1. Introduction

Critical thinking is increasingly recognized as a crucial factor and goal in any educational environment designed with pedagogical characteristics. Its cultivation requires a structured commitment from both teachers and students. in fact, it is a multifaceted and multi-level process that goes beyond simple teaching and involves a dynamic interaction of effective pedagogical strategies aimed at promoting deeper cognitive engagement. The integration of the goal of cultivating critical thinking into curricula requires continuous practice, steadfast commitment, and active participation on the part of students, strengthening their ability to critically analyze, evaluate various sources of information, document, and argue in their field. Findings show that students consider critical thinking essential for their academic and professional development, thus highlighting its importance in promoting their autonomy, independence in thinking, and decision-making (

Papageorgiou, 2023). Furthermore, the cultivation of critical thinking can be supported through repeated exposure to innovative educational contexts. Active participation in these innovative teaching strategies fosters an environment that encourages students to engage deeply in their learning process, further reinforcing the idea that critical thinking is not a static skill, but one that is perfected through continuous effort and engagement (

Kamysheva et al., 2021). Thus, in order to contribute to the cultivation of critical thinking, teachers must commit to a rigorous and consistent approach that incorporates these elements of participation and systematic practice, ultimately enriching the learning experience and promoting a strong educational foundation.

Therefore, educators should deliberately adapt their pedagogical strategies to promote critical thinking through asynchronous and synchronous interactions in e-learning contexts (

Mizal et al., 2021;

Montenegro Rueda et al., 2024). Research shows that, when effectively designed, distance digital learning environments can facilitate cognitive development alongside the acquisition of vital skills that are directly linked to critical thinking, such as student autonomy, metacognitive awareness, and self-directed learning (

Gani & van den Berg, 2024). These skills are critical prerequisites for the successful cultivation of critical thinking, requiring a teaching approach that emphasizes support, constructive feedback, and opportunities for meaningful participation. A deliberate focus on supporting these core elements associated with critical thinking can help dispel any confusion about its scope and significance in the educational landscape.

Distance postgraduate education offers flexibility and access to knowledge regardless of geographical constraints, but the lack of physical presence can limit the direct academic and social interactions that traditionally enhance critical thinking. Students are required to make use of online learning platforms, e-libraries, and collaborative tools, which requires increased skills in evaluating information and developing argumentation. Effective use of these tools requires the ability to critically analyze and evaluate information, skills that are vital for success in higher education (

Hague, 2024). In addition, developing argumentation skills is critical as students engage in online discussions and collaborative projects, where they are required to articulate and defend positions clearly and logically (

Zheng et al., 2023). At the same time, it is crucial that tutors design learning environments that promote critical thinking.

The rapid development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has a significant impact on the learning process in distance learning, both at the level of trainees and instructors. AI facilitates the personalization of learning, offers direct support to students, and simplifies several administrative and teaching processes for instructors (

Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019). AI tools, such as adaptive learning algorithms, data analysis platforms, and automatic assessment systems, offer personalized guidance and feedback to students, facilitating their understanding of complex concepts.

However, over-reliance on AI tools can limit students’ active participation in critical data analysis, reducing the need for analytical and synthetic thinking as well as research processes. over-reliance on AI tools can lead to a decrease in students’ critical thinking and analytical ability, as these tools provide ready-made answers, limiting the need for active thinking. In addition, AI use can lead to decreased attention and concentration, as students may be easily distracted by the constant notifications and features of these tools (

Bozkurt et al., 2024).

In addition, Tutors face new challenges, such as integrating AI into the educational process in ways that do not undermine the development of critical thinking skills and the quality of academic work. Over-reliance on AI tools may limit the development of students’ critical thinking and creativity, as the ready-made outputs provided by AI tools may reduce the need for independent problem-solving and creative exploration (

Habib et al., 2024).

Therefore, the relationship between critical thinking, distance education and artificial intelligence is a complex and multidimensional field of study. This article explores the skill of critical thinking in distance education, with a focus on its development in academic postgraduate environments. First, the theoretical background of critical thinking is analyzed, presenting its basic principles, characteristics, and importance for the cognitive development of learners. Then, the application of critical thinking in the context of distance education is examined, with an emphasis on the challenges and opportunities arising from the use of digital media and learning technologies.

Specifically, this study focuses on the cultivation of critical thinking in two (2) distance learning postgraduate programmes: (a) Education Sciences, specifically in the module EKP65: Open and Distance Education and in the Postgraduate Studies Programme and (b) Education and Technologies in Distance Teaching and Learning Systems—Education Sciences (ETA) in 8 modules. This research was conducted in two distinct phases: Phase A took place in 2016 through face-to-face interviews, while Phase B took place in 2025 through online interviews. Participants included both students and Tutors, allowing the researcher to develop critical thinking skills over about a decade. This study seeks to capture the changes that have occurred in teaching practices, learning experiences and the impact of technological developments, such as AI, on the development of critical thinking in the context of distance postgraduate studies.

1.1. The Concept of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking, as a subject with a deep historical and philosophical tradition, is not only at the center of many scientific and philosophical approaches but also a vital skill for understanding and analyzing the world around us. The term “critical thinking” emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries (

Scriven & Paul, 1996), although the concept of critical thinking is older, with the pre-Socratic philosophers and Socrates playing a central role in the search for truth through argument and the dialectical method. In particular, Socrates’ midwifery method highlights the importance of dialogue and critical analysis for the development of human thought, setting the stage for the ongoing search for what is right and true (

Paul et al., 1997).

Throughout history, critical thinking has been an important foundation of Western philosophy, with the thought of great philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle reinforcing the necessity of systematic thought and analysis (

Al-Ansari, 2006;

Maryuningsih et al., 2019). Systematic thinking, as advocated by these philosophers, allows for the evaluation of ideas and actions to make informed decisions, which makes critical thinking a prerequisite for knowledge and action.

Despite its historical dimension and the widespread recognition of its importance, critical thinking is still an issue, as there is no universally accepted standard definition of the concept. The contemporary literature is filled with a variety of definitions, which often overlap, reflecting the complexity of the concept (

Taimur & Sattar, 2020). The constant search for a clear and effective definition demonstrates the difficulty of categorizing and systematizing this mental process, which varies according to its scope and individual or collective usefulness (

Moore, 2011).

Dewey (

1933), considered the father of critical thinking in modern times, introduces the concept of ‘reflective thinking’, emphasizing the need for conscious and active exploration of beliefs and ideas. The analysis of the reasons that underpin a belief and the consequences to which it leads is fundamental to critical thinking (

Facione, 1989). This approach emphasizes self-awareness and the individual’s ability to question, reflect, and re-examined one’s thoughts and decisions in pursuit of objectivity and reason.

