1. Introduction

1.1. ChatGPT in Arts Teaching

The convergence of New Technologies (NT) and the Arts forms a new framework for the existing understanding of how art is produced and shared. NT and generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) applications, along with the rapid development of computer programming systems, have led to the ever-increasing development of machine learning language models that can understand and produce text in a human-like way. Machine learning language models are systems that, in order to understand and produce text, analyze the language’s patterns and structures by interacting with users and using a “training” database. One such example is ChatGPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), an advanced machine learning model that was first made available to the general public in November 2022, experiencing rapid popularity and attracting millions of users. The main advantage of ChatGPT is its ability to rapidly generate lifelike texts in response to users’ text-based questions.

Although seemingly unconnected—since art is linked to the human creative mood—GenAI applications such as ChatGPT have a potential relationship with the arts, such as literature and theatre, since they provide new possibilities for the expression of human creativity. For instance, ChatGPT can create impressive descriptions, narratives, or even poems; in the field of theatre, it can also contribute to creating scripts and developing dialogues (

Haleem et al., 2022;

Mizumoto & Eguchi, 2023). However, this dynamic also raises several concerns, such as issues regarding the authenticity of creation and the safeguarding of human, personal expression (

C. Guo et al., 2023). Alongside concerns about authenticity and personal expression, a particularly critical issue that arises when using generative AI tools such as ChatGPT in the arts is that of intellectual and creative property. The use of GenAI in content creation raises fundamental questions about the ownership and rights of creative works. In traditional artistic and educational contexts, authorship is clear and directly attributed to the human creator. However, when artworks, texts, or educational materials are produced or co-produced with the help of artificial intelligence, the boundaries of authorship and ownership become blurred.

Specifically, questions arise as to whether a work created by artificial intelligence can be considered the intellectual property of the person who initiated it, the developer of the artificial intelligence, or whether it remains completely outside the current legal framework. Indeed, if we take into account that generative AI draws and synthesizes data from a certain database, issues arise regarding the intellectual property of the original content from which the new content is reconstructed. Since the database is not always visible at present, there is no reference to the original creator, while concerns also arise about the possible standardization of art, as the results often resemble each other. In the context of art education, these issues become even more intense. When students or teachers use ChatGPT to create poems, scripts, or course material, questions arise about who owns the copyright, who is responsible for possible plagiarism, and whether the creative result can truly be considered original (

Elbanna & Armstrong, 2023;

Rahman & Watanobe, 2023;

Smits & Borghuis, 2022).

The aforementioned rapid technological progress has confronted contemporary education with new challenges but also with diverse possibilities. The evolution of GenAI and its applications has created new perspectives on the way humans interact with machines, and among these interactions, the field of education could not remain unaffected. This finding is reinforced by the advent of ChatGPT and other GenAI applications that create new pedagogical perspectives and risks (

Dimeli & Kostas, 2025;

Fokides & Peristeraki, 2025;

Kostas & Chanis, 2024). As NTs and now GenAI applications are diffusing into everyone’s lives, they are therefore coming to affect education as well, with teachers being asked to adapt to the new, modern digital reality of the 21st century and the challenges that accompany it (

Dimeli & Kostas, 2025).

In this context, this study aims to investigate primary and secondary school teachers’ beliefs about the pedagogical use of ChatGPT in arts subjects such as literature, music, theatre, and art—a field in which there is a significant gap in the literature, given the recent nature of GenAI applications. Specifically, the study intends to investigate, according to

Ajzen’s (

1991) Theory of Planned Behavior, teachers’ beliefs that influence their intention to utilize ChatGPT in art classes.

