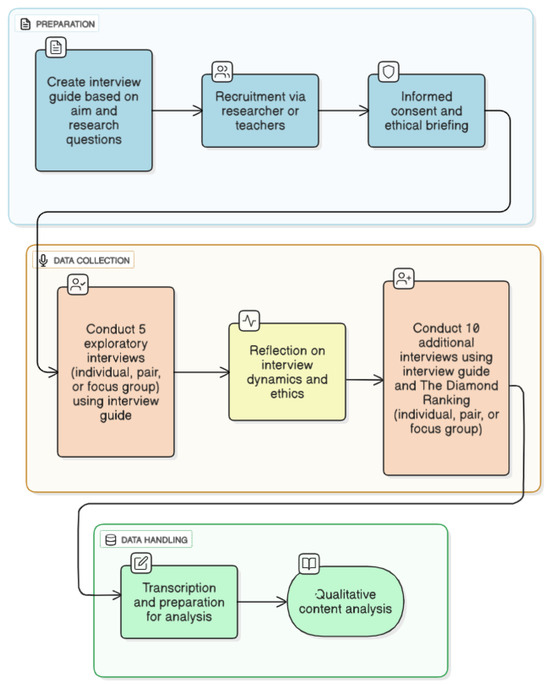

The analysis was an iterative process in which the connection to inclusive teaching highlighted below in the discussion section was made during the last stages of the analysis. A flowchart of the methodological phases can be found below (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of methodological phases.

4. Results

Four main themes were developed that related to different aspects of the role of the teacher in working with student health. These themes are as follows: (1) a creator of joyful learning, (2) a creator of a sense of control, (3) a spreader of happiness, and (4) a creator of feeling valued.

4.1. A Creator of Joyful Learning

The first theme concerns how a teacher can create joyful learning, which in turn affects student health in a positive way. The term ‘joyful learning’ refers to feelings of enjoyment and a desire to learn. According to the students, when teachers mix lectures with group discussions, competitions, and individual work, the lesson is perceived as joyful, and they feel good. One student described what makes him feel good in the following way:

They vary how they teach. Maybe sometimes they use PowerPoint, maybe sometimes you talk in groups and discuss.(Boy, School B, focus group interview)

In the quote above, the student describes actions by the teacher (‘They vary how they teach’). In describing an understanding of the role of the teacher, the quote above reveals the student’s meaning-making of the teacher’s actions and how the varied teaching methods applied make him feel about learning. Joyful learning and its connection to the encouragement of health become part of the social construction of the teacher’s role as a teacher. The teacher’s creating of joyful learning makes sense to the students and therefore makes them feel good. In a pragmatic and symbolic interactive sense, the language used comes to represent the symbolic value of the teacher’s actions and therefore becomes the premise on which the social interaction in the classroom takes shape: a creating and recreating of the social world of the classroom (Dewey, 1925/1971).

The students also describe that participation is a way for the teacher to create joyful learning and affect their health in a positive way. When asked what it means to participate, the students recount that it is about being active and engaged, for example, by discussing subjects that are important to them. One student, talking about lessons that make students feel good, explained the following:

Right now we are working with crime and punishment. It is very interesting, a lot of us think so. Then discussing is fun.(Girl, School A, couple interview)

Participation in discussions here becomes a communicative action on behalf of both the teacher and the students, one that reveals the basis for experience when it comes to the creating and recreating of the teacher’s role because language becomes pivotal in the process. In other words, the discussions delineated as part of the description of the teacher show how language facilitates the meaning-making in and of the social world of the classroom.

What the student is describing is the joyful learning occurring when the teacher picks a topic and an activity that engage the students. The students in the couple interview excerpted above moved on to describing how these discussions could have positive effects both inside and outside of the classroom and lead to further discussion. According to the students, they then get to know each other better and develop stronger social bonds and begin speaking to students to whom they do not normally speak, as exemplified below:

And then the discussions can continue outside of the classroom. I mean, it becomes a topic many of us talk about later. (…) It can be with someone who has the same opinion as me but I don’t usually hang out with (…) So it can have a big impact on the class and I think that is great.(Girl, School A, couple interview)

The making sense of the discussions and the joyful learning that they invite evoke in the students an interest in further social interaction. Here, the meaning-making of the social world of the classroom becomes an example of how the students re(create) the social world, begun through the teacher’s actions, outside of the classroom as well—something that they say benefits their health.

