Socio-Emotional Competencies for Sustainable Development: An Exploratory Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Question and Objectives

- (a)

- To analyze the SEL interventions presented in the selected publications, as well as the strengths, limitations, and missing points of the SEL interventions.

- (b)

- To establish actionable recommendations to develop socio-emotional skills (SESs) based on the facets of the Big Five personality traits.

2.2. Data Source and Search Strategy

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Overview of SEL Interventions

3.2. Intervention Results

3.2.1. Overall Analysis of the Interventions

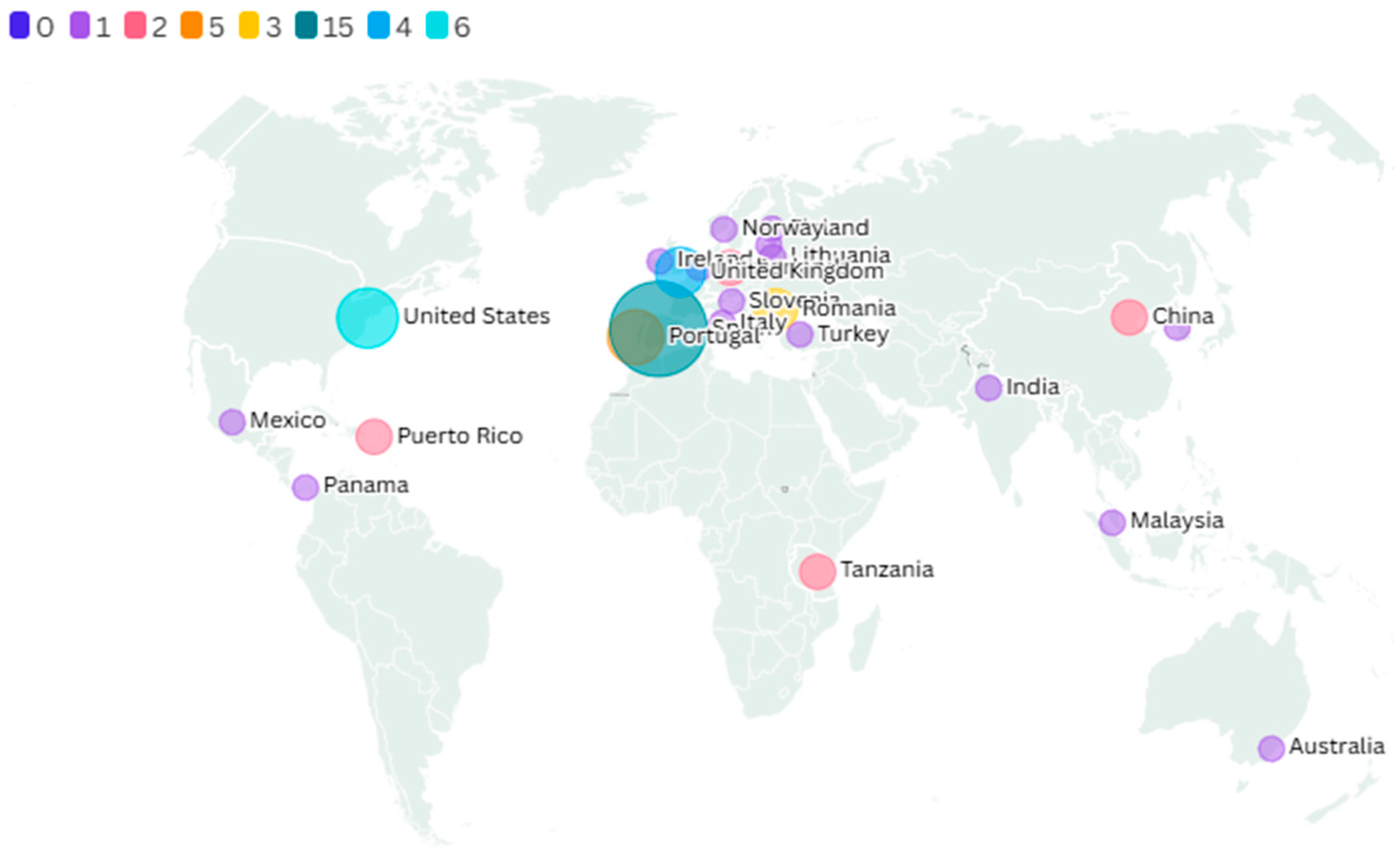

- Regarding the cultural context, most publications tend to evaluate programs from a particular cultural perspective. The question is: Is that a matter of different program objectives or a different cultural perspective (taking the context into account)? A notable difference can be seen in the intended benefits of SEL training between European and Hispanic American countries. In the former, issues related to integration and multiculturalism are emphasized, to the extent that failing to consider these factors may produce negative effects for some students (Van De Sande et al., 2022). In Hispanic American countries, SEL interventions are perceived as effective tools to reduce teenage pregnancy, bullying, and sexual violence, while promoting equity and respect between boys and girls (Araúz-Ledezma et al., 2022);

- The analyzed actions show that SEL interventions have a significant impact on the development of SESs, particularly self-concept, empathy, and motivation. They also help reduce anxiety, providing strong support in coping with academic stress. These interventions have a positive effect in reducing bullying behavior and peer violence, and contribute to improving communication skills. The increase in behavioral adjustment among adolescents leads to a significant improvement in the school climate (Veríssimo et al., 2022; Cherewick et al., 2021a; Cejudo et al., 2020; Cojocaru, 2023; Amutio et al., 2020; Sweetman, 2021; Rodríguez-Ledo et al., 2018; Martín-Moya et al., 2018; Avivar-Cáceres et al., 2022; Song & Kim, 2022; Araúz-Ledezma et al., 2022; Vestad & Tharaldsen, 2022; Sousa et al., 2023; Cuéto-López et al., 2022).