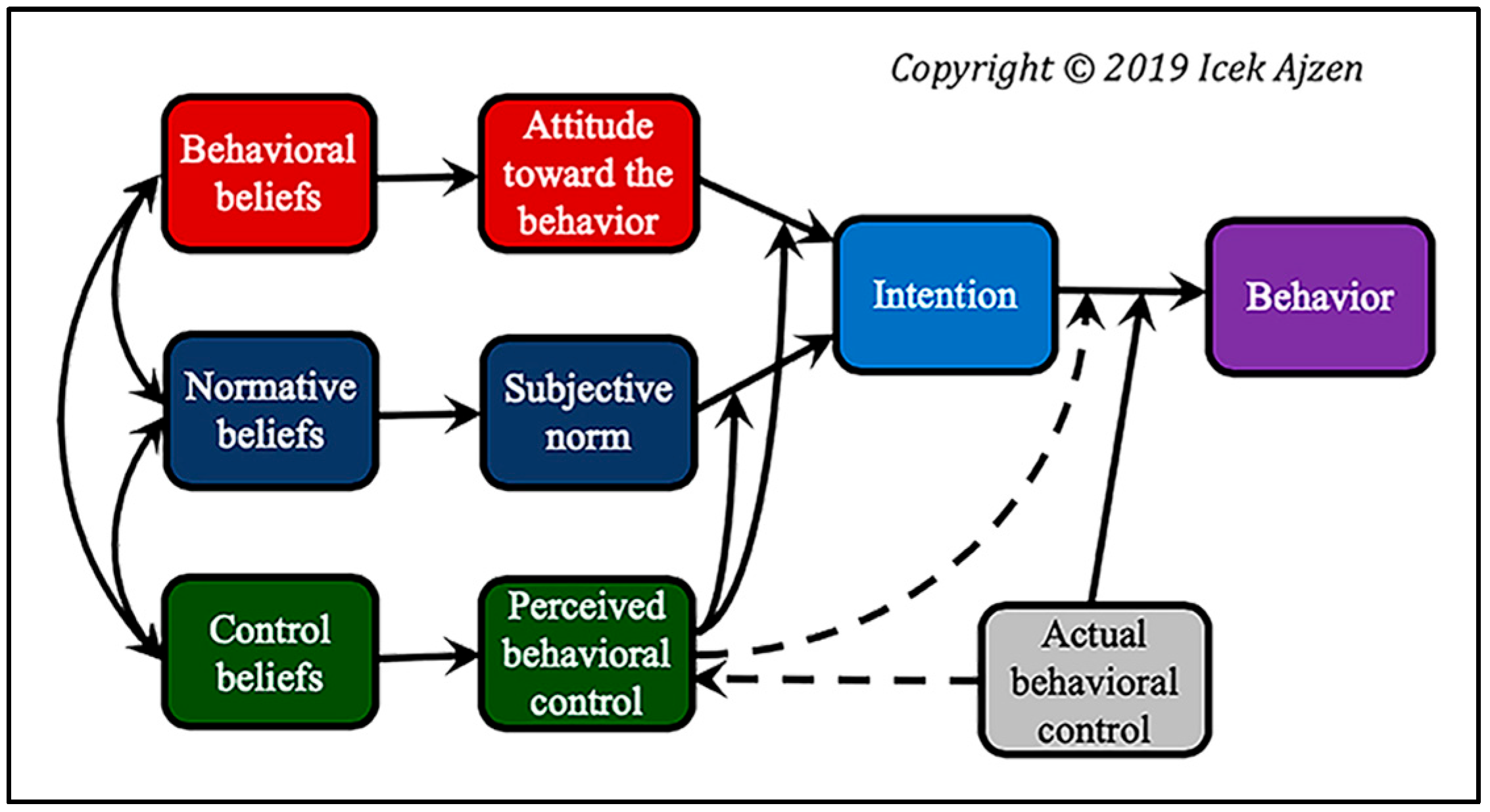

As mentioned above,

Ajzen’s (

1991) Theory of Planned Behavior was chosen to investigate teachers’ beliefs, according to which behavior is determined by behavioral intentions that form a network shaped by attitudes toward behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. This theory has been used many times to interpret and evaluate teachers’ beliefs regarding the introduction and use of technological tools (

Kan & Fabrigar, 2017;

Ajzen, 1991).

As stated in the categorical framework of its creator, beliefs can be divided into behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, and control beliefs. Behavioral beliefs relate to attitudes toward behavior, the intention that precedes behavior, and shape the subjective norm, the perceived control of behavior. On the other hand, normative beliefs are those on the basis of which a person believes that they should or should not perform a behavior. In other words, it is a person’s perception of social normative pressures or the beliefs of others about behaviors that should or should not be performed. Based on these, the individual’s subjective norm is formed, i.e., their perception of the behavior in question, which is influenced by the judgment of “significant others,” such as parents, managers, and colleagues. Finally, control beliefs are related to the presence of factors that can facilitate or hinder the manifestation of a behavior and determine the perceived control of the behavior, that is, the perceived ease or difficulty of the individual to perform it. Perceived control is determined by control beliefs and is related to self-efficacy (

Ajzen, 1991). So, based on the above categories of beliefs arising from

Ajzen’s (

1991) Theory, which is used to investigate teachers’ beliefs about NT tools, were formulated the main questions asked to teachers (

Figure 1). In the context of educational innovation, and specifically the adoption of GenAI tools such as ChatGPT, the Theory of Planned Behavior provides a robust lens for analyzing teachers’ intentions and actions. It enables the systematic examination of how teachers’ attitudes towards GenAI, the expectations and pressures from their professional and social environment, and their perceived control over its use determine their willingness to integrate such technologies into their teaching practice.

1.2. Studies and Research Contribution

The involvement of children in the arts during their leisure time has shown significant benefits for their overall development and engagement (

Koulianou et al., 2025;

Mastrothanasis & Kladaki, 2020;

Mastrothanasis et al., 2025a,

2025b), making it essential to explore technological tools like ChatGPT that could further enhance their creative experiences. In order to investigate both teachers’ and students’ beliefs about the pedagogical use of ChatGPT and its role in motivating English language learning,

Ali et al. (

2023) administered online questionnaires (

n = 80) in school settings. The results showed that both students and teachers had a neutral attitude regarding the effect that ChatGPT can have on listening and speaking skills. However, teachers agreed that teaching involving ChatGPT can provide learning motivation to students. It is worth noting that this research was conducted just a few months after ChatGPT was made widely available, reflecting the early stage of empirical research in this field.

Further studies focusing on school contexts have emphasized the dual nature of teachers’ beliefs regarding the use of GenAI in the classroom. On the one hand, educators recognize the value of such tools in enhancing student engagement, creativity, and the overall learning process (

Dimeli & Kostas, 2025;

Fokides & Peristeraki, 2025;

Kostas & Chanis, 2024). On the other hand, they frequently express concerns related to the authenticity of student work, potential copying, reduced critical thinking, and issues surrounding ethical use and data privacy (

Ali et al., 2023). Despite these concerns, some teachers remain optimistic, highlighting the potential of GenAI to motivate students and support more innovative and differentiated teaching approaches.

The study by

Chen et al. (

2025) employed a cross-sectional survey design to collect data from teachers in a large urban school district in the United States. A total of 1454 K-12 teachers participated, responding to both closed- and open-ended questions regarding their experiences, perceptions, and concerns about generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) tools, including ChatGPT, in their teaching practice. The sample included teachers from various disciplines, among which were teachers of the arts (language arts, literature, creative writing, music, and visual arts). Analysis included both quantitative and qualitative methods, allowing for the identification of domain-specific perspectives.

According to the findings, teachers in the arts disciplines expressed both potential and reservations concerning the use of generative AI tools like ChatGPT in their instruction. A number of arts teachers reported that generative AI could support the process of writing, idea generation, and creative activities. Respondents noted that tools such as ChatGPT might assist students in brainstorming ideas for creative writing assignments, poems, and stories, as well as help them overcome writer’s block or generate alternative phrasings and perspectives. Some teachers mentioned that GenAI could serve as a useful scaffold for students who struggle with creative expression or have difficulty starting assignments.

