Key Research Questions to Support Neurodiversity in Higher Education: A Participatory Priority Setting Exercise

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

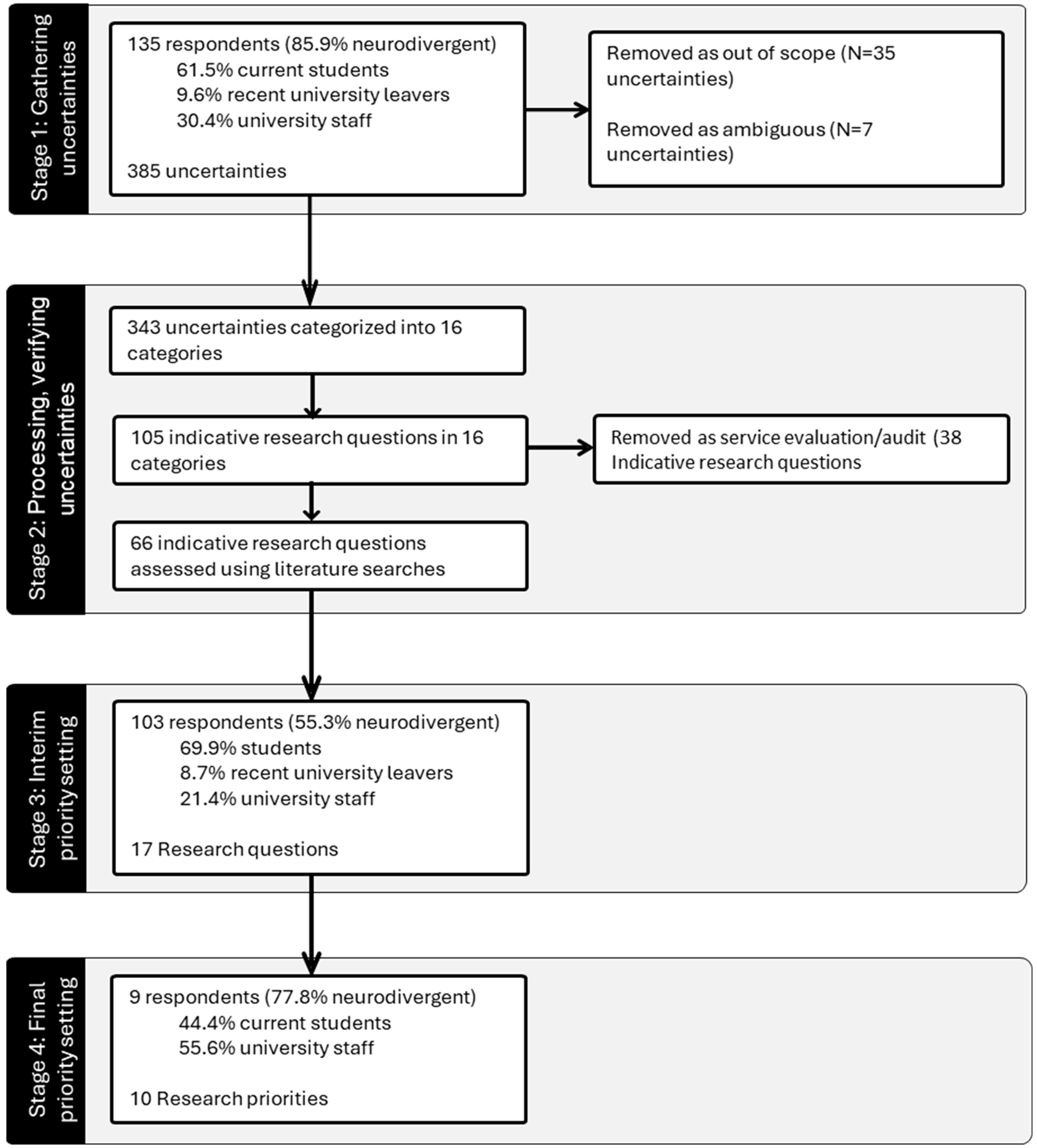

2.1. Stage 1: Gathering Uncertainties

2.2. Stage 2: Data Processing and Verifying Uncertainties

2.3. Stage 3: Interim Priority Setting

2.4. Stage 4: Final Priority Setting

3. Results

3.1. Stage 1 Findings: Initial Uncertainties

3.2. Stage 2 Findings: Categorising and Verifying Uncertainties

3.2.1. Accessing Support

3.2.2. Alcohol, Substance Use, Self-Medication

3.2.3. Assessment

3.2.4. Diagnosis, Learning Performance and Success

3.2.5. Disclosure Experiences and Impact

3.2.6. Mental Health and Wellbeing

3.2.7. Neurodivergent Staff

3.2.8. Student Experience: Beyond Studies

3.2.9. Support

3.2.10. University Community

3.3. Stage 3 Findings: Interim Priority Setting Results

3.4. Stage 4 Findings: Final Priority Settings

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, R. (2025). Quarter of leading UK universities cutting staff due to budget shortfalls. The Guardian. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, T. (2010). Neurodiversity: Discovering the extraordinary gifts of autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other brain differences. ReadHowYouWant.com. [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach, R. P., Mortier, P., Bruffaerts, R., Alonso, J., Benjet, C., Cuijpers, P., Demyttenaere, K., Ebert, D. D., Green, J. G., Hasking, P., Murray, E., Nock, M. K., Pinder-Amaker, S., Sampson, N. A., Stein, D. J., Vilagut, G., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2018). WHO world mental health surveys international college student project: Prevalence and distribution of mental disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127(7), 623–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottini, S. B., Morton, H. E., Buchanan, K. A., & Gould, K. (2023). Moving from disorder to difference: A systematic review of recent language use in autism research. Autism in Adulthood, 6(2), 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, T., Claire, P., Mahbub, S., Joy, W., Charlotte, R., & Clemans, A. (2023). Priority setting in higher education research using a mixed methods approach. Higher Education Research & Development, 42(4), 816–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouder, L., Karakus, M., Cinotti, A., Ferreyra, M. V., Fierros, G. A., & Rojo, P. (2020). Neurodiversity in higher education: A narrative synthesis. Higher Education, 80(4), 757–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M. T., Watts, G. W., & López, E. J. (2021). A systematic review of firsthand experiences and supports for students with autism spectrum disorder in higher education. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 84, 101769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, M., & Samarawickrema, G. (2010). The criteria of effective teaching in a changing higher education context. Higher Education Research & Development, 29(2), 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C., & Sherman, H. (2006). Teaching effectiveness and student achievement: Examining the relationship. Educational Research Quarterly, 29(4), 40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson Waters, S., & Torgerson, C. J. (2021). Dyslexia in higher education: A systematic review of interventions used to promote learning. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(2), 226–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerksen, K., Besney, R., Ames, M., & McMorris, C. A. (2021). Supporting autistic adults in postsecondary settings: A systematic review of peer mentorship programs. Autism Adulthood, 3(1), 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrant, F., Owen, E., Hunkins-Beckford, F. L., & Jacksa, M. (2022). Celebrating neurodiversity in higher education. Psychologist, 35, 2–3. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J., Margaret, B., David, B., & Tai, J. (2024). How does assessment drive learning? A focus on students’ development of evaluative judgement. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 49(2), 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, C. T., & Fabiano, G. A. (2019). The transition of youth with ADHD into the workforce: Review and future directions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 22(3), 316–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gyimah, S. (2018). Universities must ensure their mental health services are fit. Department for Education. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, A. G., Pollock, B., & Holmes, A. (2022). Provision of extended assessment time in post-secondary settings: A review of the literature and proposed guidelines for practice. Psychological Injury and Law, 15(3), 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, B., Gupta, J., Bilics, A., & Taff, S. D. (2018). Balancing efficacy and effectiveness with philosophy, history, and theory-building in occupational therapy education research. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 6(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntley, Z., & Young, S. (2014). Alcohol and substance use history among ADHD adults: The relationship with persistent and remitting symptoms, personality, employment, and history of service use. Journal of Attention Disorders, 18(1), 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgens, A. (2020). Neurodiversity in a neurotypical world: An enactive framework for investigating autism and social institutions. In Neurodiversity studies (pp. 73–88). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Karalyte, C. (2024). Studying at university with different types of neurodiversity. Available online: https://www.studentbeans.com/blog/uk/studying-at-university-with-different-types-of-neurodiversity/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Kovshoff, H., Vrijens, M., Thompson, M., Yardley, L., Hodgkins, P., Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S., & Danckaerts, M. (2013). What influences clinicians’ decisions about ADHD medication? Initial data from the influences on prescribing for ADHD questionnaire (IPAQ). European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 22(9), 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenney, E. E., Brunwasser, S. M., Richards, J. K., Day, T. C., Kofner, B., McDonald, R. G., Williams, Z. J., Gillespie-Lynch, K., Kang, E., Lerner, M. D., & Gotham, K. O. (2023). Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic prospective predictor of depression and anxiety symptoms in neurodiverse first-semester college students. Autism in Adulthood, 5(4), 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, S. S., King, M., & Tully, M. P. (2016). How to use the nominal group and Delphi techniques. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 38(3), 655–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellifont, D. (2023). Ableist ivory towers: A narrative review informing about the lived experiences of neurodivergent staff in contemporary higher education. Disability & Society, 38(5), 865–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, D., Stafinski, T., & Martin, D. (2007). Priority-setting for healthcare: Who, how, and is it fair? Health Policy, 84(2), 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurlin, R. T., & Senko, C. (2025). Whom are you trying to impress? Pursuing performance goals for parents, teachers, or classmates. Journal of Educational Psychology, 117(4), 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriña, A., & Biagiotti, G. (2022). Academic success factors in university students with disabilities: A systematic review. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 37(5), 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Research. (2021). JLA guidebook. Available online: https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/jla-guidebook (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Nelson, H., Switalsky, D., Ciesielski, J., Brown, H. M., Ryan, J., Stothers, M., Coombs, E., Crerear, A., Devlin, C., Bendevis, C., Ksiazek, T., Dwyer, P., Hack, C., Connolly, T., Nicholas, D. B., & DiRezze, B. (2023). A scoping review of supports on college and university campuses for autistic post-secondary students. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1179865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieminen, J. H., & Yang, L. (2024). Assessment as a matter of being and becoming: Theorising student formation in assessment. Studies in Higher Education, 49(6), 1028–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, C., Maryanne, B., Sadhbh, O. S., Christina, S., & Nearchou, F. (2022). How does diagnostic labelling affect social responses to people with mental illness? A systematic review of experimental studies using vignette-based designs. Journal of Mental Health, 31(1), 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohlmeier, M. D., Peters, K., Te Wildt, B. T., Zedler, M., Ziegenbein, M., Wiese, B., Emrich, H. M., & Schneider, U. (2008). Comorbidity of alcohol and substance dependence with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Alcohol Alcohol, 43(3), 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otu, M. S., & Sefotho, M. M. (2024). Examination of emotional distress, depression, and anxiety in neurodiverse students: A cross-sectional study. World Journal of Psychiatry, 14(11), 1681–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollak, D. (2009). Neurodiversity in higher education: Positive responses to specific learning differences. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, S. J. (2023). Rowan university full-time instructors’ knowledge and attitudes regarding neurodiversity and neurodivergent undergraduate students [Master’s thesis, Rowan University]. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/rowan-university-full-time-instructors-knowledge/docview/2802764336/se-2?accountid=11862 (accessed on 9 May 2025).

