Abstract

Middle school students face significant transitions and often do not receive education on important social-emotional learning (SEL) skills. To address this issue, we investigated how middle school students experience an outdoor adventure education program focused on SEL development. Nine students from an urban public charter school participated in the ROVER program, which taught the following SEL skills: resilience, risk management, self-efficacy, self-regulation, and emotion regulation. Students then applied these concepts through adventure sports and were instructed to translate the lessons to their home and school lives. Students completed weekly reflections to explore how students experienced this piloted program. A Structure Tabular-Thematic Analysis (ST-TA) approach was used to investigate thematic coding of reflections. Prominent themes uncovered across the reflections were emotion regulation, experience intensity, social influences, resilience, and self-preservation. We describe program implementation and discuss how using adventure sports after-school programs can impact urban middle school students’ SEL skills development. Implications suggest potential benefits of directly teaching and applying SEL competencies.

1. Urban Middle Schoolers’ Experiences of an Outdoor Adventure Education Program to Facilitate Social Emotional Learning

Middle school adolescents must learn to deal with myriads of developmental tasks, including navigating new academic environments, forming peer/social groups, undergoing physical changes, and an ever-shifting self-concept (Eccles et al., 1993; Eccles & Roeser, 2012). How they approach these challenges has a direct impact on school motivation, their sense of self-worth, self-esteem, emotional control, and social skills (Akos et al., 2015; Brass et al., 2019; Coelho et al., 2017; Rogers et al., 2017). Failure to properly navigate these challenges can lead to mental health difficulties, which have a negative influence on academic achievement, motivation, and social development (Auger, 2011; Kelly, 2013; Vander Stoep et al., 2003). Therefore, educators should aim to design programs that support students through these challenges. However, teachers must often prioritize academic content during the school day, which leaves little time for social-emotional learning (SEL) skill development that would be particularly beneficial for students during this transitional period (Buchanan et al., 2009; Morgan et al., 2022). Thus, afterschool programs aimed at addressing student SEL skills, including motivation, resilience, and mental health, are an effective and needed mechanism for promoting well-being (Sjogren et al., 2023). Lowe Vandell and Lao (2016) highlighted the beneficial outcomes of after-school programming on student academic and socio-emotional outcomes. Of particular importance, researchers emphasize the positive impact afterschool programs have on facilitating a perceived safe environment where children are able to foster positive relationships and develop social skills through engaging in collaborative activities (Brown et al., 2022; Christian et al., 2019, 2021b; Gustafsson et al., 2012; Hwang et al., 2022; White et al., 2022). Within the context of this environment, students are provided with opportunities to engage in real-life experiences, thereby enhancing their understanding and application of learning such as cooperation, empathy, and self-regulation, all which are critical components of SEL (Harun & Salamuddin, 2014; Sibthorp et al., 2015).

To further understand participant experiences, we designed and piloted an afterschool program focused on teaching SEL skills to a group of racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse urban middle school students. The diversity of participants in outdoor education programs also plays a crucial role in shaping SEL outcomes. This outdoor adventure education (OAE) program taught students about SEL skills, encouraged them to apply the skills to adventure sports (e.g., whitewater rafting), and then promoted transfer of the ideas to everyday home and school life. In doing so, we investigated how and whether the intervention fostered participants’ application of SEL skills to the adventure sports and their out-of-program experience. In their study, Germinaro et al. (2021) found participants’ social-emotional growth experiences varied across different cultural backgrounds in an outdoor education context, indicating the need for culturally sustaining pedagogies in these programs. This highlights the importance of inclusivity in outdoor education, ensuring that all students can benefit from the social-emotional learning opportunities provided. This study furthered our understanding of the types of experiences participants have in the program and led to programmatic modifications in future iterations.

2. Literature Review

Afterschool programs have been shown to support student academic engagement and achievement, such as increased focus, attendance, and prosocial adaptive behaviors (Beightol et al., 2012; Bowers et al., 2019; Brown et al., 2022; Kremer et al., 2015; Richmond et al., 2017). Further, students of lower socioeconomic status are less likely to participate in outdoor activities or spend time in the natural environment compared to their peers from higher socioeconomic households (Richmond & Sibthorp, 2019). Researchers identify that this lack of access and participation results in lower physical activity, school engagement, sense of belonging, interpersonal skills, and resiliency (Overholt & Ewert, 2015; Peacock et al., 2021; Richmond & Sibthorp, 2019). Therefore, a comprehensive, student-centered afterschool program focused on SEL skills can lead to a variety of beneficial outcomes for schools and communities, including improved school climate and safety, increased achievement, reduced exclusionary discipline, and improved youth engagement by focusing on students’ social, emotional, and behavioral wellbeing (Christian et al., 2019; Rafa et al., 2021). OAE is an evidence-based strategy that school workers may employ to promote students’ mental health and enhance educational outcomes (Ewert, 2014; Fletcher & Hinkle, 2002), which involves learning various topics while engaging in adventure sports (e.g., kayaking, whitewater rafting, etc.). We elaborate on the promise of OAE programs for promoting SEL skills and academic outcomes next.

2.1. Outdoor Adventure Education

To address motivation and mental-emotional wellness as a preventative and responsive intervention, OAE programs have demonstrated effectiveness with a diversity of people in a variety of contexts (Gass et al., 2012; McIver et al., 2018; Swank & Daire, 2010). OAE is an evidenced-based approach that school professionals can use to foster social-emotional development in students and improve education outcomes. In OAE, students engage in various adventure sports activities (e.g., kayaking, rowing, mountain biking) and then think about how they experienced SEL constructs (e.g., resilience, self-efficacy) during those activities. Doing so allows students to experience SEL in real-time. Moreover, the opportunity to personally experience these processes and reflect on them in real time should foster SEL within and beyond the OAE context (Lazowski & Hulleman, 2016). OAE facilitators work with students to think about how they experienced activities and SEL constructs (recreational processing), how they can recognize and build upon their strengths during these experiences (educational processing), and how they can apply SEL skills to their educational experiences in school (transformational processing).

OAE intentionally uses the natural environment and kinesthetic activities to engage students through a parallel process that attends to students’ cognitive, behavioral, affective, and physical dimensions. Participation in kinesthetic activities is associated with improved well-being through increased psychological and social competence, self-efficacy, academic performance, sense of peer support and friendships, and development of initiative and self-determination (Powrie et al., 2015). Facilitators of OAE programs consist of educators and mental-health professionals who follow the integrated OAE process model to engage participants in an exploratory process to bring about recreational, educational, and transformational change (Christian et al., 2021a). Being aware of and growing one’s motivation and coping mechanisms is essential for positive development (Denham & Brown, 2010). An admirable objective for teachers is to provide opportunities to practice and develop their abilities in this area. However, due to pressures and priorities, most in-class time is spent on academic material, leaving little time for social and emotional growth (Bouffard, 2021; McClelland et al., 2017). Therefore, after-school activities offer a chance to concentrate explicitly on these essential skills (Bowers et al., 2019; Durlak et al., 2010; Faircloth & Bobilya, 2021). In fact, in a literature review, Hurd and Deutsch (2017) found that after-school programs in particular were effective for facilitating SEL skills. Taken together, OAE is thus a practical strategy for promoting motivation and coping strategies.