Despite recognizing these affordances, teachers in the arts also raised substantial concerns about the use of GenAI in their subjects. The issue of academic honesty was particularly prominent. Many teachers worried that students might use ChatGPT or similar tools to generate entire essays, poems, or creative projects, thereby bypassing genuine creative effort and undermining the educational goals of their courses. They expressed fears that such practices could lead to increased plagiarism and a decline in original student work. Teachers also voiced concerns regarding the impact on students’ creative and critical thinking skills. There was apprehension that frequent use of GenAI could foster overreliance on automated assistance, impeding the development of authentic creative abilities and the willingness to engage deeply with artistic processes. Some respondents noted that, in the arts, personal voice, style, and emotional investment are fundamental, and there was skepticism about whether GenAI could support or respect these essential elements. Furthermore, teachers highlighted the risk of misinformation or inaccuracies in AI-generated content, especially in creative or artistic contexts where nuance, intent, and cultural references are significant. They emphasized the importance of teacher guidance to ensure that students use GenAI tools ethically and responsibly. Several arts teachers called attention to the need for clear guidelines and policies regarding the use of GenAI in creative assignments. They requested professional development to help them understand both the capabilities and limitations of these tools and to equip them with strategies for teaching students to use GenAI as a supplementary resource rather than a substitute for their own creativity.

In addition,

Bergdahl and Sjöberg (

2025) conducted a cross-sectional study involving 312 K-12 teachers from Sweden. Data were collected through a comprehensive questionnaire that included both closed and open-ended items. The teachers represented various subjects, with 28% indicating that they taught “Arts and aesthetics”. The study aimed to explore teachers’ attitudes, perceptions, and self-efficacy regarding the use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools, specifically chatbots like ChatGPT, in educational practice.

Teachers of “Arts and aesthetics” provided a diverse set of views concerning the integration of AI tools such as ChatGPT into their teaching. Many expressed an overall positive attitude toward the potential of AI in education. They saw value in using chatbots for inspiration and as a means to create engaging learning materials, particularly in creative and artistic domains.

Several arts teachers noted that AI tools could facilitate creative processes by offering new ideas and perspectives for artistic expression. For instance, they mentioned that chatbots might help students generate prompts or overcome creative blocks in activities like creative writing, music composition, or visual arts projects. Some teachers described how AI could be used to support lesson planning, giving them more time to focus on direct interaction with students and the development of artistic skills.

However, teachers also highlighted several concerns and limitations regarding the use of AI in the arts. A prominent concern was the potential impact on originality and authenticity in students’ work. Teachers worried that excessive reliance on AI-generated content could diminish students’ own creative efforts, leading to less original art or writing. The authenticity of artistic output was seen as a crucial aspect of arts education, and teachers emphasized that AI should not replace personal engagement, imagination, and the development of individual style. Another concern raised was the risk of dependency on technological solutions. Some teachers feared that if students turned too frequently to chatbots for ideas or solutions, then it could hamper their ability to solve creative problems independently. There was also a sense of uncertainty about the quality and appropriateness of AI-generated material, especially in terms of artistic nuance, emotional content, and alignment with educational objectives in the arts. Arts teachers expressed a need for professional development and support to help them better understand the capabilities and limitations of AI tools. Many indicated that they lacked confidence in their own AI skills (“AI self-efficacy”) and wanted more guidance on integrating chatbots into arts education in a meaningful way. They stressed the importance of clear guidelines and best practices to ensure that AI was used to enhance, rather than detract from, the artistic and creative goals of their subjects (

Bergdahl & Sjöberg, 2025).

Overall, the literature in primary and secondary education underlines both the promise and the complexity of integrating GenAI tools like ChatGPT into arts education. Teachers’ perceptions reflect a careful weighing of benefits, such as increased motivation and creativity, against risks related to academic integrity and the changing nature of learning processes. The ongoing expansion of empirical studies in school environments is expected to further clarify these trends and support the development of effective pedagogical practices for GenAI integration.

Although the primary focus of this review is on research conducted in primary and secondary education, it is important to briefly acknowledge findings from the higher education context, as they highlight issues that may also emerge in school settings. For instance,

Mohamed (

2023) investigated the beliefs of ten lecturers at Northern Border University in Saudi Arabia regarding the effectiveness of ChatGPT on students’ English language learning. This study highlighted both supportive and critical attitudes: some lecturers emphasized the usefulness of ChatGPT in providing quick and accurate answers, while others raised concerns about its impact on students’ critical thinking, research skills, and the perpetuation of biases and misinformation.

In contrast,

Iqbal et al. (

2022) conducted semi-structured interviews with 20 higher education teachers in Pakistan, capturing a predominantly negative attitude towards ChatGPT. Participants in this study expressed strong concerns related to copying and plagiarism, although some pedagogical benefits, such as for assessment and programming skills, were also noted. The researchers concluded that there is a need for the training and informing of teaching staff, and further investigation into students’ beliefs.

In the study by

Sáez-Velasco et al. (

2024), five educators in higher arts education participated in a focus group to discuss the use of generative AI in the arts. The educators recognized that generative AI can speed up creative processes, reduce costs, and serve as a useful tool for inspiration or overcoming creative blocks. However, they stressed that AI-generated content often results in more homogeneous and less emotionally nuanced output than human-made art. Educators believed that foundational artistic knowledge and critical capacity are necessary before using AI, and overreliance on AI may hinder the development of personal artistic skills. They also highlighted the need for clear authorship and regulation to distinguish between AI-generated and human-created works. Overall, educators considered AI to be a valuable supplementary tool but not a replacement for human creativity and expertise in arts education.

While these studies originate from the higher education sector and may not directly correspond to the realities of primary and secondary education, they offer valuable insights into broader trends and challenges surrounding the adoption of GenAI in educational contexts. The study of teachers’ beliefs about the pedagogical use of ChatGPT is quite an uncharted field. Given that ChatGPT was recently released, it is to be expected that there are few studies focusing on teachers’ beliefs about this tool and even fewer to nonexistent ones focusing specifically on the dynamic relationship between ChatGPT and arts education. On the one hand, the present study’s contribution lies in the exploration of a hitherto relatively barren research field, and its novelty and originality are focused on the particular interconnection of ChatGPT with teachers’ beliefs about humanities courses involving the arts.

