Uncovering the Hidden Curriculum in Health Professions Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Programmatic Norms in Health Professions Programs

1.2. Clinical Identity Development Through Social Learning

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Recruitment and Sampling Methodology

2.2. Participants

2.3. Interview Structure

2.4. Coding Methodology

2.5. Trustworthiness

3. Results

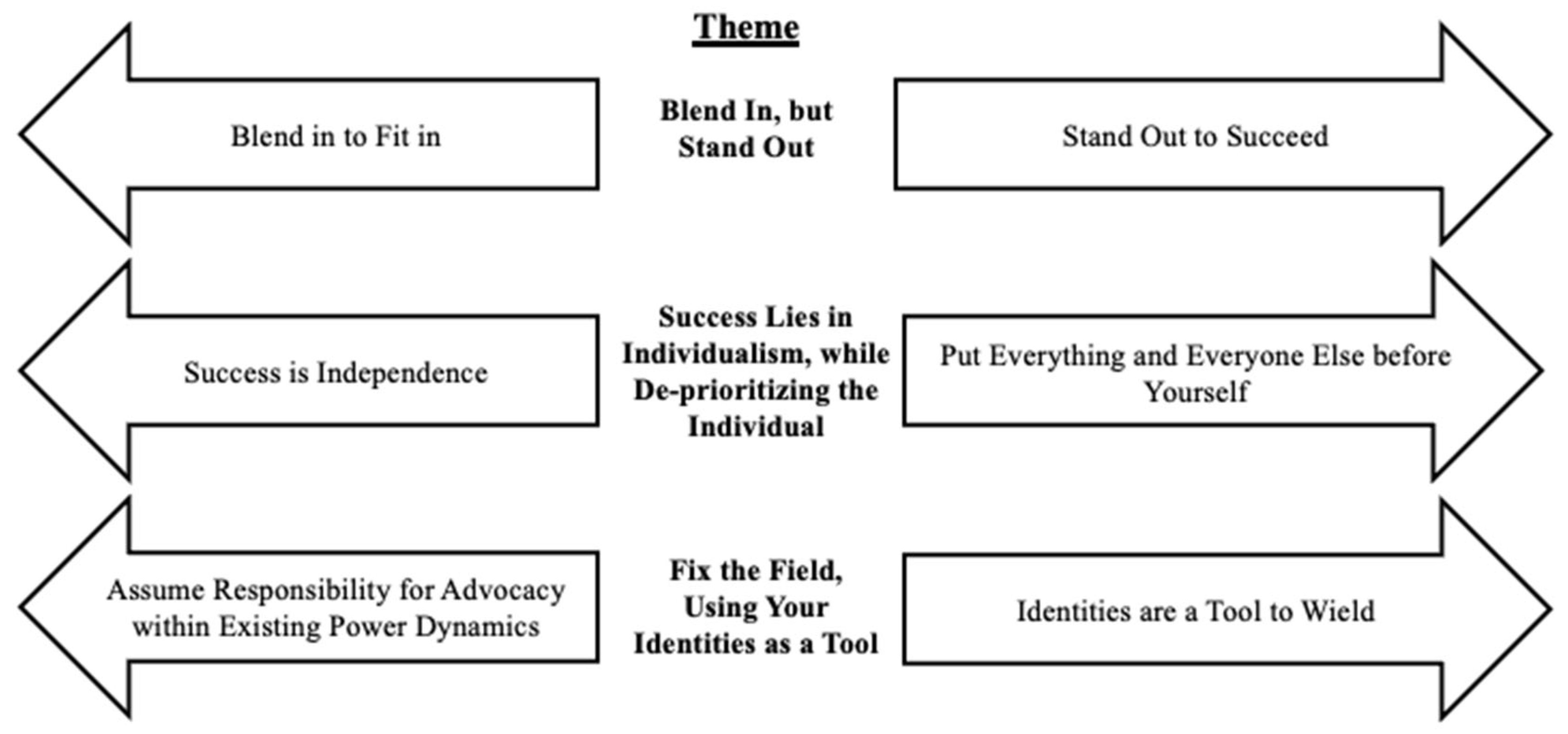

3.1. Theme: Blend In, but Stand Out

3.1.1. Subtheme: Blend In to Fit In

I wasn’t well, the times that I was around [my classmates], because my mindset is different, especially as a person of color. Because, like, I was raised in a different environment to where, like in my life, experiences have made me see things differently… I’m not even having a space at the table. I will either sit in the very front or the very back, and they would talk about the same things. Like about someone’s wedding or traveling and things that. Like it gets old after you talk about it after a certain amount of time. So, then I would take these little breaks because I can get overwhelmed with social interactions at times, especially if we’re all together all the time. And so I would just be on my phone for like a quick second. But everybody was on their phone, and the comment that I got was— She was like one of my supervisors. She said, “Oh that phone! You’re on your phone. And, like you had so many opportunities to engage in a conversation.”

So that makes me feel a lot more isolated. And sometimes they’re like, “oh, you could just use a teacher.” … Sometimes I was like talking to someone— like dating someone— and I’d just use them. But like, I’m not always like talking to someone, and it’s like it sucks. ‘Cause I know someone was like,“Oh, yeah, just like, go on Bumble, find someone.” Just like, why do I have to do this? … This is really making me really regret moving across the country.

3.1.2. Subtheme: Stand Out to Succeed

If you speak up, if you’re active in the community, and if you kind of like make yourself known, you know, like … take initiative early to like, talk to faculty, and … talk about to them about clinical placements that you’re interested in, that that could be rewarded like with the things that you want. Like the internships that you want.

I got [feedback] consistently was that I was really good at kind of communicating with coworkers, and being very professional.

Because there weren’t many like awards or positive things that people, you know, had to compete for… I think that was a key point for me helping to feel like, okay, you know, I can do this. Right? I can belong here, both academically and socially, with friends.

