1. Introduction

Student loan debt has emerged as a defining characteristic of contemporary American higher education, fundamentally altering how students finance their education and begin their adult lives. By 2023, total student loan debt exceeded USD 1.75 trillion nationally, with the average borrower owing approximately USD 38,000 (

Federal Reserve, 2023). This represents a dramatic shift from previous generations, reflecting the combination of rising tuition costs, declining state support for public institutions, and stagnant household incomes (

Goldrick-Rab, 2016). The transformation began in the 1980s when federal policy shifted from grants to loans as the primary vehicle for student aid, coinciding with the expansion of for-profit colleges and reduced state appropriations for public universities. The democratization of college attendance has expanded enrollment among students from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds who often lack family resources to support their education (

Huelsman, 2015), transferring the financial burden from society to individual students and families (

Elliott et al., 2013).

The increasing burden of student loan debt in the United States has raised concerns about its far-reaching consequences beyond individual economic outcomes. Unlike other forms of debt, student loans represent an investment in human capital that disproportionately affects young adults during critical life transition periods (

Houle & Addo, 2019). The burden varies significantly across fields of study, with liberal arts graduates typically facing higher debt-to-income ratios due to lower initial earnings potential compared to professional or STEM fields (

Goyette & Mullen, 2006;

Carnevale et al., 2015). This creates a paradox: those receiving the most civic-oriented education often enter adulthood with the greatest financial constraints. The psychological impact of debt extends beyond mere resource limitation, affecting borrowers’ sense of financial security, autonomy, and life course planning (

Walsemann et al., 2015). Young adults carrying substantial debt may delay homeownership, marriage, and parenthood, which are traditional markers of adult citizenship that historically facilitated community integration and civic participation (

Addo, 2014;

Mezza et al., 2020).

The unique properties of student debt—incurred voluntarily as an investment in future earnings, concentrated among young adults, and varying dramatically by field of study—distinguish it from other financial constraints and suggest distinctive effects on civic behavior (

Houle & Addo, 2019). Research has extensively documented how student debt affects economic milestones such as homeownership (

Mezza et al., 2020), marriage (

Addo, 2014), and career choices (

Rothstein & Rouse, 2011), but less attention has been paid to its potential effects on civic and political participation, which are cornerstone activities in a functioning democracy.

Civic engagement encompasses diverse activities with varying resource requirements, motivational foundations, and institutional contexts (

Zukin et al., 2006;

Colby et al., 2003).

Doolittle and Faul (

2013) provide one of the most widely utilized frameworks for understanding and measuring civic engagement, defining it as comprising two fundamental dimensions: civic attitudes and civic behaviors. Civic attitudes encompass “the personal beliefs and feelings that individuals have about their own involvement in their community and their perceived ability to make a difference in that community,” while civic behaviors are defined as “the actions that one takes to actively attempt to engage and make a difference in his or her community” (

Doolittle & Faul, 2013, p. 4). This two-dimensional conceptualization recognizes the important distinction between internal orientations toward civic life and actual participatory behaviors, acknowledging that attitudes may not always translate directly into action due to situational constraints or resource limitations.

The relationship between economic resources and civic participation has long been central to political science research, with foundational work establishing that socioeconomic status strongly predicts democratic engagement across multiple indicators (

Campbell, 2009). The civic voluntarism model demonstrates that resources (time, money, and civic skills) directly enable political participation (

Verba et al., 1995). This framework emerged from extensive empirical research showing that wealthy, educated citizens participate at dramatically higher rates than their less advantaged counterparts, creating potential inequalities in democratic representation (

Putnam, 2000). From this perspective, student debt might constrain civic engagement by reducing available discretionary resources, forcing graduates to work longer hours, experience financial stress, or delay major life transitions that typically facilitate community involvement.

However, emerging research suggests more complex relationships between student debt and civic behavior than simple resource constraint models would predict. The existing empirical literature shows mixed results, with some studies finding negative associations between debt and engagement (

Velez et al., 2019;

Houle & Addo, 2019) while others document minimal effects or even positive relationships for certain activities (

Despard et al., 2016;

Ojeda, 2016). These contradictory findings likely reflect the multifaceted ways debt interacts with educational background, engagement type, individual circumstances, and broader economic conditions. The inconsistency may also stem from methodological differences in how debt burden is measured, civic engagement is defined, and confounding factors are controlled.

Electoral participation (voting, campaign work) typically requires minimal financial investment but demands political knowledge, efficacy beliefs, and social networks that facilitate mobilization. Non-electoral political activities (contacting officials, protesting, advocacy work) may require greater time commitments, organizational skills, and sometimes financial resources for travel or materials. Community involvement (volunteering, organizational membership, local governance) often demands sustained time investment and may involve membership fees, donations, or opportunity costs from unpaid service (

Zukin et al., 2006). These differential requirements suggest debt might affect engagement types differently, with resource-intensive activities being more vulnerable to economic constraints than lower-cost political activities.

To investigate these complexities, this research examines three central questions that capture the multifaceted relationship between student debt and civic engagement:

How does student loan debt burden affect different dimensions of civic engagement (political participation versus community involvement) among college graduates?

How does the undergraduate field of study, particularly liberal arts education, moderate the relationship between debt burden and civic engagement?

What role do college extracurricular experiences play in developing civic capacities that might buffer against debt’s potential constraining effects?

2. Theoretical Framework

The temporal dimension of civic engagement adds another layer of complexity to understanding how debt might affect participation patterns. Some activities require brief, episodic involvement (voting, attending town halls) while others demand sustained commitment over months or years (serving on nonprofit boards, coaching youth sports, organizing community campaigns). Debt-burdened graduates may gravitate toward episodic engagement that minimizes opportunity costs while avoiding long-term commitments that conflict with career advancement or debt repayment priorities. This shift could alter the character of civic participation, favoring individual acts over collective organizing and short-term advocacy over sustained institution-building.

Multiple theoretical perspectives offer competing predictions about how student debt might influence civic participation, each highlighting different causal mechanisms and boundary conditions. Resource constraint theories, rooted in political economy and rational choice frameworks, suggest that financial burdens reduce available time and money for civic activities, potentially decreasing participation (

McCarthy & Zald, 1977;

Verba et al., 1995). The constraint mechanism operates through multiple pathways: debt service requirements reduce the disposable income available for political contributions or organizational memberships; financial stress creates psychological barriers to engagement by increasing anxiety and reducing cognitive bandwidth for political processing (

Walsemann et al., 2016); and career pressures may limit schedule flexibility necessary for participation in meetings, events, or volunteer activities. Time poverty becomes particularly acute for debt-burdened graduates who may work multiple jobs or longer hours to meet financial obligations.