The mapping of teachers’ beliefs is expected to shed research light on the advantages and challenges arising from a possible involvement of this tool in education, and more specifically in arts courses, and to highlight and record the specific expectations, concerns, and worries of the teachers themselves. By knowing teachers’ beliefs, it is possible to create the conditions for the emergence of practices that exploit the potential of ChatGPT and reduce potential risks. Furthermore, analyzing teachers’ beliefs in the field of art allows for a better understanding of the way in which ChatGPT can influence the human creative process, while at the same time evaluating its reception by its final recipients—the users, and in this case, in education, the teachers themselves.

3. Results

3.1. Behavioral Beliefs

The first area of analysis refers to teachers’ behavioral beliefs, according to

Ajzen’s (

1991) theory. In total, 355 references were detected, which were then divided into 2 thematic areas and 20 sub-codes (

Table 1 and

Table 2). This means that, according to

Ajzen’s (

1991) theory, the positive and negative outcomes expected by teachers from the pedagogical use of ChatGPT in the arts were included in this domain.

As the results showed, teachers expressed equally positive (177 reports out of 355, n% = 49.85%) and negative expectations about the pedagogical use of ChatGPT in the arts. In fact, the positive outcomes appear to vary (10 codes). Specifically, the main benefit, as expressed by several teachers, is the improvement of students’ participation, engagement, and activation of their interest in art lessons (n = 51, n% = 14.37%, Participant 28: “I definitely think it will improve students’ engagement in art lessons because all the children are familiar with the technologies”).

Furthermore, the contribution of ChatGPT to research was also noted due to the speed of responses (n = 43, n% = 12.11%, Participant 26: “They would have answers for every question they had. For example, they could ask about a painting or an artwork”).

The teachers also highlighted its potential contribution as an assistant (n = 33, n% = 9.30%) in a variety of ways, such as providing materials, ideas, and exercises, saving time, and creating teaching scenarios. As they reported, it could save them valuable time and help them in organizing lessons (Participant 67: “It would help me in organizing my lessons, giving me ideas and also exercises”).

In addition, there were also reports about ChatGPT’s contribution regarding the improvement of both students’ and teachers’ creativity in lessons involving the arts, such as literature, drama, music, and art (n = 15, n% = 4.23%, Participant 8: “It provides inspiration and original, creative ideas that you find hard to think of on your own”).

Furthermore, there were some references (n = 10, n% = 2.82%) from the teachers about the benefit that could be gained in improving students’ vocabulary and writing skills (Participant 15: “I consider the added value of modifying and correcting texts between ChatGPT and students as the most important benefit”). Equal reports were found (n = 10, n% = 2.82%) regarding the general positive contribution of New Technologies in education and getting students familiar with them in a pedagogical context (Participant 63: “It would act as a motivation to engage with technology, and students would acquire digital skills”). Also, reports (n = 8, n% = 2.25%) of ChatGPT’s beneficial role in developing students’ critical thinking and ability were detected (Participant 41: “Still, through the proper use of AI, it can help the student, the cultivation of critical thinking and reflection”).

On the other hand, there were fewer reports (n = 4, n% = 1.13%) about its positive impact on the development of group collaboration among students to implement art projects, which implies the enhancement of dialogue in the classroom (Participant 18: “It can help in teaching complex topics in the process of group projects, where students”). Few references (n = 2, n% = 0.56%) were also made to themes related to its pedagogical use in the arts to reduce anachronistic perceptions and stereotypes (Participant 2: “They listen, see, read the opinion of a robot who may not have prejudices and stereotypes like others around him”).

Finally, one teacher (

n = 1,

n% = 0.28%) mentioned the help that writing written responses can provide to students with special educational needs and/or disabilities (Participant 55: “

Mostly it can help deaf children because of the AI technology that gives written text so they can read it. Writing can help them”). However, a variety of concerns were also expressed (

n = 178,

n% = 50.14%), which related to several areas (10 total codes), as presented in

Table 2.

Among the concerns, the most frequent was the mention of the potential risk of students using ChatGPT to copy and avoid personal effort when solving exercises and homework assignments (n = 44, n% = 12.39%, Participant 10: “Without a clear orientation of the use of ChatGPT, the results would be disastrous as they would use it purely as a tool for copying and easy solving”). Furthermore, equally strong seems to be, according to the teachers, the possibility that ChatGPT may contribute to the inactivation of thinking and the reduction in students’ critical faculties (n = 36, n% = 10.14%, Participant 7: “Students will become passive, they will stop thinking”). In addition, several concerns (n = 21, n% = 5.92%) were also expressed about the misinformation it may provide (Participant 60: “ChatGPT gives wrong information even in its advanced form in answers that it gives when you ask it something”).

On the other hand, there were also several reports (n = 16, n% = 4.51%) that mentioned a potential risk of reducing students’ creativity in art classes (Participant 24: “There are definitely a lot of negatives that affect my attitude to art lessons at school. For example, there is a risk of resorting to ready-made production, lack of authenticity and creativity, and standardization—and these are just some of the things that come up”).

There were also equal reports (n = 16, n% = 4.51%) about the potential negative impact on students’ participation, engagement, and interest in the course (Participant 1: “It will probably superficially enhance students’ engagement and then they will lose interest”). There was also reference to the potential change in the role of teachers with the entry of ChatGPT into education, particularly in the arts sector (n = 15, n% = 4.23%, Participant 51: “Maybe it will degrade the teacher’s work; our role will be reduced and degraded, I think, in the future”). A minority of reports (n = 12, n% = 3.38%) identified concerns about privacy, the possibility of plagiarism, and copyright infringement in the arts sector (Participant 44: “My concern is about the data that is taken from us and how it can be used by ChatGPT”).

A possible disadvantage of ChatGPT was pointed out as the lack of human communication (n = 9, n% = 2.54%), which was considered by some to be an integral and irreplaceable part of the educational process that cannot be provided through ChatGPT (Participant 13: “I am afraid that there will be an attachment to it, with use for purposes not so desirable, i.e., incomplete communication and classroom discussion with students”).