I think it’s just that unwritten rule, you know: being loud and stating your opinion, I have to make sure…as an Asian person who is stereotyped for being like on the quieter side, I have to like break that stereotype-kind-of-thing to do well. But sometimes, you know, I don’t want to have to talk loudly or anything like that. I have to tell myself it’s okay that I don’t want to do that… I’m not like being the stereotype by not following that rule. But it’s hard… I think, in order to do well, you have to follow the rules … [by] not following the rules, like you feel like you’re reinforcing a stereotype, which is, it feels like a weird cycle.

In my program, when I was extremely vocal and self-advocating for myself, it was deemed as me being aggressive, or “she’s doing too much”… But when I went to study abroad and I was quiet, I didn’t talk about all the things I usually talked about. They told me that it’s ruining my professional brand and how I need to really engage more in the culture that I was surrounded in, which is the white culture in my classroom, and I was very confused. Because I’m like, if I talk too much, I’m aggressive or deemed as being too much? But if I’m too quiet, you have a problem with that, too?

3.2. Theme: Success Lies in Individualism, While De-Prioritizing the Individual

3.2.1. Subtheme: Success Is Independence

I think “success” was like being able to do all of work, no problem. Right? Not bugging a lot of the professors… It was just that they were willing to answer questions as long as they weren’t too long, as long as they didn’t require an in-depth answer. And I’m a person who talks aloud a lot to understand things and to like, remember things. … I think, as a student, when you ask for certain like accommodations or like extras, right? You’re asking for more of your professors or faculty’s time, right? And it’s always really up to the faculty whether or not they will give you that extra time. … Asking for that you know, for those accommodations, like for certain professors kind of put me a little bit lower … in certain professors’ eyes.

3.2.2. Subtheme: Put Everything and Everyone Else Before Yourself

I feel like there is an expectation to kind-of drop everything for the program… They’d let you know what like days we have class and what to prepare for two weeks before it. … If you want to hold a job like part time through grad school, just find a flexible job, right? That’s gonna be hard because you don’t know what your class schedule will be like.

I had to get formally diagnosed with ADHD and autism in order to get accommodations for being trans.