- Sampson, K., Priestley, M., Dodd, A. L., Broglia, E., Wykes, T., Robotham, D., Tyrrell, K., Ortega Vega, M., & Byrom, N. C. (2022). Key questions: Research priorities for student mental health. BJPsych Open, 8(3), e90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick, J. A., Merwood, A., & Asherson, P. (2019). The positive aspects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A qualitative investigation of successful adults with ADHD. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, 11(3), 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedgwick-Müller, J. A., Müller-Sedgwick, U., Adamou, M., Catani, M., Champ, R., Gudjónsson, G., Hank, D., Pitts, M., Young, S., & Asherson, P. (2022). University students with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A consensus statement from the UK Adult ADHD Network (UKAAN). BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S. C. K., & Anderson, J. L. (2018). The experiences of medical students with dyslexia: An interpretive phenomenological study. Dyslexia, 24(3), 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, J. (1999). Why can’t you be normal for once in your life? From a ‘problem with no name’ to the emergence of a new category of difference. In M. Corker, & S. French (Eds.), Disability discourse (pp. 59–67). Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, M. D., & Lindo, E. J. (2023). Executive functioning supports for college students with an autism spectrum disorder. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 10(4), 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, A. E., Abu-Ramadan, T. M., & Hartung, C. M. (2022). Promoting academic success in college students with ADHD and LD: A systematic literature review to identify intervention targets. Journal of American College Health, 70(8), 2342–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson-Hodgetts, S., Labonte, C., Mazumder, R., & Phelan, S. (2020). Helpful or harmful? A scoping review of perceptions and outcomes of autism diagnostic disclosure to others. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 77, 101598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vignoles, A., & Murray, N. (2016). Widening participation in higher education. Education Sciences, 6(2), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widman, C. J., & Lopez-Reyna, N. A. (2020). Supports for postsecondary students with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50(9), 3166–3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintre, M. G., & Yaffe, M. (2000). First-year students’ adjustment to university life as a function of relationships with parents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 15(1), 9–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Category Description | Initial Uncertainties | Indicative Questions | Indicative Research Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accessing Support | These relate to accessing support for neurodivergent students rather than the experience or effectiveness of it, for example, who can access it and what steps are involved in doing so. | 27 | 10 | 1 |

| Alcohol, Substance Use, (Self-) Medication | These relate to use of substances in neurodivergent students (excluding medication used as prescribed) and the proportion who receive prescribed medication. | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Assessment | These relate to the suitability of different forms of assessment neurodivergent students and the value of adjustments to assessment. | 39 | 7 | 6 |

| Campus Spaces | These relate to the suitability of physical and digital spaces within universities for neurodivergent individuals. | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| Careers support | These relate to support for employability of neurodivergent students, including during placements (i.e., as part of their degree) and through university career services. | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Degree and University Choices | These relate to how neurodivergent students perceive subjects when selecting degrees and what factors impact neurodivergent choices about degree subjects and universities. | 12 | 4 | 2 |

| Diagnosis, Learning Performance and Success | These relate to how neurodivergent students compare to neurotypical students in terms of degree outcomes, dropout rates, and time taken to complete qualifications. This also includes the factors that impact these outcomes, e.g., support in place or disclosure. | 44 | 6 | 3 |

| Disclosure Experiences and Impact | These relate to experiences around disclosure of neurodivergent status and the impact it has on neurodivergent individuals. | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Mental Health and Wellbeing | These relate to questions around the mental health and wellbeing of neurodivergent students and staff, including the impact of university work and access to mental health specific support. | 14 | 7 | 5 |

| Neurodivergent Staff | These relate to university staff who are neurodivergent and include topics such as support and career progression. | 9 | 6 | 6 |

| Prevalence Estimates | These relate to the number of neurodivergent individuals within universities (staff and students) and the proportion of students diagnosed during pursuit of their degree. | 5 | 4 | 2 |

| Staff Awareness of Neurodiversity | These relate to staff knowledge and understanding of neurodiversity. | 16 | 3 | 3 |

| Student Experience | These relate to the wider university experience for neurodivergent students, i.e., beyond teaching and learning, such as induction, social life and housing. | 7 | 5 | 4 |

| Support | These relate to how neurodivergent students experience university support and evidence for certain support approaches and effectiveness. | 82 | 16 | 9 |

| Teaching and Learning | These relate to teaching and learning practices for neurodivergent students, both in terms of preferences and effectively supporting learning. | 41 | 14 | 7 |

| The University Community | These relate to the wider community, e.g., attitudes of other students towards neurodiversity and sense of belonging. | 26 | 13 | 8 |

