Developing Prosocial Leadership in Primary School Students: Service-Learning and Older Adults in Physical Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Phenomenon of Aging and Intergenerational Service-Learning in Primary Education

1.2. SL and Physical Education: Impact on Students’ Prosocial Attitudes and Civic Values

1.3. Prosocial Leadership Through Intergenerational SL in PE

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Research Design

2.2. The Reflective Journal as a Data Collection Instrument

- Describe a meaningful anecdote or relevant event that occurred during your SL experience with older adults.

- How did you respond to that situation?

- Why or how do you think that situation occurred?

- What did you learn from this event or anecdote that might help you in similar future situations?

2.3. SL Methodology and Implementation Procedure

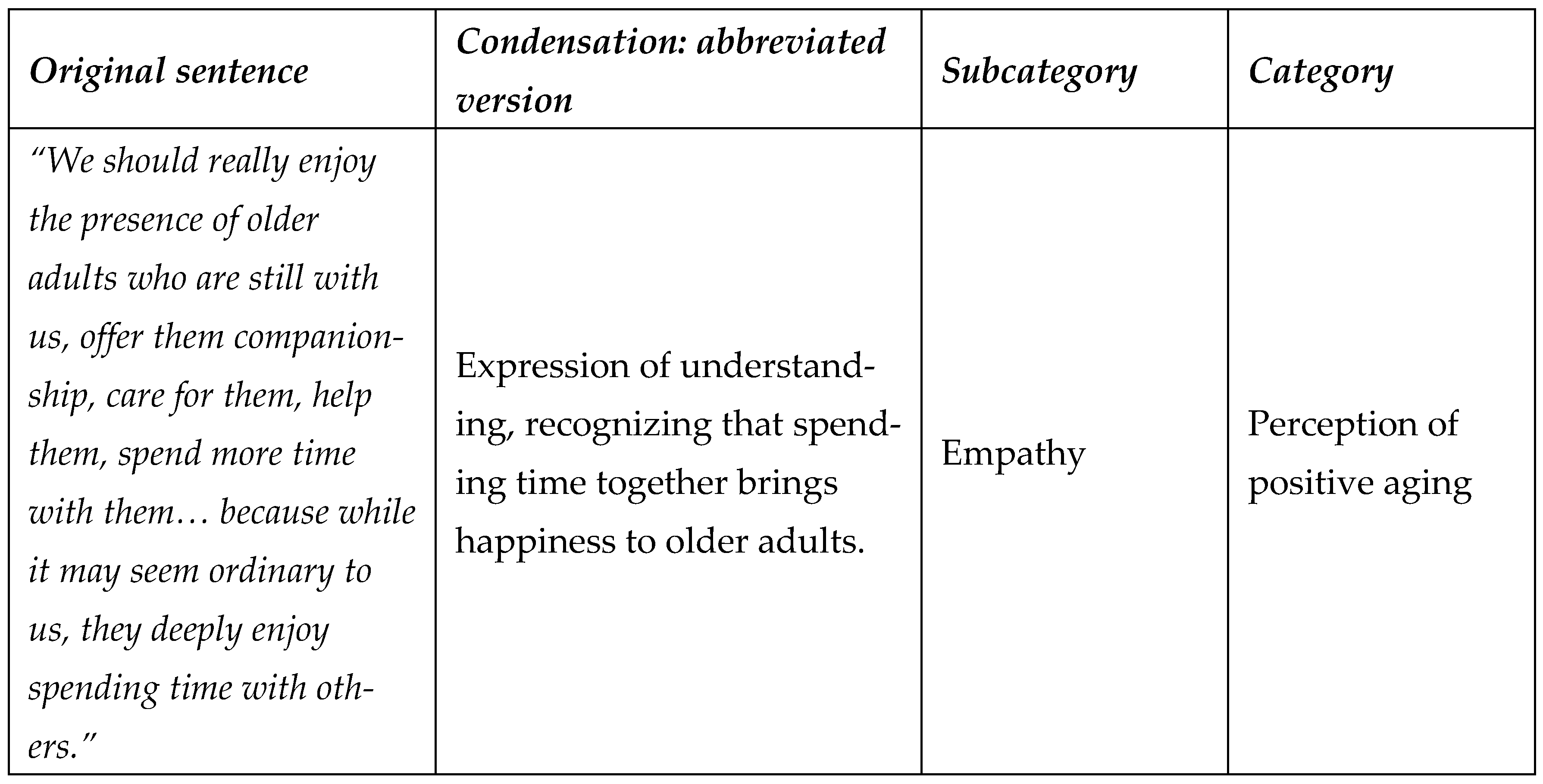

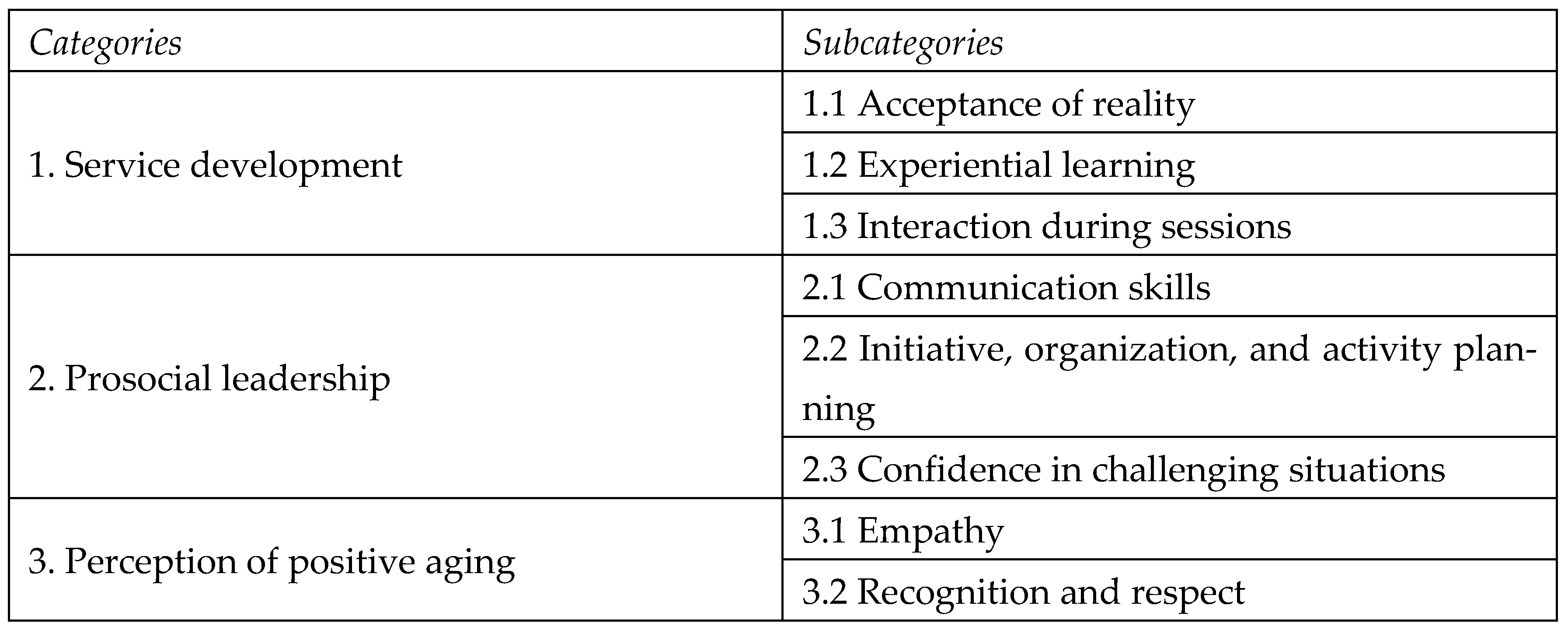

2.4. Data Analysis Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Category: Service Development

- (a)

- Contextualization and planning of the setting and the target population;

- (b)

- Implementation of the SL intervention and data collection from the students;

- (c)

- Evaluation of students’ participation in the program.

AS-6.1: “That you need a lot of patience and love for older people.”

IO-6.2: “That it’s hard to work with older people because they don’t always cooperate.”

CC-6.2: “I learned that no matter what problem they have, an older person needs to feel loved and cared for because they are a person just like me, but with their differences.”

NL-6.2: “ I understand that, as they start losing their memory, they get sad.”

CC-6.2: “This time they responded better to the physical exercises. I barely had to help them. Last time I had to help a bit more. I think they were more eager to participate today, and also seemed a bit happier than before.”