They were like, “Oh, well, should you fail clinic now, because you were taken out?” That was a discussion. … I had reached out to my program for support… I tried to do the avenues they tell us to do: reach out to the clinical coordinator. And I felt like they just made me feel like I’m a problem, and you know “too much”. Like actually said that.

But I think that the unwritten rule would be to just be quiet, like to keep your head down a little bit more. I think that you might get further that way unless something really is of great dire issue to your health, or you feel like you’re not going to be able to complete the program unless this happens, like I don’t think some-- Some things are not worth bringing up.

3.3. Theme: Fix the Field, Using Your Identities as a Tool

3.3.1. Subtheme: Assume Responsibility for Advocacy Within Existing Power Dynamics

Excellence in like the faculty … wasn’t expected in the same way when it approached respecting my pronouns or my bodily autonomy

We’re under 40 students… And you tell us that we’re going to be future colleagues… if you say that you respect me for the work that I’ve done at school, and like, you know, you asked me to go to these like events for you. Why can’t you like learn my name? I think that’s a big thing.

I’m super respectful of everyone in the department, but I wouldn’t want anything to come off disrespectful to my peers. And then I’m all about the constructive criticism to everyone. But it’s a very weird position to be in, because like—it’s just not my job [to fix the programmatic culture], and I don’t know how else to say it. And it’s very frustrating, because I feel like, if it’s not my job, whose job is it? Like, how is this program, how’s this field, how— how is anything going to get better if I’m just saying “it’s not my job”? But then I also think, like, all of my peers don’t have to deal with this and… like I have so many things due tomorrow. And why am I spending 2 h thinking about this?

3.3.2. Subtheme: Identities Are a Tool to Wield

[My professor] was talking about how I put ‘Vietnamese fluent’ in my resume, and she’s like … That’s like your selling point, and you should let them know first off, like, “Oh, you’re bilingual, and that’s like a high need.” I feel like that’s like the only time so far [in the program] that I’ve like authentically addressed my like bilingualism and identity … I feel like it should be more like more occurring to be proud of who you are, identity-wise, beyond just race or ethnicity.

It’s important for [PT students] to know how to treat African Americans and people of color, because this is what happened: we touched on it in in this one class. But how would [students know how to] react in these situations? … So let’s interact. Let’s do some interactions and see how you will react because I’m gonna act like how my grandma will act or somebody else’s grandmother. And the moment you disrespect them, you need to know you’re going to have a lawsuit on your hands.

I have to respect [the program’s culture] so it can deem me worthy of being here, so to speak… Okay [I] need to be on my best behavior, and I need to speak just the best way, even if it means, you know, speaking in a different way. … I definitely there was like certain reverence to it.

I can’t be fully myself in grad classes, as well as like in clinical placements. And so it’s hard to find that connection and that sense of belonging when you’re not actually fully being you.

3.4. How Lessons Are Conveyed

4. Discussion

4.1. Alignment with Majority Cultures

4.2. Social Learning of Programmatic Values

4.3. Implications for Clinical Identity Development

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PT | Physical therapy |

| OT | Occupational therapy |

| SLP | Speech-language pathology |

Appendix A

Unannotated Interview Questions

- What does it mean to be a good student in your program?

- What qualities/behaviors/attitudes do you think are most needed to get there?

- What does it mean to be a successful student in your program? You might think of a ‘rising star’ in your department.

- What qualities/behaviors/attitudes are needed to get there?

- How did you learn about these values? How do you know these are the things that are prioritized?

- Let’s imagine that a close friend of yours is about to start the program. You trust them and want the best for them.

- What are the “unwritten rules” that you would let them know about in advance?

- If they wanted to stand out or be a “rising star” in the program, what advice might you give them?

- What is/was your support system or friend group like within the program? What brings you together?

- Professionalism is often discussed and evaluated in programs. Is that something you’ve been evaluated on?

- When you are being evaluated for professionalism in your program, what do you think the faculty and staff are looking for?

- What leads you to believe that? Where did you get that knowledge?

- Do/did you feel a sense of belonging in your graduate program?