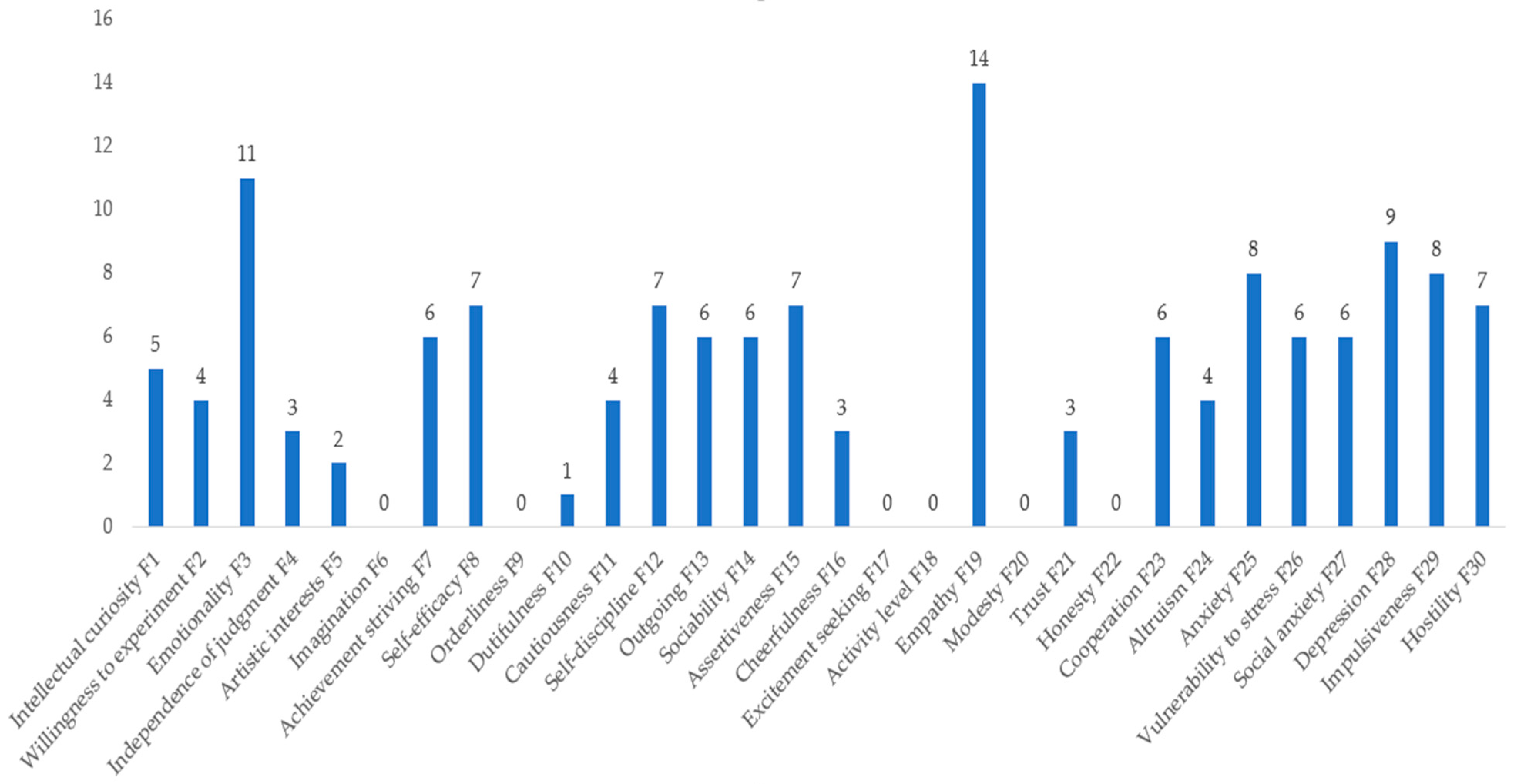

- The emotional dysregulation factor—which includes the facets of Anxiety, Vulnerability to stress, Social Anxiety, Depression, Impulsiveness, and Hostility—was by far the most addressed in the analyzed publications. A striking number of programs equate SEL training with actions for mental health promotion and prevention in that field, including suicide prevention (Muela et al., 2021), depression prevention or improvement (Sáez-Santiago & Torres Arroyo, 2016), relief from anorexia nervosa (Rodríguez-Ledo et al., 2018) etc., placing SEL and mental health education nearly on the same level;

- There are high expectations regarding SEL effectiveness that are not always met, as shown in articles analyzing program implementation experiences that have resulted in adverse or counterproductive effects. The lived experience of youth participants is often omitted in research (Evans et al., 2015). For this reason, the potential for interventions to generate unintended or adverse effects has not been theoretically or empirically explored. Based on a qualitative case study on student participation in an SEL intervention—specifically, the Student Assistance Program (Evans et al., 2015)—four iatrogenic processes were identified, meaning that unintended and generally harmful effects resulted from the intervention: (1) The way schools select participating students can be perceived as a negative label, leading to rejection by peers. (2) Failing in the SEL program may be used by students as a means to improve social status, but maintaining that status requires continued resistance to the intervention. (3) When the SEL intervention focuses on reversing the specific behaviors commonly used by a tight-knit peer group as a means of cohesion, members may prioritize their friendship over the program and reinforce the targeted behaviors. (4) Students may seek to reposition themselves within specific peer groups by boasting or reinforcing anti-school behaviors, which leads to an amplification of deviance.

- E.

- Interesting associations are found between SEL programs and the development of positive emotions, which in many cases is linked to the reduction or self-regulation of problematic internet use, cyberbullying prevention, and related behaviors (Laakso et al., 2023).

- F.

- Regarding problematic internet use, it is worth noting that it is more prevalent among boys and is associated with poorer socio-emotional health (Chen et al., 2021; Marín-López et al., 2020; Coelho et al., 2017). Girls show better outcomes (Ogurlu et al., 2018), which is reflected in a slightly more pronounced effect of the intervention among girls compared to boys (Laakso et al., 2023).

- G.

- Several publications focus on the professionals facilitating the SEL intervention—both to assess the adequacy of their training as psychologists or teachers (Deli et al., 2021; Sáez-Santiago & Torres Arroyo, 2016), and to observe whether prior training leads to improvements in the teaching of social skills in the classroom (Berg et al., 2021), or whether there are school-related factors that influence the implementation of the program (Gràcia et al., 2022). Additionally, the degree of teacher adherence to delivering the lessons within an intervention was identified as a parallel objective to the main focus of the research (Neth et al., 2020).

- H.

- In examining the implementation of SEL to improve academic performance, some publications were related to social support for gifted students (Ogurlu et al., 2018), the relationship between learning anxiety and school dropout (Deli et al., 2021), and its influence on academic stress (Vestad & Tharaldsen, 2022), as well as its relevance for athlete training (Hebard et al., 2021). The direct relationship between SEL and overall academic achievement is also addressed (Amutio et al., 2020; Portela-Pino et al., 2021). In low-income countries, SEL implementation has been analyzed as a means of achieving flexible distance learning (Cherewick et al., 2021b).

- I.

- It is surprising that we found only one publication linking SEL with the arts. Specifically, it explores whether participation in a visual arts program at a museum can produce positive transfer effects on specific socio-emotional levels and certain skills (Kastner et al., 2021). The same applies to animal-assisted interventions, of which we identified only one within our sample (Muela et al., 2021).

3.2.2. Analysis of the First Final Sample

3.2.3. Analysis of the Second Final Sample

3.2.4. Analysis of the Third Final Sample

3.2.5. Actionable Recommendations (Objective 2)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OCEAN | Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, Neuroticism |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SEL | Social and emotional learning, socio-emotional learning |

| SESs | Social and emotional skills or competencies, socio-emotional skills or competencies |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

References

- Abad-Villaverde, B., Matos Lluberes, P. C., Acra, C., & Lendor, W. (2022). El legado del COVID-19 a la educación superior desde la mirada del desarrollo sostenible. Aula Revista de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales, 68(2), 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Hadi, N. H., Midin, M., Tong, S. F., Chan, L. F., Mohd Salleh Sahimi, H., Ahmad Badayai, A. R., & Adilun, N. (2023). Exploring Malaysian parents’ and teachers’ cultural conceptualization of adolescent social and emotional competencies: A qualitative formative study. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 992863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amutio, A., López-González, L., Oriol, X., & Pérez-Escoda, N. (2020). Predicción del rendimiento académico a través de la práctica de relajación-meditación-mindfulness y el desarrollo de competencias emocionales. Universitas Psychologica, 19, 1–17. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/journal/647/64762919019/html/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Arango Benítez, P. A., Orjuela Roa, C. H., Buitrago Roa, A. F., & Lesmes Martínez, O. M. (2024). Importancia de las habilidades socioemocionales en la educación: Una revisión documental. RHS-Revista Humanismo y Sociedad, 12(2), 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araúz-Ledezma, A. B., Massar, K., & Kok, G. (2022). Implementation of a school-based social emotional learning program in Panama: Experiences of adolescents, teachers, and parents. International Journal of Educational Research, 115, 101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine of Hippo. (1904). Epistulae ex duabus epistularum collectionibus additis aliquot miscellaneis. In E. Goldbacher (Ed.), Corpus scriptorum ecclesiasticorum latinorum (Volume 44). Epistle 167, 2, 4–5. F. Tempsky/G. Freytag. [Google Scholar]