While OAE research has been shown to have positive effects on resilience (Beightol et al., 2012; Kelly, 2013; Scarf et al., 2017), group climate (Christian et al., 2019), and well-being (Luttenberger et al., 2015; Ritchie et al., 2014; Tracey et al., 2018), a review of the literature yielded limited results examining the effects of OAE programs centered around specific experiential activities in collaboration between educators, mental health professionals, community partners, and schools. Therefore, in the current study, we uniquely contributed to the literature by (a) drawing from both the OAE literature and (b) demonstrating the potential of OAE for fostering SEL outcomes.

2.2. Social-Emotional Learning Skills

In addition to academic skills, schools have started to consider methods for addressing social, emotional, and behavioral competencies (Greenberg, 2023; Kim et al., 2024). SEL is operationalized as the process of learning social and emotional skills including self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making (Greenberg, 2023; Kim et al., 2024). SEL skills are broadly defined and can include characteristics related to motivation, behavior regulation, and management of emotions (Guo et al., 2023; Kim et al., 2024). Development of SEL skills has been shown to have a positive impact on a myriad of beneficial outcomes including improved competence, improved student behavior, drops in discipline referrals, student engagement in the classroom, and increases in student achievement (Alzahrani et al., 2019; Atkins et al., 2023; Durlak et al., 2011, 2022; Greenberg, 2023; Guo et al., 2023; Min et al., 2024; Murano et al., 2020). Therefore, teaching SEL skills to students is an important goal for educators. Yet despite the empirical evidence showing the benefit of teaching SEL skills in school, insufficient time and training often create challenges for educators to integrate SEL skills with academic content during class (Buchanan et al., 2009; Christian & Brown, 2018; Humphries et al., 2018).

Current SEL frameworks may not attend to the various experiences and values of students from lower socioeconomic (SES) backgrounds (Jagers et al., 2019). Research demonstrates that effective SEL programs require adaptations tailored to specific populations, such as students from lower SES backgrounds (Jagers et al., 2019; Li et al., 2025). Students from lower SES backgrounds may value SEL skills but often do not apply them in situations they perceive as unsafe or uncontrollable, such as bullying or harassment (van de Sande et al., 2024). SEL interventions must move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach and intentionally integrate relevant, context specific changes that are grounded in authentic community experiences and values to be effective (Li et al., 2025; van de Sande et al., 2024). Additional involvement and training of teachers to address the unique social and environmental challenges with students of lower SES backgrounds will ensure meaningful social and emotional development for youth (Jagers et al., 2019; Li et al., 2025; van de Sande et al., 2024).

To help alleviate these challenges, we taught SEL skills to students in an afterschool program and encouraged them to apply those ideas to their education to improve academic outcomes. More specifically, our program taught students about SEL skills and how to use scientific principles to strengthen them, provides students with experiences to apply those strategies and skills during adventure activities, and opportunities to apply those strategies to their out-of-program life. Below, we outline and define the variables we included in our instruction on SEL skills.

SEL Skills Explored and Fostered in the Current Study

Self-efficacy refers to a person’s competence beliefs for a particular task (Bandura, 1986). It captures the degree to which a person is confident that they can perform the necessary actions that are precursors to success in that specific task. There is ample evidence that self-efficacy influences effort, persistence, and the quality of engagement in academic work (e.g., Cech et al., 2011; Chen & Tutwiler, 2017; Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2012; Shell & Husman, 2008; Usher et al., 2019). Recognizing and influencing one’s own self-efficacy is an important skill for students.

Resilience is defined as positive adaptation and the ability to persist through adverse experiences (Herrman et al., 2011). Resilience has been shown to have a positive influence on student motivation, engagement, and achievement in school (Goleman, 1995; Luthar et al., 2006; Min et al., 2024). Therefore, fostering student resilience can be important to facilitate success in school, especially given obstacles and challenges that may arise. We take a strengths-based approach to our research and thus recognize the environmental, social, and historical factors that influence students (Rashid, 2015). That is, we believe that all students have resilience, and our goal is to design a learning environment that supports students to build on and recognize their resilience in context (Bozic et al., 2018). Recognizing one’s resilience and its components can empower students to assert their existing resilience in a beneficial manner. One aspect of resilience taught in our program is risk management, or supporting students in recognizing different types of risks and acting accordingly (Herrman et al., 2011).

Self-regulation occurs when students exert agency over their goal-directed behavior (Schunk & Zimmerman, 2007; Sibthorp et al., 2015). That is, students engage in the processes of self-observation, self-judgment, and self-reaction (Bandura, 1986; Kanfer & Gaelick-Buys, 1991; Karoly & Kanfer, 1982). Students who self-regulate make a plan of action to achieve a goal, observe their strategies, evaluate their progress toward their goals, and modify their strategies if necessary (Greene et al., 2021; Kuhlmann et al., 2023). When students more effectively engage in self-regulation strategies, they are more likely to experience high quality motivation, engagement, and achievement (Dent & Koenka, 2016; Eilam & Reiter, 2014; Richardson et al., 2012; Schraw et al., 2006). Therefore, teaching students about self-regulation can have a positive benefit on their school engagement and academic outcomes.

Emotion regulation is a specific type of self-regulation that reflects the process of using strategies to shift current emotions to more desired emotions (Tamir et al., 2020). More specifically, emotion regulation involves the process of responding to, managing, and modifying emotional responses to achieve goals or meet environmental demands (Thompson, 1994). The ability to regulate emotions predicts a decrease in psychological stress (Aldao et al., 2010), an increase in well-being (Gruber et al., 2013; Kashdan & Rottenberg, 2010; Quoidbach et al., 2015), and contributes to academic outcomes (Ivcevic & Brackett, 2015). Therefore, we aimed to teach students about the components of emotion regulation.

Taken together, in the current study, we focused on how students experienced the following SEL outcomes: self-efficacy, resilience, self-regulation, and emotion regulation. Given literature documenting the positive impact of OAE programs on these processes (e.g., Beightol et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2023; Christian et al., 2021b; Cordle et al., 2016; Deane et al., 2017; Overholt & Ewert, 2015; Molyneux et al., 2022; Peacock et al., 2021; Richmond & Sibthorp, 2019; Ritchie et al., 2014; Sibthorp et al., 2015) we expected that our OAE program would promote these outcomes.

2.3. Purpose

The purpose of the current study was to increase student accessibility to outdoor adventure education activities and understand students’ experiences of the program informing their development of SEL skills. Moreover, we aimed to iteratively improve the ROVER program as we continue to scale up our research and serve more students more effectively. Based on our aims, goals, and understanding of the literature, the following question guided our research: How do middle school students describe their experience of an OAE program on the development of their SEL skills?

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

Upon receiving Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, students were recruited by the school principal to participate in the program using flyers developed by the researchers. A total of nine 8th grade students from one urban city charter school in the South-Central region of the United States participated in the ROVER pilot program. Over 35% of the school was considered economically disadvantaged. Student demographic data indicated six students identified as male and three as female; four students identified as Black/African American, two as Latino/a, and three as white. Informed consent, assent, and liability waiver forms were completed by participants and their guardians.