- How do you feel that the unwritten rules and expectations we’ve discussed relate to your feelings of belonging in the program? In the field?

- What could your program do to make you feel more like you belonged?

- In what ways have you found yourself changed (either positively or negatively) through your training?

- In summary, what is the take home message for the research team regarding unwritten rules and culture of your program?

Appendix B

Faculty Researcher Positionality Statements

References

- Ahmed, S. K. (2024). The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almairi, S. O. A., Sajid, M. R., Azouz, R., Mohamed, R. R., Almairi, M., & Fadul, T. (2021). Students’ and faculty perspectives toward the role and value of the hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: A qualitative study from Saudi Arabia. Medical Science Educator, 31(2), 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armas-Neira, M., Jaimes-Jiménez, I., Turnbull, B., Vargas-Lara, A., López-Covarrubias, A., Negrete-Meléndez, J., Mimiaga-Morales, M., Oca-Mayagoitia, S. M., & Monroy-Ramírez, L. (2024). Under the covert norm: A qualitative study on the role of residency culture on burnout. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrow, H., & Burns, K. L. (2003). Self-organizing culture: How norms emerge in small groups. In The psychological foundations of culture. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Azmand, S., Ebrahimi, S., Iman, M., & Asemani, O. (2018). Learning professionalism through hidden curriculum: Iranian medical students’ perspective. Journal of Medical Ethics and History of Medicine, 11, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Bandini, J., Mitchell, C., Epstein-Peterson, Z. D., Amobi, A., Cahill, J., Peteet, J., Balboni, T., & Balboni, M. J. (2017). Student and faculty reflections of the hidden curriculum: How does the hidden curriculum shape students’ medical training and professionalization? American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 34(1), 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Behmanesh, D., Jalilian, S., Heydarabadi, A. B., Ahmadi, M., & Khajeali, N. (2025). The impact of hidden curriculum factors on professional adaptability. BMC Medical Education, 25(1), 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L. A., Roter, D. L., Johnson, R. L., Ford, D. E., Steinwachs, D. M., & Powe, N. R. (2003). Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139(11), 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covarrubias, R., Laiduc, G., Quinteros, K., & Arreaga, J. (2023). Lessons on servingness from mentoring program leaders at a Hispanic serving institution. Journal of Leadership, Equity, and Research, 9(2), 75–91. Available online: http://journals.sfu.ca/cvj/index.php/cvj/index (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Cruess, S. R., Cruess, R. L., & Steinert, Y. (2019). Supporting the development of a professional identity: General principles. Medical Teacher, 41(6), 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, B. P., Caston, S., Melvey, D., Maitra, A., Rogozinski, B., & Zajac-Cox, L. (2025). A strategic approach to shift diversity, equity, and inclusion culture in physical therapy education. Advance Online Publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delpit, L. (1995). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom (1st ed.). New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gaufberg, E. H., Batalden, M., Sands, R., & Bell, S. K. (2010). The hidden curriculum: What can we learn from third-year medical student narrative reflections? Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 85(11), 1709–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genoff, M. C., Zaballa, A., Gany, F., Gonzalez, J., Ramirez, J., Jewell, S. T., & Diamond, L. C. (2016). Navigating language barriers: A systematic review of patient navigators’ impact on cancer screening for limited English proficient patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(4), 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guiberson, M., & Vigil, D. (2021). Speech-Language Pathology Graduate Admissions: Implications to Diversify the Workforce. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 42(3), 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M., Forlini, C., & Laneuville, L. (2020). The hidden curriculum in ethics and its relationship to professional identity formation: A qualitative study of two Canadian psychiatry residency programs. Canadian Journal of Bioethics, 3(2), 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafferty, F. W., Gaufberg, E. H., & O’Donnell, J. F. (2015). The role of the hidden curriculum in “On doctoring” courses. AMA Journal of Ethics, 17(2), 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R. X. D., Goodman, N. D., & Goldstone, R. L. (2019). The emergence of social norms and conventions. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(2), 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., & Marconi, V. C. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, E., Bowman, K., Stalmeijer, R., & Hart, J. (2014). You’ve got to know the rules to play the game: How medical students negotiate the hidden curriculum of surgical careers. Medical Education, 48(9), 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, B. D., Ginsburg, S., Cruess, R., Cruess, S., Delport, R., Hafferty, F., Ho, M.-J., Holmboe, E., Holtman, M., Ohbu, S., Rees, C., Ten Cate, O., Tsugawa, Y., Van Mook, W., Wass, V., Wilkinson, T., & Wade, W. (2011). Assessment of professionalism: Recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 conference. Medical Teacher, 33(5), 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, M., Buck, E., Clark, M., Szauter, K., & Trumble, J. (2012). Professional identity formation in medical education: The convergence of multiple domains. HEC Forum, 24(4), 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, J., & Ippolito, K. (2018). A skill to be worked at: Using social learning theory to explore the process of learning from role models in clinical settings. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HRSA Health Workforce. (2024). State of the U.S. health care workforce. National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Available online: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/state-of-the-health-workforce-report-2024.pdf?preview=true&site_id=837 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Hunter, K., & Cook, C. (2018). Role-modelling and the hidden curriculum: New graduate nurses’ professional socialisation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(15–16), 3157–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, K., & Sasada, S. (2022). Development of a new scale for the measurement of interprofessional collaboration among occupational therapists, physical therapists and speech-language therapists. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy, 35(2), 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, A. A. (2016). (No) Harm in asking: Class, Acquired cultural capital, and academic engagement at an elite university. Sociology of Education, 89(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, P. (1968). Life in classrooms. Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M. C., Remache, L. J., Ramirez, G., Covarrubias, R., & Son, J. Y. (2024). Wise interventions at minority-serving institutions: Why cultural capital matters. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetty, A., Jabbarpour, Y., Pollack, J., Huerto, R., Woo, S., & Petterson, S. (2022). Patient-physician racial concordance associated with improved healthcare use and lower healthcare expenditures in minority populations. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 9(1), 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalili, H., Orchard, C., Laschinger, H. K. S., & Farah, R. (2013). An interprofessional socialization framework for developing an interprofessional identity among health professions students. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(6), 448–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox-Kazimierczuk, F. A., Tosolt, B., & Lotz, K. V. (2024). Cultivating a sense of belonging in allied health education: An approach based on mindfulness anti-oppression pedagogy. Health Promotion Practice, 25(4), 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiduc, G., & Covarrubias, R. (2022). Making meaning of the hidden curriculum: Translating wise interventions to usher university change. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 8(2), 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laiduc, G., Slattery, I., & Covarrubias, R. (2024). Disrupting neoliberal diversity discourse with critical race college transition stories. Journal of Social Issues, 80(1), 308–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempp, H., & Seale, C. (2004). The hidden curriculum in undergraduate medical education: Qualitative study of medical students’ perceptions of teaching. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 329(7469), 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugones, M. (1987). Playfulness, “world”-travelling, and loving perception. Hypatia, 2(2), 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, S., Hunt, M., Boruff, J., Zaccagnini, M., & Thomas, A. (2022). Exploring professional identity in rehabilitation professions: A scoping review. Advances in Health Sciences Education, 27(3), 793–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P. K. (2022). Hegemonic whiteness: Expanding and operationalizing the conceptual framework. Sociology Compass, 16(4), e12973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neve, H., & Collett, T. (2018). Empowering students with the hidden curriculum. The Clinical Teacher, 15(6), 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, L. M., & Burks, K. A. (2022, February 1). Creating a racial and ethnic inclusive environment in occupational therapy education. American Occupational Therapy Association. Available online: https://www.aota.org/publications/sis-quarterly/academic-education-sis/aesis-2-22 (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Plummer, L., & Naidoo, K. (2023). Perceptions of interprofessional identity formation in recent doctor of physical therapy graduates: A phenomenological study. Education Sciences, 13(7), 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S., & Beach, M. C. (2020). Impact of physician race on patient decision-making and ratings of physicians: A randomized experiment using video vignettes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(4), 1084–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salhi, R. A., Dupati, A., & Burkhardt, J. C. (2022). Interest in serving the underserved: Role of race, gender, and medical specialty plans. Health Equity, 6(1), 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab-Farrell, S. M., Dugan, S., Sayers, C., & Postman, W. (2024). Speech-language pathologist, physical therapist, and occupational therapist experiences of interprofessional collaborations. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 38(2), 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, D., & Wilkinson, T. J. (2022). Widening how we see the impact of culture on learning, practice and identity development in clinical environments. Medical Education, 56(1), 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M. J., Peterson, E. B., Costas-Muñiz, R., Hernandez, M. H., Jewell, S. T., Matsoukas, K., & Bylund, C. L. (2018). The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(1), 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S. G., Nsiah-Kumi, P. A., Jones, P. R., & Pamies, R. J. (2009). Pipeline programs in the health professions, part 1: Preserving diversity and reducing health disparities. Journal of the National Medical Association, 101(9), 836–840, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshita, J., Wang, S., Loren, A. W., Mitra, N., Shults, J., Shin, D. B., & Sawinski, D. L. (2020). Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Network Open, 3(11), e2024583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torralba, K. D., Jose, D., & Byrne, J. (2020). Psychological safety, the hidden curriculum, and ambiguity in medicine. Clinical Rheumatology, 39(3), 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traylor, A. H., Subramanian, U., Uratsu, C. S., Mangione, C. M., Selby, J. V., & Schmittdiel, J. A. (2010). Patient race/ethnicity and patient-physician race/ethnicity concordance in the management of cardiovascular disease risk factors for patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 33(3), 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Census Bureau. (2024, October 28). Public use microdata sample (PUMS). Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS). Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/microdata.html (accessed on 4 March 2025).