For the students, participation also means the ability to influence the lesson content, which according to them leads to joyful learning. One student recounted how he experiences joyful learning when teachers ask the students what they want to do and then lets all of the students have an influence, not only the majority:

That it is varied, and the teachers ask, ‘What do you want to do?’ Because everyone is different in what they want to do. And then not only do what most of the students want but to vary between the suggestions that come up during the semester. Provided that it is in accordance with the curriculum, of course.(Boy, School B, individual interview)

Furthermore, it is important to the students that the teacher can teach in what the students call a ‘good’ way. What that means for them is that the teacher can explain a concept in a way that everyone understands. This definition is exemplified by one student in the following quote:

I have had a couple of teachers who really explained well … who made you want to learn more.(Boy, School A, individual interview)

In his experience, teachers who explain well make him want to learn more, thus creating joyful learning and impacting his health in a positive way. Other aspects of explaining in a way that creates joyful learning that the students disclosed include patience when students do not understand and not showing anger or frustration. For them, it is important that teachers show an understanding of different ways and different paces of learning.

Here, it becomes apparent that the symbolic interaction with regard to the teacher’s role as a creator of joyful learning is a subjective experience on behalf of the student and is modified in a way that also positively affects the student’s health.

4.2. A Creator of a Sense of Control

The second theme concerns how the teacher can create a sense of control for the students. This outcome is achieved by giving information, being clear, and providing structure. These are examples of meaning-making in relation to the linguistic symbol ‘control’. The connection between the role of the teacher as a creator of a sense of control and health is again exemplified by teacher actions; in our material, the students relayed experiences of stress and confusion regarding their schoolwork and explained that structure and clarity make them feel good. They also describe how their health is affected negatively by not understanding or knowing what to do, whereas clarity and knowing what is expected of them have positive effects on their health.

According to the students, clear information is a way for the teacher to contribute to the students’ sense of control. One student expressed frustration and stress about not finding the information he needs. He continued to explain as follows:

Because if you don’t get enough information, or information you understand, it is stressful for the students. They don’t know what to do, where to go and stuff like that. Information is an important thing. It is the little things that make the biggest difference.(Boy, School A, couple interview)

The boy begins by highlighting how insufficient information leads to stress. He continues by describing that information is important and that to gain a sense of control and feel good, little things can make a big difference regarding information.

Another way that the students described that a teacher can contribute to a sense of control is by creating structure. This structure concerns both lessons and the overall school situation. One student said that everything concerning school and health is really about structure, which is exemplified in the following quote:

If you are to feel good and you know, go to class, they should make it so everything feels structured. Like, everything is about structure really.(Girl, School A, focus group interview)

In the students’ accounts, there are many examples of structure and on different levels. They explained how they have received help with structuring their workload when falling behind and how to prioritise which tasks to do first. Structure for them also means that the teacher has a clear lesson plan that is conveyed to the students and that they know how to begin and structure a written task.

Providing clear information and structure creates a sense of control that makes the student feel calm. During a group interview, the question of how teachers can make students feel good in school was asked. One student promptly answered, ‘By being well planned and structured. Good lesson plans and …’ ‘So you feel calm about the plan and structure’, another student added (Boys, School A, group interview).

The language that the students used to (re)create the symbolic value of control when describing the teacher as a creator of control becomes relevant in terms of both positive and negative meaning-making. The teacher’s actions are viewed and understood as either reinforcing control and structure, as when the students describe the teacher’s structuring the workload and helping students to prioritise, as well as conveying clear lesson plans, or as weakening a sense of control when these supports fail to materialise.

4.3. A Spreader of Happiness

The third theme concerns how teachers spread happiness by exuding happiness and using humour in the classroom, in turn making the students feel good. The students describe that when the teachers spread happiness in the classroom, it makes the students feel happy too. When the teachers exude a positive and happy attitude, the students describe it as ‘contagious’ and they feel happy as well, even if they entered the classroom feeling low or sad. One student reflected on what makes him feel good at school and talked about friends. He continued, ‘But the teachers are also important. If they spread happiness, it spreads to us’ (Boy, School A, individual interview).