3.2. Self-Reflection Instruments

We used a journaling method called Notice Change Value (NCV) journals, which are an impactful method for facilitating experiential learning experiences (Heddy et al., 2021, 2023; Heddy & Sinatra, 2013, 2017). NCV journals include students writing about where they Noticed ideas in a new context (motivated use), how it Changed their experience (expansion of perception), and why the idea is Valuable to them (experiential value). We implemented NCV journals before an adventure sport (pre-reflection), after an adventure sport (post-reflection), and in their out-of-program experience (take-home activity). Grounded in literature discussed in earlier sections, we expected that engagement in transformative experience with SEL constructs through the OAE would encourage learning and application of those ideas.

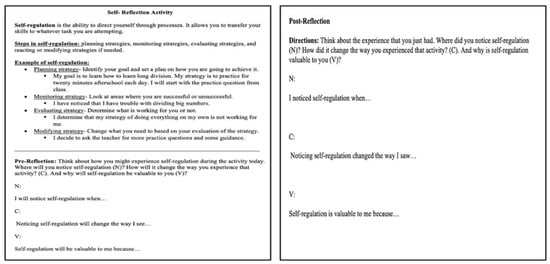

NCV Journal Pre-Reflection Activity. Students received the pre-reflection activity (see Figure 1) each week before participating in the adventure sport. In the pre-reflection activity, the SEL skill of the week is described to teach students about the SEL skill. That is, students were asked to report where they think they will Notice the SEL skill during the activity (e.g., self-efficacy during surfing), how the SEL skill will Change the way they experience the activity (e.g., will think about how self-efficacy goes up or down when succeeding or failing during surfing), and in what ways they will Value the SEL skill (e.g., made them more likely to try surfing again even after falling). The goal of the pre-reflection activity was to encourage students to begin thinking about where they may experience SEL skills during the adventure sports. That is, the more that students practice pre-contemplation or briefing of the concept, the more they will be likely to experience it. After completing the pre-reflection activity, students engaged in the sport.

Figure 1.

Pre- and Post-Reflection Activities.

NCV Journal Post-Reflection Activity. After engaging in the adventure sport, students returned to educational programming and completed the post-reflection activity (see Figure 1) This activity asked students to think about where they experienced the SEL skill during the activity. Again, we utilized the NCV framework and asked students to report where they noticed the SEL skill during the activity, how the SEL skill changed their experience, and why the SEL skill was valuable to them. We provided a worked example on the document to help the students when generating their own examples. Students turned in their post-reflection activity and were given their take-home activity. The goal of the post-reflection activity was to teach the SEL skill through application, give students practice engaging in the experience, and further promote application to their school experience.

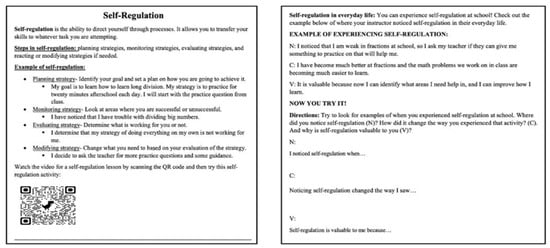

NCV Journal Take-Home Activity. The take-home activity asked students to engage in the NCV process a second time (see Figure 2). In contrast to the pre- and post-reflection activities, however, the take-home activity asked students to report where they noticed the SEL skill outside of the program, how the SEL skill changed an experience at home or in school, and why the SEL skill is valuable in their everyday lives. The activity sheet included a description of the SEL skill, a worked example of where the student might experience the SEL skill at school, and a QR code that linked to a YouTube video that teaches the student about the SEL skill. Given that these SEL skills can be challenging to learn, we did not expect students to remember all aspects of them. Thus, reteaching is a useful practice (Heddy et al., 2023). Students had a week to complete the take-home activity before submitting at the next week’s session.

Figure 2.

Take-Home Activity.

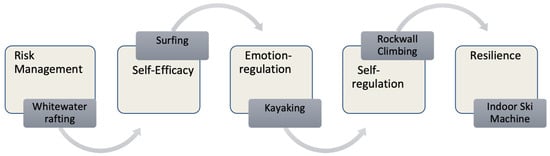

3.3. Program Procedures

The ROVER program was co-created by two of the researchers, an adventure sport non-profit, and school administration partners and was facilitated by the researchers and adventure sport community partner employees. The program met weekly for 90 min for five weeks to engage in various outdoor adventure activities. The order of activities was selected based on seasonal factors such as temperature and available sport guides. For example, water activities were conducted first because the temperature cooled by the end of the 5-week session. White water rafting was conducted first because rafting guides were only available early in the season. Each week, participants would learn about an SEL concept perceived to be associated with the specific weekly kinesthetic activity prior to engaging in the activity in order to apply the SEL skill, followed by processing their experience of applying the SEL skills and how those skills would transfer to everyday life. Next, they engaged in the pre-NCV activity and then completed the outdoor adventure activity. Each activity was intentionally selected to accompany a specific SEL skill. For instance, the first week consisted of students learning about risk management before engaging in white water rafting. Students were taught about real versus perceived risk and how to mitigate risk in context of the activity. Students then engaged in the activity under the supervision of a whitewater rafting guide. Following the activity, students completed an NCV activity to reflect on how they experienced and applied their risk management skills during the activity, their perceived value of risk management, and how risk management applied to other areas of their daily life outside the context of the whitewater rafting activity. Finally, participants completed the above-mentioned survey to assess self-efficacy, resilience, and TE. Participant data was administered, collected, and analyzed by the researchers’ graduate research assistants. Figure 3 illustrates a timeline of activity and associated SEL concepts.

Figure 3.

Order of Activities and Topics.

4. Analysis

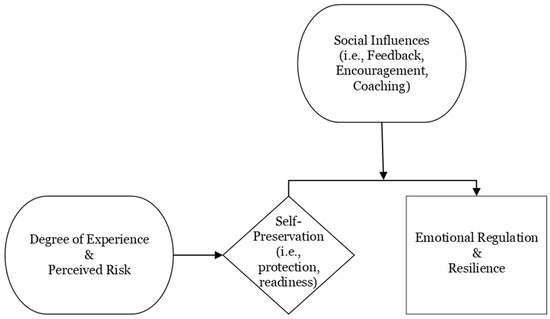

Structured Tabular-Thematic Analysis. We followed the guidelines for Structure Tabular-Thematic Analysis (ST-TA) outlined by Robinson (2022), which provides a comprehensive guide to the qualitative analysis of brief texts. The first and second author coded participant responses independently to develop initial themes. Once initial independent themes were identified, the two authors met to discuss and revise the codes. Using the revised codes, each author recoded participant statements. Upon completion of recoding, authors met to check agreement and discuss disagreements. This process results in identified sematic themes, explicit, surface-level meanings of the data; and latent themes, more nuanced, underlying, implicit meanings and assumptions to uncover deeper patterns and interpretations with the data (Robinson, 2022). Once authors reached a consensus, theme frequencies were explored (see Table 1). The final step was to produce a thematic map illustrating the relationship and influences of themes as illustrated in Figure 4.

Table 1.

Thematic Frequency.

Figure 4.

Thematic Map.

5. Results

- RQ: How do students describe their experience of SEL skills as a part of the OAE program?