A smaller percentage of reports (n = 8, n% = 2.25%) were associated with the consequences that students’ use of ChatGPT may have on their reading and writing skills, grammar, syntax, and vocabulary diversity (Participant 66: “Sometimes what is listed as answers is simplistic though and not very helpful in their discourse and in helping students to delve into art issues”). Finally, one teacher (n = 1, n% = 0.28%) mentioned as a disadvantage the standardized nature of the answers given by ChatGPT, which cannot be beneficial and rather takes on a negative connotation for students who are part of the special education and training context (Participant 64: “The disadvantages have to do with the fact that a teaching is entirely based on it without taking into account the individual needs of children, especially those with learning difficulties”).

3.2. Normative Beliefs

The second axis of the analysis refers to teachers’ normative beliefs, which were collected in 296 reports and distributed into 2 themes and 15 codes (

Table 3 and

Table 4). That is, according to

Ajzen’s (

1991) Theory of Planned Behavior, what teachers reported regarding potential support or rejection they might encounter from others was placed in this axis. Based on the results (

Table 3), teachers made several reports of potential acceptance by others (

n = 112,

n% = 37.84). However, of the total reports (

n = 296), reports of acceptance by others (

Table 3) were significantly fewer (37.84% vs. 62.16%) than those of rejection by others (

Table 4).

Specifically, the majority of reports (n = 29, n% = 9.80%) focused on personal indifference to whether others agree with the use of ChatGPT in art classes and emphasized that their decision on whether to use it does not depend on the consent or approval of others (Participant 29: “Since it is a tool that can be used to make the class more engaging or useful for what I want to teach the children, I am not so influenced by the educational community”).

Furthermore, some highlighted the possibility of being met with enthusiastic acceptance by their own students (n = 26, n% = 8.78%, Participant 4: “Students would accept ChatGPT, I believe, with great pleasure as something new”). Reports were also identified (n = 19, n% = 6.42%) of support from individuals in the educational community who are generally in favor of the integration and pedagogical use of New Technologies in education. For instance, one teacher noted (Participant 11), “I believe I will receive support from the educational community and those who support New Technologies”.

Support also seems to be expected from those who see ChatGPT as an important supportive tool in education (n = 18, n% = 6.08%, Participant 20: “Probably positively would be seen by colleagues and the principal as a facilitator”). Several references focused on the support the teacher might receive from those who view ChatGPT with a willingness to innovate in education (n = 13, n% = 4.39%, Participant 40: “It would have huge acceptance, because most people today are into the clichéd way of teaching that is tried and trusted, but in a school that is faltering. We want innovation”).

Finally, some teachers linked its use and acceptance to institutional support (

n = 7,

n% = 2.36%) and to the need for support from the state, with the definition of clear rules of use (Participant 41: “

We need training”). However, teachers also expressed their beliefs regarding the possible resistance they might encounter in their attempts to pedagogically use ChatGPT in lessons involving the arts. More specifically, some factors (

n = 184,

n% = 62.16%) that could contribute to rejection by others were articulated (

Table 4).

Specifically, the main reason for the rejection that teachers believe they may encounter seems to be the lack of knowledge from colleagues, parents, and the wider educational community (n = 39, n% = 13.18%) (Participant 31: “I think I will generally encounter resistance from those who are not familiar”). Equally frequent were references made to the general skeptical attitude of parents towards ChatGPT (n = 34, n% = 11.49%, Participant 11: “Other parents may be suspicious of ChatGPT because of the risks”).

Almost equal reports (n = 33, n% = 11.15%) were also related to rejection by individuals who are, in general, dismissive towards the use of not only GenAI but also New Technologies in general (Participant 15: “In general, there is a reservation in the use of digital media and new technologies in teaching”).

To the above-mentioned factors is added the teacher’s own personal fear of breaking with the ‘important others’—colleagues, parents, principals, students themselves, and the wider educational community in general (n = 25, n% = 8.45%, Participant 17: “It affects the opinion of others, and a lot, because you can’t keep coming to a conflict”). In addition to concerns about parents’ skepticism, a similar code emerged for their colleagues (n = 21, n% = 7.09%, Participant 52: “Most teachers I have dealt with express some reservation, it’s still new, which I would agree with”).

On the other hand, a belief was expressed that there may be rejection from others due to ethical issues that may arise (n = 20, n% = 6.76%, Participant 2: “Clearly others will see it negatively. We already see that our students bring ready-made exercises to every lesson, and we cannot prevent them”). Among the reports, some focused on the resistance that educators may encounter in using ChatGPT in arts classes, regarding the reduction in students’ critical thinking (n = 9, n% = 3.04%) (Participant 33: “There will be resistance from some, mostly out of fear that it replaces critical thinking in humans”) and their creativity.

Fewer reports were found of issues of resistance or indifference from the students themselves (n = 2, n% = 0.68%), who “will take it as a joke”, as noted by Participant 16. Finally, one report was detected from a teacher (n = 1, n% = 0.34%) who mentioned resistance from those who are afraid of any mistakes that ChatGPT might make and discourage its use (Participant 46: “They will see it negatively, because it makes mistakes”).

3.3. Control Beliefs

The third axis of the analysis refers to teachers’ control beliefs (potential facilitators and barriers) about the pedagogical use of ChatGPT in art lessons. In their responses, 367 references were detected, which were divided into two distinct themes and 12 sub-codes, as presented in

Table 5 and also in

Table 6.

According to the above results, teachers made many references to potential factors that could facilitate the use of ChatGPT in education, especially in art classes such as literature, drama, music, and painting (

n = 161,

n% = 43.87). It should be noted that there was an almost equal number of references to helpful factors (

Table 5), as well as to potential barriers (

Table 6,

n = 206,

n% = 56.13).

Specifically, several references were made during the interviews to issues related to the availability of training/resources (n = 57, n% = 15.53%, Participant 26: “We have, I think, enough facilities in the school, so I don’t think we have a problem, so we can use it, we have the resources”).

Furthermore, in several reports (n = 53, n% = 14.44%), the helpful role of institutional support was pointed out, meaning the presence of a clear framework of rules for the use and proper pedagogical exploitation of ChatGPT by students and also by teachers (Participant 52: “It is important, and it will help to put a law framework in AI. With clear instructions and guidance, it would be easier to use it”).