However, resource constraints operate differentially across engagement types and may interact with other factors to produce non-linear effects (

Brady et al., 1995). Political participation often requires minimal direct financial investment—voting costs only time and transportation, contacting representatives requires primarily communication skills and political knowledge, and many advocacy activities can be conducted online at minimal cost. Community engagement may demand greater resource commitments through volunteer time that competes with paid work, organizational dues or event fees, and social obligations that require disposable income for meals, childcare, or transportation. Geographic mobility, often necessitated by job searches among debt-burdened graduates, can disrupt the local social networks that facilitate community engagement while having less impact on electoral participation.

Contrasting with pure constraint models, relative deprivation theory suggests that economic grievances can motivate political action rather than suppress it.

Gurr (

2011) argues that perceived discrepancies between expectations and reality create frustration that may manifest as political mobilization, particularly when individuals attribute their circumstances to systemic injustices rather than personal failings. Student debtors, particularly those comparing their circumstances to previous generations who faced lower education costs, may experience relative deprivation that motivates engagement focused on systemic reform (

Smith et al., 2012). This grievance-based mobilization may be strongest among college graduates who possess the analytical skills to understand their debt in broader political and economic contexts.

The mobilization effect may be particularly pronounced among moderate debt holders, creating a curvilinear relationship between debt burden and political engagement (

Despard et al., 2016). Low debt levels may be insufficient to trigger grievance formation, as borrowers can manage payments without significant lifestyle constraints. Moderate debt creates an optimal condition where financial burden generates motivation for political action while preserving sufficient resources and psychological capacity for participation. High debt levels may overwhelm coping mechanisms, creating a focus on individual survival that precludes collective action (

Dwyer et al., 2012). This suggests peak political involvement at intermediate debt levels, with different thresholds potentially applying to different demographic groups or economic contexts.

The framing of debt experiences also influences mobilization potential. Graduates who view their debt as a personal investment or temporary sacrifice may be less likely to engage in debt-related political action than those who frame it as evidence of broader systemic inequities. Liberal arts education may be particularly effective at developing critical frameworks that support grievance interpretation, as curricula often examine power structures, inequality, and collective action as responses to social problems (

Colby et al., 2007).

Human capital theory illuminates how educational experiences develop capacities that may buffer against debt’s constraining effects while simultaneously creating motivations for civic engagement. College education cultivates cognitive skills, political knowledge, and communication abilities directly applicable to civic participation (

Becker, 1964). These civic skills constitute a form of capital that may prove resilient to financial constraints, enabling graduates to maintain engagement through efficient participation strategies that maximize impact while minimizing costs (

Mayhew et al., 2016). The civic skills framework emphasizes how educational experiences develop transferable capacities for democratic participation: critical thinking skills enable effective political analysis and issue evaluation; communication abilities facilitate advocacy, persuasion, and deliberation; and organizational experience provides practical knowledge for collective action, coalition-building, and institutional navigation (

Verba et al., 1995).

Educational institutions serve as crucial sites for civic skill development through both formal curricula and informal socialization processes (

Mayhew et al., 2016). Classroom experiences expose students to diverse perspectives, develop analytical frameworks for understanding complex social issues, and practice deliberative skills through discussion and debate. Writing assignments build communication competencies essential for political discourse, while research projects develop information literacy and evidence evaluation skills necessary for informed citizenship. Group projects and presentations cultivate collaboration and public speaking abilities directly applicable to civic contexts.

Social identity theory explains how academic disciplines shape civic orientations that may persist despite economic pressures, creating variation in how graduates respond to debt burdens. Educational fields create distinct professional cultures with varying emphases on civic responsibility, social justice, and democratic participation (

Oakes et al., 1994). These disciplinary identities influence not only career choices but also broader life priorities and value commitments that shape civic behavior. Liberal arts education often explicitly emphasizes civic engagement as a professional and personal responsibility, with students encountering curricula addressing democratic processes, social inequality, and collective action as solutions to social problems (

Colby et al., 2007).

The socialization effects of disciplinary culture extend beyond classroom content to include faculty role modeling, peer networks, and institutional missions that reinforce civic values (

Hillygus, 2005). Liberal arts colleges, in particular, often emphasize service learning, community engagement, and social responsibility as core institutional values that shape student experiences across multiple domains (

Hurtado & DeAngelo, 2012;

Finley, 2011). This exposure may create internalized civic identities that frame engagement as essential rather than discretionary, potentially sustaining participation despite financial pressures. Students learn to view civic participation not merely as a voluntary activity but as a professional obligation and personal commitment tied to their educational identity.

Liberal arts education consistently predicts higher civic engagement across multiple studies, outcome measures, and methodological approaches.

Hillygus (

2005) demonstrated that social science coursework increased political participation even after controlling for selection effects, family background, and pre-college political attitudes. The effects persisted across different forms of participation and remained significant in longitudinal analyses that tracked students over multiple years.

Kim and Sax (

2009) found that humanities and social science majors reported higher rates of political discussion, civic involvement, and community service compared to professional field graduates, with effect sizes that increased over time rather than diminishing after graduation.

Lott (

2013) documented significantly higher civic values among liberal arts graduates, including stronger commitments to social justice, democratic participation, and community service, with effects persisting after controlling for demographic factors, family socioeconomic status, and pre-college orientations.

These patterns reflect several mechanisms through which liberal arts education develops civic capacity that extends beyond simple exposure to political content (

Colby et al., 2007). Curricula often explicitly address democratic processes, political systems, and social institutions, providing knowledge foundations for effective participation. Pedagogical approaches emphasize critical analysis, normative reasoning, and perspective-taking skills that enable graduates to navigate complex political environments and engage constructively across differences (

Mayhew et al., 2016). Classroom discussions expose students to diverse viewpoints while developing deliberative capacities essential for democratic participation, including active listening, respectful disagreement, and collaborative problem-solving (

Colby et al., 2007). Service learning components connect academic content to real-world civic contexts, providing experiential learning opportunities that bridge theory and practice (

Finley, 2011).

Liberal arts graduates face particular economic challenges that may intensify debt’s effects while simultaneously providing resources for civic response. They typically experience slower initial earnings growth and higher debt-to-income ratios compared to professional or STEM graduates (

Carnevale et al., 2015), creating financial pressures that may limit discretionary spending on civic activities or delay life transitions that facilitate community integration. However, they also receive education that provides analytical frameworks for understanding economic issues as systemic rather than individual problems, potentially transforming personal financial stress into motivation for collective political action.

This meaning-making capacity may prove crucial for determining whether debt constrains or mobilizes civic participation. Liberal arts curricula often examine economic inequality, policy analysis, and social movements as responses to structural problems, providing graduates with conceptual tools for understanding their debt experiences in broader political contexts (

Colby et al., 2007). Rather than viewing debt as a personal failing or unavoidable burden, these graduates may frame it as evidence of policy choices that prioritize private over public investment in education, reflecting broader patterns of inequality that require collective responses. This analytical framework may transform debt from a private constraint into a motivator for collective political action, particularly around issues of education policy, economic inequality, and generational justice.