Participant responses yielded five latent themes: emotional regulation, degree of prior experience, social influence, resilience, and self-preservation. Each theme is accompanied by semantic themes discussed within each latent theme. A thematic map is provided to illustrate the relationship between themes (see Figure 4).

Emotion Regulation. Emotion regulation emerged as latent theme described by participants who reported semantic themes of experiencing panic/anxiety, fear, enjoyment, and fun. In one such instance, students reported feeling scared on their initial ascent to go whitewater rafting and noted anxiety around falling out of the boat. Once they went down the rapids successfully, they reported a sense of fun and diminished fear and anxiety. Additionally, participant enjoyment of the activity was informed by the natural environment (i.e., weather, water, clothing/protection). Indicating that how participants prepared for and perceived the environment informed their engagement and experience of the activity. For instance, one participant reported noticing resiliency when, “I climbed up and back down, but the second time I jumped off, watching other people jumping off changed the way I saw resiliency which is valuable to me because it can help to overcome your fears”. Another participant stated, “I didn’t feel afraid going the second time”. Further, participants transferred their experiences to daily life with statements like “On the first day of piano I sucked it made me frustrated and mad; I put my anger to the side and put my best effort into the piano”. They also reflected on the importance of emotional regulation: “Emotions are valuable because you can express them at any time and make you [conscious] of what’s happening”.; “I feel a change in emotion when we hit the water. It gave me a sense of pride and enjoyment which made my experience better”.

Degree of Prior Experience. Degree of prior experience, as a latent theme, was unique to participants. Some participants were attempting activities for the first time, whereas others had prior experience with the activity or a similar one. Degree of prior experience appeared to inform participants’ reported confidence levels before and during each activity, a semantic theme. Several participants with lower prior experience indicated their confidence was informed by their ability to attempt novel activities, practicing and re-attempting the activity, and successfully completing their aspiration or objective for the activity. One participant stated, “I did the boogie boarding and surfing twice. Because the second time [I noticed self-efficacy because] I knew what I was doing”. Participants with prior experience indicated confidence was informed by their previous experience of engaging in the activity, having practiced the activity, and successfully completing the activity. One participant reported noticing a change in his confidence during the ‘leap of faith’ element of the rock-climbing activity: “the first time I was nervous, but now I am not as nervous, [learning about resiliency] is valuable to me because it helps me do things when I don’t want to”. One participant recalled past similar experiences to support their engagement in the activity: “I’ve used a penny board before and gone at great speeds so I feel confident”.

Social Influences. Participants reported many experiences that reflected social influence, including receiving feedback, persuasion, being coached, and feeling encouraged by group members and also engaging in the activities. For example, participant motivation and confidence were informed by the perceived sense of support from others (i.e., coached, observed, vocal encouragement), feeling challenged, and overcoming the challenge of fear and/or physical difficulty associated with the activity. As of note, the group climate fostered engagement and encouragement, which did not always result in success. For instance, when attempting a challenge such as the rock-climbing wall, participants found it difficult to reach the top for various reasons (i.e., skill level, height, equipment). However, participants offered support to each other and focused on the present goal of attempting the next move as opposed to reaching the top, likely because of their own experience. Doing so provided them with the opportunity to work together and develop strategies for re-attempting their challenge. For instance, one participant stated, “I noticed resiliency when I was struggling to climb, noticing resiliency changed the way I saw my friend coached me, which is valuable because it helps me complete the task”. A couple participants specifically highlighted their peers’ influence: “My peers pumped me up,” and “people called out that I could do it… I also took harder rout[es]”.

Resilience (Approach to Challenge/Persistence). Participant resilience (i.e., get back up, recover, bounce back) was informed by their ability to listen to instructions, make a plan, and observe obstacles. During the snow skiing activity, one participant stated, “I started skiing a bit [far] back so I planned on getting back front so I positioned myself to go forward,” which reflects their ability to identify an extrinsic challenge and make the necessary adjustment to achieve their goal. Another participant noted a connection to physical traits related to ability and how they are actively responding: “I noticed my stamina is weak so I practice stamina training”. During kayaking, a participant highlighted, “it got too hard and my [arms] almost fell off”, but having to persist through the physical challenge to return back to the dock. Participants then associated the concepts to daily life, such as “I notice I am bad at jumping things on my bike, I can get better at it with practice”.

Self-Preservation. Self-preservation is operationalized as participants’ sense of agency and preparedness to act in protecting their physical and emotional health; gravitate towards a sense of safety to maintain personal well-being. Participant self-preservation was informed by the perceived risk associated with the activity and how perceived risk-informed their affect. One participant shared, “[I noticed my] anxiety from the chance of falling in”. However, the associated risk also informed their enjoyment of the activity. For example, participants reflected on their experience with white water rafting: “It [risk] made it fun after the first ride”. Another participant highlighted the value of assessing risk because, “It shows me to be ready even if you don’t know what’s gonna happen”. Self-preservation was evident in participants’ transference to life outside of the activities, such as, “When I walk my dog there are a lot of dangers like cars and homeless [people] so [I’]m careful like looking both ways and not talking to strangers”.

Based upon the thematic results and participant quotes, the themes appear to be dynamically related. For instance, participants’ degree of experience and perceived risk associated with the activity appeared to inform their sense of self-preservation. This sense of self-preservation influenced participants’ emotional regulation and sense of resilience. Interestingly, social influence appeared to be a mediator of emotional regulation and sense of resilience. For instance, when participants with a lower degree of experience or higher sense of perceived risk with the activity became stuck, peer relationships and coaching appeared to be an impetus for supporting participants’ ability to emotionally regulate or persist through a challenge or obstacle, whether intrinsic or extrinsic, to obtain a goal.

6. Discussion

Our main goal for this research was to design the program and gain preliminary insights into how participants engage with the activities and concepts in and out of the program. More specifically, we investigated how participants applied SEL constructs including resilience, risk management, self-efficacy, self-regulation, and emotion-regulation, while engaging in adventure sports and during their everyday lives. We begin this section by summarizing the findings. Next, we interpret the findings within the context of broader literature. We then conclude our discussion with some theoretical and practical implications that emerge from our work.

6.1. Summary of Results

In this preliminary analysis of our pilot program aimed at teaching SEL skills to urban middle school students, we provided a qualitative thematic analysis related to students’ reflections on the program. The thematic analysis generated 5 unique themes emergent in the data: emotion regulation, prior experience, social influence, resilience, and self-preservation.

Interpretation of Findings

The frequency of themes generated from students’ responses was informative for exhibiting the extent to which participants experienced the program and SEL constructs within and across time points. Results suggested that some activity-construct pairs may be more conducive to effective SEL learning than others. Based on the analysis of five outdoor activities (white-water rafting, surfing, rock climbing, kayaking, and indoor skiing), several key patterns emerged in how participants experienced and processed these challenging activities.

Self-preservation emerged as the dominant theme across all activities, with 37 total mentions. This theme was particularly pronounced during high-risk activities like white-water rafting and technical activities like indoor skiing. Participants consistently demonstrated awareness of safety measures, preparation needs, and protective strategies. During white-water rafting, this manifested through explicit focus on life vests and safety procedures, while during indoor skiing, it appeared more in terms of technical ability, attention to instruction and preparation, and physical control.