- Valencia, R. R. (2010). Dismantling contemporary deficit thinking: Educational thought and practice. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, G. M. (2014). The new science of wise psychological interventions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K. L., Degener, S., Tondreau, A., Gardiner, W., Hinman, T. B., Dussling, T. M., Stevens, E. Y., & Wilson, N. S. (2024). Nice girls like us: Confronting white liberalism in teacher education and ourselves. Education Sciences, 14(6), 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahyavi, S. T., Hoobehfekr, S., & Tabatabaee, M. (2021). Exploring the hidden curriculum of professionalism and medical ethics in a psychiatry emergency department. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 66, 102885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeheskel, A., & Rawal, S. (2019). Exploring the ‘patient experience’ of individuals with limited English proficiency: A scoping review. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 21(4), 853–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Identity Category | Identities (N, %) |

|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity 1 | White (9, 42.9%) Asian (6, 28.6%), Black/African American (3, 14.3%) Latinx (3, 14.3%) Middle-Eastern (1, 4.8%) Hispanic (2, 9.5%) |

| Gender 1 | Female (17, 81.0%) Male (3, 14.3%) Nonbinary (1, 4.8%) Transgender (3, 14.3%) |

| Sexuality | Straight (4, 19.0%) Queer (3, 14.3%) Gay (1, 4.8%) Lesbian/Sapphic (2, 9.5%) Bisexual (2, 9.5%) Not described (9, 42.9%) |

| Dis/ability 1 | Physical disabilities (5, 23.8%) Neurodivergence (discussed in a disability context) (7, 33.3%) Not disabled (4, 19.0%) Not described (5, 23.8%) |

| Linguistic heritage 1 | Bilingual (4, 19.0%) Language other than English as a first language (3, 14.3%) Not described (14, 66.7%) |

| Immigration | First-generation immigrant (4, 19.0%) Second-generation immigrant (2, 9.5%) Not described (15, 71.4%) |

| Familial college experience | First-generation college student (7, 33.3%) Not described (14, 66.7%) |

| Program location (US region) | Northeast (9, 42.9%) Southeast (5, 23.8%) Midwest (6, 28.6%) West (1, 4.8%) Southwest (1, 4.8%) |