- Avivar-Cáceres, S., Prado-Gascó, V., & Parra-Camacho, D. (2022). Effectiveness of the FHaCE Up! Program on school violence, school climate, conflict management styles, and socio-emotional skills on secondary school students. Sustainability, 14(24), 17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azrak, A. (2020). El discurso psicológico en el campo educativo: Una revisión crítica de su configuración histórica y su devenir actual. Foro de Educación, 18(2), 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, Á. (2016). Desarrollo positivo adolescente desde la perspectiva personal. Relación con variables sociodemográficas, contextuales y rendimiento académico [Doctoral dissertation, Universidad de Zaragoza]. [Google Scholar]

- Balaguer, Á. (2023). La estructura del carácter. In Desarrollo de la identidad y el buen carácter en el siglo XXI (pp. 53–77). (C. Naval., J. L. Fuentes., & L. D. Rojas, Coords.). Dykinson. [Google Scholar]

- Balaguer, Á., & Berkowitz, M. W. (2021). El modelo PRIMED como innovación para la educación no formal. In Investigación e innovación educativa frente a los retos para el desarrollo sostenible (pp. 578–590). (J. A. Marín, J.-C. de la Cruz-Campos, S. Pozo, & G. Gómez, Coords.). Dykinson. [Google Scholar]