However, the personal confidence of each teacher that they will be able to use ChatGPT in arts lessons was also identified and recorded as a helpful factor (n = 35, n% = 9.54%, Participant 24: “I also feel quite a lot of personal confidence that I can use it myself”). Finally, it seemed that previous positive experiences of teachers (n = 16, n% = 4.36%), both with ChatGPT and other GenAI tools, could help (Participant 25: “I don’t have any experience of using it in the classroom, but I am positively influenced by what I have heard and read. I have even read about risks, and old movies I had seen in the past about AI”).

On the other hand, teachers also mentioned some barriers that they felt might hinder their eventual willingness or desire to use ChatGPT in arts classes (

n = 206,

n% = 56.13%). The references to barriers that were detected were broken down into eight sub-codes, as shown below in

Table 6.

In particular, the lack of knowledge and experience in using ChatGPT in the arts was identified as a key barrier (n = 83, n% = 22.62%, Participant 7: “I don’t know how it can be used for school arts-related lessons and the potential risks of using it”). A second reported barrier (n = 53, n% = 14.44%) is the limited technological access in Greek schools (Participant 10: “Well, let’s be honest. How to use it? Due to the lack of basic and necessary technological tools in Greek schools…”).

Another barrier mentioned by teachers focused on the negative attitude of their own students (n = 19, n% = 5.18%), who either will not treat ChatGPT as a useful educational tool or will not approach it with due attention and seriousness (Participant 23: “Keep in mind as a barrier that students will not engage”). Furthermore, they mentioned negative influence or discouragement from members of the educational community (n = 17, n% = 4.63%). For example, Participant 34: “One barrier I think I will encounter if I go to use ChatGPT in my classroom in art classes is resistance from older colleagues who may not reject it”.

The teachers’ responses also revealed references to barriers that could be caused by personal resistance and distrust of ChatGPT and GenAI in general (n = 15, n% = 4.09%, Participant 4: “One barrier to using it might be me. Well, I know about ChatGPT, but I wouldn’t want it to be used in literature, like in any other art. I’m not convinced it will be useful”).

Fewer reports were also identified about barriers that may exist due to ChatGPT’s own lack of credibility, errors, weaknesses, and failures, which may ultimately discourage its pedagogical use in arts classes (n = 9, n% = 2.45%, Participant 16: “One barrier is also that ChatGPT doesn’t have enough knowledge about the arts and many topics related to the arts”). In addition, teachers reported the difficulty of integrating it into the existing educational system and curriculum as a barrier (n = 8, n% = 2.18%, Participant 13: “A challenge and a barrier is to organize my lesson that way and include ChatGPT in the context of a live art lesson. That, I think, would be a difficulty”). Finally, there were two reports from teachers about concerns regarding privacy and copyright issues that might arise in the pedagogical use of ChatGPT in lessons involving the arts (n = 2, n% = 0.54%) (Participant 41: “As a barrier we could think, I think, about different copyright issues, especially in the field of art and in lessons related to art. There would be an issue with copyright and authors in areas such as painting, music, visual arts, poetry”).

4. Discussion

Moving on to a critical discussion of the research results, it becomes clear that the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) provides a robust framework for interpreting teachers’ intentions and actions regarding the integration of generative AI in arts education. According to

Ajzen (

1991), the TPB posits that intention, the most immediate antecedent of behavior, is shaped by three core components: behavioral beliefs, normative beliefs, and control beliefs. In this study, each of these constructs offers valuable insight into the complexities underlying teachers’ decision-making processes.

4.1. Expected Benefits and Challenges

Moving on to a critical discussion of the research results that emerged, the most important benefit that teachers expect from the use of ChatGPT in the arts is the increase in interest, the strengthening of students’ participation, and, consequently, their greater involvement in the educational process. The above finding is in line with the beliefs of teachers who also participated in

Ali et al.’s (

2023) study and contributed to the expectation of increased engagement and motivation from the use of ChatGPT, while

Elbanna and Armstrong (

2023) and

Kasneci et al. (

2023) also agree with the finding that the pedagogical utilization of ChatGPT in the literature can have multiple benefits for students. Finally, an increase in interest when ChatGPT was integrated into the educational process was also noted by

K. Guo et al. (

2023).

Then, a second main positive that teachers expect from ChatGPT focuses on its contribution to research, given the rapid and often apt responses that they find it provides. This ability, they believe, will act as a stimulant to students’ inquisitiveness and curiosity. Indeed, its potential contribution to research is also identified in the literature, with ChatGPT suggesting unexplored topics, approaches, and research questions, offering new possibilities, particularly in higher education (

Farrokhnia et al., 2023;

Kasneci et al., 2023). Furthermore, the literature review by

Sallam (

2023) also highlighted the tool’s contribution to research through authoring and improving scientific texts. In fact, some teachers who participated in the research of this study also mentioned the possibility of providing information directly. Indeed, despite any erroneous information, ChatGPT has a satisfactory database that can be utilized for research purposes, as confirmed by the research of

Choi et al. (

2023), in which ChatGPT passed law school examinations. Finally, in a study of higher education teachers’ beliefs about ChatGPT,

Mohamed (

2023) recorded their belief that it is highly beneficial for research purposes to provide accurate answers quickly and directly, which was confirmed by the results of this study.

A third positive factor highlighted by teachers was its use as an assistive tool, providing ideas, exercises, and teaching scenarios for arts lessons and saving them valuable time. Indeed, the above statement is repeated in the literature in several studies and is supported by several researchers. For instance,

Kasneci et al. (

2023) report that ChatGPT can provide exercises and problems for students, create lesson scenarios, as well as notes and supporting materials, a finding that is also supported by

Elbanna and Armstrong (

2023).

Lou (

2023) found that teachers who teach English use ChatGPT as an assistant to prepare their teaching and suggest effective teaching strategies, a possibility also highlighted by

Rahman and Watanobe (

2023).

Another benefit, according to the teachers, is the tool’s contribution to increasing students’ creativity in lessons involving the arts. For example, it was reported that, based on ChatGPT’s textual descriptions, students can be inspired and creative, with the tool suggesting or even drafting poems and plays, a belief also reported by

K. Guo et al. (

2023).