Emotional regulation formed the second most prominent theme with 34 mentions, peaking notably during the kayaking activity. This suggests that participants were highly attuned to their emotional states and actively working to manage them. The kayaking activity appeared to elicit a particularly wide range of emotions, from anxiety about falling in to pride in accomplishment, especially when pushing through physical challenges like exhaustion or physical muscle fatigue that affected their emotional state and mindset, requiring emotional management.

Resilience was present throughout the activities with 30 mentions, but was mostly evident during rock climbing. The vertical challenge of climbing seemed to create natural opportunities for participants to experience and overcome obstacles, with many references to “pushing through,” “getting back up,” and “trying again”. This resilience was often supported by social encouragement, highlighting an interesting intersection between themes.

The degree of experience, mentioned 26 times, appeared to play a crucial role in participants’ confidence and performance, particularly during surfing. Participants frequently referenced how previous experience or growing familiarity with an activity influenced their approach and confidence levels. This was especially evident in activities that allowed for multiple attempts, where participants could track their improvement over time.

Social influences, with 23 mentions, emerged as a crucial supporting element across activities but were prominent during rock climbing. The presence of peers, guides, and instructors provided not just practical support but emotional encouragement that often aided participants in pushing through challenges. This social dimension appeared to be particularly important during activities that required visible individual performance, like rock climbing, where peer encouragement could directly impact participant success.

These themes didn’t operate in isolation but showed an interesting pattern of interaction. For example, strong social support often enhanced resilience, while greater experience typically led to better emotional regulation. Self-preservation concerns tended to decrease as experience increased, suggesting that familiarity with activities helped participants better balance safety with challenge. The progression through different activities revealed how participants developed various psychological tools and strategies for managing challenging situations. Each activity appeared to emphasize different combinations of these themes, contributing to a comprehensive learning experience that built participants’ capacity for managing both physical and emotional challenges.

This idea that participants’ degree of experience and perceived risk associated with the activity appeared to inform sense of self-preservation is supported by research showing that both personal experience and risk perception interact to shape individuals’ self-protective behaviors, with more experienced individuals in high-risk activities often perceiving less risk and engaging in more calculated self-preservation strategies (Raue et al., 2018). Raue and colleagues (2018) found that participants with greater experience were associated with lower perceived risk and increased reliance on skill development and preparation to manage uncertainty and maintain control in the context of indoor climbing.

Further, the notion that self-preservation influences participants’ emotional regulation and sense of resilience underscores self-regulation as a key protective factor for resilience. Mestre et al. (2017) reported that the ability to regulate emotions is a significant predictor of resilience, and that cognitive strategies such as positive reappraisal can further enhance perceived resilience. Therefore, effective emotional regulation strategies predict higher resilience, especially in challenging or adverse contexts.

Interestingly, social support or peer influence appeared to be a strong mediator of emotional regulation and sense of resilience. For instance, when participants with a lower degree of experience or higher sense of perceived risk became stuck, peer relationships and coaching appeared to be an impetus for supporting participants’ ability to emotionally regulate or persist through a challenge or obstacle, whether intrinsic or extrinsic, and achieve their goal. This is consistent with evidence that perceived social support and peer interactions can mediate the relationship between resilience and emotional regulation, with peer support and coaching enhancing individuals’ capacity to manage stress, regulate emotions, and persist in the face of difficulty (Sahi et al., 2023; Surzykiewicz et al., 2022). Their studies found that social support not only improves emotional regulation in the moment but also builds resilience for future challenges, highlighting the critical role of social relationships in fostering adaptive coping and persistence.

The findings support social learning theory (Bandura, 1986), particularly regarding the role of peer influence and collective efficacy. Throughout the activities, social support emerged as a crucial facilitator of both skill development and emotional regulation. This suggests that adventure programming may provide uniquely effective contexts for social learning, where peer support becomes intrinsically linked to both safety and success. Consistent with these themes, literature suggests mastery experiences to be one of the strongest predictors of self-efficacy (Chen & Tutwiler, 2017; Usher & Pajares, 2008). Additional factors that influence self-efficacy are vicarious experience (e.g., observing a peer experiencing success), social persuasion, and emotion (Bandura, 1986). Each of these factors may have had a positive impact on participants’ resiliency. In particular, participants watched their peers have successful experiences across the range of activities. Participants may have received feedback and social persuasion from peers and instructors, which may have influenced their self-efficacy (Usher et al., 2019). Finally, participants may have felt nervous at first, which may have initially reduced their self-efficacy (Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., 2012). However, as they practiced, their anxiety may have decreased and positive emotions such as excitement and enjoyment may have replaced nervousness, leading to a corresponding positive impact on self-efficacy. Taken together and consistent with the literature, participants may have experienced mastery, vicarious experiences, social persuasion, and/or emotions that promoted their self-efficacy as they progressed through the ROVER program.

6.2. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The emergence of participants’ self-preservation illuminates an interesting finding from this study because historically, programs predominantly attend to post-program outcomes such as affect, autonomy, self-efficacy, resilience, empathy, and pro-social skills (Beightol et al., 2012; Brown et al., 2023; Christian et al., 2021b; Coelho et al., 2017; Cordle et al., 2016; Deane et al., 2017; Faircloth & Bobilya, 2021). Interestingly, the literature appears to miss attending to participant processes that influence these outcomes such as degree of experience, perceived sense of safety and risk, and sense of self-preservation. Perhaps a shift in perspective toward including participant factors related to fear is required to yield a complete understanding of the potential of OAE programs. Therefore, the field would benefit from future research exploring the influences of these participant characteristics and inputs that may inform participant outcomes. Numerous researchers highlight group dynamics and opportunities for growth as influential factors that contribute to positive changes but often cite challenges or difficulties among participants are less observable (Bowers et al., 2019; Christian et al., 2019). Bowers et al. (2019) indicate that participants noted activities involving heights (e.g., high rope courses) or environmental factors (e.g., weather, dirt, mud) often contributed negatively to participant’s experiences. While the findings of external environmental factors were similar to our study, it is important to better understand the internal experience or factors within our locus of control. For instance, research can illuminate participants that have higher degrees of self-preservation, and lower degrees of experience may not result in increased positive or adaptive outcomes such as pro-social skills and resilience.

The progressive nature of challenge across different activities, combined with the consistent presence of support mechanisms, suggests resilience might be optimally developed through carefully structured exposure to challenge rather than through either protection or overwhelming difficulty. This supports and refines current theories about resilience development while suggesting new pathways for investigation. This is informative to practitioners and educators developing these programs as they are encouraged to assess the unique needs of each participant and attend or respond to these needs and to encourage participation or adaptation of the program or activity (AEE, n.d.; Christian et al., 2019; Fletcher & Hinkle, 2002; Schoel & Maizell, 2002). For instance, practitioners may need to adjust an activity based on a participant’s degree of experience and how they choose to partner participants to engage in a rock-climbing activity. To help inform a participant’s sense of safety and risk, the practitioner may choose to spend additional time providing instruction of the equipment and safety measures in place and give participants a more detailed walkthrough of the activity during the briefing of the activity, such as white-water rafting. Taken together, the results suggest that self-preservation should be taken into consideration when designing OAE programs aimed at influenced SEL skills.