- Barcia Cedeño, E. I., Tambaco Quintero, A. R., Obando Burbano, M. d. l. Á., Barcia Garófalo, Á. R., & Valverde Prado, N. G. (2024). Sostenibilidad y educación integral: Revisión sistemática de modelos educativos transformadores para sociedades resilientes. LATAM Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, 5(6), 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios Tao, H., Peña Rodríguez, L. J., & Cifuentes Bonnet, R. (2019). Emociones y procesos educativos en el aula: Una revisión narrativa. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte, 58, 202–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, M., Talvio, M., Hietajärvi, L., Benítez, I., Cavioni, V., Conte, E., & Lonka, K. (2021). The development of teachers’ and their students’ social and emotional learning during the “Learning to Be Project”-Training course in five European countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 705336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisquerra, R. (2006). Educación emocional y bienestar. Praxis. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, A., Papaioannou, D., & Sutton, A. (2012). Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Boussemart, J.-P., Leleu, H., Shen, Z., & Valdmanis, V. (2017). Performance analysis for three pillars of sustainability. IÉSEG working paper series 2017-EQM-01. Available online: https://www.ieseg.fr/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/2017-EQM-01_Shen.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Canals-Sans, J., Hernández-Martínez, C., Sáez-Carles, M., & Arija-Val, V. (2018). Prevalence of DSM-5 depressive disorders and comorbidity in Spanish early adolescents: Has there been an increase in the last 20 years? Psychiatry Research, 268, 328–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejudo, J., Losada, L., & Feltrero, R. (2020). Promoting social and emotional learning and subjective well-being: Impact of the “aislados” intervention program in adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and PUBLIC health, 17(2), 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C., Yang, C., & Nie, Q. (2021). Social-emotional learning competencies and problematic internet use among Chinese adolescents: A structural equation modeling analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherewick, M., Lebu, S., Su, C., Richards, L., Njau, P. F., & Dahl, R. E. (2021a). Promoting gender equity in very young adolescents: Targeting a window of opportunity for social emotional learning and identity development. BMC Public Health, 21, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherewick, M., Lebu, S., Su, C., Richards, L., Njau, P. F., & Dahl, R. E. (2021b). Study protocol of a distance learning intervention to support social emotional learning and identity development for adolescents using interactive mobile technology. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 623283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunchi Orellana, M. P., & Ordóñez Vásquez, M. E. (2024). Educación socioemocional como herramienta del proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje en los estudiantes de 1ro de Bachillerato. Revista Tecnológica ESPOL (RTE), 36(1), 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codina, L., Lopezosa, C., & Freixa Font, P. (2021). Scoping reviews en trabajos académicos en comunicación: Frameworks y fuentes. In A. Larrondo Ureta, K. Meso Ayerdi, & S. Peña Fernández (Eds.), Información y big data en el sistema híbrido de medios-XIII congreso internacional de ciberperiodismo (pp. 67–85). Universidad del País Vasco. [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, V., Sousa, V., & Figueira, A. P. (2014). The impact of a school-based social and emotional learning program on the self-concept of middle school students. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 19(2), 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, V., Sousa, V., Raimundo, R., & Figueira, A. (2017). The impact of a Portuguese middle school social–emotional learning program. Health Promotion International, 32(2), 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, S. (2023). Transformative social and emotional learning (t-sel): The experiences of teenagers participating in volunteer club activities in the community. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(6), 4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomeischi, A. A., Duca, D. S., Bujor, L., Rusu, P. P., Grazzani, I., & Cavioni, V. (2022a). Impact of a school mental health program on children’s and adolescents’ socio-emotional skills and psychosocial difficulties. Children, 9(11), 1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colomeischi, A. A., Ursu, A., Bogdan, I., Ionescu-Corbu, A., Bondor, R., & Conte, E. (2022b). Social and emotional learning and internalizing problems among adolescents: The mediating role of resilience. Children, 9(9), 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa-Lareo, M.-D. (2025). Entre pantallas y pensamientos: Hacia una educación reflexiva en entornos digitales [Between screens and thoughts: Towards a reflective education in digital environments]. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 37(1), 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuéto-López, J., Franco-Paredes, K., Bautista-Díaz, M. L., & Santoyo Telles, F. (2022). Programa de prevención universal para factores de riesgo de trastornos alimentarios en adolescentes mexicanas: Un estudio piloto. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 9(1), 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deli, W., Kaur, A., & Awang Hashim, R. (2021). Who delivers it and how it is delivered: Effects of social-emotional learning interventions on learning anxiety and dropout intention. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction (MJLI), 18(1), 1–27. Available online: http://mjli.uum.edu.my/index.php/cur-issues#a1 (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J. (2008). From panopticon to pan-psychologization or, why do so many women study psychology? International Journal of Žizek Studies, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- De Vos, J. (2016). ¿Dónde está la educación en la neuroeducación? (Trad. David Pavón-Cuéllar). Teoría y Crítica de la Psicología, 8, 1–16. Available online: https://www.teocripsi.com/ojs/index.php/TCP/article/view/153 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Díaz López, A., Rubio Hernández, F. J., & Carbonell Berna, N. (2019). Efectos de la aplicación de un programa de inteligencia emocional en la dinámica de bullying: Un estudio piloto. Revista de Psicología y Educación, 14(2), 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Gómez, A., Enesco, C. S., Pérez-Albéniz, A., & Pedrero, E. F. (2022). Suicidal behavior assessment in adolescents: Validation of the SENTIA-brief scale. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatria, 49(1), 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domitrovich, C. E., Durlak, J. A., Staley, C. C., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Social-emotional competence: An essential factor for promoting positive adjustment and reducing risk in school children. Child Development, 88(2), 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, M. R., Tillman, R., & Luby, J. (2020). Early socioemotional competence, psychopathology, and latent class profiles of reparative prosocial behaviors from preschool through early adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 32(2), 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dowling, K., & Barry, M. M. (2020). Evaluating the implementation quality of a social and emotional learning program: A mixed methods approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durlak, J. A., Mahoney, J. L., & Boyle, A. E. (2022). What We know, and what we need to find out about universal, school-based social and emotional learning programs for children and adolescents: A review of meta-analyses and directions for future research. Psychological Bulletin, 148(11–12), 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecclestone, K., & Hayes, D. (2009). The dangerous rise of therapeutic education. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M. J., Kranzler, A., Parker, S. J., Kash, V. M., & Weissberg, R. P. (2014). The complementary perspectives of social and emotional learning, moral education, and character education. In L. P. Nucci, D. Narváez, & T. Krettenauer (Eds.), Handbook of moral and character education (pp. 272–289). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, R., Scourfield, J., & Murphy, S. (2015). The unintended consequences of targeting: Young people’s lived experiences of social and emotional learning interventions. British Educational Research Journal, 41(3), 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiss, R., Dolinger, S. B., Merritt, M., Reiche, E., Martin, K., Yanes, J. A., Thomas, C. M., & Pangelinan, M. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of school-based stress, anxiety, and depression prevention programs for adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(9), 1668–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Pedrero, E., Pérez-Albéniz, A., Al-Halabí, S., Lucas-Molina, B., Ortuño-Sierra, J., Díez-Gómez, A., Pérez-Sáenz, J., Inchausti, F., Valero García, A. V., García, A. G., Solana, R. A., Ródenas-Perea, G., De Vicente Clemente, M. P., López, A. C., & Debbané, M. (2023). PSICE project protocol: Evaluation of the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment for adolescents with emotional symptoms in school settings. Clínica y Salud, 34(1), 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, L., Midford, R., Cahill, H., Buergelt, P. T., Robinson, G., Leckning, B., & Paton, D. (2020). Enhancing social and emotional wellbeing of Aboriginal boarding students: Evaluation of a social and emotional learning pilot program. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furedi, F. (2004). Therapy culture: Cultivating vulnerability in an uncertain age. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gamage, K., & de Silva, E. (2022). Sustainable development: Embedding sustainability in higher education. In N. Gunawardhana, & K. A. A. Gamage (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of sustainability in higher education learning and teaching (pp. 1–9). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- González-Salamanca, J. C., Agudelo, O. L., & Salinas, J. (2020). Key competences, education for sustainable development and strategies for the development of 21st century skills. A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 12(24), 10366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gràcia, M., Alvarado, J. M., & Nieva, S. (2022). Autoevaluación y toma de decisiones para mejorar la competencia oral en educación secundaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación-e Avaliação Psicológica, 1(62), 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara Pérez, E. (2009). ¿Por qué Ética y educación ambiental para el desarrollo sostenible? Ingeniería industrial. Actualidad y Nuevas Tendencias, I(2), 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Hansmann, R., Mieg, H. A., & Frischknecht, P. (2012). Principal sustainability components: Empirical analysis of synergies between the three pillars of sustainability. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 19(5), 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A., Stavri, P., & Tchanturia, K. (2021). Individual and group format adjunct therapy on social emotional skills for adolescent inpatients with severe and complex eating disorders (CREST-A). Neuropsychiatrie, 35, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatchimonji, D. R., Vaid, E., Linsky, A. C., Nayman, S. J., Yuan, M., MacDonnell, M., & Elias, M. J. (2022). Exploring relations among social-emotional and character development targets: Character virtue, social-emotional learning skills, and positive purpose. International Journal of Emotional Education, 14(1), 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebard, S. P., Oakes, L. R., Davoren, A. K., Milroy, J. J., Redman, J., Ehrmann, J., & Wyrick, D. L. (2021). Transformational coaching and leadership: Athletic administrators’ novel application of social and emotional competencies in high school sports. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 14(3), 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete-Alcocer, N., López-Ruiz, V. R., Alfaro-Navarro, J. L., & Nevado-Peña, D. (2024). The role of environmental, economic, and social dimensions of sustainability in the quality of life in Spain. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 19, 1997–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isohätälä, J., Näykki, P., & Järvelä, S. (2020). Cognitive and socio-emotional interaction in collaborative learning: Exploring fluctuations in students’ participation. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 64(6), 831–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Morales, M. I., & López Zafra, E. (2009). Inteligencia emocional y rendimiento escolar: Estado actual de la cuestión. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 41(1), 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- John, O. P., Naumann, L. P., & Soto, C. J. (2008). Paradigm shift to the integrative Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and conceptual issues. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 114–158). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kals, E., & Müller, M. (2014). Education for sustainability: Moral issues in ecology education. In L. P. Nucci, D. Narváez, & T. Krettenauer (Eds.), Handbook of moral and character education (pp. 471–487). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kastner, L., Umbach, N., Jusyte, A., Cervera-Torres, S., Fernández, S. R., Nommensen, S., & Gerjets, P. (2021). Designing visual-arts education programs for transfer effects: Development and experimental evaluation of (digital) drawing courses in the art museum designed to promote adolescents’ socio-emotional skills. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 603984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, H., König, H. H., & Konnopka, A. (2020). The excess costs of depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristjánsson, K. (2018). Virtuous emotions. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kristjánsson, K. (2020). Flourishing as the aim of education: A neo-aristotelian view. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Laakso, M., Fagerlund, Å., Pesonen, A. K., Figueiredo, R. A., & Eriksson, J. G. (2023). The impact of the positive education program flourishing students on early adolescents’ daily positive and negative emotions using the experience sampling method. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 43(4), 385–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M. Y., Leichtenstern, K., Kriegel, M., Enz, S., Aylett, R., Vannini, N., Hall, L., & Rizzo, P. (2011). Technology-enhanced role-play for social and emotional learning context–Intercultural empathy. Entertainment Computing, 2(4), 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas-Molina, B., Pérez-Albéniz, A., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2018). The potential role of subjective wellbeing and gender in the relationship between bullying or cyberbullying and suicidal ideation. Psychiatry Research, 270, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machado Pérez, Y. (2022). Origen y evolución de la educación emocional. Alternancia. Revista de Educación e Investigación, 4(6), 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-López, I., Zych, I., Ortega-Ruiz, R., Hunter, S. C., & Llorent, V. J. (2020). Relations among online emotional content use, social and emotional competencies and cyberbullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 108, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Agut, M. P. (2018). Educación y competencia socioemocional en la educación para la sostenibilidad. In Educación en la sociedad del conocimiento y desarrollo sostenible: XXXVII Seminario interuniversitario de teoría de la educación (pp. 225–232). (M. C. Barroso Jerez, Coord.). Universidad de La Laguna. [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Moya, R., Ruiz-Montero, P. J., Chiva-Bartoll, Ò., & Capella-Peris, C. (2018). Motivación de logro para aprender en estudiantes de educación física: Diverhealth. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 52(2), 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masschelein, J., & Simons, M. (2014). Defensa de la escuela. Una cuestión pública. Miño y Dávila. [Google Scholar]