3.2. Category: Prosocial Leadership

SB-6.2: “I have learned to listen to others and express myself better when speaking with older adults, because in my opinion, you need to speak to them more formally than to anyone else.”

EB-6.2: “After explaining to her that I wouldn’t be visiting anymore because the service was ending, I felt sad because I wouldn’t see them again. But what really mattered was that we had been helping each other for many weeks, talking a lot, and that really helped me boost my self-esteem.”

CG-6.1: “I learned that even if my older adult doesn’t attend one day, I can still help others. It was a very fun experience to support people I wasn’t as familiar with.”

IP-6.1: “…when we were doing the stick exercise, he kept saying it was really hard for him, that he was tired, and he kept checking the time.”

AS-6.1: “Instead of doing physical education, he sat down. And thanks to that, I realized that with some people, you need to be more patient.”

3.3. Category: Perception of Positive Aging

AS-6.1: “ My older adult is very funny, kind, and cheerful. She likes to talk a lot and share stories about her life, but she gets sad when she talks about her husband and how he died.”

AS-6.2: “I’ve learned that we need to take care of older people because sometimes they can be like children.”

AD-6.2: “That I want to keep helping people, and that when you do something kind, the world will give it back to you.”

NL-6.2: “That we should always be kind to everyone, especially to older people.”

JS-6.2: “Honestly, I felt like crying, and I speak for myself, but I think the whole class felt the same, that over these months we’ve built a special bond and we’ve all changed a lot for the better.”