At the same time, the contemporary concept of critical thinking highlights the need for systematic evaluation of information, problem-solving, and developing arguments based on evidence-based data (

Bailin et al., 1999;

Ennis, 2011). In the modern era, the challenges posed by misinformation and information overload make critical thinking even more necessary.

Butler (

2024) points out that critical thinking is essential to avoid the spread of misinformation and to make sound decisions in the modern world.

A review of the literature indicates that while the foundational components of critical thinking, such as analysis, evaluation, and logical reasoning, remain stable, the academic discourse surrounding the concept has evolved in response to shifting educational priorities, technological advancements, and broader sociopolitical contexts. This evolution does not imply that critical thinking itself is a fluid or unstable construct, but rather that different scholars and disciplines have emphasized particular dimensions of it over time. These differences often reflect the contextual demands of each era, such as the need for digital literacy, media discernment, or global citizenship. Simultaneously, at the individual level, critical thinking is understood as a skill that develops progressively through structured practice, reflection, and feedback. In this sense, the literature captures both the plurality of academic perspectives on critical thinking and the recognition that its development is an active, ongoing process within learners.

The evolution is also seen in the actions of the Foundation for Critical Thinking

https://www.criticalthinking.org/ with several seminars, conferences, podcasts, and videos in education, highlighting the need for a continuous and organized approach to the development of this skill, making critical thinking one of the most important skills for modern societies. The emergence of the cultivation of critical thinking in all levels and types of education (formal, non-formal, informal), even in homeschooling, demonstrates the global recognition of the importance of this skill in empowering students to analyze, synthesize, judge, reflect, and create arguments interactively and responsibly.

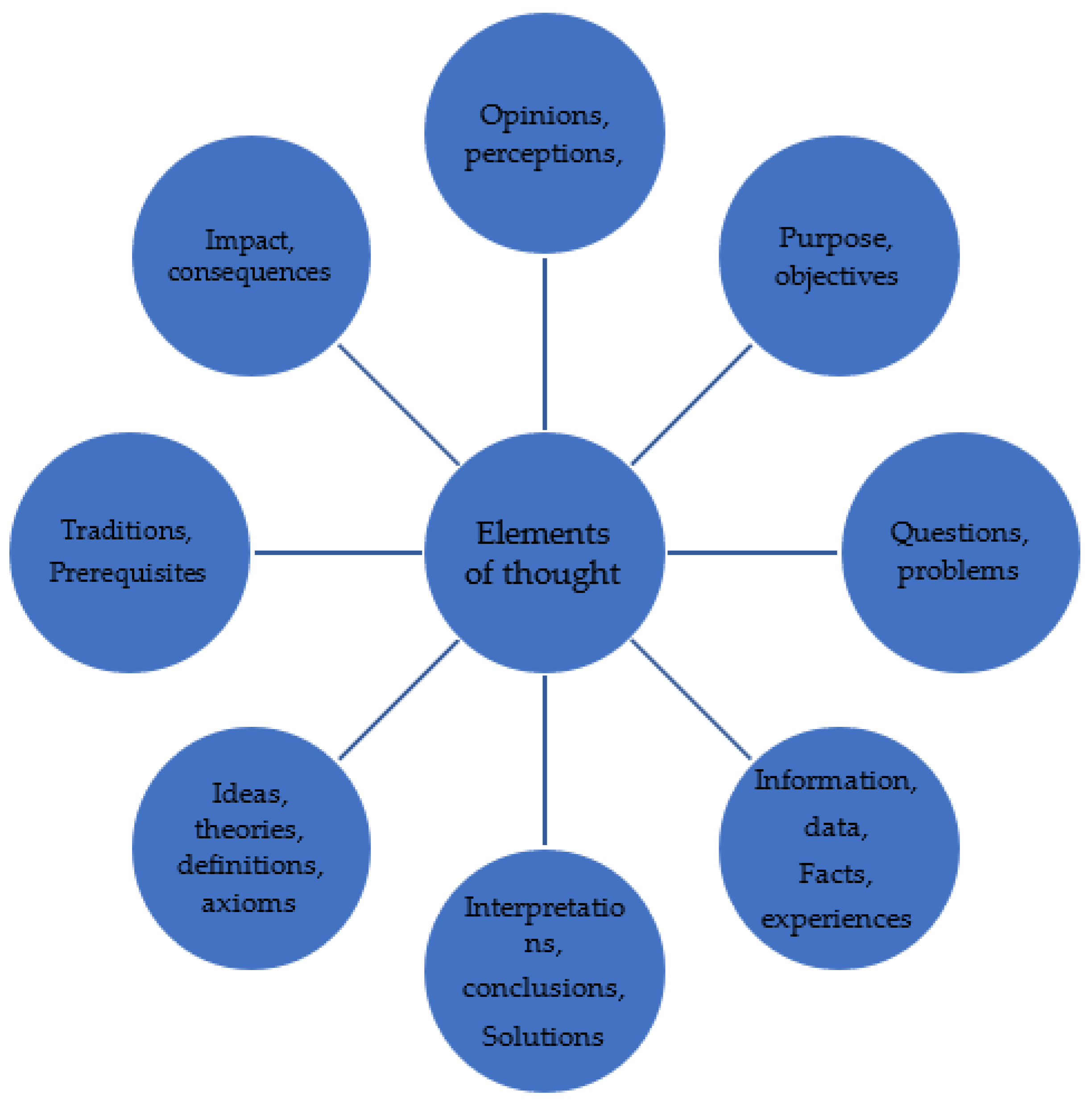

In this context, the

Foundation for Critical Thinking (

2007) presents an extremely interesting online model for learning the Elements and Standards of Critical Thinking. Specifically, eight elements are presented, which are further analyzed in specific questions to understand both the characteristics of critical thinking and, more importantly, to provide a framework for its analysis, understanding and mastery. As stated, to analyze thinking we need to identify and question its structural elements, which are indicatively concerned:

Clarity: Refers to how understandable a message is. Can an example be given? Can it be developed further? Can it be explained?

Accuracy: No mistakes or misunderstandings. Can anyone check that it is so? Are all the necessary facts and details there?

Relevance: How does it relate to the topic of interest? How can it help us with the specific topic?

Depth: Includes the complexity and interconnectedness of relationships. What factors make the problem difficult? What difficulties need to be managed?

Range: Includes multiple angles of view. Can the topic be viewed from another angle in other ways? Are there other points of view?

Logic: Does it make sense when it comes to the synthesis of all the elements and data?

Significance: Focus on the important rather than the unimportant. What is the most important issue and central idea we are dealing with?

Each element of the model (

Figure 1) is analyzed in detail and depth on the organization’s website, and it is of particular interest to study it in detail.