College extracurricular involvement represents a crucial mechanism for developing civic skills that may moderate debt’s effects on post-graduation engagement, providing practical experience in democratic participation that translates directly to post-college civic contexts. Campus activities provide hands-on training in democratic participation through student government, organizational leadership, and collaborative problem-solving (

Sax, 2004). These experiences develop transferable competencies that facilitate later civic involvement regardless of financial circumstances, including meeting facilitation, budget management, coalition building, and conflict resolution (

Bowman et al., 2015).

Student government participation proves particularly impactful for developing civic capacity, providing an experiential understanding of democratic processes that extends far beyond classroom learning. Students learn to navigate complex organizational structures, build coalitions across diverse constituencies, manage budgets and resources, and balance competing interests through deliberative processes (

Verba et al., 1995). These experiences develop leadership skills, political efficacy, and institutional knowledge directly transferable to post-college political contexts. Students also develop professional networks and mentoring relationships that may facilitate later civic involvement by providing information about opportunities, skill development, and social support for continued engagement.

Student publications develop communication and analytical skills essential for political discourse while providing platforms for practicing public engagement on controversial issues. Editors learn to research complex topics, synthesize diverse perspectives, and communicate effectively with varied audiences—competencies directly applicable to policy advocacy, community organizing, and political campaigns (

Bowman, 2011). Staff writers develop interviewing skills, fact-checking abilities, and deadline management that transfer readily to civic contexts requiring information gathering and public communication.

Multicultural organizations cultivate perspective-taking abilities and cross-cultural dialogue capacities increasingly essential for civic participation in diverse communities. Students develop cultural competency, conflict mediation skills, and coalition-building experience across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic lines (

Bowman, 2011). These organizations often address social justice issues directly, providing members with experience in advocacy, protest organization, and policy analysis that creates pathways to continued activism after graduation.

The civic skills acquired through extracurricular involvement may serve as protective factors against debt’s constraining effects, enabling graduates to maintain civic engagement through efficient participation strategies that maximize impact while minimizing resource requirements. Students who develop strong organizational abilities, communication skills, and political efficacy through campus activities may be better positioned to navigate post-graduation financial constraints while sustaining civic involvement (

Bowman et al., 2015). They may also possess larger social networks, greater institutional knowledge, and stronger efficacy beliefs that facilitate continued engagement despite economic pressures.

This study’s theoretical framework synthesizes these perspectives into an integrated model that accounts for both the constraining and mobilizing effects of student debt rather than assuming uniform impacts across all graduates and engagement types. The framework recognizes contingent effects varying by engagement type, debt burden level, educational context, and individual civic capacity (

Houle & Addo, 2019). Five distinct mechanisms are proposed to explain the complex debt-engagement relationship, each operating through different pathways and potentially producing different outcomes depending on individual and contextual factors.

The resource constraint mechanism suggests debt directly reduces available resources for civic participation through multiple pathways: reduced disposable income limits financial contributions to campaigns or organizations; increased work hours to service debt reduce time available for volunteer activities; financial stress creates psychological barriers to engagement; and geographic mobility necessitated by job searches disrupts local social networks that facilitate community involvement (

Brady et al., 1995). This mechanism predicts stronger effects on resource-intensive community engagement than minimal-cost political activities such as voting or online advocacy.

The mobilization mechanism proposes that debt-induced relative deprivation motivates political action, particularly among graduates with analytical frameworks for understanding the systemic causes of their financial burden (

Gurr, 2011;

Smith et al., 2012). This mechanism operates through grievance formation, where debt is interpreted as evidence of broader policy failures requiring a collective response. The effect may be strongest among liberal arts graduates who receive education emphasizing critical analysis of social systems and among moderate debt holders who experience sufficient burden to generate grievance while retaining resources for participation.

The skill moderation mechanism indicates that civic skills developed through college experiences buffer against debt’s constraining effects by enabling efficient participation strategies (

Mayhew et al., 2016). Graduates with strong communication abilities, organizational skills, and political knowledge may maintain civic involvement despite financial constraints by focusing on high-impact, low-cost activities that leverage their competencies. This mechanism predicts stronger protection for graduates with extensive extracurricular involvement and liberal arts education that emphasizes civic skill development.

The identity reinforcement mechanism suggests that disciplinary cultures, particularly in liberal arts fields, create civic orientations that sustain engagement despite financial constraints (

Colby et al., 2007;

Oakes et al., 1994). This mechanism operates through value internalization, where civic participation becomes part of professional and personal identity rather than discretionary activity. Liberal arts graduates may view civic engagement as essential to their role as educated citizens, creating commitment that persists despite economic pressures.

Finally, the threshold effect mechanism describes non-linear relationships where moderate debt enhances engagement through mobilization while extreme debt suppresses it through resource depletion (

Despard et al., 2016;

Dwyer et al., 2012). This mechanism suggests optimal civic participation at intermediate debt levels where financial burden creates sufficient grievance to motivate action without overwhelming coping capacity. The specific thresholds may vary by individual characteristics, local economic conditions, and social support networks.

This integrated framework generates several testable predictions that move beyond simplistic resource constraint models to capture the complex, sometimes paradoxical ways that student debt shapes civic life. The framework recognizes that economic burdens can simultaneously constrain and motivate participation, with effects contingent on educational background, engagement type, relative burden levels, and individual civic capacity (

Schlozman et al., 2018). Understanding these conditional relationships becomes increasingly important as student debt affects larger segments of the population and potentially reshapes patterns of democratic participation among emerging generations of college graduates.

3. Materials and Methods

This study draws upon the College and Beyond II (CBII) dataset, a comprehensive educational research resource that tracks the long-term outcomes of higher education (

Courant et al., 2022). The CBII dataset is particularly valuable for these research questions as it provides detailed information about both student loan debt and post-college life outcomes for a large sample of college graduates.

The dataset encompasses student-level data from 19 public institutions, tracking bachelor’s degree-seeking undergraduates who enrolled between 2000 and 2021 through administrative records. What makes CBII especially suitable for this study is its inclusion of detailed alumni survey data collected more than a decade after graduation. This longitudinal aspect allows examination of how early-career financial constraints, particularly student loan debt, influence major life decisions and milestones in the years following college completion.

The alumni survey captures crucial information about family, economic milestones, employment outcomes, and financial circumstances. The dataset also provides rich contextual information about respondents’ college experiences, including their course content, extracurricular activities, and methods of financing their education. This comprehensive data allows control for various factors that might influence both student loan borrowing and post-college outcomes.