Teachers also highlighted the potential benefit for improving students’ reading and writing skills and vocabulary range through the correction of ChatGPT errors and the positive impact of the extensive responses provided by ChatGPT, which often have adequate vocabulary and exemplary structure. However, in

Ali et al.’s (

2023) study, a “neutral attitude” of teachers and students was found toward the effect that ChatGPT can have on listening and speaking skills, while

Kasneci et al. (

2023),

Su et al. (

2023), and

K. Guo et al. (

2023) emphasize that, through syntactic and grammatical corrections, as well as selecting the right questions to engage in dialogue with the tool, students’ writing and reading skills, as well as their argumentative literacy, can be favored. Especially in the arts,

Kangasharju et al. (

2022) report that the ability of such GenAI tools to write poems can be particularly beneficial in this field.

The need for interventions and corrections in ChatGPT text is expected, according to the teachers, to increase the critical thinking the students, who will be called upon to critically distinguish the important from the unimportant and the right from the wrong. This belief is in line with

Bitzenbauer (

2023) and

Kasneci et al. (

2023), who utilized ChatGPT in physics teaching and observed an enhancement of students’ critical thinking.

On the other hand, as revealed in the interviews, another expected benefit is the improvement of students’ teamwork and the enhancement of classroom dialogue. The above finding of improved teamwork opportunities with ChatGPT is also verified in the literature (

Baidoo-Anu & Owusu Ansah, 2023;

Haleem et al., 2022;

Kasneci et al., 2023;

Rudolph et al., 2023), while research (

Roy & Naidoo, 2021;

Tlili et al., 2023) has highlighted the strong interactive abilities of chatbots themselves when interacting with humans, as the latter are more persuaded and prefer to converse with them over real humans.

Finally, participating teachers reported a reduction in stereotypes and support for students with special educational needs and/or disabilities. Regarding the reduction in stereotypes and prejudice from its use in art classes, there is a contradiction with the concerns in the literature. In particular,

Kasneci et al. (

2023) mention as a disadvantage of ChatGPT the reproduction of stereotypes, as the information from which it compiles its answers comes from a limited database, and in case the texts of this database are biased against a group of people, the same will happen with the given answers of the tool. ChatGPT’s bias against groups can have consequences in education in areas such as student assessment (

Sok & Heng, 2023). Particularly in arts courses, and despite its positive contribution, there is a risk of perpetuating stereotypes through art (

Ali et al., 2023;

Shoufan, 2023). Regarding the support of students with special educational needs and/or disabilities, the literature points to ChatGPT’s main advantage as providing personalized responses (

Baidoo-Anu & Owusu Ansah, 2023;

Elbanna & Armstrong, 2023;

Farrokhnia et al., 2023;

Kasneci et al., 2023;

Rahman & Watanobe, 2023;

Sallam, 2023). Recent research has further highlighted the potential of AI-based tools to support inclusive education and to address the diverse needs of students, including those with specific learning difficulties and disabilities, such us autistic spectrum disorders (

Drossinou Korea & Alexopoulos, 2023a,

2023b,

2024a,

2024b).

However, the main consequence of using ChatGPT in the arts, according to the teachers, is the risk of using ChatGPT for copying and avoiding effort, which is also reflected in surveys by

Iqbal et al. (

2022) and

Waltzer et al. (

2023). According to the teachers, copying would have the direct consequence of inactivating students’ critical thinking skills and reducing their creativity. Also,

Sullivan et al. (

2023) raise the issue of ChatGPT’s lack of artistic originality and creativity. The absence of creativity, the passivation of thinking and its confinement to the ‘ready answer’ solution, and the subsequent shrinkage of writing skills are issues raised by teachers and are in line with the concerns expressed in the literature (

Kasneci et al., 2023;

Pavlik, 2023;

Rahman & Watanobe, 2023;

Zhai, 2022).

Furthermore, the potential risk of misinformation was pointed out by the teachers, as ChatGPT draws from a specific and limited database from which it is asked to provide plausible answers that look as if they were compiled by a human, regardless of whether they correspond to reality—a weakness that is also verified by the literature (

Choi et al., 2023;

Elbanna & Armstrong, 2023;

Mohamed, 2023;

Rahman & Watanobe, 2023;

Tlili et al., 2023). As reported in a similar study by

Mohamed (

2023), concerns were raised about its consequences for critical thinking, the perpetuation of stereotypes, and misinformation. These findings create a new context of challenges in education. It should be noted, of course, that based on purposive sampling, we selected teachers who were already aware of ChatGPT and were able to express an opinion about it.

It is also worth pointing out teachers’ fear about the possibility of being replaced or having their role reduced due to GenAI applications such as ChatGPT, while stressing that the human teacher–student relationship is irreplaceable, especially in art lessons, where a human-centered approach is even more needed. This replacement phobia is also confirmed in the literature by

Elbanna and Armstrong (

2023).

A deeper analysis of these findings through the lens of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) reveals that teachers’ behavioral beliefs function as both enablers and inhibitors of GenAI adoption. Teachers do not merely articulate positive or negative attitudes; rather, they actively negotiate their professional and personal identities in response to technological innovation. Where anticipated benefits, such as enhanced student engagement and inspiration, are perceived as substantial, a readiness to experiment with GenAI emerges. However, even strong positive beliefs may be neutralized in practice by persistent concerns over creativity, authenticity, and the potential erosion of pedagogical values. This suggests that educators are not passive recipients of innovation but rather active agents engaged in an internal negotiation process regarding their professional role. In this way, the TPB does not merely categorize attitudes but helps explain the dynamic tension and ambivalence underlying teachers’ intentions toward behavioral change.

4.2. Expected Support and Facilitators

As it emerged from the teachers’ responses, based on the above possible positive and negative outcomes, they expect to face the acceptance or rejection of students, parents, colleagues, and supervisors—”significant others”—members of the educational community, as well as the possible facilitators and obstacles they think they will encounter. In terms of barriers, a particular reference needs to be made regarding the lack of knowledge about ChatGPT, as highlighted by teachers. It should be noted that of the teachers who volunteered to participate, few were aware of it and were eventually selected. However, even this proportion expressed a lack of awareness of how ChatGPT could be used in art lessons or a lack of confidence in their ability to use it properly and highlighted the need for formal training.