| Interim Priority Setting Top Ranked Questions | Rationale |

|---|---|

| How much do university staff understand about neurodivergence, the challenges it may bring for students, and the accommodations that may help, and therefore adjust their practice? | Consensus |

| What barriers exist to accessing mental health support at universities for neurodivergent students? | Consensus |

| How do factors such as diagnosis, disclosure, treatment, and support impact degree outcomes for neurodivergent students? | Consensus |

| Do neurodivergent graduates have different employment prospects compared to neurotypical students? | Neurodivergent |

| What teaching methods are most effective for neurodivergent students? | Consensus |

| What adjustments to assessment (e.g., coversheets, extensions) help neurodivergent students and ensure equity? | Consensus |

| Should neurodivergent and neurotypical students be graded against different criteria? | Neurodivergent |

| What interventions or supports are most useful for neurodivergent staff? | Neurodivergent |

| Are neurodivergent students more likely to drop out of study, require resits or interrupt their studies compared to neurotypical students? | Neurodivergent |

| Do neurodivergent students perform better or worse than neurotypical students on certain types of assessment? | Neurodivergent |

| What types of assessment and/or adjustments to assessment are preferred by neurodivergent students? | Neurodivergent |

| To what extent do neurodivergent staff and students feel that their university is accessible, and what factors impact this? | Neurodivergent |

| What are staff attitudes towards neurodivergent students and how do these impact student outcomes? | Neurodivergent |

| What are neurodivergent student experiences of support systems within universities, including both advantages and disadvantages of received support? | Neurodivergent |

| Are university wellbeing and mental health support services trained in supporting neurodivergent students? | Neurodivergent |

| What is the impact of neurodivergency on access to careers and career progression for university staff? | Neurodivergent |

| How does time blindness impact adherence to deadlines in neurodivergent students? | Neurodivergent |

| Priority | Research Priority |

|---|---|

| 1 | How much do university staff understand about neurodivergence, the challenges it may bring for students, and the accommodations that may help, and therefore adjust their practice? (C) |

| 2 | How do factors such as diagnosis, disclosure, treatment, and support impact degree outcomes for neurodivergent students? (C) |

| 3 | What are staff attitudes towards neurodivergent students, and how do these impact student outcomes? (N) |

| 4 | Are university wellbeing and mental health support services trained in supporting neurodivergent students? (N) |

| 5 | What adjustments to assessment (e.g., coversheets, extensions) help neurodivergent students and ensure equity? (C) |

| 6 | What teaching methods are most effective for neurodivergent students? (C) |

| 7 | To what extent do neurodivergent staff and students feel that their university is accessible, and what factors impact this? (N) |

| 8 | Are neurodivergent students more likely to drop out of study, require resits or interrupt their studies compared to neurotypical students? (N) |

| 9 | Do neurodivergent students perform better or worse than neurotypical students on certain types of assessment? (N) |

| 10 | What are neurodivergent student experiences of support systems within universities, including both advantages and disadvantages of received support? (N) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Le Cunff, A.-L.; Ross, F.; Westwood, S.J.; Koya, S.; Caldwell, D.M.; Russell, A.E.; Dommett, E.J. Key Research Questions to Support Neurodiversity in Higher Education: A Participatory Priority Setting Exercise. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070839

Le Cunff A-L, Ross F, Westwood SJ, Koya S, Caldwell DM, Russell AE, Dommett EJ. Key Research Questions to Support Neurodiversity in Higher Education: A Participatory Priority Setting Exercise. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):839. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070839

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe Cunff, Anne-Laure, Faith Ross, Samuel J. Westwood, Sumeiyah Koya, Deborah M. Caldwell, Abigail E. Russell, and Eleanor J. Dommett. 2025. "Key Research Questions to Support Neurodiversity in Higher Education: A Participatory Priority Setting Exercise" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070839

APA StyleLe Cunff, A.-L., Ross, F., Westwood, S. J., Koya, S., Caldwell, D. M., Russell, A. E., & Dommett, E. J. (2025). Key Research Questions to Support Neurodiversity in Higher Education: A Participatory Priority Setting Exercise. Education Sciences, 15(7), 839. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070839