The analysis primarily utilizes the alumni survey component of CBII, which provides detailed information about respondents’ current life circumstances, including their student loan payments, family status, and homeownership situation. The survey’s detailed information on both liberal arts and non-liberal arts graduates makes it particularly appropriate for examining how the field of study might moderate the relationship between student debt and civic participation. The breadth of variables available allows for a nuanced analysis of how financial constraints interact with the educational background to shape civic behavior in the years following college completion.

The final analytical sample consists of 1673 graduates with complete data on all key variables, including 1059 liberal arts graduates (defined as those with majors in arts, humanities, or social sciences) and 614 graduates from professional, STEM, and other fields. For analyses using debt-to-income ratio measures, a slightly smaller sample of 1512 graduates with valid income data was used. The sample reflects diverse backgrounds, with 61.9% White, 12.5% Black, 7.2% Asian, 13.3% Hispanic, and 5.1% other racial/ethnic identities. Women comprise 57.9% of the sample, men 41.2%, and non-binary/other gender identities 0.9%.

The primary dependent variable is civic engagement, measured through three distinct dimensions: total civic engagement, political engagement, and community engagement. The total civic engagement score (M = 6.885, SD = 2.436) combines responses to seven items assessing various forms of civic participation, including voting in the 2020 election, voting in local elections, canvassing, donating to campaigns, protesting, volunteering, and community participation. Political engagement (M = 1.482, SD = 1.696) specifically captures activities related to electoral politics and advocacy, while community engagement (M = 0.799, SD = 0.922) focuses on volunteering and local community involvement.

The primary independent variable in this analysis is the student loan debt burden, measured in multiple ways. First, the study examines students’ self-reported monthly loan payment amounts (LOAN_PAYMENT). Using this information, a categorical variable with four distinct levels was created to capture different degrees of debt burden: no loans (for those reporting USD 0 in monthly payments), low burden (USD 1–200 monthly payments), medium burden (USD 201–500 monthly payments), and high burden (monthly payments exceeding USD 500). This categorization allows the examination of potential threshold effects and non-linear relationships between debt and outcomes of interest.

To account for individuals’ ability to manage their debt payments relative to their income, a continuous measure of debt burden was calculated as the debt-to-income ratio. This measure was constructed using the following formula: Debt-to-Income Ratio = (Monthly Loan Payment × 12) ÷ Annual Income. Specifically, each respondent’s monthly loan payment (LOAN_PAYMENT) was multiplied by 12 to obtain their annual loan payment obligation. This annual loan payment was then divided by their reported annual wages (LABOR_WAGES_AMOUNT) to determine the proportion of annual income devoted to loan payments.

Importantly, this ratio was calculated only for respondents who reported positive income (LABOR_WAGES_AMOUNT > 0) to avoid undefined values that would result from dividing by zero. This approach provides a standardized measure of debt burden that accounts for variation in income levels across the sample. For example, a person with a USD 300 monthly loan payment (USD 3600 annually) who earns USD 30,000 per year would have a debt-to-income ratio of 0.12 (or 12% of their income going to loan payments), while someone with the same loan payment but earning USD 60,000 would have a ratio of 0.06 (or 6% of their income going to loan payments).

For additional analysis, categorical debt-to-income ratio variables were created using two approaches. First, quartiles were used for categorization, creating four groups based on the distribution of debt-to-income ratios in the sample. Second, meaningful categories were created based on commonly used financial guidelines: no debt (debt-to-income ratio = 0), DTI ≤ 5%, DTI 5–10%, DTI 10–15%, and DTI > 15%. An indicator for high debt-to-income ratio was also created, defined as those with ratios above 10%, which is often considered the threshold for financial strain in consumer finance literature.

Control variables include demographic characteristics (race/ethnicity, gender, marital status, parental status), socioeconomic background (parental education, low-income background), educational attainment (advanced degree attainment), college experiences (funding sources, extracurricular involvement, major field), and current circumstances (employment status, leadership positions).

Race/ethnicity was recoded into five categories: White, Black, Asian, Hispanic, and Other. Gender was categorized as Man, Woman, and Non-binary/Other. Liberal arts graduates were identified as those with majors in arts, humanities, or social sciences, comprising 63.3% of the sample.

College experience variables include measures of extracurricular involvement during college, with dummy variables created for participation in various activities, combining both leadership and membership roles. These include: academic clubs/honor societies, multicultural/identity groups, student publications/media, service organizations, performing arts, student government, Greek life, athletics, club sports, and religious groups. Summary measures were also created: total number of activities, total number of leadership positions, and categorical involvement level (no activities, low 1–2, medium 3–4, high 5+). For funding sources, variables were created indicating whether students used various sources “moderately” or “a lot” (values ≥ 3 on the survey scale) to finance their education, including scholarships/grants, student loans, family resources, off-campus work, on-campus work, and personal savings.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models are employed to examine the relationship between student loan burden and civic engagement. The analysis proceeds in multiple stages to address the research questions comprehensively. First, models are estimated for the full sample, examining how student loan burden affects each dimension of civic engagement while controlling for demographic, socioeconomic, and educational factors. The basic specification is:

Second, subgroup analyses focus exclusively on liberal arts graduates to understand how debt burden affects their civic engagement patterns. This approach allows examination of whether the relationship between debt and civic engagement operates differently for this population. Third, interaction effects between liberal arts status and loan burden are tested using the full sample, allowing formal assessment of whether the impact of debt differs by major field. These models include interaction terms between liberal arts status and loan burden categories:

Finally, supplementary analyses using the debt-to-income ratio measure provide additional insight into how relative debt burden affects civic engagement. Heterogeneity by gender and race is also explored to understand potential differential effects across demographic groups. All models employ robust standard errors to account for heteroskedasticity. Statistical significance is assessed at conventional levels (p < 0.10, p < 0.05, p < 0.001).

4. Results

Table 1 and

Table 2 present descriptive statistics for the analytical sample. The sample included 1673 college graduates, with liberal arts majors (arts, humanities, or social sciences) comprising 63% of respondents. As shown in

Table 1, the sample was predominantly White (61.9%), with Black (12.5%), Hispanic (13.3%), Asian (7.2%), and other racial/ethnic identities (5.1%) also represented. Women made up 57.9% of the sample, men 41.2%, and non-binary/other gender identities 0.9%. Most graduates were married (73.0%) and employed (93.5%), with 44.5% having children. Over half (56.2%) had obtained advanced degrees beyond their bachelor’s, and 62.5% came from families where at least one parent had a college degree.

Regarding student loan debt, 47.2% of the sample reported no monthly student loan payments, while 14.5% had low burden (USD 1–200 monthly), 19.1% had medium burden (USD 201–500 monthly), and 19.3% had high burden (exceeding USD 500 monthly).

Table 2 reveals notable patterns across debt burden categories. Graduates with medium and high debt burden reported higher civic engagement scores (7.28 and 7.13, respectively) compared to those with no loans (6.71) or low burden (6.60). This pattern was particularly pronounced for political engagement, with scores increasing steadily from those with no loans (1.48) to those with high burden (2.12).