In some cases, they even referred to the ignorance and rejection of others as a discouraging factor and stressed that their attitude towards ChatGPT is determined by personal experimentation and by what they have heard, read, or seen about GenAI. Definitely, as pointed out by the teachers, training is needed, since it is surprising that even they themselves—who, based on purposive sampling, were knowledgeable about ChatGPT and therefore familiar—expressed embarrassment and a request for formal institutional guidance, accompanied by technical support.

The analysis of normative beliefs demonstrates the fluidity and complexity of the social pressures experienced by teachers in relation to GenAI adoption. The data show that teachers can simultaneously perceive enthusiastic acceptance from students and marked hesitation or even resistance from parents and colleagues. Within the TPB framework, this translates into a “hybrid” subjective norm, in which the final behavioral intention is the outcome of a continual negotiation among competing social expectations. This insight extends the interpretive power of the TPB; rather than focusing on a dominant influence, it becomes crucial to examine how teachers weigh and prioritize the various social voices that shape their professional landscape. The process is not static but an ongoing balancing act between personal convictions and the desire for external approval or legitimacy.

Teachers’ control beliefs are not a static acknowledgment of available or missing resources; they represent a dynamic catalyst in the transformation of intention into actual behavior. When teachers perceive that they have sufficient support, training, and infrastructure, their sense of agency translates into a genuine willingness to experiment with and adopt GenAI. In contrast, when uncertainty or institutional barriers prevail, even strong positive attitudes or supportive social norms are insufficient to foster behavioral intention. Interpreted through the TPB, perceived behavioral control does not operate in isolation but systematically interacts with both attitudinal and normative components, either amplifying or constraining their effect. In this context, control emerges as the pivotal moderator that determines whether favorable dispositions or norms are ultimately converted into action.

Taken together, interpreting the findings through the TPB lens highlights that teachers’ intention to adopt GenAI is not simply the result of an additive process of positive and negative influences. Instead, it is a dynamic negotiation field, where each belief component interacts with the others, strong individual convictions may be outweighed by social pressures, while perceived control often acts as the ultimate regulator of decision-making. In this way, the TPB proves valuable not only as a categorization framework but as a tool for understanding the complex psychosocial mechanisms underlying behavioral change in education.

4.3. Implications for Practice and Policy

This research encourages the design of professional development programs focusing on the proper use of ChatGPT in arts teaching. Institutional support through targeted training programs is expected to soften teachers’ resistance and reservations in order to promote the integration of ChatGPT into education. Furthermore, emphasis needs to be placed on the adequacy of technological equipment in schools.

4.4. Limitations of This Study and Suggestions for Future Research

First of all, research limitations can be defined by the research methodology. In particular, qualitative research lends itself to explorations at an initial level, when there are a lot of unknown data and research in the field in question is at an early stage, but it is not suitable for generalized conclusions. In this research case, qualitative research was preferred, as teachers’ beliefs about ChatGPT are relatively unknown in the literature—especially about the arts in particular—but the limitation of qualitative research is noted as the impossibility of drawing general conclusions. Accordingly, the sample size is considered sufficient for a qualitative approach but cannot safely lead to universal generalizations and quantifications. Another limitation regarding the sample is related to the fact that the selected teachers were, based on purposive sampling, aware of ChatGPT, but not all of them had pedagogically used it in the classroom. Finally, a limitation was the absence of sufficient research on teachers’ beliefs about the pedagogical use of ChatGPT in the arts, on which this research could be based.

The research could be extended to larger samples in order to conduct quantitative research to draw conclusions with generalizable validity. It would be interesting to conduct it using a questionnaire versus semi-structured interviews, or even to broaden the sample not only in primary and secondary education but also in higher education, especially among higher education teachers who teach arts courses (for instance, investigating the beliefs of teachers of theatre departments in the country or literature departments). In this way, there could also be comparative relationships about differences in beliefs in higher education. The codes derived by belief category, based on the Theory of Planned Behavior, during this first qualitative approach, can be used as variables in subsequent quantitative studies in order to draw general conclusions.

Furthermore, this study could be extended to investigate the students’, parents’, or principals’ beliefs about ChatGPT and its relation to the arts sector or to identify the research area in a specific educational context or course. Finally, as ChatGPT is continually being updated, there is a need for ongoing review and updating of the research results.

5. Conclusions

The purpose of this study was to investigate teachers’ beliefs regarding the pedagogical use of ChatGPT in arts-related lessons and determine their decision to use ChatGPT for pedagogical purposes. As revealed by the semi-structured interviews, the main positive outcomes that teachers expect focus on enhancing student participation and interest, speeding up the research process, using ChatGPT as a teacher’s assistant, and enhancing teacher and student creativity.

On the other hand, the main negative effects expected by teachers, which impact their attitude towards ChatGPT’s use in the arts, are students using it for copying, reduced critical thinking, misinformation, loss of creativity, reduced interest, substitution of the teacher’s role, and violation of copyright and personal data. Teachers stated that they were not influenced by others’ opinions but expect support from enthusiastic students, advocates of New Technologies and GenAI, those who see ChatGPT as an auxiliary tool, innovators, and the Ministry of Education. Conversely, they expect resistance from those unfamiliar with ChatGPT, skeptical parents, opponents of GenAI, themselves due to fear of conflict with the educational community, and skeptical colleagues.

Facilitating factors include the availability of training and resources, institutional support, personal confidence, and prior positive experiences. Barriers include lack of knowledge and experience with ChatGPT, limited technological access, student resistance, discouragement from the educational community, distrust of GenAI, lack of reliability, difficulty of integration into the curriculum, and concerns about data breaches. According to

Ajzen’s (

1991) Theory of Planned Behavior, these beliefs influence teachers’ decisions regarding the use of ChatGPT in arts classes.