| Code | Definition |

|---|---|

| Blend In to Fit In | |

| Bubbly extroversion | Talk and laugh a lot. Be perceived as friendly and outgoing. |

| Be the “norm” of the profession | Specifically references conforming to the majority demographics in the profession or the program. |

| Blend in to fit in | Be (act, dress, talk) like the majority to be accepted. |

| Find “your people” | Seek others of the same experience to find a support system. |

| “Success” is being liked | Being liked by students, faculty, and/or clients is its own measure of success. |

| Befriend peers | Befriending peers means having a group to work with in class, a social safety net, and colleagues to consult after you graduate. |

| Act neurotypical | Mask neurodivergent traits. |

| Dress professionally by conforming to societal “business” norms | Specific dress code related to business or medical norms (e.g., office attire, scrubs). |

| Speak professionally | There is a specific way of speaking that is “professional” or appropriate (e.g., certain language, dialect, word choice). |

| Be a good listener | Be receptive, and listen to other students, clients, or faculty. |

| Be honest | Be honest. Have integrity. |

| Take others’ perspectives | Learn to understand and appreciate others’ perspectives, even when they differ from your own. |

| Build rapport with clients | Build positive rapport with clients. |

| Be receptive to feedback | Demonstrate that you’re learning from feedback. |

| Stand Out to Succeed | |

| Be loud and confident about trying (even if you fail) | Knowing something means trying and possibly failing—overtly and sometimes loudly. You aren’t trying if you don’t show it externally. |

| Develop personal relationships with professors | Go to office hours, work in professors’ labs, because they have connections and can help you. |

| Demonstrate admiration to faculty and staff | Suck up to faculty and staff to get what you need (e.g., placements, grades, positive regard). |

| Be a leader | Be willing and able to lead others. |

| Speak up in class (non-critically) | Answer questions in class, raise your hand, and participate (but don’t critique). |

| Ask non-critical questions about course material | Ask questions to show you’re engaged (but not critiques). |

| Receive high grades | Grades are an important indicator of your success. |

| Be interested in research | Research is something that faculty care about. Volunteer for a lab, act interested in research. |

| Code | Definition |

|---|---|

| Success is Independence | |

| Be calm and knowledgeable | Be calm and seem like you know what you’re doing. |

| Be proactive, ambitious, high work ethic | Be observed working hard and doing so ahead of time. |

| Be a perfectionist | Be “Type A”, try for high grades, compete against classmates. Possible color-coding of notes. |

| Don’t be a weak link | Prove yourself. Don’t fall behind or be the weakest person in the program. |

| Be over-prepared | Prepare, even if you won’t use it. Always be “on top of it”, even if it’s not discussed as explicitly necessary. |

| Turn work in on time | Turn homework, notes, etc., in on time. Punctuality with assignments is an important indicator of ability. |

| Overcome your disability (for clients and self) | Faculty and students talk about disability as a barrier to be overcome or negative, rather than a part of one’s being. |

| Prioritize learning over grades | Grades don’t matter—just gaining clinical skill. |

| Put Everything and Everyone Else before Yourself | |

| Drop everything for school (have a flexible schedule) | Devote your time fully to school events, group work, special labs, etc. De-prioritize anything that gets in the way. |

| Prioritize school over self or outside life | Don’t let a job, family obligations, commutes, hobbies, etc., get in the way of even small school tasks. |

| Do not bring up individual needs | Do not ask for accommodations, days off for religious holidays, or individualizing of the curriculum or placements. |

| Be on time (physically present) | Don’t skip or be late to class/clinic. Be present and be on time. |

| Be “around” as much as possible | Show up for things, even if they’re not required—for class, volunteer stuff, just generally hanging around the department, etc. |

| Focus and be mentally present | Be focused on class/learning tasks. |

| Do what you’re told without complaint | Do what is asked of you right away, and don’t question, criticize, or complain. |

| Code | Definition |

|---|---|

| Assume Responsibility for Advocacy within Existing Power Dynamics | |

| Advocate for yourself | It’s the student’s responsibility to bring up their concerns. Programs send the message, “we don’t know what you need unless you tell us”. |