Educational attainment varied substantially across debt categories, with advanced degree completion rising dramatically from 46% among those with no loans to 80% among those with high debt burden. This suggests that those with higher debt often pursued additional education, which may influence their civic participation patterns. Liberal arts graduates were overrepresented in the low and medium debt categories (69% and 70%, respectively) compared to their overall representation in the sample (63%), while being proportionately represented in the high debt category (59%). Those with medium and high debt burden were less likely to have children (40% and 39%, respectively) compared to those with no loans (49%), potentially reflecting different life course priorities or constraints. These demographic and economic differences across debt burden categories underscore the importance of controlling for these factors in subsequent analyses examining the relationship between debt and civic engagement.

4.1. Full Sample Analysis: Student Loan Burden and Civic Engagement

The results reveal a complex relationship that varies across different dimensions of civic engagement.

Table 3 presents the main regression results examining the relationship between student loan burden and civic engagement for the full sample.

For total civic engagement, the results reveal somewhat paradoxical results. Graduates with medium loan burden (USD 201–500/month) demonstrate significantly higher civic engagement compared to those with no loans (β = 0.344, p < 0.05). However, those with low burden show no significant difference from the debt-free group (β = −0.182, p > 0.10), and those with high burden also show no significant difference (β = 0.125, p > 0.10). This suggests a non-linear relationship between debt burden and overall civic engagement.

The pattern becomes clearer when examining specific dimensions of engagement. For political engagement, both medium burden (β = 0.319, p < 0.05) and high burden (β = 0.183, p < 0.10) are associated with increased participation compared to having no loans. These findings align with the relative deprivation theory’s proposition that financial strain may motivate political action aimed at systemic change.

Notably, community engagement follows a distinctly different pattern. None of the debt burden categories show statistically significant associations with community involvement, though low burden trends toward reduced engagement (β = −0.085, p > 0.10). This bifurcation supports our theoretical framework’s emphasis on differentiating engagement types—suggesting that while debt may mobilize political action, it neither consistently enhances nor constrains local community participation.

Educational and experiential factors emerge as powerful predictors across all models. Advanced degree attainment shows robust positive associations with total engagement (β = 0.540, p < 0.001) and political engagement (β = 0.396, p < 0.001), highlighting how continued education may foster civic skills and networks that translate into participation. Parental education similarly predicts higher engagement (β = 0.269, p < 0.05), suggesting intergenerational transmission of civic values and resources. Notably, having children is associated with lower political engagement (β = −0.489, p < 0.001) but higher community engagement (β = 0.099, p < 0.10).

Extracurricular involvement during college emerges as a strong predictor of later civic engagement. Participation in student government shows the largest effect (total: β = 1.423, p < 0.001; political: β = 1.134, p < 0.001; community: β = 0.254, p < 0.05), followed by student publications (total: β = 0.448, p < 0.05; community: β = 0.181, p < 0.05) and multicultural groups (total: β = 0.408, p < 0.05; political: β = 0.216, p < 0.05). These results support theories about early civic skill development, indicating that diverse extracurricular experiences cultivate lasting civic dispositions.

The strong predictive power of extracurricular experiences, particularly student government participation, suggests that civic skills developed during college create participation patterns that persist despite post-graduation financial constraints. These college experiences may provide both practical skills (organizing, public speaking, deliberation) and civic networks that facilitate continued engagement even under debt burden. The differential effects across activity types, with student government showing the strongest effects, followed by publications and multicultural groups, suggest specific civic capacities may be more transferable to post-college political and community contexts.

Demographic patterns warrant attention. Racial and ethnic disparities persist even after accounting for economic factors, with Asian (β = −0.664, p < 0.05) and Hispanic (β = −0.543, p < 0.05) respondents showing significantly lower total engagement compared to White respondents. These gaps appear particularly pronounced in political engagement, suggesting structural barriers that transcend individual resource constraints.

Major field of study reveals important distinctions. Liberal arts graduates—those in arts, humanities, and social sciences—exhibit significantly higher civic engagement than professional majors. Arts and humanities graduates show the strongest effects (total: β = 0.622, p < 0.05; political: β = 0.679, p < 0.001), followed by social sciences graduates (total: β = 0.419, p < 0.05; political: β = 0.522, p < 0.001). STEM graduates, conversely, show lower community engagement (β = −0.177, p < 0.05), suggesting that disciplinary cultures may shape civic orientations beyond graduation.

4.2. Liberal Arts Graduate Analysis

Table 4 presents results from analyses restricted to liberal arts graduates. The patterns for this subsample show both similarities and important differences from the full sample results (

Figure 1).

Among liberal arts graduates, the relationship between loan burden and civic engagement remains complex but shows some distinct patterns. Medium loan burden continues to be associated with higher total civic engagement (β = 0.390, p < 0.05) and political engagement (β = 0.413, p < 0.05). High burden is also associated with increased political engagement (β = 0.301, p < 0.05), though not total engagement. Notably, low burden is associated with significantly lower community engagement among liberal arts graduates (β = −0.162, p < 0.05).

Several factors emerge as particularly important for liberal arts graduates’ civic engagement. Advanced degree attainment shows even stronger effects than in the full sample (total: β = 0.689, p < 0.001; political: β = 0.462, p < 0.001; community: β = 0.098, p < 0.10). Parental education continues to predict higher engagement, particularly for community involvement (β = 0.120, p < 0.10).

College experiences remain strong predictors, with student government participation showing the largest effects (total: β = 1.473, p < 0.001; political: β = 1.157, p < 0.001; community: β = 0.267, p < 0.05). Student publications involvement also strongly predicts engagement (total: β = 0.484, p < 0.05; community: β = 0.185, p < 0.05).