Practically speaking, findings from participant experiences inform program design and implementation. OAE programs that are intentionally structured to provide progressive challenges while maintaining adequate support systems. When participants can experience challenge within a framework that promotes peer support and individual agency, data suggests optimal learning occurs. So, reconceptualizing risk management practices for both physical and psychological safety, which may include stakeholders receiving psychological first aid and skills related to understanding and addressing emotional responses and behaviors. The strong presence of self-preservation behaviors suggests participants actively engage in risk assessment, indicating programs might benefit from explicitly teaching risk evaluation skills rather than simply imposing rules. Further, encouraging peer learning and play to inform skill development and emotional regulation, suggesting instructional design should intentionally create opportunities for positive peer interaction and support. Playmeo.com (Collard, n.d.) is one particular resource that educators and facilitators could reference for encouraging connection, social interaction, and team building.

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions

We aimed to accomplish three goals in the current study: (1) provide students with access to otherwise inaccessible adventure activities, (2) achieve educational objectives focused on SEL development through these activities, and (3) document participant experiences to guide future programs. As this was a pilot program, we identified several limitations and areas for improvement.

While the sample size and composition of nine 8th-grade students from a single school is might be considered a limitation for generalizability due to some homogeneity, the reported themes and documentation appeared to reach saturation. However, our participant demographics represent a meaningful contribution to educational psychology research, which has historically focused on white, middle-class students (DeCuir-Gunby & Schutz, 2014; Usher, 2018). Our study included strong representation from racially/ethnically minoritized students and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Future research should build on this foundation by recruiting larger, more diverse samples while maintaining focus on minoritized students.

Another concern is inconsistent attendance poses challenges, with only one session (time 2) achieving full participation. We observed multiple factors, including school commitments, family obligations, and health issues, affected participant attendance. These fluctuations in group composition likely influenced group dynamics and further restricted our already limited dataset. While our small group size aligns with experiential education best practices which recommend 6–12 participants to ensure quality instruction and processing (AEE, n.d.), future iterations would benefit from multiple concurrent groups and more diverse age/grade representation.

Several opportunities exist to enhance program efficacy. The complex themes that emerged suggest traditional skill-based assessments may not capture important developmental outcomes, indicating the need for more comprehensive evaluation methods. Therefore, our future improvements could include resequencing activities and topics to optimize educational reinforcement, incorporating teacher and parent observations to assess impact beyond the program setting and reduce participant response bias, and training local practitioners to facilitate the program independently and thereby reducing researcher bias.

7. Conclusions

Our pilot study aimed to implement and evaluate an outdoor adventure education (OAE) program designed to teach social-emotional learning (SEL) skills to a group of urban middle school students. Qualitative themes highlighted how factors like emotional regulation, prior experience levels, social influences, resilience mindset, and self-preservation impacted students’ engagement and meaning making. This pilot study offers valuable insights to refine the ROVER curriculum and implementation. Matching SEL skills to complementary adventure activities, adjusting for varying student experience levels, and addressing self-preservation concerns may enhance transformative experience and positive youth development outcomes. Future research should explore these participant factors through more robust longitudinal and mixed methods designs with larger, more diverse samples. Ultimately, findings emphasize the potential of intentionally designed OAE programs to provide urban youth with empowering experiences that build critical social-emotional competencies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L.B. and B.C.H.; methodology, C.L.B. and B.C.H.; software, C.L.B. and B.C.H.; validation, C.L.B., B.C.H., K.S.G. and J.G.; formal analysis, C.L.B., B.C.H., K.S.G. and J.G.; investigation, C.L.B., B.C.H., K.S.G. and J.G.; resources, C.L.B., B.C.H., K.S.G. and J.G.; data curation, C.L.B., B.C.H., K.S.G. and J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.B., B.C.H., K.S.G. and J.G.; writing—review and editing, C.L.B., B.C.H. and A.C.K.; visualization, C.L.B.; supervision, C.L.B., B.C.H. and A.C.K.; project administration, B.C.H.; funding acquisition, B.C.H. and C.L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Jeannine Rainbolt College of Education, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Oklahoma (protocol code 15021; approved 15 September 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- AEE. (n.d.). Adventure therapy best practices. Available online: https://assets.noviams.com/novi-file-uploads/aee/TAPG_Adventure_Therapy_Best_Practices__1_.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Akos, P., Rose, R., & Orthner, D. (2015). Sociodemographic moderators of middle school transition effects on academic achievement. Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(2), 170–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M., Alharbi, M., & Alodwani, A. (2019). The effect of social-emotional competence on children academic achievement and behavioral development. International Education Studies, 12(12), 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, J. L., Vega-Uriostegui, T., Norwood, D., & Adamuti-Trache, M. (2023). Social and emotional learning and ninth-grade students’ academic achievement. Journal of Intelligence, 11(9), 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, R. W. (2011). The school counselor’s mental health sourcebook: Strategies to help students succeed. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 4(3), 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beightol, J., Jevertson, J., Carter, S., Gray, S., & Gass, M. (2012). Adventure education and resilience enhancement. Journal of Experiential Education, 35(2), 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouffard, S. (2021). To make SEL stick, align school and out-of-school time. The Learning Professional, 42(4), 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, E. P., Larson, L. R., & Sandoval, A. M. (2019). Urban youth perspectives on the benefits and challenges of outdoor adventure camp. Journal of Youth Development, 14(4), 122–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozic, N., Lawthom, R., & Murray, J. (2018). Exploring the context of strengths—A new approach to strength-based assessment. Educational Psychology in Practice, 34(1), 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brass, N., McKellar, S., North, E., & Ryan, A. (2019). Early adolescents’ adjustment at school: A fresh look at grade and gender differences. Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(5), 689–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. L., Christian, D. D., & Crowson, H. M. (2023). Effects of an adventure therapy mountain bike program on middle school students’ resiliency. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 9(2), 222–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. L., Smarinsky, E. C., McCarty, D. L., & Christian, D. D. (2022). Student experiences of an adventure therapy mountain bike program during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning, 22(4), 313–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, R., Gueldner, B. A., Tran, O. K., & Merrell, K. W. (2009). Social and emotional learning in classrooms: A survey of teachers’ knowledge, perceptions, and practices. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 25(2), 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, E. A., Rubineau, B., Silbey, S., & Seron, C. (2011). Professional role confidence and gendered persistence in engineering. American Sociological Review, 76, 641–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. A., & Tutwiler, M. S. (2017). Implicit theories of ability and self-efficacy. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 225(2), 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, D. D., & Brown, C. L. (2018). Recommendations for the role and responsibilities of school-based mental health counselors. Journal of School-Based Counseling Policy and Evaluation, 1(1), 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, D. D., Brown, C. L., & Portrie-Bethke, T. L. (2019). Group climate and development in adventure therapy: An exploratory study. Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 44(1), 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, D. D., McCarty, D. L., & Brown, C. L. (2021a). Navigating adventure therapy: Using adlerian theory as a guide. Journal of Individual Psychology, 77(3), 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, D. D., McMillion, P., Brown, C. L., Schoonover, T. J., & Miller, B. A. (2021b). Using adventure therapy to improve self-efficacy of middle school students. Journal of School Counseling, 19(26), n26. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, V. A., Marchante, M., & Jimerson, S. R. (2017). Promoting a positive middle school transition: A randomized-controlled treatment study examining self-concept and self-esteem. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, M. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.playmeo.com/ (accessed on 23 August 2022).