According to the students, the teacher can spread happiness by encouraging them and giving positive feedback on their schoolwork. Another way they relayed this was for the teacher to use humour and have fun with the students. One girl described this experience in the example below. She had previously talked about why some teachers make her feel good in school while others do not:

To be able to have fun together. That is really … I mean, I don’t know why but humour can be really important actually.(Girl, School B, focus group interview)

Having fun and laughing together was a recurring concept in the students’ descriptions. When teachers contribute to a relaxed atmosphere and joke with them, the students feel happiness, which in turn affects their health in a positive way. One student talked about his social science teacher with whom he could joke and have fun:

You can joke about the same things. With my social science teacher, for example, I can joke about political stuff, and I laugh and he laughs.(Boy, School A, individual interview)

The students express their understanding that teachers are not always going to be in a good mood and enjoying their job, but the students say that they still appreciate if teachers try. In this, they view the teacher as a catalyst whose energy and mood are contagious and affect the students, as one girl explained in the following quote:

That they still try to be happy and positive, you know …. Because it is infectious for the students.(Girl, School A, couple interview)

Within the theoretical underpinnings of this study, if we are to understand the social world as constructed through the meaning we assign to its symbols (Blumer, 1969; Charon, 2010), the teacher as a ‘spreader of happiness’ represents a symbol to which the students assign meaning. Within the social world of the classroom, the teacher’s happiness and positive energy construct the feeling good of the students, enthuse them, and make them happy. Thus, meaning-making on behalf of the students in describing the teacher as a spreader of happiness becomes in itself an action towards learning and health because the social interaction between teacher and student facilitates this contagiousness.

4.4. A Creator of Feeling Valued

The fourth theme concerns how the teacher can make the students feel valued by viewing them as individuals and caring about them. The students recount that they feel good when teachers show interest in different aspects of their lives that do not necessarily pertain to school. They describe it as negative to be seen ‘only’ as a student and express a wish to be seen as people with a life and a value outside of school.

One student talked about a teacher who makes her feel good. In the following quote, she exemplifies the students’ wish to be seen as a person:

I think it’s good if you don’t see your student as just a student. I mean, as a person as well and she does that.(Girl, School A, couple interview)

Being seen as a person is thus one way that the students make meaning of ‘feeling valued’. The students express that when teachers talk to them about aspects of their lives that are important to them, they feel seen as a person and valued as such. They give examples such as sports, noticing knowledge progression, or changes in students’ family situations. One student described it in the following way:

That they show that they know who you are and not only have maths just to have maths. That they show that they care about your life outside of school, too.(Boy, School A, couple interview)

According to the students, they feel valued when teachers care about them. One way that teachers can do this is to acknowledge if a student does not appear to be feeling well. When discussing what it means for a teacher to care, one boy explained the following:

‘Did something happen or are you just tired? Did you not sleep well?’ Or something like that. Just check in, see how you are doing. I think that is important, that they care about the students.(Boy, School B, focus group interview)

Other examples students gave of how teachers show caring and make them feel valued include reminding students about schoolwork that is due, asking where they were if they have been absent, and helping students resolve conflicts. According to the students, this kind of interest in turn affects their health in a positive way.

The theoretical starting points of this study, as shown above, come to the forefront in the understanding of the teacher as a creator or giver of value. Both the teacher’s and the students’ knowing and understanding of the social world and interaction of the classroom become synonymous with the agents’ actions. The teacher’s role as a symbol of value, both in the action of giving and in the student’s action of receiving, enables the interaction within the classroom; an interaction in turn that promotes both learning and health, according to the students. Feeling valued and important thus becomes a meaning-making symbolic interaction between teacher and students.

The four roles of the teacher that the students in this study described are constructed from the students’ experience in order for them to transact the social world of the classroom to meet their learning and health needs. This transaction in turn is possible only through the action enabled by the communication, or linguistic turn, that is used in both the describing of the teacher and in the teacher’s communicating of actions. Thus, with regard to the overall aim of this study—to understand the teachers’ work with student health from a student perspective—the work that the teacher does carries pragmatic and symbolic interactionist underpinnings.