Critical thinking is one of the fundamental pillars of the educational process and personal development. As

Paul (

1995) notes, critical thinking is a “mentally active process” that requires discipline and focuses on the systematic processing of information from observation, experience, reasoning, and communication. According to the same conceptualization, critical thinking is distinguished by clarity, accuracy, consistency, depth, breadth, and fairness, to help to shape beliefs and actions (

Paul et al., 1997).

Chantzouli (

2021) agrees with the view that critical thinking is a continuous and active process, focusing on the individual’s participation in the formation and evaluation of their ideas.

Recognizing the considerable complexity of critical thinking,

McPeck (

1981) and

Brookfield (

1987,

2012) argue that it is a process that requires the cultivation of many skills, such as observation, analysis, and synthesis, which, however, must be combined with the conscious and sustained commitment of the individual. Activating these skills is not limited to their application, but requires a deeper understanding of the process, as

Sternberg et al. (

2007) emphasize, who see critical thinking as a conscious exercise of judgement.

Interestingly,

Flogaiti (

2006) stresses that critical thinking is not synonymous with direct questioning or negativity. Instead, she points to the importance of formulating a logically coherent argument that emerges from data analysis, uninfluenced by preconceptions. Similarly,

Raptis and Rapti (

2007) identify ‘fairness’ and ‘maturity’, i.e., the ability to recognize truth even in opposing views, as defining elements of critical thinking.

The question of the ethical dimension in critical thinking is also very important. According to

Scriven and Paul (

1996), critical thinking without ethical values can become dangerous, since in cases of selfish motivation, its use for personal gain may violate social principles of justice, ethics, and morality. For example, as

Facione (

1989) explains, the use of critical thinking in a legal context can lead to the defence of a guilty person, even if it is morally questionable.

It is important to recognize that critical thinking is not a universal skill that everyone acquires at some point in their lives. A person can continuously develop critical thinking throughout their education or even throughout their entire life. As

Paul et al. (

1997) point out, the quality of critical thinking depends on an individual’s experience and deeper knowledge of a particular domain. Essentially, its development requires lifelong learning, as experience and critical analysis lead to more reliable conclusions and better understanding.

The link between critical thinking and democracy is crucial. As

Glaser (

1941) points out, critical thinking can contribute to the formation of a more democratic society by facilitating discussion and acceptance of other views. In this context, critical thinking becomes a tool for social progress and personal development (

Fisher, 2001).

Overall, critical thinking is a necessary condition for active participation in society, higher education, and the development of democratic values. Despite challenges in educational implementation, the cultivation of critical thinking remains crucial for the formation of conscious, responsible, and ethical citizens (

Guthrie & McCracken, 2010).

1.2. Cultivating Critical Thinking in Distance Learning

The cultivation of critical thinking in distance education has emerged as a crucial factor for the success of learners in the modern digital environment. In such an environment, where learners do not interact face-to-face with their instructors, developing the ability to analyze, evaluate, and make informed decisions is critical to their personal and academic progress (

Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006). The modernization of teaching and learning methods, through the integration of technologies, creates new opportunities for enhancing critical thinking (

Kalyani, 2024), but also new challenges for tutors, who are required to develop strategies that encourage independent thinking in their students.

Distance learning empowers learners’ autonomy and invites them to develop strategies that allow them to interact with the learning material and critically review the information they receive (

Zheng et al., 2023). According to

Garrison (

2017), the development of critical thinking in such environments requires the use of strategies that focus not only on comprehension but also on the active participation of the student to develop the ability to identify, verify, and question different information. In distance education, using technological tools, such as online learning platforms and social media, provides students with opportunities to express their opinions, collaborate, and engage in discussions that enhance their capacity for critical thinking (

Fitriani & Prodjosantoso, 2024).

In recent years, new approaches have been proposed for the cultivation of critical thinking in distance education, such as the development of learning communities and the integration of Open Educational Resources (OERs), which offer students the opportunity to delve into topics and develop reflective skills (

Sanabria-Z et al., 2024). Through these tools, it is important that Tutors create dynamic learning environments that encourage exploration, analytical thinking, and collaboration among students.

It is important to emphasize that developing critical thinking is a complex and demanding process requiring continuous, systematic effort and commitment to effective teaching strategies. The most critical point is to have this perspective and orientation in cultivating critical thinking among teachers and students for the effectiveness of the process (

Matsangouras, 2007). What is required is a coordinated approach that combines effective strategies with regular practice and a commitment to cultivating critical thinking in curricula.

Papageorgiou (

2023) agrees with this approach, emphasizing that implementing critical thinking curricula requires continuous practice and active student participation to enhance their ability to analyze and evaluate information systematically.

The aim of fostering critical thinking skills demands creativity and imagination in all educational activities. This encompasses assignments, self-assessments, exams, and thesis writing, ensuring a constant enhancement of the educational experience across all humanities and distance learning settings.

Kamysheva et al. (

2021) agree with the above reasoning, stating that continuous exposure to innovative environments cultivates critical thinking skills and motivates students to play an active role in their own learning.

This means that tutors, professors, and students must be committed to the process of cultivating critical thinking skills in students. This process is challenging but rewarding and must be systematic and continuous.

1.3. The Role of AI in the Cultivation of Critical Thinking in Contemporary Distance Humanities Studies

AI has a significant impact on distance humanities studies, as it contributes to enhancing critical thinking through personalized learning, data analysis, and adaptive teaching tools (

Wang et al., 2020). According to

Zawacki-Richter et al. (

2019), AI is increasingly used in distance education to support students in evaluating information and developing critical analysis. Intelligent learning systems provide dynamic feedback, facilitating reflective thinking and understanding of complex concepts.

AI can promote critical thinking in humanities studies through advanced algorithms that help in the analysis of historical, philosophical, and literary texts.

Wang et al. (

2020) point out that AI can be used to enhance the exploration of multiple perspectives, encouraging students to compare different approaches and formulate their arguments. In addition,

Long and Magerko (

2020) highlight the need to develop AI literacy so that students evaluate the reliability of algorithms and avoid uncritical acceptance of information.

However, as

Selwyn (

2019) points out, human interaction remains crucial, as critical thinking develops through dialogue and reflection. Although AI provides valuable tools, it cannot fully replace teacher coaching and collaborative learning.

Luckin (

2017) suggests that AI is used as a complementary tool that enhances independent thinking through adaptive assessment technologies (

Wang et al., 2020). Therefore, AI is a valuable tool for developing critical thinking in the humanities, as long as it is used consciously, focusing on human intellect and dialogue.

3. Results

The identification of the characteristics and the process of critical thinking and its multidimensional and multifaceted logical–intellectual–emotional function, which requires the cultivation and combination of many skills for the process of valid and logical conclusions, in which ethics is an important dimension, gives us a basis for proceeding to its study in the context of postgraduate studies, without, of course, implying that it is not required in undergraduate studies.