| Advocate for clients | Advocate for your client’s needs and/or anticipate them in advance. |

| Advocate in general when no one else can/will | Be a person who will speak up and advocate when no one else will (outside of class or clinical scenarios). |

| Respect and include everyone (e.g., diverse cultures or abilities) | Overt messaging that the program cares about diversity and equity, and students should too. |

| Faculty and staff will actively address concerns | Faculty/staff are able to fix things if you raise a concern. |

| Fix the field | The student is responsible for fixing problems in their field because they hold minoritized identit(ies). The “fix” might be active, or it might be their existence. |

| Walk the fine line of advocacy | There’s a correct amount or way to advocate for yourself/the program. It’s not good if you do more OR less. |

| Do not critique the course material or program | Don’t ask questions or say anything that might be considered critical of the program. |

| Expressing needs/concerns results in punishment | Students experience negative consequences when they tell faculty their concerns. |

| Don’t argue back | Do not resist or disagree with faculty feedback or recommendations. |

| Accept that advocacy might lead to nothing | Programs don’t make the requested changes or act on concerns. |

| Identities are a Tool to Wield | |

| Teach the class/faculty about your identities | Student must teach the class or faculty about aspects of their identities (e.g., repeatedly correct pronoun use, teach the class how to care for Black hair). |

| Be available as a guinea pig or example | Allow faculty/other students to practice skills on you, touch you, or use you as a demonstration (not necessarily related to identity) without complaining/pushing back. |

| Don’t assimilate (resist assimilation) | Be aware of your own values and stick to them (rather than fully adopting the values of the profession). |

| Be happy to be a token representative | Be a token representative of your minoritized identities. |

| Code | Definition |

|---|---|

| Messaging from the faculty, cohort, or leaning environment | |

| Written expectations | Explicitly written down (e.g., syllabus, student handbook). |

| Implicit/explicit messaging from faculty or clinical instructors | Lectures in class, clinic, or individual mentorship, being included in learning environments, etc. |

| How the learning environment is set up | How the learning environment is structured (e.g., labs scheduled last-minute may convey the message to have a flexible schedule). |

| Being rewarded/watching others be rewarded | Norms are learned when people have positive experiences for following them. |

| Being punished/watching others be punished | Norms are learned when people are have negative experiences for not following them. |

| Peer acceptance/ostracization | Peer relationships are contingent on certain behaviors. |

| Watching what others do | Noticing others’ actions and emulating them. |

| Culture of the cohort | Broad social expectations of classmates. May be implicit and created by the students from this cohort or inherited year after year. |

| Participant expectations and prior experience | |

| My culture/how I was raised | Expectations are aligned with the participant’s culture or the lessons they were raised with. |

| Prior experience | Expectations within the program align with other social expectations they’ve experienced (e.g., in the business world, undergrad). |

| I just know | Expectations are just inherent to who they are. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wolford, L.L.; Lugo-Neris, M.J.; Watkins Liu, C.; Nieves, L.E.; Rodriguez, C.L.; Patel, S.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Naidoo, K. Uncovering the Hidden Curriculum in Health Professions Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070791

Wolford LL, Lugo-Neris MJ, Watkins Liu C, Nieves LE, Rodriguez CL, Patel SS, Lee SY, Naidoo K. Uncovering the Hidden Curriculum in Health Professions Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(7):791. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070791

Chicago/Turabian StyleWolford, Laura L., Mirza J. Lugo-Neris, Callie Watkins Liu, Lexi E. Nieves, Christopher L. Rodriguez, Siya S. Patel, Sol Yi Lee, and Keshrie Naidoo. 2025. "Uncovering the Hidden Curriculum in Health Professions Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 7: 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070791

APA StyleWolford, L. L., Lugo-Neris, M. J., Watkins Liu, C., Nieves, L. E., Rodriguez, C. L., Patel, S. S., Lee, S. Y., & Naidoo, K. (2025). Uncovering the Hidden Curriculum in Health Professions Education. Education Sciences, 15(7), 791. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15070791