5. Discussion

In this article, the role of the teacher in student health work has been explored from a student perspective. The results show that the students emphasise (1) joyful learning, (2) a sense of control, (3) spreading happiness, and (4) feeling valued as linguistic symbols that they use to connect the symbols ‘the role of the teacher’ and ‘health’. The students’ meaning-making regarding these linguistic symbols consists of actions taken by the teacher. These actions can be seen as representing ‘health’ in the school context from the students’ perspectives. A conclusion can thus be made that the four themes presented in the results and analysis section can be regarded as the students’ perception of the role of the teacher in student health work.

The analysis of the empirical material using symbolic interactionism and pragmatism offers an opportunity to explore important didactic aspects of meaning-making regarding the role of the teacher in student health work. A pedagogically and didactically competent teacher who varies teaching methods, includes and engages students, and uses their social and pedagogical experiences in the teaching situation is considered a teacher working with student health. Based on the results, the role of the teacher in student health work is in acting, not being. It is a constant (re)creation through interaction.

The four themes mirror four different aspects of health. The type of health the students bring to light does not centre around illness or offer a biomedical perspective on health; rather, it is health in a broad and holistic sense. For the students, health in the context of school is connected to being seen and valued as well as feeling happy, experiencing meaningfulness, and control.

5.1. The Teacher as a Creator of Joyful Learning

The students’ descriptions of joyful learning underscore the teacher’s role in making lessons engaging, varied, and understandable, thereby promoting student health through positive emotional experiences. This aligns with previous research emphasising the importance of teaching style and engagement for student well-being (Forsberg et al., 2021; Maelan et al., 2020). According to Forsberg et al. (2021), caring and kind teachers who manage classroom order effectively contribute to a positive school climate, which supports students’ sense of safety and belonging.

From the theoretical perspective of symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1969), joyful learning is not merely a byproduct of teaching, but a symbol constructed and negotiated between teacher and student through interaction. The teacher’s pedagogical choices act as communicative acts that generate shared meaning and foster a social environment conducive to health. This dynamic process reflects Dewey’s (1925/1971) pragmatic view that learning and experience are inseparable, and that joy in learning arises from meaningful interaction.

Moreover, joyful learning relates closely to the relational dimension of inclusive teaching (Molbaek, 2018), where positive social bonds and engagement are key. This demonstrates that creating joy in learning is a crucial pathway through which teachers contribute to student health, integrating didactic competence with relational care.

5.2. The Teacher as a Creator of a Sense of Control

The students’ emphasis on the teacher’s role in creating a sense of control highlights the importance of structure, clarity, and predictability in supporting student health. From the students’ perspective, when teachers provide clear information, organise lessons effectively, and support students in managing their workload, it fosters feelings of security and well-being. This aligns with the theoretical underpinning of symbolic interactionism (Blumer, 1969; Charon, 2010), which frames ‘control’ as a linguistic symbol constructed and continuously (re)created through social interaction. The teacher’s structuring actions function as meaningful symbols that students interpret as care and recognition within the school’s social world.

Following the pragmatic perspective (Dewey, 1925/1971; Biesta & Burbules, 2003), the experience of control is not a fixed state but an outcome of ongoing interactions and communication between teachers and students. Language and action here are inseparable; through verbal and nonverbal communication, teachers shape the students’ experience of control as part of their overall health. The fluidity of the symbol ‘control’ also means its meaning may vary depending on individual needs, cultural context, and the immediate school situation, as described by Eriksson (1996).

Empirical research supports this view, with studies such as Douwes et al. (2024) and White and LaBelle (2019) recognising teachers as awareness raisers and first responders who help students navigate emotional and academic challenges by providing clear guidance and structure. Moreover, this theme corresponds with Molbaek’s (2018) framing dimension of inclusive teaching, which underscores the importance of clarity about learning goals and activities—a pedagogical strategy that also promotes student well-being.

Therefore, the teacher’s role as a creator of a sense of control should be understood as a dynamic, interactive process where language and actions symbolically communicate support, enabling students to feel valued and secure. This relational and didactic function is integral to student health, emphasising that health and learning are deeply interconnected within the social fabric of the classroom.