Focusing, therefore, on the case of postgraduate programmes, we start with the thesis that students “ought to” or should to the maximum extent possible produce knowledge and express their personal opinions with critical thinking on the subject of their study and the relevant literature (Lionarakis, oral discussion, seminar for doctoral candidates, oral presentation, 1/7/2024). The same view is confirmed by the 6 Tutors (2016), supervisors of thesis in the postgraduate programmes “Studies in Education”, as well as by the Tutors of the ETA (2025) where they find both mechanistic reproduction of information, process management, and lack or limited use of critical thinking not only in the thesis but also in all kinds of assignments that students are asked to produce. Critical thinking at the postgraduate level is an extremely important issue and supervisors discuss both the lack of it and the need to cultivate it, without, however, most of the time making it clear and comprehensible to students what they mean and how this can be attributed and reflected in their thesis or assignments.

It is particularly interesting that

Paul and Elder (

2012) in their book “Learning the Art of Critical Thinking”, addressed to students, argue that in any situation, regardless of one’s goals, problems, position, or role, critical thinking is essential to ensure that situations are managed rationally. They point out that we need the best information to make the best choices, and this is achieved through the study of the thought structure itself and the constant review, analysis, and synthesis of data. That is, they suggest the systematic cultivation of a metacognitive process to develop critical thinking. This position complements what Professor

Soccio (

1995; cited in Chatzikyriakou, 2013) had stated in his brief guide to the study of philosophy for young students, in which he defined critical thinking ‘as the conscious, deliberate and rational evaluation of claims according to clearly defined standards of proof’ (

Soccio, 1995, p. 37; cited in Chatzikyriakou, 2013).

The need for the cultivation of this skill is systematically highlighted in the interviews of both the Ts and the students (Ss) who were interviewed in the context of this research. From the processing of the interviews, coding, and thematic analysis of the responses, we conclude the following themes which are related to the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of distance learning:

Lack of critical thinking in the Greek educational system;

Cultivating critical thinking through the creation of Educational Materials;

Written Assignments, Educational Activities, and Dt with characteristics of synthesis, analysis, questioning, self-regulation, evaluation, reflection, and revision;

Importance of literature review and discussion in Written Papers, Dt, and Educational Activities;

Need for in-depth knowledge and study of the subject of the research;

Ability to synthesize positions and make a decision;

Critical evaluation of sources—evaluation of articles;

Difficulty of practical application by students;

The role of AI in the cultivation of critical thinking.

3.1. Lack of Critical Thinking in the Greek Educational System

One of the very interesting findings of the interviews in the context of this research is the common finding of all participants that critical thinking is a difficult process, which is not cultivated in our educational system, despite the references in the curricula and the apparent desire of all those responsible for its development. Critical thinking is subordinated to memorization, examinations, looking for an easy solution, and doing their homework. The views of the participants are typical:

T (2_2016): it’s the Alpha and Omega of everything and what is the most difficult thing to happen, because it’s something that neither our education system nor society has taught people to do.

T (4-2016): critical thinking is supposed to be cultivated throughout education and outside of education. It is a personality trait and, in this case, the higher the grade, the better the outcome. This is a general formulation […] it is the dimension that has occupied experts in these matters for decades now. It is very, very difficult to interpret why it is not cultivated […] I wonder whether the data allow us to claim that curricula, which at the level of operational declarations claim to aim at the experience of criticism, actually improve critical thinking. I am afraid that in some cases, perhaps the reference may be unclear, it may be intentional, we may even have a retreat, a slide backwards in critical thinking.

T (3-2016): it is not cultivated because a basic element of the educational system that determines the whole educational system is the university entrance exams and the inter-school exams. We need to go to higher level skills like critical thinking. But children do not cultivate this in school because the school does not ask them for it.

T (5-2016): I think there is a deficit and I think it’s because of the way the Greek education system is structured. I think that this is because I believe that the Greek system is very much based on the Greek system. In both primary and secondary school, and even in the University, critical thinking is not cultivated through specific scientific ways, so students are basically quoting passages from the literature without engaging in a meaningful dialogue with them. Substantial dialogue means first understanding and then utilizing the literature in what they do.

T (15-2025): Well, I would say a very complex question, because it’s certainly related to the general education of students and I would say that critical thinking should be cultivated throughout the years of education in general education, but unfortunately things don’t seem to be very positive, because we see that critical thinking is not cultivated in education.

This is exactly what T 14-2025 points out:

T_14_2025: In order to see the output of technical intelligence and to be able to exploit and control it, you need to have cultivated critical thinking. For example, you can ask a question and everything it says is untrue or partially true. You have to have criteria to know if it’s valid. You have to know that beforehand. The same for the exam. You ask a question and get an answer and say it’s well written and copy it without checking it.

T (13_2025): clearly for me you can’t develop other skills if you don’t have critical thinking, and if you rank them up, it’s critical thinking. But it is also the most difficult to develop, to cultivate. In school it should be cultivated, because it all starts in school… but school doesn’t cultivate that. Why don’t they want to? Because teachers don’t know how to cultivate critical thinking in children either. So this process does not go very far, because nobody knows much. All the years the books write everywhere about critical thinking but nothing is done… We don’t know how to do it in school. Now in graduate school, we have 4 assignments where we put the activities and so on, we give a stimulus to cultivate critical thinking. But students are process oriented regardless of the AI.

The problems in the cultivation of critical thinking are also emphasized by ST (3-2016) stating that it is not required in most studies and thus the students rest or do the minimum they can due to increased obligations. In particular it is pointed out:

S (3-2016): I think it has to do with the current context and especially here in Greece with what we’ve been living in the last few years. I don’t think that the policy that exists right now in education is aimed at producing critically thinking citizens. They are tools of a globalising society. That is the point and the policies that are being drawn up are in that direction. The skills required of children in schools are technocratic skills, not critical thinking skills.

S (2-2016): they have perhaps rested in their previous studies in reproducing something ready-made. They are not asked and so they have not practiced in this part, in giving their own point of view to combine, analyze and synthesize previous theories whatever their studies. I too, since my early studies, in very few courses we were asked to synthesize information. It was mostly memorization and presentation. It was not cultivated. On the other hand even if asked, some are content to just get a postgraduate degree with a low grade, which can be obtained without critical thinking.