- Cordle, J., Van Puymbroeck, M., Hawkins, B., & Baldwin, E. (2016). The effects of utilizing high element ropes courses as a treatment intervention on self-efficacy. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 50(1), 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, K. L., Harré, N., Moore, J., & Courtney, M. G. R. (2017). The impact of the project k youth development program on self-efficacy: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(3), 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeCuir-Gunby, J. T., & Schutz, P. A. (2014). Researching race within educational psychology contexts. Educational Psychologist, 49(4), 244–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denham, S. A., & Brown, C. (2010). “Plays nice with others”: Social–emotional learning and academic success. Early Education and Development, 21(5), 652–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, A. L., & Koenka, A. C. (2016). The relation between self-regulated learning and academic achievement across childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 28, 425–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A., Mahoney, J. L., & Boyle, A. E. (2022). What we know, and what we need to find out about universal, school-based social and emotional learning programs for children and adolescents: A review of meta-analyses and directions for future research. Psychological Bulletin, 148(11–12), 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2012). School influences on human development. In L. C. Mayes, & M. Lewis (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of environment in human development (pp. 259–283). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., Midgley, C., Reuman, D., Iver, D. M., & Feldlaufer, H. (1993). Negative effects of traditional middle schools on students’ motivation. The Elementary School Journal, 93(5), 553–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilam, B., & Reiter, S. (2014). Long-term self-regulation of biology learning using standard junior high school science curriculum. Science Education, 98(4), 705–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewert, A. W. (2014). Outdoor adventure education: Foundations, theory, and research. Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Faircloth, W. B., & Bobilya, A. J. (2021, November 1–3). Impact of a community-based outdoor and adventure programming on participant social and emotional learning. 2021 Symposium on Experiential Education Research, Virtual (online). [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher, T. B., & Hinkle, J. S. (2002). Adventure based counseling: An innovation in counseling. Journal of Counseling and Development, 80(3), 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gass, M. A., Gillis, H. L., & Russell, K. C. (2012). Adventure therapy: Theory, research, and practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Germinaro, K., Dunn, E., Polk, K. D., de Vries, H. G., Daugherty, D., & Jones, J. (2021). Diversity in outdoor education: Discrepancies in SEL across a school overnight program. Journal of Experiential Education, 45(3), 256–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. (1995). EQ: Why it can matter more than IQ. Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, M. T. (2023). Evidence for social and emotional learning in schools. Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greene, J. A., Plumley, R. D., Urban, C. J., Bernacki, M. L., Gates, K. M., Hogan, K. A., Demetriou, C., & Panter, A. T. (2021). Modeling temporal self-regulatory processing in a higher education biology course. Learning and Instruction, 72, 101201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, J., Kogan, A., Quoidbach, J., & Mauss, I. B. (2013). Happiness is best kept stable: Positive emotion variability is associated with poorer psychological health. Emotion, 13(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J., Tang, X., Marsh, H. W., Parker, P., Basarkod, G., Sahdra, B., Ranta, M., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2023). The roles of social-emotional skills in students’ academic and life success: A multi-informant and multicohort perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(5), 1079–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, P. E., Szczepanski, A., Nelson, N., & Gustafsson, P. A. (2012). Effects of an outdoor education intervention on the mental health of schoolchildren. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 12(1), 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun, M. T., & Salamuddin, N. (2014). Promoting social skills through outdoor education and assessing its’ effects. Asian Social Science, 10(5), 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heddy, B. C., Danielson, R. W., Ross, K., & Goldman, J. A. (2023). Everyday engineering: The effects of transformative experience in middle school engineering. Journal of Engineering Education, 112(3), 674–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heddy, B. C., Nelson, K. G., Husman, J., Cheng, K. C., Goldman, J. A., & Chancey, J. B. (2021). The relationship between perceived instrumentality, interest and transformative experiences in online engineering. Educational Psychology, 41(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heddy, B. C., & Sinatra, G. M. (2013). Transforming misconceptions: Using transformative experience to promote positive affect and conceptual change in students learning about biological evolution. Science Education, 97(5), 723–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heddy, B. C., & Sinatra, G. M. (2017). Transformative parents: Facilitating transformative experiences and interest with a parent involvement intervention. Science Education, 101(5), 765–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrman, H., Stewart, D. E., Diaz-Granados, N., Berger, E. L., Jackson, B., & Yuen, T. (2011). What is resilience? The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 56(5), 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphries, M. L., Williams, B. V., & May, T. (2018). Early childhood teachers’ perspectives on social-emotional competence and learning in urban classrooms. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 34(2), 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, N., & Deutsch, N. (2017). SEL-focused after-school programs. The Future of Children, 27(1), 95–115. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44219023 (accessed on 17 March 2023). [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S. H. J., Cappella, E., Kieffer, M. J., & Yates, M. (2022). “Let’s hang out!”: Understanding social ties among linguistically diverse youth in urban afterschool programs. Social Development, 31(1), 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivcevic, Z., & Brackett, M. A. (2015). Predicting creativity: Interactive effects of openness to experience and emotion regulation ability. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 9(4), 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., & Williams, B. (2019). Transformative social and emotional learning (SEL): Toward SEL in service of educational equity and excellence. Educational Psychologist, 54(3), 162–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanfer, F. H., & Gaelick-Buys, L. (1991). Self-management methods. In F. H. Kanfer, & A. P. Goldstein (Eds.), Helping people change (3rd ed.). Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Karoly, P., & Kanfer, F. H. (1982). Self-management and behavior change: From theory to practice. Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, T. B., & Rottenberg, J. (2010). Psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J. (2013). House subcommittee examines current mental health services in schools. The chronicle of social change. Available online: https://chronicleofsocialchange.org/featured/capitol-view-on-kids-the-latest-from-washington-on-children-and-families-3/2311 (accessed on 23 November 2023).