5.3. The Teacher as a Spreader of Happiness

The theme of spreading happiness reflects the relational and emotional support that students associate with teacher involvement in health work. Previous studies emphasise the teacher’s role as a relationship builder and empathic listener, creating environments where students feel emotionally safe and cared for (Berg et al., 2024; White & LaBelle, 2019). The students’ accounts of teachers spreading happiness through humour and positive interactions resonate with these relational roles.

In terms of theory, this spreading of happiness can be understood as a symbolic act within the classroom’s social world (Blumer, 1969), where positive emotions serve as symbols of inclusion and belonging. Pragmatism (Dewey, 1925/1971) underscores the continuous and emergent nature of these experiences; happiness and laughter are not fixed states but ongoing actions that help (re)create the social world of the classroom. This aligns with the symbolic interactionist view that meanings, including those related to health, are constructed and reconstructed through social interaction. Thus, spreading happiness is an essential, active component through which students and teachers collaboratively produce a healthy educational environment.

This finding corresponds with the relational dimension of inclusive teaching (Aspelin et al., 2021; Molbaek, 2018), where communication, participation, and social bonds are central. Happiness thus emerges as a key social symbol reflecting health-promoting teacher–student interactions.

5.4. The Teacher as a Creator of Feeling Valued

Feeling valued is a critical dimension of student health identified in this study and supported by previous research showing that trusting relationships and caring teacher behaviours promote well-being (Kostenius et al., 2020; Maelan et al., 2020). The students emphasise teachers’ recognition of their individuality and social identities as fundamental to feeling respected and supported.

From a symbolic interactionist perspective (Blumer, 1969), the teacher’s recognition is a communicative act that constructs the symbol ‘feeling valued’ within the classroom’s social world. This dynamic process reflects the ongoing (re)creation of social meaning through interaction, emphasising the importance of relational care in health.

This theme also ties directly to the social pedagogical recognition highlighted by Hammerin and Basic (2024), where teachers’ engagement with students’ social and academic identities is essential for promoting health. It underscores that the teacher’s role in student health transcends mere academic support, encompassing holistic recognition of the student as a person.

One tendency we noted was that students expressing school challenges tended to stress creating a sense of control and making students feel valued as relatively more important roles. In turn, students who expressed succeeding in school emphasised joyful learning to a greater extent. This divergence could suggest the need for different roles to be in the forefront for different students even though they were all deemed important.

What students appear to be asking for is that their health be supported through education rather than being educated about health. A possible reason for teachers’ hesitancy in working with student health, as shown in Askell-Williams and Cefai (2014), Phillippo and Kelly (2014), and Ekornes (2015), could be that working with student health is perceived as education about health and needing to have special training in health. That is not what our results show. Instead, the students are asking for actions that can be considered part of the teaching profession.

While the student perspective aligns closely with the concept of inclusive teaching, this convergence also brings to the surface important tensions within the teacher’s role in student health work. On one hand, framing student health work as an extension of inclusive pedagogy may help teachers feel more competent and comfortable, reinforcing familiar professional boundaries. On the other hand, this framing risks oversimplifying the complex and sometimes conflicting demands placed on teachers—such as balancing emotional support with maintaining professional distance, or navigating institutional expectations that may prioritise academic outcomes over well-being. These tensions challenge traditional educational norms that often compartmentalise teaching and health promotion as separate domains. Our findings suggest that teachers are simultaneously expected to embody multiple, sometimes contradictory roles: empathic caregiver, disciplinarian, academic instructor, and referral agent. This complexity calls for a more nuanced understanding of teacher identity in contemporary education, one that recognises how these competing demands may create stress and ambiguity for teachers, as documented in previous research (Shavard, 2023). Thus, while student voices affirm the importance of relational and didactic competencies, they also highlight the need for systemic support and clearer role definitions to reconcile these inherent tensions.

6. Conclusions

Based on these findings, it can be concluded that the student perspective on the teacher’s role in student health work closely parallels the role of the teacher in inclusive teaching. This alignment supports the study’s theoretical underpinnings rooted in pragmatism and symbolic interactionism, framing inclusive teaching as a form of meaning-making through specific actions and social interactions within the classroom. In this view, the teacher’s work with student health is not a separate or novel task but an inherent aspect of their professional role enacted through everyday pedagogical and relational practices.