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allsop, D. B., Chelladurai, J. M., Kimball, E. R., Marks, L. D., & Hendricks, J. J. (2022). Qualitative methods with Nvivo software: A practical guide for analyzing qualitative data. Psych, 4(2), 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburuzabala, P., Santos Pastor, M. L., Chiva-Bartoll, Ó., & Ruiz-Montero, P. J. (2019). Perspectivas y retos de la intervención e investigación en aprendizaje-servicio universitario en actividades físico-deportivas para la inclusión social. Publicaciones, 49(4), 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango Tobón, O. E., Clavijo Zapata, S. J., Puerta Lopera, I. C., & Sánchez Duque, J. W. (2014). Formación académica, valores, empatía y comportamientos socialmente responsables en estudiantes universitarios. Revista de la Educación Superior, 43(169), 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriaga-Sanz, C., Cabedo-Mas, A., Chiva-Bartoll, O., & Moliner-Miravet, L. (2021). Una mirada comunitaria en la escuela: El diagnóstico del barrio como motor de arranque para proyectos de Aprendizaje-Servicio. Márgenes, Revista e Educación de la Universidad de Málaga, 2(2), 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badenes-Ribera, L., Duro-García, C., López-Ibáñez, C., Martí-Vilar, M., & Sánchez-Meca, J. (2023). The adult prosocialness behavior scale: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 47(1), 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, E. S., Merkebu, J., & Varpio, L. (2022). State-of-the-art literature review methodology: A six-step approach for knowledge synthesis. Perspectives on Medical Education, 11(5), 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berlanga-Fernández, S., Carreiro-Alonso, M. Á., Maestre González, E., Roselló Novella González, A., & Morín Fraile, V. (2021). Análisis cualitativo de los diarios reflexivos de estudiantes de enfermería en trabajos final de grado de aprendizaje-servicio en el distrito III de Hospitalet de Llobregat. ENE Revista de Enfermería, 15(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Billig, S. H. (2022). Service-learning and civic engagement: Enhancing student learning outcomes in K-12 education. Journal of Experiential Education, 45(1), 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Bores-García, D., Hortigüela-Alcalá, D., González-Calvo, G., & Barba-Martín, R. (2020). Peer assessment in physical education: A systematic review of the last five years. Sustainability, 12(21), 9233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgman, C. B., & Mulvaney, E. A. (2016). An intergenerational program connecting children and older adults with emotional, behavioral, cognitive or physical challenges: Gift of mutual understanding. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 14(4), 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calero, J. M. M., Carcelen, R. C. M., & Pérez, J. I. F. (2025). Aprendizaje en educación física: Una propuesta pedagógica desde el enfoque cooperativo. Ciencia Latina: Revista Multidisciplinar, 9(1), 4160–4178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo Varela, D., Losada, S., Eugenio, J., & Fernández, R. (2019). Aprendizaje-Servicio e inclusión en educación primaria. Una visión desde la Educación Física. Revisión sistemática (Service-learning and inclusion in primary education. A visión from physical education. Systematic review). Retos, 36(36), 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Rius, J., Franco-Sola, M., Sebastiani-Obrador, E. M., Figueras-Comas, S., & Lleixà Arribas, T. (2020). Hacia una educación física comprometida con la sociedad. Revista Tándem, 70, 39–43. [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Peris, C., Salvador-García, C., Chiva-Bartoll, Òscar, & Ruiz-Montero, P. J. (2020). Alcance del aprendizaje-servicio en la formación inicial docente de educación física: Una aproximación metodológica mixta (Scope of service-learning in physical education teacher education: A mixed methodological approach). Retos, 37, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G. V., Steca, P., Zelli, A., & Capanna, C. (2006). A new scale for measuring adults’ prosocialness. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 21(2), 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrejón, N. B., & Palacios, M. D. C. D. (2025, May 28–29). Innovación educativa a través del ApS para el desarrollo de competencias en la formación del profesorado de educación infantil y primaria. 9th Virtual International Conference on Education, Innovation and ICT, REDINE, Red de Investigación e Innovación Educativa (pp. 351–352), Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Cebolla-Baldoví, R., & García-Raga, L. (2021). Aprender a manejar los conflictos en las clases de educación física a partir del juego deportivo: Un modelo de enseñanza para la comprensión (Learning to manage conflicts in physical education classes from the sports tactical game: A teaching model for u. Retos, 42, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva-Bartoll, O., & Fernández-Rio, J. (2021). Advocating for service-learning as a pedagogical model in physical education: Towards an activist and transformative approach. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 27, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva-Bartoll, O., Maravé-Vivas, M., Salvador-García, C., & Valverde-Esteve, T. (2021a). Impact of a phys-ical education service-learning programmer on ASD children: A mixed-methods ap-proach. Children and Youth Services Review, 126(2), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva-Bartoll, O., Moliner, L., & Salvador-García, C. (2020a). Can service-learning promote social well-being in primary education students? A mixed method approach. Children and Youth Services Review, 111, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva-Bartoll, O., Montero, P. J. R., Capella-Peris, C., & Salvador-García, C. (2020b). Effects of service learning on physical education teacher education students’ subjective happiness, prosocial behavior, and professional learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 