3.2. Cultivating Critical Thinking Through the Creation of Educational Materials

Instructional materials are an extremely important component of distance education (

Giosos et al., 2009;

Keegan, 2001;

Lionarakis, 2001;

Manousou, 2008). It is considered the heart of the distance learning process and its creation and quality are critical. The educational material must contribute to the interaction of students with the content, creating dialogue and the possibility of immersion to better understand what they have to study. In this context, the educational material creates the learning environment for the cultivation of critical thinking. Its role in the two (2) Postgraduate Programmes of HOU, ES and ETA is twofold; on the one hand, students are exposed to distance learning materials that emphasize the cultivation of critical thinking during their studies, and on the other hand, they learn to create educational materials themselves in which the aim is to cultivate critical thinking. Both the T and several students point to the role of distance learning materials in the development of critical thinking.

The T (3-2016) states: “The Educational Materials studied by students through the activities and case studies provide an opportunity for students to search, analyze and synthesize their views about the content”.

The T (9-2025) points out the same. t is very interesting the reflections that the students get into through the Educational Material. They have to answer judgmental questions or do something that contributes to the cultivation of their critical thinking”.

S (5-2016) notes: One point that was interesting for me in the material even if I didn’t do the activities is that I was getting into a reflection. I had to think and many times, I guess I was always looking for feedback to see if I thought it through.

S (12-2025) also develops a similar concern: When I was called upon in module ETA52, which is about creating the educational material, to create educational material, I realized how difficult and how demanding it is to provide opportunities for your trainees to cultivate their critical thinking. I had to find very different activities for this. At this point I even used AI tools for help and the truth is that they were helpful. But you had to know what you wanted and ask the right questions.

3.3. Written Assignments, Educational Activities, and Dissertation with Characteristics of Synthesis, Analysis, Questioning, Self-Regulation, Evaluation, Reflection, and Revision

More specifically, regarding the cultivation of critical thinking in the context of postgraduate studies, all the Ts and students point out the need for the existence and cultivation of critical thinking, trying to define it very specifically. Characteristically, the T (4-2016) states:

“Critical thinking should characterize the Dissertation and every Educational Activity, such as Written Assignments, etc.… It is too difficult to answer the question of how easy it is to cultivate it. But it is a very important question”.

On the same issue the T (3-2016) notes that:

“The purpose of the design of the HOU’s Med courses and all the elements they include such as the Written Assignments, the Dissertation is to cultivate critical thinking. The topics we set require the student, not to reproduce the material they read, but to critically position themselves in relation to it. One of the goals of the program, and therefore of the topics, is to cultivate critical thinking. Now, to what extent this is implemented is to be assessed […]”. Whether this has remained at the level of rhetoric and how it is implemented I cannot say”.

The importance of critical thinking is also stressed by ST (7-2016):

“Above all critical thinking, it’s the key characteristic, the first one I consider for me. From there on, he must … have the ability to … be able to … beyond critical thinking … be able to … have the ability to explore the field and of course after critical thinking to be able to discern what he has found”.

The elements of self-regulation and self-control highlighted by ST (9-2025) are also excellent and interesting:

“Critical thinking self-regulates, self-coordinates. It places you in the surrounding space of the diplomatic research and you operate accordingly towards the topics. Without critical thinking you can’t do anything. You need it everywhere. In the formulation of the topic, in how you work on your thesis, in not straying from the topic, in what you need to find and what you need. On the internet there is infinite data, AI gives huge new possibilities but you must know how to choose, to know what you want. If an adult wants to do a Paper or even more so a Dissertation and has no critical thinking in what they do, they will either get off track or never finish it”.

We find that dealing with data management, focusing on the specific objectives of the assignment and the choice of material are issues that students are confronted with and, in order to cope, they use their critical thinking to a greater or lesser extent and cultivate it further. Of course, in addition to critical thinking on the issues of proper use of data, the students must also use and properly apply their knowledge and skills in research methodology, academic discourse and academic ethics.

3.4. Importance of Literature Review and Discussion in Written Papers, Dissertations, and Educational Activities

Both the Ts and the students point out that the main points, in which critical thinking is highlighted, are the literature review and the discussion during the preparation of an academic work in all the Educational Activities, Written Works, and Dissertations. Specifically, a T states:

T (4-2016): the search, identification and isolation of the most critical sources of relevant literature. The careful synthesis of the thesis problematic. The inventiveness of the methodological choices. The documentation of the choices and the highlighting of those points that seem to be dark spots in the documentation. The synthesis of the results is the most serious issue.

They look for the literature to cite opinions on the issues they deal with, and cite them. This process in Phase A of an academic paper is unavoidable, but as the process progresses, they must move to a more sophisticated stage, which involves a real dialogue of sources, discussing them with each other, comparing them, and going deeper into them.

All the Tutors (both in 2016 and 2025) find that the areas where students’ critical thinking is highlighted are the quality of the documentation.

The T who participated in the first research as a T in the MSc in Education Sciences and in the second one as a T in the postgraduate RTD in the field of the creation of distance learning material, finds that: “the creation of educational material contributes a lot to the cultivation of critical thinking as students through the process of creation are invited not only to be creative but to use their critical thinking”.

An important highlight and one that seems to differentiate the process is the introduction of AI. In 2025, Tutors point out that with AI tools, literature review can be performed much faster. The issue is that students need to cultivate their critical thinking. The tools make their work easier, but they need to do more rigorous and careful checking.

3.5. Need for In-Depth Knowledge and Study of the Subject of the Research

A further element highlighted by the subjects of the present research is the link between critical thinking and the deep knowledge, study, and evaluation of a subject.

Typically, the T (1-2016) states:

“There can be no critical thinking without knowing an issue deeply. No one has critical thinking about something they don’t know”.

The same is also pointed out by T (2_2016):

“Critical thinking means that I acquire those data, so that I have the criteria to evaluate whatever is in front of me. This, in our field, means a lot of study, a very good knowledge of the subject and boldness for someone who already has the knowledge […]. For me, it has to do with theses that deal with theoretical issues and therefore get into deeper waters. When you have to work on a theoretical issue, it means that you have to have a critical attitude towards things from the outset. In those that have empirical research, this is largely seen in the review of the literature and in the interpretation of the data and results”.

We find that in each case the Tutors point out the good knowledge of the subject, the study of it with a critical eye and especially in the context of the literature review, which gives all the necessary data for the interpretation and deeper knowledge of the subject. In other words, it is pointed out that one cannot remain solely on one’s own personal-experiential perception but must discover and examine all the dimensions through the study of the literature.

The T (11_25) in the same issue states:

“It is necessary to study … to study the subject. You have to know if the student, anyone, does not know the subject can understand the dimensions of the subject in order to cultivate critical thinking. If you don’t know the subject you will speak too superficially. We find this too often and from the questions students ask they do not go into depthA. In-depth knowledge of the subject contributes to the research process.

This view remains strong from the Ts in 2025 as they all talk about the need for deep thinking and understanding of the issues students study, but this is less and less evident.