- Mayo Lara, D., Bocardo Valle, A., & Rendón Hernández, R. J. (2023). Educación y sustentabilidad: Hacia un futuro sostenible. LATAM Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, 4(6), 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1999). Una teoría de cinco factores de la personalidad. In L. A. Pervin, & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 139–153). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, R. R., & John, O. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60, 175–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckay, F. (2016). Eudaimonia and culture: The anthropology of virtue. In J. Vittersø (Ed.), Handbook of eudaimonic well-being. International handbooks of quality-of-life. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, G. (2009). Quality of life and sustainability: Toward person–environment congruity. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(3), 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muela, A., Balluerka, N., Sansinenea, E., Machimbarrena, J. M., García-Ormaza, J., Ibarretxe, N., Eguren, A., & Baigorri, P. (2021). A social-emotional learning program for suicide prevention through animal-assisted intervention. Animals, 11(12), 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulraney, M., Coghill, D., Bishop, C., Mehmed, Y., Sciberras, E., Sawyer, M., Efron, D., & Hiscock, H. (2021). A systematic review of the persistence of childhood mental health problems into adulthood. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 129, 182–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K. (2012). The social pillar of sustainable development: A literature review and framework for policy analysis. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 8(1), 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neth, E. L., Caldarella, P., Richardson, M. J., & Heath, M. A. (2020). Social-emotional learning in the middle grades: A mixed-methods evaluation of the strong kids program. RMLE Online, 43(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, R. I., Yim, O., & Shaenfield, D. E. (2020). Gender and ethnicity: Are they associated with differential outcomes of a biopsychosocial social-emotional learning program? International Journal of Yoga, 13(1), 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novo, M. (2009). El desarrollo sostenible. Su dimensión ambiental y educativa. Editorial Universitas S.A. [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo, J. C. (2019). Sobre lo “neuro” en la neuroeducación: De la psicologización a la neurologización de la escuela. Sophia: Colección de la Educación, 26(1), 141–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2015). Skills for social progress: The power of social and emotional skills. OECD Skills Studies, OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2021). Beyond academic learning: First results from the survey of social and emotional skills. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogurlu, Ü., Sevgi-Yalın, H., & Yavuz-Birben, F. (2018). The relationship between social–emotional learning ability and perceived social support in gifted students. Gifted Education International, 34(1), 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olderbak, S., & Wilhelm, O. (2020). Overarching principles for the organization of socioemotional constructs. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 29(1), 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portela-Pino, I., Alvariñas-Villaverde, M., & Pino-Juste, M. (2021). Socio-emotional skills in adolescence. influence of personal and extracurricular variables. International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health, 18(9), 4811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primi, R., Santos, D., John, O. P., & De Fruyt, F. (2021). SENNA inventory for the assessment of social and emotional skills in public school students in Brazil: Measuring both identity and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 716639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purvis, B., Mao, Y., & Robinson, D. (2019). Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustainability Science, 14(3), 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, M., Cueli-Naranjo, M. d. l. Á., & Nieuwenhuys-Ruiz, V. (2024). Revisión y valoración de políticas de prevención e intervención en salud mental infanto-juvenil en centros educativos. Informe ejecutivo. Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ledo, C., Orejudo-Hernández, S., Celma-Pastor, L., & Jesus Cardoso-Moreno, M. (2018). Improving social-emotional competencies in the secondary education classroom through the SEA program. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 16(3), 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancassiani, F., Pintus, E., Holte, A., Paulus, P., Moro, M. F., Cossu, G., Angermeyer, M. C., Carta, M. G., & Lindert, J. (2015). Enhancing the emotional and social skills of the youth to promote their wellbeing and positive development: A systematic review of universal school-based randomized controlled trials. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health, 26(11), 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santomauro, D. F., Mantilla Herrera, A. M., Shadid, J., Zheng, P., Ashbaugh, C., Pigott, D. M., Abbafati, C., Adolph, C., Amlag, J. O., Aravkin, A. Y., Bang-Jensen, B. L., Bertolacci, G. J., Bloom, S. S., Castellano, R., Castro, E., Chakrabarti, S., Chattopadhyay, J., Cogen, R. M., Collins, J. K., … Ferrari, A. J. (2021). Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet, 398(10312), 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz Leal, M., Orozco Gómez, M. L., & Toma, R. B. (2022). Construcción conceptual de la competencia global en educación. Teoría De La Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 34(1), 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez-Santiago, E., Rodríguez-Ocasio, G., & Rodríguez-Hernández, N. (2013). Aceptación al programa estrategias para mantener un ánimo saludable (EMAS): Un programa de prevención de la depresión para adolescentes. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 47(2), 329–337. [Google Scholar]

- Sáez-Santiago, E., & Torres Arroyo, J. (2016). Viabilidad de un programa de prevención de la depresión facilitada por maestras en Puerto Rico. Revista Puertorriqueña de Psicología, 27(2), 368–380. [Google Scholar]

- Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2017). Social and emotional learning and teachers. The Future of Children, 27(1), 137–155. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/44219025 (accessed on 1 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A. (2022). Character & social-emotional development (CSED) national guidelines. Character.org. [Google Scholar]

- Shinde, S., Pereira, B., & Khandeparkar, P. (2022). Acceptability and feasibility of the Heartfulness way: A social-emotional learning program for school-going adolescents in India. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(5), 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidera, F., Rostan, C., Collell, J., & Agell, S. (2019). Application of a socioemotional and moral learning program for promoting healthy relationships in secondary education. Universitas Psychologica, 18(4), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé Blanch, J., & Moyano Mangas, S. (2017). La colonización Psi del discurso educativo. Foro de Educación, 15(23), 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., Salazar de Pablo, G., Il Shin, J., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2022). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(1), 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. M., & Kim, S. (2022). Effects of a social and emotional competence enhancement program for adolescents who bully: A quasi-experimental design. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, C. J., John, O. P., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2011). Age differences in personality traits from 10 to 65: Big Five domains and facets in a large cross-sectional sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), 330–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, V., Silva, P. R., Romão, A. M., & Coelho, V. A. (2023). Can an universal school-based social emotional learning program reduce adolescents’ social withdrawal and social anxiety? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 52(11), 2404–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sweetman, N. (2021). “I thought it was my fault just for being born”. A Review of an sel programme for teenage victims of domestic violence. Education Sciences, 11(12), 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2015). Replantear la educación. ¿Hacia un bien común mundial? Ediciones UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000232697 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- UNESCO. (2017). La educación al servicio de los pueblos y el planeta: Creación de futuros sostenibles para todos. Informe de Seguimiento de la Educación en el mundo 2016. Ediciones UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248526 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- UNESCO. (2022). Berlin declaration on education for sustainable development. German Commission for UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000381228 (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- UNESCO. (2024). Aportes para la enseñanza de habilidades socioemocionales. Estudio regional comparativo y explicativo (ERCE 2019). UNESCO Office Santiago and Regional Bureau for Education in Latin America and the Caribbean. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000388352/PDF/388352spa.pdf.multi (accessed on 23 November 2024).