517601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiva-Bartoll, O., Ruiz-Montero, P. J., Leiva-Olivencia, J. J., & Grönlund, H. (2021b). The effects of service-learning on physical education teacher education: A case study on the border between Africa and Europe. European Physical Education Review, 27(4), 1014–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, G. R. (2025). Aprendizaje Servicio: Su implicación transformadora en el ámbito de la educación física. Revista Neuronum, 11(2), 13–29. Available online: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-0016-9901 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Cuji-Bunsi, L. C., Pino-Loza, E. D., & Granja-Pino, A. C. (2024). Aprendizaje servicio y creación de liderazgo para una cultura de paz. Revista Científica Y Arbitrada De Ciencias Sociales Y Trabajo Social, 7(13), 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeley, S. (Ed.). (2015). Academic writing in service-learning. In Critical perspectives on service-learning in higher education (pp. 103–139). Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Cruz, J. M. (2021). La conducta prosocial en niños y niñas de escuelas primarias. Voces de la Educación, 6(11), 3–32. Available online: https://www.revista.vocesdelaeducacion.com.mx/index.php/voces/issue/view/39 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- European Commission. (2018). Council recommendation (EU) 2018/C 189/01 of 22 May 2018 on key competences for lifelong learning. Official Journal of the European Union C, 189, 1–13. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018H0604(01) (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research (5th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- García-Rico, L., Santos-Pastor, M. L., Martínez-Muñoz, L. F., & Ruiz-Montero, P. J. (2021). The building up of professional aptitudes through university service-learning’s methodology in sciences of physical activity and sports. Teaching and Teacher Education, 105, 103402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaviria-Cortés, D., Arboleda-Serna, V., Guerra-Escudero, J., Chaverra-Fernández, B., Bustamante-Castaño, S., Arango-Paternina, C., González-Palacio, E., Muriel-Echavarría, J., & Ramírez-Martínez, L. (2023). Motivation and likes of high school students towards physical education class. European Journal of Human Movement, 51, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J., Cayuela, D., & López, C. (2019). Prosocialidad, educación física e inteligencia emocional en la escuela. Journal of Sport & Health Research, 11(1), 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- González-Valencia, C., García-Miranda, M., & Troncoso-Ulloa, K. (2025). Aprendizaje autónomo y portafolio: Percepciones de docentes en formación en pedagogía en Educación Física. Retos: Nuevas Perspectivas de Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Spain. (2020). Organic law 3/2020, of 29 December, which amends organic law 2/2006, of 3 May, on education (LOE). Boletín Oficial del Estado, 340, 122868–122953. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2020/12/29/3 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Government of Spain. Ministry of Education and Vocational Training. (2022). Royal decree 157/2022, of 1 March, establishing the organisation and minimum teaching requirements for primary education. Boletín Oficial del Estado. 52 (2 de marzo de 2022). Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2022-3296 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Hassan, H., Mohammed, S., Mohammed, A., & Ghanem, S. (2024). Study nurses’ knowledge about fall prevention among elderly women. Journal of Orthopaedic Science and Research, 5(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooli, E.-M., Corral-Robles, S., Ortega-Martín, J. L., Baena-Extremera, A., & Ruiz-Montero, P. J. (2023). The Impact of Service Learning on Academic, Professional and Physical Wellbeing Competences of EFL Teacher Education Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20, 4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javier-Ríos, J. E. (2025). Habilidades comunicativas en estudiantes de educación básica: Una revisión sistemática. Revista InveCom, 5(3), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. L., Adkins, D., & Chauvin, S. (2020). A review of the quality indicators of rigor in qualitative research. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 84(1), 7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S. R., & Abes, E. S. (2020). The nature and impact of service-learning on college students. Journal of College Student Development, 61(2), 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2017). Experiential learning theory as a guide for experiential educators in higher education. ELTHE: A Journal for Engaged Educators, 1(1), 7–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, P. (2004). Managing for the common good: Prosocial leadership. Organizational Dynamics, 33(3), 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucero-Sarmiento, M. G., & Jarrín-Navas, S. A. (2021). Percepción de la educación física como asignatura entre los actores del entorno escolar. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Humanidades, Educación, Ciencia y Tecnología, 7(3), 650–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinek, T., & Hellison, D. (2016). Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility: Past, Present and Future. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 87(5), 9–13. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/teaching-personal-social-responsibility-past/docview/1795623201/se-2 (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Meyers, S. A. (2009). Service learning as an opportunity for personal and social transformation. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 21(3), 373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, K. M. (2025). Autorregulación emocional e interacción social en situaciones motrices en Educación Física en la etapa de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. In M. J. Cardoso-Moreno, & F. Anaya-Benítez (Eds.), Nuevas perspectivas y retos en la sociedad actual. Acercando el concepto GRIT a la sociedad (pp. 1–15). Dykinson. [Google Scholar]