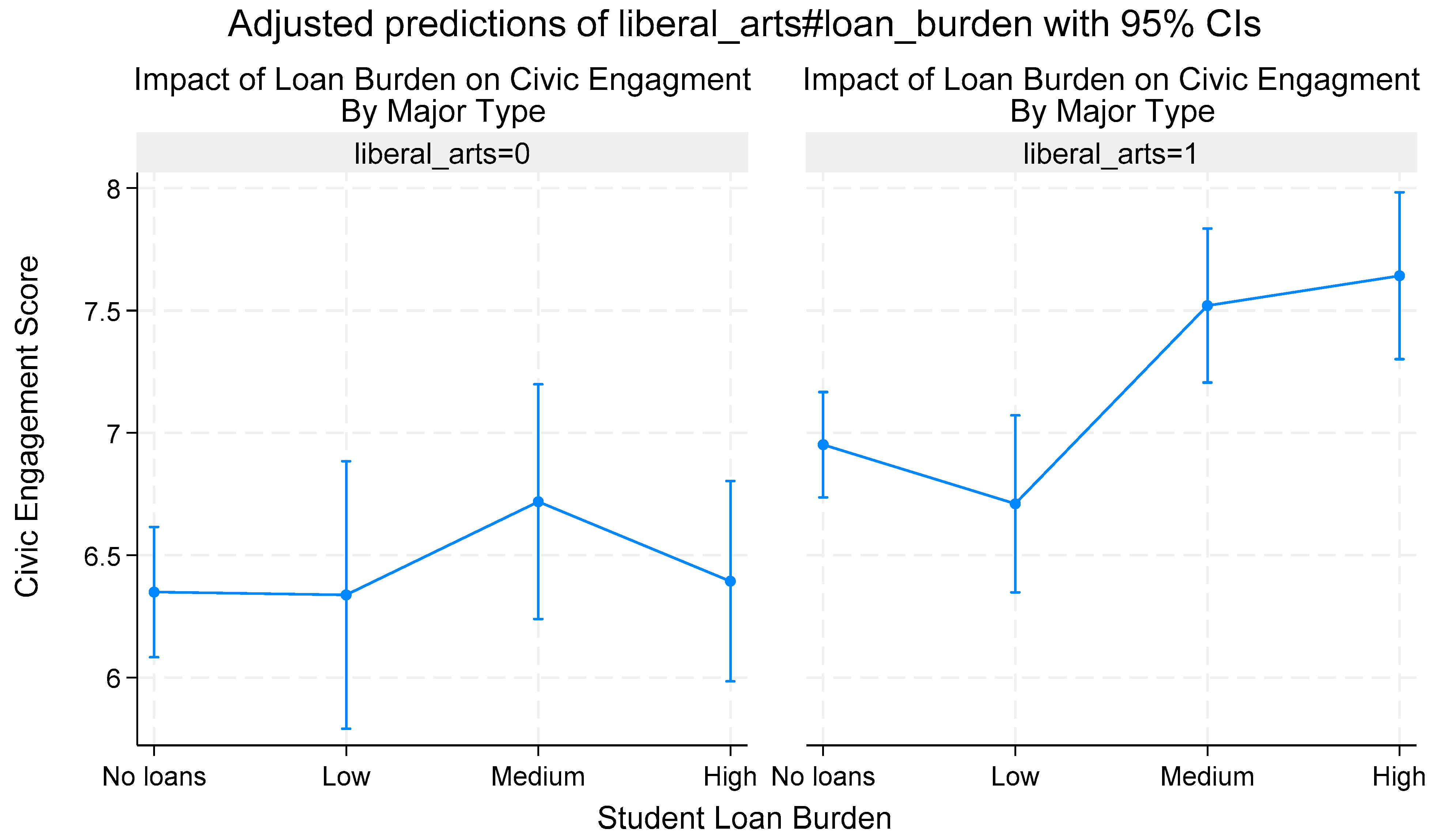

4.3. Interaction Effects: Liberal Arts Status and Loan Burden

Table 5 presents results testing whether the effects of loan burden differ between liberal arts and other graduates. These models include interaction terms between liberal arts status and loan burden categories.

The results reveal significant interactions. Liberal arts graduates show a stronger positive relationship between high loan burden and civic engagement compared to other graduates (interaction: β = 0.646, p < 0.05). The interaction between liberal arts status and high loan burden is positive and significant for total engagement (β = 0.646, p < 0.05), indicating that high debt burden produces stronger civic engagement effects among liberal arts graduates.

Predictive margins analysis clarifies these patterns. For non-liberal arts graduates, civic engagement remains relatively stable across loan burden categories (no loans: 6.35; high burden: 6.39). However, for liberal arts graduates, there is a clear increase in engagement with higher burden (no loans: 6.95; high burden: 7.64). This contrast suggests that liberal arts education may mediate debt’s civic effects, potentially by instilling values or skills that transform financial constraint into civic motivation.

4.4. Debt-to-Income Ratio Analysis

Supplementary analyses using debt-to-income ratios (

Table 6 and

Table 7) provide additional nuance to our understanding of how relative debt burden affects civic engagement. For the full sample (

Table 5), those with DTI ratios of 10–15% show significantly higher total civic engagement (β = 0.522,

p < 0.05) and political engagement (β = 0.469,

p < 0.05) compared to those with no debt. This finding suggests a potential “sweet spot” where relative debt burden is substantial enough to motivate civic action but not so overwhelming as to impede participation.

Among liberal arts graduates specifically (

Table 7), the DTI analysis reveals that those with ratios of 10–15% demonstrate substantially higher total civic engagement (β = 0.972,

p < 0.05) and political engagement (β = 0.601,

p < 0.05). This group also shows higher community engagement (β = 0.223,

p < 0.10).

The interaction models confirm that liberal arts graduates with DTI ratios of 10–15% experience significantly stronger engagement increases compared to their non-liberal arts peers (interaction: β = 1.597, p < 0.05). This reinforces our finding that liberal arts education may fundamentally alter how individuals respond to financial constraints.

4.5. Gender and Race Heterogeneity

Additional analyses examine whether the relationship between loan burden and civic engagement varies by gender among liberal arts graduates. The results suggest some heterogeneity, though most interaction terms do not reach statistical significance. Women with medium burden show somewhat higher civic engagement than men with similar debt levels, though this difference is not statistically significant. Racial/ethnic differences in the debt-engagement relationship are more pronounced. Asian and Hispanic graduates show lower civic engagement across debt levels compared to White graduates, with these gaps persisting even after controlling for debt burden. Black graduates show no significant difference from White graduates once other factors are controlled.

4.6. The Role of Field of Study and Extracurricular Activities in Mediating Debt Effects

The results reveal important patterns in how both field of study and extracurricular experiences shape the relationship between student loan debt and civic engagement. These educational factors emerge not merely as control variables but as significant moderators of how financial constraints translate to democratic participation.

Liberal arts graduates demonstrate distinctive patterns in how debt affects their civic behavior compared to graduates from other fields. While the full sample shows a significant association between medium loan burden and increased civic engagement, this relationship is notably stronger among liberal arts graduates. Similarly, high debt burden is linked to increased political engagement among liberal arts graduates, a relationship not as pronounced in other fields. The interaction models reveal a compelling pattern: liberal arts graduates show a stronger positive relationship between high loan burden and civic engagement compared to other graduates. Predictive margins analysis further clarifies this finding. For non-liberal arts graduates, civic engagement remains relatively stable regardless of loan burden. However, for liberal arts graduates, there is a clear upward trend in engagement as debt burden increases, with those carrying high debt showing substantially higher engagement than their debt-free peers.

This contrast suggests that liberal arts education may fundamentally alter how graduates respond to financial constraints. Rather than debt serving purely as a barrier to participation, liberal arts graduates appear to channel financial pressures into heightened civic action. This transformative effect may reflect how liberal arts curricula often emphasize critical analysis of social systems, potentially providing frameworks for understanding debt as a systemic issue requiring collective action rather than merely a personal burden.