- Urrea-Monclús, A., Rodríguez-Pérez, S., Sala-Roca, J., & Zárate-Alva, N. E. (2021). Instrumentos psicoeducativos para la intervención en pedagogía social: Validación criterial del test situacional desarrollo de competencias socioemocionales de jóvenes (DCSE-J). Pedagogía Social, 37, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, T. J. (2020). Activities for flourishing: An evidence-based guide. Journal of Positive Psychology & Wellbeing, 4(1), 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Sande, M. C., Fekkes, M., Diekstra, R. F., Gravesteijn, C., Reis, R., & Kocken, P. L. (2022). Effects of an SEL program in a diverse population of low achieving secondary education students. Frontiers in Education, 6, 744388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegas, M. I., & Mateos-Agut, M. (2023). Comer en familia: Su relación con la comunicación familiar y la agresividad de los adolescentes. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 10(3), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, L., Castro, I., Costa, M., Dias, P., & Miranda, F. (2022). Socioemotional skills program with a group of socioeconomically disadvantaged young adolescents: Impacts on self-concept and emotional and behavioral problems. Children, 9(5), 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vestad, L., & Tharaldsen, K. B. (2022). Building social and emotional competencies for coping with academic stress among students in lower secondary school. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 66(5), 907–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigelsworth, M., Lendrum, A., & Humphrey, N. (2013). Assessing differential effects of implementation quality and risk status in a whole-school social and emotional learning programme: Secondary SEAL. Mental Health & Prevention, 1(1), 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willen, S. S. (2022). Flourishing and health in critical perspective: An invitation to interdisciplinary dialogue. SSM—Mental Health, 2, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C., Chen, C., Lin, X., & Chan, M. K. (2021). School-wide social emotional learning and cyberbullying victimization among middle and high school students: Moderating role of school climate. School Psychology, 36(2), 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaldívar Sansuán, R. (2024). Críticas constructivas a la educación emocional. Teoría de la Educación. Revista Interuniversitaria, 36(1), 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factors | Facets |

|---|---|

| Open-mindedness | Intellectual Curiosity, Boldness/Action, Emotionality/Feelings, Independence of Judgment/Values, Esthetic Sensitivity, and Imagination |

| Skill performance | Need for Achievement, Competence, Order, Sense of Duty, Deliberation, and Self-Discipline |

| Commitment to others | Amiability, Gregariousness, Assertiveness, Positive Emotions/Joy, Thrill or Sensation Seeking, and Activity Level |

| Collaboration | Sensitivity to Others/Empathy, Modesty, Trust, Openness, Cooperation, and Altruism |

| Emotional dysregulation | Anxiety, Vulnerability to Stress, Social Anxiety, Depression, Impulsiveness, and Hostility |

| “social and emotional skill*” OR “social-emotional skill*” OR “socioemotional skill*” OR “socio-emotional skill*” OR “social emotional skill*” OR “habilidades socioemocionales” OR “social and emotional learning” OR “social-emotional learning” OR “socioemotional learning” OR “socio-emotional learning” OR “social emotional learning” OR “aprendizaje socioemocional” OR “social and emotional competenc*” OR “social-emotional competenc*” OR “socioemotional competenc*” OR “socio-emotional competenc*” OR “social emotional competenc*” OR “competencias socioemocionales” OR “social and emotional abilit*” OR “social-emotional abilit*” OR “socioemotional abilit*” OR “socio-emotional abilit*” OR “social emotional abilit*” OR “habilidades socioemocionales” OR “SEL” | |

| AND | |

| “middle school” OR “high school” OR “secondary school” OR “secondary education” OR “teen*” OR “adolescen*” OR “bachillerato” OR “educación secundaria” | |

| AND | |

| “program*” OR “training” OR “interven*” OR “project*” OR “proyecto*” |

| Categories | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Field of knowledge | Educational Sciences, Health Sciences | Other fields |

| Educational setting | Formal education | Non-formal and informal education |

| Population age | 12–16 y.o. | Outside the age range |

| Year of publication | Since 2010 | Prior to 2010 |

| Type of publication | SEL research, experiences, case studies | Books, book chapters, theses, theoretical articles, essays, dissertations |

| Condition | Peer-reviewed journal papers | Conference proceedings, chapters, books, doctoral theses, dissertations, reports |

| Language | English or Spanish | Other languages |

| No. | Publication | Facet | Country | Sample y.o. | Objective | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Veríssimo et al. (2022) | F1 F3 | Portugal | 12 | Evaluate the effectiveness of a program promoting SESs among socio-culturally vulnerable adolescents. | Impact on self-concept. Increase in behavioral adjustment, happiness, and satisfaction. Reduction in anxiety. |

| 2 | Ogurlu et al. (2018) | F1 F8 F14 F21 F26 | Turkey | 10–14 | Examine the relationship between SESs and perceived social support among gifted students. | Perceived social support can improve the socio-emotional skills of gifted students. |

| 3 | Abd Hadi et al. (2023) | F1 F3 F14 F15 F19 F24 | Malaysia | - | Explore the conceptualization of SESs among parents and teachers to determine culturally sensitive SEL constructs for Malaysian adolescents. | Correlation between SESs and social support. Gifted students saw close friends and teachers as important sources of support. |

| 4 | Cherewick et al. (2021a) | F1 F7 F8 F12 F19 F23 F24 | Tanzania | 10–11 | Evaluate the potential of an SEL intervention for very young adolescents to improve mindset and SESs. | Crucial SEL topics and subtopics for Malaysian adolescents align with CASEL’s five competency domains. CASEL’s relationship and decision-making domains reflect Asian cultural values. |

| 5 | Cherewick et al. (2021b) | F1 F3 F13 F23 | Tanzania | 10–14 | Create SEL experiences and flexible distance learning opportunities in low-income countries. | Significant improvements in socio-emotional mindset and skills (generosity, curiosity, growth mindset, perseverance, purpose, and teamwork). Experiential learning in small groups with community and parent involvement showed greater effects. |

| 6 | Hatchimonji et al. (2022) | F2 F7 F8 F24 | USA | 11–16 | Test the relationships between the objectives of the SECD approach (Social–Emotional and Character Development) for character development. | Technology can be leveraged to create SEL experiences and offer flexible learning opportunities in low-income countries. |

| 7 | Cejudo et al. (2020) | F2 F3 F25 F28 | Spain | 12–17 | The five character virtues are associated with purpose and SEL, providing empirical support for the SECD intervention framework. | |

| 8 | Cojocaru (2023) | F2 F16 F23 F25 | Romania | 13–18 | Evaluate the effects of a program through the video game “Aislados” aimed at improving subjective well-being, mental health, and emotional intelligence. | Participation in group activities strengthens group identity and can promote optimism through social recognition. It fosters patience, tolerance, and empathy, allowing adolescents to develop socially, assume responsibility, solve problems, improve self-management, and learn to listen, and it also provides emotional stability. It also improves academic performance and reduces disruptive behaviors. |

| 9 | Amutio et al. (2020) | F3 | Spain | 12–16 | Investigate to what extent participation in school-organized projects for vulnerable and disadvantaged groups contributed to the development of Transformative SEL (T-SEL) in adolescents. | Statistically significant differences in health-related quality of life, positive affect, and mental health. |

| 10 | Chen et al. (2021) | F3 F12 F29 | China | 16 | Explore the relationships between REMIND (relaxation, meditation, and mindfulness), emotional competence, and academic performance in adolescents. | Participation in school club activities stimulated and developed T-SEL competencies among adolescents. |