Connecting student health work with inclusive teaching offers a valuable perspective that may help teachers feel more comfortable and confident in their role, rather than perceiving these responsibilities as external or beyond their professional scope. This perspective challenges policy shifts that risk compartmentalising or narrowing the teaching profession by separating social and didactic responsibilities.

The students’ descriptions highlight that didactic elements, what and how teachers teach, are inseparable from relational aspects such as care, recognition, and the building of trust. This interplay calls into question efforts to “purify” teaching by removing its social dimension, emphasising instead the necessity of a social pedagogical perspective to fully understand the teacher’s role in promoting student health. Such a perspective aligns with previous research showing that supportive relationships and academic engagement are foundational to student well-being (Berg et al., 2024; Kostenius et al., 2020; Maelan et al., 2020).

Moreover, health and learning are mutually reinforcing processes (Gustafsson et al., 2010), making it unlikely that one can be effectively addressed without the other. Therefore, strengthening teachers’ didactic and relational competencies holds promise for enhancing student health practices. Outsourcing the social dimensions of teaching to other professionals risks undermining the holistic nature of education and the essential interactions that create a healthy learning environment.

Ultimately, understanding the teacher’s role in student health through a pragmatic and symbolic interactionist lens, as ongoing meaning-making within the social world of the classroom, illuminates the critical and multifaceted contributions teachers make to both learning and well-being. We argue therefore that developing teachers’ didactic and relational competencies could be a contributing factor to the improvement of student health practices.

7. Limitations and Further Research

Some methodological aspects of this study need to be addressed. The different ways of collecting data (individual, couple, and focus group interviews) can be considered a weakness. However, the process resulted in rich data and strengthened the study ethically because it allowed for the participants to influence the data collection which is, in turn, in keeping with their need to feel some control over an educational situation.

The use of Diamond Ranking enriched the data, but there is always a risk that the pictures will be too leading or limit the discussion. Perhaps other topics would have been discussed had the pictures been different. Even so, the selection of pictures was made based on the first interviews, and the images were open to interpretation.

The limitations of the study notwithstanding, the themes emerging from the data alongside the explanations developed in the discussion relate to universal aspects of teachers’ practices and may therefore be valid in other, similar contexts. Generalisation is not intended by this study; rather, its strength lies in the insights gained from the in-depth, qualitative analysis of rich data. The present contribution to the development of new knowledge has raised questions that can be explored in future research. For example, how do principals regard the role of the teacher in student health work? And how can teachers and the Student Health Services collaborate to promote student health?

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Z.H.; methodology, Z.H., J.W. and G.B.; formal analysis, Z.H., J.W. and G.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.H.; writing—review and editing, Z.H., J.W. and G.B.; funding acquisition, Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by The Skaraborg Institute grant number 20/1041.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (nr. 2021-05748-01).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ethical reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Askell-Williams, H., & Cefai, C. (2014). Australian and maltese teachers’ perspectives about their capabilities for mental health promotion in school settings. Teaching and Teacher Education, 40, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspelin, J., Östlund, D., & Jönsson, A. (2021). Pre-service special educators’ understandings of relational competence. Frontiers in Education (Lausanne), 6, 678793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelona, J. M., Centeio, E. E., Hijazi, K., & Pedder, C. (2022). Classroom teacher efficacy toward implementation of physical activity in the D-SHINES intervention. Journal of School Health, 92(6), 619–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A., Appoh, L., & Orjasaeter, K. B. (2024). The school as an arena for mental health work: Exploring the perspectives of frontline professionals on mental health work in Norwegian schools. Frontiers in Public Health, 12, 1454280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergling, E., Pendleton, D., Shore, E., Harpin, S., Whitesell, N., & Puma, J. (2022). Implementation factors and teacher experience of the integrated nutrition education program: A mixed methods program evaluation. Journal of School Health, 92(5), 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G., & Burbules, N. C. (2003). Pragmatism and educational research. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

- Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bouckaert, M., & Kools, Q. (2018). Teacher educators as curriculum developers: Exploration of a professional role. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(1), 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M. (2022). Teachers as tutors, and tutors as teachers: Blurring professional boundaries in changing eras. Teachers and Teaching, 28(1), 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charon, J. M. (2010). Symbolic interactionism: An introduction, an interpretation, an integration. Prentice Hall. Available online: https://books.google.se/books?id=nW4iAQAAMAAJ (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (2019). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (6th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Daniele, K., Gambacorti Passerini, M. B., Palmieri, C., & Zannini, L. (2022). Educational interventions to promote adolescents’ mental health: A scoping review. Health Education Journal, 81(5), 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2018). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. (1971). Experience and nature (2nd ed.). Open Court. (Original work published 1925). [Google Scholar]

- Dodge, R., Daly, A. P., Huyton, J., & Sanders, L. D. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Douwes, R., Janneke, M., Maria, P. G. H., & Boonstra, N. (2023). Well-being of students in higher education: The importance of a student perspective. Cogent Education, 10(1), 2190697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douwes, R., Metselaar, J., Korpershoek, H., Boonstra, N., & Pijnenborg, G. H. M. (2024). Role perceptions of teachers concerning student mental health in higher education. Education Sciences, 14(4), 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekornes, S. (2015). Teacher perspectives on their role and the challenges of inter-professional collaboration in mental health promotion. School Mental Health, 7(3), 193–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, K. (1996). Hälsans ide (2nd ed.). Liber/Almqvist & Wiksell Medicin. [Google Scholar]

- Erlandson, P., & Karlsson, M. R. (2018). From trust to control—The Swedish first teacher reform. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 24(1), 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, C., Chiriac, E. H., & Thornberg, R. (2021). Exploring pupils’ perspectives on school climate. Educational Research, 63(4), 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, J., McNamara, O., Campbell, A., Howson, J., & Lewis, S. (2008). Partnership, policy and politics: Initial teacher education in England under New Labour. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 14(4), 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardesten, J., Nordänger, U. K., & Herrlin, K. (2021). Scenkonst eller gatuteater? Lärares arbete i relation till struktur, organisering och yrkesgränsernas utsträckning. Nordic Studies in Education, 41(2), 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A., Phelps, R., Maddison, C., & Fitzgerald, R. (2011). Supporting children’s mental health in schools: Teacher views. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 17(4), 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardena, H., Leontini, R., Nair, S., Cross, S., & Hickie, I. (2024). Teachers as first responders: Classroom experiences and mental health training needs of Australian schoolteachers. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, J.-E., Allodi Westling, M., Alin Åkerman, B., Eriksson, C., Eriksson, L., Fischbein, S., Granlund, M., Gustafsson, P., Ljungdahl, S., Ogden, T., & Persson, R. S. (2010). School, learning and mental health: A systematic review. Kungliga Vetenskapsakademien (The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences). Available online: https://www.uppdragpsykiskhalsa.se/stockholmslan/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/KVA_rapport_HL_30mars1.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Hammarberg, L. (2014). Skolhälsovården i backspegeln. Skolverket. Available online: http://www.skolverket.se/publikationer?id=3287 (accessed on 3 November 2024).

- Hammerin, Z., Andersson, E., & Maivorsdotter, N. (2018). Exploring student participation in teaching: An aspect of student health in school. International Journal of Educational Research, 92, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerin, Z., & Basic, G. (2024). Health in everyday teaching practice in Sweden: A social pedagogical analysis of high school teachers’ descriptions. International Journal of Social Pedagogy, 13(1), 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerin, Z., Bergnehr, D., & Basic, G. (2023). A floating concept and blurred teacher responsibilities: Local interpretations of health promotion work in Swedish upper secondary schools. Cogent Education, 10(2), 2287884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjörne, E., & Säljö, R. (2014). Analysing and preventing school failure: Exploring the role of multi-professionality in pupil health team meetings. International Journal of Educational Research, 63, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariou, A., Koutsimani, P., Montgomery, A., & Lainidi, O. (2021). Emotional labor and burnout among teachers: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenius, C., Gabrielsson, S., & Lindgren, E. (2020). Promoting mental mealth in school—Young people from Scotland and Sweden sharing their perspectives. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18(6), 1521–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostenius, C., & Nyström, L. (2020). “When I feel well all over, I study and learn better”—Experiences of good conditions for health and learning in schools in the Arctic region of Sweden. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 79(1), 1788339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindensjö, B., & Lundgren, U. P. (2014). Utbildningsreformer och politisk styrning (2nd ed.). Liber. [Google Scholar]