The students did not refer to the same issue, i.e., the need for deep knowledge of the subject, but pointed out the need for good and in-depth processing of sources, and qualitative research.

S (3_2016) mentions: In Dissertation, I realized that I had to go deeper into the subject. You can’t work on the surface, you won’t get a good result. You need to study it well.

Characteristically, ST (10_2025) says: “Critical thinking is to see, based on the information and material at hand, which ones agree with each other, in which cases one theory contradicts or complements the other. It is choosing from these theories which one is the most appropriate for the particular research, in a particular context and circumstance. To be able to draw a new conclusion of his own. Sure it is important in the beginning but I think much more so in the conclusion part. In the conclusions and the discussion of the results, so that’s where you have to have a critical discussion of both the results against each other and the results against the theoretical framework. Of course all this seen from a new position and view of the time. Also in modern times you have to pay attention to the results that AI gives you. You save time but it needs attention…”.

3.6. Ability to Synthesize Positions and Make a Decision

One of the major problems that we often see in the IC, and not only of course, is the simple listing of positions without composition. Synthesis is an important skill but it is akin to critical thinking, as it requires an in-depth study of views, finding common and different elements to proceed to their dialectic and critical examination. This is precisely what all the Ts point out. More specifically, we mention the following positions, on which all participants agree.

The report of the T (4_2016) is characteristic:

Once the student has managed to select the sources, he or she should be able to process them further, to use them and synthesize them. Synthesis could be said to be is a great step or an excellent training in critical thinking.

Also interesting is the following point:

T (9-2025): ‘When he knows how to present the position, the contrast, he knows how to do the composition. In the field we are moving in, which is the social sciences and humanities, and not an equation or an experiment, you are dealing with concepts that have been approached from many different angles and have been formulated in many different ways and with many different contents. The person who has the ability to present the views and through them to arrive at the synthesis obviously has that skill.

T (8-2025) adds:

Critical thinking is an evolutionary process, it seeks sources, it is important to evolve the process to see it over time, with evolutionary processes. In relation to AI we can’t control it, we need to take it seriously and include it in our design to support students to cultivate their critical thinking.

S (2-2016) states that the ability to synthesize information: “…is to be able to analyze and at the same time synthesize the information found. Reason. The way in which he writes this information must be short, concise, and to the point. Then he must be able to organize all of this both in his mind or his clipboard and in his work. The way of presentation, that is”.

S (10-2025) adds that the ability to compose is an essential skill for selection for quality postgraduate studies: “I identified the need for critical thinking in the very first Learning Activity of the ETA MSc when I was asked to select sources and evaluate them. Seemingly it was something simple however it turned out to be very complex and demanding as it needed searching with criteria, selection, documentation and in the end synthesis. I personally found it difficult”.

It is obvious from the above views how important is the synthesis of information and the ability to present this synthesis by going beyond the simple quotation of information, but also how difficult and stressful this seems for the students.

3.7. Critical Evaluation of Sources—Evaluation of Articles

A prerequisite for the critical treatment of the literature review is the critical evaluation of the sources. Who writes or says an opinion and where? For example, is it a post on a personal blog or a peer-reviewed journal article?

This processing of information linked to the skill of selecting and evaluating sources is an important component of critical thinking, particularly for postgraduate students.

According to the T (1_2016), a student “should learn a way to assess and evaluate things even if it is a coded way. This is not in-depth judgment, but it is a simple form of critical faculty because the more you look, engage and evaluate, the more you go deeper and can move to greater stages. At this stage, of course, you definitely need to learn a model of evaluation, even if it is a simple one: Which journal is it in? What does it say? How good is it methodologically?”.

T (8-2025) points out, “Critical thinking is the ability the student must have to determine for himself what it means to study a book or article critically. How can I judge whether it is scholarly, important, and proven in some sense through research? How can I compare articles and literature that address the same topic? How can I through this comparison choose what I need for my research? Most importantly, how can I structure arguments using the literature for my own research and work? There is in my opinion the greatest difficulty for students in being able to structure arguments”.

S (1-2016): ‘It seems mostly starting at first, to lay the whole thing out. Because you have the possibility now with the internet, depending on the topic, you can run into two parameters or you can have a lot of sources or you can have not a lot of sources and in both cases you need critical thinking to be able to evaluate and substantiate…”.

S (9-2025): ‘A skill is to be able to search for valid sources, in scientific journals and in conferences, which have gone through a crisis, but today you have to know how to use applications of AI.

We find from the views of all the Ts that the critical evaluation of sources is the first important step in critical thinking, as it leads to credible argument building and substantiation. This process certainly requires systematic work and familiarity, discussion, and constant review, and certainly requires and contributes to critical thinking.

3.8. Difficulty of Practical Application by Students

There is another serious issue raised by students concerning the acceptance of critical thinking. They appreciate that on the one hand they are not ready to accept a point of view different from their own, but also that they often lack objective criteria for marking. Very typically S (4-2016) states:

“For example, in the subjects we had, when we were asked for our opinion and we told the tutor that we were thinking of writing this, we asked him for his opinion if what we were reporting was correct and we saw that he was negative, then what critical thinking is there in the end? I won’t forget in one of my own assignments where I wrote the same thing and a fellow student wrote the same thing, I got a 6.5 and my fellow student got a 10 […]. I think it is the expression of personal opinions and cannot be graded. That’s what’s wrong with it. I cannot grade an experience of yours and an experience of mine. It is wrong to rate that”.

Clearly, we have almost all been confronted with similar testimonies from students or may even have some personal experience. Certainly there are such incidents, in which it becomes apparent that the T finds it difficult or cannot easily accept a viewpoint different from his own, for reasons related to his own personality, maturity, position, etc., but we need to go a little deeper and lead students to reflect on whether there are dimensions of the issue that they have not explored. On the other hand, regarding the view that one cannot grade an experience mentioned by S (4), on the one hand, the QAs are not exclusively about experiences or mere recording of them, but data collection based on scientific methodology, and on the other hand, grading and evaluation is about documentation about the experience-data and not about the experience itself. After all, it is particularly interesting to transform an experience into scientific data and to document the viewpoint because it means producing new knowledge, which is the goal. In no way do we want to discredit or devalue an opinion, it is certainly accepted with the greatest respect and gives us an additional stimulus for reflection, however, we want to put a question mark on the way it was communicated-presented and documented.

The dangers for critical thinking are highlighted by both Ts in 2025 and students; pointing to the use of tools as ready-made solutions without deepening and personal elaboration as negative processes that undermine both critical thinking and thinking.

T (15_2025) … Now the other angle that seems to reinforce more pessimistic scenarios and concerns the risks, hence, the negative effects of an improper use of AI. Several people talk about necrosis of creative thinking, reduction of imagination and perhaps the most important risk may be that it will “grow” ignorance and learning difficulties since the user will find ready-made solutions and will cease to think. This is a danger not only for critical thinking but for human thinking.