| 11 | Marín-López et al. (2020) | F3 F15 F16 | Spain | 13–14 | Understand problematic internet use (PIU) among adolescents and the associations between SEL competencies and PIU through an integrated and hierarchical model. | A high level of SESs was negatively related to cybervictimization and cyberperpetration, and was associated with a greater use of emotional content online. The use of more emotional content online was associated with greater cybervictimization and cyberperpetration. A high level of SESs also protected against cyberbullying, but excessive use of emotions online was a risk factor. |

| 12 | Coelho et al. (2014) | F2 F3 F19 F23 | Portugal | 12–15 | Explore the relationship between SESs, online emotional content, cybervictimization, and cyberperpetration. | REMIND’s influence on academic performance is indirect, mediated by emotional competencies. Teachers are encouraged to implement REMIND-based practices to enhance emotional competencies and academic performance. |

| 13 | Sweetman (2021) | F3 F8 F12 F15 F19 | Ireland | 12–14 | Male students reported higher levels of general PIU and more problematic time management. SEL competencies were negatively associated with PIU. Emphasis on promoting SEL competencies to prevent PIU. | |

| 14 | Donohue et al. (2020) | F3 F14 F19 | USA | 5–14 | Investigate whether a universal SEL program would promote academic, social, and emotional self-concept. It analyzes differences by gender and among students with lower initial self-concept. | A high level of social and emotional competencies was negatively associated with both cybervictimization and cyberperpetration. Exposure to more emotional online content was associated with higher cybervictimization and cyberperpetration. |

| 15 | Rodríguez-Ledo et al. (2018) | F3 F15 F19 | Spain | 11–14 | Explore the impact of domestic violence on adolescent victims through the lens of SEL. | Increases were observed in social, emotional, and overall self-concept, which remained stable over two years and across genders—except in emotional self-concept, where only boys showed benefits. Students with low levels of self-awareness benefited more than their peers in academic and social self-awareness. |

| 16 | Harrison et al. (2021) | F4 F21 F26 F27 | United kingdom | 8–18 | Early preventive intervention. | Thematic analysis showed a reduction in shame and guilt, increased self-esteem and self-efficacy, greater participation in education and recreation, and improved family relationships. |

| No. | Publication | Facet | Country | Sample y.o. | Objective | Main results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | Portela-Pino et al. (2021) | F4 F5 F11 | Spain | 11–18 | Evaluate the impact of an emotional competencies development program based on the SEA theoretical model (emotional attention and understanding, emotional regulation and repair, and emotional expression). | SES deficits in the preschool period promote deteriorated reparative response trajectories. Early preventive interventions should focus on understanding emotions, social functioning, maladaptive guilt, and psychiatric symptoms. |

| 18 | Urrea-Monclús et al. (2021) | F4 F8 | Spain | 12–17 | Describe how to adapt Cognitive Remediation and Emotion Skills Training (CREST) for use with adolescents with anorexia nervosa in an emergency hospital setting. | Improvement in SEL, especially related to adaptive emotional expression in social contexts. Improvements were also noted in empathy and social adjustment. |

| 19 | Kastner et al. (2021) | F5 | Germany | 12–19 | Analyze the relationship between SEL and sex, physical activity index, after-school attendance, and type of after-school activities. | Good acceptability with Patient Satisfaction. Patients showed medium-sized improvements in socio-emotional functioning components. |

| 20 | Martín-Moya et al. (2018) | F7 | Spain | 17–18 | Validate the DCSE-J (Situational Test for the Development of Socio-emotional Competence in Youth), based on peer evaluation. | Students who participated in extracurricular activities scored higher in social awareness. Artistic and musical activities were associated with SESs, while sports activities were not. |

| 21 | Van De Sande et al. (2022) | F7 F8 F10 F11 | The Netherlands | 14–19 | Design and evaluate a visual arts education program based on production theory, to investigate whether it generates positive effects on specific SESs and levels. | Students most frequently nominated by peers also scored higher. Girls were nominated more often and obtained higher scores. Mastering more complex competencies requires mastering more basic ones. The results supported the validity of the test. |

| 22 | Hebard et al. (2021) | F7 F8 | USA | - | Identify motivational variations according to goal-setting theory using the innovative program DiverHealth. | A visual expression approach improved recognition of emotions, perspectives, and self-expression, particularly in vulnerable students. The results support the effectiveness of visual arts programs in enhancing SESs. |

| 23 | Yang et al. (2021) | F11 F12 F14 F19 | USA | 12–18 | Evaluate the effectiveness of the S4L (Skills4Life) SEL program for education. | Differences in motivational variables. Girls in the experimental group scored higher than boys. Personalized tutoring may improve student motivation. |

| 24 | Berg et al. (2021) | F11 F19 F25 F26 F29 F30 | Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovenia, Spain | 12–15 | Capture the lived experiences of coaches (Athletic Administrators, AAs) applying a novel SEL-based program (InsideOut Initiative, ISOI) with coaches and student athletes in secondary school sports. | The results highlight the importance of promoting student well-being, especially through social awareness and relationship skills, as a goal of SEL programs. |

| 25 | Colomeischi et al. (2022a) | F12 F25 F28 F29 F30 | Romania | 4–16 | Examine associations between students’ perceptions of four core SESs (responsible decision-making, social awareness, self-management, and relationship skills), school climate, and cyberbullying experience. | The PROMEHS program improves SESs and well-being, prevents behavioral problems, and reduces psychosocial difficulties. Improvements in self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relational skills, and responsible decision-making. |

| 26 | Newman et al. (2020) | F12 F23 F25 F29 | USA | 14–16 | Evaluate teacher and student readiness for SEL during an intervention. | Experienced compared to students taught by regular teachers. Changes are needed in the socio-cultural approach of the Skills4Life program and in teacher training. |

| 27 | Colomeischi et al. (2022b) | F12 F25 F28 | Romania | 11–18 | Investigate the effectiveness of the school-based PROMEHS program (Mental Health Promotion in Schools) designed to foster learning and prevent psychosocial difficulties. | The coach–athlete relationship mediated the connection between sports participation and character, health, and well-being outcomes for student athletes. AAs in secondary schools can provide leadership, mentorship, and direction to help coaches enhance student athletes’ performance and human development. |

| 28 | Shinde et al. (2022) | F13 | India | 11–15 | Investigate the outcomes of a biopsychosocial SEL intervention based on yogic breathing, across gender and ethnicity. | Cyberbullying victimization (CBV) was negatively associated with responsible decision-making and self-management, and positively associated with social awareness. The negative association with self-management and CBV was stronger when the school climate was more positive; the link between CBV and responsible decision-making was mitigated by the school climate. The strongest association was between CBV and self-management. |

| 29 | Gràcia et al. (2022) | F13 | Spain | 12–16 | Deepen the understanding of how SEL, resilience, and internalizing problems (personal/internal impacts) are related, focusing on the mediating role of resilience. | Results indicated favorable development in some measured skills in the intervention group, though effects varied between the two age groups. |

| 30 | Avivar-Cáceres et al. (2022) | F13 F14 F15 F19 | Spain | 11–17 | Present a qualitative evaluation of the Heartfulness Way, a socio-emotional program for secondary schools based on mindfulness techniques delivered by teachers. | Results indicated that the PROMEHS program was effective in improving SESs across all school levels and reducing internalizing problems. |

| 31 | Song & Kim (2022) | F13 F14 F15 F19 | South Korea | 12–16 | Analyze an Intelligent Pedagogical Assistance System (SIAP) designed to support teachers in planning, assessing, and guiding participatory lessons that foster oral competence. | Significant effects of the program on social competence, emotional regulation, empathy, and bullying behavior at the 1-month follow-up. |