Field of study differences extend beyond debt interactions to baseline civic engagement patterns. Arts and humanities graduates show the highest levels of civic and political engagement, followed by social sciences graduates, with both groups significantly outpacing professional majors. STEM graduates, conversely, show lower community engagement, suggesting that disciplinary cultures may shape not only overall participation levels but also the specific forms of civic activity graduates prioritize.

Extracurricular involvement during college emerges as one of the strongest predictors of later civic engagement, often exceeding the predictive power of debt burden itself. This finding underscores the importance of campus activities as “civic apprenticeships” that develop lasting participation habits. Student government participation shows the most powerful association with later civic involvement, with substantial effects across all engagement forms. This suggests that practical governance experience provides transferable skills directly applicable to post-college civic contexts.

Other extracurricular activities show more targeted effects. Student publications involvement particularly predicts community engagement, potentially reflecting how communication skills facilitate local involvement. Multicultural group participation shows stronger links to political engagement, perhaps indicating how diversity experiences develop capacities for navigating complex social issues. Academic honor societies predict both political and total engagement, suggesting that academic achievement networks may provide pathways to civic involvement. The predictive power of extracurricular experiences persists across debt categories, suggesting these activities develop civic capacities that remain accessible despite financial constraints. Among liberal arts graduates specifically, student government participation shows even stronger effects than in the full sample, suggesting this particular activity may be especially valuable in translating liberal arts education into practical civic engagement despite financial pressures.

These patterns highlight how colleges and universities develop civic capacities through both curricular and extracurricular pathways. The substantial explanatory power of educational experiences—both field of study and campus activities—suggests that higher education institutions play a critical role in developing democratic capacities that prove resilient to financial challenges. Rather than economic factors simply constraining participation in a straightforward way, educational experiences appear to fundamentally shape how graduates interpret and respond to financial pressures, potentially transforming what might otherwise be limiting constraints into motivators for civic action.

5. Discussion

5.1. Key Findings and Their Implications

The relationship between student loan debt and civic engagement defies simple characterization. Rather than a straightforward negative effect, this study finds that moderate levels of debt burden are associated with increased civic engagement, particularly political engagement. This pattern holds for both the full sample and liberal arts graduates, though it is stronger among the latter group.

The positive association between moderate debt and civic engagement may reflect selection effects (those who take on debt may be more ambitious or engaged to begin with) or genuine causal mechanisms (debt may motivate political participation aimed at policy change). The lack of negative effects even at high debt levels challenges assumptions about debt’s constraining effects on civic life.

Liberal arts graduates show distinctive patterns, with stronger positive associations between debt and engagement, particularly at moderate to high debt levels. This may reflect their educational experiences, which often emphasize civic responsibility and political awareness, or their career trajectories, which may provide more flexibility for civic participation despite financial constraints.

Educational factors (both field of study and extracurricular experiences) emerge as powerful moderators of how debt affects civic behavior. These educational experiences appear to develop civic capacities that remain accessible despite financial constraints, and in some cases, may even transform economic pressure into civic motivation.

The findings highlight the importance of considering both absolute debt levels and debt-to-income ratios, as well as recognizing heterogeneity across fields of study, when examining the civic consequences of student loan debt. They suggest that concerns about debt undermining democratic participation may be overstated, at least for certain groups of graduates.

The findings suggest several mechanisms may be at work. First, moderate debt may create a sense of relative deprivation that motivates political action without overwhelming resources needed for participation. Second, liberal arts education may provide frameworks for understanding debt as a systemic issue requiring political engagement. Third, the civic skills developed through college experiences, particularly in student government and publications, appear to translate into lasting participation patterns regardless of debt status. These patterns have important implications for theoretical frameworks linking economic constraints to civic behavior. They suggest that debt’s effects are contingent on educational experiences, relative burden levels, and specific participation types.

5.2. Theoretical Implications and Study Limitations

This study’s findings challenge conventional assumptions about how economic burdens affect civic engagement. Rather than finding a straightforward negative relationship between student loan debt and civic participation, this study uncovers a more nuanced pattern where moderate debt levels are associated with increased engagement, particularly political participation. This pattern is even more pronounced among liberal arts graduates, suggesting that educational context significantly shapes how individuals respond to financial constraints. These results invite a reconsideration of theoretical frameworks linking economic resources to civic behavior, highlighting the importance of considering both resource constraints and psychological motivations for participation.

It is important to note that these findings should not be interpreted as suggesting debt itself is beneficial or that high-tuition, high-debt models of higher education financing are desirable. Rather, the results indicate that under certain educational conditions, graduates can maintain civic engagement despite financial constraints, and in some cases, may channel their economic concerns into political action. Selection effects may also play a role, as students who take on moderate debt may differ in unmeasured ways from those who avoid debt entirely or accumulate high debt burdens. The resilience of civic engagement among those with moderate debt speaks to the importance of educational experiences in developing civic capacities that persist despite financial challenges.

These findings both align with and challenge existing research on debt and civic engagement. Our results are consistent with

Despard et al. (

2016) and

Ojeda (

2016), who documented positive relationships between moderate debt levels and certain civic activities, contradicting simpler resource constraint models. However, our findings diverge from studies by

Velez et al. (

2019) and some aspects of

Houle and Addo’s (

2019) work, which emphasized debt’s constraining effects on democratic participation. This divergence likely reflects methodological differences in how debt burden is measured and civic engagement is conceptualized.

The stronger civic engagement effects among liberal arts graduates align with extensive research demonstrating the civic benefits of liberal arts education (

Hillygus, 2005;

Kim & Sax, 2009;

Lott, 2013). Our findings extend this research by showing that these civic benefits persist and may even be enhanced under financial constraints. This supports

Colby et al.’s (

2007) argument that liberal arts education develops interpretive frameworks that enable graduates to understand personal challenges in systemic terms.

The debt-to-income ratio findings, particularly the “sweet spot” at 10–15% of income, contribute new empirical evidence to theoretical discussions about optimal resource constraint levels. While resource mobilization theory (

McCarthy & Zald, 1977) would predict declining participation with increased financial burden, our curvilinear findings suggest more complex dynamics similar to those proposed by relative deprivation theory (

Gurr, 2011;

Smith et al., 2012).

The differential effects across engagement types support

Zukin et al.’s (

2006) call for disaggregated approaches to civic participation research. Political engagement’s stronger response to debt burden compared to community involvement suggests that economic grievances may channel civic energy toward systemic change rather than local service, consistent with social movement theories about grievance formation and collective action.