S (9-2025): It can look like an AI tool can look like an easy answer and give you an answer, you can copy it and go through the lesson, and then what? Is it your grade? Did you learn something? Did you look it up? No benefit, instead you are fooling yourself.

The discussion on the cultivation of critical thinking may highlight its importance, but both the T and the students point out that the application of critical thinking has many difficulties. It takes a lot of effort and practice. Students recognize its importance but when they are asked to apply what they have learned theoretically they find it difficult. Very typically F (2-2016) states that to be able to apply what I learned I realized that I have to study and process every piece of information. Specifically, ST (2-2016) points out:

I think that in order to put into practice what I have learned theoretically I have to research and look for new dimensions. It is not easy…. When one does not start with ready answers and is actually looking to find out whether something will happen or not and to what extent it will happen—if it is quantitative—being open to any new information and at the same time having in mind what is already happening or what others have said about it, all this can be done at the same time. To synthesize the information and not be ready to validate himself. To see what arises with an open mind. It’s demanding.

S (14-2025) confirms the difficulty by stating: In all of this you need the help and support of the T, particularly through feedback. I wait every time to see what the T will write to see what went wrong what else I should do. T kept talking about the critical approach to the literature review but it took me a long time to understand what he meant. The truth is that I wanted to finish the assignments. To cultivate critical thinking you have to constantly reflect. I think we students struggle with this. We don’t reflect at every stage. In my opinion, it should be done at every stage. What did I have? Where have I got to? Relative to my timeline, how far have I progressed?

S (12-2025) says whenever I use an AI tool I’m happy to save time but I’m worried if I’ve learned something and what I’m missing. Whenever I am in a hurry I do it quickly but very often I go back to see if I did it right. Of course I expect this from the T. However, it is very important and at the same time difficult. I will stress that it seems to me that the support of the T is never enough if there is not the real personal involvement and willingness to research, search and reflect.

The same points are made by the Tutors. They find it difficult to put into practice what is asked of them in the context of distance learning.

The T (9-2025) states: Many times we Ts discuss among ourselves that students do not bother to study the pronunciation carefully. You see that they ask you questions that are answered in the pronunciation but they see them. Many times we answer the same point over and over again as they easily ask a question without looking at the questions again. I really want to emphasize that 80% of the questions I get are on issues that if they re-read the pronunciation they would find them.

The same point is made by T (15-2025): especially in this era of AI, it is important that students should be constantly suspicious, and want to “tire” their minds a bit to be real thinking people. Not to accept and take advantage of everything that AI “serves” them. We will constantly point out that the most critical skill is critical thinking.

3.9. The Role of AI in the Cultivation of Critical Thinking

AI tools, according to all the Phase B Ts, can contribute a lot to the cultivation of critical thinking as they can quickly find sources, but they have to check very carefully if they are reliable and if they answer the questions they ask. It is very crucial that they also ask the right questions.

T (11_2025): Yes, of course yes. I think the students who are thus more serious and who are more interested, try to look at it critically and intervene. That is, they are looking for something that can give them some initial impetus, but then they try to tailor it to make it fit their needs to use it as they want. Of course there are others who take it completely uncritically and just quote it. I see them as being half and half, but without saying for sure, I can’t say for sure. It’s more evidence than proof and especially the last six months.

T (15-2025): lately we all see that artificial intelligence offers tools that help people to analyze data, evaluate information and make better decisions, so it offers possibilities but also risks for individuals. Therefore, the issue of AI should be seen from two different perspectives, at least as it appears from the first results observed by users. What are these two perspectives? One is that it opens up horizons in knowledge. The user can actually find himself in new fields to search for other knowledge, it is a great opportunity really, something that in previous times would have cost him time, effort, and pain in the sense of effort, whereas now he is just inside new horizons. The conditions created with new data enhance critical thinking since AI allows the user to be able to analyze huge data sets and get relevant information quickly. At the same time, personalized learning is encouraged because educational platforms tailor learning to the user’s needs, enhancing logical thinking and creative problem solving. This allows users to examine multiple sources and form informed opinions, exercising their judgment, as long, of course, as long as it is used carefully and in conjunction with human analysis and judgment…

I think a very wise tutor specialized in artificial intelligence said in an interview that ultimately the issue is not how artificial intelligence will help us but how we will ask the right questions and the quality of the result that will be obtained from the use of artificial intelligence will depend on that.

S (8_2025): tools more that help in detecting articles and evaluating articles … that’s how I would see it more to save time and go deeper. I think if I did it now it would be a very different graduate school.

4. Discussion

This study offers an in-depth exploration of how critical thinking is cultivated, or hindered, within Greek postgraduate distance education, drawing on interviews with both students and tutors across two significant timeframes (2016 and 2025). The analysis of the data reveals persistent systemic limitations alongside emerging opportunities, particularly through the integration of intentionally designed digital pedagogies and the nuanced use of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Despite the national curriculum’s rhetorical emphasis on critical thinking, the findings highlight a significant gap between policy and practice. Participants repeatedly emphasized that the prevailing pedagogical culture in Greek education, especially at the primary and secondary levels, continues to prioritize memorization and high-stakes examination performance over inquiry-based learning, interpretive engagement, or dialogic exploration. This traditional approach fosters what

Spector (

2019) refers to as mechanistic thinking, whereby learners are conditioned to accept and reproduce information rather than interrogate, critique, or reframe it. Consequently, students often reach postgraduate education with underdeveloped habits of independent reasoning and limited exposure to epistemological pluralism.

This issue persists even within higher education. Both student and tutor accounts reveal a pattern of surface-level engagement with academic material, where academic success is often associated with accurate reproduction of existing knowledge rather than creative synthesis or argumentation. Such findings resonate with the critiques of

Freire (

1996) and

Brookfield (

2012), who argue that critical thinking emerges not through passive reception but through dialogic processes that challenge students to make meaning collaboratively and critically. These findings also reinforce the observation that critical thinking is not an incidental outcome of educational participation but requires a deliberate, embedded pedagogical commitment.

Nevertheless, this study points to encouraging developments within the context of the Hellenic Open University (HOU). Participants described how the structure of distance learning, when designed effectively, can create fertile conditions for the development of critical thinking. Asynchronous discussion forums, scenario-based learning, and reflective tasks enable students to engage with content at their own pace and depth, supporting cognitive autonomy and metacognitive awareness. These findings align with the Community of Inquiry framework proposed by

Garrison et al. (

2001), which positions cognitive presence, teaching presence, and social presence as interrelated elements that sustain higher-order thinking within digital learning environments.