| 32 | Araúz-Ledezma et al. (2022) | F13 F19 F29 F30 | Panama | 12–15 | Evaluate the effectiveness of the FHACE-up! program for training in communication and social skills. | Significant improvements were found in all seven measured outcomes. The biopsychosocial approach was associated with positive SEL outcomes across all genders and ethnic groups. |

| No. | Publication | Facet | Country | Sample y.o. | Objective | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33 | Franck et al. (2020) | F15 F23 F24 | Australia | 13–15 | Develop a program to improve SESs for adolescents who engage in bullying, and investigate its effects on bullying behavior and mental health. | Results show that resilience mediates the relationship between self-awareness and internalizing problems, between self-management and internalizing problems, and between responsible decision-making and internalizing problems. |

| 34 | Laakso et al. (2023) | F16 | Finland | 10–12 | Identify levels of fidelity and integrity, and explore enabling and limiting factors faced during the SEL intervention. | Overall, participants strongly supported the mindfulness-based curriculum. Students reported positive responses, prosocial behavior, self-acceptance, and supportive relationships. |

| 35 | Díaz López et al. (2019) | F19 | Spain | 12–13 | Indicators showed that as teachers achieved instructional goals, students’ oral competence improved. A questionnaire also revealed increased self-concept related to students’ communication skills in the intervention group. | |

| 36 | Lim et al. (2011) | F19 | United kingdom, Germany | 13–14 | Evaluate an SEL program for internal Aboriginal youth and identify contextual factors affecting its effectiveness. | Results showed significant improvement in school violence, the perception of the school climate, and communication skills. |

| 37 | Coelho et al. (2017) | F19 F27 F29 | Portugal | 11–17 | Examine changes in students’ daily positive and negative emotions through participation in the Flourishing Students program. | The program had a significant positive impact on adolescents’ perception of violence and the school climate. |

| 38 | Muela et al. (2021) | F21 F26 F28 | Spain | 14–17 | Evaluate the effectiveness of an emotional intelligence program in improving the school climate, reducing bullying, and developing emotional skills. | The effects of the program were significant on social competence, emotional regulation, empathy, and bullying behavior at the one-month follow-up. The SECE program was effective in reducing bullying behavior among adolescents. |

| 39 | Neth et al. (2020) | F25 F27 F28 F29 F30 | USA | 11–13 | Educate on intercultural empathy using ORIENT (role-playing technology). Present the prototype and evaluation. | The program was highly accepted by students, teachers, and parents. Key enablers included innovation, responsiveness to local needs, lesson adaptability, and program acceptability. Barriers included time constraints, cultural transferability, and organizational context. |

| 40 | Deli et al. (2021) | F25 F26 | China | 14 | Investigate the effectiveness of a universal school-based SEL program and compare different implementation formats. | Improvements were seen in students who sought and offered help, worked in groups, handled conflicts, were assertive, and discussed cultural topics. |

| 41 | Vestad & Tharaldsen (2022) | F26 | Norway | 13–14 | Pilot and evaluate the OverCome-AAI program, using animal-assisted interventions for young people at high risk of suicidal behavior. | The intervention buffered increases in negative daily emotions. Participants experienced positive changes such as reduced loneliness and higher levels of calm and enjoyment of solitude. The effect was stronger among girls. |

| 42 | Sousa et al. (2023) | F27 | Portugal | 12–14 | Evaluate the impact of Strong Kids, an SEL curriculum in a middle school, on students’ symptoms. | The program improved the school climate and reduced bullying, while enhancing motivation and empathy. Emotional education was presented as a preventive tool for school coexistence issues in adolescence. |

| 43 | Wigelsworth et al. (2013) | F27 | United Kingdom | 11–12 | Investigate the effectiveness of two types of SEL interventions delivered by different types of teachers, to reduce learning anxiety and intention to drop out. | ORIENT software offers a new framework for role-playing and storytelling that enables users to interact with virtual social actors to promote intercultural empathy. It uses tangible interaction modalities to increase user motivation to learn about the culture of others and collaborate effectively. |

| 44 | Evans et al. (2015) | F27 F30 | United Kingdom | 12–14 | Explore how participants experienced relationship skills, emotional regulation, mindfulness, growth mindset, and problem solving when facing academic stress. | Positive results in social awareness, self-control, self-esteem, social isolation, and social anxiety. The pre-taught format led to better outcomes in self-esteem and social isolation. |

| 45 | Sáez-Santiago & Torres Arroyo (2016) | F28 | Puerto Rico | 12–14 | Analyze the effectiveness of a program on social withdrawal and social anxiety, and the role of individual perceptions of school climate. | Reductions in suicidal ideation, suicide plans, and non-suicidal self-harm, along with increased help-seeking. Reduction in emotional pain intensity, though no changes in despair or depression indicators. The program effectively reduced suicidal behavior in residential youth at high risk. |

| 46 | Cuéto-López et al. (2022) | F28 | Mexico | 12–15 | Evaluate the impact of the SEAL secondary school program on students with low, average, and high SESs (at-risk students). | Strong Kids improved students’ socio-emotional knowledge and reduced internalizing symptoms. However, no significant changes were observed in externalizing symptoms. |

| 47 | Sáez-Santiago et al. (2013) | F28 | Puerto Rico | 12 | Explore the theoretical foundations of the SAP (Student Assistance Program), assess dissemination and implementation levels, and analyze participants’ experiences. | Psychology teachers were more effective in improving SEL knowledge, while regular teachers were more effective in reducing learning anxiety. |

| 48 | Sidera et al. (2019) | F29 | Spain | 14 | Evaluate the viability of a teacher-delivered depression prevention program for adolescents in public schools in Puerto Rico. | Students experienced mindfulness, problem-solving, and the growth mindset as helpful. Emotional regulation and relationship skills were harder to use. More practical exercises are needed for these competencies. |

| 49 | Vegas & Mateos-Agut (2023) | F30 | Spain | 14–18 | Describe the effect of an interactive universal prevention program on disordered eating, body dissatisfaction, thin-ideal internalization, nutrition knowledge, anxiety, and depression. | Analyses showed positive results in reducing social withdrawal and social anxiety. Students with more positive teacher–student relationships benefited more from the intervention. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arbués, E.; Abad-Villaverde, B.; Costa-París, A.; Balaguer, Á.; Conesa-Lareo, M.-D.; Beltramo, C. Socio-Emotional Competencies for Sustainable Development: An Exploratory Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070831

Arbués E, Abad-Villaverde B, Costa-París A, Balaguer Á, Conesa-Lareo M-D, Beltramo C. Socio-Emotional Competencies for Sustainable Development: An Exploratory Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):831. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070831

Chicago/Turabian StyleArbués, Elena, Beatriz Abad-Villaverde, Ana Costa-París, Álvaro Balaguer, María-Dolores Conesa-Lareo, and Carlos Beltramo. 2025. "Socio-Emotional Competencies for Sustainable Development: An Exploratory Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070831

APA StyleArbués, E., Abad-Villaverde, B., Costa-París, A., Balaguer, Á., Conesa-Lareo, M.-D., & Beltramo, C. (2025). Socio-Emotional Competencies for Sustainable Development: An Exploratory Review. Education Sciences, 15(7), 831. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070831