- Lindqvist, H., Weurlander, M., Wernerson, A., & Thornberg, R. (2019). Boundaries as a coping strategy: Emotional labour and relationship maintenance in distressing teacher education situations. European Journal of Teacher Education, 42(5), 634–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maelan, E. N., Tjomsland, H. E., Samdal, O., & Thurston, M. (2020). Pupils’ perceptions of how teachers’ everyday practices support their mental health: A qualitative study of pupils aged 14–15 in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(7), 1015–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive spproach (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, G. H. (1972). Mind, self, and society: From the standpoint of a social behaviorist. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education (Rev. and expanded ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Molbaek, M. (2018). Inclusive teaching strategies—Dimensions and agendas. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(10), 1048–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odenbring, Y. (2019). Strong boys and supergirls? School professionals’ perceptions of students’ mental health and gender in secondary school. Education Enquiry, 10(3), 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4. uppl.). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Phillippo, K. L., & Kelly, M. S. (2014). On the fault line: A qualitative exploration of high school teachers’ Involvement with student mental health issues. School mental health, 6(3), 184–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragnarsson, S., Myleus, A., Hurtig, A.-K., Sjöberg, G., Rosvall, P.-Å., & Petersen, S. (2020). Recurrent pain and academic achievement in school-aged children: A systematic review. The Journal of School Nursing, 36(1), 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringarp, J. (2011). Professionens problematik: Lärarkårens kommunalisering och välfärdsstatens förvandling makadam. Stockholm. [Google Scholar]

- Rockett, M. (2002). Thinking for learning. Network Educational Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosvall, P.-Å. (2020). Perspectives of students with mental health problems on improving the school environment and practice. Education Enquiry, 11(3), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavard, G. (2023). Teachers’ collaborative work at the boundaries of professional responsibility for student wellbeing. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 67(5), 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skott, P. (2022). Successful health-promoting leadership—A question of synchronisation. Health Education, 122(3), 286–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A., Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2015). Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. The Lancet, 385(9968), 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stillman, J., & Anderson, L. (2015). From accommodation to appropriation: Teaching, identity, and authorship in a tightly coupled policy context. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 21(6), 720–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sveriges lärare. (2023). Sex steg för att du ska hinna vara lärare. Available online: https://www.sverigeslarare.se/rad-och-stod/arbetstid/schemakollen/6-steg-for-att-hinna-vara-larare/ (accessed on 29 February 2025).

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2023). Främja barns och elevers hälsa/Promoting health in children and students. Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/inspiration-och-stod-i-arbetet/stod-i-arbetet/framja-barns-och-elevers-halsa (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare & The Swedish National Agency for Education. (2016). Vägledning för elevhälsa (Guidance for student health services) (3rd ed.). The Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare and The Swedish National Agency for Education. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Schools Inspectorate. (2021). Gymnasieskolors arbete med att främja elevers hälsa (The work of the upper secondary schools to promote student health). Available online: https://www.skolinspektionen.se/globalassets/02-beslut-rapporter-stat/granskningsrapporter/tkg/2021/elevers-halsa-gymnasiet/tkg-gymnasieskolors-arbete-for-att-framja-elevers-halsa_slut.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Tamburrino, I., Getanda, E., O’Reilly, M., & Vostanis, P. (2020). “Everybody’s responsibility”: Conceptualization of youth mental health in Kenya. Journal of Child Healthcare, 24(1), 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warne, M., Snyder, K., & Gadin, K. G. (2017). Participation and support—Associations with Swedish pupils’ positive health. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 76, 1373579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A., & LaBelle, S. (2019). A qualitative investigation of instructors’ perceived communicative roles in students’ mental health management. Communication Education, 68(2), 133–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. (1998). WHO’s global health initiative: Health-promoting schools. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2021, November 17). Adolescent mental health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).