Moreover, the asynchronous and decentralized nature of distance learning appears to encourage greater responsibility and self-regulation among learners. This supports

Zimmerman’s (

2002) model of self-regulated learning, which highlights the role of goal-setting, strategic action, and self-reflection in academic development. Participants described how tasks such as digital thesis writing, peer feedback exchanges, and thematic forums prompted deeper engagement with content and fostered a sense of epistemic agency. This suggests that digital education, when carefully designed and scaffolded, has the potential to move beyond transmission models and support dialogic and inquiry-based learning, as advocated by

Laurillard (

2012).

Another central theme that emerged from the data was the transformative potential of source evaluation in promoting critical thinking (

Mezirow, 2007). Students who were encouraged to critically analyze, compare, and synthesize academic sources appeared to develop not only stronger arguments but also more nuanced epistemological beliefs resulting in personal growth through a transformative process of development (

Mezirow, 2007). This aligns with the work of

Facione (

1989),

Kember and Ginns (

2012), and

Paul and Elder (

2012), who emphasize that systematic source evaluation fosters analytical reasoning, evidentiary rigor, and academic integrity (

Carr & Kemmis, 1997). However, the findings also indicate that without structured guidance and feedback, source evaluation may become a superficial exercise. As

Brookfield (

2012) observes, criticality is not innate; learners require modelling, dialogical exchange, and iterative practice to distinguish credible sources from unreliable ones and to integrate diverse perspectives meaningfully into their arguments.

The role of Artificial Intelligence in this evolving landscape emerged as both promising and problematic. While participants recognized the value of AI tools in enhancing efficiency, expanding access to information, and supporting preliminary drafting or language refinement, concerns were raised about cognitive offloading and the erosion of critical engagement. Some students appeared to rely uncritically on AI-generated content, bypassing the reflective and analytical processes essential to the development of independent thinking. This concern resonates with

Gerlich’s (

2025) critique of overreliance on generative AI, which can inadvertently deskill learners and undermine epistemic responsibility. Nevertheless, when students were taught to critically interrogate AI outputs by comparing them with peer-reviewed sources, identifying underlying assumptions, and reflecting on their accuracy, AI became a productive scaffolding tool rather than a cognitive shortcut (

Lim et al., 2023).

These findings point to an urgent need for the cultivation of AI literacy, not merely as a technical competency but as a critical epistemic skill. As

Bozkurt et al. (

2024) argue, educators must now reimagine their roles as facilitators of discernment and ethical engagement in digitally mediated environments. In this context, the role of the educator becomes not only to transmit knowledge or evaluate outcomes but to curate spaces of inquiry, co-construction, and reflective judgement.

Overall, the findings suggest that the development of critical thinking in distance postgraduate education requires a recalibration of pedagogical priorities. Educators must move beyond content delivery and actively design learning experiences that promote reflection, interpretation, and synthesis. Rather than treating critical thinking as an abstract goal or assumed outcome, it must be embedded explicitly in the curriculum through the integration of dialogic activities, iterative assignments, and explicit criteria that reward analytical depth. Furthermore, learning environments must cultivate psychological safety and intellectual curiosity, enabling students to explore and revise their thinking through meaningful interaction with peers, tutors, and diverse sources of information, including AI.

In conclusion, this study sheds light on both the enduring obstacles and emerging affordances in cultivating critical thinking within Greek postgraduate distance education. While the legacy of exam-driven, teacher-centered schooling continues to impede the development of independent thinking, the structural features of well-designed digital learning environments offer valuable opportunities for transformation. The careful integration of source evaluation, the critical use of AI, and the intentional design of dialogic pedagogies are not optional enhancements, but essential strategies for fostering reflective, responsible, and critically engaged learners in the digital age. As educational systems navigate a rapidly changing technological and epistemic landscape, the cultivation of critical thinking must remain a central and consciously pursued objective.

5. Conclusions

The present study offers valuable insights into the cultivation of critical thinking within postgraduate distance education programmes, despite certain limitations, such as a limited participant pool and a specific focus on a singular educational context. This research, which is a decade-long inquiry aimed at contributing to the scholarly discourse surrounding critical thinking, elucidates both the challenges and opportunities that arise within online learning environments for both students and tutors. Participants’ experiences and perceptions are examined in this study, which reveals the distinct characteristics that define critical thinking in digital contexts while suggesting targeted strategies for enhancement.

This study’s key finding highlights the critical role that critical thinking plays in distance learning. This is because both groups of participants—students and tutors—recognize it as a key skill for navigating today’s complex and information-rich digital environment. This research reveals a number of challenges faced by both groups in developing this skill, highlighting an important gap in current pedagogical practices that requires urgent attention. Specifically, many participants expressed concerns about cultivating critical thinking in all forms of education, whether face-to-face or distance learning. The cultivation of critical thinking should be the primary goal. Participants emphasized that critical thinking is not a simple skill, but involves a range of interrelated abilities, such as analysis, evaluation, synthesis, and interpretation. These skills can be developed by students, who must be given the initiative, as well as being taught in ways that promote reflection, critical thinking, and teamwork when analyzing information. It is important to note that genetic artificial intelligence offers opportunities and challenges in this context. While artificial intelligence technologies can enrich personalized learning experiences and provide diverse resources, there is a risk that students may become overly dependent on these tools, which could hinder their genuine engagement.

Significant improvements in analytical skills are achieved by students who proactively manage their learning environment, have access to diverse sources of information, and actively participate in academic dialogue. These findings highlight the urgent need to create supportive learning environments that promote student autonomy and engagement, thereby fostering the critical thinking skills necessary for academic success and meaningful participation in an ever-changing world.

Furthermore, this study delves into the concept of critical thinking, emphasizing that it is not a simple skill but rather a complex set of abilities that include analysis, evaluation, interpretation, and synthesis. It is defined as a purposeful and conscious process requiring sustained effort to scrutinize information and discern biases. The findings emphasize that students who can independently manage their learning, access a variety of information sources, and actively engage in academic discussions significantly improve their analytical skills.

Finally, we can say that if we want to encourage critical thinking in distance education, it is very important for teachers to create courses that get students involved in a step-by-step way by talking and working together. When used in the right way, AI can help to provide personalized learning experiences. However, it is important to be cautious and not to become too dependent on these technologies in a way that undermines the ability to think critically. It is a shared responsibility of students, educators, and educational institutions to promote critical thinking.

The following definition of critical thinking is proposed by us, based on this study: “Critical thinking is a complex, self-regulated cognitive process involving the analysis, evaluation, interpretation, and synthesis of information from various sources to draw informed conclusions and navigate the modern digital learning environment safely. It requires active participation, the ability to assess the reliability of data, and the capacity to utilise information and technology effectively”.