The positive association between moderate debt and political engagement aligns with the relative deprivation theory’s proposition that economic strain can motivate rather than deter civic action. Students who take on moderate debt to finance their education may develop a heightened awareness of educational financing policies and economic inequality, translating their personal experiences into political consciousness. This politicization process appears particularly strong among liberal arts graduates, whose educational experiences often emphasize critical analysis of social systems and collective approaches to addressing societal problems. Their heightened response to debt burden suggests that educational context shapes how individuals interpret and respond to economic challenges.

The differential effects across engagement types further illuminate the complex mechanisms at work. Debt shows stronger positive associations with political engagement than community involvement, particularly among those with moderate burdens. This pattern suggests that debt may redistribute civic energy toward forms of participation directly addressing perceived systemic inequalities rather than reducing participation altogether. Political engagement, with its potential for systemic change, may appeal more to those experiencing economic strain than community service activities addressing immediate needs but not underlying structures. This redistribution effect contradicts simpler resource constraint models that predict uniform decreases across engagement types.

The finding that liberal arts graduates show stronger positive associations between debt and engagement—particularly at the 10–15% debt-to-income ratio—suggests that educational experiences fundamentally alter how individuals respond to financial constraints. Liberal arts education may provide critical frameworks for understanding debt as a collective policy issue rather than personal failure, cognitive tools for connecting individual experiences to broader systemic patterns, and civic skills that facilitate effective participation despite resource constraints. These educational benefits appear to transform what might otherwise be a limiting financial burden into a catalyst for democratic participation.

These findings advance the theoretical understanding of civic engagement in several important ways. First, they demonstrate the limitations of purely resource-based models of participation that focus exclusively on constraints without considering motivational factors. While resource constraints certainly matter, they operate alongside psychological processes that can transform economic grievances into civic motivation under certain conditions. Future theoretical frameworks should integrate these constraint and motivation perspectives to better capture the complex dynamics shaping participation.

Second, the results highlight the critical role of education in mediating economic effects on civic behavior. Liberal arts education appears to provide both civic skills that facilitate participation and interpretive frameworks that transform personal economic experiences into political consciousness. This finding supports human capital and social identity perspectives emphasizing how education develops both capacities and orientations that shape civic responses to economic circumstances. Future research should further investigate the specific educational mechanisms—curricular content, pedagogical approaches, and extracurricular experiences—that provide these civic benefits.

Third, the non-linear relationship between debt-to-income ratios and engagement, with optimal effects at moderate burden levels, suggests threshold dynamics that current theoretical models inadequately capture. Low burden levels may be insufficient to trigger motivation while extreme burdens may overwhelm coping capacities. This curvilinear pattern suggests the need for more sophisticated theoretical approaches recognizing how financial pressure operates at different intensity levels. The “sweet spot” pattern implies that both the presence and degree of economic strain matter for understanding civic responses.

Fourth, the differential effects across engagement types suggest the need for more disaggregated theoretical approaches to civic participation. Political and community engagement appear to respond differently to economic constraints, potentially reflecting their distinct resource requirements, motivational foundations, and relationship to economic systems. Future theoretical frameworks should distinguish between these participation forms rather than treating civic engagement as a unitary construct. Particularly important is recognizing how economic strain might redistribute civic energy across engagement types rather than simply reducing participation overall.

These findings also have important implications for higher education policy and practice. While the results should not be interpreted as justifying high student debt levels, they do suggest that maintaining debt within manageable proportions relative to income may be compatible with robust civic engagement. The stronger civic engagement among graduates with moderate debt challenges assumptions that student loan assistance programs must fully eliminate debt to support democratic participation. Rather, policy approaches might focus on ensuring debt remains within manageable levels relative to income—the “sweet spot” (approximately 10–15% of income) that appears optimal for civic engagement. Income-based repayment programs that cap payments at reasonable percentages of discretionary income might be particularly beneficial from a civic perspective, providing financial manageability while preserving resources for civic participation.

The pronounced civic benefits of liberal arts education, particularly under conditions of financial constraint, suggest the importance of preserving access to these educational pathways despite current pressures toward vocationalism. Liberal arts programs appear to develop democratic capacities that remain resilient to financial pressures and may even transform those pressures into civic motivation. Educational leaders should emphasize these civic benefits alongside economic outcomes when articulating the value proposition of liberal arts education. Furthermore, efforts to incorporate elements of liberal arts approaches such as critical thinking, systemic analysis, and normative reasoning into other fields might extend these civic benefits more broadly.

College experiences beyond formal curricula also emerge as important for sustaining civic engagement despite financial constraints. Student government participation shows particularly strong associations with later civic involvement across debt levels. This suggests the importance of protecting extracurricular opportunities despite budget pressures and ensuring they remain accessible to students regardless of financial circumstances. Financial aid programs should consider the total cost of college participation, including time for extracurricular involvement, rather than focusing narrowly on tuition and basic living expenses. Institutional investments in these “civic apprenticeship” opportunities may yield significant democratic benefits even as graduates navigate financial challenges.

While this study advances understanding of how student debt affects civic engagement, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, despite the comprehensive controls employed, selection effects cannot be fully ruled out. Students who choose to take on debt, particularly for liberal arts education, may differ in unobserved characteristics that also predict civic engagement. Future research using quasi-experimental designs, perhaps leveraging policy changes in financial aid, could better isolate causal effects.

Second, the cross-sectional nature of the civic engagement measures limits understanding of how debt affects participation trajectories over time. Future studies employing longitudinal designs could examine whether debt’s effects evolve as graduates progress through repayment, how loan forgiveness programs affect participation, and whether early career constraints have lasting consequences for civic habits. Such designs could better distinguish between temporary redistribution of civic energy and more permanent alterations to participation patterns.

Third, this study relies entirely on self-reported measures of both debt burden and civic engagement, which introduces potential bias in several ways. Respondents may over-report socially desirable behaviors like voting or volunteering while under-reporting financial constraints due to stigma. Social desirability bias may be particularly pronounced for civic engagement measures, as democratic participation is widely viewed as normatively positive. Additionally, recall bias may affect the accuracy of reported civic activities, particularly for behaviors that occurred months before the survey. Self-reported debt amounts may also be subject to measurement error if respondents estimate rather than consult actual records. Future research using administrative records for debt measures and behavioral indicators for civic engagement (such as voter files or organizational membership records) could provide more objective measures of both constructs.

Fourth, while this study distinguishes between political and community engagement, further disaggregation could reveal additional nuances. Future research might examine specific activities like voting, protesting, donating, and volunteering separately to determine whether debt affects different manifestations of civic engagement in distinct ways. This granular approach could further illuminate the mechanisms linking debt to participation.

Finally, qualitative research examining how individuals subjectively experience and interpret their debt in relation to civic participation would complement these quantitative findings. Such approaches could clarify the meaning-making processes through which liberal arts graduates appear to transform financial constraint into civic motivation. Interviews or focus groups could capture the lived experience of navigating civic commitments alongside debt obligations, potentially revealing additional mechanisms not captured in survey data.