- Mora, Á. R. (2020). Estereotipos negativos hacia la vejez y su relación con variables sociodemográficas en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios. Revista INFAD de Psicología. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1), 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, D. C. (2022). Propuestas de aprendizaje servicio en educación física para facilitar la transición de primaria a secundaria. EmásF: Revista Digital de Educación Física, 13(74), 116–133. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro-Patón, R., Lago-Ballesteros, J., & Basanta-Camiño, S. (2019a). Prosocial behaviors of primary education schoolchildren: The influence of cooperative games. SPORT TK-EuroAmerican Journal of Sport Sciences, 8(2), 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Patón, R., Lago-Ballesteros, J., & Basanta-Camiño, S. (2019b). Relation between motivation and enjoyment in physical education classes in children from 10 to 12 years old. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 14(3), 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R., Thomsen, B. S., & Berry, A. (2022). Learning through playat school—A framework for policyand practice. Frontiers in Education, 7, 751801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Ordás, R., Nuviala, A., Grao-Cruces, A., & Fernández-Martínez, A. (2021). Implementing service-learning programs in physical education; Teacher education as teaching and learning models for all the agents involved: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resch, K., & Schrittesser, I. (2023). Using the service-learning approach to bridge the gap between theory and practice in teacher education. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 27(10), 1118–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Montero, E., Sánchez-Trigo, H., Batista, P., & Ruiz Montero, P. J. (2024). Participación en un experiencia aprendizaje-servicio intergeneracional y conductas prosociales: La importancia de la educación física y su rol mediador. Revista Iberoamericana de Ciencias de La Actividad Física y El Deporte, 13(2), 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Montero, P. J., Chiva-Bartoll, O., Salvador-García, C., & González-García, C. (2020). Learning with Older Adults through Intergenerational Service Learning in Physical Education Teacher Education. Sustainability, 12(3), 1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Montero, P. J., Corral-Robles, S., García-Carmona, M., & Leiva-Olivencia, J. J. (2023). Development of prosocial competencies in PETE and Sport Science students. Social justice, Service-Learning and Physical Activity in cultural diversity contexts. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 28(3), 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvador-García, C., Garcés, X. F., Ribeiro-Silva, E., & Chiva-Bartoll, O. (2022). Aprendizaje-Servicio Universitario en Educación Física: Una interpretación no-lineal de sus complejidades. Opción, 38(99), 41–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Pastor, M., Chiva-Bartoll, O., Martínez-Muñoz, L. F., & Ruiz-Montero, P. J. (2021). Contributions of service-learning to more inclusive and less gender-biased physical education: The views of Spanish physical education teacher education students. Journal of Gender Studies, 30(6), 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Pastor, M., Puerta, I. G., de Miguel, J. F., & Cubero, H. A. (2025). Matriz de Indicadores para el Diseño y Evaluación de Buenas Prácticas de Aprendizaje-Servicio Universitario. REICE: Revista Iberoamericana sobre Calidad, Eficacia y Cambio en Educación, 23(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos Pastor, M. L., Martínez Muñoz, L. F., Cuenca Soto, N., Chiva Bartoll, O., & Ruiz-Montero, P. J. (2024). Evaluación formativa y compartida en Educación Física: Fundamentos y aplicaciones. Editorial Académica. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez-Gallego, N. M., Abellán, J., & Segovia, Y. (2025). Oportunidades de inclusión social para personas con discapacidad intelectual mediante un programa de Aprendizaje-servicio. Sportis. Scientific Journal of School Sport, Physical Education and Psychomotricity, 11(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C., Díaz, M. J. S., & Gonzalez-Villora, S. (2025). El aprendizaje-servicio en edad escolar en el área de educación física: Una revisión sistemática. Retos, 64, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M. C., Ferreira, S., & Gomes, R. (2017). Investigación social. Teoría, método y creatividad. Lugar Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Todres, L., Galvin, K. T., & Holloway, I. (2009). The humanization of healthcare: A value framework for qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 4(2), 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, J. R., Álvarez, J. J., & Obando, E. S. (2025). La inteligencia emocional en la educación física de primaria y secundaria: Una revisión sistemática. Retos: Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 62, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vives, M., Orte, C., Amer, J., & Quesada, V. (2021). Evaluación del cambio en los participantes del programa intergeneracional de educación primaria compartir la infancia. Revista Iberoamericana de Evaluación Educativa, 14(2), 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zueck Enríquez, M. del C., Ramírez García, A. A., Rodríguez Villalobos, J. M., & Irigoyen Gutiérrez, H. E. (2020). Satisfacción en las clases de Educación Física y la intencionalidad de ser activo en niños del nivel de primaria (Satisfaction in the physical education classroom and intention to be physically active in primary school children). Retos, 37, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-Montero, E.E.; Sanchez-Trigo, H.; Mohamed-Mohamed, K.; Ruiz-Montero, P.J. Developing Prosocial Leadership in Primary School Students: Service-Learning and Older Adults in Physical Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070845

Ruiz-Montero EE, Sanchez-Trigo H, Mohamed-Mohamed K, Ruiz-Montero PJ. Developing Prosocial Leadership in Primary School Students: Service-Learning and Older Adults in Physical Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):845. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070845

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-Montero, Encarnación E., Horacio Sanchez-Trigo, Kamal Mohamed-Mohamed, and Pedro Jesús Ruiz-Montero. 2025. "Developing Prosocial Leadership in Primary School Students: Service-Learning and Older Adults in Physical Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070845

APA StyleRuiz-Montero, E. E., Sanchez-Trigo, H., Mohamed-Mohamed, K., & Ruiz-Montero, P. J. (2025). Developing Prosocial Leadership in Primary School Students: Service-Learning and Older Adults in Physical Education. Education Sciences, 15(7), 845. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070845