- Kim, E. K., Allen, J. P., & Jimerson, S. R. (2024). Supporting student social emotional learning and development. School Psychology Review, 53(3), 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, K. P., Maynard, B. R., Polanin, J. R., Vaughn, M. G., & Sarteschi, C. M. (2015). Effects of after-school programs with at-risk youth on attendance and externalizing behaviors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 616–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhlmann, S. L., Bernacki, M. L., & Greene, J. A. (2023). A multimedia learning theory-informed perspective on self-regulated learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 174, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazowski, R. A., & Hulleman, C. S. (2016). Motivation interventions in education: A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 602–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A., Miller, F. G., & Williams, S. C. (2025). Cultural adaptations to social–emotional learning programs: A systematic review. School Psychology, 40(2), 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenbrink-Garcia, L., Pugh, K. J., Koskey, K. L., & Stewart, V. C. (2012). Developing conceptual understanding of natural selection: The role of interest, efficacy, and basic prior knowledge. The Journal of Experimental Education, 80(1), 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe Vandell, D., & Lao, J. (2016). Building and retaining high quality professional staff for extended education programs. International Journal for Research on Extended Education, 4(1), 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthar, S. S., Sawyer, J. A., & Brown, P. J. (2006). Conceptual issues in studies of resilience: Past, present, and future research. In B. M. Lester, A. S. Masten, & B. McEwen (Eds.), Resilience in children (pp. 105–115). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Luttenberger, K., Stelzer, E. M., Först, S., Schopper, M., Kornhuber, J., & Book, S. (2015). Indoor rock climbing (bouldering) as a new treatment for depression: Study design of a waitlist-controlled randomized group pilot study and the first results. BMC Psychiatry, 15, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClelland, M. M., Tominey, S. L., Schmitt, S. A., & Duncan, R. (2017). SEL interventions in early childhood. Future of Children, 27(1), 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIver, S., Senior, E., & Francis, Z. (2018). Healing fears, conquering challenges: Narrative outcomes from a wilderness therapy program. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 13(4), 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestre, J. M., Núñez-Lozano, J. M., Gómez-Molinero, R., Zayas, A., & Guil, R. (2017). Emotion regulation ability and resilience in a sample of adolescents from a suburban area. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H. J., Park, S.-H., Lee, S.-H., Lee, B.-H., Kang, M., Kwon, M. J., Chang, M. J., Negi, L. T., Samphel, T., & Won, S. (2024). Building resilience and social–emotional competencies in elementary school students through a short-term intervention program based on the SEE learning curriculum. Behavioral Sciences, 14(6), 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molyneux, T. M., Zeni, M., & Oberle, E. (2022). Choose Your own adventure: Promoting social and emotional development through outdoor learning. Early Childhood Education Journal, 51, 1525–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, L., Close, S., Siller, M., Kushner, E., & Brasher, S. (2022). Teachers’ experiences: Social emotional engagement–knowledge and skills. Educational Research, 64(1), 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murano, D., Sawyer, J. E., & Lipnevich, A. A. (2020). A meta-analytic review of preschool social and emotional learning interventions. Review of Educational Research, 90(2), 227–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overholt, J. R., & Ewert, A. (2015). Gender matters: Exploring the process of developing resilience through outdoor adventure. The Journal of Experiential Education, 38(1), 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, J., Bowling, A., Finn, K., & McInnis, K. (2021). Use of outdoor education to increase physical activity and science learning among low-income children from urban cchools. American Journal of Health Education, 52(2), 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powrie, B., Kolehmainen, N., Turpin, M., Ziviani, J., & Copley, J. (2015). The meaning of leisure for children and young people with physical disabilities: A systematic evidence synthesis. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 57(11), 993–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoidbach, J., Mikolajczak, M., & Gross, J. J. (2015). Positive interventions: An emotion regulation perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 141(3), 655–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafa, A., McCann, M., Francies, C., & Evans, A. (2021). State funding for student mental health. Policy Brief. Education Commission of the States. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, T. (2015). Positive psychotherapy: A strength-based approach. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(1), 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raue, M., Kolodziej, R., Lermer, E., & Streicher, B. (2018). Risks seem low while climbing high: Shift in risk perception and error rates in the course of indoor climbing activities. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richmond, D., & Sibthorp, J. (2019). Bridging the opportunity gap: College access programs and outdoor adventure education. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership, 11(4), 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, D., Sibthorp, J., Gookin, J., Annarella, S., & Ferri, S. (2017). Complementing classroom learning through outdoor adventure education: Out-of-school-time experiences that make a difference. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 18(1), 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, S. D., Wabano, M. J., Russell, K., Enosse, L., & Young, N. L. (2014). Promoting resilience and wellbeing through an outdoor intervention designed for Aboriginal adolescents. Rural Remote Health, 14(1), 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, O. C. (2022). Conducting thematic analysis on brief texts: The structured tabular approach. Qualitative Psychology, 9(2), 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, A. A., DeLay, D., & Martin, C. L. (2017). Traditional masculinity during the middle school transition: Associations with depressive symptoms and academic engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46(4), 709–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahi, R. S., Eisenberger, N. I., & Silvers, J. A. (2023). Peer facilitation of emotion regulation in adolescence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 62, 101262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarf, D., Hayhurst, J., Riordan, B., Boyes, M., Ruffman, T., & Hunter, J. (2017). Increasing resilience in adolescents: The importance of social connectedness in adventure education programmes. Australasian Psychiatry, 25(2), 154–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoel, J., & Maizell, R. (2002). Exploring islands of healing: New perspectives on adventure-based counseling. Project Adventure. [Google Scholar]

- Schraw, G., Crippen, K. J., & Hartley, K. (2006). Promoting self-regulation in science education: Metacognition as part of a broader perspective on learning. Research in Science Education, 36, 111–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2007). Influencing children’s self-efficacy and self-regulation of reading and writing through modeling. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 23(1), 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shell, D. F., & Husman, J. (2008). Control, motivation, affect, and strategic self-regulation in the college classroom: A multidimensional phenomenon. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibthorp, J., Collins, R., Rathunde, K., Paisley, K., Schumann, S., Pohja, M., Gookin, J., & Baynes, S. (2015). Fostering experiential self-regulation through outdoor adventure education. Journal of Experiential Education, 38(1), 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjogren, A. L., Robinson, K. A., & Koenka, A. C. (2023). Profiles of afterschool motivations: A situated expectancy-value approach. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 74, 102197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surzykiewicz, J., Skalski, S. B., Sołbut, A., Rutkowski, S., & Konaszewski, K. (2022). Resilience and regulation of emotions in adolescents: Serial mediation analysis through self-esteem and the perceived social support. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), 8007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swank, J. M., & Daire, A. P. (2010). Multiple family adventure-based therapy groups: An innovative integration of two approaches. The Family Journal, 18(3), 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamir, M., Vishkin, A., & Gutentag, T. (2020). Emotion regulation is motivated. Emotion, 20(1), 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R. A. (1994). Emotion regulation: A theme in search of definition. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2), 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, D., Gray, T., Truong, S., & Ward, K. (2018). Combining acceptance and commitment therapy with adventure therapy to promote psychological wellbeing for children at-risk. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, E. L. (2018). Acknowledging the whiteness of motivation research: Seeking cultural relevance. Educational Psychologist, 53(2), 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, E. L., Li, C. R., Butz, A. R., & Rojas, J. P. (2019). Perseverant grit and self-efcacy: Are both essential for children’s academic success? Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(5), 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, E. L., & Pajares, F. (2008). Sources of self-efficacy in school: Critical review of the literature and future directions. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 751–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Stoep, A., Weiss, N. S., Kuo, E. S., Cheney, D., & Cohen, P. (2003). What proportion of failure to complete secondary school in the US population is attributable to adolescent psychiatric disorder? The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 30(1), 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Sande, M. C. E., Fekkes, M., Diekstra, R. F. W., Gravesteijn, C., Kocken, P. L., & Reis, R. (2024). Low-achieving adolescent students’ perspectives on their interactions with classmates. An exploratory study to inform the implementation of a social emotional learning program in prevocational education. Children and Youth Services Review, 156, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A. M., Akiva, T., Colvin, S., & Li, J. (2022). Integrating social and emotional learning: Creating space for afterschool educator expertise. AERA Open, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).